A Practical Guide to QSAR Model Validation: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of validating Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models to ensure reliable predictions in drug discovery and chemical safety assessment.

A Practical Guide to QSAR Model Validation: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of validating Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models to ensure reliable predictions in drug discovery and chemical safety assessment. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore foundational validation concepts, implement advanced methodological approaches like double cross-validation, troubleshoot common pitfalls including model uncertainty and data quality issues, and provide comparative analysis of validation criteria. The article synthesizes current best practices from recent research (2021-2025) and regulatory perspectives, offering practical frameworks for building robust, predictive QSAR models that meet contemporary scientific and regulatory standards across pharmaceutical, environmental, and cosmetic applications.

Understanding QSAR Validation: Why Robust Model Assessment is Non-Negotiable

In modern drug discovery and chemical safety assessment, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has evolved from a niche computational tool to an indispensable methodology. At its core, QSAR is a computational technique that predicts a compound's biological activity or properties based on its molecular structure using numerical descriptors of features like hydrophobicity, electronic properties, and steric factors [1]. While regulatory frameworks provide essential guidance for QSAR applications, truly reliable models must transcend mere compliance checkboxes. Comprehensive validation represents the critical bridge between theoretical predictions and scientifically defensible conclusions, ensuring models deliver accurate, reproducible, and meaningful results across diverse applications—from lead optimization in drug discovery to hazard assessment of environmental contaminants.

The validation paradigm extends beyond simple statistical metrics to encompass the entire model lifecycle, including data quality assessment, model construction, performance evaluation, and definition of applicability domains. This multifaceted approach ensures that QSAR predictions can be trusted for critical decision-making, particularly when experimental data is scarce or expensive to obtain. As the field advances with increasingly complex machine learning algorithms and larger datasets, robust validation practices become even more crucial for separating scientific insight from statistical artifact.

Methodological Framework: Beyond Basic Validation

Foundational Components of QSAR Modeling

Developing a reliable QSAR model requires meticulous attention to multiple interconnected components, each contributing to the model's predictive power and reliability. The process begins with data selection and quality, where datasets must include sufficient compounds (typically at least 20) tested under uniform biological conditions with well-defined activities [1]. Descriptor generation follows, capturing molecular features across multiple dimensions—from simple molecular weight (0D) to 3D conformations and time-dependent variables (4D), including hydrophobic constants (π), Hammett constants (σ), and steric parameters (Es, MR) [1]. Variable selection techniques like stepwise regression, genetic algorithms, or simulated annealing then isolate the most relevant descriptors, preventing model overfitting [1].

The core model building phase employs statistical methods tailored to the data type—regression for numerical data, discriminant analysis or decision trees for classification [1]. Finally, comprehensive validation ensures model robustness through both internal (cross-validation) and external (hold-out set) methods [1] [2]. This multi-stage process demands scientific rigor at each step, as weaknesses in any component compromise the entire model's predictive capability and regulatory acceptance.

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Validation Methods

| Validation Method | Key Parameters | Acceptance Threshold | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golbraikh & Tropsha [2] | r², K, K', (\frac{{\text{r}}^{2}-{\text{r}}_{0}^{2}}{{\text{r}}^{2}}) | r² > 0.6, 0.85 < K < 1.15, (\frac{{\text{r}}^{2}-{\text{r}}_{0}^{2}}{{\text{r}}^{2}}) < 0.1 | Comprehensive regression-based assessment | Multiple criteria must be simultaneously satisfied |

| Roy (RTO) [2] | (\ r_{m}^{2} ) | (\ r_{m}^{2} ) > 0.5 | Specifically designed for QSAR validation | Sensitive to calculation method for (\ r_{0}^{2} ) |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) [2] | CCC | CCC > 0.8 | Measures agreement between predicted and observed values | Does not assess bias or precision separately |

| Roy (Training Range) [2] | AAE, SD, training set range | AAE ≤ 0.1 × training set range and AAE + 3×SD ≤ 0.2 × training set range | Contextualizes error relative to data variability | Highly dependent on training set composition |

| Statistical Significance Testing [2] | Model errors for training and test sets | No significant difference between errors | Direct comparison of model performance | Requires careful experimental design |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Implementing a comprehensive validation strategy requires systematic experimental protocols. For external validation, data splitting should employ sphere exclusion or clustering methods to ensure balanced chemical diversity across training and test sets, thereby improving the model's applicability domain [1]. The test set should typically contain 20-30% of the total compounds and represent the chemical space of the training set.

For regression models, calculate all parameters from the comparative table using the test set predictions versus experimental values. The coefficient of determination (r²) alone is insufficient to indicate validity [2]. Researchers must also verify that slopes of regression lines through origin (K, K') fall within acceptable ranges and compute the (\ r_{m}^{2} ) metric to evaluate predictive potential.

For classification models, particularly with imbalanced datasets common in virtual screening, move beyond balanced accuracy to prioritize Positive Predictive Value (PPV). This shift recognizes that in practical applications like high-throughput virtual screening, the critical need is minimizing false positives among the top-ranked compounds rather than globally balancing sensitivity and specificity [3]. Calculate PPV for the top N predictions corresponding to experimental throughput constraints (e.g., 128 compounds for a standard plate), as this directly measures expected hit rates in real-world scenarios.

The applicability domain must be explicitly defined using approaches like leverage methods, distance-based methods, or range-based methods. This determines the boundaries within which the model can provide reliable predictions and is essential for regulatory acceptance under OECD principles [4].

Case Study: Validated QSAR-PBPK Modeling of Fentanyl Analogs

Experimental Workflow and Implementation

A recent innovative application of rigorously validated QSAR modeling demonstrates its power in addressing public health emergencies. Researchers developed a QSAR-integrated Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) framework to predict human pharmacokinetics for 34 fentanyl analogs—emerging new psychoactive substances with scarce experimental data [5] [6]. The validation workflow followed a meticulous multi-stage process:

First, the team developed a PBPK model for intravenous β-hydroxythiofentanyl in Sprague-Dawley rats using QSAR-predicted tissue/blood partition coefficients (Kp) via the Lukacova method in GastroPlus software [5]. They compared predicted pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC₀–t, Vss, T₁/₂) against experimental values obtained through LC-MS/MS analysis of plasma samples collected at eight time points following 7 μg/kg intravenous administration [5].

Next, they compared the accuracy of different parameter sources by building separate human fentanyl PBPK models using literature in vitro data, QSAR predictions, and interspecies extrapolation [5]. This direct comparison quantified the performance improvement achieved through QSAR integration.

Finally, the validated framework was applied to predict plasma and tissue distribution (including 10 organs) for 34 human fentanyl analogs, identifying eight compounds with brain/plasma ratio >1.2 (compared to fentanyl's 1.0), indicating higher CNS penetration and abuse risk [5] [6].

Validation Results and Performance Metrics

The rigorous validation protocol yielded compelling evidence for the QSAR-PBPK framework's predictive power. For β-hydroxythiofentanyl, all predicted rat pharmacokinetic parameters fell within a 2-fold range of experimental values, demonstrating exceptional accuracy for a novel compound [5]. In human fentanyl models, QSAR-predicted Kp substantially improved accuracy compared to traditional approaches—Vss error reduced from >3-fold with interspecies extrapolation to <1.5-fold with QSAR prediction [5].

For structurally similar, clinically characterized analogs like sufentanil and alfentanil, predictions of key PK parameters (T₁/₂, Vss) fell within 1.3–1.7-fold of clinical data, confirming the framework's utility for generating testable hypotheses about pharmacokinetics of understudied analogs [6]. This validation against known compounds provided the scientific foundation to trust predictions for truly novel substances lacking any experimental data.

Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR-PBPK Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Platform | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR Modeling | ADMET Predictor v.10.4.0.0 (Simulations Plus) | Prediction of physicochemical and PK properties | Generating molecular descriptors and predicting parameters like logD, pKa, Fup [5] |

| PBPK Modeling | GastroPlus v.9.8.3 (Simulations Plus) | PBPK modeling and simulation | Integrating QSAR-predicted parameters to build and simulate PBPK models [5] |

| Pharmacokinetic Analysis | Phoenix WinNonlin v.8.3 | PK parameter estimation | Non-compartmental analysis of experimental data for model validation [5] |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem Database | Structural information source | Obtaining structural formulas of fentanyl analogs for descriptor calculation [5] |

| Data Analysis | SPSS Software | Statistical analysis and r² calculation | Computing validation parameters and statistical significance [2] |

Paradigm Shift: Rethinking Validation Metrics for Modern Applications

The Limitations of Traditional Validation Approaches

Traditional QSAR validation has emphasized balanced accuracy and dataset balancing as gold standards, particularly for classification models. However, these approaches show significant limitations when applied to contemporary challenges like virtual screening of ultra-large chemical libraries. Balanced accuracy aims for models that equally well predict both positive and negative classes across the entire external set, which often doesn't align with practical screening objectives where only a small fraction of top-ranked compounds can be experimentally tested [3].

The common practice of balancing training sets through undersampling the majority class, while improving balanced accuracy, typically reduces Positive Predictive Value (PPV)—precisely the metric most critical for virtual screening success [3]. This fundamental mismatch between traditional validation metrics and real-world application needs has driven a paradigm shift in thinking about what constitutes truly valid and useful QSAR models.

Positive Predictive Value as a Key Metric for Virtual Screening

In modern drug discovery contexts where QSAR models screen ultra-large libraries (often containing billions of compounds) but experimental validation is limited to small batches (typically 128 compounds per plate), PPV emerges as the most relevant validation metric. PPV directly measures the proportion of true actives among compounds predicted as active, perfectly aligning with the practical goal of maximizing hit rates within limited experimental capacity [3].

Comparative studies demonstrate that models trained on imbalanced datasets with optimized PPV achieve hit rates at least 30% higher than models trained on balanced datasets with optimized balanced accuracy [3]. This performance difference has substantial practical implications—for a screening campaign selecting 128 compounds, the PPV-optimized approach could yield approximately 38 more true hits than traditional approaches, dramatically accelerating discovery while conserving resources.

Strategic Implementation of PPV-Focused Validation

Implementing PPV-focused validation requires methodological adjustments. Rather than calculating PPV across all predictions, researchers should compute it specifically for the top N rankings corresponding to experimental constraints (e.g., top 128, 256, or 512 compounds) [3]. This localized PPV measurement directly reflects expected experimental hit rates. Additionally, while AUROC and BEDROC metrics offer value, their complexity and parameter sensitivity make them less interpretable than the straightforward PPV for assessing virtual screening utility [3].

This paradigm shift doesn't discard traditional validation but rather contextualizes it—models must still demonstrate statistical robustness and define applicability domains, but ultimate metric selection should align with the specific context of use. For regulatory applications focused on hazard identification, sensitivity might remain prioritized; for drug discovery virtual screening, PPV becomes paramount.

The critical role of validation in QSAR modeling extends far beyond regulatory compliance to encompass scientific rigor, predictive reliability, and practical utility. As demonstrated by the QSAR-PBPK framework for fentanyl analogs, comprehensive validation enables confident application of computational models to pressing public health challenges where experimental data is scarce. The evolving understanding of validation metrics—particularly the shift toward PPV for virtual screening applications—reflects the field's maturation toward context-driven validation strategies.

Future advances will likely continue this trajectory, with validation frameworks incorporating increasingly sophisticated assessment of model uncertainty, applicability domain definition, and context-specific performance metrics. By embracing these comprehensive validation approaches, researchers can ensure their QSAR models deliver not just regulatory compliance, but genuine scientific insight and predictive power across the diverse landscape of drug discovery, toxicology assessment, and chemical safety evaluation.

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, validation is not merely a recommended best practice—it is the cornerstone of developing reliable, predictive, and regulatory-acceptable models. Validation ensures that a mathematical relationship derived from a set of chemicals can make accurate and trustworthy predictions for new, unseen compounds. This process is rigorously divided into two fundamental pillars: internal and external validation. Adherence to these principles is critical for applying QSAR models in drug discovery and chemical risk assessment, directly impacting decisions that can accelerate therapeutic development or safeguard public health [7] [8].

The core distinction lies in the data used for evaluation. Internal validation assesses the model's stability and predictive performance within the confines of the dataset used to build it. In contrast, external validation is the ultimate test of a model's real-world utility, evaluating its ability to generalize to a completely independent dataset that was not involved in the model-building process [7].

Internal vs. External Validation: A Conceptual and Practical Comparison

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, purposes, and common techniques associated with internal and external validation.

| Feature | Internal Validation | External Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Purpose | To assess the model's internal stability and predictiveness and to mitigate overfitting [9] [7]. | To evaluate the model's generalizability and real-world predictive ability on unseen data [2] [7]. |

| Data Used | Only the training set (the data used to build the model) [7]. | A separate, independent test set that is never used during model development or internal validation [2] [9]. |

| Key Principle | "How well does the model explain the data it was trained on?" | "How well can the model predict data it has never seen before?" |

| Common Techniques | - Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: Iteratively removing one compound, training the model on the rest, and predicting the left-out compound [9] [7].- k-Fold Cross-Validation: Splitting the training data into 'k' subsets and repeating the train-and-test process 'k' times [9]. | Test Set Validation: A one-time hold-out method where a portion (e.g., 20-30%) of the original data is reserved from the start solely for final testing [9] [7]. |

| Key Metrics | - Q² (Q²({}{\text{LOO}}), Q²({}{\text{k-fold}})) - the cross-validated correlation coefficient [10].- RSR({}_{\text{CV}}) - the cross-validated Root Mean Square Error [10]. | - Q²({}{\text{EXT}}) or R²({}{\text{ext}}) - the coefficient of determination for the test set [10].- Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) > 0.8 is a marker of a valid model [2].- r²({}_{\text{m}}) metric and Golbraikh and Tropsha criteria [2]. |

| Role in Validation | A necessary first step to check model robustness during development. It provides an initial, but often optimistic, performance estimate [7]. | The definitive and mandatory step for confirming model reliability for regulatory purposes and external prediction [7]. |

A critical insight from recent studies is that a high coefficient of determination (r²) from the model fitting alone is insufficient to prove a model's validity [2]. A model might perfectly fit its training data but fail miserably on new compounds—a phenomenon known as overfitting. This is why external validation is indispensable. As established in foundational principles, "only models that have been validated externally, after their internal validation, can be considered reliable and applicable for both external prediction and regulatory purposes" [7].

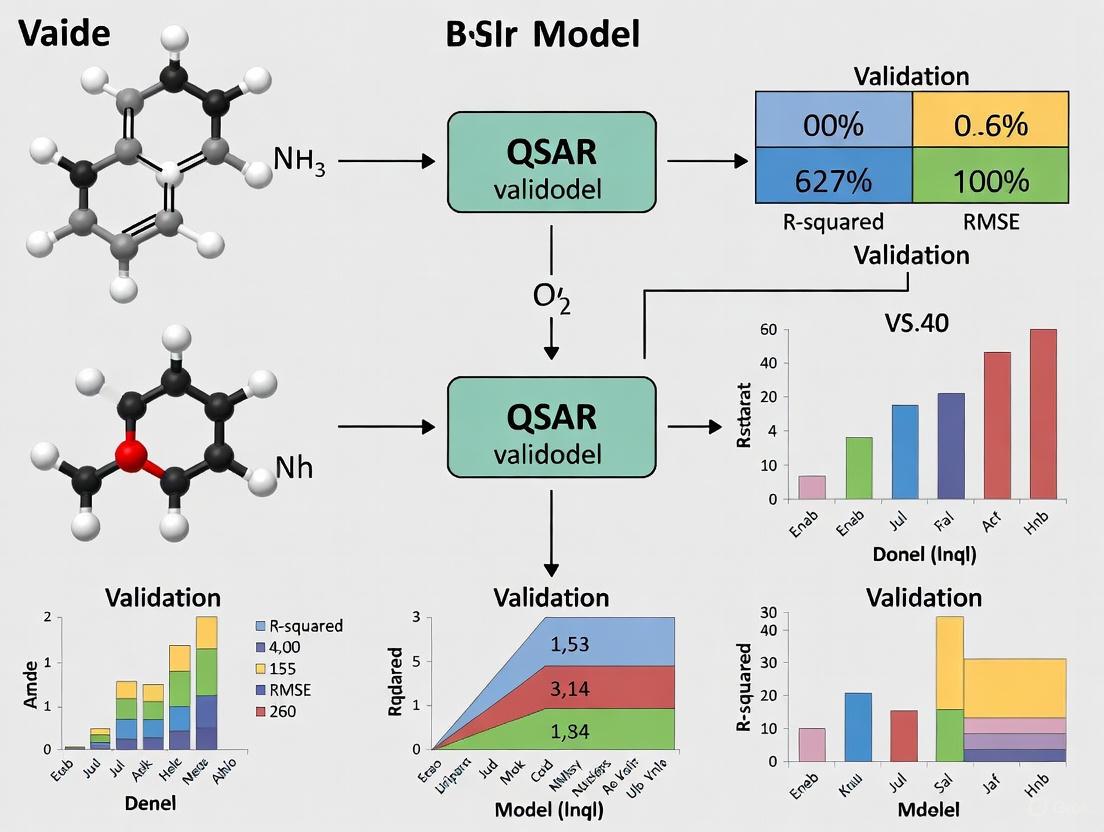

Visualizing the QSAR Validation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the standard QSAR modeling workflow, highlighting the distinct roles of internal and external validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Internal Validation via k-Fold Cross-Validation

This protocol is a standard procedure to assess model robustness during development [9] [10].

- Model Training: Begin with a fully developed QSAR model using the entire training set.

- Data Partitioning: Randomly split the training set into 'k' approximately equal-sized subsets (folds). A common value for k is 5 or 10.

- Iterative Training and Prediction: For each of the k folds:

- Temporarily set aside one fold to serve as a temporary validation set.

- Train the QSAR model on the remaining k-1 folds.

- Use the newly trained model to predict the biological activity of the compounds in the held-out fold.

- Store the predicted values for all compounds in this fold.

- Performance Calculation: After cycling through all k folds, every compound in the training set has received a cross-validated prediction. Calculate internal validation metrics like Q² and RSR({}_{\text{CV}}) by comparing these predicted values to the actual experimental values.

- Interpretation: A high Q² value (e.g., > 0.6 or 0.7) indicates a model with good internal predictive stability and a low risk of overfitting.

Protocol 2: External Validation with an Independent Test Set

This protocol is the critical final step for establishing a model's utility for prediction [2] [7] [10].

- Initial Data Separation: Before any model development begins, randomly select a portion of the full dataset (commonly 20-30%) to be set aside as the external test set. This set must be kept completely separate and must not be used for any aspect of model building or descriptor selection.

- Model Building: Use the remaining 70-80% of the data (the training set) to develop the QSAR model, including all steps of descriptor calculation, feature selection, and algorithm training. Internal validation (e.g., k-fold CV) is performed on this training set to optimize the model.

- Final Prediction: Apply the final, fully-trained model to the hitherto untouched external test set. The model generates predicted activity values for these compounds based solely on their structures.

- Comprehensive Metrics Calculation: Calculate a suite of external validation metrics by comparing the predictions to the experimental values for the test set. Key metrics include:

- Q²({}_{\text{EXT}}): The coefficient of determination for the test set. A value above 0.5 is generally considered acceptable, and above 0.6 is good [10].

- Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC): Measures both precision and accuracy relative to the line of unity. A CCC > 0.8 indicates a valid model [2].

- Golbraikh and Tropsha Criteria: A set of conditions involving slopes of regression lines and differences between determination coefficients, which, if passed, strongly support model validity [2].

- Applicability Domain (AD) Assessment: Evaluate whether the compounds in the external test set fall within the chemical space of the training set (the model's Applicability Domain). Predictions for compounds outside the AD are considered less reliable [11] [7].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

The following table lists key computational tools and resources essential for implementing rigorous QSAR validation protocols.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| KNIME [12] [13] | Open-Source Platform | Provides a visual, workflow-based environment for building, automating, and validating QSAR models. Integrates various machine learning algorithms and data processing nodes. |

| PyQSAR [10] | Open-Source Python Library/Tool | Offers built-in tools for descriptor selection and QSAR model construction, facilitating the entire model development and validation pipeline. |

| OCHEM [10] | Web-Based Platform | Calculates a vast array of molecular descriptors (1D, 2D, 3D) necessary for model building. |

| RDKit [13] [12] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Used for chemical informatics, descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, and integration into larger workflows in Python or KNIME. |

| Mordred [14] | Python Package | Calculates a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors for large datasets, supporting model parameterization. |

| alvaDesc [12] | Commercial Software | Calculates a wide range of molecular descriptors from several families (constitutional, topological, etc.) for model development. |

| Scikit-learn [13] | Open-Source Python Library | Provides a vast collection of machine learning algorithms and tools for cross-validation, hyperparameter tuning, and metric calculation. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) Tools [11] [12] | Methodological Framework | Methods like Isometric Stratified Ensemble (ISE) mapping are used to define the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable, a critical part of external validation reporting. |

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery and toxicology, enabling the prediction of chemical bioactivity from molecular structures. The reliability of any QSAR model, however, is intrinsically linked to the comprehensive assessment and quantification of its predictive uncertainty. Model uncertainty in QSAR refers to the confidence level associated with model predictions and arises from multiple sources throughout the model development pipeline. As noted by De et al., the reliability of any QSAR model depends on multiple aspects including "the accuracy of the input dataset, selection of significant descriptors, the appropriate splitting process of the dataset, statistical tools used, and most notably on the measures of validation" [15] [16]. Without proper uncertainty quantification, QSAR predictions may lead to costly missteps in experimental follow-up, particularly in high-stakes applications like drug design and regulatory toxicology.

The implications of unaddressed uncertainty extend beyond academic concerns to practical decision-making in virtual screening and safety assessment. As one study notes, "Predictions for compounds outside the application domain will be thought to be less reliable (corresponding to higher uncertainty), and vice versa" [17]. This review systematically examines the sources of QSAR model uncertainty, compares state-of-the-art quantification methodologies, evaluates experimental validation protocols, and discusses implications for predictive reliability within the broader context of QSAR validation research.

Uncertainty in QSAR modeling originates from multiple stages of model development and application. A comprehensive analysis reveals that these uncertainties can be systematically categorized into distinct sources, with some being frequently expressed implicitly rather than explicitly in scientific literature [18].

Classification by Origin and Nature

Uncertainty in QSAR predictions can be fundamentally divided into three primary categories based on their origin and nature:

Epistemic Uncertainty: Derived from the Greek word episteme (knowledge), this uncertainty results from insufficient knowledge or data in certain regions of the chemical space [17]. It manifests when models encounter compounds structurally dissimilar to those in the training set. As depicted in Figure 1, epistemic uncertainty is higher in chemical regions with sparse training data. Unlike other uncertainty types, epistemic uncertainty can be reduced by collecting additional relevant data in the underrepresented regions [17].

Aleatoric Uncertainty: Stemming from the Latin alea (dice), this uncertainty represents the inherent noise or randomness in the experimental data used for model training [17]. This includes variations from systematic and random errors in biological assays and measurement systems. As an intrinsic property of the data, aleatoric uncertainty cannot be reduced by collecting more training samples and often represents the minimal achievable prediction error for a given endpoint [17].

Approximation Uncertainty: This category encompasses errors arising from model inadequacy—when simplistic models attempt to capture complex structure-activity relationships [17]. While theoretically significant, approximation uncertainty is often considered negligible when using flexible deep learning architectures that serve as universal approximators.

Empirical Analysis of Uncertainty Expression

A recent analysis of uncertainty expression in QSAR studies focusing on neurotoxicity revealed important patterns in how uncertainties are communicated in scientific literature. The study identified implicit and explicit uncertainty indicators and categorized them according to 20 potential uncertainty sources [18]. The findings demonstrated that:

- Implicit uncertainty was more frequently expressed (64% of instances) across most uncertainty sources (13 out of 20 categories) [18] [19].

- Explicit uncertainty was dominant in only three uncertainty sources, indicating that researchers predominantly communicate uncertainty through indirect language rather than quantitative statements [18].

- The most frequently cited uncertainty sources included Mechanistic plausibility, Model relevance, and Model performance, suggesting these areas represent primary concerns for QSAR practitioners [18].

- Notable gaps were observed, with some recognized uncertainty sources like Data balance rarely mentioned despite their established importance in the broader QSAR literature [18] [3].

Table 1: Frequency of Uncertainty Expression in QSAR Studies

| Uncertainty Category | Expression Frequency | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Implicit Uncertainty | 64% | Mechanistic plausibility, Model relevance, Model performance |

| Explicit Uncertainty | 36% | Data quality, Experimental validation, Statistical measures |

| Unmentioned Sources | - | Data balance, Representation completeness |

Methodologies for Uncertainty Quantification

Multiple methodological frameworks have been developed to address the challenge of uncertainty quantification in QSAR modeling, each with distinct theoretical foundations and implementation considerations.

Primary Uncertainty Quantification Approaches

Similarity-Based Approaches: These methods, rooted in the traditional concept of Applicability Domain (AD), operate on the principle that "if a test sample is too dissimilar to training samples, the corresponding prediction is likely to be unreliable" [17]. Techniques range from simple bounding boxes and convex hull approaches in chemical descriptor space to more sophisticated distance metrics such as the STD2 and SDC scores [17] [20]. These methods are inherently input-oriented, focusing on the position of query compounds relative to the training set chemical space without explicitly considering model architecture.

Bayesian Approaches: These methods treat model parameters and predictions as probability distributions rather than point estimates [17] [20]. Through Bayesian inference, these approaches naturally incorporate uncertainty by calculating posterior distributions of model weights. The total uncertainty in Bayesian frameworks can be decomposed into aleatoric (data noise) and epistemic (model knowledge) components, providing insight into uncertainty sources [20]. Bayesian neural networks and Gaussian processes represent prominent implementations in QSAR contexts.

Ensemble-Based Approaches: These techniques leverage the consensus or disagreement among multiple models to estimate prediction uncertainty [17]. Bootstrapping methods, which create multiple models through resampling with replacement, belong to this category [21]. The variance in predictions across ensemble members serves as a proxy for uncertainty, with higher variance indicating less reliable predictions. As noted by Scalia et al., ensemble methods consistently demonstrate robust performance across various uncertainty quantification tasks [17].

Hybrid Frameworks: Recognizing the complementary strengths of different approaches, recent research has investigated consensus strategies that combine distance-based and Bayesian methods [20]. These hybrid frameworks aim to mitigate the limitations of individual approaches—specifically, the overconfidence of Bayesian methods for out-of-distribution samples and the ambiguous threshold definitions of similarity-based methods [20]. One study demonstrated that such hybrid models "robustly enhance the model ability of ranking absolute errors" and produce better-calibrated uncertainty estimates [20].

Comparative Analysis of Uncertainty Quantification Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Uncertainty Quantification Methodologies in QSAR

| Method Category | Theoretical Basis | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Based | Applicability Domain concept | Intuitive interpretation; Computationally efficient | Ambiguous distance thresholds; Lacks data noise information | Virtual screening; Toxicity prediction [17] |

| Bayesian | Probability theory; Bayes' theorem | Theoretical rigor; Uncertainty decomposition | Computationally intensive; Tendency for overconfidence | Molecular property prediction; Protein-ligand interaction [17] [20] |

| Ensemble-Based | Collective intelligence; Variance analysis | Simple implementation; Model-agnostic | Computationally expensive; Multiple models required | Bioactivity prediction; Material property estimation [17] [21] |

| Hybrid | Consensus principle; Complementary strengths | Improved error ranking; Robust performance | Increased complexity; Implementation challenges | QSAR regression modeling; Domain shift scenarios [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Uncertainty Validation

Rigorous experimental validation is essential for assessing the performance of uncertainty quantification methods in practical QSAR applications.

Benchmarking Framework and Metrics

A comprehensive validation protocol for uncertainty quantification methods should address both ranking ability and calibration ability:

Ranking Ability Assessment: This evaluates how well the uncertainty estimates correlate with prediction errors. For regression tasks, the Spearman correlation coefficient between absolute errors and uncertainty values is commonly used [17]. For classification tasks, the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (auROC) or Precision-Recall curve (auPRC) can quantify how effectively uncertainty prioritizes misclassified samples [17].

Calibration Ability Evaluation: This measures how accurately the uncertainty estimates reflect the actual error distribution. In regression settings, well-calibrated uncertainty should enable accurate confidence interval estimation—for instance, 95% of predictions should fall within approximately two standard deviations of the true value for normally distributed errors [17] [20].

The experimental workflow typically involves partitioning datasets into training, validation, and test sets, with the validation set potentially used for post-hoc calibration of uncertainty estimates [20].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for validating uncertainty quantification methods in QSAR modeling.

Case Study: Hybrid Framework Evaluation

A recent study exemplifying rigorous uncertainty validation developed a hybrid framework combining distance-based and Bayesian approaches for QSAR regression modeling [20]. The experimental protocol included:

- Dataset Preparation: 24 bioactivity datasets were used, each partitioned into active training, passive training, calibration, and validation sets to ensure robust evaluation [20].

- Model Implementation: Deep learning-based QSAR models were trained with early stopping on the validation set to prevent overfitting [20].

- Uncertainty Combination: Multiple consensus strategies were investigated to integrate distance-based and Bayesian uncertainty estimates, including weighted averages and more complex fusion algorithms [20].

- Performance Benchmarking: The hybrid approach was quantitatively compared against individual methods using both ranking and calibration metrics in both in-domain and domain-shift settings [20].

The results demonstrated that the hybrid framework "robustly enhance the model ability of ranking absolute errors" and produced better-calibrated uncertainty estimates compared to individual methods, particularly in domain shift scenarios where test compounds differed substantially from training molecules [20].

Implications for Predictive Reliability and Virtual Screening

The accurate quantification of model uncertainty has profound implications for the practical utility of QSAR predictions in decision-making processes, particularly in virtual screening campaigns.

Performance Metrics Re-evaluation

Traditional QSAR best practices have emphasized balanced accuracy as the primary metric for classification models, often recommending dataset balancing through undersampling of majority classes [3]. However, this approach requires reconsideration in the context of virtual screening of modern ultra-large chemical libraries, where the practical objective is identifying a small number of hit compounds from millions of candidates [3].

- Positive Predictive Value Emphasis: For virtual screening applications, the Positive Predictive Value becomes a more relevant metric than balanced accuracy [3]. PPV directly measures the proportion of true actives among compounds predicted as active, aligning with the practical goal of maximizing hit rates in experimental validation.

- Imbalanced Dataset Utilization: Studies demonstrate that models trained on imbalanced datasets—reflecting the natural prevalence of inactive compounds in chemical space—can achieve at least 30% higher hit rates in the top predictions compared to models trained on balanced datasets [3].

- Early Enrichment Focus: Metrics that emphasize "high early enrichment" of actives among the highest-ranked predictions, such as BEDROC (Boltzmann-Enhanced Discrimination of ROC) or PPV calculated specifically for the top N predictions, provide more meaningful assessments of virtual screening utility [3].

Table 3: Impact of Uncertainty Awareness on Virtual Screening Outcomes

| Screening Approach | Key Metrics | Hit Rate Performance | Practical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Balanced Models | Balanced Accuracy | Lower hit rates in top candidates | Suboptimal for experimental follow-up |

| Uncertainty-Aware Imbalanced Models | Positive Predictive Value | 30% higher hit rates | Better aligned with experimental constraints |

| Uncertainty-Guided Screening | PPV in top N predictions | Maximized early enrichment | Optimal for plate-based experimental design |

Uncertainty-Informed Decision Framework

The integration of uncertainty quantification enables more sophisticated decision frameworks for virtual screening:

- Risk-Based Compound Prioritization: Predictions can be categorized based on both predicted activity and associated uncertainty, allowing researchers to balance potential reward (high activity) against risk (high uncertainty) [15] [16]. Tools like the Prediction Reliability Indicator use composite scoring to classify query compounds as 'good', 'moderate', or 'bad' predictions, providing actionable guidance for experimental design [15].

- Consensus Prediction Strategies: 'Intelligent' selection of multiple models with consensus predictions has been shown to improve external predictivity compared to individual models [15] [16] [19]. One study reported that consensus methods produced higher over-prediction rates (39% vs 24-25% for individual models) while reducing under-prediction rates (8% vs 10-20%), resulting in more conservative and potentially safer predictions for regulatory applications [19].

- Resource Allocation Optimization: By identifying predictions with high uncertainty, researchers can prioritize experimental verification for these compounds or allocate resources for additional data generation in uncertain chemical regions, implementing active learning strategies [17].

Figure 2: Uncertainty-informed decision framework for virtual screening and experimental validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental implementation of uncertainty quantification in QSAR modeling relies on specialized software tools and computational resources.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for QSAR Uncertainty Quantification

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Validation Suites | DTCLab Software Tools | Double cross-validation; Prediction Reliability Indicator; Small dataset modeling | Freely available [15] [16] |

| Bayesian Modeling Frameworks | Bayesian Neural Networks; Gaussian Processes | Probabilistic prediction with uncertainty decomposition | Various open-source implementations [17] [20] |

| Similarity Calculation Tools | Box Bounding; Convex Hull; STD2; SDC score | Applicability domain definition and similarity assessment | Custom implementation required [17] |

| Ensemble Modeling Platforms | Bootstrapping implementations; Random Forest | Multiple model generation and consensus prediction | Standard machine learning libraries [17] [21] |

| Hybrid Framework Implementations | Custom consensus strategies | Combining distance-based and Bayesian uncertainties | Research code [20] |

| QSPR/QSAR Development Software | CORAL-2023 | Monte Carlo optimization with correlation weight descriptors | Freely available [22] |

The comprehensive assessment of model uncertainty represents a critical component of QSAR validation frameworks, directly impacting the reliability and regulatory acceptance of computational predictions. This review has systematically examined the multifaceted nature of uncertainty in QSAR modeling, from its fundamental sources to advanced quantification methodologies and validation protocols. The evidence consistently demonstrates that uncertainty-aware QSAR approaches—particularly hybrid frameworks combining complementary quantification methods—provide more reliable and actionable predictions for drug discovery and safety assessment.

The implications extend beyond technical considerations to practical decision-making in virtual screening, where uncertainty quantification enables risk-based compound prioritization and resource optimization. As the field progresses toward increasingly complex models and applications, the integration of robust uncertainty quantification will be essential for building trustworthy QSAR frameworks that earn regulatory confidence and effectively guide experimental efforts. Future research directions should address current limitations in uncertainty calibration, develop standardized benchmarking protocols, and improve the explicit communication of uncertainty in QSAR reporting practices.

This guide provides an objective comparison of core concepts essential for the validation of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, framing them within the broader thesis of ensuring reliable predictions in drug development and computational toxicology.

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Validation Concepts

The table below defines and contrasts the three key validation terminologies.

| Term | Core Definition & Purpose | Primary Causes & Manifestations | Common Estimation/Evaluation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Errors [23] [24] | Quantifies the difference between a model's predictions and observed values. Used to assess a model's predictive performance and generalization error on new data. [23] | • Experimental noise in training/test data. [24]• Model overfitting or underfitting.• Extrapolation outside the model's Applicability Domain (AD). [25] | • Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [24]• Coefficient of Determination (R²) [2]• Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) [2]• Double Cross-Validation [23] |

| Applicability Domain (AD) [26] [27] | The chemical space defined by the model's training compounds and model algorithm. Predictions are reliable only for query compounds structurally similar to this space. [26] | • Query compound is structurally dissimilar from training set. [26]• Query compound has descriptor values outside the training set range. [26] | • Range-Based (e.g., Bounding Box) [26]• Distance-Based (e.g., Euclidean, Mahalanobis) [26]• Geometric (e.g., Convex Hull) [26]• Leverage [26]• Tanimoto Distance on fingerprints [25] |

| Model Selection Bias [23] | An optimistic bias in prediction error estimates caused when the same data is used for both model selection (e.g., variable selection) and model assessment. [23] | • Lacking independence between validation data and the model selection process. [23]• Selecting overly complex models that adapt to noise in the data. [23] | • Double (Nested) Cross-Validation: Uses an outer loop for model assessment and an inner loop for model selection to ensure independence. [23]• Hold-out Test Set: A single, blinded test set not involved in any model building steps. [23] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the validity of QSAR models, researchers employ specific experimental protocols. The following workflows detail the standard methodologies for two critical processes: external validation and double cross-validation.

Protocol 1: External Validation via Data Splitting

This is a standard protocol for evaluating the predictive performance of a final, fixed model [2] [28].

- Data Collection & Curation: Collect a dataset of compounds with experimentally measured biological activities or properties. Ensure data quality and consistency [2] [28].

- Descriptor Calculation & Processing: Generate molecular descriptors or fingerprints for all compounds. Apply preprocessing such as scaling and dimensionality reduction if needed [26].

- Data Splitting: Randomly divide the dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) and a test set (20-30%). More advanced splitting strategies, such as scaffold-based splitting, can be used to assess performance on structurally novel compounds [25] [28].

- Model Training: Use only the training set to build (train) the QSAR model using the chosen algorithm (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) [2].

- Model Prediction & Validation:

- Apply the finalized model to predict the activities of the test set compounds.

- Calculate prediction errors (e.g., RMSE, R²) by comparing the predictions to the experimental values of the test set [2].

- Evaluate the Applicability Domain for each test set prediction to determine if the error is associated with extrapolation [26] [25].

Protocol 2: Double Cross-Validation for Error Estimation and Model Selection

This protocol provides a robust framework for both selecting the best model and reliably estimating its prediction error without a separate hold-out test set [23].

- Outer Loop (Model Assessment):

- Split the entire dataset into ( k ) folds (e.g., 5 or 10).

- For each fold ( i ):

- Hold out fold ( i ) as the test set.

- Use the remaining ( k-1 ) folds as the training set for the inner loop.

- Inner Loop (Model Selection on the Training Set):

- Take the ( k-1 ) folds from the outer loop and perform another ( k )-fold cross-validation.

- For each configuration of model hyperparameters (e.g., number of variables, neural network architecture):

- Train the model and estimate its performance via internal cross-validation.

- Select the best-performing model configuration (hyperparameters) based on the lowest cross-validated error from this inner loop.

- Final Assessment in the Outer Loop:

- Train a new model on the entire ( k-1 ) training folds using the selected best configuration.

- Apply this model to the held-out outer test set (fold ( i )) to obtain a prediction error.

- This error is recorded as an unbiased estimate because the test data was not involved in the model selection process [23].

- Averaging: Repeat the process for all ( k ) outer folds. The average prediction error across all outer test folds provides a reliable estimate of the model's generalization error [23].

The following diagram illustrates the logical structure and data flow of the Double Cross-Validation protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential computational tools and their functions for conducting rigorous QSAR validation studies.

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function | Relevance to Validation |

|---|---|---|

| ProQSAR [29] | A modular, reproducible workbench for end-to-end QSAR development. | Integrates conformal calibration for uncertainty quantification and applicability-domain diagnostics for risk-aware predictions. [29] |

| VEGA Platform [11] | A software platform hosting multiple (Q)SAR models for toxicological and environmental endpoints. | Widely used for regulatory purposes; its models include well-defined Applicability Domain assessments for each prediction. [11] |

| EPI Suite [11] | A widely used software suite for predicting physical/chemical properties and environmental fate. | Often used in comparative performance studies; its predictions are evaluated against defined ADs for reliability. [11] |

| MATLAB / Python (scikit-learn) [26] [23] | High-level programming languages and libraries for numerical computation and machine learning. | Enable the custom implementation of double cross-validation, various AD methods, and advanced error-estimation techniques. [26] [23] |

| Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [30] | A non-parametric method to estimate the probability density function of a random variable. | A modern, general approach for determining a model's Applicability Domain by measuring the density of training data in feature space. [30] |

Essential Considerations for Practitioners

When applying these concepts, scientists should be aware of several critical insights from recent research:

- Prediction errors can be more accurate than training data: Under conditions of Gaussian random error, a QSAR model's predictions on an error-free test set can be closer to the true value than the error-laden training data. This challenges the common assertion that models cannot be more accurate than their training data, though it is often impossible to validate this in practice due to experimental error in test sets [24].

- The r² value is necessary but not sufficient: Relying solely on the coefficient of determination (r²) for external validation is inadequate. A comprehensive assessment should include multiple statistical parameters (e.g., slopes of regression lines, concordance correlation coefficient) to confirm model validity [2].

- Applicability Domain is fundamental for reliable QSAR: The AD is not just an academic exercise. In real-world applications, such as virtual screening for drug discovery, neglecting the AD is a major contributor to false hits. Predictions for compounds outside the AD have a high probability of being inaccurate [28].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling stands as one of the major computational tools employed in medicinal chemistry, used for decades to predict the biological activity of chemical compounds [31]. The validation of these models—ensuring they possess appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity—is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for their reliable application in drug discovery and safety assessment. Poor validation can lead to model failures that misdirect synthetic efforts, waste resources, and potentially allow unsafe compounds to advance in development pipelines. This review examines the tangible consequences of inadequate validation through recent case studies and computational experiments, framing these findings within a broader thesis on QSAR prediction validation research. By comparing different validation approaches and their outcomes, we aim to provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for developing more reliable predictive models.

Case Study 1: Temporal Distribution Shifts in Pharmaceutical Data

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A 2025 investigation by Friesacher et al. systematically evaluated the impact of temporal distribution shifts on uncertainty quantification in QSAR models [32]. The researchers utilized a real-world pharmaceutical dataset containing historical assay results, partitioning the data by time to simulate realistic model deployment scenarios where future compounds may differ systematically from training data. They implemented multiple machine learning algorithms alongside various uncertainty quantification methods, including ensemble-based and Bayesian approaches. Model performance was assessed by measuring the degradation of predictive accuracy and calibration over temporal intervals, with a particular focus on how well different uncertainty estimates correlated with actual prediction errors under distribution shift conditions.

Key Findings and Consequences of Poor Temporal Validation

The study revealed significant temporal shifts in both label and descriptor space that substantially impaired the performance of popular uncertainty estimation methods [32]. The magnitude of distribution shift correlated strongly with the nature of the biological assay, with certain assay types exhibiting more pronounced temporal dynamics. When models were validated using traditional random split validation rather than time-split validation, they displayed overoptimistic performance estimates that failed to predict their degradation in real-world deployment. This validation flaw led to unreliable uncertainty estimates, meaning researchers could not distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy predictions for novel compound classes emerging over time. The practical consequence was misallocated resources toward synthesizing and testing compounds with falsely high predicted activity.

Table 1: Impact of Temporal Distribution Shift on QSAR Model Performance

| Validation Method | Uncertainty Quantification Performance | Real-World Predictive Accuracy | Resource Allocation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Split Validation | Overconfident, poorly calibrated | Significantly overestimated | Low (high false positive rate) |

| Time-Split Validation | Better calibrated to shifts | More realistic estimation | Moderate (improved prioritization) |

| Ongoing Temporal Monitoring | Best calibration to model decay | Most accurate for deployment | High (optimal compound selection) |

Research Reagent Solutions for Temporal Validation

Table 2: Essential Tools for Robust Temporal Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Time-series partitioned datasets | Enables realistic validation by maintaining temporal relationships between training and test compounds |

| Multiple uncertainty quantification methods (ensembles, Bayesian approaches) | Provides robust estimation of prediction reliability under distribution shift |

| Temporal performance monitoring frameworks | Tracks model decay and signals need for model retraining |

| Assay-specific shift analysis tools | Identifies which assay types are most susceptible to temporal effects |

Case Study 2: The Misleading Impact of Experimental Noise on Model Evaluation

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A 2021 study in the Journal of Cheminformatics addressed a fundamental assumption in QSAR modeling: that models cannot produce predictions more accurate than their training data [24]. Researchers used eight datasets with six different common QSAR endpoints, selected because different endpoints should have different amounts of experimental error associated with varying complexity of measurements. The experimental design involved adding up to 15 levels of simulated Gaussian distributed random error to the datasets, then building models using five different algorithms. Critically, models were evaluated on both error-laden test sets (simulating standard practice) and error-free test sets (providing a ground truth comparison). This methodology allowed direct comparison between RMSEobserved (calculated against noisy experimental values) and RMSEtrue (calculated against true values).

Key Findings and Consequences of Ignoring Experimental Error

The results demonstrated that QSAR models can indeed make predictions more accurate than their noisy training data—contradicting a common assertion in the literature [24]. For each level of added error, the RMSE for evaluation on error-free test sets was consistently better than evaluation on error-laden test sets. This finding has profound implications for model validation: the standard practice of evaluating models against assumed "ground truth" experimental values systematically underestimates model performance when those experimental values contain error. In practical terms, this flawed validation approach can lead to the premature rejection of actually useful models, particularly in fields like toxicology where experimental error is often substantial. Conversely, the same validation flaw might cause researchers to overestimate model performance when test set compounds have fortuitously small experimental errors.

Table 3: Impact of Experimental Noise on QSAR Model Evaluation

| Error Condition | Training Data Quality | Test Set Evaluation | Apparent Model Performance | True Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low experimental noise | High | Standard (noisy test set) | Accurate estimate | Good |

| High experimental noise | Low | Standard (noisy test set) | Significant underestimation | Moderate to good |

| Low experimental noise | High | Error-free reference | Accurate estimate | Good |

| High experimental noise | Low | Error-free reference | Accurate estimate | Moderate |

Research Reagent Solutions for Noise-Aware Validation

Table 4: Essential Materials for Properly Accounting Experimental Error

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Datasets with replicate measurements | Enables estimation of experimental error for different endpoints |

| Error simulation frameworks | Allows systematic study of noise impact on model performance |

| Bayesian machine learning methods | Naturally incorporates uncertainty in both training and predictions |

| Parametric bootstrapping tools | Workaround for limited replicates in concentration-response data |

Case Study 3: Misapplied Performance Metrics in Virtual Screening

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A 2025 study challenged traditional QSAR validation paradigms by examining the consequences of using balanced accuracy versus positive predictive value (PPV) for models intended for virtual screening [3]. Researchers developed QSAR models for five expansive datasets with different ratios of active and inactive molecules, creating both balanced models (using down-sampling) and imbalanced models (using original data distribution). The key innovation was evaluating model performance not just by global metrics, but specifically by examining hit rates in the top scoring compounds organized in batches corresponding to well plate sizes (e.g., 128 molecules) used in experimental high-throughput screening. This methodology reflected the real-world constraint where only a small fraction of virtually screened molecules can be tested experimentally.

Key Findings and Consequences of Metric Misapplication

The study demonstrated that training on imbalanced datasets produced models with at least 30% higher hit rates in the top predictions compared to models trained on balanced datasets [3]. While balanced models showed superior balanced accuracy—the traditional validation metric—they performed worse at the actual practical task of virtual screening where only a limited number of compounds can be tested. This misalignment between validation metric and practical objective represents a significant validation failure with direct economic consequences. In one practical application, the PPV-driven strategy for model building resulted in the successful discovery of novel binders of human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) protein, demonstrating the tangible benefits of proper metric selection aligned with the model's intended use.

Table 5: Performance Comparison of Balanced vs. Imbalanced QSAR Models

| Model Characteristic | Balanced Dataset Model | Imbalanced Dataset Model |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced Accuracy | Higher | Lower |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Lower | Higher |

| Hit Rate in Top 128 Predictions | Lower (≥30% less) | Higher |

| Suitability for Virtual Screening | Poor | Excellent |

| Alignment with Experimental Constraints | Misaligned | Well-aligned |

Research Reagent Solutions for Application-Appropriate Validation

Table 6: Essential Tools for Metric Selection and Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| PPV calculation for top-N predictions | Directly measures expected performance for plate-based screening |

| BEDROC metric implementation | Provides emphasis on early enrichment (with parameter tuning) |

| Custom batch-based evaluation frameworks | Aligns validation with experimental throughput constraints |

| Ultra-large chemical libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL) | Enables realistic virtual screening validation at relevant scale |

Comparative Analysis: Cross-Cutting Validation Failures and Solutions

Across these case studies, consistent themes emerge regarding QSAR validation failures and their consequences. The most significant pattern is the disconnect between academic validation practices and real-world application contexts. Temporal shift studies reveal that standard random split validation creates overoptimistic performance estimates [32]. Noise investigations demonstrate that ignoring experimental error in test sets leads to systematic underestimation of true model capability [24]. Virtual screening research shows that optimizing for balanced accuracy rather than task-specific metrics reduces practical utility [3].

These validation failures share common consequences: misallocated research resources, missed opportunities to identify active compounds, and ultimately reduced trust in computational methods. The solutions likewise share common principles: validation strategies must reflect real-world data dynamics, account for measurement imperfections, and align with ultimate application constraints.

The case studies examined in this review demonstrate that poor validation of QSAR models has tangible, negative consequences in drug discovery settings. Traditional validation approaches—while methodologically sound in a narrow statistical sense—often fail to predict real-world performance because they neglect crucial contextual factors: temporal distribution shifts, experimental noise, and misalignment between validation metrics and application goals. The good news is that researchers now have both the methodological frameworks and empirical evidence needed to implement more sophisticated validation practices. By adopting time-aware validation splits, accounting for experimental error in performance assessment, and selecting metrics aligned with practical objectives, the field can develop QSAR models that deliver more reliable predictions and ultimately accelerate drug discovery. Future validation research should continue to bridge the gap between statistical idealizations and the complex realities of pharmaceutical research and development.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models represent a critical computational approach in regulatory science, predicting the activity or properties of chemical substances based on their molecular structure [33]. These computational tools have evolved from research applications to essential components of regulatory compliance across chemical and pharmaceutical sectors. The validation of these models ensures they produce reliable, reproducible results that can support regulatory decision-making, potentially reducing animal testing and accelerating product development [34].

The global regulatory landscape has progressively incorporated QSAR methodologies through structured frameworks that establish standardized validation principles. This guide examines three pivotal frameworks governing QSAR validation: the OECD Principles, which provide the foundational scientific standards; REACH, which implements these principles within European chemical regulation; and ICH M7, which adapts them for pharmaceutical impurity assessment [34] [35]. Understanding the comparative requirements, applications, and technical specifications of these frameworks is essential for researchers, regulatory affairs professionals, and chemical safety assessors navigating compliance requirements in their respective fields.

Foundational OECD Validation Principles

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) established the fundamental principles for QSAR validation during a series of expert meetings culminating in 2004 [34]. These principles originated from the need to harmonize regulatory acceptance of QSAR models across member countries, particularly as legislation like REACH created massive data requirements that traditional testing couldn't feasibly meet. The OECD principles provide the scientific foundation upon which specific regulatory frameworks build their QSAR requirements.

The Five Validation Principles

Principle 1: Defined Endpoint: The endpoint measured by the QSAR model must be transparently and unambiguously defined. This addresses the complication that "models can be constructed using data measured under different conditions and various experimental protocols" [34]. Without clear endpoint definition, regulatory acceptance is compromised by uncertainty about what the model actually predicts.

Principle 2: Unambiguous Algorithm: The algorithm used for model construction must be explicitly defined. As noted in the OECD documentation, commercial models often face challenges here since "organizations selling the model do not provide the information and it is not open to public" for proprietary reasons [34]. This principle emphasizes transparency in the mathematical foundation of predictions.

Principle 3: Defined Applicability Domain: The model's scope and limitations must be clearly specified regarding chemical structural space, physicochemical properties, and mechanisms of action. "Each QSAR model is directly joint with chemical structure of a molecule," and its valid application depends on operating within established boundaries [34].

Principle 4: Appropriate Statistical Measures: Models must demonstrate performance through suitable internal and external validation statistics. The OECD emphasizes that "external validation with independent series of data should be used," though cross-validation may substitute when external datasets are unavailable [34]. Standard metrics include Q² (cross-validated correlation coefficient), with values >0.5 considered "good" and >0.9 "excellent" [34].

Principle 5: Mechanistic Interpretation: Whenever possible, the model should reflect a biologically meaningful mechanism. This principle "should push authors of the model to consider an interpretation of molecular descriptors used in construction of the model in mechanism of the effect" [34]. Mechanistic plausibility strengthens regulatory confidence beyond purely statistical performance.

REACH Regulation and QSAR Implementation

The REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) regulation, enacted in 2007, represents the European Union's comprehensive framework for chemical safety assessment [34]. REACH fundamentally shifted the burden of proof to industry, requiring manufacturers and importers to generate safety data for substances produced in quantities exceeding one tonne per year. This created an enormous demand for toxicity and ecotoxicity data that traditional testing methods could not practically fulfill, making QSAR approaches essential to the regulation's implementation.

REACH Requirements and QSAR Integration

Under REACH, registrants must submit technical dossiers containing information on substance properties, uses, classification, and safe use guidance [34]. For higher production volume chemicals (≥10 tonnes/year), a Chemical Safety Report is additionally required. The regulation explicitly recognizes QSAR and other alternative methods as valid approaches for generating required data, particularly to "reduce or eliminate" vertebrate animal testing [34]. This regulatory acceptance comes with the strict condition that QSAR models must comply with the OECD validation principles.

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) in Helsinki manages the REACH implementation and has developed specific tools to facilitate QSAR application. The QSAR Toolbox, developed collaboratively by OECD, ECHA, and the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC), provides a freely available software platform that supports chemical category formation and read-across approaches [34]. This tool specifically addresses the "categorization of chemicals" – grouping substances with "similar physicochemical, toxicological and ecotoxicological properties" – to enable extrapolation of experimental data across structurally similar compounds [34].

Practical Implementation and Challenges

ECHA continues to refine its approach to QSAR assessment, recently developing the (Q)SAR Assessment Framework based on OECD principles to "evaluate model predictions and ensure regulatory consistency" [36]. This framework offers "standardized reporting templates for model developers and users, and includes checklists to support regulatory decision-making" [36]. The agency provides ongoing training to stakeholders, including webinars focused on applying the assessment framework to environmental and human health endpoints [36].

Despite these supportive measures, practical challenges remain in REACH implementation. The historical context of "divergent interpretations among regulatory agencies" created inefficiencies that unified frameworks aim to resolve [37]. Additionally, the requirement for defined applicability domains (OECD Principle 3) presents technical hurdles for novel chemical space where experimental data is sparse. Nevertheless, REACH represents the most extensive regulatory integration of QSAR methodologies globally, serving as a model for other jurisdictions.

ICH M7 Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Impurities

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M7 guideline provides a specialized framework for assessing mutagenic impurities in pharmaceuticals, representing a targeted application of QSAR principles within drug development and manufacturing [35]. First adopted in 2014 and updated through ICH M7(R1) and M7(R2), this guideline establishes procedures for "identification, categorization, and control of mutagenic impurities to limit potential carcinogenic risk" [35]. Unlike the broader REACH regulation, ICH M7 focuses specifically on DNA-reactive impurities that may present carcinogenic risks even at low exposure levels.

Computational Assessment Requirements

ICH M7 mandates a structured approach to impurity assessment that systematically integrates computational methodologies. The guideline requires that each potential impurity undergoes evaluation through two complementary (Q)SAR prediction methodologies – one using expert rule-based systems and one using statistical-based methods [35]. This dual-model approach balances the strengths of different methodologies: rule-based systems flag known structural alerts, while statistical models identify broader patterns potentially missed by rule-based systems.

The predictions from these models determine impurity classification into one of five categories:

Table 1: ICH M7 Impurity Classification and Control Strategies

| Class | Definition | Control Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Known mutagenic carcinogens | Controlled at compound-specific limits, often requiring highly sensitive analytical methods |

| Class 2 | Known mutagens with unknown carcinogenic potential | Controlled at or below Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC) of 1.5 μg/day |

| Class 3 | Alerting structures, no mutagenicity data | Controlled as Class 2, or additional testing (e.g., Ames test) to refine classification |

| Class 4 | Alerting structures with sufficient negative data | No special controls beyond standard impurity requirements |

| Class 5 | No structural alerts | No special controls beyond standard impurity requirements |

Source: Adapted from ICH M7 Guideline [35]

When computational predictions conflict or prove equivocal, the guideline mandates expert review to reach a consensus determination [35]. This integrated approach allows manufacturers to screen hundreds of potential impurities without synthesis, focusing experimental resources on higher-risk compounds.

Analytical and Control Requirements

For impurities classified as mutagenic (Classes 1-3), ICH M7 establishes strict control thresholds based on the Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC) concept. The default TTC for lifetime exposure is 1.5 μg/day, representing a theoretical cancer risk of <1:100,000 [35]. The guideline recognizes higher thresholds for shorter-term exposures, with 120 μg/day permitted for treatments under one month [35]. The recent M7(R2) update introduced Compound-Specific Acceptable Intakes (CSAI), allowing manufacturers to propose higher limits when supported by sufficient genotoxicity and carcinogenicity data [35].

Analytically, controlling impurities at these levels presents significant technical challenges, often requiring highly sensitive methods like LC-MS/MS. The guideline emphasizes Quality Risk Management throughout development and manufacturing to ensure impurities remain below established limits [35]. This includes evaluating synthetic pathways to identify potential impurity formation and establishing purification processes that effectively remove mutagenic impurities.

Comparative Analysis of Frameworks

Regulatory Scope and Focus

While all three frameworks incorporate QSAR methodologies, they differ fundamentally in scope and application. The OECD Principles provide the scientific foundation without direct regulatory force, serving as guidance for member countries developing chemical regulations [34]. REACH implements these principles within a comprehensive chemical management system covering all substances manufactured or imported in the EU above threshold quantities [34]. In contrast, ICH M7 applies specifically to pharmaceutical impurities, creating a specialized framework for a narrow but critical safety endpoint [35].

Table 2: Framework Comparison - Scope, Endpoints, and Methods

| Framework | Regulatory Scope | Primary Endpoints | QSAR Methodology | Key Tools/Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OECD Principles | Scientific guidance for member countries | All toxicological and ecotoxicological endpoints | Flexible, based on five validation principles | QSAR Toolbox, various commercial and open-source models |

| REACH | All chemicals ≥1 tonne/year in EU | Comprehensive toxicity, ecotoxicity, environmental fate | OECD-compliant models, read-across, categorization | QSAR Toolbox, AMBIT, ECHA (Q)SAR Assessment Framework |

| ICH M7 | Pharmaceutical impurities | Mutagenicity (Ames test endpoint) | Two complementary models (rule-based + statistical) | Derek Nexus, Sarah Nexus, Toxtree, Leadscope |

The frameworks also differ in their specific technical requirements. REACH employs a flexible approach where QSAR represents one of several acceptable data sources, including read-across from similar compounds and in vitro testing [34]. ICH M7 mandates more specific methodology, requiring two complementary QSAR approaches with resolution mechanisms for conflicting predictions [35]. This reflects the different risk contexts: REACH addresses broader chemical safety, while ICH M7 focuses on a specific high-concern endpoint for human medicines.

Validation and Acceptance Criteria

All three frameworks require adherence to the core OECD validation principles, but operationalize them differently. Under REACH, the QSAR Assessment Framework developed by ECHA provides "standardized reporting templates for model developers and users, and includes checklists to support regulatory decision-making" [36]. This framework helps implement the OECD principles consistently across the vast number of substances subject to REACH requirements.

ICH M7 maintains particularly rigorous standards for model performance, requiring documented sensitivity and specificity relative to experimental mutagenicity data [35]. For example, one cited evaluation found that "rule-based TOXTREE achieved 80.7% sensitivity (accuracy 72.2%) in Ames mutagenicity prediction" [35]. The pharmaceutical context demands higher certainty for this specific endpoint due to direct human exposure implications.

The emerging trend across all frameworks is toward greater standardization and harmonization. The recent consolidation of ICH stability guidelines (Q1A through Q1E) into a single document reflects this direction, addressing "divergent interpretations among regulatory agencies" through unified guidance [37]. Similarly, ECHA's work on the (Q)SAR Assessment Framework aims to promote "regulatory consistency" in computational assessment [36].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized QSAR Validation Workflow

The regulatory acceptance of QSAR predictions depends on rigorous validation protocols that demonstrate model reliability and applicability. The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for regulatory QSAR validation, incorporating requirements from OECD, REACH, and ICH frameworks:

This systematic approach ensures models meet regulatory standards before application to substance assessment. The process emphasizes transparency at each stage, with particular focus on defining the applicability domain (Principle 3) and providing appropriate statistical measures (Principle 4).

ICH M7 Specific Assessment Methodology

For pharmaceutical impurities under ICH M7, a specialized methodology implements the dual QSAR prediction requirement:

Table 3: ICH M7 Computational Assessment Protocol

| Step | Activity | Methodology | Documentation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Impurity Identification | List all potential impurities from synthesis | Analysis of synthetic pathway, degradation chemistry | Structures, rational for inclusion, theoretical yields |

| 2. Rule-Based Assessment | Screen for structural alerts | Expert system (e.g., Derek Nexus, Toxtree) | Full prediction report, reasoning for flags |

| 3. Statistical Assessment | Evaluate using machine learning | Statistical model (e.g., Sarah Nexus, Leadscope) | Prediction probability, confidence measures |

| 4. Consensus Analysis | Resolve conflicting predictions | Expert review, additional data if needed | Rationale for final classification |