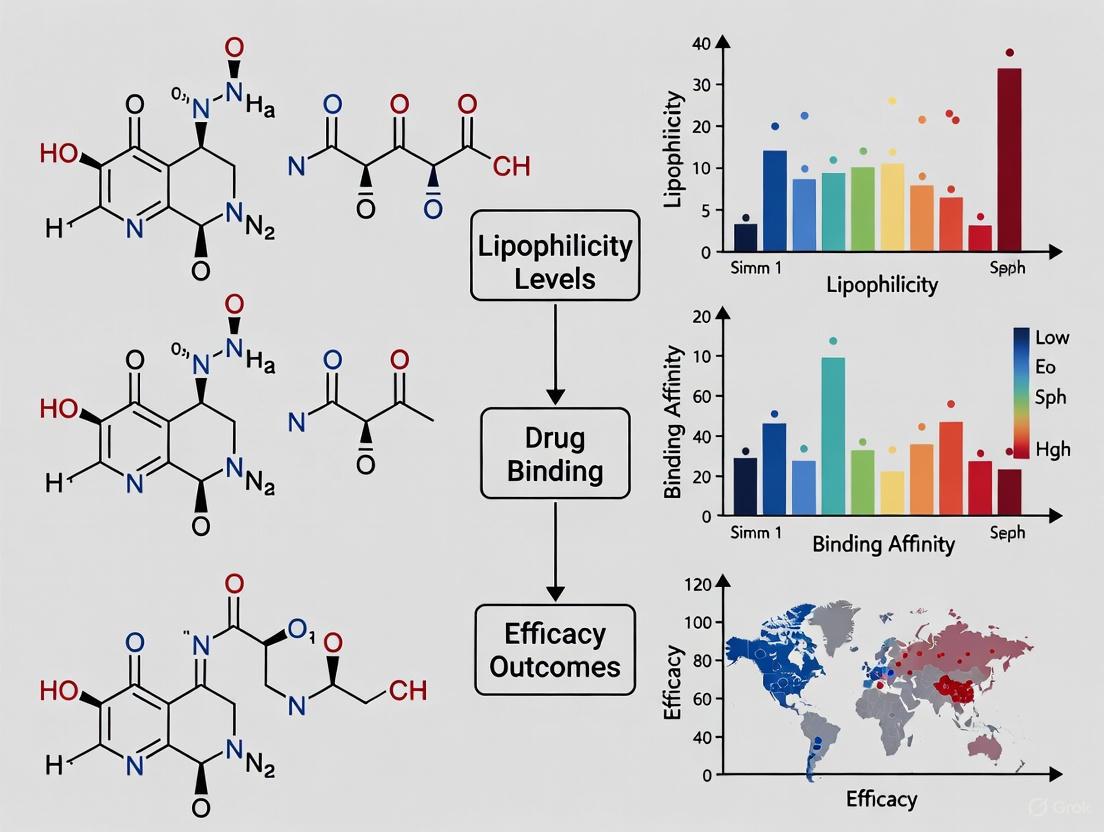

Balancing Lipophilicity in Drug Candidates: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimizing ADMET Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of lipophilicity in modern drug discovery and development.

Balancing Lipophilicity in Drug Candidates: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimizing ADMET Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of lipophilicity in modern drug discovery and development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores fundamental concepts of drug lipophilicity and its profound impact on absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET). The content covers established and emerging methodologies for measuring and predicting lipophilicity, practical strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls like poor solubility and excessive plasma protein binding, and advanced validation techniques for comparing molecular efficiency. By synthesizing foundational principles with contemporary computational and experimental approaches, this resource serves as an essential guide for optimizing drug candidates to achieve the delicate balance between permeability and solubility required for clinical success.

Lipophilicity Fundamentals: Understanding the Core Principles and Its Critical Role in Drug Disposition

Core Definitions: Log P and Log D

What is the fundamental difference between Log P and Log D?

Log P (Partition Coefficient) is the logarithm of the ratio of the concentration of a compound in its neutral (unionized) form between a non-polar solvent (typically n-octanol) and water. It is a constant for a given compound under specific temperature conditions [1] [2] [3]. Log D (Distribution Coefficient) is the logarithm of the ratio of the concentration of all forms of a compound (unionized, ionized, and partially ionized) present at a specific pH between n-octanol and water [1] [2] [4]. Log D is therefore pH-dependent and provides a more accurate picture of a compound's lipophilicity under physiologically relevant conditions.

The following table summarizes the key differences:

| Feature | Partition Coefficient (Log P) | Distribution Coefficient (Log D) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Log of concentration ratio of the unionized species [1] | Log of concentration ratio of all species (ionized + unionized) [1] |

| pH Dependence | No; it is a constant for a neutral compound [2] | Yes; value changes with pH [1] [2] |

| Accounts for Ionization | No [1] | Yes [1] |

| Best Used For | Non-ionizable compounds; basic lipophilicity assessment [5] | Ionizable compounds; predicting behavior in specific biological environments (e.g., GI tract) [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Measurement

Key Experimental Methods for Determining Log P and Log D

Accurately measuring lipophilicity is crucial for data-driven decisions. The following table compares the most common experimental methods.

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shake-Flask [6] [7] | Compound is shaken in a flask containing n-octanol and a pH-buffered water phase. After separation, the concentration in each phase is measured [6]. | Considered a gold standard; accurate results [7]. | Labor-intensive; requires relatively pure compounds; limited measurement range (typically -2 < Log P < 4) [7]. |

| Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) [6] [7] | The retention time of a compound on a non-polar stationary phase is measured and correlated with the retention times of standards with known Log P values to create a calibration curve [7]. | High-throughput; small sample amount; low purity requirement; broad detection range (can measure Log P > 6) [7]. | Provides an indirect measurement; requires a calibration curve with standards [6]. |

| Potentiometric Titration [6] | The sample is dissolved in a water-n-octanol mixture and titrated with an acid or base. The logD profile is determined from the titration curve [6]. | Can directly provide a logD-pH profile. | Limited to compounds with acid-base properties; requires high sample purity [6]. |

Standardized Workflow for the Shake-Flask Method

The shake-flask method is a foundational technique for measuring Log P and Log D. The diagram below outlines the general workflow.

Detailed Methodology [6] [7] [3]:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare n-octanol and an aqueous buffer solution at the desired pH (e.g., pH 7.4 for physiological relevance). Pre-saturate the octanol with water and the water with octanol to prevent volume shifts during the experiment.

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve an accurately weighable quantity of the test compound (typically ~1 mg) in the prepared solvent system.

- Equilibration: Vigorously shake the mixture for a set period to allow the compound to distribute between the two immiscible phases until equilibrium is reached.

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge the mixture to achieve a clean and complete separation of the octanol and aqueous layers.

- Quantification: Carefully separate the two phases. Analyze the concentration of the compound in each phase using a suitable analytical method, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Calculation: Calculate the Log P (for neutral compounds) or Log D (at the specific pH) using the formula: Log P or D = Log₁₀ (Concentration in octanol / Concentration in water).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| n-Octanol | Standard non-polar solvent that mimics biological membranes [4] [3]. |

| pH-Buffered Water | Aqueous phase; buffer controls pH to simulate biological environments or measure Log D [6]. |

| Analytical Standard Compounds | Compounds with known Log P values for calibrating chromatographic methods like RP-HPLC [7]. |

| HPLC System with UV Detector | Standard equipment for quantifying compound concentration in each phase after separation [7]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Our measured Log D values show high variability between replicates. What could be the cause?

- Incomplete Phase Separation: Ensure the mixture is centrifuged sufficiently for complete separation of the octanol and aqueous layers. Any cross-contamination will lead to significant errors [3].

- Inaccurate pH Control: Log D is highly pH-sensitive. Verify the accuracy of your buffer preparation and confirm the pH of the aqueous phase after equilibration [1] [2].

- Impure Compound or Solvents: Impurities can partition differently and interfere with the analysis. Use compounds of the highest available purity and high-grade solvents [6] [7].

FAQ 2: When should we use RP-HPLC over the traditional shake-flask method?

- For High-Throughput Screening: Use RP-HPLC in early drug discovery when you have a large number of compounds and need rapid, comparative lipophilicity data [7].

- For Compounds with Very High or Low Lipophilicity: The shake-flask method is unreliable for extremely lipophilic (Log P > 4) or hydrophilic (Log P < -2) compounds. RP-HPLC can effectively measure a much wider range [7].

- When Compound Purity or Quantity is Low: RP-HPLC is more robust against impurities and requires a smaller sample amount than the shake-flask method [7].

FAQ 3: Why is Log D at pH 7.4 (Log D7.4) so frequently reported and used? pH 7.4 is the physiological pH of blood plasma. Therefore, Log D7.4 gives the best representation of a drug candidate's lipophilicity at the point of distribution in the bloodstream, providing critical insight into its likely behavior in vivo [6].

The Role of Log P and Log D in Drug Discovery

Interplay with the "Rule of 5" and ADMET Properties

Lipophilicity is a key driver of a compound's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profile [1] [4]. The relationship between these properties, Log P, and Log D is complex.

- Rule of 5 (Ro5): The original Ro5 used Log P (not Log D) as a key parameter, stating that for good oral bioavailability, a compound's Log P should be less than 5 [1]. However, overreliance on Ro5 can cause scientists to miss viable candidates, especially for complex targets [1].

- Moving Beyond Rule of 5: There is a growing interest in compounds "Beyond the Rule of 5" (bRo5), such as macrocycles and protein-based agents. For these, the proposed chemical space includes a calculated Log P between -2 and 10, highlighting that Log P and Log D should be used as guides, not absolute filters [1].

- Balancing Act: As shown in the diagram, lipophilicity critically impacts two opposing properties: aqueous solubility (required for dissolution in blood and bodily fluids) and membrane permeability (required to cross lipid membranes and reach the target site) [4]. A moderate Log D (typically between 2 and 5) is often desirable to balance these needs and achieve optimal oral bioavailability [4] [6].

Advanced Predictive Modeling with AI

Experimental measurement of Log D can be a bottleneck. In-silico prediction models are now leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) to accelerate discovery [6].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can learn complex structure-property relationships to predict Log D directly from molecular structure [6].

- Multitask Learning frameworks simultaneously predict related properties like Log P and pKa, which improves the accuracy and generalization of the Log D model [6].

- Transfer Learning allows models pre-trained on large, related datasets (e.g., chromatographic retention time data) to be fine-tuned for Log D prediction, overcoming the challenge of limited experimental Log D data [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

FAQ 1: Why is there an optimal range for lipophilicity, rather than "the more, the better"?

Excessively high lipophilicity often leads to poor aqueous solubility, which can limit dissolution in the gastrointestinal tract and reduce absorption. Furthermore, overly lipophilic compounds are more likely to undergo non-specific binding to plasma proteins and cellular lipids, which can reduce the free concentration available to engage the therapeutic target and increase the risk of off-target toxicity [8] [9]. The goal is to find a balance where the molecule is soluble enough to be transported in aqueous biological fluids yet lipophilic enough to permeate cellular membranes.

FAQ 2: How can I troubleshoot a compound with good target affinity but poor cellular activity in vitro?

This common issue often points to inadequate cellular permeability. The first step is to determine if the compound's lipophilicity is outside the optimal range.

- If LogP is too low (<0): The compound may be too hydrophilic to passively diffuse through lipid membranes. Consider strategies to increase lipophilicity.

- If LogP is too high (>5): The compound may have poor aqueous solubility or become trapped in membranes. Consider introducing polar groups to improve solubility and desorption from the membrane [10] [11].

- Investigate other causes: The compound might be a substrate for efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp). Assays to test for P-gp efflux are recommended in this scenario [12].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between kinetic and thermodynamic solubility, and which should I prioritize?

Kinetic Solubility is a non-equilibrium measurement, typically obtained from a DMSO stock solution, and indicates the speed of dissolution. It is most useful for early-stage screening to identify compounds with immediate precipitation risks [13]. Thermodynamic Solubility is an equilibrium measurement of the concentration of a saturated solution of the most stable crystalline form. It is critical for predicting in vivo performance and formulating the final drug product [13]. Priority: Use kinetic solubility for early, high-throughput compound prioritization. Rely on thermodynamic solubility for lead optimization and formulation development.

FAQ 4: How does the "Goldilocks" concept apply to larger drug modalities?

The Goldilocks principle extends beyond traditional small molecules. For instance, Goldilocks molecules such as cyclic peptides and spiroligomers are designed to be "just right" in size (1–2 kDa) and structure. They are large enough to target flat protein interfaces that small molecules cannot address, yet possess sufficient rigidity and optimized lipophilicity to potentially achieve cell permeability, a task impossible for large biologics [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Lipophilicity and Permeability Issues

Problem 1: Poor Passive Permeability Despite Good LogP

Symptoms: Low cell-based activity despite high biochemical affinity and a calculated LogP in an acceptable range (e.g., 1-4).

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Hydrogen-Bonding Potential | Calculate or measure the number of H-bond donors/acceptors. Count donors (OH, NH) and acceptors (O, N atoms). | Reduce the number of H-bond donors, or mask them through intramolecular H-bonding in rigidified structures. |

| Molecular Flexibility | Analyze the number of rotatable bonds. | Introduce conformational constraints (e.g., cyclization, introducing ring structures) to reduce the penalty for desolvation. |

| Incorrect Protonation State | Calculate the pKa and determine the dominant microspecies at physiological pH (7.4). | Modify the structure to shift the pKa so the neutral species predominates at the pH of absorption. |

Problem 2: Poor Aqueous Solubility

Symptoms: Low kinetic or thermodynamic solubility in aqueous buffers, leading to erratic assay results and predicted poor absorption.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessively High Lipophilicity | Measure LogD at pH 7.4. A high LogD (>>3) is a key indicator. | Introduce ionizable groups (e.g., amines) or polar, non-ionizable groups (e.g., alcohols, amides). |

| High Crystal Lattice Energy | Perform thermal analysis (DSC) to check for a high melting point. | Introduce groups that disrupt crystal packing, such as bulky substituents or branching, to lower the melting point. |

| Ionization not leveraged | Review solubility at different pH values. | Formulate as a salt (e.g., hydrochloride, sodium salt) of an ionizable compound to dramatically improve solubility. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol 1: Shake-Flask Method for Determining LogP/LogD

Objective: To experimentally determine the partition coefficient (LogP) for neutral compounds or the distribution coefficient (LogD) for ionizable compounds at a specific pH.

Principle: This method relies on the partitioning of a compound between an organic phase (typically 1-octanol, which mimics lipid membranes) and an aqueous buffer phase. The concentration in each phase is measured after equilibrium is reached [13] [15].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- n-Octanol: Pre-saturated with the aqueous buffer phase.

- Aqueous Buffer (e.g., pH 7.4 phosphate buffer): Pre-saturated with n-octanol.

- Compound of Interest: High-purity stock solution.

- HPLC-MS System: For sensitive and specific quantification of analyte concentration.

Method:

- Preparation: Pre-saturate n-octanol and aqueous buffer by mixing them overnight and allowing them to separate. Use the saturated phases for the experiment.

- Partitioning: Add a known volume of the aqueous buffer (e.g., 1.5 mL) and n-octanol (e.g., 1.5 mL) to a glass vial. Spike the vial with a known amount of the test compound.

- Equilibration: Seal the vial and shake vigorously for 1-2 hours at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) to reach partitioning equilibrium.

- Separation: Centrifuge the vial to achieve complete phase separation.

- Quantification: Carefully sample from both the aqueous and octanol phases. Dilute the samples as necessary and analyze the concentration of the compound in each phase using a validated HPLC-MS method [15].

- Calculation:

- LogP = Log10 ( [Compound]octanol / [Compound]aqueous )

- For LogD, the formula is the same, but the pH of the aqueous phase must be specified (e.g., LogD~7.4~).

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Coarse-Grained (HTCG) Permeability Prediction

Objective: To predict passive permeability coefficients for a large number of compounds using computationally efficient coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations.

Principle: This physics-based model reduces atomic detail to a few interaction sites ("beads"), allowing for high-throughput simulation. The permeability coefficient (P) is calculated from the potential of mean force (PMF, or G(z)) and diffusivity (D(z)) across a model lipid bilayer using the solubility-diffusion model [10].

Materials:

- Software: Martini coarse-grained simulation package.

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster.

- Input: Chemical structures of compounds to be screened.

Method:

- Coarse-Graining: Translate the atomic structure of the drug molecule and the lipid membrane (e.g., DOPC) into their Martini CG representations.

- System Setup: Construct a simulation box containing the CG lipid bilayer in water and insert the CG drug molecule into the water phase.

- Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Calculation: Use an enhanced sampling method (e.g, umbrella sampling) to simulate the drug molecule at various positions (z) along the membrane normal. The average force at each position is integrated to obtain the PMF, G(z).

- Diffusivity Profile: Calculate the local diffusion coefficient, D(z), of the drug molecule at different positions within the membrane.

- Permeability Calculation: Integrate the PMF and diffusivity profiles using the solubility-diffusion equation to obtain the permeability coefficient P [10]: P⁻¹ = ∫ exp[βG(z)] / D(z) dz where β = 1/kBT.

Quantitative Data on Lipophilicity and Permeability

| LogP/LogD Range | Impact on Solubility | Impact on Permeability | Overall Bioavailability Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| <0 (High Polarity) | Very High | Very Low | High (Poor absorption) |

| 0 - 3 (Optimal Range) | Moderate to Good | Good | Low |

| >3 - 5 (High Lipophilicity) | Low | High, but may be limited by desorption | Moderate (Solubility-limited absorption) |

| >5 (Very High) | Very Poor | Very High, but significant non-specific binding | High (Solubility and clearance issues) |

| Compound | Substituent | Solubility in Buffer pH 7.4 (mol·L⁻¹) | LogD (1-octanol/buffer pH 7.4) | Antifungal MIC (C. parapsilosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | -CH₃ | 1.98 × 10⁻³ | Optimal for absorption | 0.5 μg/mL |

| II | -F | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | 0.1 μg/mL |

| III | -Cl | 0.67 × 10⁻⁴ | Data Not Provided | 0.25 μg/mL |

| Fluconazole | Reference | - | - | 2.0 μg/mL |

Visualizing the Lipophilicity-Permeability Relationship

Diagram: The Goldilocks Principle in Drug Permeability

Diagram: Structure-Tissue Exposure-Activity Relationship (STAR)

Lipophilicity's Broad Influence on Key ADMET Parameters

Core Concepts: Lipophilicity and ADMET

Frequently Asked Questions

What is lipophilicity and why is it critical in drug discovery? Lipophilicity, most commonly measured as LogP (partition coefficient), represents the ratio at equilibrium of a compound's concentration between an oil phase and a water phase. It is a fundamental physicochemical parameter that significantly influences all key ADMET properties: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity [16]. A drug candidate must demonstrate not only sufficient efficacy but also appropriate ADMET properties at therapeutic doses, and lipophilicity serves as a principal modulator of these characteristics [17].

How does lipophilicity affect drug absorption? Lipophilicity plays a crucial dual role in drug absorption. Sufficient lipophilicity enables drugs to cross biological membranes such as the gastrointestinal mucosa. However, excessive lipophilicity can lead to poor aqueous solubility, limiting dissolution and absorption. For optimal intestinal absorption, compounds need a balanced lipophilicity that allows membrane permeation without compromising solubility [18] [19].

What is the relationship between lipophilicity and drug distribution? Lipophilicity strongly influences how drugs distribute throughout the body. More lipophilic drugs more readily penetrate cell membranes and enter cells or fatty tissues. This can be beneficial for drugs requiring intracellular action but problematic for drugs needing maintained bloodstream concentrations, as it may lead to uneven distribution and accumulation in fatty tissues [18]. In obese patients, the volume of distribution increases disproportionately for highly lipophilic drugs, significantly prolonging elimination half-life [20].

How does lipophilicity impact drug metabolism and excretion? Higher lipophilicity typically allows drugs to pass more easily through the liver's metabolic enzyme systems, particularly cytochrome P450 enzymes, leading to faster formation of excretable metabolites [18]. Lipophilicity also determines clearance routes—more hydrophilic compounds tend toward renal excretion, while more lipophilic compounds favor hepatic elimination [21]. This has direct implications for dose-limiting toxicity in different organs.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Promising in vitro compound shows poor oral bioavailability. Potential Lipophilicity-Related Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive lipophilicity (LogP >5) causing poor aqueous solubility and dissolution rate.

- Solution: Introduce polar functional groups or reduce hydrophobic surface area to lower LogP to optimal range (1-3).

- Cause: Inadequate lipophilicity preventing efficient membrane crossing.

- Solution: Carefully increase lipophilicity through strategic molecular modifications while monitoring solubility.

Problem: Drug candidate shows unexpected tissue accumulation and prolonged half-life. Potential Lipophilicity-Related Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive lipophilicity leading to sequestration in adipose tissues.

- Solution: Reduce LogP through molecular modification; aim for moderate lipophilicity (LogP 2-4).

- Cause: High plasma protein binding related to lipophilic character.

- Solution: Introduce ionizable groups or reduce hydrophobic regions to decrease protein binding.

Problem: Drug demonstrates nephrotoxicity or hepatotoxicity in preclinical studies. Potential Lipophilicity-Related Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: For nephrotoxicity: excessively low lipophilicity directing predominant renal clearance and kidney uptake.

- Solution: Increase lipophilicity to shift clearance route toward hepatic pathways [21].

- Cause: For hepatotoxicity: high lipophilicity leading to excessive liver accumulation and metabolism.

- Solution: Moderate lipophilicity to balance clearance routes; consider structural modifications to reduce reactive metabolite formation.

Quantitative Guidance and Optimal Ranges

Lipophilicity Parameters and Their Interpretation

Table 1: Key Lipophilicity Parameters and Their Significance

| Parameter | Description | Optimal Range | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| LogP | Partition coefficient for unionized compound | 1-5 (ideal: 1-3) | Predicts membrane permeability and distribution |

| LogD | Distribution coefficient at specific pH (usually 7.4) | Varies by target | Better predictor of in vivo behavior for ionizable compounds |

| Chromatographic RM0 | Experimentally derived lipophilicity index | Compound-specific | Useful for relative comparison within chemical series |

| ΔLogP | Difference between octanol/water and other solvent systems | Variable | Indicates conformer-specific partitioning behavior |

Lipophilicity Influence on Key ADMET Properties

Table 2: Lipophilicity Relationships with Critical ADMET Properties

| ADMET Property | Impact of Low Lipophilicity | Impact of High Lipophilicity | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Intestinal Absorption | Poor membrane permeability | Poor dissolution; stuck in membranes | LogP 1-3 [19] |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration | Limited CNS access | Non-specific binding; reduced free fraction | LogP ~2 [22] |

| Plasma Protein Binding | Generally lower binding | Extensive binding; reduced free drug | Moderate LogP preferred |

| Metabolic Clearance | Often renal clearance dominant | Hepatic metabolism predominant; faster turnover | Balanced for desired clearance route |

| Tissue Distribution | Limited tissue penetration | Accumulation in fatty tissues; increased volume of distribution | LogP 1-3 for even distribution |

| hERG Inhibition/Cardiotoxicity Risk | Generally lower risk | Increased risk with LogP >3 [19] | LogP <3 preferred |

Experimental Determination and Optimization

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Lipophilicity Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol/Water System | Gold standard for LogP determination | Shake-flask method for equilibrium partitioning |

| RP-TLC (C18 plates) | Chromatographic lipophilicity assessment | High-throughput screening of compound series [23] |

| RP-HPLC with C18 columns | Accurate LogP determination | Reliable alternative to shake-flask method [23] |

| PAMPA Assay Systems | Passive membrane permeability prediction | Early absorption screening |

| Caco-2 Cell Lines | Intestinal absorption prediction | Transporter-mediated absorption studies [19] |

| MDCK-MDR1 Cell Lines | Blood-brain barrier penetration assessment | CNS drug development [19] |

| In silico Prediction Tools | Computational LogP estimation | Early design phase screening [17] [19] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Lipophilicity by RP-TLC Method

Materials and Reagents:

- RP-18 TLC plates (e.g., Merck Silica Gel 60 RP-18 F254S)

- Acetone-TRIS buffer (pH 7.4) mobile phase in varying ratios

- Standard compounds with known LogP values for calibration

- Chromatography chamber saturated with mobile phase vapor

- UV lamp for visualization (254 nm or 366 nm)

Procedure:

- Prepare mobile phases with acetone:TRIS buffer ratios from 40:60 to 80:20 (v/v)

- Spot test compounds and standards on RP-18 plates

- Develop chromatograms in saturated chambers until mobile phase front reaches 8 cm

- Dry plates and detect spots under appropriate UV wavelength

- Calculate RM values using formula: RM = log(1/RF - 1)

- Plot RM values against organic modifier concentration and extrapolate to zero concentration to obtain RM0 [23]

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If spots show tailing, reduce sample concentration or use different detection method

- If RF values are too high/low, adjust organic modifier range accordingly

- Always include internal standards for method validation

Protocol 2: Shake-Flask Method for LogP Determination

Materials and Reagents:

- n-Octanol saturated with TRIS buffer (pH 7.4)

- Aqueous buffer saturated with n-Octanol

- HPLC system with UV detection for concentration measurement

- Centrifuge tubes with tight-sealing caps

- Mechanical shaker and temperature-controlled centrifuge

Procedure:

- Pre-saturate octanol and aqueous phases by mixing equal volumes overnight

- Separate the phases after saturation

- Dissolve test compound in both phases to appropriate concentration

- Mix equal volumes of both phases in sealed tubes

- Shake vigorously for 24 hours at constant temperature (25°C)

- Centrifuge to separate phases completely

- Measure compound concentration in both phases using HPLC-UV

- Calculate LogP = log10(Coctanol/Caqueous) [16]

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If compound concentration is too low for detection, consider increasing initial concentration

- If emulsion forms during shaking, extend centrifugation time or moderate shaking intensity

- Always run controls to account for adsorption to container walls

Advanced Concepts and Strategic Optimization

Lipophilicity Optimization Pathways

Lipophilicity Optimization Workflow

Contemporary Challenges and Solutions

The Trend Toward Increased Lipophilicity in Modern Drugs Recent analyses indicate that the average LogP of approved drugs has increased by approximately one unit over the past two decades, representing a tenfold increase in lipophilicity [18]. This trend is driven by the need to target more complex receptors and disease pathways, particularly in oncology and CNS disorders. However, this increase brings formulation challenges that require specialized delivery strategies.

Advanced Formulation Strategies for Highly Lipophilic Compounds For compounds where high lipophilicity is essential for target engagement, several advanced formulation approaches can mitigate associated challenges:

- Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems (LBDDS): Dissolving or suspending drugs in lipid excipients to enhance absorption [18]

- Drug-Loaded Micelles: Utilizing amphiphilic diblock copolymers to solubilize highly lipophilic drugs [18]

- Nanoemulsions and Nanocrystals: Creating nanoscale formulations to improve dissolution and absorption of hydrophobic drugs [18]

Conformer-Specific Lipophilicity: A Novel Optimization Frontier Emerging research demonstrates that individual molecular conformers can exhibit different lipophilicities (logp), distinct from the macroscopic LogP of the compound. This represents a new avenue for rational drug design, where modifying conformational equilibria in water versus lipid environments can optimize drug properties without major structural changes [24].

Integrated ADMET Assessment Framework

Comprehensive ADMET Scoring

The ADMET-score provides a comprehensive index integrating predictions for 18 critical ADMET properties, offering a single metric for compound evaluation during early drug discovery [17]. This scoring system incorporates key lipophilicity-influenced endpoints including:

- Ames mutagenicity

- Caco-2 permeability

- CYP450 inhibition profiles

- hERG inhibition

- Human intestinal absorption

- P-glycoprotein substrate/inhibition

Strategic Balance in Lipophilicity Optimization

Successful drug development requires balancing lipophilicity to optimize the complete ADMET profile while maintaining target engagement. The following strategic principles should guide optimization efforts:

- Target-Informed Optimization: CNS targets typically require moderate lipophilicity (LogP ~2) for blood-brain barrier penetration, while intracellular targets may tolerate higher values [22] [16]

- Multi-Parameter Optimization: Use tools like probabilistic scoring to simultaneously optimize lipophilicity with other critical properties rather than sequential optimization

- Early Experimental Validation: Computational predictions should be complemented with experimental measurements, particularly for compounds with complex ionization or conformational properties

- Formulation-Aware Design: Consider feasible formulation strategies when lipophilicity requirements push compounds beyond ideal ranges for conventional dosage forms

The strategic optimization of lipophilicity remains one of the most powerful approaches for addressing ADMET challenges in modern drug discovery, enabling the transformation of potent bioactive compounds into viable therapeutic agents.

FAQs: Understanding Lipophilicity and Its Impact

What is molecular obesity, and why is it a concern in drug design? Molecular obesity refers to the trend of increasing lipophilicity (fat-liking property) in modern small-molecule drug candidates. This is characterized by a high partition coefficient (LogP/LogD). Excessive lipophilicity is a major concern because it often leads to poor aqueous solubility, increased risk of off-target effects and promiscuity, higher metabolic clearance, and ultimately, a higher likelihood of compound failure in development [25] [26] [27].

How does lipophilicity affect the pharmacokinetics (PK) of a drug candidate? Lipophilicity has a profound and complex impact on PK. It influences all aspects of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME). The table below summarizes the general relationships, though these trends can be context-dependent [27].

Table 1: The Impact of Lipophilicity on Drug-Like Properties

| Lipophilicity (Log D7.4) | Common Impact on Solubility & Permeability | Common In Vivo Impact |

|---|---|---|

| < 1 | High solubility; Low permeability | Low absorption and bioavailability; Possible renal clearance |

| 1 – 3 | Moderate solubility; Moderate permeability | Potential for good absorption and bioavailability |

| 3 – 5 | Low solubility; High permeability | Variable oral absorption; Moderate to high metabolism |

| > 5 | Poor solubility; High permeability | Poor oral absorption; High metabolism; High volume of distribution |

I need to prolong my drug's half-life. Is simply reducing lipophilicity a reliable strategy? Not necessarily. While reducing lipophilicity can lower clearance (CL), it often also reduces the volume of distribution (Vd,ss). Since half-life is a function of both volume and clearance (T~1/2~ = 0.693 • Vd,ss / CL), the net effect on half-life can be negligible. A more effective strategy is to identify and address specific metabolic soft-spots in the molecule, which can lower clearance without significantly impacting the volume of distribution [26].

What formulation strategies can help with highly lipophilic drugs? For highly hydrophobic drugs, traditional tablet formulation can be challenging. Several advanced delivery strategies can be employed:

- Drug Nanocrystals: The compound is ground into nanocrystals, which are more easily absorbed, and then mixed with excipients like methylcellulose [25].

- Nanoemulsions: Forming oil-in-water emulsions with nanoscale droplets can improve the delivery of hydrophobic drugs. Methylcellulose can act as an amphiphilic stabilizer in these systems [25].

- Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems (LBDDS): Dissolving or suspending the drug in lipid excipients. A common application is drug-loaded micelles, where amphiphilic diblock copolymers (e.g., PEG-PLA) form micelles that encapsulate the lipophilic drug in their hydrophobic core [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Aqueous Solubility

Symptoms:

- Low measured kinetic or thermodynamic solubility in aqueous buffers.

- Precipitate formation in biological assay buffers.

- Poor exposure in vivo despite good permeability.

Recommended Actions:

- Modulate Lipophilicity: Consider introducing polar functional groups (e.g., -OH, -NH~2~, carboxylic acids) or reducing alkyl chain length to lower LogD. Be mindful that this may affect permeability and target potency [25] [27].

- Investigate Formulation Options:

- Protocol for Nanoemulsion Formation: Mix the hydrophobic drug with an amphiphilic excipient like methylcellulose in an oil phase. Use ultrasonic waves to generate nanoscale oil droplets. This emulsion can be converted into a gel by dripping the liquid into a hot water bath, where it solidifies within milliseconds. After drying, drug nanocrystals uniformly distributed in a methylcellulose matrix are obtained [25].

- Utilize Lipid-Based Systems: Explore drug-loaded micelles using diblock copolymers [25].

Table 2: Strategies for Solubility and Permeability Issues

| Problem | Root Cause | Corrective Action | Trade-off / Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Solubility | Excessive lipophilicity (High LogD) | Introduce polar groups; Formulate as nanocrystals or nanoemulsions [25]. | May reduce cell membrane permeability. |

| Low Permeability | Insufficient lipophilicity (Low LogD) | Carefully increase lipophilicity within the optimal range (e.g., LogD 1-3) [27]. | Can decrease solubility and increase metabolic clearance [26]. |

| High Metabolic Clearance | Presence of metabolic soft-spots; High LogD | Identify and block soft-spots (e.g., via -F, -Cl substitution); Consider reducing LogD [26]. | May require significant synthetic effort and can impact potency. |

Problem: High Off-Target Promiscuity and hERG Inhibition

Symptoms:

- Activity in counter-screening panels or broad pharmacological profiling.

- Specific inhibition of the hERG potassium channel, predicting a risk for cardiac arrhythmia.

Recommended Actions:

- Reduce Lipophilicity: Data consistently shows that drug promiscuity and hERG potency increase with lipophilicity. Aim to keep cLogP below 2.5-3 to minimize this risk [26] [27].

- Introduve Polar Interactions: Adding hydrogen bond donors or acceptors can improve specificity for the primary target over off-targets.

Problem: Inefficient Half-Life Optimization

Symptoms:

- Short in vivo half-life requiring frequent dosing.

- Structural modifications that lower clearance but fail to extend half-life.

Recommended Actions:

- Analyze the Clearance/Volume Interplay: Do not focus solely on reducing clearance. Use matched molecular pair (MMP) analysis to identify transformations that improve metabolic stability (lower CL~u~) without drastically reducing the unbound volume of distribution (Vd,ss,u) [26].

- Target Metabolic Soft-Spots: The probability of prolonging half-life is significantly higher (82%) when metabolic stability is improved without decreasing lipophilicity, compared to a generic lipophilicity reduction (30% probability) [26]. Focus on subtle point modifications, such as replacing a metabolically labile methyl group with a fluorine atom.

Experimental Protocols & Data Interpretation

Protocol: Measuring and Interpreting Lipophilicity (LogD)

Objective: To determine the distribution coefficient of a compound at pH 7.4, simulating physiological conditions.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- n-Octanol: Simulates lipid membranes.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4: Simulates aqueous physiological environment.

- Test compound stock solution in DMSO.

- HPLC system with UV/VIS detector or LC-MS for concentration analysis.

Methodology:

- Pre-saturate the PBS and n-octanol by mixing them together overnight and allowing them to separate.

- Add a known concentration of the test compound to a vial containing a defined volume ratio (e.g., 1:1) of pre-saturated PBS and n-octanol.

- Shake the mixture vigorously for a set period (e.g., 1 hour) to reach equilibrium.

- Centrifuge the mixture to achieve complete phase separation.

- Carefully sample from both the aqueous (PBS) and organic (n-octanol) layers.

- Quantify the concentration of the compound in each phase using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV).

- Calculate LogD~7.4~ using the formula: LogD~7.4~ = Log~10~ (Concentration in n-octanol / Concentration in PBS).

Protocol: High-Throughput Metabolic Stability Assay in Hepatocytes

Objective: To determine the intrinsic metabolic clearance of a compound using rat or human hepatocytes.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cryopreserved or fresh hepatocytes.

- Williams' E Medium or other appropriate incubation buffer.

- Test compound and positive control compounds (e.g., Verapamil, Propranolol).

- Stopping solution (e.g., acetonitrile with internal standard).

- LC-MS/MS system for quantitative analysis.

Methodology:

- Thaw and viability-check hepatocytes according to standard protocols.

- Dilute hepatocytes to a standard density (e.g., 0.5-1.0 x 10^6^ viable cells/mL) in incubation buffer.

- Incubate the test compound (typically at 1 µM) with the hepatocyte suspension at 37°C.

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes), remove an aliquot of the incubation mixture and quench the reaction with ice-cold stopping solution.

- Centrifuge the quenched samples to precipitate proteins and analyze the supernatant by LC-MS/MS to determine the parent compound concentration remaining at each time point.

- Plot the natural logarithm of the parent compound concentration versus time. The slope of the linear phase is the intrinsic clearance (CL~int~).

Visualizing the Lipophilicity Optimization Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing issues related to high lipophilicity in drug discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Lipophilicity and ADME Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| n-Octanol & PBS Buffer | Experimental LogD determination | Mimics the partitioning between lipid and aqueous physiological environments; the gold standard for measuring lipophilicity [27]. |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | In vitro metabolic stability studies | Used to predict in vivo metabolic clearance; provides a full complement of hepatic metabolizing enzymes [26]. |

| Methylcellulose | Formulation excipient | An amphiphilic polymer used to enhance the solubility and dissolution of hydrophobic drugs in nanocrystal and nanoemulsion formulations [25]. |

| Diblock Copolymers (e.g., PEG-PLA) | Lipid-based drug delivery | Forms drug-loaded micelles; the hydrophobic core (e.g., PLA) encapsulates lipophilic drugs, while the hydrophilic shell (e.g., PEG) ensures solubility and stability [25]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Bioanalysis | Essential for quantifying drug concentrations in complex matrices (e.g., from solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability assays) with high sensitivity and specificity [26]. |

Foundational Concepts and FAQs

What is Lipinski's Rule of 5?

Lipinski's Rule of 5 (RO5) is a rule of thumb used in drug discovery to evaluate the drug-likeness of a chemical compound, predicting whether it is likely to have good oral bioavailability [28] [29]. It states that poor absorption or permeability is more likely when a compound violates more than one of the following criteria [28] [29] [30]:

- Molecular weight less than 500 Daltons

- Partition coefficient (Log P) less than 5

- No more than 5 hydrogen bond donors (sum of OH and NH groups)

- No more than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors (sum of N and O atoms)

The rule's name originates from the fact that all criteria involve the number five or its multiples [28] [29]. It was formulated based on the observation that most orally administered drugs are relatively small and moderately lipophilic molecules [28].

Why is the Rule of 5 so important in drug development?

The RO5 is a crucial early-stage filter because it describes molecular properties important for a drug's pharmacokinetics in the human body—specifically, its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [28]. Candidate drugs that conform to the RO5 tend to have lower attrition rates during clinical trials, thereby increasing their chance of reaching the market [28]. It helps guide medicinal chemists during lead optimization to maintain drug-like physicochemical properties while increasing a compound's activity and selectivity [28] [30].

My compound violates one or more of the Rule of 5 criteria. Does this mean it will fail?

Not necessarily. The rule predicts that a compound with more than one violation is more likely to have poor absorption, but it is not an absolute predictor of failure [28] [31]. Many effective drugs violate the rule. The likelihood of poor absorption increases with the number of rules broken and the extent to which they are exceeded [30]. A 2023 analysis found that around 66% of oral drugs approved since 1997 conform to the RO5, meaning a significant portion (34%) of successful drugs do not strictly adhere to it [31].

Table 1: Key Rule of 5 Parameters and Their Rationale

| Parameter | Threshold | Physicochemical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | < 500 Da | Increasing MW reduces aqueous solubility and impedes passive diffusion through lipid membranes [30]. |

| Partition Coefficient (Log P) | < 5 | High lipophilicity (Log P > 5) decreases aqueous solubility, reducing concentration available for absorption [30]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | ≤ 5 | H-bonds increase aqueous solubility but must be broken for membrane permeation; more donors reduce partitioning into the lipid bilayer [30]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | ≤ 10 | A high number of acceptors increases solubility and reduces permeability by increasing the energy required to desolvate the molecule [28]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

My lead compound is active but has poor oral absorption. Which parameters should I investigate first?

Begin your troubleshooting by profiling your compound against the core RO5 parameters. The two least-followed criteria in approved drugs are Molecular Weight and LogP, making them common culprits for absorption issues [31]. However, hydrogen bond-related parameters and rotatable bond counts are typically more consistent in well-absorbed drugs and are also critical to check [31].

Use the following workflow to diagnose and address the most common problems.

My compound violates the Rule of 5 but I cannot alter its core structure. What are my options?

If structural modification is not feasible, several alternative strategies exist:

- Prodrug Approach: Design a prodrug—a modified, inactive version of your compound that violates fewer RO5 criteria. The prodrug is designed for better absorption and is then metabolically converted to the active drug inside the body [32]. This is a common strategy to improve solubility or permeability.

- Targeted Delivery Systems: Investigate advanced formulation strategies. For compounds with low solubility, formulations like nano-crystallization, liposomes, or amorphous solid disperses can enhance dissolution and absorption [33].

- Alternative Administration Routes: Consider if your drug candidate can be developed for non-oral routes (e.g., injectable, inhaled), where the RO5 constraints are less critical [34].

Advanced Frameworks: Going Beyond the Rule of 5

What other rules and classification systems should I use alongside Lipinski's?

The RO5 is a starting point. For a more comprehensive analysis, integrate these established frameworks:

- Veber's Rules: Challenge the 500 MW cutoff and propose that polar surface area (PSA ≤ 140 Ų) and rotatable bonds (≤ 10) are better predictors of good oral bioavailability [28] [31]. These are particularly useful for diagnosing permeability issues.

- The Rule of Three (RO3): Applied earlier in discovery during screening library design. It defines "lead-like" compounds with stricter thresholds (e.g., MW < 300, Log P ≤ 3) to give medicinal chemists more structural space for optimization while still ending up with a drug-like candidate [28].

- BDDCS (Biopharmaceutics Drug Disposition Classification System): This system builds upon the RO5 and is powerful for predicting drug disposition and potential drug-drug interactions for both RO5-compliant and non-compliant compounds [34]. It classifies drugs based on their solubility and metabolism, which helps predict the clinical relevance of transporter effects.

Table 2: Extended Rules for Oral Bioavailability

| Framework | Key Criteria | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Veber's Rules | • Rotatable bonds ≤ 10• Polar Surface Area ≤ 140 Ų | Refining bioavailability prediction, especially for permeability [28]. |

| Ghose Filter | • Log P between -0.4 and 5.6• MW between 180 and 480• Molar refractivity between 40 and 130 | A quantitative extension of RO5 for drug-likeness [28]. |

| Rule of Three (RO3) | • MW < 300• Log P ≤ 3• HBD ≤ 3• HBA ≤ 3• Rotatable bonds ≤ 3 | Defining "lead-like" compounds for building screening libraries [28]. |

| BDDCS | • Combines solubility and extent of metabolism | Predicting drug disposition, transporter effects, and drug-drug interactions [34]. |

The following diagram illustrates how these different frameworks can be integrated into a drug discovery workflow to systematically assess and optimize oral bioavailability.

What are common exceptions to the Rule of 5 that I should be aware of?

Several important therapeutic classes frequently violate the RO5 but can still be successful, often by utilizing active transport mechanisms instead of relying solely on passive diffusion [28] [32].

- Natural Products: Compounds like antibiotics (e.g., vancomycin) or anticancer agents (e.g., paclitaxel) often have high MW and complex structures but are potent therapeutics [28] [32].

- Peptides and Macrolides: These molecules often exceed RO5 limits for MW, HBD, and HBA, but their structural flexibility or specific transporters can facilitate absorption [28] [32].

- CNS Active Agents: Drugs targeting the central nervous system may need higher lipophilicity to cross the blood-brain barrier, leading to Log P violations [32] [35].

- Substrates for Active Transporters: The RO5 assumes passive diffusion is the primary absorption mechanism. However, if a compound is a substrate for an active uptake transporter in the gut, it can be well-absorbed despite multiple RO5 violations [28] [34].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioavailability Assessment

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | An in vitro model of the human intestinal barrier to experimentally assess permeability. |

| Artificial Membrane Assays (PAMPA) | A high-throughput method to predict passive transcellular permeability. |

| ChemAxon Software Tools | Provides calculations for Log P, HBD, HBA, and other physicochemical parameters directly from chemical structure [29]. |

| SwissADME Web Tool | A free online resource for computing key pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness parameters, including RO5 compliance [35]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes | An in vitro system for assessing metabolic stability, a key property influencing oral bioavailability. |

Measuring and Predicting Lipophilicity: From Traditional Assays to Modern AI-Driven Approaches

Lipophilicity, a key physicochemical property in drug discovery, refers to the affinity of a molecule for a lipophilic environment and is crucial for a drug's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). It is commonly described by the logarithm of the n-octanol/water partition coefficient (log P for unionized compounds or log D for ionizable compounds at a specific pH) [21]. The shake-flask method remains an experimental gold standard for its direct determination.

The Critical Role of Lipophilicity in Drug Development

Lipophilicity is a fundamental factor in the rule of five, a widely used tool for assessing drug-likeness during discovery [21]. It significantly impacts a drug candidate's:

- Membrane Permeability and Absorption: Determines the compound's ability to cross biological membranes like the gastrointestinal tract [36].

- Biodistribution and Clearance Route: Higher lipophilicity can decrease kidney uptake and toxicity, steering clearance toward hepatic routes [21].

- Target Affinity and Solubility: While often enhancing affinity for hydrophobic protein pockets, excessive lipophilicity can lead to poor aqueous solubility, limiting oral bioavailability [36].

Balancing lipophilicity is therefore essential for optimizing both the safety and efficacy of drug candidates [21] [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Miniaturized Shake-Flask HPLC Method

The following is a validated, miniaturized protocol for determining the distribution coefficient, adapted for high-throughput analysis [37] [38].

Materials and Equipment

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| n-Octanol | Organic phase simulating lipid membranes. Must be HPLC grade for purity [37]. |

| Aqueous Buffer (e.g., Phosphate Buffer, pH 7.4) | Aqueous phase simulating physiological conditions. pH must be precisely controlled and verified [37]. |

| Drug Solution | The compound of interest, dissolved in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMSO). |

| HPLC System with DAD | For analytical separation and quantification of the drug concentration in the aqueous phase [37] [38]. |

| 2-mL Vials or Shake-Flasks | Container for the miniaturized liquid-liquid extraction. |

| Thermostatted Shaker | Provides consistent and controlled mixing speed, time, and temperature [37]. |

| Centrifuge | Used for rapid and clear phase separation after shaking [37]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Phase Preparation and Saturation: Pre-saturate n-octanol and the aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) with each other by mixing them thoroughly and allowing them to separate before use. This prevents volume changes during the experiment [37].

- Sample Preparation: In a 2-mL vial, combine the pre-saturated n-octanol and buffer at a specific phase ratio (e.g., 1:1). Spike the mixture with a small volume of the drug stock solution [37].

- Equilibration: Securely cap the vials and shake them using a thermostatted shaker for a predetermined time (e.g., 1-2 hours) at a constant speed and temperature (e.g., 25°C) to reach partitioning equilibrium [37].

- Phase Separation: After shaking, centrifuge the vials to achieve a sharp interface between the n-octanol and aqueous layers [37].

- Sampling: Carefully draw a sample from the aqueous phase, ensuring no contamination from the organic phase or the interface [37].

- HPLC Analysis: Determine the concentration of the drug in the aqueous phase using a validated HPLC method. A parallel control sample of the drug in pure buffer is used to determine the initial concentration (C_initial) [37] [38].

Data Analysis and Log D Calculation

The distribution coefficient (Log D) is calculated using the following formula: Log D = Log10 ( (Cinitial - Caqueous) / Caqueous × (Vaqueous / V_organic) )

Where:

- C_initial is the initial concentration of the drug in the aqueous phase (from the control).

- C_aqueous is the concentration of the drug in the aqueous phase after equilibration.

- Vaqueous and Vorganic are the volumes of the aqueous and organic phases, respectively.

Table 2: Example HPLC Method Conditions for Drug Analysis (e.g., IBD drugs)

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Column | C18 Reversed-Phase |

| Mobile Phase | Gradient of Acetonitrile and Buffer (e.g., Phosphate, pH ~3) |

| Flow Rate | 1.0 mL/min |

| Detection | DAD (e.g., 254 nm, 305 nm) |

| Temperature | 25°C |

| Injection Volume | 10-20 µL |

| Sample Diluent | Mobile Phase A or Buffer [37] |

HPLC Troubleshooting Guide for Shake-Flask Analysis

Common HPLC Issues and Solutions

Table 3: HPLC Symptom and Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing | - Basic compounds interacting with silanol groups.- Active sites on the column. | - Use high-purity silica (Type B) or charged surface hybrid (CSH) columns [39] [40].- Add a competing base like triethylamine to the mobile phase [40]. |

| Broad Peaks | - Excessive extra-column volume.- Column degradation or void. | - Use short, narrow internal diameter (0.13 mm) connecting capillaries [40].- Replace the column [40]. |

| Retention Time Drift | - Poor mobile phase or temperature control.- Column not equilibrated. | - Prepare fresh mobile phase daily. Use a column oven [41].- Increase column equilibration time with the new mobile phase [41]. |

| Baseline Noise/Drift | - Air bubbles in system.- Contaminated detector cell or mobile phase. | - Degas mobile phases thoroughly. Purge the system [41].- Flush the detector cell with strong organic solvent. Use HPLC-grade water [41] [40]. |

| Irreproducible Peak Areas | - Air in autosampler syringe or needle.- Sample degradation or evaporation. | - Purge autosampler fluidics. Check for leaking seals [40].- Use a thermostatted autosampler. Ensure vials are properly sealed [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a miniaturized shake-flask method preferred in modern drug discovery? A1: Miniaturization (using 2-mL vials) reduces the consumption of often scarce and expensive drug candidates. It also increases throughput, allowing for the measurement of a large number of compounds more efficiently, which is ideal for early-stage screening [37] [38].

Q2: What are the most critical parameters to control for a reliable Log D measurement? A2: Key parameters include consistent shaking speed and time, precise temperature control, accurate buffer pH, and the n-octanol/buffer phase ratio. Attention to these details ensures the system reaches equilibrium and results are reproducible [37].

Q3: My drug is ionizable. Should I use Log P or Log D? A3: For ionizable drugs, the distribution coefficient (Log D) is the appropriate measure because it accounts for the distribution of all forms of the compound (ionized and unionized) between the two phases at a specific pH. Log P describes only the unionized species [21] [36]. Log D at physiological pH (7.4) is most relevant for predicting ADME properties.

Q4: How can I improve the retention and peak shape of a very polar drug in HPLC analysis? A4: For polar drugs that are poorly retained on standard C18 columns:

- Use a less retentive stationary phase (e.g., C8, C4).

- Employ a highly aqueous mobile phase.

- Consider HILIC (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography) as an alternative separation mode.

- Derivatization of the analyte can also alter its physicochemical properties to improve retention and detectability [42].

Q5: How does lipophilicity directly impact the safety of a targeted radiopharmaceutical therapy? A5: Research has shown that tuning the lipophilicity (log D7.4) of a radiopharmaceutical can effectively modulate its clearance route. Lower lipophilicity was associated with increased kidney uptake, absorbed radiation dose, and acute nephrotoxicity. Conversely, higher lipophilicity reduced kidney uptake and toxicity, shifting clearance toward the hepatic system and improving safety profiles [21]. This principle is critical for balancing efficacy and toxicity in drug candidate research.

The Role of Lipophilicity in Drug Design: A Conceptual Workflow

The following diagram illustrates how the shake-flask method and HPLC analysis are integrated into the drug design and optimization cycle.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

ADMET Predictor

Q1: What should I do if my ADMET Predictor property predictions seem inaccurate for very high-logP compounds? A1: First, check the model's applicability domain assessment provided with the prediction. Models may be less reliable for compounds with logP > 5. Use the built-in "ADMET Risk" module to evaluate lipophilicity-related risks specifically. Ensure you're using the latest version (ADMET Predictor 13) which contains updated AI models trained on premium datasets for improved accuracy [43] [44].

Q2: How can I integrate ADMET Predictor into my automated KNIME workflows? A2: ADMET Predictor 13 provides extended REST APIs and Python scripting support for enterprise automation. You can deploy it as a service and connect via dedicated KNIME components. The API calculates properties at high speed and can be configured to run multi-threaded without consuming additional licenses [44] [45].

RDKit

Q3: Why is my RDKit substructure search running slowly on large chemical libraries? A3: For large datasets, avoid in-memory searches in Python. Instead, use the RDKit PostgreSQL Cartridge which executes chemical queries directly at the database level for optimal performance. Additionally, pre-compute and index molecular fingerprints to accelerate similarity searches [46].

Q4: Can RDKit generate pre-trained ADMET models for immediate use? A4: No, RDKit focuses on cheminformatics infrastructure rather than pre-trained ADMET models. It provides comprehensive molecular descriptors and fingerprints that you can use to build or apply external QSAR models. For immediate predictions, you would need to integrate it with specialized tools or develop your own models using its descriptor calculation capabilities [46].

General Tool Issues

Q5: How do I resolve file format compatibility issues when transferring structures between these platforms? A5: Use the SDF (Structure-Data File) format as it is universally supported. When transferring between RDKit and ADMET Predictor, ensure proper handling of stereochemistry and explicit hydrogens. RDKit's molecule sanitization step can help standardize structures before export [46] [44].

Q6: What steps should I take when predicted properties conflict between different tools? A6: First, verify input structure standardization (tautomers, protonation states, stereochemistry). Check each tool's applicability domain for your specific compounds. Consult the experimental data ranges used to train each model – ADMET Predictor documents its premium training datasets, while RDKit-based models vary by implementation [46] [44] [47].

Troubleshooting Guides

Installation and Setup Issues

Problem: RDKit import errors in Python environment

- Symptoms: ModuleNotFoundError or segmentation faults when importing RDKit

- Solution steps:

- Verify Python version compatibility (check RDKit documentation for supported versions)

- Confirm correct installation using conda:

conda install -c conda-forge rdkit - Check for conflicting packages in your environment

- Validate installation with simple test:

python -c "from rdkit import Chem; print(Chem.rdBase.rdkitVersion)"

Problem: ADMET Predictor license activation failures

- Symptoms: Licensing errors or inability to connect to license server

- Solution steps:

Performance Optimization

Problem: Slow virtual screening with RDKit on large compound libraries

- Symptoms: Long processing times for fingerprint calculations or similarity searches

- Solution steps:

Prediction Accuracy and Validation

Problem: Inconsistent lipophilicity predictions across platforms

- Symptoms: Significant differences in logP/logD predictions between tools

- Solution steps:

- Standardize input structures: Ensure identical tautomeric forms, protonation states, and stereochemistry

- Verify calculation conditions: For logD, ensure consistent pH settings across tools

- Consult experimental benchmarks: Refer to published validation studies for each tool

- Check applicability domains: Each tool has different reliability ranges for molecular properties

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Lipophilicity Prediction Discrepancies

| Issue Cause | Symptoms | Verification Method | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Different calculation algorithms | Consistent prediction bias across compound classes | Compare with experimental values for known standards | Understand algorithm differences and apply appropriate correction factors |

| Structure standardization variations | Inconsistent predictions for tautomers or charged species | Visualize standardized structures in each platform | Pre-standardize structures using consistent rules before prediction |

| pH condition mismatches | logD values varying systematically | Verify pH settings for each prediction | Standardize pH conditions (e.g., pH 7.4 for physiological comparisons) |

| Beyond applicability domain | Poor correlation with experimental data for specific chemotypes | Check model domain of applicability flags | Use alternative tools or models specifically validated for your chemotype |

Experimental Protocols for Lipophilicity Balancing

Protocol 1: Integrated Lipophilicity Optimization Workflow

This protocol uses all three tools to systematically optimize compound lipophilicity while maintaining potency.

Workflow: Lipophilicity Optimization

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation

- Standardize molecular structures in RDKit using

Chem.SanitizeMol() - Generate canonical SMILES for consistent representation across tools

- For salts, strip counterions and generate neutral forms before calculation

- Standardize molecular structures in RDKit using

Initial Profiling

- Compute 200+ molecular descriptors using RDKit's

Descriptorsmodule - Calculate logP using RDKit's built-in methods (

Descriptors.MolLogP) - Run comprehensive ADMET prediction including solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability [44]

- Generate QikProp profile focusing on drug-likeness parameters

- Compute 200+ molecular descriptors using RDKit's

Risk Assessment

- Calculate ADMETRisk score with specific attention to AbsnRisk (absorption risk) and CYP_Risk (metabolism risk) [44]

- Identify which specific structural features contribute most to high lipophilicity

- Use RDKit's structural analysis tools to highlight problematic substructures

Design Modifications

- Apply bioisosteric replacement strategies using RDKit's reaction capabilities

- Consider bridged heterocycles which can counterintuitively reduce lipophilicity in some cases [48]

- Generate analogues with targeted logP reduction while maintaining key pharmacophoric features

Iterative Optimization

- Re-predict properties for modified compounds

- Use matched molecular pair analysis in RDKit to quantify property changes

- Continue until optimal balance achieved (typically logP 1-3 for oral drugs)

Protocol 2: Bridged Heterocycles for Lipophilicity Reduction

Based on AstraZeneca research, bridged saturated heterocycles can sometimes reduce lipophilicity despite adding carbon atoms [48].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Lipophilicity Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Research | Specific Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit Scaffold Analysis | Identifies and compares molecular frameworks | Murcko scaffold decomposition for core lipophilicity assessment | rdkit.Chem.Scaffolds.MurckoScaffold.GetScaffoldForMol(mol) |

| ADMET Predictor AIDD Module | AI-driven drug design for property optimization | Generates novel analogues with improved lipophilicity profiles | Integrated AI-driven drug design engine in ADMET Predictor 13 [43] |

| Bridged Heterocycle Libraries | Provides unusual structural motifs for lipophilicity control | Pre-enumerated bridged piperidines, morpholines, and piperazines | Use KT-474-inspired bridged morpholines for permeability optimization [48] |

| KNIME with RDKit Nodes | Workflow automation for high-throughput analysis | Automated lipophilicity-property relationship modeling | Implement recursive variable selection for solubility prediction [47] |

Workflow: Bridged Heterocycle Evaluation

Experimental Steps:

Identify Modification Sites

- Use RDKit to identify saturated heterocycles (piperidines, morpholines, piperazines) in lead compound

- Analyze current lipophilicity contribution using group contribution methods

Design Bridged Analogues

- Apply bridged structural motifs from clinical candidates like KT-474 (bridged morpholine) or tebideutorexant (bridged piperidine) [48]

- Maintain key hydrogen bond donors/acceptors while introducing bridge

Property Prediction

- Calculate conformational changes using RDKit's 3D conformation generation

- Predict new logP/logD values using ADMET Predictor's updated models

- Assess overall ADMET profile changes, particularly permeability and metabolic stability

Synthetic Feasibility Assessment

- Evaluate synthetic accessibility using RDKit's synthetic complexity score

- Prioritize analogues with feasible synthesis routes

Technical Specifications and Data Comparison

Table 3: Platform Capabilities for Lipophilicity-Focused Research

| Feature | ADMET Predictor 13 | RDKit | QikProp |

|---|---|---|---|

| logP Prediction Methods | AI/ML models trained on premium datasets | Classical group contribution and atomic methods | Comparative molecular field analysis |

| logD Prediction | Yes, with pH profiles and microspecies distribution | Limited, requires external pKa prediction | Yes, at specific pH values |

| Bridged Heterocycle Coverage | Extensive in latest models | Good structural recognition | Varies by version |

| Lipophilicity Optimization Tools | Integrated AIDD module with lipophilicity constraints | Scriptable design with property calculations | Rule-based optimization |

| Throughput | High-speed prediction for virtual libraries | Dependent on implementation, can be optimized | Moderate to high |

| API Access | REST API, Python, KNIME components [44] | Python, C++, Java, KNIME nodes [46] | Varies by distribution |

Table 4: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks for Key Properties

| Property | ADMET Predictor 13 | RDKit | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| logP Prediction Accuracy | R² > 0.90 for diverse test sets [44] | R² ~0.85 for drug-like molecules | Concordance with shake-flask methods |

| Solubility Prediction | Consensus models with uncertainty estimates [44] | QSPR models require external development | RMSE ~0.6-0.7 log S units [47] |

| ADMET Risk Assessment | Comprehensive risk scoring based on WDI analysis [44] | Manual implementation required | Calibrated against successful oral drugs [44] |

| Computational Performance | ~175 properties in seconds per compound [44] | Variable based on descriptors and implementation | Suitable for large virtual libraries |

In modern drug discovery, predicting molecular properties is a fundamental challenge that directly impacts the efficacy and safety of candidate drugs. Deep learning has emerged as a powerful tool for this task, capable of learning complex patterns from molecular data. These models operate on various representations of molecules, including SMILES strings, molecular fingerprints, 2D graphs, and 3D structures. The core challenge lies in selecting and implementing the right architecture for specific drug discovery tasks, particularly when optimizing critical properties like lipophilicity (LogP), which significantly influences a drug's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profile [49] [50].

This technical support center addresses common implementation challenges and provides practical guidance for researchers working with prominent deep learning architectures in cheminformatics: Mol2vec, Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN), and Graph Convolutional Models. The content is framed within the context of balancing lipophilicity in drug candidates, a crucial property that affects solubility, cell membrane permeability, and overall drug-likeness. Excessive lipophilicity can lead to poor aqueous solubility, increased metabolic clearance, and promiscuity, while insufficient lipophilicity may limit membrane permeability and target binding [50] [26].

Key Architectures and Their Applications

Molecular Representation Learning (Mol2vec)

Mol2vec is an unsupervised learning technique that generates meaningful vector representations for molecules, analogous to word2vec in natural language processing. While not explicitly detailed in the search results, it falls under the category of sequence-based representation learning methods that capture molecular features from SMILES strings or other sequential representations.

Common Implementation Issues and Solutions:

Problem: Inability to Capture Complex Molecular Features

- Symptoms: Poor performance on downstream tasks, failure to distinguish structurally similar molecules with different properties.

- Solution: Implement a fusion approach that combines multiple representation types. Research indicates that integrating molecular fingerprints, 2D graphs, 3D structures, and molecular images provides complementary information that significantly enhances prediction accuracy for complex properties like lipophilicity [49]. The DLF-MFF framework demonstrates that multi-type feature fusion outperforms single-representation models across various molecular property prediction tasks [49].

Problem: Limited Generalization Across Scaffolds

- Symptoms: Model performs well on molecules similar to training data but fails on novel structural scaffolds.

- Solution: Utilize scaffold splitting during dataset preparation and augmentation. The ImageMol framework employs scaffold split, random scaffold split, and balanced scaffold split strategies to ensure models learn generalizable features rather than memorizing specific structures [51]. This is particularly important for lipophilicity prediction, where different molecular scaffolds can exhibit significantly different LogP values despite similar atom counts.

Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN)

MPNNs provide a general framework for learning on graph-structured data, making them naturally suited for molecular property prediction where molecules are represented as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) [52] [53]. The key operation in MPNNs is message passing, where nodes iteratively update their representations by aggregating information from their neighbors [52].

Troubleshooting Guide:

Problem: Vanishing Gradients in Deep MPNN Architectures

- Symptoms: Training loss fails to decrease, model performance plateaus at suboptimal levels.

- Solution: Implement residual connections and gated recurrent units. The Gated Graph Sequence Neural Network (GGS-NN) extends MPNNs by incorporating gated recurrent units (GRU) as update functions, which helps maintain gradient flow through multiple message passing layers [52]. This is crucial for capturing long-range interactions in larger drug-like molecules where lipophilicity depends on complex atomic interactions across the molecular structure.

Problem: Inadequate Representation of Molecular Properties

- Symptoms: Model fails to predict key molecular properties despite sufficient training.

- Solution: Implement comprehensive atom and bond featurization. Use the following feature sets for optimal performance [53]:

- Atom features: Symbol (element), number of valence electrons, number of hydrogen bonds, orbital hybridization.

- Bond features: Bond type (single, double, triple, aromatic), conjugation.

Experimental protocols should include these feature definitions to ensure the model captures essential chemical information relevant to lipophilicity, such as electron distribution and bond types that influence molecular polarity [53].

Problem: Inefficient Processing of Molecular Graphs

- Symptoms: Long training times, memory issues with large molecular datasets.

- Solution: Optimize the graph generation pipeline using RDKit. The following protocol ensures efficient processing [53]:

The following diagram illustrates the complete MPNN workflow for molecular property prediction, from raw SMILES input to final lipophilicity prediction:

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) operate by performing spectral graph convolutions using the graph Laplacian matrix. A GCN layer can be formally expressed as [52]:

H = σ(D̃⁻¹/²ÃD̃⁻¹/²XΘ)

Where H is the output node representations, σ is the activation function, Ã is the adjacency matrix with self-loops added, D̃ is the degree matrix of Ã, X is the input node features, and Θ is the trainable weight matrix.

Common Implementation Issues and Solutions:

Problem: Oversmoothing in Deep GCN Architectures

- Symptoms: All node representations become indistinguishable after multiple layers, reducing model discriminative power.

- Solution: Implement sparse connections and attention mechanisms. Graph Attention Networks (GATs) address this by introducing attention mechanisms that assign different weights to different neighbors [52]. The attention coefficients αₘₙ are computed as [52]:

αₘₙ = exp(LeakyReLU(aᵀ[Wxm ‖ Wxn ‖ emn])) / Σk∈Nm exp(LeakyReLU(aᵀ[Wxm ‖ Wxk ‖ emk]))

This is particularly valuable for lipophilicity prediction where specific functional groups disproportionately influence the overall LogP value.

Problem: Limited Expressivity for Molecular Tasks

- Symptoms: Inability to distinguish certain molecular structures that have different properties.

- Solution: Enhance GCNs with 3D structural information. Standard 2D GCNs have limited ability to express 3D molecular structure, which is crucial for accurate property prediction. The 3D-GCN architecture incorporates 3D molecular topology to more accurately predict molecular properties from 3D molecular graphs [49]. For lipophilicity prediction, this 3D information can capture molecular folding and steric effects that influence hydrophobicity.

Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures

The table below summarizes the performance of various deep learning architectures on key molecular property prediction tasks, including lipophilicity prediction:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Property Prediction Models

| Model Architecture | Representation Type | BBB Penetration (AUC) | Tox21 (AUC) | Lipophilicity (RMSE) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageMol [51] | Molecular Image | 0.952 | 0.847 | 0.625 | Unsupervised pretraining on 10M compounds |

| DLF-MFF [49] | Multi-type Fusion | N/A | N/A | ~0.72 | Integrates 2D, 3D, fingerprints, and images |

| MPNN [53] | Graph | 0.92 (BBBP) | N/A | N/A | Natural graph representation of molecules |