Assessing Validity in Indirect Treatment Comparisons: A Comprehensive Guide to Common Comparator Methods and Best Practices

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for assessing the validity of Indirect Treatment Comparisons (ITCs) anchored by a common comparator.

Assessing Validity in Indirect Treatment Comparisons: A Comprehensive Guide to Common Comparator Methods and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for assessing the validity of Indirect Treatment Comparisons (ITCs) anchored by a common comparator. With head-to-head randomized controlled trials often unavailable, ITCs are indispensable for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) submissions and demonstrating comparative effectiveness. We explore the foundational assumptions, methodologies, and evolving guidelines from global HTA bodies. The content covers practical strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls like heterogeneity and bias, and emphasizes validation techniques to ensure robust, defensible evidence for healthcare decision-making.

The Bedrock of Valid ITCs: Core Principles, Definitions, and the Central Role of the Common Comparator

Defining Indirect Treatment Comparisons and the Common Comparator Paradigm

In the realm of evidence-based medicine and health technology assessment, Indirect Treatment Comparisons (ITCs) have emerged as a crucial methodological approach when direct head-to-head evidence is unavailable. An ITC provides an estimate of the relative treatment effect between two interventions that have not been compared directly within randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [1]. This is typically achieved through a common comparator that acts as an anchor—often a standard drug, placebo, or control intervention—enabling the indirect comparison of treatments that lack direct comparative evidence [1].

The fundamental scenario for an ITC involves three interventions: if Treatment A has been compared to Treatment C in one trial, and Treatment B has been compared to Treatment C in another trial, then researchers can statistically derive an indirect comparison between Treatment A and Treatment B [1]. This paradigm has become increasingly important for healthcare decision-makers who need to compare all relevant interventions to inform reimbursement and treatment recommendations, particularly when direct comparisons are ethically challenging, economically unviable, or practically impossible to conduct [1] [2].

The Common Comparator Paradigm

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

The common comparator paradigm relies on a connected network of evidence where two or more interventions share a common reference point. The validity of this approach depends on several key assumptions that must be rigorously assessed to ensure the reliability of results.

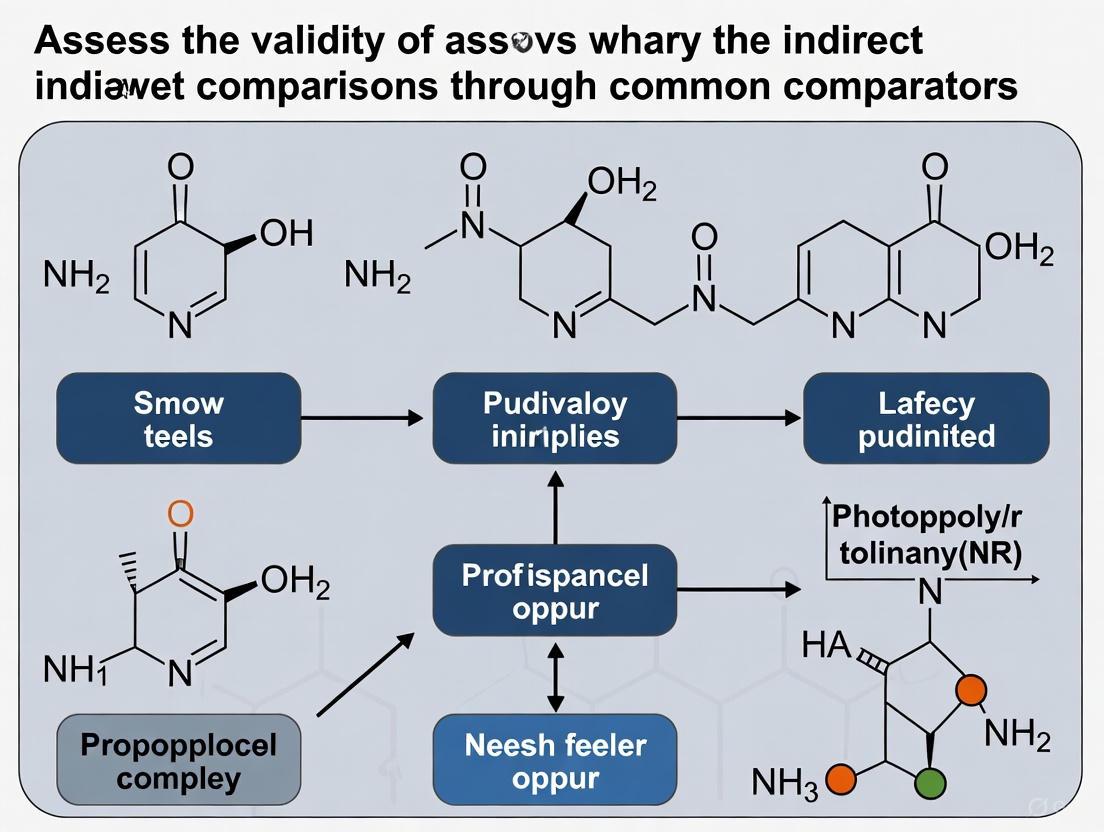

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow underlying the common comparator paradigm in indirect treatment comparisons:

Core Methodological Assumptions

The validity of the common comparator paradigm rests on three fundamental assumptions that must be critically evaluated:

Similarity/Transitivity: This assumption requires that the trials being compared are sufficiently similar in their clinical and methodological characteristics to permit a fair comparison [1] [3]. This encompasses factors such as patient baseline characteristics, trial design, outcome definitions, and measurement methods. Violation of this assumption introduces significant uncertainty into ITC results [1] [4].

Homogeneity: This refers to the similarity within the sets of trials comparing each intervention with the common comparator. There should be no substantial statistical heterogeneity within the A vs. C and B vs. C trial networks that would undermine the validity of pooling their results [5] [4].

Consistency: When both direct and indirect evidence exists for the same comparison, the consistency assumption requires that these different sources of evidence produce similar treatment effect estimates [5] [4]. Significant discrepancies between direct and indirect evidence may indicate violation of underlying assumptions or methodological biases.

Methods for Indirect Treatment Comparisons

Numerous ITC techniques have been developed, each with distinct methodological approaches, data requirements, and applications. A recent systematic literature review identified seven primary ITC techniques used in contemporary research [2].

Table 1: Primary Indirect Treatment Comparison Methods

| ITC Method | Key Features | Data Requirements | Common Applications | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) | Simultaneously compares multiple interventions; most frequently described method (79.5% of articles) [2] | Aggregate data from multiple trials | Multiple intervention comparisons or treatment ranking [2] [3] | Consistency, homogeneity, similarity [3] |

| Bucher Method | Adjusted indirect comparison for pairwise comparisons through common comparator [3] [6] | Aggregate data from trials with common comparator | Pairwise indirect comparisons [2] [3] | Constancy of relative effects (homogeneity, similarity) [3] |

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) | Uses IPD from one treatment to match baseline characteristics of aggregate data from another [2] [7] | IPD from one trial plus aggregate data from another | Pairwise comparisons with population heterogeneity; single-arm studies [2] [3] | Constancy of relative or absolute effects [3] |

| Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC) | Predicts outcomes in aggregate data population using outcome regression model based on IPD [2] [3] | IPD from one trial plus aggregate data from another | Pairwise ITC with considerable population heterogeneity [3] | Constancy of relative or absolute effects [3] |

| Network Meta-Regression | Explores impact of study-level covariates on treatment effects [2] [3] | Aggregate data with covariate information | Multiple ITC with connected network to investigate effect modifiers [3] | Conditional constancy of relative effects with shared effect modifier [3] |

Selection Framework for ITC Methods

Choosing the appropriate ITC method depends on several factors, including the available data, network structure, and specific research question. The following framework guides method selection:

Table 2: ITC Method Selection Framework

| Scenario | Recommended Methods | Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connected network with aggregate data only | Bucher method, NMA [2] | Preserves within-trial randomization without requiring IPD | Assess homogeneity and transitivity assumptions thoroughly [3] [4] |

| Single-arm studies or substantial population heterogeneity | MAIC, STC [2] [7] | Adjusts for cross-trial differences in patient populations | Requires IPD for at least one treatment; cannot adjust for unobserved differences [3] [7] |

| Effect modification by known covariates | Network meta-regression [2] [3] | Explores impact of study-level covariates on treatment effects | Requires multiple trials per comparison; limited with sparse networks [3] |

| Multiple interventions comparison | NMA [2] [3] | Simultaneously compares all interventions and provides ranking | Consistency assumption must be verified; complexity increases with network size [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflows

Protocol for Conducting Adjusted Indirect Comparisons

The Bucher method, one of the foundational approaches for ITC, follows a specific statistical protocol [6] [5]:

- Identify direct evidence: Establish the available direct comparisons (A vs. C and B vs. C) from separate RCTs.

- Calculate effect estimates: Compute the relative treatment effects for each direct comparison (e.g., log odds ratios, risk ratios, or mean differences) with their standard errors.

- Compute indirect effect: The indirect estimate for A vs. B is derived using the formula: EffectA vs. B = EffectA vs. C - EffectB vs. C

- Calculate variance: The variance of the indirect estimate is the sum of the variances of the two direct estimates: Var(EffectA vs. B) = Var(EffectA vs. C) + Var(EffectB vs. C)

- Construct confidence intervals: Using the calculated effect estimate and variance, construct 95% confidence intervals for the indirect comparison.

This method preserves the within-trial randomization and provides a statistically valid approach for indirect comparison, though it depends heavily on the similarity assumption [6] [5].

Protocol for Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC)

MAIC has emerged as a valuable technique when IPD is available for at least one treatment [7]:

- Obtain IPD: Acquire individual patient data from trials of one treatment (e.g., Treatment A).

- Identify aggregate data: Collect published aggregate baseline characteristics and outcomes for the comparator treatment (Treatment B).

- Define target population: Typically, the population represented in the aggregate data serves as the target population.

- Calculate weights: Using propensity score methodology, calculate weights for each patient in the IPD such that the weighted distribution of baseline characteristics matches the aggregate distribution of the comparator trial.

- Analyze outcomes: Apply the calculated weights to the outcomes in the IPD and compare the weighted outcomes with the aggregate outcomes of the comparator.

- Assess uncertainty: Use appropriate methods (e.g., bootstrapping) to account for uncertainty in the weighting process.

MAIC effectively reduces observed cross-trial differences but cannot adjust for unobserved or unreported differences between trial populations [7].

Validity Assessment of Indirect Comparisons

Empirical Evidence on Validity

Empirical studies have investigated the validity of ITCs by comparing their results with direct evidence from head-to-head trials. A landmark study from 2003 examined 44 comparisons from 28 systematic reviews where both direct and indirect evidence were available [6].

Table 3: Validity Assessment of Indirect Comparisons

| Validity Metric | Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical agreement | Significant discrepancy (P<0.05) in 3 of 44 comparisons [6] | Indirect comparisons usually agree with direct evidence but not always |

| Direction of discrepancy | No consistent pattern of overestimation or underestimation [6] | Discrepancies are unpredictable and may go in either direction |

| Clinical importance | Most discrepancies were not clinically important, but some exceptions existed [6] | Clinical judgment is needed beyond statistical significance |

| Acceptance by HTA bodies | Varies by agency; some accept ITCs with caveats while others remain hesitant [1] | Uncertainty in similarity assessment affects acceptability |

Assessment of Key Assumptions

Rigorous assessment of the underlying assumptions is critical for evaluating the validity of an ITC:

Similarity Assessment: Compare patient characteristics (age, disease severity, comorbidities), trial methodologies (design, blinding, duration), and outcome definitions across the trials involved in the indirect comparison [3] [4]. Statistical methods like meta-regression can explore the impact of study-level covariates on treatment effects.

Homogeneity Assessment: Evaluate statistical heterogeneity within each direct comparison using I² statistics, Cochran's Q test, or visual inspection of forest plots [5] [4]. Qualitative assessment of clinical and methodological diversity complements statistical measures.

Consistency Assessment: When both direct and indirect evidence exist, use statistical tests for inconsistency (e.g., node-splitting) or compare direct and indirect estimates through sensitivity analyses [3] [4]. Significant inconsistency requires investigation of potential effect modifiers or methodological biases.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Indirect Comparisons

Table 4: Essential Methodological Tools for Indirect Treatment Comparisons

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (gemtc, pcnetmeta), WinBUGS/OpenBUGS, Stata | Implement various ITC methods including NMA, MAIC, and Bucher method | Bayesian frameworks preferred when source data are sparse [2] |

| Data Requirements | Individual Patient Data (IPD), Aggregate Data | IPD enables more sophisticated adjustment methods like MAIC | MAIC and STC require IPD for at least one treatment [2] [7] |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Cochrane Risk of Bias, PRISMA-NMA | Assess methodological quality and reporting of primary studies and ITCs | Critical for evaluating validity of underlying evidence [4] |

| Assumption Verification Methods | Meta-regression, Subgroup analysis, Sensitivity analysis | Investigate heterogeneity, consistency, and similarity assumptions | Should be pre-specified in analysis plan [3] [4] |

Indirect Treatment Comparisons using the common comparator paradigm represent a sophisticated methodological approach that enables comparative effectiveness research when direct evidence is unavailable or insufficient. The validity of these comparisons hinges on carefully assessing the assumptions of similarity, homogeneity, and consistency. While various ITC methods are available—from the relatively simple Bucher method to more complex approaches like MAIC and NMA—method selection should be guided by the available data, research question, and need to adjust for cross-trial differences.

As therapeutic landscapes evolve rapidly, with new interventions emerging particularly in oncology and rare diseases, ITCs will continue to play a crucial role in informing healthcare decision-making. However, researchers must maintain rigorous standards in conducting and reporting ITCs, transparently communicating uncertainties and limitations to ensure appropriate interpretation by clinicians, policymakers, and patients.

In health technology assessment (HTA), decision-makers frequently need to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of treatments for which direct head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are unavailable, unethical, or unfeasible [2]. Indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs) provide a methodological framework to address this evidence gap through quantitative techniques that enable comparative estimates between interventions that have not been studied directly against each other [3] [8]. The core distinction in ITC methodology lies between anchored and unanchored approaches, a classification dependent on the presence or absence of a common comparator that connects the evidence network [9] [10].

The validity and acceptance of these methods by HTA bodies worldwide hinge on their underlying assumptions and ability to minimize bias [8] [11]. As the European Union prepares to implement its Joint Clinical Assessment (JCA) procedure in 2025, understanding the critical distinctions between these approaches and their standing with HTA agencies becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals [10] [12]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of anchored versus unanchored ITCs, detailing their methodologies, applications, and relative positions in HTA decision-making.

Core Conceptual Distinctions

Foundational Principles and Network Structures

Anchored and unanchored ITCs differ fundamentally in their evidence network structures and the analytical assumptions they require. The following diagram illustrates the key differences in their evidence networks and analytical flow.

Anchored ITCs require a connected network of evidence where treatments are linked through a common comparator (e.g., placebo or a standard active treatment) [9] [10]. This common comparator serves as an "anchor" that preserves the randomization within each original trial, thereby minimizing bias in the resulting indirect treatment effect estimates [9]. The anchored approach encompasses methods such as network meta-analysis (NMA), the Bucher method, matching-adjusted indirect comparisons (MAIC), and simulated treatment comparisons (STC) when a common comparator is present [3] [10].

Unanchored ITCs, in contrast, are employed when the evidence network is disconnected and lacks a common comparator, typically involving single-arm studies or comparisons where the treatments share no mutual reference point [9] [10]. This approach relies on comparing absolute treatment effects across studies and requires much stronger assumptions, particularly that there are no unmeasured confounders or effect modifiers influencing the outcomes [9]. Unanchored comparisons are generally considered more susceptible to bias and receive greater scrutiny from HTA bodies [10] [13].

Comparative Characteristics and HTA Perspectives

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, methodological requirements, and HTA preferences for anchored versus unanchored ITC approaches.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and HTA Perspectives of Anchored vs. Unanchored ITCs

| Characteristic | Anchored ITCs | Unanchored ITCs |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence Network | Connected network with common comparator | Disconnected network without common comparator |

| Foundation | Preserves within-trial randomization | Relies on comparison of absolute effects |

| Key Assumptions | Constancy of relative treatment effects | No unmeasured confounders or effect modifiers |

| Common Methods | NMA, Bucher, MAIC, STC (anchored) | MAIC (unanchored), STC (unanchored) |

| Data Requirements | Aggregate data or IPD from at least one trial with common comparator | Typically IPD for one treatment and aggregate for another |

| Strength of Evidence | Higher - respects randomization | Lower - vulnerable to confounding |

| HTA Acceptance | Generally preferred and accepted [10] [8] | Limited acceptance, require strong justification [9] [10] |

| Typical Applications | Connected networks of RCTs | Single-arm trials, disconnected evidence |

The fundamental distinction in HTA acceptance stems from the preservation of randomization in anchored approaches versus the inherent risk of confounding in unanchored methods [9] [10]. HTA bodies consistently express preference for anchored methods when feasible, as they maintain the integrity of randomization and provide more reliable estimates of relative treatment effects [8]. Unanchored approaches are typically reserved for situations where anchored comparisons are impossible, such as when single-arm trials constitute the only available evidence, often in oncology or rare diseases [2] [10].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Various statistical methods have been developed to implement both anchored and unanchored ITCs, each with distinct requirements, strengths, and limitations. The following table provides a comparative overview of the primary ITC techniques used in practice.

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Indirect Treatment Comparisons

| ITC Method | Class | Data Requirements | Key Assumptions | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bucher Method [3] [2] | Anchored | Aggregate data | Constancy of relative effects (homogeneity, similarity) | Simple implementation for pairwise comparisons via common comparator | Limited to comparisons with common comparator; cannot incorporate multi-arm trials |

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) [3] [2] | Anchored | Aggregate data | Constancy of relative effects (homogeneity, similarity, consistency) | Simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions; can incorporate both direct and indirect evidence | Complex with challenging-to-verify assumptions; requires connected network |

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) [3] [9] | Anchored or Unanchored | IPD for index treatment, aggregate for comparator | Constancy of relative or absolute effects | Adjusts for population imbalances via propensity score weighting | Limited to pairwise comparisons; cannot adjust for unobserved confounding |

| Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC) [3] [9] | Anchored or Unanchored | IPD for index treatment, aggregate for comparator | Constancy of relative or absolute effects | Regression-based adjustment for population differences | Limited to pairwise comparisons; requires correct model specification |

| Network Meta-Regression (NMR) [3] [2] | Anchored | Aggregate data (IPD optional) | Conditional constancy of relative effects with shared effect modifiers | Explores impact of study-level covariates on treatment effects | Low power with aggregate data; ecological bias risk |

According to a recent systematic literature review, NMA is the most frequently described ITC technique (79.5% of included articles), followed by MAIC (30.1%), network meta-regression (24.7%), the Bucher method (23.3%), and STC (21.9%) [2]. The appropriate selection among these methods depends on the evidence network structure, availability of individual patient data (IPD), magnitude of between-trial heterogeneity, and the specific research question [3] [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) Protocol

MAIC is a population-adjusted method that requires IPD for at least one treatment and aggregate data for the comparator [9] [13]. The experimental protocol involves the following key steps:

Effect Modifier Identification: Prior to analysis, identify and justify potential effect modifiers (patient characteristics that influence treatment effect) based on clinical knowledge and systematic literature review [9]. This pre-specification is critical for HTA acceptance [12].

Propensity Score Estimation: Using the IPD, fit a logistic regression model to estimate the probability (propensity) that a patient belongs to the index trial versus the comparator trial, based on the identified effect modifiers [9].

Weight Calculation: Calculate weights for each patient in the IPD as the inverse of their propensity score, effectively creating a "pseudo-population" where the distribution of effect matches the comparator trial [9].

Outcome Analysis: Fit a weighted outcome model to the IPD and compare the adjusted outcomes with the aggregate outcomes from the comparator trial [9]. For anchored MAIC, this comparison is made relative to the common comparator; for unanchored MAIC, absolute outcomes are directly compared [9].

Uncertainty Estimation: Use bootstrapping or robust variance estimation to account for the weighting uncertainty in confidence intervals [9]. HTA guidelines emphasize comprehensive sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of weighting and model assumptions [12].

A methodological review of 133 publications revealed inconsistent reporting of MAIC methodologies and potential publication bias, with 56% of analyses reporting statistically significant benefits for the treatment evaluated with IPD [13]. This highlights the importance of transparent reporting and rigorous methodology.

Network Meta-Analysis Protocol

NMA simultaneously compares multiple treatments by combining direct and indirect evidence across a connected network of trials [3] [2]. The experimental protocol involves:

Systematic Literature Review: Conduct a comprehensive search to identify all relevant RCTs for the treatments and conditions of interest, following PRISMA guidelines [2].

Evidence Network Mapping: Graphically represent the treatment network, noting all direct comparisons and identifying potential disconnected components [3].

Assessment of Transitivity: Evaluate the clinical and methodological similarity of trials included in the network, ensuring that patient populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study designs are sufficiently homogeneous [3].

Statistical Analysis: Implement either frequentist or Bayesian statistical models to synthesize evidence [3] [12]. Bayesian approaches are particularly useful when data are sparse, as they allow incorporation of prior distributions [12].

Consistency Evaluation: Assess the statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence where available, using node-splitting or other diagnostic approaches [3].

Uncertainty and Heterogeneity: Quantify heterogeneity and inconsistency in the network, and conduct sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of findings [12].

The 2024 EU HTA methodological guidelines emphasize pre-specification of statistical models, comprehensive sensitivity analyses, and transparent reporting of all methodological choices [12].

Global HTA Perspectives on ITC Methods

Health technology assessment bodies worldwide have established preferences regarding ITC methodologies, with clear distinctions in their acceptance of anchored versus unanchored approaches. The following diagram illustrates the key criteria that HTA bodies consider when evaluating ITC evidence.

A targeted review of worldwide ITC guidelines revealed that most jurisdictions favor population-adjusted or anchored ITC techniques over naïve comparisons or unanchored approaches [8]. The preference for anchored methods stems from their preservation of randomization and more testable assumptions compared to unanchored approaches, which rely on stronger, often untestable assumptions about the absence of unmeasured confounding [9] [8].

The European Union's upcoming JCA process emphasizes methodological flexibility without endorsing specific approaches, but clearly stresses the importance of pre-specification, comprehensive sensitivity analyses, and transparency in all ITC submissions [12]. Similarly, other HTA bodies acknowledge the utility of ITCs when direct evidence is lacking but maintain stringent criteria for their acceptance [8].

Acceptance Criteria for Different ITC Scenarios

Table 3: HTA Acceptance Criteria for Different ITC Scenarios

| Scenario | Recommended Methods | HTA Acceptance Level | Key Requirements for Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connected network of RCTs | NMA, Bucher method | High [2] [8] | Assessment of transitivity, homogeneity, consistency |

| Connected network with population heterogeneity | MAIC, STC, NMR | Moderate to High [3] [9] | IPD availability, justification of effect modifiers, adequate population overlap |

| Disconnected network with single-arm studies | Unanchored MAIC, Unanchored STC | Low to Moderate [9] [10] | Strong justification for effect modifiers, comprehensive sensitivity analyses, acknowledgment of limitations |

| Rare diseases with limited evidence | Population-adjusted methods | Case-by-case [2] [12] | Transparency about uncertainty, clinical rationale for assumptions |

For unanchored comparisons, HTA acceptance remains limited due to the fundamental methodological challenges. The NICE Decision Support Unit emphasizes that unanchored comparisons "make much stronger assumptions, which are widely regarded as infeasible" [9]. Similarly, industry assessments note that unanchored approaches "are not recommended by most HTA agencies and should only be used when anchored methods are unfeasible" [10].

A review of MAIC applications found that studies frequently report statistically significant benefits for the treatment evaluated with IPD, with only one analysis significantly favoring the treatment evaluated with aggregate data [13]. This pattern suggests potential reporting bias and underscores the need for cautious interpretation of results from population-adjusted methods, particularly in unanchored scenarios [13] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Components

The following table details key methodological components and their functions in conducting robust ITCs, representing the essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 4: Essential Methodological Components for Indirect Treatment Comparisons

| Component | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Patient Data (IPD) | Enables patient-level adjustment for population imbalances | Required for MAIC, STC; allows examination of effect modifiers and prognostic factors [9] [13] |

| Aggregate Data | Provides comparison outcomes and population characteristics | Typically available from published literature; used in all ITC types [3] |

| Effect Modifier Identification Framework | Systematically identifies patient characteristics that influence treatment effects | Critical for population-adjusted methods; should be pre-specified and clinically justified [9] [12] |

| Propensity Score Models | Estimates probability of trial membership based on baseline characteristics | Foundation of MAIC; used to weight patients to achieve balance across studies [9] |

| Bayesian Statistical Models | Incorporates prior distributions for parameters | Particularly valuable when data are sparse; allows incorporation of external evidence [3] [12] |

| Frequentist Statistical Models | Provides traditional inference framework | Widely used in NMA; relies solely on current data without incorporating prior distributions [3] |

| Consistency Assessment Tools | Evaluates agreement between direct and indirect evidence | Includes node-splitting, design-by-treatment interaction tests; essential for NMA validation [3] |

| Sensitivity Analysis Framework | Tests robustness of results to methodological choices | Critical for HTA acceptance; should explore impact of model specifications, priors, and inclusion criteria [12] |

The critical distinction between anchored and unanchored ITCs lies in the presence of a common comparator and the consequent strength of methodological assumptions. Anchored methods preserve the integrity of within-trial randomization and consequently receive higher acceptance from HTA bodies worldwide [10] [8]. Unanchored methods, while necessary in specific circumstances such as single-arm trials or disconnected evidence networks, require stronger assumptions and consequently face greater scrutiny and limited acceptance [9] [13].

For researchers and drug development professionals, selection between these approaches should be guided primarily by the available evidence network structure, with anchored methods preferred whenever possible [3] [2]. When population-adjusted methods like MAIC or STC are employed, comprehensive pre-specification of effect modifiers, transparent reporting, and rigorous sensitivity analyses are essential for HTA acceptance [12] [13]. As the European Union implements its new JCA process in 2025, adherence to methodological guidelines and early engagement with HTA requirements will be crucial for successful market access applications [10] [12].

In health technology assessment (HTA) and drug development, head-to-head randomized clinical trial data for all relevant treatments are often unavailable. Indirect Treatment Comparisons (ITCs) are methodologies used to compare the effects of different treatments through a common comparator, such as placebo or a standard care treatment. The validity of any ITC hinges on two fundamental assumptions: the constancy of relative effects and similarity [3].

The constancy of relative effects, also referred to as homogeneity or similarity, assumes that the relative effect of a treatment compared to a common comparator is constant across different study populations. When this assumption holds, simple indirect comparison methods like the Bucher method can provide valid results. Similarity extends beyond just the treatment effects and encompasses the idea that the studies being compared are sufficiently alike in their key characteristics, such as patient populations, interventions, outcomes, and study designs (the PICO framework). Violations of these assumptions can introduce significant bias into the comparison, leading to incorrect conclusions about the relative efficacy and safety of treatments [3].

This guide objectively compares the performance of different ITC methodologies, detailing their experimental protocols, inherent assumptions, and performance data to assist researchers in selecting and validating the most appropriate approach for their research.

Conceptual Framework and Key Terminology

Foundational Concepts in ITC

Indirect comparisons form a connected network of evidence, allowing for the estimation of relative treatment effects between interventions that have never been directly compared in a randomized trial. The simplest form is a pairwise indirect comparison via the Bucher method, which connects two treatments (e.g., B and C) through a common comparator A [3]. More complex Network Meta-Analyses (NMA) allow for the simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments [3]. Table 1 provides a glossary of essential terms used in the field.

Table 1: Key Terminology in Indirect Treatment Comparisons

| Term | Definition | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Constancy of Relative Effects [3] | The assumption that relative treatment effects are constant across different study populations. Also referred to as homogeneity or similarity. | Fundamental for unadjusted ITCs. Violation introduces bias. |

| Conditional Constancy of Relative Effects [14] | A relaxed constancy assumption that holds true only after adjusting for all relevant effect modifiers. | Core assumption for anchored population-adjusted methods. |

| Similarity [3] | The degree to which studies in a comparison are alike in their PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) elements. | Assessed both clinically and methodologically prior to analysis. |

| Effect Modifier [14] | A patient or study characteristic that influences the relative effect of a treatment. | Imbalance in these between studies violates the constancy assumption. |

| Anchored Comparison [14] | An indirect comparison that utilizes a common comparator shared between studies. | Relaxes the data requirements compared to unanchored comparisons. |

| Unanchored Comparison [14] | A comparison made in the absence of a common comparator, often involving single-arm studies. | Requires the much stronger assumption of conditional constancy of absolute effects. |

The Role of Assumptions in Different ITC Frameworks

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core assumptions, data availability, and the appropriate selection of ITC methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of ITC Methodologies

The landscape of ITC methods has evolved to handle scenarios where the fundamental constancy assumption is violated. Population-Adjusted Indirect Comparisons (PAIC) leverage individual patient data (IPD) from at least one study to adjust for imbalances in effect modifiers [14]. The most common PAIC methods are Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC), Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC), and Multilevel Network Meta-Regression (ML-NMR) [15]. The experimental workflow for implementing these methods is detailed below.

Performance Data from Simulation Studies

Simulation studies are critical for understanding the performance of different PAIC methods under controlled conditions, especially when assumptions are not fully met. A key simulation study assessed the performance of MAIC, STC, and ML-NMR across various scenarios [15]. The results are summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Population Adjustment Methods in Simulation Studies [15]

| Simulation Scenario | MAIC Performance | STC Performance | ML-NMR Performance | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Assumptions Met | Increased bias compared to standard ITC; poor performance. | Bias eliminated when assumptions were met. | Bias eliminated when assumptions were met; robust. | ML-NMR and STC are preferred when their specific assumptions are justified. |

| Missing Effect Modifier | Significant bias introduced. | Significant bias introduced. | Significant bias introduced. | Careful selection of all effect modifiers prior to analysis is essential for all methods. |

| Poor Population Overlap | Performance deteriorated severely; high variance due to low Effective Sample Size (ESS). | Performance impacted by extrapolation. | More robust to varying degrees of between-study overlap. | Check covariate distributions and ESS (for MAIC) before analysis. |

| Larger Treatment Networks | Not designed for larger networks; limited application. | Not designed for larger networks; limited application. | Effectively handles networks with multiple treatments and studies. | ML-NMR is the most flexible method for complex evidence networks. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successfully conducting a robust indirect comparison requires more than just statistical software. The following table details essential "research reagents" and their functions in the experimental process of an ITC.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Indirect Comparison Research

| Research Reagent | Function in ITC Analysis |

|---|---|

| Individual Patient Data (IPD) | The raw data from a clinical trial, allowing for patient-level analysis, validation of effect modifiers, and application of PAIC methods like MAIC and STC [14]. |

| Aggregate Data (AgD) | Published summary data (e.g., mean outcomes, covariate summaries) from other studies used to build the evidence network. The quality and completeness of AgD reporting are critical [14]. |

| Covariate Selection Framework | A pre-specified, principled approach (informed by clinical experts and prior evidence) for identifying effect modifiers and prognostic variables to adjust for, crucial for minimizing bias and avoiding "gaming" [14]. |

| Effective Sample Size (ESS) | A metric calculated from the weights in a MAIC analysis. A large reduction in ESS indicates poor population overlap and may lead to an unstable and imprecise comparison [14]. |

| Non-Inferiority Margin | A pre-defined threshold used in formal equivalence testing, which can be integrated with ITCs in a Bayesian framework to provide probabilistic evidence for clinical similarity in cost-comparison analyses [16]. |

The Evolving Landscape of Global HTA Guidelines for ITC Acceptance

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) bodies worldwide face a persistent challenge: making informed recommendations about new health interventions often without direct head-to-head randomized clinical trial data against standard-of-care treatments [3]. In this evidence gap, Indirect Treatment Comparison (ITC) methodologies have become indispensable tools for generating comparative evidence. ITCs encompass statistical techniques that allow comparison of treatments that have not been directly studied in the same clinical trial, by using a common comparator or network of evidence [3] [17].

The global acceptance of ITC methods by HTA agencies remains varied, with overall acceptance rates generally low, creating a complex landscape for drug developers and researchers [17]. A comprehensive analysis of HTA evaluation reports between 2018 and 2021 found that only 22% presented an ITC, with an overall acceptance rate of just 30% [17]. This underscores the critical importance of understanding the methodological requirements and preferences of different HTA bodies. With the impending implementation of the EU HTA Regulation (EU 2021/2282) in 2025, which will standardize assessments across Europe, understanding this evolving landscape becomes even more crucial for successful HTA submissions [12].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of ITC acceptance across major HTA agencies, detailing methodological preferences, quantitative acceptance data, and strategic frameworks for selecting and implementing ITCs that meet rigorous HTA standards.

Comparative Analysis of HTA Agency Acceptance of ITC Methods

Quantitative Acceptance Rates Across Major HTA Markets

Comprehensive analysis of HTA evaluations reveals significant variation in ITC acceptance across different jurisdictions. The table below summarizes acceptance rates and methodological preferences for key HTA agencies based on recent publications (2018-2021) [17].

Table 1: ITC Acceptance Rates and Methodological Preferences by HTA Agency

| HTA Agency/Country | Reports with ITC (%) | ITC Acceptance Rate (%) | Commonly Accepted Methods | Primary Criticisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NICE (England) | 51% | 47% | NMA, Bucher, MAIC | Heterogeneity, statistical methods |

| G-BA/IQWiG (Germany) | 24% | 24% | NMA, Bucher | Data limitations, heterogeneity |

| AIFA (Italy) | 17% | 22% | NMA, MAIC | Lack of data, methodological concerns |

| AEMPS (Spain) | 11% | 19% | NMA, Bucher | Heterogeneity, statistical methods |

| HAS (France) | 6% | 0% | Limited acceptance | Data limitations, methodological concerns |

The variation in acceptance rates reflects fundamental differences in methodological stringency, evidentiary standards, and regulatory philosophies across HTA agencies. England's NICE demonstrates the highest acceptance rate (47%), while France's HAS did not accept any ITCs in the studied period [17]. The most common criticisms cited by HTA agencies relate to data limitations (48%), heterogeneity between studies (43%), and concerns about statistical methods used (41%) [17].

The choice of ITC methodology significantly influences its likelihood of acceptance by HTA agencies. The table below illustrates the usage and acceptance rates of different ITC techniques based on a systematic literature review and analysis of HTA submissions [17] [2].

Table 2: ITC Method Usage and Acceptance Patterns

| ITC Method | Description | Frequency of Use | Acceptance Rate | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) | Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments using direct & indirect evidence | 79.5% of ITC articles [2] | 39% [17] | Preferred for connected networks; consistency assumptions critical |

| Bucher Method | Adjusted indirect comparison for simple networks via common comparator | 23.3% of ITC articles [2] | 43% [17] | Suitable for pairwise comparisons with common comparator |

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) | Reweighting IPD to match AgD baseline characteristics | 30.1% of ITC articles [2] | 33% [17] | Requires IPD from at least one trial; addresses population differences |

| Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC) | Predicts outcomes using regression models based on IPD | 21.9% of ITC articles [2] | Limited data | Applied with single-arm studies; strong assumptions required |

| Network Meta-Regression (NMR) | Incorporates trial-level covariates to adjust for heterogeneity | 24.7% of ITC articles [2] | Limited data | Addresses cross-trial heterogeneity; requires multiple studies |

Recent trends indicate increased use of population-adjusted methods like MAIC, particularly in submissions involving single-arm trials, which are increasingly common in oncology and rare diseases [2]. Among recent articles (published from 2020 onwards), 69.2% describe population-adjusted methods, notably MAIC [2].

Methodological Framework for ITC Selection and Application

Strategic Selection of ITC Methods

The strategic selection of an appropriate ITC method depends on several factors, including the connectedness of the evidence network, availability of individual patient data (IPD), and the presence of heterogeneity between studies [3] [2]. The following decision framework illustrates the methodological selection process:

This structured approach to method selection emphasizes the importance of evidence network structure and data availability in determining the most appropriate ITC technique. HTA guidelines consistently emphasize that the choice between methods should be justified based on the specific scope and context of the analysis rather than defaulting to any single approach [12].

The EU HTA Regulation 2025: New Methodological Standards

The impending EU HTA Regulation (2021/2282), fully effective from January 2025, establishes new methodological standards for ITCs in Joint Clinical Assessments (JCAs) [12]. The regulation specifies several key methodological requirements:

- Pre-specification of analyses: Statistical analyses must be determined and documented before conducting any analysis to prevent selective reporting and ensure scientific rigor [12]

- Comprehensive uncertainty assessment: Sensitivity analyses must explore the impact of missing data and methodological assumptions [12]

- Transparency in methodology: Clear documentation of models and methods, avoiding "cherry-picking" of data [12]

- Accounting for effect modifiers: Identification and adjustment for all relevant baseline characteristics that could influence treatment effects [12]

The EU HTA guidance acknowledges both frequentist and Bayesian approaches without clear preference, noting that Bayesian methods are particularly useful in situations with sparse data due to their ability to incorporate prior information [12].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks for ITC

Methodological Protocols for Robust ITC

Implementing methodologically robust ITCs requires strict adherence to validated protocols. Based on HTA agency guidelines, the following experimental protocols are recommended:

Network Meta-Analysis Protocol:

- Systematic Literature Review: Comprehensive search across multiple databases following PRISMA guidelines to identify all relevant RCTs [2]

- Network Feasibility Assessment: Evaluation of transitivity and similarity assumptions across studies, including study designs, patient characteristics, treatments, and outcomes [3]

- Statistical Model Selection: Choice between fixed-effect and random-effects models based on heterogeneity assessment [3]

- Consistency Evaluation: Assessment of consistency between direct and indirect evidence using node-splitting or other appropriate methods [3]

- Uncertainty Quantification: Sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of findings to methodological assumptions [12]

Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison Protocol:

- IPD Preparation: Collection and validation of individual patient data from at least one trial [17]

- Effect Modifier Identification: Selection of baseline characteristics expected to modify treatment effect based on clinical knowledge [12]

- Propensity Score Estimation: Calculation of propensity scores based on the distribution of effect modifiers in IPD and aggregate data [17]

- Population Reweighting: Application of propensity score weights to match the IPD population to the aggregate data population [12]

- Outcome Comparison: Comparison of reweighted outcomes with the aggregate data using appropriate statistical methods [17]

Validation and Sensitivity Analysis Framework

HTA agencies emphasize the importance of comprehensive validation and sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of ITC findings:

- Goodness-of-Fit Assessment: Evaluation of model fit using deviance information criteria (DIC) for Bayesian models or Akaike information criterion (AIC) for frequentist models [3]

- Heterogeneity Exploration: Investigation of between-study heterogeneity using I² statistics or predictive intervals [3]

- Influence Analysis: Assessment of the impact of individual studies on overall treatment effect estimates [3]

- Scenario Analyses: Evaluation of results under different assumptions, such as alternative prior distributions in Bayesian analyses or different handling of multi-arm trials [12]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ITC Analysis

Successful implementation of ITCs requires specific methodological tools and approaches. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" - core methodological components essential for robust ITC analysis.

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for ITC Analysis

| Methodological Component | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Patient Data (IPD) | Enables population-adjusted methods like MAIC and STC; allows exploration of treatment-effect modifiers | Essential when significant heterogeneity exists between study populations; required for unanchored comparisons [12] [17] |

| Aggregate Data (AgD) | Foundation for standard ITC methods like NMA and Bucher; required from comparator studies | Standard input for connected network meta-analyses; sufficient when population similarity exists [12] |

| Propensity Score Weighting | Balcomes baseline characteristics between IPD and AgD populations by assigning weights to patients | Core component of MAIC; adjusts for population differences when comparing across studies [12] [17] |

| Bayesian Hierarchical Models | Provides framework for evidence synthesis with incorporation of prior knowledge; handles sparse data effectively | Preferred for complex networks with multi-arm trials; useful when incorporating real-world evidence [12] |

| Frequentist Fixed/Random Effects Models | Traditional statistical approach for evidence synthesis; widely understood and implemented | Standard choice for conventional NMA; preferred when prior information is limited or controversial [3] |

| Network Meta-Regression | Explores impact of study-level covariates on treatment effects; adjusts for cross-trial heterogeneity | Applied when effect modifiers are identified at study level; requires multiple studies for sufficient power [3] [17] |

The global landscape of ITC acceptance in HTA continues to evolve, with significant variations in methodological preferences and acceptance rates across different agencies. The forthcoming EU HTA Regulation (2025) represents a substantial shift toward standardization, while maintaining flexibility in methodological approach selection [12].

Successful navigation of this landscape requires:

- Strategic method selection based on evidence network structure and data availability

- Rigorous adherence to methodological protocols with comprehensive sensitivity analyses

- Early engagement with HTA bodies to align on methodological approach, particularly for novel ITC methods

- Transparent reporting of assumptions, limitations, and uncertainty in ITC findings

As HTA methodologies continue to advance, the development of more sophisticated ITC techniques and their increasing acceptance hold promise for more efficient and informative comparative effectiveness research, ultimately supporting better healthcare decision-making worldwide.

Why Common Comparators are Crucial for Minimizing Bias and Preserving Randomization

In clinical research, the choice of a common comparator is a fundamental aspect of trial design that directly impacts the validity, interpretability, and utility of study findings. Common comparators serve as a critical anchor, enabling fair and scientifically sound comparisons between interventions, especially when direct head-to-head evidence is absent. Their proper use preserves the integrity of randomization—the cornerstone of randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—by providing a baseline against which treatment effects can be measured without systematic bias. This guide explores the pivotal role of common comparators in minimizing bias, detailing the methodological frameworks for their application in both direct and indirect comparison analyses. Through explicit experimental protocols and data presentations, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to design more rigorous and unbiased clinical studies.

The Fundamental Role of Comparators in Clinical Research

A comparator (or control) is a benchmark or reference against which the effects of an investigational medical intervention are evaluated [18]. In clinical trials, this can be a placebo, an active drug representing the standard of care, a different dose of the study drug, or even no treatment [19] [18]. The use of a comparator is non-negotiable for establishing the relative efficacy and safety of a new treatment; without it, attributing observed effects solely to the intervention under investigation is impossible, as they could result from other factors such as the natural progression of the disease or patient expectations [18].

The selection of an appropriate comparator is deeply intertwined with the principle of randomization. Random allocation of participants to treatment or comparator groups is the most effective method for minimizing selection bias [20]. It works by eliminating systematic differences between comparison groups, ensuring that any differences in outcomes can be reliably attributed to the treatment effect rather than confounding variables, whether known or unknown [20]. The comparator group provides the essential reference point that allows this attributed effect to be quantified. Controversies in trial design often revolve around comparator choice, as this decision directly affects a trial's purpose, feasibility, fundability, and ultimate impact [19] [21].

Common Comparators as Anchors for Unbiased Indirect Comparisons

In an ideal world, all relevant treatment options would be compared directly in head-to-head randomized controlled trials. However, this is often impractical due to economic constraints, the dynamic nature of treatment landscapes, and the fact that drug registration in many markets historically required only demonstration of efficacy versus a placebo [22] [1] [8]. This evidence gap creates a critical need for methods to compare interventions that have never been directly studied against one another.

This is where the common comparator becomes indispensable. A common comparator enables Indirect Treatment Comparisons (ITCs), which are statistical techniques used to estimate the relative treatment effect of two interventions (e.g., Drug A and Drug B) by leveraging their direct comparisons against a shared anchor, or "common comparator" (e.g., Drug C or a placebo) [22] [1] [23].

- The Statistical Foundation: The most accepted method for ITC is the adjusted indirect comparison [22]. It preserves the original randomization of the constituent trials by comparing the relative treatment effects of each drug versus the common comparator. The difference between Drug A and Drug B is estimated by subtracting their respective effects versus the common comparator [22] [23].

- Contrast with Naïve Comparisons: It is crucial to distinguish adjusted indirect comparisons from "naïve direct comparisons," which simply compare the outcome of Drug A from one trial directly with the outcome of Drug B from another trial without any adjustment for the common comparator [22]. This naïve approach "breaks" the original randomization, is subject to significant confounding and bias from systematic differences between the trials (e.g., in patient populations or study design), and provides no more robust evidence than a comparison of observational studies [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical structure of an adjusted indirect comparison using a common comparator.

Experimental Protocols for Indirect Comparison Analysis

Conducting a valid and credible indirect comparison requires a rigorous, multi-step methodology. The following protocol, consistent with guidelines from international health technology assessment (HTA) agencies like NICE (UK) and CADTH (Canada), outlines the core process [22] [8].

Protocol 1: Conducting an Adjusted Indirect Comparison

Objective: To estimate the relative efficacy and/or safety of Intervention A versus Intervention B using a common comparator C.

Step 1: Define the Research Question and Eligibility Criteria Clearly specify the interventions (A, B, C), the patient population, and the outcomes of interest. Develop detailed eligibility criteria for the studies to be included (e.g., study design, treatment duration, outcome measures) [8] [23].

Step 2: Systematic Literature Review Conduct a comprehensive and reproducible search of scientific literature databases (e.g., MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central) to identify all relevant randomized controlled trials that compare A vs. C and B vs. C [23]. The search strategy, including keywords and filters, must be documented transparently.

Step 3: Study Selection and Data Extraction Screen search results against the eligibility criteria. From each included study, extract data on study characteristics, patient baseline characteristics, and outcome data for all treatment arms [23]. This is typically performed by at least two independent reviewers to minimize error and bias.

Step 4: Assess Similarity and Transitivity This is a critical qualitative step. Evaluate whether the trials for A vs. C and B vs. C are sufficiently similar in their key aspects (e.g., patient population, dosage of common comparator C, study definitions, and methods for measuring outcomes) to justify a fair comparison [22] [1] [8]. The validity of the ITC rests on this assumption of similarity (or transitivity).

Step 5: Perform Meta-Analysis (if required) If multiple trials exist for the same direct comparison (e.g., several A vs. C trials), a meta-analysis should be conducted to generate a single, precise estimate of the treatment effect for that comparison [23]. This can be done using software like Review Manager, applying either a fixed-effect or random-effects model depending on the presence of heterogeneity.

Step 6: Calculate the Adjusted Indirect Comparison

Apply the Bucher method [22] [23] to compute the indirect estimate. For a continuous outcome (e.g., change in FEV1), the calculation is:

D_IC = D_AC - D_BC, where D_AC is the mean difference between A and C, and D_BC is the mean difference between B and C.

The standard error is: SE_IC = sqrt( SE_AC^2 + SE_BC^2 ).

For a binary outcome (e.g., response rate), the comparison is done using relative risks (RR) or odds ratios (OR): RR_IC = RR_AC / RR_BC [22].

Step 7: Assess Inconsistency If a closed loop of evidence exists (i.e., there are direct comparisons for A vs. B, A vs. C, and B vs. C), statistically test for inconsistency between the direct and indirect estimates of the A vs. B effect. A significant difference may indicate a violation of the similarity assumption [23].

Case Study: Comparing Inhaled Corticosteroids in Asthma

A study by Kunitomi et al. (2015) provides a clear example of ITC in practice, comparing the efficacy of different inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for asthma where direct head-to-head evidence was limited [23].

Objective: To indirectly compare the change in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) for fluticasone propionate (FP) vs. budesonide (BUD), FP vs. beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP), and BUD vs. BDP.

Methodology:

- A systematic literature review identified 23 eligible RCTs.

- Two common comparators were used: Placebo (PLB) and an active drug, Mometasone (MOM).

- Meta-analyses were performed for each ICS against PLB and against MOM.

- Adjusted indirect comparisons were conducted using both PLB and MOM as the common anchor.

Results: The table below summarizes the key findings of the indirect comparisons for the change in FEV1.

Table 1: Indirect Comparison Results for Inhaled Corticosteroids (Change in FEV1) [23]

| Comparison | Common Comparator | Mean Difference (L) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| FP vs. BUD | Placebo | 0.03 | (-0.07, 0.13) |

| FP vs. BUD | Mometasone | 0.04 | (-0.08, 0.16) |

| FP vs. BDP | Placebo | 0.08 | (-0.03, 0.19) |

| FP vs. BDP | Mometasone | 0.07 | (-0.06, 0.20) |

| BUD vs. BDP | Placebo | 0.05 | (-0.06, 0.16) |

| BUD vs. BDP | Mometasone | 0.03 | (-0.10, 0.16) |

Interpretation: The results demonstrated no statistically significant differences in efficacy between the various ICS, as all confidence intervals crossed zero. Crucially, the choice of common comparator (PLB or MOM) had no significant impact on the conclusions, as the point estimates and confidence intervals were very similar for both methods. This strengthens the credibility of the findings by showing robustness to the choice of a valid common comparator [23].

A Researcher's Toolkit for Comparator-Based Studies

Selecting and applying the right tools and methodologies is essential for conducting unbiased comparisons. The following table details key conceptual "reagents" and their functions in this process.

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Comparator-Based Research

| Tool / Concept | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Indirect Comparison [22] | Provides a statistically valid estimate of the relative effect of two treatments via a common comparator. | Preserves randomization from source trials. Preferred over naïve comparisons by HTA bodies. |

| Common Comparator [22] [1] | Serves as the anchor or link that enables indirect comparisons. | Can be a placebo, standard of care, or an active drug. Must be identical or very similar in all trials used. |

| Assumption of Similarity (Transitivity) [1] [8] | The foundational assumption that the trials being linked are sufficiently similar to permit a fair comparison. | Requires assessment of patient populations, study designs, dosages, and outcome definitions. Violations can invalidate the analysis. |

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) [8] | A sophisticated extension of ITC that incorporates all available direct and indirect evidence into a single, coherent analysis for multiple treatments. | Reduces uncertainty but requires complex statistical models (e.g., Bayesian frameworks) and strong assumptions. |

| Pragmatic Model for Comparator Selection [19] [21] | A decision-making framework for selecting the optimal comparator for a randomized controlled trial. | Emphasizes that the primary purpose of the trial is the most important factor in comparator choice, balancing attributes like acceptability, feasibility, and relevance. |

Visualization of Comparator Selection and Research Workflow

The process of selecting a comparator and designing a trial or evidence synthesis project is strategic. The following workflow, adapted from the NIH expert panel's Pragmatic Model, outlines the key decision points [19] [21].

The strategic use of common comparators is a pillar of unbiased clinical research. They are not merely passive control groups but active methodological tools that extend the power of randomization beyond single trials, enabling scientifically defensible comparisons in the absence of direct evidence. As the therapeutic landscape grows increasingly complex, mastery of indirect comparison methods and the principled selection of comparators—guided by frameworks such as the Pragmatic Model—will be indispensable for researchers, clinicians, and health policy makers. By rigorously applying these principles, the scientific community can ensure that decisions about the relative value of medical interventions are based on the most valid and least biased evidence possible.

A Practical Guide to ITC Methodologies: From Bucher to Bayesian and Population Adjustment

In the field of health technology assessment (HTA) and drug development, Indirect Treatment Comparisons (ITCs) have become indispensable statistical tools for evaluating the relative efficacy and safety of interventions when head-to-head randomized clinical trial (RCT) data are unavailable or infeasible [3]. The fundamental challenge facing researchers and drug development professionals lies in selecting the most appropriate ITC method from a growing arsenal of techniques, each with specific assumptions, data requirements, and limitations. This guide provides a structured decision framework based on evidence structure to navigate this complex methodological landscape, emphasizing the critical assessment of validity through the lens of common comparators research.

The necessity for ITCs arises from practical realities in global drug development: comparing a new treatment against all relevant market alternatives in head-to-head trials is often statistically impractical, economically unviable, or ethically constrained, particularly in oncology and rare diseases [24]. Furthermore, standard comparators vary significantly across jurisdictions, making single-trial comparisons insufficient for global market access [1]. ITCs address this evidence gap by enabling comparative effectiveness research through statistical linking of different studies, with the common comparator serving as the anchor that facilitates this indirect evidence synthesis [1].

Fundamental ITC Methodology and Classifications

Core Principles and Terminology

ITCs encompass a broad range of methods with inconsistent terminologies across the literature [3]. At their core, all ITCs aim to provide estimates of relative treatment effects between interventions that have not been directly compared in RCTs, using a common comparator as the statistical bridge. This common comparator (often a standard of care, placebo, or active control) enables the transitive linking of evidence across separate studies [1].

The validity of any ITC depends on satisfying fundamental assumptions that vary by method class. The constancy of relative effects assumption requires that treatment effects remain stable across the studies being compared, encompassing homogeneity (similar trial characteristics), similarity (comparable patient populations and trial designs), and consistency (coherence between direct and indirect evidence where available) [3]. When these assumptions are violated, methods based on conditional constancy may be employed, which incorporate effect modifiers through statistical adjustment [3].

Classification of ITC Methods

ITC methods can be categorized into four primary classes based on their underlying assumptions and the number of comparisons involved [3]:

- Bucher Method: Also known as adjusted or standard ITC, this approach facilitates pairwise comparisons through a common comparator using frequentist framework.

- Network Meta-Analysis (NMA): Extends the Bucher method to multiple interventions simultaneously, available in both frequentist and Bayesian frameworks.

- Population-Adjusted Indirect Comparisons (PAIC): Encompasses techniques that adjust for population imbalances across studies when individual patient data (IPD) are available.

- Naïve ITC: Refers to unadjusted comparisons that do not account for differences in study populations or characteristics.

The following table summarizes the key ITC methods, their applications, and fundamental requirements:

Table 1: Classification of Indirect Treatment Comparison Methods

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Evidence Structure Required | Data Requirements | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Methods | Bucher ITC [3] | Two interventions connected via common comparator | Aggregate data (AD) | Constancy of relative effects |

| Naïve ITC [3] | Interventions with no common comparator | AD | None (highly prone to bias) | |

| Multiple Treatment Comparisons | Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) [3] | Connected network of multiple interventions | Primarily AD | Homogeneity, similarity, consistency |

| Indirect NMA [3] | Multiple interventions with only indirect connections | AD | Homogeneity, similarity | |

| Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC) [3] | Network with both direct and indirect evidence | AD | Homogeneity, similarity, consistency | |

| Population-Adjusted Methods | Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) [3] | Pairwise comparisons with population imbalance | IPD for one trial, AD for another | Constancy of relative or absolute effects |

| Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC) [3] | Pairwise comparisons with population imbalance | IPD for one trial, AD for another | Constancy of relative or absolute effects | |

| Effect Modifier Adjustment | Network Meta-Regression (NMR) [3] | Connected network with effect modifiers | AD with study-level covariates | Conditional constancy with shared effect modifier |

| Multi-Level NMA (ML-NMR) [3] | Connected network with effect modifiers | IPD for some trials, AD for others | Conditional constancy with shared effect modifier |

Decision Framework for ITC Method Selection

Selecting the appropriate ITC method requires systematic evaluation of the available evidence structure, data resources, and clinical context. The following decision pathway provides a visual representation of the key considerations in method selection:

Decision Pathway for Selecting ITC Methods

This decision framework emphasizes that method selection depends primarily on three factors: the connectedness of the evidence network, the comparability of patient populations across studies, and the availability of data for adjustment. The pathway systematically guides researchers through these considerations to arrive at methodologically appropriate options.

Evidence Structure Assessment

The initial evidence assessment involves mapping all available comparative evidence to identify potential connecting pathways between the target interventions. This process includes:

- Systematic Literature Review: Comprehensive identification of all relevant RCTs for the interventions of interest and potential common comparators [3].

- Evidence Network Mapping: Visual representation of treatment comparisons as a network where nodes represent interventions and edges represent direct comparative evidence [3].

- Feasibility Evaluation: Assessment of whether the available evidence network supports connected indirect comparisons or requires more advanced adjustment methods.

When the evidence structure reveals a connected network with multiple interventions, NMA approaches are typically preferred as they enable simultaneous comparison of all interventions while borrowing strength from the entire network [3]. For simple pairwise comparisons through a common comparator, the Bucher method provides a straightforward approach, though its validity depends heavily on population similarity [3].

Data Requirements and Method Capabilities

Different ITC methods have varying data requirements and capabilities for addressing methodological challenges. The choice between them often depends on the availability of individual patient data (IPD) and the presence of effect modifiers:

Table 2: Data Requirements and Applications of Advanced ITC Methods

| Method | Data Requirements | Analytical Framework | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) [3] | IPD for index treatment, AD for comparator | Frequentist, often with propensity score weighting | Adjusting for population imbalances in pairwise comparisons; single-arm studies in rare diseases | Limited to pairwise comparisons; requires adequate IPD quality and sample overlap |

| Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC) [3] | IPD for index treatment, AD for comparator | Bayesian, often with outcome regression models | Addressing cross-study heterogeneity; unanchored comparisons | Limited to pairwise comparisons; model specification challenges |

| Network Meta-Regression (NMR) [3] | AD with study-level covariates | Frequentist or Bayesian | Exploring impact of study-level covariates on treatment effects; connected networks with effect modifiers | Cannot adjust for patient-level effect modifiers; not suitable for multi-arm trials |

| Multi-Level NMA (ML-NMR) [3] | IPD for some trials, AD for others | Bayesian with hierarchical models | Complex networks with both IPD and AD; patient-level effect modifier adjustment | Computational complexity; requires substantial statistical expertise |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Procedures

Core Analytical Workflow for ITC Implementation

Implementing a robust ITC requires meticulous attention to methodological details and validation procedures. The following diagram outlines the standard workflow for conducting and validating ITC analyses:

Standard Workflow for ITC Implementation

Protocol Details for Key ITC Methods

Network Meta-Analysis Protocol

NMA implementation requires specific methodological steps to ensure validity:

- Data Preparation: Extract relative treatment effects (log odds ratios, log hazard ratios) and their variances from each study. For time-to-event outcomes, extract number of events and log-rank statistics or hazard ratios [3].

- Consistency Assessment: Use node-splitting techniques to evaluate disagreement between direct and indirect evidence where both exist [3].

- Statistical Modeling: Implement either frequentist (using multivariate meta-analysis) or Bayesian approaches (using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods with non-informative priors) [3].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Present results with confidence/credible intervals and ranking probabilities, supplemented by sensitivity analyses exploring the impact of inclusion criteria and model choices [3].

Population-Adjusted ITC Protocol

MAIC implementation follows a distinct protocol when IPD is available for at least one study:

- Covariate Selection: Identify effect modifiers based on clinical knowledge and preliminary analyses [3].

- Propensity Score Estimation: Fit a logistic regression model comparing the index trial IPD to the aggregate comparator trial population [3].

- Weight Calculation: Assign weights to IPD patients using the method of moments to achieve balance on selected effect modifiers [3].

- Outcome Analysis: Fit weighted regression models to the IPD and combine with aggregate results from the comparator trial [3].

- Assess Effective Sample Size: Evaluate the loss of precision due to weighting and conduct bootstrap resampling for uncertainty estimation [3].

The acceptability of different ITC methods varies across HTA bodies worldwide, with clear preferences for certain methodologies based on their ability to minimize bias and adjust for confounding factors.

Current Acceptance Patterns

Recent analyses of HTA submissions reveal distinct patterns in the acceptance of various ITC methods:

Table 3: HTA Body Preferences and Acceptance of ITC Methods

| HTA Body | Preferred Methods | Less Favored Methods | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Medicines Agency (EMA) [24] | NMA, Population-adjusted methods | Naïve comparisons | Justification of similarity assumption; adequacy of statistical methods |

| Canada's Drug Agency (CDA-AMC) [24] | Anchored ITCs, MAIC | Unadjusted comparisons | Transparency; adjustment for cross-trial differences |

| Australian PBAC [24] | NMA, Adjusted comparisons | Unanchored comparisons | Clinical homogeneity; appropriate connectivity |

| French HAS [24] | PAIC, NMA | Naïve ITCs | Methodological rigor; relevance to decision context |

| German G-BA [24] | Advanced adjusted methods | Unadjusted ITCs (84% rejection rate) | Comprehensive adjustment for confounding |

Impact on Reimbursement Decisions

The strategic selection of ITC methods has demonstrated tangible impacts on HTA outcomes. Recent evidence indicates that orphan drug submissions incorporating ITCs were associated with a higher likelihood of positive recommendations compared to non-orphan submissions [24]. Furthermore, submissions employing population-adjusted or anchored ITC techniques were more favorably received by HTA bodies compared to those using naïve or unadjusted comparisons, reflecting agency preferences for methods with robust bias mitigation capabilities [24].

Analysis of recent oncology submissions reveals that among 188 unique HTA recommendations supported by 306 ITCs, authorities demonstrated greater acceptance of methods that explicitly addressed cross-study heterogeneity through statistical adjustment [24]. This underscores the importance of aligning method selection with both the evidence structure and HTA body expectations.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust ITCs requires both methodological expertise and appropriate analytical tools. The following table details key resources in the ITC researcher's toolkit:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ITC Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (gemtc, pcnetmeta) [3] | Bayesian NMA implementation | Complex evidence networks with sparse data |

| Stata (mvmeta, network) [3] | Frequentist NMA | Standard NMA with aggregate data | |

| SAS (PROC NLMIXED) [3] | Custom ITC implementation | Advanced simulation studies | |

| Specialized Packages | R (MAIC, SIC) [3] | Population-adjusted comparisons | Individual patient data scenarios |

| OpenBUGS/JAGS [3] | Bayesian hierarchical modeling | Complex evidence structures | |

| Quality Assessment | Cochrane Risk of Bias [3] | Study quality evaluation | Evidence assessment phase |

| GRADE for NMA [3] | Evidence quality rating | Results interpretation | |

| Data Visualization | Network graphs [3] | Evidence structure mapping | Study planning and reporting |

| Contribution plots [3] | Source of evidence visualization | Transparency in NMA |

Successful application of these tools requires interdisciplinary collaboration between health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) scientists and clinical experts. HEOR scientists contribute methodological expertise in identifying available evidence and designing statistically sound comparisons, while clinicians provide essential context for evaluating the clinical plausibility of assumptions and the relevance of compared populations and outcomes [3]. This collaboration ensures that selected ITC methods are both methodologically robust and clinically credible for HTA submissions.