A Practical Guide to In Silico Methods for Academic Drug Discovery: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Validation

This guide provides academic researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive roadmap for integrating in silico methods into the drug discovery pipeline.

A Practical Guide to In Silico Methods for Academic Drug Discovery: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This guide provides academic researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive roadmap for integrating in silico methods into the drug discovery pipeline. It covers foundational principles, from overcoming the high costs and extended timelines of traditional drug development to leveraging the growing amount of available biological data. The article explores key methodological applications, including AI-driven target identification, virtual screening, and machine learning for lead optimization. It also addresses critical challenges such as data sparsity and model bias, and provides frameworks for rigorous experimental validation and benchmarking. By synthesizing current trends, real-world case studies, and strategic insights, this guide aims to empower academic teams to accelerate the development of safe and effective therapeutics.

The In Silico Revolution: Foundations for Modern Academic Drug Discovery

Defining In Silico Drug Discovery and Its Core Value Proposition

In silico drug discovery represents a fundamental paradigm shift in pharmaceutical research, defined as the utilization of computational methods to simulate, predict, and design drug candidates before physical experiments are conducted [1]. The term "in silico," derived from silicon in computer chips, signifies research performed via computer simulation rather than traditional wet-lab approaches [1]. This field has evolved from simple mathematical models to sophisticated, data-intensive platforms that now form an integral part of modern drug discovery pipelines [2] [1].

The core value proposition of in silico methods addresses critical challenges in conventional drug development: excessively high costs, prolonged timelines, and unacceptable failure rates. Traditional drug discovery requires an average investment of $1.8–2.8 billion and spans 12–15 years from initial discovery to market approval, with approximately 96% of drug candidates failing during development [2] [3]. In silico technologies fundamentally rewrite this equation by enabling rapid virtual screening of massive compound libraries, predicting biological activity and toxicity computationally, and optimizing lead compounds with unprecedented efficiency—drastically reducing the number of molecules that require synthesis and physical testing [1] [3].

Key Methodologies and Technical Approaches

In silico drug discovery encompasses two primary computational approaches, selected based on available biological knowledge about the drug target.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

SBDD relies on three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, obtained experimentally through X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy, or computationally via prediction methods [2] [3]. Key techniques include:

Molecular Docking: This method predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target receptor. Docking algorithms search through numerous conformations, scoring each pose to identify those with optimal binding affinities [2] [1]. The general workflow encompasses target preparation, binding site identification, ligand preparation, conformational sampling, and scoring function evaluation [2].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD provides atomistic trajectories over time, enabling researchers to observe conformational changes, binding stability, and interaction dynamics between drug candidates and their targets in a physiological context [1]. These simulations help understand not only binding efficiency but also effects on protein function.

Virtual High-Throughput Screening (vHTS): By combining docking algorithms with MD validation, vHTS rapidly assesses extensive compound libraries—in some cases encompassing billions of compounds—to identify promising candidates for further investigation [1].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

When structural information of the target is unavailable, LBDD methodologies provide powerful alternatives:

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling: QSAR establishes mathematical relationships between chemical structures and biological activities using molecular descriptors ranging from 1D (e.g., molecular weight, logP) to 3D (molecular shape, electrostatic properties) [4]. These models predict efficacy and toxicity of novel compounds based on their structural similarity to known active molecules.

Pharmacophore Modeling: This technique defines the essential spatial arrangement of molecular features necessary for biological activity—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings—enabling virtual screening for compounds sharing these critical characteristics [1].

Machine Learning Applications: Advanced algorithms learn from large chemical and biological datasets to predict drug-target interactions, adverse effects, and pharmacokinetic profiles with increasing accuracy [1] [3]. Deep learning tools now routinely refine docking scores, generate novel molecular structures, and optimize lead compounds.

Table 1: Core Methodologies in In Silico Drug Discovery

| Methodology | Data Requirements | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Protein 3D structure | Binding pose prediction, Virtual screening | Atomic-level interaction insights |

| MD Simulations | Protein-ligand complex | Binding stability, Conformational dynamics | Time-resolved biological context |

| QSAR Modeling | Compound libraries with activity data | Activity prediction, Toxicity assessment | No protein structure required |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Known active compounds | Virtual screening, Lead optimization | Identifies essential interaction features |

| Machine Learning | Large chemical/biological datasets | Property prediction, De novo design | Recognizes complex nonlinear patterns |

Experimental Workflow Integration

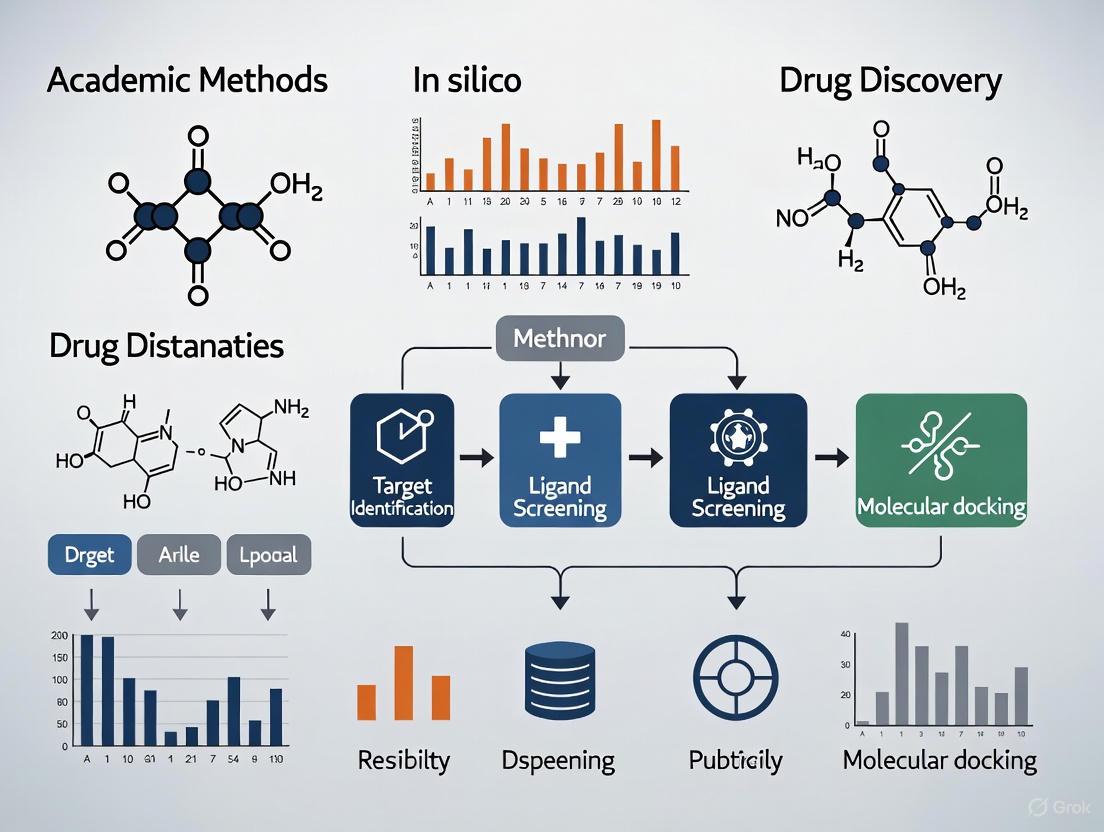

The power of in silico methods is maximized when integrated into coherent workflows. The diagram below illustrates a typical integrated drug discovery pipeline:

In Silico Drug Discovery Workflow

This integrated approach demonstrates how computational methods guide experimental efforts, with each stage providing increasingly rigorous filtration to identify viable drug candidates.

Successful implementation of in silico drug discovery requires access to specialized computational tools, databases, and software platforms that constitute the modern researcher's toolkit.

Key Databases and Knowledge Bases

Protein Data Bank (PDB): The primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complex assemblies, essential for structure-based approaches [2].

UniProtKB/TrEMBL: Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information database containing over 231 million sequence entries as of 2022, used for target identification and homology modeling [2].

PubChem & ChEMBL: Extensive databases of chemical molecules and their biological activities, containing screening data against thousands of protein targets, enabling ligand-based design and virtual screening [3].

ZINC Database: Curated collection of commercially available compounds specifically tailored for virtual screening, typically containing over 100 million purchasable compounds in ready-to-dock formats [5].

Software and Algorithmic Platforms

Homology Modeling Tools: Software such as MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, and Phyre2 predict protein 3D structures using comparative modeling techniques when experimental structures are unavailable [2].

Molecular Docking Suites: Platforms like AutoDock, Glide (Schrödinger), and GOLD provide algorithms for predicting ligand binding poses and scoring binding affinities [1] [6].

Molecular Dynamics Engines: Software including GROMACS, AMBER, and Desmond (Schrödinger) simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing insights into dynamic binding processes [1] [5].

QSAR Modeling Environments: Tools like RDKit and Scikit-Learn provide open-source platforms for developing machine learning models that correlate chemical structure with biological activity [4].

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for In Silico Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function | Access Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling | SWISS-MODEL, MODELLER | Protein structure prediction | Academic free, Commercial |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock, Glide, GOLD | Ligand pose prediction, Virtual screening | Open source, Commercial |

| MD Simulations | GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond | Biomolecular dynamics analysis | Open source, Commercial |

| QSAR/Machine Learning | RDKit, Scikit-Learn | Predictive model development | Open source |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, pkCSM | Pharmacokinetic property prediction | Web server, Open access |

Quantitative Impact: Efficiency Gains and Cost Reduction

The implementation of in silico methods delivers measurable improvements across key drug discovery metrics, fundamentally enhancing research productivity and resource allocation.

Timeline Acceleration

Traditional early-stage drug discovery typically requires 2.5 to 4 years from project initiation to preclinical candidate nomination [7]. Companies leveraging integrated AI-driven in silico platforms have demonstrated radical compression of these timelines. For instance, Insilico Medicine reported nominating 20 preclinical candidates between 2021-2024 with an average turnaround of just 12-18 months per program—representing a 40-60% reduction in timeline [7]. In specific cases, the time to first clinical trials has been reduced from six years to as little as two and a half years using AI-driven in silico platforms [1].

Resource Optimization

In silico methods dramatically reduce the number of compounds requiring physical synthesis and testing. Traditional high-throughput screening might involve testing hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds physically, whereas virtual screening can evaluate billions of compounds computationally [1]. Insilico Medicine's programs required only 60-200 molecules synthesized and tested per program—orders of magnitude lower than conventional approaches [7]. This optimization translates directly into significant cost savings in chemical synthesis, compound management, and assay implementation.

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of In Silico Methods on Drug Discovery Efficiency

| Performance Metric | Traditional Approach | In Silico Approach | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline to Preclinical Candidate | 2.5-4 years | 1-1.5 years | 40-60% reduction |

| Compounds Synthesized per Program | Thousands to hundreds of thousands | 60-200 molecules | >90% reduction |

| Probability of Clinical Success | 13.8% (all development phases) | Significant early risk mitigation | Substantial improvement |

| Cost per Candidate Identified | Millions of USD | Significant reduction | >50% estimated savings |

Case Studies and Clinical Validation

The credibility of in silico drug discovery is demonstrated through multiple successfully developed therapeutics that have gained regulatory approval.

HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors

Several HIV-1 protease inhibitors, including saquinavir, indinavir, and ritonavir, were developed using structure-based in silico design approaches [3]. These drugs were designed to fit precisely into the viral protease active site, computationally optimizing binding interactions before synthesis, demonstrating the power of molecular docking and structure-based design for addressing critical medical needs [3].

TNIK Inhibitor for Fibrotic Diseases

Insilico Medicine developed Rentosertib (ISM001-055), the world's first TNIK inhibitor discovered and designed with generative AI, from target identification to preclinical candidate nomination [7]. The compound has progressed through clinical trials, with phase IIa data published in 2025 demonstrating safety and efficacy—representing the first clinical proof-of-concept for an AI-driven drug development pipeline [7].

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Drug Discovery

In silico methods have identified natural compounds like hesperidin, quercetin, and kaempferol that show strong binding energies for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), providing new starting points for HBV therapeutic development [5]. These approaches have revealed previously overlooked viral targets and facilitated the creation of specific inhibitors through molecular docking and dynamics simulations [5].

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The field of in silico drug discovery continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transitioning from promising technologies to foundational capabilities, with generative AI now creating novel molecular structures with optimized properties [1] [6]. The recent regulatory shift toward accepting in silico evidence, including the FDA's 2025 announcement phasing out mandatory animal testing for many drug types, signals growing confidence in computational methodologies [8]. The emergence of digital twins—comprehensive computer models of biological systems—offers potential for simulating clinical trials and personalized therapeutic responses [8].

Despite remarkable progress, methodological challenges remain. Accuracy of predictive models still suffers from approximations in scoring functions and force fields [1]. Modeling complex biological systems in their physiological context presents substantial computational demands [1]. Reproducibility and standardization across algorithms and software implementations require continued community effort [1].

In conclusion, in silico drug discovery has matured from a supplementary approach to a central paradigm in pharmaceutical research. Its core value proposition—dramatically accelerated timelines, significantly reduced costs, and improved decision-making through computational prediction—positions it as an indispensable component of modern drug development. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the integration of in silico methods with experimental validation will further solidify their role in delivering novel therapeutics to address unmet medical needs. For academic researchers and drug development professionals, proficiency in these computational approaches has transitioned from advantageous to essential for cutting-edge research productivity.

The biopharmaceutical industry is navigating an unprecedented productivity crisis. Despite record levels of research and development (R&D) investment and over 23,000 drug candidates in development, success rates are declining precipitously [9]. The phase transition success rate for Phase 1 drugs has plummeted to just 6.7% in 2024, compared to 10% a decade ago, while the internal rate of return for R&D investment has fallen to 4.1%—well below the cost of capital [9]. This whitepaper examines the core drivers of this crisis and outlines how in silico methods—computational approaches leveraging artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and sophisticated modeling—are transforming early-stage academic drug discovery research to address these challenges.

The Scale of the Crisis: Quantifying the Problem

The drug discovery and development process is characterized by extensive timelines, astronomical costs, and staggering attrition rates that have worsened despite technological advances.

The Timeline and Attrition Funnel

The journey from concept to approved therapy typically spans 10 to 15 years, with the clinical phase alone averaging nearly 8 years [10]. This protracted timeline exists within a high-risk environment where only approximately 1 in 250 compounds entering preclinical testing will ultimately reach patients [10]. The likelihood of approval (LOA) for a drug candidate entering Phase I clinical trials stands at a mere 7.9% [11].

Table 1: Drug Development Lifecycle by the Numbers

| Development Stage | Average Duration | Probability of Transition to Next Stage | Primary Reason for Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Preclinical | 2-4 years | ~0.01% (to approval) | Toxicity, lack of effectiveness |

| Phase I | 2.3 years | ~52% | Unmanageable toxicity/safety |

| Phase II | 3.6 years | ~29% | Lack of clinical efficacy |

| Phase III | 3.3 years | ~58% | Insufficient efficacy, safety |

| FDA Review | 1.3 years | ~91% | Safety/efficacy concerns [11] |

The Financial Burden

The financial model of drug development is built upon the reality of attrition, where profits from the few successful drugs must cover the sunk costs of numerous failures [11]. While out-of-pocket expenses are substantial, the true cost is the capitalized cost, which accounts for the time value of money invested over more than a decade with no guarantee of return [11].

- Direct Costs: Clinical trials account for approximately 68-69% of total out-of-pocket R&D expenditures [11].

- Capitalized Costs: Estimates place the average capitalized cost at $2.6 billion per approved drug when accounting for failures and capital costs [11].

- Impact of Delay: A one-year delay in a late-stage clinical trial has a disproportionately large effect on the final capitalized cost due to the significant investment already deployed [11].

The Productivity Paradox

Despite increased R&D investment exceeding $300 billion annually, productivity metrics are moving in the wrong direction [9]. R&D margins are expected to decline significantly from 29% of total revenue down to 21% by the end of the decade [9]. This decline is driven by three interconnected factors:

- The commercial performance of the average new drug launch is shrinking

- Rising costs per new drug approval due to more complex trials and decreasing success rates

- Growing pipeline attrition rates [9]

In Silico Methods: A Paradigm Shift for Academic Research

In silico methods—computational approaches for drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction—represent a transformative opportunity to address these challenges by mitigating the high costs, low success rates, and extensive timelines of traditional development [12]. These approaches efficiently leverage the growing amount of available biological and chemical data to make more informed decisions earlier in the discovery process.

Ligand-Based Drug Design

Ligand-based drug design (LBDD) is a knowledge-based approach that extracts essential chemical features from known active compounds to predict properties of new molecules [13]. This method is particularly valuable when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown.

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Similarity Search

The similarity-based drug design process follows a systematic workflow:

- Query Compound Identification: Select a target molecule with known biological properties as the query for chemical search

- Database Screening: Search chemical databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem, DrugBank, BindingDB) using molecular fingerprints

- Similarity Calculation: Quantify chemical similarity using the Tanimoto index, typically with a threshold of 0.7-0.8 for significant similarity

- Hit Identification: Identify structurally similar ligands with potentially improved bioactivities

- Compound Modification: Suggest new molecules through scaffold hopping and functional group optimization [13]

Target Prediction Using Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA)

Ligand-based target prediction infers molecular targets by comparing query compounds to target-annotated ligands in databases. The Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) addresses the "bioactivity cliffs" problem by:

- Calculating chemical similarity scores between the query compound and all target sets in the database

- Comparing these scores against a random background distribution using statistical methods similar to BLAST

- Generating a P-value representing the significance of the association between the query compound and each potential target

- Identifying the most probable targets based on statistically significant associations [13]

Structure-Based Drug Design

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) utilizes the three-dimensional structure of biological targets to identify shape-complementary ligands with optimal interactions [13]. This approach has been revolutionized by advances in structural biology and computational power.

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Docking

Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target (receptor). The standard protocol involves:

Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure from sources like Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate with AlphaFold

- Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges

- Define binding site coordinates

Ligand Preparation:

- Generate 3D conformations from chemical structure

- Assign appropriate bond orders and formal charges

- Energy minimize the structure using molecular mechanics

Docking Simulation:

- Sample possible ligand conformations and orientations within the binding site

- Score each pose using scoring functions (e.g., force field-based, empirical, knowledge-based)

- Select top-ranked poses for further analysis

Post-Docking Analysis:

Panel Docking for Target Prediction

Structure-based target prediction identifies molecular targets through systematic docking of a compound against multiple potential targets:

- Target Selection: Curate a diverse panel of structurally characterized potential drug targets

- Parallel Docking: Perform docking simulations against all targets in the panel using standardized parameters

- Consensus Scoring: Rank targets based on docking scores and interaction profiles

- Target Prioritization: Identify the most probable targets based on complementary binding interactions [13]

Figure 1: Molecular Docking Workflow

Network Poly-Pharmacology

Network pharmacology represents a paradigm shift from the traditional "one drug, one target" hypothesis to a more comprehensive "multiple drugs, multiple targets" approach [13]. This framework acknowledges that most drugs interact with multiple biological targets, which can explain both therapeutic effects and side effects.

Experimental Protocol: Drug-Target Network Analysis

Data Collection:

- Compile drug-target interaction data from public databases (ChEMBL, BindingDB, IUPHAR)

- Gather chemical structures and target protein information

- Collect known side effect and indication data

Network Construction:

- Create a bipartite network with drugs and targets as two node types

- Establish edges based on confirmed or predicted interactions

- Weight edges based on binding affinity or interaction strength

Network Analysis:

- Identify network communities and clusters

- Calculate centrality measures to identify key targets and privileged scaffolds

- Detect network motifs associated with specific therapeutic or adverse effects

Predictive Modeling:

- Apply machine learning algorithms to predict novel drug-target interactions

- Use canonical component analysis (CCA) to correlate binding profiles with side effects

- Generate hypotheses for drug repurposing and combination therapies [13]

Research Reagent Solutions: The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of in silico drug discovery requires access to comprehensive data resources and computational tools. The table below details essential resources for academic researchers.

Table 2: Key Research Resources for In Silico Drug Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Database | Target-annotated bioactive molecules with binding, functional and ADMET data | Public |

| PubChem | Database | Chemical structures, biological activities, and safety information for small molecules | Public |

| DrugBank | Database | Comprehensive drug and drug target information with detailed mechanism data | Public |

| AlphaFold | Tool | Protein structure prediction with high accuracy for targets without crystal structures | Public |

| AutoDock | Software | Molecular docking simulation for protein-ligand interaction prediction | Open Source |

| SwissADME | Web Tool | Prediction of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties | Public |

| CETSA | Experimental Method | Validation of direct target engagement in intact cells and tissues | Commercial |

| FAIRsharing | Portal | Curated resource on data standards, databases, and policies in life sciences | Public |

Integrated Workflows: Combining In Silico and Experimental Approaches

The most effective modern drug discovery pipelines integrate multiple computational and experimental approaches to leverage their complementary strengths.

AI-Driven Hit-to-Lead Optimization

The traditionally lengthy hit-to-lead (H2L) phase is being rapidly compressed through integrated AI-guided workflows. A 2025 study demonstrated this approach by using deep graph networks to generate over 26,000 virtual analogs, resulting in sub-nanomolar MAGL inhibitors with more than 4,500-fold potency improvement over initial hits [6]. This represents a model for data-driven optimization of pharmacological profiles that can reduce discovery timelines from months to weeks.

Experimental Validation of Computational Predictions

Computational predictions require experimental validation to establish translational relevance. Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as a leading approach for validating direct target engagement in intact cells and tissues [6]. Recent work applied CETSA in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry to quantify drug-target engagement of DPP9 in rat tissue, confirming dose- and temperature-dependent stabilization ex vivo and in vivo [6]. This integration of computational prediction with empirical validation represents the gold standard for modern drug discovery.

Figure 2: Integrated In Silico-Experimental Workflow

Future Directions and Implementation Recommendations

Emerging Technologies and Regulatory Evolution

The field of in silico drug discovery is rapidly evolving, with several key developments shaping its future:

- Regulatory Acceptance: The FDA has announced plans to phase out mandatory animal testing for many drug types, signaling a paradigm shift toward in silico methodologies [8]. This regulatory evolution is creating new opportunities for computational approaches to contribute to safety and efficacy assessment.

- AI and Machine Learning: Advanced ML models are transitioning from predicting simple binding events to complex pharmacological properties, including toxicity, bioavailability, and clinical outcomes [6]. The integration of pharmacophoric features with protein-ligand interaction data has demonstrated up to 50-fold improvement in hit enrichment rates compared to traditional methods [6].

- Data Standardization: The lack of sufficiently implemented data standards remains a significant challenge [14]. Widespread adoption of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles is essential for maximizing the value of drug discovery data and enabling robust AI/ML applications [14].

Strategic Implementation for Academic Research Centers

For academic research institutions aiming to leverage in silico methods, several strategic considerations are critical:

- Infrastructure Investment: Establish high-performance computing resources and cloud computing access for computationally intensive simulations

- Cross-Disciplinary Training: Develop training programs that integrate computational and experimental approaches across biology, chemistry, and data science

- Data Management: Implement standardized data management practices following FAIR principles to ensure data quality and reusability

- Industry Collaboration: Foster partnerships with pharmaceutical companies and technology developers to access specialized tools and real-world validation datasets

- Regulatory Engagement: Proactively engage with regulatory agencies to understand evolving requirements for computational evidence in drug development submissions

The drug discovery crisis, characterized by unsustainable costs, extended timelines, and high attrition rates, demands transformative solutions. In silico methods represent a paradigm shift that enables academic researchers to make more informed decisions earlier in the discovery process, potentially derisking the development pipeline and increasing the probability of clinical success. By integrating ligand-based and structure-based approaches with experimental validation within a network pharmacology framework, researchers can simultaneously optimize for efficacy and safety while compressing discovery timelines. As these computational approaches continue to evolve and gain regulatory acceptance, they will become increasingly central to successful drug discovery, potentially restoring productivity to the biopharmaceutical R&D enterprise.

The field of academic drug discovery is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by two powerful, interconnected forces: the unprecedented growth of large-scale biological data and rapid advancements in computational power. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with biological research has given rise to sophisticated in silico methods that are reshaping traditional research and development (R&D) pipelines [15] [16]. These technologies enable researchers to simulate biological systems, predict drug-target interactions, and optimize lead compounds with remarkable speed and accuracy, significantly reducing the reliance on costly and time-consuming wet-lab experiments [15] [17]. This whitepaper details the core drivers behind this shift, provides quantitative insights into the computational landscape, outlines foundational experimental protocols, and visualizes the key workflows empowering the modern academic drug discovery scientist.

The Dual Engines of Change: Data and Compute

The Biological Data Deluge

The collapse of sequencing costs and the proliferation of high-throughput technologies have led to an explosion in the volume, variety, and velocity of biological data. This data forms the essential substrate for training and validating the computational models used in modern drug discovery.

Table: Key Sources and Types of Large-Scale Biological Data

| Data Type | Description | Primary Sources | Applications in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence data | NGS (e.g., Illumina, Oxford Nanopore), Whole Genome Sequencing [18] | Target identification, disease risk prediction via polygenic risk scores, pharmacogenomics [18] [16]. |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance, structure, and interaction data | Mass Spectrometry, AlphaFold DB [19] [20] | Target validation, understanding mechanism of action, predicting protein-ligand interactions [12] [15]. |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression data | Single-cell RNA sequencing, Spatial Transcriptomics [18] [16] | Understanding disease heterogeneity, identifying novel disease subtypes, biomarker discovery. |

| Metabolomics | Profiles of small-molecule metabolites | Mass Spectrometry, NMR [18] | Discovering disease biomarkers, understanding drug metabolism and off-target effects. |

| Multi-omics | Integrated data from multiple layers (genomics, proteomics, etc.) | Combined analysis from public repositories (NCBI, EMBL-EBI, DDBJ) [21] [18] | Comprehensive view of biological systems, linking genetic information to molecular function and phenotype [18]. |

The Computational Power Surge

The analysis of these massive datasets necessitates immense computational resources, driving and being enabled by concurrent advances in hardware and cloud infrastructure. The demand for specialized processors like GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) and TPUs (Tensor Processing Units) has skyrocketed, as they are essential for training complex deep learning models.

Table: Quantitative Landscape of Computational Demand and Infrastructure (2025)

| Metric | Value / System | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Global AI Compute Demand (Projected 2030) | 200 Gigawatts [19] | Power requirement highlights the massive energy consumption of modern AI data centers. |

| Projected AI Infrastructure Spending (by 2029) | \$2.8 Trillion [19] | Reflects massive capital investment by tech giants and enterprises to build compute capacity. |

| Nvidia Data Center (AI) Sales (Q2 2025) | \$41.1 Billion (Quarterly) [19] | A 56% year-over-year increase, indicating intense demand for AI chips across industries, including biotech. |

| Sample Supercomputer | Isambard-AI (UK) [19] | Utilizes 5,448 Nvidia GH200 GPUs, delivering 21 exaflops of AI performance for research in drug discovery and healthcare. |

| In-silico Drug Discovery Market (2025) | \$4.17 Billion [17] | Projected to grow to \$10.73 billion by 2034 (CAGR 11.09%), demonstrating rapid adoption of these methods. |

The shift to cloud computing platforms (e.g., AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure) has democratized access to this computational power, allowing academic researchers to scale resources elastically without major upfront investment in local hardware [21] [18]. Furthermore, emerging paradigms like quantum computing hold the potential to solve currently intractable problems, such as precisely simulating molecular interactions at quantum mechanical levels, which could revolutionize drug design [16].

Foundational Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The convergence of data and compute has enabled several core in silico methodologies that are now standard in the academic drug discovery toolkit.

Protocol: AI-Driven Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction

Objective: To computationally predict the binding affinity and functional interaction between a candidate small molecule (drug) and a protein target (e.g., a kinase, receptor).

Workflow:

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Ligand Preparation: Collect 2D/3D structures of small molecules from databases like PubChem or ZINC. Prepare structures by adding hydrogens, generating plausible tautomers, and conducting energy minimization.

- Target Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or use a computationally predicted structure from AlphaFold DB [19] [12]. Process the structure by removing water molecules, adding hydrogens, and assigning correct protonation states.

- Data Labeling: Compile a dataset of known interacting and non-interacting drug-target pairs from public sources (e.g., BindingDB, ChEMBL). This labeled data is used for supervised learning.

Feature Engineering:

- Ligand Features: Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices) or use learned representations from deep learning models.

- Target Features: Extract features from the protein sequence (e.g., amino acid composition, physicochemical properties) or structure (e.g., surface topology, pocket volume, interaction fingerprints) [12].

Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a suitable ML model. This can range from traditional methods like Random Forest or Support Vector Machines to deep learning architectures such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for ligands and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for protein structures.

- Training: Split the curated dataset into training, validation, and hold-out test sets. Train the model on the training set to learn the mapping from input features to interaction strength.

- Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation and the hold-out test set to evaluate model performance and prevent overfitting. Key metrics include Area Under the Curve (AUC), precision, and recall [12] [21].

Deployment and Screening:

Protocol: Constructing a Digital Twin for Simulated Clinical Trials

Objective: To create a virtual patient population that simulates disease progression and response to therapy, enabling in silico clinical trials.

Workflow:

Data Integration:

Model Architecture Development:

- Develop a multi-scale, mechanistic model that captures the essential biology of the disease. This may include intracellular signaling pathways, inter-cellular communication, and organ-level physiology.

- Calibration: Use the aggregated data to calibrate the model's parameters so that its baseline behavior accurately reflects the natural history of the disease.

Generation of Virtual Patient Cohort:

- Introduce physiological variability into the model parameters (e.g., genetic expression levels, metabolic rates) to generate a diverse synthetic population of thousands of "digital twins" that mirrors the heterogeneity of a real patient population [15].

Simulation of Interventions:

- Virtual Dosing: Simulate the administration of a drug candidate to the virtual cohort, modeling its pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD).

- Outcome Analysis: Run the simulation to predict clinical outcomes (e.g., tumor shrinkage, biomarker change, survival) for each digital twin across different dosing regimens.

Analysis and Trial Optimization:

- Analyze the simulation results to identify patient subgroups most likely to respond, predict potential adverse events, and optimize trial design (e.g., patient stratification, endpoint selection, dosing schedule) before initiating a costly real-world clinical trial [15].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core logical workflows and system relationships described in this guide.

Diagram 1: Conceptual framework linking biological data and computational power to in-silico methods and drug discovery outcomes.

Diagram 2: Standard workflow for AI-driven drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction and virtual screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The modern in silico lab relies on a suite of computational "reagents" and platforms to conduct research.

Table: Key Computational Tools and Platforms for In-Silico Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Example Platforms & Databases | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Database [19] [20] | Provides 3D structural data of target proteins for molecular docking and structure-based drug design. |

| Compound Libraries | PubChem, ZINC [12] | Curated collections of small molecules for virtual screening and lead discovery. |

| AI-Driven Discovery Platforms | Schrodinger Suite, Insilico Medicine Platform, Lilly TuneLab [19] [17] | Integrated software suites that provide AI-powered tools for target ID, molecule generation, and property prediction. |

| Workflow Management & Reproducibility | Nextflow (Seqera Labs), Galaxy, Code Ocean [20] | Platforms that automate, manage, and containerize computational analyses to ensure reproducibility and scalability. |

| Cloud & HPC Providers | AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure [21] [18] [20] | Provide on-demand, scalable computational resources (CPUs, GPUs, storage) necessary for large-scale data analysis. |

| Collaborative Research Platforms | Pluto Biosciences [20] | Interactive platforms for visualizing, analyzing, and sharing complex biological data with collaborators. |

| Toxicity & ADMET Prediction | ProTox-3.0, ADMETlab [15] | Online tools and software for predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity of candidate molecules early in the pipeline. |

The synergy between the explosion of biological data and advancements in computational power is fundamentally rewriting the rules of academic drug discovery. The rise of validated in silico methods—from AI-powered DTI prediction to the use of digital twins for trial simulation—represents a paradigm shift toward a more efficient, cost-effective, and personalized approach to therapeutics development [15]. For academic researchers, embracing this toolkit is no longer optional but essential to remain at the forefront of scientific innovation. The future will be shaped by continued investment in computational infrastructure, the development of more sophisticated and interpretable AI models, and a deepening collaboration between computational and experimental biologists to translate digital insights into real-world therapies.

The field of computer-aided drug design (CADD) has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from a specialized computational support tool into a driver of autonomous discovery. This whitepaper details this evolution within the context of academic drug discovery, tracing the journey from early structure-based design to contemporary artificial intelligence (AI) platforms that can predict, generate, and optimize drug candidates with increasing independence. We provide a technical overview of core methodologies, present structured quantitative data on market and technological trends, and detail experimental protocols for implementing these approaches. Finally, we outline the essential computational toolkit and emerging frontiers that are shaping the future of in silico drug research.

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) refers to the use of computational techniques and software tools to discover, design, and optimize new drug candidates [22]. It integrates bioinformatics, cheminformatics, molecular modeling, and simulation to accelerate drug discovery processes, reduce costs, and improve the success rates of new therapeutics [22]. The field has progressively evolved from a supportive role—aiding in the visualization of protein structures and calculation of simple properties—to a central, generative function in the drug discovery pipeline.

The driving force behind this evolution is the crippling inefficiency of traditional drug development. The conventional process takes 12-15 years to develop a novel drug at an average cost of $2.6 billion, with a probability of success for a drug candidate entering clinical trials of only about 10% [22] [23]. CADD methodologies address these challenges by enabling researchers to expedite the drug discovery and development process, predict pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of compounds, and anticipate potential issues related to novel drug compounds in silico—thereby increasing the chance of a drug entering clinical trial [22].

Table 1: Key Market Segments and Growth in the CADD Landscape (2024-2034)

| Category | Dominant Segment (2024 Share) | Highest Growth Segment | Primary Growth Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Market | North America (45%) [22] | Asia-Pacific [22] | Increased R&D spending & government initiatives [22] |

| Design Type | Structure-Based Drug Design (55%) [22] | Ligand-Based Drug Design [22] | Cost-effectiveness & availability of large ligand databases [22] |

| Technology | Molecular Docking (~40%) [22] | AI/ML-based Drug Design [22] | Ability to analyze vast datasets and improve prediction accuracy [23] |

| Application | Cancer Research (35%) [22] | Infectious Diseases [22] | Rising antimicrobial resistance & need for rapid antiviral discovery [22] |

| End User | Pharmaceutical & Biotech Companies (~60%) [22] | Academic & Research Institutes [22] | Increased funding and academic-industry collaborations [22] |

| Deployment | On-Premise (~65%) [22] | Cloud-Based [22] | Advancements in connectivity and remote access benefits [22] |

From Classical CADD to AI-Driven Discovery

The foundational approaches of CADD are divided into two primary categories: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD). These methodologies formed the cornerstone of early computational drug discovery.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

SBDD relies on the availability of the three-dimensional structure of a biological target, typically determined through X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-EM. The core principle is to use the target's structure to design molecules that bind with high affinity and selectivity [22]. The dominant technology within SBDD is molecular docking, which involves computationally predicting the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein [22]. Docking programs essentially assess the binding efficacy of drug compounds with the target and play a vital role in making drug discovery faster, cheaper, and more effective [22].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

When the 3D structure of a target is unknown, LBDD provides a powerful alternative. This approach uses the known properties of active ligands to design new candidates. Methods include Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, which correlates measurable molecular properties (descriptors) with biological activity, and pharmacophore modeling, which identifies the essential steric and electronic features responsible for a molecule's biological interaction [22]. LBDD is comparatively cost-effective as it does not require complex software to determine protein structure and benefits from the availability of large ligand databases [22].

The AI and Machine Learning Revolution

The inflection point in CADD's evolution has been the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). AI/ML-based drug design is now the fastest-growing technology segment in CADD [22]. AI refers to the intelligence demonstrated by machines, and in the pharmaceutical context, it uses data, computational power, and algorithms to enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and success rates of drug research [24].

AI's impact is multifaceted. It automates the process of drug design by analyzing vast amounts of data to screen a large number of compounds, enabling researchers to identify the most active and effective drug candidates from a large dataset [22]. AI and ML can also predict properties of novel compounds, allowing researchers to develop drugs with higher efficacy and fewer side effects [22]. Key applications include:

- Target Identification: AI can sift through vast amounts of biological data (genomics, proteomics) to uncover potential drug targets that might otherwise go unnoticed [25].

- Molecular Generation: Generative AI and generative adversarial networks (GANs) can design novel molecular structures that meet specific biological and physicochemical criteria, creating new chemical entities de novo [23] [24].

- Property Prediction: Deep learning models can accurately forecast the physicochemical properties, biological activities, and binding affinities of new chemical entities, drastically shortening the candidate identification process [23].

- Clinical Trial Optimization: AI enhances clinical trials by improving patient recruitment through the analysis of Electronic Health Records (EHRs), enabling more adaptive trial designs, and providing real-time data analysis [23] [25].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a modern, AI-integrated drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to lead optimization.

Quantitative Impact: Data on Efficiency Gains

The integration of AI and advanced in silico methods is delivering measurable improvements in the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of drug discovery. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from recent market analyses and scientific reviews.

Table 2: Measurable Impact of AI and Advanced CADD on Drug Discovery

| Metric | Traditional Workflow | AI/Advanced CADD Workflow | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Preclinical Candidate | ~5 years | 12 - 18 months | [25] |

| Cost to Preclinical Candidate | Base Cost | 30% - 40% reduction | [25] |

| Probability of Clinical Success | ~10% | Increased (AI identifies promising candidates earlier) | [25] |

| Market Value of AI in Pharma | - | Projected $16.49 Billion by 2034 | [25] |

| Annual Value for Pharma Sector | - | $350 - $410 Billion (projected by 2025) | [25] |

| Molecule Design Time | Months/Years | Exemplar Case: 21 days (Insilico Medicine) | [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Academic Research

This section provides detailed methodologies for key in silico experiments, designed to be implemented in an academic research setting.

Protocol: Structure-Based Virtual Screening with Molecular Docking

Objective: To identify potential hit compounds from a large chemical library by predicting their binding pose and affinity to a known protein target structure.

Materials & Software:

- Target Protein Structure: From Protein Data Bank (PDB) or predicted via AlphaFold [23] [24].

- Compound Library: e.g., ZINC database (commercially available compounds) or in-house virtual library.

- Docking Software: AutoDock Vina, Schrödinger Glide, or similar.

- Computer Hardware: Multi-core CPU workstation or high-performance computing (HPC) cluster.

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation:

- Download the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., PDB ID: 1ABC).

- Using the docking software's preparation module, remove water molecules and heteroatoms not involved in binding.

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign correct protonation states to residues (e.g., HIS, ASP, GLU) at physiological pH.

- Optimize the structure using energy minimization to relieve steric clashes.

Ligand Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structures of compounds from the database.

- Generate likely tautomers and protonation states at pH 7.4.

- Perform a conformational search to ensure a low-energy starting conformation.

Define the Binding Site:

- If the native ligand co-crystal structure is available, define the grid box centered on this ligand.

- If not, use literature or mutational data to define the key residues of the active site. The grid box should be large enough to accommodate the ligands but not so large as to drastically increase computation time.

Perform Docking:

- Run the docking simulation for each ligand in the library against the prepared protein.

- Set parameters to generate multiple poses per ligand.

- The output will be a ranked list of compounds based on the docking score (an empirical estimate of binding affinity).

Post-Docking Analysis:

- Visually inspect the top-ranked poses to check for sensible interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking).

- Cluster results based on chemical similarity and binding mode.

- Select the top 50-100 compounds for subsequent in vitro validation.

Protocol: Ligand-Based Virtual Screening using QSAR

Objective: To predict the activity of new compounds using a model built from known active and inactive compounds.

Materials & Software:

- Chemical Dataset: A set of molecules with known biological activity (e.g., IC50, Ki).

- Cheminformatics Software: RDKit, OpenBabel, or commercial platforms like Schrödinger.

- Machine Learning Library: Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, or PyTorch.

Procedure:

- Curate the Training Set:

- Assemble a dataset of chemical structures and their corresponding biological activity values.

- Ensure chemical diversity and a wide range of activity potencies.

- Divide the dataset randomly into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%).

Calculate Molecular Descriptors:

- For each molecule, compute a set of numerical descriptors that capture structural and physicochemical properties. These can include:

- 1D: Molecular weight, logP, number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors.

- 2D: Topological indices, fingerprint bits (e.g., ECFP4).

- 3D: Molecular surface area, polarizability.

- For each molecule, compute a set of numerical descriptors that capture structural and physicochemical properties. These can include:

Model Building and Training:

- Use the training set descriptors as input features (X) and the activity data as the output (Y).

- Train a machine learning model, such as a Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), or a Neural Network, to learn the relationship between the descriptors and the activity.

Model Validation:

- Use the held-out test set to evaluate the model's predictive power.

- Calculate performance metrics such as R² (for continuous data) or ROC-AUC (for classification tasks).

Virtual Screening:

- Apply the validated QSAR model to a large database of unknown compounds.

- The model will predict the activity for each compound, allowing you to prioritize those predicted to be most active for further experimental testing.

Protocol: Validating Computational Predictions with CETSA

Objective: To experimentally confirm computational predictions of target engagement in a physiologically relevant cellular context.

Materials:

- Test Compound: The hit compound identified from virtual screening.

- Cell Line: Relevant cell line expressing the target protein.

- Antibody: Specific antibody for the target protein for Western Blotting.

- Equipment: Thermal cycler or heating block, centrifuge, Western Blot or MS instrumentation.

Procedure:

- Compound Treatment: Treat separate aliquots of cells with either your test compound or a DMSO vehicle control for a predetermined time.

- Heat Denaturation: Subject the compound-treated and control cell aliquots to a range of elevated temperatures (e.g., 37°C to 65°C) for 3 minutes.

- Cell Lysis and Fractionation: Lyse the heated cells and separate the soluble (non-denatured) protein fraction from the insoluble (denatured) aggregates by high-speed centrifugation.

- Protein Quantification: Use Western Blotting or quantitative mass spectrometry to measure the amount of target protein remaining in the soluble fraction at each temperature.

- Data Analysis: Compounds that bind and stabilize the target protein will shift its melting curve (( T_m )) to a higher temperature compared to the DMSO control. This provides direct, functional evidence of target engagement within intact cells, validating the in silico predictions [6].

The following diagram maps this critical validation workflow, which connects computational predictions to experimental confirmation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Infrastructure

Successful implementation of a modern CADD pipeline requires a combination of software, data, and computational resources. The following table details the key components of the in silico researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Infrastructure for AI-Driven Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Provides experimentally determined and AI-predicted 3D protein structures for SBDD. |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, ChEMBL, PubChem | Curated collections of commercially available or bioactive molecules for virtual screening. |

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, Schrödinger Glide, UCSF DOCK | Predicts the binding orientation and affinity of a small molecule to a protein target. |

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | RDKit, OpenBabel | Open-source programming toolkits for manipulating molecular structures, calculating descriptors, and building QSAR models. |

| AI/ML Platforms | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Libraries for building and training custom machine learning and deep learning models for molecular property prediction and generation. |

| Specialized AI Drug Discovery Platforms | Atomwise, Insilico Medicine's Chemistry42, Exscientia's Centaur Chemist | End-to-end platforms that often integrate target identification, molecular generation, and optimization using advanced AI. |

| Computational Hardware | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Clusters, Cloud Computing (AWS, Azure, GCP), GPUs | Provides the necessary processing power for computationally intensive tasks like molecular dynamics and deep learning. |

| Validation Assays | CETSA, Cellular Activity Assays | Functional, experimental methods to confirm computational predictions of target engagement and biological activity. |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The trajectory of CADD points toward increasingly autonomous discovery systems, but significant challenges remain. A key roadblock is the generalizability gap in machine learning models, where models can fail unpredictably when they encounter chemical structures or protein families not present in their training data [26]. Research is addressing this by developing more specialized model architectures that learn the fundamental principles of molecular binding rather than relying on shortcuts in the data [26].

The regulatory landscape is also evolving to embrace in silico methods. The FDA's recent landmark decision to phase out mandatory animal testing for many drug types signals a paradigm shift toward accepting computational evidence [15]. This is further supported by the rise of digital twins—virtual patient models that integrate multi-omics data to simulate disease progression and therapeutic response with remarkable accuracy, enabling more personalized and efficient trial designs [15].

However, to fully realize this future, the field must overcome hurdles related to data quality, model interpretability ("black-box" problem), and the development of robust, standardized validation frameworks for in silico protocols [23] [15]. As these challenges are addressed, the integration of AI and computational methods will become not just an advantage, but an indispensable component of academic and industrial drug discovery. Failure to employ these methods may soon be seen as a significant strategic oversight [15].

Market Outlook and Growth Potential of In Silico Technologies

The pharmaceutical industry is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the integration of in silico technologies—computational methods that simulate, model, and predict biological systems and drug interactions. These approaches have become indispensable tools for addressing the formidable challenges of traditional drug discovery, including escalating costs, lengthy timelines, and high failure rates. The global in-silico drug discovery market, valued between USD 4.17 billion and USD 4.38 billion in 2025, is projected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 11.09% to 13.60%, reaching approximately USD 10.73 billion to USD 12.15 billion by 2032-2034 [17] [27]. This growth trajectory underscores a fundamental shift toward computational-first strategies in academic and industrial research, enabling researchers to prioritize drug candidates more efficiently, reduce reliance on costly wet-lab experiments, and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics for complex diseases.

Market Landscape and Growth Dynamics

Current Market Size and Projected Growth

The in-silico drug discovery market exhibits robust growth globally, fueled by technological advancements and increasing adoption across pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors. Table 1 summarizes the key market metrics and projections from leading industry analyses.

Table 1: Global In-Silico Drug Discovery Market Outlook

| Market Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2032/2034 Projection | CAGR | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2025) | USD 4.17 billion | USD 10.73 billion (2034) | 11.09% | Precedence Research [17] |

| Market Size (2024) | USD 4,380.97 billion | USD 12,150.59 billion (2032) | 13.60% | Data Bridge Market Research [27] |

| Related Clinical Trials Market | USD 3.95 billion | USD 6.39 billion (2033) | 5.5% | DataM Intelligence [28] |

This growth is primarily driven by the escalating costs of traditional drug development, which now surpass USD 2.3-2.8 billion per approved drug, coupled with clinical attrition rates approaching 90% [2] [28]. In silico technologies address these challenges by enabling virtual screening, predictive toxicology, and optimized candidate selection, significantly reducing the resource burden during early discovery phases.

Key Market Drivers and Restraints

Market Drivers

- Artificial Intelligence Integration: Generative AI platforms now underpin more than 70 clinical-stage candidates, demonstrating discovery cycles as short as 18 months compared to historical multi-year averages [29]. AI adoption in hit identification is projected to contribute +2.1% to CAGR forecasts [29].

- Cloud-Native High-Performance Computing (HPC): Subscription-based HPC delivered through hyperscale clouds lowers entry barriers for startups and academic institutions, enabling multi-million-compound screens without capital-intensive infrastructure [29].

- R&D Cost Pressures: With the average investment per new molecular entity surpassing USD 2.6 billion in 2024, predictive simulations that curtail late-stage failures offer significant economic advantages [29].

- Regulatory Acceptance Growing: The FDA, EMA, and other regulatory agencies increasingly encourage Model-Informed Drug Development, boosting confidence in in-silico evidence for regulatory submissions [28].

Market Restraints

- High Initial Costs and Expertise Requirements: Advanced in-silico platforms require significant upfront investment and specialized computational chemists, creating barriers for smaller organizations [17] [27]. Industry demand for AI-literate chemists outpaces graduate output, straining project timelines and inflating talent costs [29].

- Model Bias from Legacy Datasets: Historical repositories often under-represent diverse ethnic groups and rare disease phenotypes, risking biased AI outputs that underperform in real-world populations [29].

- Intellectual Property Ambiguity: Regulatory uncertainty persists regarding IP protection for AI-generated molecules, potentially discouraging investment in novel algorithmic approaches [29].

Market Segment Analysis

Analysis by Product Type, End-User, and Workflow

The in-silico drug discovery market exhibits distinct segmentation patterns across product types, end-users, and application workflows. Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of key segments and their market characteristics.

Table 2: In-Silico Drug Discovery Market Segmentation Analysis

| Segment Category | Dominant Segment | Market Share (2024) | Fastest Growing Segment | Growth Rate | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Software as a Service (SaaS) | 40.5%-42.6% | Consultancy as a Service | 23.4% | [17] [27] |

| End User | Pharmaceutical & Biotech Companies | 34.8%-46.78% | Contract Research Organizations (CROs) | 8.42% | [17] [29] |

| Application Workflow | Target Identification | 36.5% | Hit Identification | 7.45% | [17] [29] |

| Therapeutic Area | Oncological Disorders | 32.8%-37% | Neurology | 8.95% | [17] [29] |

| Deployment | Cloud-Based | 67.92% | Cloud-Based | 7.92% | [29] |

The dominance of the SaaS model reflects a structural shift toward cloud-based, collaborative R&D environments that offer scalable, subscription-based access to computational tools without heavy upfront infrastructure investments [17] [27]. Similarly, the prominence of target identification applications underscores the critical role of in silico methods in mining multi-omics repositories to reveal non-obvious therapeutic targets, particularly in complex disease areas like oncology [17] [29].

Geographical Market Analysis

- North America: Dominated the market with a 38%-44% share in 2024, underpinned by robust venture funding, progressive FDA guidance, and concentrated technological expertise [17] [29] [28]. The U.S. alone accounted for USD 1.74 billion in 2024, with over 65% of top pharmaceutical companies routinely using in-silico modeling [28].

- Europe: Maintained significant market presence supported by strong public-sector research and harmonized regulatory frameworks that prioritize animal-free testing alternatives [29].

- Asia-Pacific: Emerged as the fastest-growing region with a CAGR of 8.95%, propelled by China's multi-fold increase in clinical trials, Japan's national AI initiatives, and government-backed digital research infrastructure [17] [29].

Technical Framework: Essential In Silico Methodologies

Core Computational Approaches and Workflows

In silico drug discovery encompasses a diverse toolkit of computational methods that integrate across the drug development pipeline. The diagram below illustrates a generalized workflow for structure-based drug discovery, highlighting key computational stages from target identification to lead optimization.

Successful implementation of in silico methodologies requires access to specialized computational tools, databases, and software platforms. Table 3 catalogs essential "research reagents" in the computational domain that form the foundation of modern in silico drug discovery workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for In Silico Drug Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Purpose | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), UniProt, AlphaFold DB | Provide experimentally determined and predicted protein structures for target analysis and modeling | Homology modeling, binding site identification, molecular docking [2] |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, ChEMBL, PubChem | Curate chemical structures and bioactivity data for virtual screening | Lead identification, scaffold hopping, library design [29] [2] |

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock, Schrödinger Suite, Glide | Predict preferred orientation and binding affinity of small molecules to target receptors | Virtual screening, binding mode analysis, lead optimization [2] |

| Molecular Dynamics Platforms | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER | Simulate physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to study dynamic behavior | Conformational analysis, binding free energy calculations, mechanism elucidation [2] |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | ADMET Predictor, SwissADME, pkCSM | Forecast absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties | Candidate prioritization, toxicity risk assessment, pharmacokinetic optimization [29] [2] |

| AI/ML-Driven Discovery Platforms | Atomwise, Insilico Medicine, Schrödinger | Apply machine learning and generative algorithms to novel compound design | de novo drug design, hit identification, property prediction [17] [29] |

Experimental Protocol: Structure-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

The following detailed protocol outlines a standard methodology for structure-based virtual screening, a cornerstone technique in in silico drug discovery:

Target Preparation:

- Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling [2]. For targets with no experimental structure, utilize ab initio prediction tools like AlphaFold or RoseTTAFold.

- Process the protein structure by removing water molecules and heteroatoms, adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and optimizing side-chain conformations of unresolved residues.

- Define the binding site coordinates based on known ligand positions from co-crystallized structures or through computational binding site prediction algorithms.

Compound Library Preparation:

- Curate a diverse chemical library from databases such as ZINC, ChEMBL, or in-house collections [2]. For focused libraries, apply drug-like filters (Lipinski's Rule of Five) and remove compounds with undesirable chemical properties or toxicophores.

- Generate three-dimensional conformations for each compound using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF94, GAFF) and energy minimization protocols.

- Standardize tautomeric and protonation states appropriate for physiological pH conditions using tools like OpenBabel or RDKit.

Molecular Docking:

- Execute high-throughput docking simulations using platforms such as AutoDock Vina, Glide, or GOLD [2]. Employ a hierarchical screening approach with rapid rigid-body docking followed by more precise flexible docking for top-ranking compounds.

- Utilize scoring functions (e.g., empirical, force field-based, knowledge-based) to predict binding affinities and rank compounds based on their complementarity to the binding site.

Post-Docking Analysis:

- Cluster docking poses based on spatial similarity and interaction patterns to identify conserved binding modes.

- Analyze protein-ligand interactions for top-ranking compounds, focusing on key hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and salt bridges that contribute to binding affinity and specificity.

- Apply molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) or molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) methods to refine binding free energy estimates for select candidates.

Experimental Validation:

- Prioritize the top 20-50 compounds based on docking scores, interaction profiles, and chemical diversity for in vitro testing.

- Procure or synthesize selected compounds and evaluate their biological activity using target-specific assays (e.g., enzymatic inhibition, cell-based viability assays).

- Iteratively optimize hit compounds through structural analog screening and structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis.

Emerging Technologies and Future Outlook

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Transformations

AI and machine learning are fundamentally reshaping the in silico technology landscape, moving beyond supplementary tools to become central drivers of innovation. Generative AI approaches can now design novel molecular structures with desired properties, exploring chemical spaces that were previously computationally prohibitive [17]. The launch of platforms like Lilly's TuneLab, which provides access to AI models trained on proprietary data representing over USD 1 billion in research investment, demonstrates the growing strategic value of AI in pharmaceutical R&D [17]. These technologies are particularly impactful in oncology, where AI can interrogate complex tumor heterogeneity to surface previously "undruggable" pathways [29].

Quantum Computing and Advanced Simulation

The next inflection point in in silico technologies will likely come from the integration of quantum computing with traditional computational approaches. Quantum-ready workflows are already demonstrating capabilities to deliver thousands of viable leads against cancer proteins in silico, highlighting their potential to further accelerate discovery timelines [29]. Major pharmaceutical companies are now earmarking up to USD 25 million annually for quantum-computing pilots, betting that sub-angstrom accuracy will significantly de-risk drug development pipelines [29].

In-Silico Clinical Trials and Regulatory Science

The adoption of in-silico clinical trials represents a paradigm shift in drug development, with the market projected to reach USD 6.39 billion by 2033 [28]. These approaches utilize virtual patient simulations, digital twins, and AI-powered predictive systems to model drug responses across diverse patient subpopulations, reducing the need for extensive human trials [28]. Regulatory agencies are increasingly accepting these computational methods, with the FDA's Model-Informed Drug Development pilot program participation increasing 23% year-over-year from 2023-2024 [28]. This trend toward regulatory acceptance of in silico evidence is expected to accelerate, potentially leading to model-based approvals for certain therapeutic categories.

The expanding market footprint and rapid technological evolution of in silico technologies present strategic opportunities for academic drug discovery research. The convergence of AI-driven design, cloud-based infrastructure, and regulatory acceptance is creating an environment where academic institutions can compete effectively in early-stage drug discovery. By leveraging SaaS platforms and collaborative AI tools, researchers can access sophisticated computational capabilities without prohibitive capital investment [17] [27].

For academic research programs, success will depend on developing interdisciplinary teams that bridge computational and biological domains, addressing the critical shortage of computational chemists that currently constrains industry growth [29]. Additionally, focus on underrepresented disease areas and diverse population data can help mitigate the model bias issues that affect many legacy datasets [29]. As in silico methodologies continue to mature, their integration into academic research workflows promises to enhance productivity, foster innovation, and accelerate the translation of basic research discoveries into therapeutic candidates that address unmet medical needs.

In Silico Toolbox: Core Methods and Workflow Integration from Target to Candidate

The identification and validation of drug targets is a foundational step in the drug discovery pipeline, profoundly influencing the probability of success in subsequent development stages. Traditional methods, which often rely on high-throughput screening, molecular docking, and hypothesis-driven studies based on existing literature, are increasingly constrained by biological complexity, data fragmentation, and limited scalability [30]. These conventional approaches are not only time-consuming and costly but also struggle to capture the intricate, system-level mechanisms of disease pathogenesis [31]. In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force, reshaping target discovery through data-driven, mechanism-aware, and system-level inference [30]. By leveraging large-scale biomedical datasets, AI enables the integration of multimodal data—such as genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles—to perform comprehensive analyses that were previously unattainable [32].

The core challenge in modern therapeutic innovation lies in pinpointing critical biomolecules that act as key regulators in disease pathways. A drug target, typically a protein, gene, or other biomolecule, must have a demonstrable role in the disease, limited function in normal physiology, and be "druggable"—susceptible to modulation by a therapeutic compound [31]. However, the pool of empirically validated drug targets remains surprisingly small, with fewer than 500 confirmed targets globally as of 2022 [33]. This limitation underscores the urgent need for more efficient and accurate target discovery strategies. AI, particularly when applied to multi-omics data, offers a pathway to overcome these limitations by providing a holistic view of biological systems, thereby accelerating the identification of novel, therapeutically relevant targets and enhancing the validation process [32] [34].

AI Methodologies for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Multi-omics data integration combines information from various molecular layers—such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to construct a comprehensive picture of cellular activity and disease mechanisms. The power of multi-omics lies in its ability to reveal interactions and causal relationships that are invisible to single-omics approaches [34]. For instance, while genomics can identify disease-associated mutations, integrating transcriptomics and proteomics can distinguish causal mutations from inconsequential ones by revealing their downstream functional impacts [34]. The integration of these diverse datasets, however, presents significant computational challenges due to data heterogeneity, high dimensionality, and noise [32] [35]. AI provides a robust set of tools to navigate this complexity.

Data Integration Strategies and AI Architectures

Several computational strategies have been developed for multi-omics integration, each with distinct strengths for specific biological questions. The table below summarizes the primary approaches and the AI models that leverage them.

Table 1: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies and Corresponding AI Models

| Integration Strategy | Description | Key AI Models & Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Integration | Links omics data via shared biological concepts (e.g., genes, pathways) using existing knowledge bases [32]. | Knowledge graphs; Large Language Models (LLMs) for literature mining [30] [33]. |

| Statistical Integration | Combines or compares datasets using quantitative measures like correlation, regression, or clustering [32]. | Standard machine learning (e.g., SVMs, Random Forests); Principal Component Analysis [32] [31]. |

| Model-Based Integration | Uses mathematical models to simulate system behavior and predict outcomes of perturbations [32]. | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs); Causal inference models; Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models [30] [32]. |

| Network-Based Integration | Represents biological entities as nodes and their interactions as edges in a network, providing a systems-level view [35]. | Network propagation; GNNs; Network inference models [30] [35]. |