A Practical Guide to Selecting Machine Learning Algorithms for Predictive ADMET Modeling

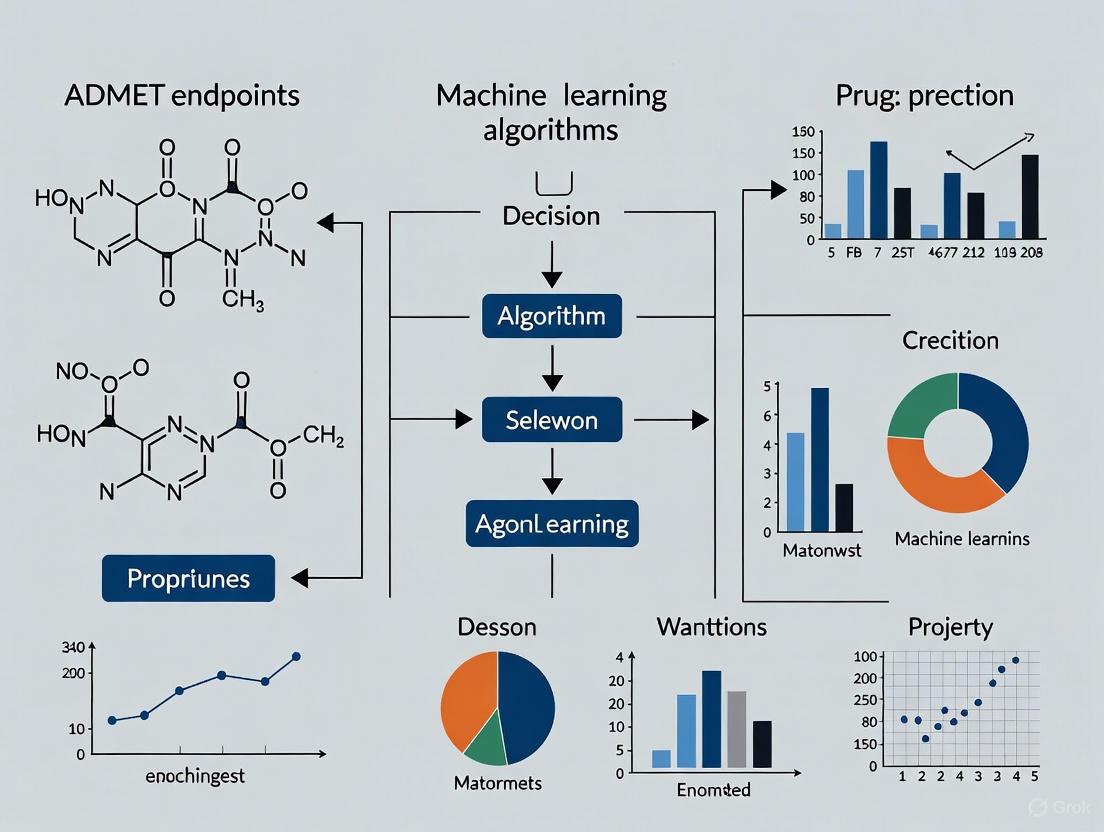

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select and apply machine learning algorithms for predicting specific Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET)...

A Practical Guide to Selecting Machine Learning Algorithms for Predictive ADMET Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select and apply machine learning algorithms for predicting specific Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) endpoints. It covers the foundational principles of machine learning in drug discovery, explores the application of specific algorithms like Graph Neural Networks and Random Forests to key ADMET properties, addresses common challenges such as data quality and model interpretability, and outlines robust validation and benchmarking strategies. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to build reliable in silico ADMET models, thereby accelerating lead optimization and reducing late-stage attrition in the drug development pipeline.

Machine Learning in ADMET Prediction: Building a Foundational Understanding

The Critical Role of ADMET Properties in Drug Development Success and Attrition

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common In Vitro ADME Assays

Q: I'm getting low cell viability with my cryopreserved hepatocytes after thawing. What could be wrong?

A: Low viability can result from several points in the handling process. Please review the following causes and recommendations [1].

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Improper thawing technique | Thaw cells rapidly (<2 minutes) in a 37°C water bath. Do not let the cell suspension sit in the thawing medium [1]. |

| Sub-optimal thawing medium | Use the recommended Hepatocyte Thawing Medium (HTM) to properly remove the cryoprotectant [1]. |

| Rough handling during counting | Use wide-bore pipette tips and mix the cell suspension slowly to ensure a homogenous mixture without damaging cells [1]. |

| Improper counting technique | Ensure cells are not left in trypan blue for more than 1 minute before counting, as this can affect viability readings [1]. |

Q: The monolayer confluency for my hepatocytes is sub-optimal after plating. What should I do?

A: Inconsistent monolayer formation often relates to attachment issues. Consider the following [1]:

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Insufficient time for attachment | Allow more time for cells to attach before overlaying with matrix. Compare culture morphology to the lot-specific characterization sheet [1]. |

| Poor-quality substratum | Use certified collagen I-coated plates to improve cell adhesion [1]. |

| Hepatocyte lot not characterized as plateable | Always check the lot specifications to confirm the cells are qualified for plating applications [1]. |

| Seeding density too low or high | Consult the lot-specific specification sheet for the correct seeding density and observe cells under a microscope post-seeding [1]. |

Q: My in vitro ADMET assay results are variable. What are the common underlying issues?

A: Variability in in vitro ADME assays is a recognized challenge. Key issues include [2]:

- Variability in Experimental Conditions: Small fluctuations in temperature, pH, enzyme concentration, or the presence of inhibitors can significantly alter results. Rigorous standardization and control of all variables are essential [2].

- Challenges with Metabolic Stability: Assays using liver microsomes or hepatocytes may not fully replicate in vivo metabolic processes, potentially missing important metabolites if not all pathways are accounted for [2].

- Issues with Drug Transporter Interactions: Different cell lines can exhibit variable transporter activity. Selecting validated models is critical for accurate prediction of a drug's distribution and excretion [2].

- Limitations in Predictive Accuracy: In vitro systems cannot fully replicate the complexity of a living organism. They may fail to predict drug-drug interactions or the impact of genetic variations on metabolism. Data should be interpreted with these limitations in mind [2].

Machine Learning for ADMET Prediction

Q: How can I select an appropriate machine learning algorithm for my specific ADMET endpoint?

A: The choice of algorithm depends on the nature of your data and the specific ADMET property you are predicting. Below is a structured guide to modern ML approaches [3] [4] [5].

Table: Machine Learning Algorithm Selection for ADMET Endpoints

| ADMET Endpoint Category | Recommended ML Algorithms | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Properties(e.g., Solubility, Permeability) | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Gradient Boosting [3] [4] | High interpretability, robust performance on structured descriptor data, less prone to overfitting with small datasets. | Feature engineering (molecular descriptors) is a prerequisite. May struggle with highly complex, non-linear relationships [4] [5]. |

| Complex Toxicity & Metabolism(e.g., hERG, CYP inhibition, Genotoxicity) | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Deep Neural Networks [3] [5] [6] | Directly learns from molecular structure (SMILES/graph); superior for capturing complex, non-linear structure-activity relationships. | Requires larger datasets; can be a "black box"; computational intensity is higher [5]. |

| Multiple Related Endpoints(Multi-task prediction) | Multi-Task Learning (MTL) Frameworks [7] [5] | Improved generalizability and data efficiency by leveraging shared knowledge across related tasks. | Model architecture and training are more complex; risk of negative transfer between unrelated tasks [5]. |

Q: What is the standard workflow for developing a robust ML model for ADMET prediction?

A: A systematic approach is crucial for building reliable models. The following workflow, supported by tools like admetSAR3.0 and RDKit, outlines the key stages [4] [7].

Q: What are the essential tools and reagents I need to set up for ADMET research?

A: Your toolkit should include both computational resources and laboratory reagents. Here is a summary of key solutions [7] [1].

Table: Research Reagent & Tool Solutions for ADMET Research

| Item/Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | In vitro model for studying hepatic metabolism, enzyme induction, and transporter activities [1]. | Ensure lot is qualified for plating and/or transporter studies. Use species-specific (e.g., human, rat) for relevance [1]. |

| Collagen I-Coated Plates | Provides a suitable extracellular matrix for hepatocyte attachment and formation of a confluent monolayer [1]. | Critical for maintaining hepatocyte health and function in culture. Use from recognized manufacturers [1]. |

| Specialized Cell Culture Media | Supports cell viability and function during thawing, plating, and incubation phases [1]. | Use Williams' Medium E with Plating and Incubation Supplement Packs or recommended Hepatocyte Thawing Medium (HTM) [1]. |

| admetSAR3.0 | A comprehensive public online platform for searching, predicting, and optimizing ADMET properties [7]. | Contains >370,000 experimental data points and predicts 119 endpoints using a multi-task graph neural network [7]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprinting [4] [6]. | Fundamental for feature engineering in many ML workflows for ADMET prediction [4]. |

| SwissADME | A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and medicinal chemistry friendliness of molecules [7]. | Useful for quick computational profiling of compounds [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the main advantage of using supervised learning for ADMET prediction? Supervised learning is highly effective for predicting specific, known ADMET endpoints because it uses labeled datasets to train models. This allows researchers to predict quantitative properties (e.g., solubility) or classify compounds (e.g., as CYP450 inhibitors) based on historical experimental data, making it ideal for tasks where the outcome is well-defined [4].

FAQ 2: When should I consider using unsupervised learning in my drug discovery pipeline? Unsupervised learning should be used for exploratory data analysis when you have unlabeled data or want to discover hidden patterns. Common applications in drug discovery include identifying novel patient subgroups with similar symptoms from medical records or segmenting chemical compounds based on underlying structural similarities without pre-defined categories [8].

FAQ 3: How does deep learning differ from traditional machine learning for ADMET? Deep learning, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs), automatically learns relevant features directly from complex molecular structures (like SMILES notations or graphs), bypassing the need for manually calculating and selecting molecular descriptors. This often leads to improved accuracy in modeling complex, non-linear structure-property relationships [9] [10].

FAQ 4: My model performs well on training data but poorly on new compounds. What might be wrong? This is a classic sign of overfitting. It can occur if your model is too complex for the amount of training data or if the training data is not representative of the new compounds you are testing. To address this, ensure you have a large and diverse dataset, use techniques like cross-validation and regularization, and simplify your model architecture if necessary [4] [5].

FAQ 5: Why is data quality so important for building robust ML models? The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" holds true. The performance and reliability of any ML model are directly dependent on the quality of the data used to train it. Noisy, incomplete, or biased data will lead to unreliable predictions, wasting computational resources and potentially leading to incorrect conclusions in the drug discovery process [4] [11].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance and Low Accuracy

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or Low-Quality Data | Check dataset size and for missing values/errors. | Collect more data or use data augmentation techniques. Clean and preprocess the data [4]. |

| Irrelevant Feature Set | Perform exploratory data analysis and correlation studies. | Apply feature selection methods (filter, wrapper, embedded) to identify the most predictive molecular descriptors [4]. |

| Incorrect Algorithm Choice | Benchmark different algorithms on a validation set. | Re-evaluate the problem: use supervised learning for labeled prediction, unsupervised for exploration, or deep learning for complex patterns [4] [5]. |

Issue 2: Model is Not Generalizing to New Data

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overfitting | Compare performance on training vs. validation datasets. | Introduce regularization (L1/L2), simplify the model, or use dropout in neural networks. Ensure proper train/test splits [4]. |

| Data Imbalance | Check the distribution of classes or target values. | Use sampling techniques (oversampling, SMOTE) or adjust class weights in the model [4]. |

| Incorrect Data Splitting | Verify if data splitting is random and stratified. | Use k-fold cross-validation to ensure the model is evaluated robustly across different data subsets [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key ML Applications in ADMET

Protocol 1: Building a Supervised Model for CYP450 Inhibition Classification

This protocol outlines the steps to create a classifier to predict whether a compound inhibits a key metabolic enzyme (e.g., CYP3A4).

- Data Collection: Source a labeled dataset from public repositories like the Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC), containing compound structures and their known inhibition status for the target CYP450 enzyme [9].

- Feature Engineering: Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., using RDKit) or generate molecular fingerprints from the compound's SMILES strings [4].

- Model Training: Split the data into training, validation, and test sets. Train multiple supervised algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines) on the training set. Optimize hyperparameters using the validation set [4] [9].

- Model Evaluation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using metrics such as AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, and recall [4].

Protocol 2: Applying Unsupervised Learning for Compound Library Exploration

This protocol uses clustering to identify inherent groupings in a compound library, which can help in lead series identification or library diversification.

- Data Preparation: Standardize the structures of all compounds in your library and compute a set of physicochemical descriptors [4].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of descriptors and mitigate the "curse of dimensionality." Use the first few principal components for clustering [8] [11].

- Clustering: Apply the K-Means clustering algorithm to the PCA-reduced data. Use the elbow method or silhouette analysis to determine the optimal number of clusters (k) [8].

- Analysis and Interpretation: Analyze the compounds within each cluster to identify common structural or property-based themes. This can reveal novel chemical series or areas of property space that are over/under-represented [11].

Protocol 3: Implementing a Deep Learning Model with Graph Neural Networks

This protocol describes using a GNN to predict aqueous solubility directly from molecular structure.

- Graph Representation: Convert the SMILES string of each molecule into a graph representation, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. Define node features (e.g., atom type, charge) [9].

- Model Architecture: Construct a Graph Neural Network, such as an attention-based GNN. This architecture processes the molecular graph and learns features by propagating information between connected atoms [9].

- Training: Train the model in a supervised manner using a dataset of molecules with experimentally measured solubility (e.g., from the AqSolDB database). Use a regression loss function like Mean Squared Error [9].

- Prediction and Interpretation: Use the trained model to predict solubility for new compounds. Some GNNs can provide insights into which atoms or substructures contributed most to the prediction [5] [9].

Workflow Visualization

ML Paradigm Selection Workflow for ADMET Research

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for ML-Driven ADMET Research

The following table details key computational "reagents" and resources required for conducting machine learning experiments in ADMET prediction.

| Resource Category | Examples | Function in ADMET Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Databases [4] | ChEMBL, PubChem, Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Provide large-scale, curated datasets of chemical structures and their associated biological and ADMET properties for model training and validation. |

| Descriptor Calculation Software [4] | RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon | Compute numerical representations (molecular descriptors, fingerprints) of chemical structures that serve as input features for traditional ML models. |

| Supervised ML Algorithms [4] [9] | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), XGBoost | Used to build predictive models for classification (e.g., toxic vs. non-toxic) and regression (e.g., predicting lipophilicity) tasks from labeled data. |

| Unsupervised ML Algorithms [8] [11] | K-Means, Hierarchical Clustering, PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | Used for exploratory data analysis, such as identifying inherent clusters in compound libraries or reducing feature space dimensionality for visualization. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks [9] [10] | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Transformers, Multi-task Learning Models | Automatically learn relevant features from raw molecular representations (e.g., graphs, SMILES), often achieving state-of-the-art accuracy on complex ADMET endpoints. |

| Model Evaluation Platforms [4] [5] | Scikit-learn, TDC Benchmarking Suite | Provide standardized metrics and protocols to rigorously evaluate and compare the performance of different ML models, ensuring robustness and generalizability. |

Essential Molecular Descriptors and Feature Representations for ADMET Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the most impactful molecular representations for general ADMET modeling, and how do I choose? The optimal choice often involves a hybrid approach. Recent benchmarks indicate that while individual representations like fingerprints or embeddings are effective, combining them systematically yields the best results [12]. The general hierarchy of performance often places descriptor-augmented embeddings at the top, followed by classical fingerprints and descriptors, and then single deep learning representations [13] [14]. The choice should be guided by your specific endpoint, dataset size, and need for interpretability versus pure predictive power. For a balanced approach, start with a combination of Mordred descriptors and Morgan fingerprints before exploring more complex embeddings [14] [4].

FAQ 2: Why does my model perform well in cross-validation but poorly on external test sets from different sources? This is a common issue in practical ADMET scenarios, primarily caused by the model encountering compounds outside its "applicability domain" learned from the training data [12] [15]. This often stems from differences in assay protocols, chemical space coverage, or experimental conditions between your training and the external source [12]. To mitigate this, ensure your training data is as diverse as possible, employ scaffold splitting during validation instead of random splits, and consider using federated learning approaches to incorporate data diversity without centralizing sensitive data [15]. Always test your model on a small, representative set from the external source before full deployment.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the interpretability of my deep learning-based ADMET models? While deep learning models like Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) can be "black boxes," several strategies enhance interpretability. One effective method is to integrate classical, interpretable descriptors (like RDKit descriptors) with deep-learned representations [14] [4]. This provides a handle for feature importance analysis. Furthermore, using post-hoc interpretation tools like SHAP or LIME on the input features can help. For graph-based models, attention mechanisms can highlight which substructures the model deems important for the prediction [14].

FAQ 4: What is the most robust way to compare different feature representation models? Beyond simple hold-out test sets, a robust evaluation integrates cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing [12]. This involves running multiple cross-validation folds for each model configuration and then applying statistical tests (like a paired t-test) to the resulting performance distributions to determine if the performance differences are statistically significant. This approach adds a layer of reliability to model assessments, which is crucial in a noisy domain like ADMET prediction [12].

FAQ 5: How critical is data cleaning and preprocessing for ADMET model performance? Data cleaning is a critical, non-negotiable step. Public ADMET datasets often contain inconsistencies such as duplicate measurements with varying values, inconsistent SMILES representations, and fragmented structures [12]. A standard cleaning protocol should include: canonicalizing SMILES, removing inorganic salts and organometallics, extracting parent compounds from salts, standardizing tautomers, and rigorously de-duplicating entries (removing inconsistent measurements) [12]. Studies show that proper cleaning can significantly reduce noise and improve model generalizability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance Has Plateaued Despite Trying Different Algorithms

- Possible Cause 1: Non-informative or redundant features. The feature set may lack the structural or physicochemical information needed to predict the specific endpoint.

- Solution: Implement a structured feature selection process. Start with filter methods (e.g., removing low-variance and highly correlated features) to quickly reduce dimensionality. Follow up with wrapper (e.g., recursive feature elimination) or embedded methods (e.g., using Random Forest feature importance) to identify the most predictive feature subset [4].

- Possible Cause 2: The chosen molecular representation is not suited for the task.

- Solution: Systematically explore and combine different representation classes. Do not just concatenate all available features without reasoning. Follow a iterative process: start with a baseline representation (e.g., ECFP fingerprints), then test other types (e.g., Mol2Vec embeddings, RDKit descriptors), and finally, evaluate intelligent combinations of the top performers [12] [13].

- Possible Cause 3: The dataset may contain hidden biases or errors.

- Solution: Re-audit your dataset using the cleaning procedures outlined in the FAQs. Visualize the chemical space using tools like DataWarrior to identify outliers or clusters that might skew the model [12].

Problem: Poor Generalization to Novel Chemical Scaffolds

- Possible Cause 1: The training data lacks sufficient diversity in chemical space.

- Solution: Incorporate external data sources to expand chemical coverage. If external data cannot be centralized due to privacy, consider federated learning, which allows training on distributed datasets across multiple institutions, systematically expanding the model's applicability domain [15].

- Possible Cause 2: The model is overfitting to specific substructures prevalent in the training set.

- Solution: Use scaffold splitting instead of random splitting during model validation to ensure you are testing the model's ability to generalize to entirely new chemotypes [12]. Apply stronger regularization during training and consider using simpler models or reducing model complexity.

Problem: Inconsistent Predictions Across Different Software Tools

- Possible Cause 1: Differences in the underlying descriptor calculation or fingerprint implementation.

- Solution: Standardize your preprocessing pipeline. Use a single, well-documented toolkit (like RDKit) for all descriptor and fingerprint calculations to ensure consistency [12]. When comparing tools, note the exact definitions and parameters (e.g., for Morgan fingerprints, the radius and bit length).

- Possible Cause 2: The models were trained on different benchmark datasets with varying data quality and endpoints.

- Solution: When evaluating different tools, benchmark them on a small, internally consistent validation set you have high confidence in. Always verify the training data and endpoint definitions for any pre-trained model you use [14].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Representations Across Key ADMET Endpoints

This table summarizes how different molecular representations perform on common ADMET tasks, based on benchmarking studies. Performance is a generalized score (Poor to Excellent) reflecting predictive accuracy and robustness.

| ADMET Endpoint | Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP) | RDKit 2D Descriptors | Mol2Vec Embeddings | Descriptor-Augmented Mol2Vec | Message Passing NN (Graph) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility | Good | Good | Very Good | Excellent [13] | Very Good |

| CYP450 Inhibition | Very Good | Good | Good | Excellent [13] | Excellent [14] |

| Human Intestinal Absorption | Good | Very Good | Good | Excellent [13] | Very Good |

| hERG Cardiotoxicity | Very Good | Fair | Good | Excellent [13] | Very Good |

| Hepatotoxicity | Good | Fair | Very Good | Excellent [13] [14] | Very Good |

| Plasma Protein Binding | Good | Good | Good | Excellent [13] | Good |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Modeling

A curated list of key software tools and libraries for calculating molecular descriptors and building models.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in ADMET Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [12] [4] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Calculates a wide array of molecular descriptors (rdkit_desc), Morgan fingerprints, and handles molecular standardization. |

| Mordred [14] | Open-Source Descriptor Calculator | Computes a comprehensive set of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors (>1800), expanding beyond RDKit's standard set. |

| Mol2Vec [13] [14] | Unsupervised Embedding Algorithm | Generates continuous vector representations of molecules by learning from chemical substructures, analogous to Word2Vec in NLP. |

| Chemprop [12] [14] | Deep Learning Framework | Implements Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) for molecular property prediction, directly learning from molecular graphs. |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio [16] | Commercial Software Suite | Provides integrated tools for QSAR, ADMET prediction, and toxicology using both proprietary and user-generated models. |

| ADMETlab 3.0 [14] | Web-Based Platform | Offers a user-friendly platform for predicting a wide range of ADMET endpoints using multi-task learning models. |

Workflow Diagram: Systematic Feature Selection and Model Evaluation

Systematic Feature Selection and Model Evaluation

Methodology: Protocol for Structured Feature Representation Selection

This protocol outlines a step-by-step process for selecting the most effective feature representations for a given ADMET endpoint, as validated in recent literature [12] [13].

1. Data Preparation and Cleaning:

- SMILES Standardization: Use a standardized tool (e.g., from RDKit or a customized ruleset) to canonicalize all SMILES strings. This includes handling tautomers, ionization, and removing stereochemistry if not required [12].

- Salt Stripping and Parent Compound Extraction: Remove counterions and extract the primary organic parent compound to ensure consistency, as properties are often attributed to the parent structure [12].

- Deduplication: Identify and remove duplicate compounds. For duplicates with conflicting property values, either keep the consensus value or remove the entire group to avoid noise [12].

2. Baseline Model Establishment:

- Split the cleaned data into training and test sets using scaffold splitting to ensure a challenging and realistic evaluation of generalizability to new chemotypes [12].

- Choose a simple, well-understood model architecture (e.g., Random Forest or a simple Multi-Layer Perceptron) as a baseline.

- Train and evaluate this model using a single, common representation (e.g., Morgan Fingerprints with radius 2 and 2048 bits) as a baseline. Use cross-validated performance metrics (e.g., AUC-ROC, RMSE) on the training set.

3. Iterative Feature Combination and Evaluation:

- Iteration: Systematically train and evaluate the baseline model with other individual representations:

- Classical Descriptors: A curated set of RDKit 2D descriptors.

- Unsupervised Embeddings: Mol2Vec embeddings (e.g., 300 dimensions) [13].

- Deep Learned Features: Features extracted from a pre-trained graph neural network.

- Combination: Create concatenated feature sets by combining the top-performing individual representations from the previous step (e.g., Morgan Fingerprints + Mol2Vec, or Mol2Vec + RDKit Descriptors).

- Evaluation with Statistical Testing: For each representation and combination, perform k-fold cross-validation. Instead of just comparing mean performance, apply statistical hypothesis testing (e.g., a paired t-test on the cross-validation folds) to determine if the performance improvement over the baseline is statistically significant [12].

4. Final Model Selection and Practical Validation:

- Select the feature representation that provides the best statistically significant performance.

- Evaluate the final model, trained with the selected features, on the held-out internal test set.

- For the strongest validation, evaluate the model on an external test set from a different data source for the same property. This assesses the model's practical utility in a real-world scenario [12].

In modern drug discovery, the evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a critical bottleneck, contributing significantly to the high attrition rate of drug candidates. Machine learning (ML) models have emerged as transformative tools for predicting these properties, offering rapid, cost-effective alternatives to traditional experimental approaches that are often time-consuming and limited in scalability [4]. The foundation of any robust ML model is high-quality, comprehensive data. This technical support guide provides researchers with essential information on public databases and methodologies for ADMET model training, framed within the context of selecting appropriate machine learning algorithms for specific ADMET endpoints research.

Comprehensive ADMET Database Directory

The table below summarizes key public databases relevant for ADMET model training, highlighting their specific applications and data characteristics.

| Database Name | Primary Focus & Utility in ADMET | Key Data Content & Statistics | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [17] [18] | Bioactivity data for target identification, SAR analysis, and efficacy-related property prediction. | Over 2.4 million compounds; 20.3 million bioactivity measurements (e.g., IC50, Ki) [17]. | Free public access; web interface, RESTful API [17]. |

| PubChem [17] [19] | Largest free chemical repository for compound identification, bioassays, and toxicity prediction. | 119 million+ compounds; extensive bioassay and toxicity data from NIH, EPA, and other sources [17]. | Free public access [17]. |

| DrugBank [17] | Drug development, pharmacovigilance, and ADMET prediction for approved and experimental drugs. | Over 17,000 drug entries; 5,000+ protein targets; pharmacokinetic data [17]. | Free for non-commercial use [17]. |

| ZINC [17] | Virtual screening and hit identification for early-stage discovery; provides ready-to-dock compounds. | 54.9 billion molecules; 5.9 billion with 3D structures; pre-filtered for drug-like properties [17]. | Free public access [17]. |

| BindingDB [17] [18] | Binding affinity prediction, QSAR modeling, and understanding ligand-receptor interactions. | 3 million+ binding affinity data points (Kd, Ki, IC50) for 1.3 million+ compounds [17]. | Free public access [17]. |

| TCMSP [17] | Herbal medicine research, multi-target drug discovery, and natural product ADMET prediction. | 500+ herbal medicines; 30,000+ compounds with associated ADMET properties [17]. | Free public access [17]. |

| HMDB [17] | Metabolomics research, biomarker discovery, and understanding human metabolism & toxicity. | 220,000+ human metabolites with spectral, clinical, and biochemical data [17]. | Free public access [17]. |

| PharmaBench [18] | Curated benchmark for ADMET predictive model evaluation, addressing limitations of prior sets. | 11 ADMET properties; 52,482 entries compiled from ChEMBL, PubChem, etc. [18]. | Open-source dataset. |

| ADMETlab 3.0 [19] | Integrated web platform for predicting a wide array of ADMET endpoints and related properties. | Covers 119 endpoints; database of over 400,000 molecules for model building [19]. | Free webserver; no registration required. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the most common data quality issues in public ADMET datasets, and how can I address them? Common issues include data imbalance, inconsistent experimental conditions, and the presence of non-drug-like compounds [4] [18]. To address these:

- For Imbalanced Data: Apply data sampling techniques (e.g., SMOTE) combined with feature selection to improve model performance on minority classes [4].

- For Inconsistent Data: Utilize recently developed benchmarking sets like PharmaBench, which employ Large Language Models (LLMs) to extract and standardize experimental conditions from assay descriptions, ensuring more consistent data for model training [18].

- For Data Relevance: Filter compounds based on drug-likeness rules (e.g., molecular weight between 300-800 Daltons) to better align with the chemical space of drug discovery projects [18].

FAQ 2: My model performs well on the test set but generalizes poorly to new compound series. What could be wrong? This is often a problem of model overfitting or dataset bias. The training data may lack sufficient structural diversity or contain hidden biases.

- Solution: Implement a scaffold split during dataset division, where compounds are split based on their molecular core structure, rather than a random split. This tests the model's ability to generalize to truly novel chemotypes [18].

- Action: Use benchmarks that provide scaffold-based splits to validate your model's generalizability more rigorously [18].

FAQ 3: Which molecular representation should I use for my ADMET prediction task? The choice of representation can significantly impact model accuracy.

- Graph-Based Representations: Methods like Directed Message Passing Neural Networks (DMPNN) learn features directly from the molecular graph and have achieved state-of-the-art accuracy by capturing complex structural patterns [19].

- Molecular Descriptors: Traditional 2D and 3D descriptors (e.g., calculated using RDKit) provide a fixed-length numerical summary of a molecule's physicochemical properties [4].

- Hybrid Approach: For superior performance, combine both methods. As demonstrated in ADMETlab 3.0, integrating graph-based features with RDKit 2D descriptors allows global molecular information from descriptors to complement local structural information learned by the graph network [19].

FAQ 4: How can I assess the reliability of a prediction from my ADMET model? Trust in model predictions is crucial for decision-making in drug discovery.

- Solution: Implement uncertainty estimation. Advanced platforms like ADMETlab 3.0 use evidential deep learning to quantify the uncertainty of each prediction. This helps identify when a molecule is outside the model's reliable prediction domain, allowing researchers to prioritize compounds for which the model is most confident [19].

Experimental Protocols for Data Curation and Model Training

Protocol 1: Data Collection and Standardization Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for building a robust, curated ADMET dataset from public sources, a critical first step for reliable model training [18].

Procedure:

- Data Aggregation: Collect raw data entries from multiple public databases such as ChEMBL and PubChem. This initial pool often contains hundreds of thousands of entries [18].

- Condition Extraction: Utilize a multi-agent Large Language Model (LLM) system to parse unstructured assay descriptions and identify critical experimental conditions (e.g., buffer type, pH). This step is vital for reconciling results from different sources [18].

- Data Merging: Combine entries from various sources based on standardized compound identifiers and experimental conditions.

- Data Standardization & Filtering:

- Structure Processing: Neutralize salts, remove counterions, and generate canonical SMILES strings [19].

- Curation: Remove organometallic compounds, isomeric mixtures, and other non-standard chemistries to ensure data quality [19].

- Drug-Likeness Filtering: Apply filters (e.g., molecular weight) to retain compounds relevant to drug discovery projects [18].

- Deduplication: Remove duplicate experimental results for the same compound under the same conditions to prevent data leakage [18].

Protocol 2: Building a Multi-Task DMPNN Model for ADMET Endpoints

This protocol describes the methodology for constructing a high-performance predictive model using a multi-task deep learning architecture, as implemented in state-of-the-art platforms like ADMETlab 3.0 [19].

Procedure:

- Input Representation: Represent each molecule by its SMILES string. Convert this into two parallel inputs: a molecular graph (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) and a vector of pre-calculated RDKit 2D molecular descriptors [19].

- Model Architecture:

- DMPNN Encoder: Process the molecular graph using a Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN). This architecture learns meaningful atomic and bond embeddings by passing messages along the directed edges of the graph, effectively capturing complex local structural patterns [19].

- Feature Aggregation: Generate a final graph representation (readout) and concatenate it with the RDKit 2D descriptor vector. This hybrid approach combines the strengths of both representation types [19].

- Multi-Task Learning: Feed the concatenated feature vector into a feed-forward neural network with multiple output nodes, each corresponding to a different ADMET endpoint. This allows the model to learn shared representations across related tasks, improving generalization and efficiency [19].

- Model Training & Validation:

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the dataset into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets. The validation set is used for hyperparameter tuning [19].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Use optimizers like Adam and employ Bayesian optimization to find the best model hyperparameters [19].

- Performance Evaluation: For classification tasks, use metrics like AUC-ROC, Accuracy, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). For regression tasks, use R², RMSE, and MAE [19].

The table below lists key software, databases, and computational resources essential for ADMET modeling research.

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in ADMET Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [20] [19] | Cheminformatics Software | Open-source toolkit for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprinting, and handling chemical data. Essential for feature engineering. |

| Chemprop [19] | Deep Learning Library | Specialized package for training DMPNN models on molecular property prediction tasks, enabling state-of-the-art graph-based learning. |

| Scopy [20] [19] | Toxicology & Medicinal Chemistry Tool | Used for generating toxicophore alerts and applying medicinal chemistry rules to assess compound safety and quality. |

| ADMETlab 3.0 [19] | Integrated Web Platform | Provides a comprehensive suite of over 100 pre-built ADMET prediction models, useful for rapid property profiling and benchmarking. |

| PharmaBench [18] | Curated Benchmark Dataset | Provides a high-quality, standardized dataset for training and fairly evaluating new ADMET prediction models on key properties. |

| Multi-Agent LLM System [18] | Data Curation Tool | A system leveraging Large Language Models (e.g., GPT-4) to automate the extraction and standardization of experimental conditions from scientific text, revolutionizing data curation. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common data quality issues in public ADMET datasets, and how can I address them? Public ADMET datasets often suffer from inconsistent SMILES representations, duplicate measurements with conflicting values, and mislabeled compounds [12]. A robust data cleaning protocol is essential. This should include:

- Standardizing SMILES: Use tools to canonicalize SMILES strings, adjust tautomers, and remove inorganic salts or organometallic compounds [12].

- Handling Salts: Extract the organic parent compound from salt forms, being cautious with salt components that could themselves be organic molecules (e.g., citrate) [12].

- Deduplication: Remove inconsistent duplicates (where the same compound has different target values) and keep only the first entry for consistent duplicates [12].

Q2: My model performs well on the test set but fails on new, real-world compounds. What is the likely cause? This is often a problem of data representativeness. Many benchmark datasets contain compounds with molecular properties (e.g., lower molecular weight) that differ substantially from those used in industrial drug discovery pipelines [18]. To mitigate this:

- Use scaffold splitting instead of random splitting for train/test splits to better assess performance on novel chemotypes [15] [12].

- Validate your model on an external dataset from a different source, if available, to simulate a real-world scenario [12].

- Consider leveraging larger, more diverse benchmark sets like PharmaBench that are designed to better represent drug-like chemical space [18].

Q3: How do I choose the right molecular representation (features) for my ADMET prediction task? The optimal feature representation is often dataset-dependent [12]. A systematic approach is recommended:

- Do not arbitrarily concatenate multiple representations at the onset without reasoning [12].

- Iteratively test different representations—such as RDKit descriptors, Morgan fingerprints, and deep-learned embeddings—and their combinations [12].

- Use a structured feature selection process (filter, wrapper, or embedded methods) to identify the most relevant features and reduce redundancy [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Generalization and Overfitting

Description: The model achieves high accuracy on the training data but performs poorly on the validation or test sets.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Check Data Splitting: Ensure you are using scaffold splitting to evaluate the model's ability to generalize to new chemical structures, not just random splitting [12].

- Apply Regularization: Techniques like L1 (Lasso) or L2 (Ridge) regularization can penalize complex models and reduce overfitting [21].

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the number of model layers or parameters if using a deep neural network. For tree-based models, limit the maximum depth or increase the minimum samples required to split a node [21].

- Use Cross-Validation with Statistical Testing: Implement k-fold cross-validation and use statistical hypothesis tests to compare models robustly, ensuring performance improvements are real and not due to random chance [12].

Problem: Severe Class Imbalance in a Toxicity Endpoint

Description: For a classification task (e.g., toxic vs. non-toxic), one class has significantly fewer samples, causing the model to be biased toward the majority class.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Resample the Data: Use oversampling techniques (e.g., SMOTE) for the minority class or undersampling for the majority class to create a balanced dataset [4].

- Adjust Class Weights: Most ML algorithms allow you to assign higher weights to the minority class during training, forcing the model to pay more attention to it [4].

- Combine Feature Selection with Sampling: Empirical results suggest that performing feature selection on resampled data can lead to better performance than feature selection on the original imbalanced data [4].

Problem: Data Leakage Leading to Over-optimistic Performance

Description: The model demonstrates performance that seems "too good to be true," often because information from the test set has inadvertently been used during the training process.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Withhold Validation Dataset: Keep a final validation dataset completely separate until the model development and hyperparameter tuning are fully complete [21].

- Perform Data Preparation within Cross-Validation Folds: When doing scaling or other preprocessing, recalculate parameters (e.g., mean and standard deviation) separately for each training fold to prevent the validation fold from influencing the training process [21].

- Use Automated Pipelines: Leverage tools like

scikit-learnPipelines or R'scaretpackage to automate and encapsulate the preprocessing steps within the cross-validation loop, preventing data leakage [21].

Description: When merging ADMET data from public databases like ChEMBL, the same compound has different experimental values for the same property, making it difficult to create a unified dataset.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Extract Experimental Conditions: Use a multi-agent LLM system or carefully review assay descriptions to identify critical experimental conditions (e.g., buffer type, pH, experimental procedure) that cause variability [18].

- Standardize and Filter: After identifying conditions, standardize the units and filter the data to include only entries that meet consistent experimental criteria before merging [18].

- Remove Inconsistent Duplicates: If the same compound under the same experimental conditions has vastly different values, consider removing these entries as they introduce noise [12].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Comparison of Common ML Algorithms for ADMET Endpoints

| Algorithm | Best Suited For | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Various ADMET tasks, often a strong baseline [12] | Robust to outliers, handles non-linear relationships [4] | Performance can be dataset-dependent; may not be optimal for all endpoints [12] |

| Gradient Boosting (e.g., LightGBM, CatBoost) | Tasks requiring high predictive accuracy [12] | Often achieves state-of-the-art performance on tabular data [12] | Can be more prone to overfitting without careful hyperparameter tuning |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | High-dimensional data [4] | Effective in complex feature spaces [4] | Performance heavily dependent on kernel and hyperparameter selection |

| Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN) | Leveraging inherent molecular graph structure [12] | Learns task-specific features directly from molecular graph [4] | Higher computational cost; requires more data for training |

Table 2: Key Data Quality Metrics and Benchmarks from PharmaBench

| Metric / Aspect | Typical Challenge in Older Benchmarks (e.g., ESOL) | Improvement in PharmaBench |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Size | ~1,128 compounds for solubility [18] | 52,482 total entries across 11 ADMET properties [18] |

| Molecular Weight Representativeness | Mean MW: 203.9 Da (not drug-like) [18] | Covers drug-like space (MW 300-800 Da) [18] |

| Data Source Diversity | Limited fraction of public data used [18] | Integrated 156,618 raw entries from multiple sources [18] |

| Experimental Condition Annotation | Often missing, leading to inconsistent merged data [18] | Uses an LLM multi-agent system to extract key conditions from 14,401 bioassays [18] |

| Item / Resource | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit; calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints [12] | Used to generate >5000 molecular descriptors and Morgan fingerprints [4] [12] |

| PharmaBench | A comprehensive, open-source benchmark set for ADMET properties [18] | Contains 11 standardized datasets designed to be more representative of drug discovery compounds [18] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | A platform providing curated datasets and benchmarks for drug discovery [12] | Hosts an ADMET leaderboard for comparing model performance [12] |

| Chemprop | A message-passing neural network (MPNN) package specifically designed for molecular property prediction [12] | Can use learned representations from molecular graphs for ADMET tasks [12] |

| scikit-learn / Caret | Extensive libraries for classical ML models, preprocessing, and pipeline creation [21] | Essential for implementing cross-validation, feature selection, and preventing data leakage [21] |

| Multi-agent LLM System | Automates the extraction of experimental conditions from unstructured bioassay descriptions [18] | Key for curating consistent datasets from sources like ChEMBL [18] |

Standard ML Workflow for ADMET Prediction

The diagram below outlines the standard workflow for developing a machine learning model for ADMET prediction, from raw data to a validated model, highlighting key decision points.

Detailed Methodology for a Robust Model Comparison Experiment

This protocol outlines the steps for a statistically sound comparison of machine learning models and feature representations for a specific ADMET endpoint, as described in benchmarking studies [12].

Objective: To identify the optimal model and feature representation combination for a given ADMET prediction task and evaluate its performance in a practical, external validation scenario.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Obtain a dataset for your target ADMET property (e.g., from TDC or PharmaBench).

- Apply the data cleaning protocol detailed in FAQ A1, including SMILES standardization, salt removal, and deduplication.

- Baseline Model and Feature Establishment:

- Split the cleaned data using a scaffold split to ensure compounds in the test set have distinct molecular scaffolds from the training set.

- Train a baseline model (e.g., Random Forest) using a standard feature representation (e.g., RDKit descriptors).

- Evaluate performance on the test set using relevant metrics (e.g., AUC-ROC for classification, RMSE for regression).

- Iterative Feature and Model Optimization:

- Feature Combination: Systematically train and evaluate your model using different feature representations (e.g., Morgan fingerprints, deep-learned embeddings) and their combinations. Avoid arbitrary concatenation.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: For the most promising feature sets, perform hyperparameter optimization for the model.

- Statistical Validation: Use cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing (e.g., paired t-tests on CV folds) to determine if performance improvements from optimization steps are statistically significant.

- Practical Scenario Evaluation:

- External Validation: Take the final optimized model trained on your primary dataset and evaluate it on a separate test set from a different source (e.g., an in-house dataset or another public dataset for the same property).

- Data Combination: To simulate the use of external data, train a new model on a combination of data from your primary source and the external source. Evaluate how this affects performance compared to using only internal data.

Algorithm Selection Guide: Mapping ML Models to Specific ADMET Endpoints

The high attrition rate of drug candidates is frequently due to unfavorable Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. Early and accurate prediction of these endpoints is therefore critical for improving the efficiency of drug development [4]. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool, providing rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible models that integrate seamlessly into discovery pipelines. This technical support center focuses on the application of ML algorithms for predicting three critical absorption-related endpoints: solubility, permeability, and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate classification, guiding researchers in selecting and implementing the right models for their experiments [4].

Algorithm Selection Guide

Selecting the appropriate algorithm depends on your specific endpoint, dataset size, and the nature of your molecular descriptors. The following table summarizes the recommended algorithms for each endpoint.

Table 1: Machine Learning Algorithms for Key ADMET Endpoints

| ADMET Endpoint | Recommended ML Algorithms | Typical Molecular Descriptors | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Graph Neural Networks (GNN) [4] | Constitutional, topological, electronic, and quantum-chemical descriptors [4] | Data quality is paramount; models are sensitive to the accuracy of experimental training data. |

| Permeability | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees, Neural Networks [4] | Hydrogen-bonding descriptors, molecular weight, polar surface area [4] | The choice of in vitro permeability model (e.g., Caco-2, PAMPA) used for training will impact predictions. |

| P-gp Substrate Classification | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, Kohonen's Self-Organizing Maps (Unsupervised) [4] | 2D and 3D molecular descriptors derived from specialized software [4] | Feature selection methods (e.g., filter, wrapper) can help identify the most relevant molecular properties [4]. |

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the scientific basis for classifying drugs based on solubility and permeability? The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) provides the foundational framework. It categorizes drugs into four classes based on their aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability, which allows for the prediction of the intestinal absorption rate-limiting step [22]:

- Class I (High Solubility, High Permeability): Absorption is typically rapid and complete.

- Class II (Low Solubility, High Permeability): Dissolution is the rate-limiting step for absorption.

- Class III (High Solubility, Low Permeability): Permeability is the rate-limiting step.

- Class IV (Low Solubility, Low Permeability): Absorption is challenging and highly variable.

Q2: Why is it crucial to predict P-gp substrate status early in drug discovery? P-gp is a major efflux transporter in the intestine, liver, and blood-brain barrier. A drug that is a P-gp substrate can have its absorption limited, be actively pumped out of cells, and exhibit altered distribution and excretion, ultimately impacting its overall bioavailability and potential for drug-drug interactions [22].

Q3: My ML model performs well on training data but poorly on new compounds. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of overfitting. Solutions include:

- Increase Training Data: Use a larger and more diverse dataset of compounds.

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the number of features using feature selection techniques (e.g., filter, wrapper, or embedded methods) to avoid learning noise [4].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Adjust parameters to reduce model complexity.

- Cross-Validation: Always use rigorous k-fold cross-validation during training to get a better estimate of real-world performance [4].

Q4: What are the best practices for validating an ML model for regulatory purposes? While regulatory acceptance is evolving, best practices include:

- Use of High-Quality Data: Employ reliable, experimentally-derived data for training.

- External Validation Set: Test the final model on a completely independent, held-out dataset not used in training or optimization.

- Model Interpretability: Where possible, use models that provide insight into which molecular features are driving the prediction.

- Alignment with Guidelines: Reference established scientific guidelines, such as the FDA's BCS guidance, to frame the utility of your model [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Permeability Predictions

- Possible Cause 1: The model was trained on permeability data from a specific in vitro system (e.g., Caco-2) and is being applied to compounds outside its chemical domain.

- Solution: Verify the applicability domain of the model. Retrain the model with data that better matches your compound library.

- Possible Cause 2: Key molecular descriptors related to efflux transport (e.g., for P-gp) are not being adequately captured.

- Solution: Incorporate additional descriptors specific to transporter interactions or use a graph-based model that can learn more complex structural features [4].

Problem: Poor Solubility Prediction for a Particular Chemical Series

- Possible Cause: The training data may lack sufficient examples of similar chemical motifs, leading to poor generalization.

- Solution: Apply data augmentation techniques or transfer learning. If possible, generate a small amount of high-quality experimental data for your specific chemical series and fine-tune the model.

Problem: Model Performance is Highly Sensitive to Small Changes in the Input Features

- Possible Cause: The model may be relying on a few highly specific, non-generalizable features, or the input data may have high variance.

- Solution: Re-examine the feature selection process. Implement more robust data preprocessing and normalization steps. Using ensemble methods like Random Forest can often mitigate this issue [4].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a Supervised ML Model for P-gp Substrate Classification

This protocol outlines the steps to create a binary classifier to predict whether a compound is a P-gp substrate.

Data Curation:

- Collect a dataset of known P-gp substrates and non-substrates from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) or proprietary sources.

- Ensure the dataset is well-balanced to avoid model bias.

Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing:

- Use cheminformatics software (e.g., RDKit, PaDEL) to calculate a wide range of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors for each compound [4].

- Clean the data by removing descriptors with zero variance and imputing missing values if necessary.

- Normalize the descriptor values to a common scale (e.g., 0 to 1).

Feature Selection:

Model Training and Validation:

- Split the data into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets.

- Train multiple algorithms (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) on the training set using the selected features.

- Evaluate model performance on the test set using metrics like Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Model Generalizability with k-Fold Cross-Validation

This methodology is critical for obtaining a robust estimate of your model's performance.

- Partition the Data: Randomly split the entire dataset into 'k' equal-sized folds (commonly k=5 or k=10).

- Iterative Training and Testing:

- For each unique fold: a) Designate the current fold as the test set. b) Use the remaining k-1 folds as the training data. c) Train the model on the training set and evaluate it on the test set. d) Record the performance metric(s).

- Calculate Final Performance: Compute the average and standard deviation of the performance metrics from the 'k' iterations. This provides a more reliable measure of how the model will perform on unseen data [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for ML-Based ADMET Prediction

| Tool / Resource Type | Example(s) | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay [4] | Sources of curated, experimental ADMET data for model training and validation. |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | RDKit, PaDEL, Dragon [4] | Calculates thousands of numerical representations (descriptors) from chemical structures for use as model inputs. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch [4] | Libraries providing implementations of various ML algorithms for building and training predictive models. |

| Feature Selection Methods | Filter (CFS), Wrapper (RFE), Embedded (LASSO) [4] | Techniques to identify the most relevant molecular descriptors, improving model accuracy and interpretability. |

| Model Evaluation Metrics | AUC-ROC, F1-Score, Precision, Recall [4] | Quantitative measures to assess and compare the performance of different classification models. |

Visualizing the Algorithm Selection Logic

The following diagram provides a logical flowchart to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate machine-learning approach based on their research question and data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key advantages of using machine learning over traditional methods for predicting distribution parameters?

Machine learning (ML) models offer significant advantages in predicting Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) and Volume of Distribution at steady state (VDss). ML approaches provide rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible alternatives that seamlessly integrate into early drug discovery pipelines. A key strength is their ability to handle large datasets and decipher complex, non-linear structure-property relationships that traditional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models often miss [4] [5]. For instance, state-of-the-art ML models for PPB have demonstrated a high coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.90-0.91 on training and test sets, outperforming previously reported models [23]. Furthermore, run times for ML models are drastically lower—from one second to a few minutes—compared to the several hours required for traditional mechanistic pharmacometric models [24].

FAQ 2: Which machine learning algorithms are most effective for predicting VDss and PPB?

Random Forest and XGBoost are consistently highlighted as top-performing algorithms for distribution-related predictions [24] [25]. For predicting entire pharmacokinetic series, XGBoost has shown superior performance (R²: 0.84), while LASSO regression has excelled in predicting area under the curve parameters (R²: 0.97) [24]. Ensemble models and graph neural networks are also gaining prominence for their improved accuracy and ability to learn task-specific molecular features [4] [5]. The optimal algorithm can be dataset-dependent, and a structured approach to model selection, including hyperparameter tuning and cross-validation, is recommended [12].

FAQ 3: My model performance is poor. What is the most likely cause and how can I address it?

Poor model performance is most frequently linked to data quality and feature representation [4] [12]. To address this:

- Data Cleaning: Implement a strict data curation protocol. This includes standardizing molecular representations (e.g., SMILES strings), removing inorganic salts and duplicates, and handling inconsistent measurements [23] [12].

- Feature Engineering: Move beyond simply concatenating different molecular descriptors. Systematically evaluate and select feature representations (e.g., fingerprints, descriptors, graph-based features) that are statistically significant for your specific dataset and endpoint [12].

- Data Imbalance: If your dataset has an imbalance (e.g., fewer high-PPB compounds), employ techniques like feature selection combined with data sampling to improve prediction performance for underrepresented classes [4].

FAQ 4: Are there publicly available models or platforms I can use for predicting PPB and VDss?

Yes, several robust public platforms have emerged. The OCHEM platform hosts a state-of-the-art PPB prediction model that has been both retrospectively and prospectively validated [23]. For Volume of Distribution and other PK parameters, PKSmart is an open-source, web-accessible tool that provides predictions with performance on par with industry-standard models [25]. These resources allow researchers to integrate in silico predictions of distribution early in their design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles without the need for extensive internal model development.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Predictive Accuracy for High PPB Compounds

- Symptoms: The model performs well for low and medium PPB compounds but shows significant errors for compounds with high binding rates.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Audit Training Data: Check the distribution of PPB values in your training set. A low number of high-PPB compounds is a common cause. Consider data sampling techniques to address this imbalance [4].

- Feature Analysis: Investigate if the model is leveraging the correct structural and physicochemical features. Some studies have identified specific characteristics of high-PPB molecules; incorporating knowledge of these can guide feature selection or data augmentation [23].

- Model Selection: Explore ensemble or consensus modeling approaches, which have been shown to improve prediction accuracy and robustness, especially for challenging endpoints like high PPB [23].

Problem: Model Fails to Generalize to External Test Set

- Symptoms: The model shows excellent performance on internal validation (e.g., cross-validation) but performs poorly on a new, external dataset from a different source.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Assess Data Consistency: This is a classic sign of data mismatch. rigorously clean and standardize both your training and external test sets to ensure molecular representations and measurement criteria are consistent [12].

- Evaluate Applicability Domain: The new compounds may lie outside the chemical space covered by your training data. Use applicability domain estimation techniques to identify these compounds and interpret their predictions with caution [25].

- Incorporate External Data: If the external data is reliable, retrain your model on a combination of the original training data and the new external data. This can enhance the model's robustness and generalizability, as demonstrated in practical benchmarking studies [12].

Problem: Inaccurate VDss Predictions Despite Good Structural Descriptors

- Symptoms: The model uses comprehensive molecular fingerprints and descriptors, yet predictions for VDss are unreliable.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Incorporate Cross-Species Patterns: VDss is influenced by complex mechanisms like tissue binding. Integrate predicted animal PK parameters (e.g., from rat, dog, or monkey) as additional input features. This approach, used by PKSmart, leverages biological patterns to significantly enhance human VDss prediction (external R²: 0.39) [25].

- Verify Data Source: Ensure your VDss data is derived from intravenous (IV) studies. Datasets based on oral dosing introduce variability from absorption and first-pass metabolism, which adds noise and complicates the structure-distribution relationship [25].

- Feature Selection: Avoid blindly using all available descriptors. Use filter, wrapper, or embedded methods (e.g., correlation-based feature selection) to identify the most relevant molecular descriptors for distribution, reducing redundancy and improving model accuracy [4].

Comparative Data for ML Tools in Distribution Modeling

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Publicly Available ML Models for Key Distribution Parameters

| Parameter | Model / Platform | Key Features | Performance (Test Set) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) | OCHEM (Consensus Model) | Strict data curation, consensus modeling | R² = 0.91 | [23] |

| Volume of Distribution (VDss) | PKSmart (Random Forest) | Molecular descriptors, fingerprints, & predicted animal PK | External R² = 0.39 | [25] |

| Clearance (CL) | PKSmart (Random Forest) | Molecular descriptors, fingerprints, & predicted animal PK | External R² = 0.46 | [25] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevance to Distribution Modeling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCHEM Platform | Online database & modeling environment | Hosts a state-of-the-art, validated PPB prediction model. | [23] |

| PKSmart Web Application | Open-source PK parameter prediction | Provides freely accessible models for VDss, CL, and other key PK parameters. | [25] |

| RDKit Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source software for cheminformatics | Calculates molecular descriptors (e.g., RDKit descriptors) and fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) essential for feature generation. | [12] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Curated benchmark datasets for ADMET | Provides publicly available, curated datasets for training and benchmarking ML models on ADMET endpoints, including distribution. | [12] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: Building a Robust PPB Prediction Model

This protocol is adapted from state-of-the-art practices for developing a machine learning model to predict Plasma Protein Binding [23] [12].

Data Curation and Cleaning:

- Source: Obtain data from reliable public repositories (e.g., TDC) or in-house assays.

- Standardization: Standardize all molecular structures using a tool like the one by Atkinson et al. [12]. This includes canonicalizing SMILES strings, adjusting tautomers, and removing inorganic salts and organometallic compounds.

- Salt Stripping: For salts, extract the parent organic compound to ensure consistency, as the properties of different salts can vary.

- Deduplication: Remove duplicate entries. If duplicates have inconsistent PPB values, remove the entire group to avoid noise.

Feature Engineering and Selection:

- Generation: Calculate a diverse set of molecular features using software like RDKit. This should include:

- 2D Descriptors: (e.g., RDKit descriptors, Mordred descriptors) representing physicochemical properties.

- Fingerprints: (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) representing molecular substructures.

- Selection: Do not simply concatenate all features. Employ a structured selection process:

- Generation: Calculate a diverse set of molecular features using software like RDKit. This should include:

Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Train multiple algorithms, including Random Forest, XGBoost, and Support Vector Machines.

- Validation Strategy: Use a rigorous nested cross-validation approach. This involves an outer loop for performance estimation and an inner loop for hyperparameter optimization to prevent over-optimistic results.

- Hypothesis Testing: Perform statistical hypothesis testing on cross-validation results to ensure that the performance improvements from different feature sets or models are statistically significant [12].

- Consensus Modeling: Consider building a consensus model that aggregates predictions from multiple top-performing algorithms to enhance robustness and accuracy [23].

Workflow Diagram: ML Model Development for Distribution Parameters

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for developing a machine learning model for predicting distribution parameters like PPB and VDss.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary types of CYP450 inhibition I need to consider in drug development? The three primary types are Reversible Inhibition (including competitive and non-competitive) and Irreversible/Quasi-Irreversible Inhibition, also known as Mechanism-Based Inhibition (MBI) [26].

- Competitive Inhibition: Two substrates compete for the same active site on the enzyme. The substrate with stronger binding affinity (the perpetrator) can displace the one with weaker affinity (the victim), reducing the victim's metabolism and increasing its plasma concentration [26].

- Non-Competitive Inhibition: The inhibitor binds to an allosteric site on the enzyme, spatially separate from the active site. This binding changes the enzyme's 3D structure, rendering the active site inaccessible or non-functional [26].

- Mechanism-Based Inhibition (MBI): The substrate (perpetrator drug) is metabolized by the CYP450 enzyme into a reactive intermediate. This intermediate forms a stable, irreversible complex with the enzyme, permanently inactivating it. This is particularly problematic because the interaction cannot be mitigated by staggering drug administration times [26].

Q2: Can you provide examples of drugs known to be strong CYP450 inhibitors? Yes, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides examples of drugs that interact with CYP enzymes as perpetrators. The following table lists some known strong inhibitors for major CYP isoforms [27].

Table: Examples of Clinically Relevant Strong CYP450 Inhibitors

| Drug/Substance | CYP Isoform Inhibited | Inhibition Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | 2C19 | Strong Inhibitor |

| Fluoxetine | 2C19, 2D6 | Strong Inhibitor |

| Fluvoxamine | 1A2 | Strong Inhibitor |

| Clarithromycin | 3A4 | Strong Inhibitor |

| Bupropion | 2D6 | Strong Inhibitor |

Q3: Why is predicting CYP450 inhibition so critical in early-stage drug discovery? Unfavorable ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties are a major cause of failure in drug development [4]. CYP450 inhibition is a key ADMET endpoint because it can lead to clinically significant drug-drug interactions (DDIs), potentially causing toxic adverse reactions or loss of efficacy [26] [28]. Predicting this inhibition early helps rule out problematic drug candidates, saving significant time and resources [4] [28].

Q4: What are the advantages of using Machine Learning (ML) over traditional methods for predicting CYP inhibition? Traditional experimental methods, while reliable, are resource-intensive and low-throughput [5]. Conventional computational models like QSAR sometimes lack robustness [28]. ML models, particularly advanced deep learning architectures, offer:

- High Efficiency: Ability to perform high-throughput predictions on large compound libraries [5].

- Improved Accuracy: Capability to decipher complex, non-linear structure-property relationships, often outperforming traditional models [5] [28].

- Early Risk Assessment: Enable early screening and prioritization of lead compounds, reducing late-stage attrition [4].

Q5: My ML model for CYP inhibition is performing poorly. What could be wrong? Poor model performance can stem from several issues related to data and methodology [4]:

- Data Quality and Quantity: The model may be trained on a small, noisy, or imbalanced dataset. High-quality, large-scale data is crucial.

- Feature Representation: The molecular descriptors or fingerprints used may not effectively capture the structural features relevant to CYP binding. Exploring different representations (e.g., graph-based, interaction fingerprints) can help [29] [4].

- Data Leakage: The training and test sets may not be properly separated, for example, by not accounting for highly similar compounds that could inflate performance metrics. Using stringent, structure-based data splitting is essential [28].

- Algorithm Selection: The chosen ML algorithm might not be suited to the complexity of the data. Consider exploring more advanced models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or ensemble methods [5] [28].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a Robust Machine Learning Framework for CYP Inhibition Prediction

This protocol outlines the workflow for constructing a high-performance ML model to classify CYP450 inhibitors, synthesizing best practices from recent literature [29] [4] [28].

Table: Key Steps for Building a CYP Inhibition ML Model

| Step | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Collection | Gather labeled bioactivity data from public databases like PubChem BioAssay. | Ensure data comes from consistent experimental protocols to minimize noise. Datasets for major isoforms (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4) are available [28]. |

| 2. Data Curation & Splitting | Preprocess data by standardizing structures, removing duplicates and inorganics. | Use a stringent, structure-based splitting method (e.g., clustering) to create training, validation, and test sets. This prevents data leakage and ensures a true evaluation of generalizability [28]. |

| 3. Feature Engineering | Represent molecules using numerical descriptors. | Options include: • Molecular Descriptors/Fingerprints: Traditional fixed-length vectors [4]. • Protein-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints (PLIF): Derived from molecular docking simulations, providing information on binding mode [29]. • Graph Representations: Atoms as nodes, bonds as edges, suitable for Graph Neural Networks [28]. |

| 4. Model Training & Selection | Train and validate multiple ML algorithms. | Test a range of models: • Classical ML: Random Forest, Support Vector Machines. • Deep Learning (DL): Multi-task Graph Neural Networks (e.g., FP-GNN framework), which can learn from multiple CYP isoforms simultaneously, often yielding superior performance [28]. |

| 5. Model Evaluation | Assess the model on a held-out test set. | Use metrics like Area Under the Curve (AUC), Balanced Accuracy (BA), F1-score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) for a comprehensive view of performance [28]. |

The following workflow diagram visualizes this multi-step process:

Protocol 2: A Multi-Task Deep Learning Approach with FP-GNN

For state-of-the-art predictive performance, consider implementing a multi-task FP-GNN (Fingerprints and Graph Neural Networks) model [28]. This architecture leverages both molecular graph structures and predefined molecular fingerprints.

- Framework: The FP-GNN model concurrently learns from two types of molecular representations:

- Molecular Graph: The molecule is represented as a graph with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges.

- Mixed Molecular Fingerprints: Different types of molecular fingerprints are combined to provide complementary information.

- Multi-Task Learning: A single model is trained to predict inhibition for all five major CYP isoforms simultaneously. This leverages the high sequence homology and structural similarity among CYP binding sites, often leading to better predictive power than training separate models for each isoform [28].

- Performance: This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance, with reported average AUC values of 0.905 across the five major CYP isoforms on external test sets [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key resources for conducting computational research on CYP450 inhibition.