A Practical Guide to ADMET Prediction: Choosing the Right Evaluation Metrics for Classification and Regression Models

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating machine learning models that predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties.

A Practical Guide to ADMET Prediction: Choosing the Right Evaluation Metrics for Classification and Regression Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating machine learning models that predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational metrics, advanced methodological applications, troubleshooting for common pitfalls like data imbalance and out-of-distribution generalization, and rigorous validation strategies. By synthesizing current benchmarking practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build more reliable, robust, and clinically relevant in silico ADMET models, ultimately improving the efficiency of drug discovery pipelines.

Core Metrics and Principles: Building a Foundation for ADMET Model Evaluation

The evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a fundamental bottleneck in modern drug discovery, directly influencing both the success rate and efficiency of therapeutic development. Despite technological advances, drug development remains a highly complex, resource-intensive endeavor with substantial attrition rates [1]. According to recent analyses, approximately 40-45% of clinical attrition continues to be attributed to ADMET liabilities, with poor bioavailability and unforeseen toxicity representing major contributors to late-stage failures [2] [1]. This review systematically examines the critical role of ADMET evaluation in mitigating drug development risks, with particular focus on benchmarking methodologies, comparative performance of predictive models, and experimental protocols that are reshaping preclinical decision-making.

The transition from traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) methods to machine learning (ML) approaches has transformed ADMET prediction by enabling more accurate assessment of complex structure-property relationships [3] [1]. However, the field continues to grapple with challenges of data quality, model interpretability, and generalizability across diverse chemical spaces [4] [5]. By examining current state-of-the-art methodologies and their validation frameworks, this analysis aims to provide researchers and drug development professionals with actionable insights for selecting and implementing ADMET prediction strategies that can meaningfully reduce late-stage attrition.

The Growing Arsenal of Machine Learning Approaches for ADMET Prediction

The landscape of ADMET prediction has evolved significantly beyond traditional QSAR methods, with diverse machine learning architectures now demonstrating compelling performance across various endpoints. Graph neural networks (GNNs), particularly message-passing neural networks (MPNNs) as implemented in Chemprop, have shown strong capabilities in modeling local molecular structures through their message-passing mechanisms between nodes and edges [6] [5]. Meanwhile, Transformer-based architectures like MSformer-ADMET leverage self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies and global semantics within molecules, addressing limitations of graph-based models in representing global chemical context [6].

Comparative studies indicate that ensemble methods and multitask learning frameworks consistently outperform single-task approaches by leveraging shared representations across related endpoints [1] [2]. The emerging paradigm of federated learning enables model training across distributed proprietary datasets without centralizing sensitive data, systematically expanding model applicability domains and improving robustness for predicting unseen scaffolds and assay modalities [2]. These architectural advances are complemented by progress in molecular representations, where fragment-based approaches like those in MSformer-ADMET provide more chemically meaningful structural representations compared to traditional atom-level encodings [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Major ML Approaches for ADMET Prediction

| Model Architecture | Key Strengths | Common Applications | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (e.g., Chemprop) | Strong local structure modeling; effective in multitask settings | Solubility, permeability, toxicity endpoints | Limited substructure interpretability |

| Transformer-based Models (e.g., MSformer-ADMET) | Captures long-range dependencies; global molecular context | Multitask ADMET endpoints; metabolism prediction | Fragment-level attention provides structural insights |

| Ensemble Methods (Random Forests, Gradient Boosting) | Robust to noise; performs well with limited data | Classification tasks (e.g., hERG inhibition) | Feature importance analysis available |

| Multitask Deep Learning | Leverages correlated endpoints; reduces overfitting | Comprehensive ADMET profiling | Varies by implementation |

| Federated Learning | Expands chemical coverage; preserves data privacy | Cross-pharma collaborative models | Similar to base architecture |

Benchmarking Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating ADMET prediction models, yet standardized methodologies remain challenging due to dataset heterogeneity and varying experimental protocols. Recent initiatives have established more structured approaches to model validation, emphasizing statistical significance testing and practical applicability assessment.

Data Curation and Preprocessing Standards

High-quality ADMET prediction begins with systematic data curation. The field is moving beyond conventionally combined public datasets toward more carefully cleaned and standardized data sources [4]. Essential data cleaning procedures include:

- SMILES Standardization: Consistent representation of compound structures using tools like the standardisation tool by Atkinson et al., with modifications to include boron and silicon in organic elements lists [4]

- Salt Removal: Elimination of records pertaining to salt complexes, particularly critical for solubility datasets where different salts of the same compound may exhibit varying properties [4]

- De-duplication Protocol: Removal of inconsistent measurements where duplicate compounds show conflicting target values, with consistency defined as exactly the same for binary tasks or within 20% of the inter-quartile range for regression tasks [4]

- Parent Compound Extraction: Isolation of organic parent compounds from salt forms to attribute effects to the parent compound [4]

The Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) has emerged as a valuable resource, providing curated benchmarks for ADMET-associated properties, though concerns about data cleanliness persist [4]. Emerging initiatives like OpenADMET aim to address these limitations by generating consistently measured, high-quality experimental data specifically for model development [7].

Model Evaluation Frameworks

Robust model assessment requires going beyond conventional hold-out testing. Current best practices incorporate:

- Cross-validation with Statistical Hypothesis Testing: Combining cross-validation with statistical tests to add reliability to model comparisons and distinguish genuine performance improvements from random noise [4] [2]

- Scaffold-based Splitting: Evaluating model performance on structurally distinct compounds to better simulate real-world generalization requirements [4]

- External Validation: Assessing models trained on one data source against test sets from different sources for the same property [4]

- Blind Challenges: Prospective evaluation where teams predict properties for compounds not previously seen, following the tradition of community efforts like CASP [7] [8]

The integration of these evaluation methods provides a more comprehensive assessment of model performance, particularly regarding generalizability to novel chemical scaffolds—a critical requirement for practical drug discovery applications.

Performance Comparison Across ADMET Endpoints

Comparative studies reveal significant variation in model performance across different ADMET endpoints, with optimal approaches often being task-dependent. Systematic benchmarking across multiple endpoints provides insights into the relative strengths of various methodologies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ML Models on Key ADMET Endpoints

| ADMET Endpoint | Best-Performing Model | Key Metric | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | MSformer-ADMET | RMSE | Superior to traditional QSAR and graph-based models [6] |

| Permeability | Ensemble Methods (RF/LightGBM) | Accuracy | Classical descriptors with tree-based methods perform well [4] |

| hERG Inhibition | Multitask Deep Learning | AUC-ROC | Benefits from correlated toxicity endpoints [1] |

| CYP450 Inhibition | Federated Learning Models | Precision | Cross-pharma data diversity improves generalization [2] |

| Metabolic Clearance | Graph Neural Networks | MAE | Message-passing mechanisms capture metabolic transformations [6] |

| Toxicity Endpoints | Transformer-based Models | Balanced Accuracy | Fragment-level interpretability aids structural alert identification [6] |

The Polaris ADMET Challenge results demonstrated that multi-task architectures trained on broader and better-curated data consistently outperformed single-task or non-ADMET pre-trained models, achieving 40-60% reductions in prediction error across endpoints including human and mouse liver microsomal clearance, solubility, and permeability [2]. This highlights that data diversity and representativeness, rather than model architecture alone, are dominant factors driving predictive accuracy and generalization.

Experimental evidence indicates that model performance improvements scale with data diversity, with federated learning approaches consistently outperforming local baselines as the number and diversity of participants increases [2]. This relationship underscores the critical importance of expanding chemical space coverage in training data, whether through centralized curation or privacy-preserving distributed learning approaches.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The advancement of ADMET prediction relies on both experimental assays and computational infrastructure. The following table details key resources driving progress in the field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ADMET Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Data Resource | Curated benchmarks for ADMET-associated properties | Provides standardized datasets for model training and validation [4] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Generation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Enables featurization for classical ML models [4] |

| OpenADMET | Experimental & Computational Initiative | Generation of high-quality ADMET data and models | Addresses data quality issues in literature datasets [7] |

| Chemprop | Deep Learning Framework | Message-passing neural networks for molecular property prediction | Widely used benchmark for graph-based ADMET models [4] [5] |

| Apheris Federated ADMET Network | Federated Learning Platform | Cross-organizational model training without data sharing | Enables expanding chemical coverage while preserving IP [2] |

| ADMETlab | Predictive Platform | Toxicity and pharmacokinetic endpoint prediction | Established benchmark with multi-task learning capabilities [3] [5] |

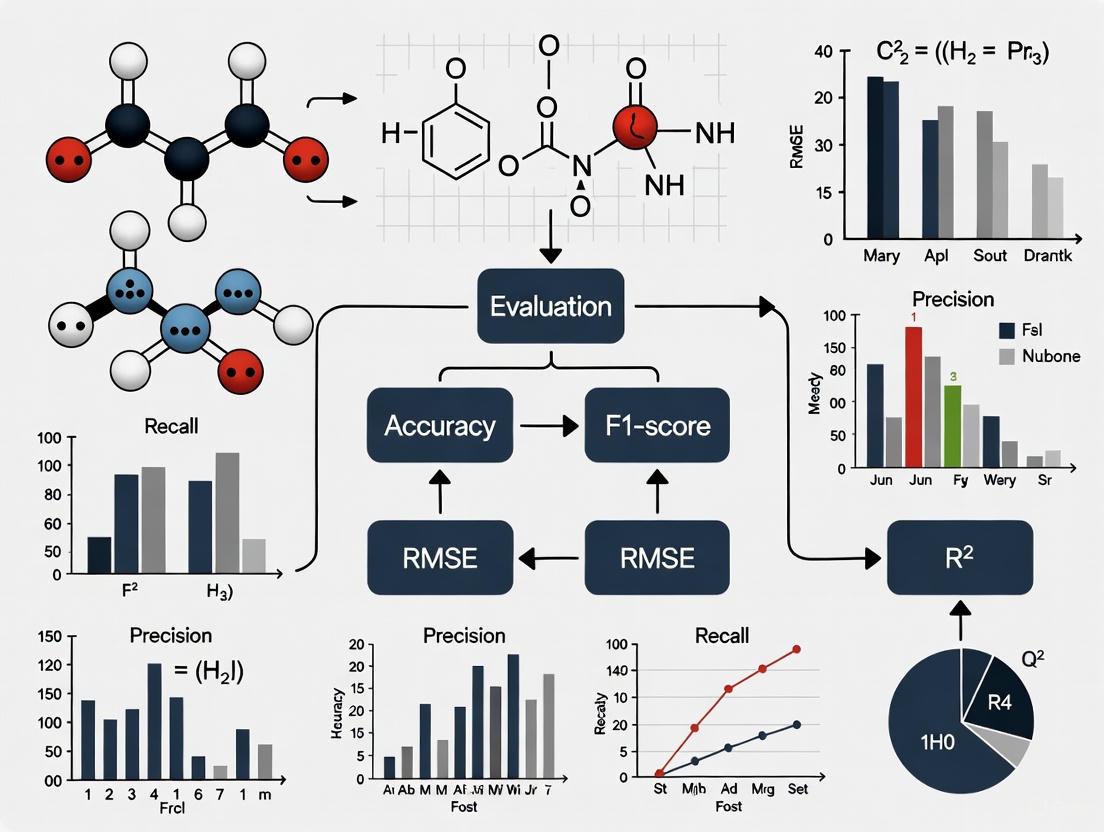

ADMET Prediction Workflow and Model Selection Framework

Implementing effective ADMET prediction requires a systematic approach from data preparation to model deployment. The following workflow diagram illustrates key decision points and methodologies.

The evolving landscape of ADMET prediction demonstrates a clear trajectory from traditional QSAR methods toward more sophisticated, data-driven machine learning approaches that offer genuine potential to reduce drug development attrition. The critical success factors emerging across studies emphasize data quality and diversity over algorithmic complexity, with multi-task architectures trained on broad, well-curated datasets consistently achieving superior performance [4] [2]. The establishment of rigorous benchmarking initiatives and blind challenges provides the necessary framework for transparently evaluating model performance and driving meaningful progress [7] [8].

For researchers and drug development professionals, strategic implementation of ADMET prediction requires careful consideration of several factors: the representativeness of training data relative to target chemical space, the interpretability requirements for specific decision contexts, and the integration of complementary data modalities to enhance predictive robustness. As regulatory agencies increasingly recognize the value of AI-based toxicity models within their New Approach Methodologies frameworks [5], the development of validated, transparent ADMET prediction tools will become increasingly central to efficient drug discovery. By advancing these computational approaches alongside high-quality data generation initiatives, the field moves closer to realizing the promise of predictive ADMET evaluation to systematically reduce late-stage failures and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

The evaluation of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties constitutes a critical bottleneck in drug discovery, with poor ADMET profiles contributing significantly to the high attrition rate of drug candidates during clinical development [3] [1]. Accurate early-stage prediction of these properties is essential for reducing late-stage failures, lowering development costs, and accelerating the entire drug discovery process [1] [9]. The convergence of artificial intelligence with pharmaceutical sciences has revolutionized biomedical research, enabling the development of computational models that can predict ADMET characteristics with increasing accuracy [6] [10].

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches have emerged as transformative tools for ADMET prediction, offering rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible alternatives that integrate seamlessly with existing drug discovery pipelines [3]. These approaches range from classical models using fixed molecular fingerprints to advanced graph neural networks and transformer architectures that learn representations directly from molecular structure [6] [11]. A fundamental aspect of developing these predictive models is the appropriate formulation of the learning task—specifically, whether an ADMET endpoint should be framed as a classification problem (predicting categorical labels) or a regression problem (predicting continuous values)—as this decision directly impacts model selection, evaluation metrics, and practical utility in lead optimization [4] [12].

This guide examines the task definition for key ADMET endpoints within the broader context of evaluation metrics for ADMET classification and regression models, providing researchers with a structured framework for selecting appropriate modeling approaches based on property characteristics, data availability, and decision-making requirements in drug discovery pipelines.

ADMET Endpoints: Task Formulations and Quantitative Performance

The designation of ADMET endpoints as classification or regression tasks depends on multiple factors, including the nature of the property being predicted, the type of experimental data available, the decision-making context in which the prediction will be used, and conventional practices within the field [13] [11]. Classification models are typically employed when the prediction is used for binary decision-making (e.g., go/no-go decisions in early screening), when experimental data is inherently categorical, or when continuous data has been binned into categories based on established thresholds [1]. In contrast, regression models are preferred when quantitative structure-property relationships are being explored, when precise numerical values are required for pharmacokinetic modeling, or when the continuous nature of the property is essential for compound optimization [4].

Table 1: Task Formulations and Performance Metrics for Key ADMET Endpoints

| ADMET Category | Specific Endpoint | Task Type | Common Evaluation Metrics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Bioavailability | Classification | AUROC | 0.745 ± 0.005 [13] |

| Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA) | Classification | AUROC | 0.984 ± 0.004 [13] | |

| Caco-2 Permeability | Regression | MAE | 0.285 ± 0.005 [13] | |

| Distribution | Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Penetration | Classification | AUROC | 0.919 ± 0.005 [13] |

| Volume of Distribution (VDss) | Regression | Spearman | 0.585 ± 0.0 [13] | |

| Metabolism | CYP450 Inhibition (e.g., CYP3A4) | Classification | AUPRC | 0.882 ± 0.002 [13] |

| CYP450 Substrate (e.g., CYP2D6) | Classification | AUROC | 0.718 ± 0.002 [13] | |

| Toxicity | hERG Inhibition | Classification | AUROC | 0.871 ± 0.003 [13] |

| AMES Mutagenicity | Classification | AUROC | 0.867 ± 0.002 [13] | |

| Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) | Classification | AUROC | 0.927 ± 0.0 [13] | |

| Physicochemical | Lipophilicity (LogP) | Regression | MAE | 0.449 ± 0.009 [13] |

| Aqueous Solubility | Regression | MAE | 0.753 ± 0.004 [13] |

Recent benchmarking studies have revealed that the optimal machine learning approach varies across different ADMET endpoints [4] [11]. For classification tasks, gradient-boosted decision trees (such as XGBoost and CatBoost) and graph neural networks (particularly Graph Attention Networks) have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance, with the latter showing superior generalization to out-of-distribution compounds [11]. For regression tasks, random forests and message-passing neural networks (as implemented in Chemprop) have proven highly effective, especially when combined with comprehensive feature sets that include both classical descriptors and learned representations [4].

The selection of evaluation metrics must align with the task type: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) are standard for classification tasks, particularly with imbalanced datasets, while Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) are appropriate for regression tasks [13] [11]. The Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) and related benchmarking initiatives have been instrumental in standardizing these evaluation protocols across diverse ADMET endpoints [4] [6] [11].

Experimental Protocols and Model Evaluation Frameworks

Data Curation and Preprocessing

Robust ADMET prediction begins with rigorous data curation and preprocessing. Public ADMET datasets are often criticized regarding data cleanliness, with issues ranging from inconsistent SMILES representations and duplicate measurements with varying values to inconsistent binary labels [4]. To mitigate these concerns, researchers implement comprehensive data cleaning protocols including: removal of inorganic salts and organometallic compounds; extraction of organic parent compounds from salt forms; adjustment of tautomers for consistent functional group representation; canonicalization of SMILES strings; and de-duplication with consistency checks [4]. For datasets with highly skewed distributions, appropriate transformations (e.g., log-transformation for clearance and volume of distribution values) are applied to improve model performance [4].

The standard machine learning methodology begins with obtaining suitable datasets from publicly available repositories such as TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons), ChEMBL, and other specialized databases [9]. The quality of data is crucial for successful ML tasks, as it directly impacts model performance. Data preprocessing—including cleaning, normalization, and feature selection—is essential for improving data quality and reducing irrelevant or redundant information [9]. For classification tasks with imbalanced datasets, combining feature selection and data sampling techniques can significantly improve prediction performance [9].

Feature Representation and Molecular Descriptors

Feature engineering plays a crucial role in improving ADMET prediction accuracy. Molecular descriptors—numerical representations that convey structural and physicochemical attributes of compounds—can be calculated from 1D, 2D, or 3D molecular structures using various software tools [9]. Common approaches include:

- Fixed fingerprints: Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP), Avalon, and ErG fingerprints provide fixed-length representations of molecular structure [11].

- Molecular descriptors: RDKit descriptors, Mordred descriptors, and PaDEL descriptors offer comprehensive sets of physicochemical properties [4] [9].

- Learned representations: Graph neural networks learn task-specific features directly from molecular graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [6] [9].

Recent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the impact of feature representation on model performance, with findings indicating that the optimal feature set is often endpoint-specific [4]. While classical descriptors and fingerprints remain highly competitive, graph-based representations have demonstrated superior performance for certain endpoints, particularly when combined with advanced neural network architectures [11].

Model Training and Evaluation Methodologies

Rigorous model evaluation is essential for reliable ADMET prediction. Benchmarking studies employ not only random splits but also scaffold-based, temporal, and molecular weight-constrained splits to assess model generalizability [11]. These rigorous splits enable differentiation between mere memorization and genuine chemical extrapolation in predictive models.

The ADMET Benchmark Group promotes the use of multiple, chemically meaningful metrics, with regression tasks evaluated using MAE, RMSE, and R², while classification tasks are assessed using AUROC, AUPRC, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) [11]. Additionally, studies are increasingly incorporating statistical hypothesis testing alongside cross-validation to enhance the reliability of model comparisons [4].

For a visual representation of the complete experimental workflow for ADMET model development:

Diagram 1: ADMET Model Development Workflow

Successful ADMET prediction requires both computational tools and carefully curated data resources. The following table outlines key resources used in developing and evaluating ADMET models:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for ADMET Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ADMET |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Data Repository | Provides curated benchmark datasets | Standardized ADMET datasets for model training and evaluation [4] [6] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Generates classical features for ML models [4] |

| Chemprop | Deep Learning Framework | Implements message passing neural networks | End-to-end ADMET prediction from molecular graphs [4] |

| MSformer-ADMET | Specialized Model | Transformer architecture for molecular property prediction | State-of-the-art performance across multiple ADMET endpoints [6] |

| MTGL-ADMET | Multi-task Learning Framework | Predicts multiple ADMET endpoints simultaneously | Improves data efficiency for endpoints with limited labels [12] |

| Auto-ADMET | Automated ML Platform | Dynamic pipeline optimization | Adaptable model selection for diverse chemical spaces [11] |

Beyond these computational resources, effective ADMET modeling requires careful consideration of the experimental context in which the training data was generated. Factors such as assay type, experimental conditions, and measurement variability can significantly impact model performance and generalizability [4] [11]. Researchers should prioritize data sources that provide comprehensive metadata and employ consistent experimental protocols throughout the dataset.

For complex multi-task learning approaches that have shown promise in ADMET prediction:

Diagram 2: Multi-task Learning Framework for ADMET

The appropriate formulation of ADMET endpoints as classification or regression tasks is fundamental to developing predictive models that provide genuine utility in drug discovery pipelines. Classification approaches dominate for discrete decision-making contexts such as toxicity risk assessment and categorical metabolic fate predictions, while regression models are preferred for quantitative pharmacokinetic parameters and physicochemical properties that require numerical precision for compound optimization [13].

The evolving landscape of ADMET prediction is characterized by several key trends: the emergence of standardized benchmarking initiatives that enable fair comparison across methods [11]; the increasing adoption of graph neural networks and transformer architectures that learn representations directly from molecular structure [6]; the development of multi-task learning frameworks that improve data efficiency for endpoints with limited labels [12]; and the integration of automated machine learning approaches that adaptively select optimal modeling strategies for specific chemical spaces [11].

As the field advances, challenges remain in improving model interpretability, enhancing generalization to novel chemical domains, and integrating multimodal data sources to better capture the biological complexity underlying ADMET properties [1]. By carefully considering task formulation, feature representation, and evaluation methodology, researchers can develop more reliable ADMET predictors that effectively accelerate the discovery of safer and more efficacious therapeutics.

In the field of computational toxicology and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction, the accurate evaluation of classification models is a critical determinant of their real-world applicability in drug discovery. With approximately 30% of preclinical candidate compounds failing due to toxicity issues, the ability to reliably assess model performance directly impacts development timelines, cost control, and public health safety [14]. Classification tasks in this domain, such as identifying thyroid-disrupting chemicals or predicting CYP enzyme inhibition, frequently encounter the challenge of imbalanced datasets, where inactive compounds significantly outnumber active ones [15]. This imbalance complicates model assessment and necessitates metrics that remain informative under such conditions.

The selection of appropriate evaluation metrics forms the foundation for robust model comparison and advancement. The ADMET Benchmark Group, a framework for systematic evaluation of computational predictors, emphasizes the need for multiple, chemically meaningful metrics to ensure reliable assessment [11]. Among the numerous available metrics, the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), and the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) have emerged as particularly valuable for ADMET classification problems. These metrics provide complementary insights into model performance, with each offering distinct advantages for specific scenarios encountered in pharmaceutical research [16] [15] [17].

Metric Definitions and Mathematical Foundations

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC)

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a graphical plot that illustrates the diagnostic ability of a binary classifier system by plotting the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) at various threshold settings. The Area Under this Curve (AUROC) provides a aggregate measure of performance across all possible classification thresholds. The AUROC value ranges from 0 to 1, where a perfect classifier achieves an AUROC of 1, while a random classifier scores 0.5. Mathematically, the True Positive Rate (also called sensitivity or recall) is calculated as TPR = TP/(TP+FN), and the False Positive Rate is FPR = FP/(FP+TN), where TP, FP, TN, and FN represent True Positives, False Positives, True Negatives, and False Negatives, respectively [17].

A key characteristic of AUROC is its robustness to class imbalance. Recent research has demonstrated that the ROC curve and its associated area are invariant to changes in the class distribution, meaning that the AUROC value remains consistent regardless of the ratio between positive and negative instances in the dataset. This property makes AUROC particularly valuable for comparing models across different datasets with varying class imbalances, a common scenario in ADMET research where the proportion of toxic to non-toxic compounds can differ significantly across endpoints [17].

Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC)

The Precision-Recall (PR) curve is an alternative to the ROC curve that plots precision against recall (TPR) at different classification thresholds. Precision, defined as TP/(TP+FP), measures the accuracy of positive predictions, while recall measures the completeness of positive predictions. The Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) summarizes the entire PR curve into a single value, with higher values indicating better performance [15].

Unlike AUROC, AUPRC is highly sensitive to class imbalance. As the proportion of positive instances decreases, the baseline AUPRC (what a random classifier would achieve) also decreases, making high AUPRC scores more difficult to achieve in imbalanced scenarios. This sensitivity can be both an advantage and limitation: while it makes AUPRC more informative about performance on the minority class in imbalanced settings, it also makes comparisons across datasets with different class distributions challenging. Research has shown that class imbalance cannot be easily disentangled from classifier performance when measured via AUPRC, complicating direct interpretation of this metric across different experimental conditions [17].

Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC)

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), also known as the phi coefficient, is a balanced measure of classification quality that accounts for all four confusion matrix categories (TP, FP, TN, FN). The MCC formula for binary classification is: MCC = (TP×TN - FP×FN) / √((TP+FP)(TP+FN)(TN+FP)(TN+FN)). The coefficient yields a value between -1 and +1, where +1 represents a perfect prediction, 0 indicates no better than random prediction, and -1 signifies total disagreement between prediction and observation [18].

MCC is widely recognized as a reliable metric that provides balanced measurements even in the presence of class imbalance, as it considers the balance ratios of all four confusion matrix categories [18]. With the increasing prevalence of multiclass classification problems in ADMET research involving three or more classes (e.g., multiple levels of toxicity or different CYP enzyme inhibition strengths), macro-averaged and micro-averaged extensions of MCC have been developed. Recent statistical research has formalized the framework for MCC in multiclass settings and introduced methods for constructing asymptotic confidence intervals for these extended metrics, enhancing their utility for rigorous statistical comparison [18].

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Classification Metrics

| Metric | Calculation Basis | Range | Optimal Value | Random Classifier | Sensitivity to Class Imbalance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUROC | TPR vs. FPR across thresholds | 0 to 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Low [17] |

| AUPRC | Precision vs. Recall across thresholds | 0 to 1 | 1 | Proportion of positives | High [17] |

| MCC | All four confusion matrix categories | -1 to +1 | +1 | 0 | Low [18] |

Table 2: Metric Performance in Different ADMET Scenarios

| Research Context | Recommended Metric(s) | Reported Performance | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid Toxicity Prediction [15] | AUROC, AUPRC, MCC | AUROC=0.824, AUPRC=0.851, MCC=0.51 | Comprehensive assessment for highly imbalanced data (229 active vs. 1257 inactive compounds) |

| SGLT2 Inhibition Classification [16] | AUROC, AUPRC, MCC | AUROC=0.909-0.926, AUPRC=0.858-0.864 | Multiple random seeds (13,17,23,29,31) show consistent performance across metrics |

| General ADMET Benchmarking [11] | AUROC, AUPRC, MCC | Varies by endpoint | Standardized evaluation using multiple metrics for robust comparison |

The choice between these metrics depends significantly on the specific requirements of the ADMET classification task and the characteristics of the dataset. AUROC provides a comprehensive view of model performance across all thresholds and remains stable across datasets with different class distributions, making it ideal for initial model comparison and selection. However, in highly imbalanced scenarios where the primary interest lies in the minority class (e.g., rare toxic compounds), AUPRC offers a more informative assessment of performance on the positive class, despite its sensitivity to the class ratio [17].

MCC serves as an excellent single-value metric that balances all aspects of the confusion matrix, particularly valuable when both false positives and false negatives carry significant consequences. In drug discovery contexts, where the costs of missing a toxic compound (false negative) and incorrectly flagging a safe compound as toxic (false positive) must be balanced, MCC provides a realistic assessment of practical utility. The recent development of statistical inference methods for MCC in multiclass problems further enhances its applicability to complex ADMET classification tasks beyond simple binary classification [18].

Experimental Protocols and Applications in ADMET Research

Implementation in Toxicity Prediction Studies

In a study focusing on thyroid-disrupting chemicals targeting thyroid peroxidase, researchers implemented a stacking ensemble framework integrating deep neural networks with strategic data sampling to address challenges posed by imbalanced and limited data. The experimental protocol involved curated data from the U.S. EPA ToxCast program, comprising 1,519 chemicals initially, which was preprocessed to 1,486 compounds (229 active, 1,257 inactive) after removing entries with invalid SMILES notations, inorganic compounds, mixtures, and duplicates [15].

The methodology employed a rigorous evaluation approach where models were assessed using AUROC, AUPRC, and MCC to provide a comprehensive performance picture. The research demonstrated that their active stacking-deep learning approach achieved an MCC of 0.51, AUROC of 0.824, and AUPRC of 0.851. Notably, the study highlighted that while a full-data stacking ensemble trained with strategic sampling performed slightly better in MCC, their method achieved marginally higher AUROC and AUPRC while requiring up to 73.3% less labeled data. This comprehensive metric evaluation provided strong evidence for the efficiency and effectiveness of their proposed framework [15].

Protocol for Multi-Seed Model Validation

A detailed code audit of an automated drug discovery framework targeting Alzheimer's disease revealed a robust experimental protocol for metric evaluation across multiple random seeds. The implementation computed AUROC, AUPRC, F1, MCC, balanced accuracy, and Brier score to ensure comprehensive assessment [16].

The key methodological steps included:

Multiple Random Seeds: Five distinct seeds (13, 17, 23, 29, 31) were explicitly defined and used consistently across all experiments to ensure reproducibility and account for variability.

Natural Performance Variation: The protocol embraced natural variance across seeds rather than reporting only optimal results, with documented performance ranges such as AUROC=0.909-0.926 and AUPRC=0.858-0.864 for SGLT2 inhibition classification.

Threshold Optimization: Classification thresholds were optimized on validation sets rather than using default values, ensuring practical applicability.

Authentic Metric Computation: All metrics were computed from actual model predictions without hardcoded results or manipulation, as verified through code audit [16].

This multi-faceted evaluation approach exemplifies current best practices in ADMET classification research, where comprehensive metric assessment across multiple experimental conditions provides more reliable and translatable results for drug discovery applications.

Visualization of Metric Relationships and Workflows

Diagram 1: Relationship between classification metrics and their properties in ADMET contexts. This workflow illustrates how different metrics derive from model predictions and their respective strengths for handling class imbalance, a common challenge in toxicity prediction.

Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Classification

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ADMET Classification Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Application in Metric Computation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | ECFP, Avalon, ErG, 12 distinct structural fingerprints [15] [11] | Feature representation for classification models | Capture predefined substructures, topology-derived substructures, electrotopological state indices, and atom pair relationships |

| Benchmark Platforms | TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons), ChEMBL, ADMEOOD, DrugOOD [11] | Standardized datasets for fair metric comparison | Curated ADMET endpoints with scaffold, temporal, and out-of-distribution splits |

| Machine Learning Libraries | XGBoost, Scikit-learn, RDKit [16] [14] | Implementation of classifiers and metric calculations | Classical algorithms (random forests, SVMs) with built-in metric functions |

| Graph Neural Networks | GCN, GAT, MPNN, AttentiveFP [19] [11] | Advanced architecture for molecular classification | Learned embeddings directly from molecular graphs; GAT shows best OOD generalization |

| Automated Pipeline Tools | Auto-ADMET, CaliciBoost [11] | Optimized metric performance through pipeline tuning | Dynamic feature selection, algorithm choice, and hyperparameter optimization |

Based on current research and benchmarking practices in ADMET prediction, the following recommendations emerge for metric selection in classification tasks:

Employ Multiple Metrics: Relying on a single metric provides an incomplete picture of model performance. The ADMET Benchmark Group and recent research consistently advocate for using AUROC, AUPRC, and MCC in conjunction to gain complementary insights [16] [11].

Context-Dependent Interpretation: Consider the specific requirements of your classification task when prioritizing metrics. For overall performance assessment and cross-study comparison, AUROC's invariance to class imbalance makes it particularly valuable. For focus on minority class performance (e.g., rare toxic compounds), AUPRC provides crucial insights despite its sensitivity to class distribution. For a balanced single-value metric that considers all confusion matrix categories, MCC offers reliable assessment [18] [17].

Account for Data Characteristics: Dataset size, class distribution, and expected application context should guide metric emphasis. In highly imbalanced scenarios common to toxicity prediction (e.g., 1:6 active-to-inactive ratios), MCC and AUPRC provide valuable perspectives on minority class performance, while AUROC enables comparison across differently balanced datasets [15] [17].

Implement Rigorous Validation: Follow established experimental protocols including multiple random seeds, appropriate data splits (scaffold, temporal, or out-of-distribution), and statistical significance testing, particularly for MCC differences in paired study designs [16] [18].

The ongoing evolution of ADMET prediction research, with emerging approaches like graph neural networks, multimodal learning, and foundation models, continues to underscore the importance of comprehensive, multi-metric evaluation strategies. By applying these metrics appropriately within well-designed experimental frameworks, researchers can more reliably advance computational models for drug discovery and toxicity assessment.

In the field of drug discovery, the accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties is crucial for reducing late-stage failures and bringing viable drugs to market. Machine learning (ML) models have emerged as transformative tools for these predictions, offering rapid and cost-effective alternatives to traditional experimental approaches [9]. However, the reliability of these models hinges on the use of robust evaluation metrics to assess their predictive performance. For regression tasks—which predict continuous values like solubility or permeability—metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Coefficient of Determination (R²), and Spearman's Correlation provide distinct, critical insights into model accuracy, error distribution, and ranking ability. This guide objectively compares these essential metrics within the context of ADMET regression models, supported by experimental data and protocols from contemporary research.

Core Metric Definitions and Comparative Analysis

Regression metrics quantify the differences between a model's predicted values and the actual experimental values. Each metric offers a unique perspective on model performance.

- MAE (Mean Absolute Error): Represents the average magnitude of absolute differences between predicted and actual values, providing a direct measure of average error. It is less sensitive to large outliers.

- RMSE (Root Mean Square Error): The square root of the average of squared differences. It penalizes larger errors more heavily than MAE, making it useful for highlighting significant prediction failures.

- R² (Coefficient of Determination): Indicates the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. It measures how well unseen samples are likely to be predicted by the model.

- Spearman's Correlation: A non-parametric measure of rank correlation that assesses how well the relationship between predicted and actual values can be described using a monotonic function, crucial for evaluating a model's ranking capability.

The table below summarizes the characteristics and ideal values for these metrics in an ADMET modeling context.

Table 1: Core Regression Metrics for ADMET Model Evaluation

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Best Value | Key Consideration in ADMET | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | ( \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} | yi - \hat{y}i | ) | Average error magnitude | 0 | Easy to interpret; does not weight outliers. |

| RMSE | ( \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \hat{y}_i)^2} ) | Average error, penalizing large deviations | 0 | Sensitive to outliers; useful for identifying large errors. | ||

| R² | ( 1 - \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \hat{y}i)^2}{\sum{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \bar{y})^2} ) | Proportion of variance explained | 1 | Context-dependent; a value of 1 indicates perfect prediction. | ||

| Spearman's Correlation | ( 1 - \frac{6 \sum d_i^2}{n(n^2 - 1)} ) (for ranks) | Strength of monotonic relationship | 1 (or -1) | Assesses ranking ability, vital for compound prioritization. |

Experimental Performance Benchmarking in ADMET Research

Recent benchmarking studies provide concrete data on the performance of various ML models, evaluated using these metrics, on specific ADMET properties.

In a study focused on predicting Caco-2 permeability—a key indicator of intestinal absorption—researchers conducted a comprehensive validation of multiple machine learning algorithms. The models were trained on a large, curated dataset of 5,654 compounds and evaluated on an independent test set. The results demonstrated that the XGBoost algorithm generally provided superior predictions compared to other models [20].

Another critical study benchmarked ML models for predicting seasonal Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) and reported exemplary performance for a Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model. The table below shows its quantitative performance, which serves as a high benchmark for model accuracy in regression tasks [21].

Table 2: Exemplary Model Performance from a Recent Benchmarking Study [21]

| Model | RMSE | MAE | R² |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | 0.0030 | 0.0022 | 0.9999 |

| Efficient Linear Regression (ELR) | Higher by 189.1% | Higher by 190.09% | Lower by 20.56% |

| Regression Trees (RT) | Higher by 124.05% | Higher by 111.1% | Lower by 0.2604% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for ADMET Model Validation

To ensure the reliability and generalizability of ADMET prediction models, researchers follow rigorous experimental protocols. A typical workflow for building and evaluating a regression model, as applied in recent Caco-2 permeability studies, involves several key stages [20].

Key Stages in the Experimental Workflow

Data Collection and Curation: Models are trained on large, curated datasets assembled from public sources like ChEMBL and proprietary in-house data. For instance, the creation of the PharmaBench dataset used a multi-agent LLM system to consistently process 14,401 bioassays, resulting in a high-quality benchmark of over 52,000 entries for 11 key ADMET properties [22]. Data cleaning includes molecular standardization, removal of inorganic salts and organometallics, extraction of parent organic compounds from salts, and de-duplication to ensure consistent and accurate labels [4].

Data Splitting: The curated dataset is typically split into training, validation, and test sets. To ensure a rigorous evaluation of generalizability, a scaffold split is often used, where compounds are divided based on their molecular backbone, ensuring that structurally dissimilar molecules are in the training and test sets. This prevents the model from simply "memorizing" structures and tests its ability to generalize to novel chemotypes [20] [4].

Feature Engineering and Model Training: Molecules are converted into numerical representations (features) such as molecular descriptors or fingerprints. Feature selection methods (filter, wrapper, or embedded) are then used to identify the most relevant features, which improves model performance and interpretability [9]. Multiple algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, and Deep Learning models) are trained and their hyperparameters are tuned, often using cross-validation on the training set [20] [4].

Model Evaluation and Validation: The final model is evaluated on the held-out test set using the suite of regression metrics. Beyond this, robust validation includes:

- External Validation: Testing the model on a completely separate, often proprietary, dataset to assess its real-world applicability. For example, a model trained on public data was validated on Shanghai Qilu’s in-house dataset of 67 compounds [20].

- Statistical Testing: Integrating cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing to compare models reliably, confirming that performance improvements are statistically significant and not due to random chance [4].

- Applicability Domain Analysis: Defining the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable, which is critical for guiding its proper use in prospective drug discovery [20].

Building and validating robust ADMET models requires a suite of software tools, databases, and computational resources. The table below details key components of the modern computational scientist's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ADMET Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ADMET Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | Generates essential numerical representations (features) from molecular structures for model training [20] [4]. |

| PharmaBench | Public Benchmark Dataset | Provides curated experimental data for ADMET properties. | Serves as an open-source dataset for training and benchmarking model performance on pharmaceutically relevant properties [22]. |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Public Benchmark Platform | Aggregates curated datasets for drug discovery. | Provides a leaderboard and standardized benchmarks for comparing model performance across various ADMET tasks [4]. |

| Scikit-learn | ML Library | Implements machine learning algorithms and evaluation metrics. | Provides tools for model building (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) and for calculating metrics like MAE, RMSE, and R² [22]. |

| ChemProp | Deep Learning Framework | Implements Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs). | Used for building graph-based models that directly learn from molecular structures, often achieving state-of-the-art accuracy [20] [4]. |

| GPT-4 / LLMs | Large Language Model | Extracts information from unstructured text. | Used in advanced data mining to curate larger datasets by identifying and standardizing experimental conditions from scientific literature [22]. |

The rigorous evaluation of regression models using MAE, RMSE, R², and Spearman's correlation is fundamental to advancing ADMET prediction research. As evidenced by recent benchmarking studies, no single metric provides a complete picture; instead, they offer complementary views on a model's accuracy, error profile, and ranking capability. The ongoing evolution of this field is driven by the development of larger, more clinically relevant datasets like PharmaBench, the implementation of more rigorous validation protocols such as scaffold splitting and statistical testing, and the adoption of sophisticated ML algorithms. By systematically applying and interpreting these essential metrics, drug development researchers can better discriminate between high-performing and mediocre models, thereby making more reliable decisions in the costly and high-stakes process of bringing new therapeutics to patients.

In the field of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction, the accuracy and generalizability of machine learning models are paramount. The process of splitting datasets into training, validation, and test sets is not a mere procedural step but a critical determinant of a model's real-world utility. This guide objectively compares the three predominant partitioning strategies—scaffold, temporal, and out-of-distribution (cluster-based) splits—within the context of rigorous evaluation metrics for ADMET classification and regression models.

In drug discovery, a high-quality drug candidate must demonstrate not only efficacy but also appropriate ADMET properties at a therapeutic dose [23]. The development of in silico models to predict these properties has thus become a cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical research [24]. However, the performance of these models is often over-optimistic when evaluated using simple random splits of available data. This is because random splits can lead to data leakage, where structurally or temporally very similar compounds appear in both training and test sets, giving a false impression of high accuracy.

The broader thesis in model evaluation is that a split must simulate the genuine predictive challenge a model will face. This involves forecasting properties for novel chemical scaffolds, for compounds that will be synthesized in the future, or for those that lie outside the model's known chemical space. Consequently, scaffold, temporal, and out-of-distribution (cluster) splits have emerged as the gold-standard strategies for rigorous benchmarking, as they prevent data leakage and provide a more realistic assessment of model performance [25].

Comparative Analysis of Partitioning Strategies

The core of rigorous ADMET evaluation lies in choosing a data split that aligns with the ultimate goal: deploying models to guide the design of new chemical entities. The following table provides a structured comparison of the three key strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Dataset Splitting Strategies for ADMET Modeling

| Splitting Strategy | Core Principle | Best-Suited For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Split | Partitioning compounds based on their Bemis-Murcko scaffolds, ensuring that molecules with different core structures are separated [25]. | Evaluating a model's ability to generalize to entirely novel chemotypes or scaffold hops [24] [25]. | Maximizes structural diversity between train and test sets; prevents over-optimism from evaluating on structurally analogous compounds. | May be overly pessimistic for projects focused on analog series; can be challenging if the entire dataset has limited scaffold diversity. |

| Temporal Split | Partitioning compounds based on the chronology of experiment dates or their addition to a database [25]. | Simulating real-world prospective prediction and validating a model's performance on future compounds, as done in industrial workflows [25]. | Provides the most realistic validation for industrial settings; reflects the evolving nature of chemical space over time. | Requires timestamp metadata; can be influenced by shifts in corporate screening strategies over time. |

| Out-of-Distribution (Cluster Split) | Grouping compounds via clustering techniques on molecular fingerprints (e.g., PCA-reduced Morgan fingerprints) and splitting clusters [25]. | Assessing model performance on chemically distinct regions of space not covered in the training data. | Maximizes dissimilarity between training and test sets; ensures a robust assessment on novel chemical domains. | The specific clustering algorithm and parameters can influence the final split and model performance. |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

The theoretical strengths of these splitting strategies are validated through specific experimental protocols and benchmarks in the literature. The consistent finding is that more rigorous splits lead to a more accurate, and often lower, estimate of a model's true performance.

Implementation in Standardized Benchmarks

The Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) has formulated a widely adopted ADMET Benchmark Group comprising 22 datasets. For every dataset in this benchmark, the standard protocol is to use the scaffold split to partition the data into training, validation, and test sets, with a holdout of 20% of samples for the final test [24]. This approach ensures that models are evaluated on their ability to predict properties for molecules with core structures they have never seen during training. Performance is then measured using task-appropriate metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) or Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) for classification, with AUPRC preferred for imbalanced data [24].

Evidence from Multitask Learning

The impact of splitting is further magnified in multitask ADMET models, where multiple property endpoints for a set of small molecules are modeled simultaneously. To prevent cross-task leakage, multitask splits maintain aligned train, validation, and test partitions for all endpoints, ensuring that each compound's data are split consistently across every task being predicted [25].

Studies on such multitask datasets reveal that temporal splits yield more realistic and less optimistic generalization estimates compared to random or per-task splits [25]. Furthermore, the benefit of multitask learning—where information from related tasks improves model generalization—is highly dependent on the splitting method. The gains are most pronounced and reliably measured when using these rigorous strategies, as they prevent leakage and accurately reflect the challenge of predicting for novel compounds [25].

Case Study: Caco-2 Permeability Modeling

A recent study on predicting Caco-2 permeability, a key property for oral drug absorption, underscores the importance of rigorous evaluation. The research involved curating a large dataset of 5,654 non-redundant Caco-2 permeability records. The standard protocol for model development and evaluation involved randomly dividing these records into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, followed by a crucial step: a performance assessment on an additional external validation set of 67 compounds from an industrial in-house collection [20].

This two-tiered validation approach tests the model's performance not only on a random holdout from the same data source but, more importantly, its transferability to real-world industrial data, which may have a different distribution. The study found that while models like XGBoost performed well on the internal test set, their performance on the external set is the true test of utility, mirroring the principles of temporal and out-of-distribution splits [20].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Key ADMET Endpoints Under Rigorous Splits

| ADMET Endpoint | Task Type | Dataset Size | Primary Metric | Typical Split Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | Regression | 5,654 - 7,861 compounds [20] | RMSE, R² | Random (80-10-10) with External Validation [20] |

| hERG Inhibition | Binary Classification | 806 compounds [26] | Accuracy, AUROC | Temporal/Holdout [26] |

| AMES Mutagenicity | Binary Classification | 8,348 compounds [23] | Accuracy (0.843) [23] | Scaffold [24] |

| CYP2D6 Inhibition | Binary Classification | 13,130 compounds [24] | AUPRC | Scaffold [24] |

| VDss | Regression | 1,130 compounds [24] | Spearman | Scaffold [24] |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate dataset splitting strategy in ADMET research.

Diagram 1: Strategy Selection Workflow

Successful implementation of rigorous dataset splits requires access to standardized datasets, software tools, and computational resources. The following table details key solutions for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ADMET Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Splitting Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Benchmark Dataset | Provides a curated ADMET Benchmark Group with 22 datasets [24]. | Supplies pre-defined, aligned scaffold splits for rigorous and standardized benchmarking [24] [25]. |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Provides fundamental cheminformatics functionality for handling molecular data. | Used to calculate molecular descriptors, generate Morgan fingerprints for clustering, and perform Bemis-Murcko scaffold analysis for scaffold splits [20]. |

| admetSAR | Web Server / Predictive Tool | Predicts 18+ ADMET properties using pre-trained models [23]. | Provides a benchmark for model performance and exemplifies the endpoints (e.g., hERG, Caco-2) for which robust splits are critical. Its ADMET-score offers a composite drug-likeness metric [23]. |

| Scikit-learn | Python Library | Offers a wide array of machine learning algorithms and utilities. | Contains implementations for clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means) for out-of-distribution splits and for model training/validation. |

| XGBoost / Random Forest | Machine Learning Algorithm | Powerful, tree-based ensemble methods for classification and regression. | Frequently used as top-performing baselines in ADMET prediction challenges, as validated under rigorous scaffold and temporal splits [20] [25]. |

The application of machine learning (ML) to predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties has become fundamental to modern drug discovery. These computational approaches provide a fast and cost-effective means for researchers to prioritize compounds with optimal pharmacokinetics and minimal toxicity early in development [22]. However, the progression of the field depends on the availability of standardized, high-quality benchmark resources that enable fair comparison of algorithms and realistic assessment of their utility in real-world drug discovery scenarios [27] [28]. Three significant resources have emerged to address this need: Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC), MoleculeNet, and PharmaBench.

Each platform addresses distinct challenges in molecular machine learning. MoleculeNet established one of the first large-scale benchmark collections to address the lack of standard evaluation platforms [27]. TDC provides a unifying framework that spans the entire therapeutics pipeline with specialized benchmark groups [29] [30]. Most recently, PharmaBench leverages large language models to create expansive, experimentally-conscious datasets [22] [31]. This guide provides a detailed technical comparison of these resources, enabling researchers to select appropriate benchmarks for their specific ADMET modeling requirements.

Comprehensive Platform Profiles

Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC)

Therapeutics Data Commons is an open-science platform that provides AI/ML-ready datasets and learning tasks spanning the entire drug discovery and development process [30]. TDC structures its resources into specialized benchmark groups, with the ADMET group being particularly prominent for small molecule property prediction [29]. The platform emphasizes rigorous evaluation protocols, requiring multiple independent runs with different random seeds to calculate robust performance statistics (mean and standard deviation) and employing scaffold splitting that groups compounds by their core molecular structure to simulate real-world generalization to novel chemotypes [29].

TDC provides a programmatic framework for model evaluation. Researchers can utilize benchmark group utilities to access standardized data splits and evaluation metrics, as shown in this typical workflow for the ADMET group:

This structured approach ensures consistent evaluation across different models and research groups. TDC also maintains leaderboards that track model performance on various benchmarks, promoting competition and transparency in the field [29].

MoleculeNet

MoleculeNet represents one of the pioneering efforts to create a standardized benchmark for molecular machine learning, introduced as part of the DeepChem library [27]. Its comprehensive collection encompasses over 700,000 compounds across diverse property categories, including quantum mechanics, physical chemistry, biophysics, and physiology [27]. This broad coverage enables researchers to evaluate model performance across different molecular complexity levels, from electronic properties to human physiological effects.

The benchmark provides high-quality implementations of multiple molecular featurization methods and learning algorithms, significantly lowering the barrier to entry for molecular ML research [27]. MoleculeNet introduced dataset-specific recommended splits and metrics, acknowledging that different molecular tasks require different evaluation strategies. For instance, random splits may be appropriate for quantum mechanical properties, while scaffold splits are more relevant for biological activity prediction [27].

A key contribution of MoleculeNet is its systematic comparison of featurization and algorithm combinations across diverse datasets, demonstrating that learnable representations generally offer the best performance but struggle with data-scarce scenarios and highly imbalanced classification [27]. The benchmark also highlighted that for certain tasks like quantum mechanical and biophysical predictions, physics-aware featurizations can outweigh the choice of learning algorithm [27].

PharmaBench

PharmaBench is the most recent addition to ADMET benchmarks, distinguished by its innovative use of large language models (LLMs) for data curation and its focus on addressing limitations in existing benchmarks [22]. The platform was created to overcome two critical issues in previous resources: (1) the limited utilization of publicly available bioassay data, and (2) the poor representation of compounds relevant to industrial drug discovery pipelines [22].

PharmaBench employs a sophisticated multi-agent LLM system to extract experimental conditions from unstructured assay descriptions in public databases like ChEMBL [22]. This system consists of three specialized agents:

- Keyword Extraction Agent (KEA): Identifies and summarizes key experimental conditions for different ADMET experiment types

- Example Forming Agent (EFA): Generates few-shot learning examples based on KEA output

- Data Mining Agent (DMA): Extracts experimental conditions from all assay descriptions using the generated examples [22]

This innovative approach enabled the curation of 156,618 raw entries from 14,401 bioassays, resulting in a refined benchmark of 52,482 entries across eleven key ADMET properties [22] [31]. The resulting dataset better represents the molecular weight range typical of drug discovery projects (300-800 Dalton) compared to earlier benchmarks like ESOL (mean 203.9 Dalton) [22].

Comparative Analysis of Dataset Coverage and Characteristics

Table 1: Coverage of Key ADMET Properties Across Benchmark Platforms

| ADMET Property | TDC | MoleculeNet | PharmaBench |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | |||

| Caco-2 Permeability | ✓ | ||

| HIA | ✓ | ||

| Distribution | |||

| BBB Penetration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PPB | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Metabolism | |||

| CYP450 Inhibition | ✓ (Multiple isoforms) | ✓ (2C9, 2D6, 3A4) | |

| Excretion | |||

| Clearance (HLMC/RLMC/MLMC) | ✓ | ||

| Toxicity | |||

| Ames Mutagenicity | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Physicochemical | |||

| Lipophilicity (LogD) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Water Solubility | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Total ADMET Datasets | 22 in ADMET group [32] | Includes ADMET among other categories [27] | 11 specifically focused on ADMET [31] |

Table 2: Dataset Characteristics and Scale

| Characteristic | TDC | MoleculeNet | PharmaBench |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Compounds | Not specified (28 ADMET datasets with >100K entries [22]) | >700,000 (across all categories) [27] | 52,482 (after processing) [31] |

| Data Curation Approach | Manual curation and integration of existing datasets [22] | Curation and integration of public databases [27] | Multi-agent LLM system extracting experimental conditions [22] |

| Key Innovations | Benchmark groups, standardized evaluation protocols [29] | Diverse molecular properties, recommended splits/metrics [27] | Experimental condition awareness, drug-like compound focus [22] |

| Primary Use Case | End-to-end therapeutic pipeline evaluation [30] | Broad molecular machine learning benchmarking [27] | ADMET prediction with experimental context [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Protocols

Robust evaluation methodologies are critical for meaningful comparison of ADMET models. TDC has established particularly comprehensive guidelines, requiring models to be evaluated across multiple runs with different random seeds (minimum of five) to ensure statistical reliability of reported performance [29]. The platform employs scaffold splitting as the default approach for most ADMET tasks, which groups molecules based on their Bemis-Murcko scaffolds and ensures that training and test sets contain structurally distinct compounds [29]. This strategy better simulates real-world drug discovery scenarios where models must predict properties for novel chemotypes.

MoleculeNet introduced the concept of dataset-specific recommended splits and metrics, recognizing that different molecular tasks require appropriate evaluation strategies [27]. For example, random splitting may be suitable for quantum mechanical properties where compounds are diverse and independent, while scaffold splitting is more appropriate for biological activity prediction where generalization to novel structural classes is essential.

Critical Considerations for Real-World Utility

Recent research has highlighted important limitations in standard benchmark practices. Inductive.bio emphasizes that conventional scaffold splits may still allow highly similar molecules across training and test sets, potentially overestimating real-world performance [28]. They recommend more stringent similarity-based splitting using molecular fingerprints (e.g., Tanimoto similarity of ECFP4) to exclude training compounds with high similarity (≥0.5) to test compounds [28].

Another critical insight is the importance of assay-stratified evaluation. When benchmark data is pooled from multiple sources (assays), a phenomenon known as Simpson's Paradox can occur where models appear to perform well on aggregated data but show near-zero predictive power within individual assays [28]. This is particularly relevant for drug discovery where models must prioritize compounds within specific chemical series rather than across global chemical space.

Correlation metrics like Spearman rank correlation may be more informative than absolute error metrics for lead optimization contexts, as they better capture a model's ability to correctly rank compounds by property values—often the primary use case in medicinal chemistry decisions [28].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Comparative Model Performance on TDC

Table 3: Example Performance Metrics on TDC ADMET Benchmark Group [32]

| Task | Metric | Top Performing Method | XGBoost Performance | XGBoost Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco2 Permeability | MAE | RDKit2D | Competitive | Top 3 |

| HIA Absorption | AUC | AttentiveFP | 1st | 1st |

| BBB Penetration | AUC | Multiple | Competitive | Top 3 |

| PPB Distribution | MAE | XGBoost | 1st | 1st |

| CYP Metabolism | AUC | XGBoost | 1st (multiple isoforms) | 1st |

| AMES Toxicity | AUC | XGBoost | 1st | 1st |

| Solubility | MAE | XGBoost | 1st | 1st |

| Lipophilicity | MAE | XGBoost | 1st | 1st |

| Overall ADMET Group | Multiple | - | 1st in 18/22 tasks | Top 3 in 21/22 tasks |

Recent research demonstrates how these benchmarks enable direct algorithm comparison. A study evaluating XGBoost with ensemble features on the TDC ADMET benchmark group achieved top-ranked performance in 18 of 22 tasks and top-3 ranking in 21 tasks [32]. The implementation used six featurization methods (MACCS, ECFP, Mol2Vec, PubChem, Mordred, and RDKit descriptors) with hyperparameter optimization across multiple random seeds following TDC guidelines [32].

Impact of Dataset Quality on Model Performance

PharmaBench's development process highlighted how dataset characteristics directly impact model utility. The authors noted that traditional benchmarks like ESOL contain compounds with significantly lower molecular weight (mean 203.9 Dalton) than typical drug discovery compounds (300-800 Dalton), potentially limiting their relevance for practical applications [22]. By extracting experimental conditions from assay descriptions, PharmaBench enables more controlled dataset construction that controls for confounding variables like buffer composition, pH, and experimental methodology [22].

The platform also addresses the critical issue of experimental variability, where the same compound may show different property values under different experimental conditions [22]. By explicitly capturing these conditions through LLM-powered extraction, PharmaBench facilitates the creation of more consistent and reliable benchmarks for ADMET prediction.

Implementation Workflows

To illustrate the typical experimental workflow for benchmark evaluation, the following diagram outlines the generalized process for assessing models on ADMET benchmarks:

Generalized Workflow for ADMET Benchmark Evaluation

The multi-agent LLM system implemented in PharmaBench represents a significantly more sophisticated data curation approach, as detailed in the following workflow:

PharmaBench Multi-Agent LLM Curation Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for ADMET Benchmark Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function in Research | Platform Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Featurization | ECFP Fingerprints, MACCS Keys, RDKit Descriptors, Mordred Descriptors | Convert molecular structures to machine-readable features | All platforms [32] |

| Deep Learning Architectures | AttentiveFP, Graph Neural Networks, Graph Convolutional Networks | Learn directly from molecular structures or features | TDC, MoleculeNet [32] |

| Traditional ML Models | XGBoost, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines | Baseline and competitive performance | All platforms [32] |

| Evaluation Metrics | MAE, RMSE, AUC, Spearman Correlation | Quantify model performance for regression and classification | All platforms [29] [27] [28] |

| Splitting Strategies | Random Split, Scaffold Split, Stratified Split | Create training/validation/test sets | All platforms [29] [27] |

| LLM-Powered Curation | GPT-4 based Multi-Agent System | Extract experimental conditions from text | PharmaBench [22] |

The evolution of public benchmark resources for ADMET prediction has significantly advanced the field of molecular machine learning. TDC, MoleculeNet, and PharmaBench each offer distinct advantages: MoleculeNet provides broad coverage across molecular property types, TDC offers specialized therapeutic benchmarking with rigorous evaluation protocols, and PharmaBench introduces innovative LLM-powered curation with enhanced experimental condition awareness.

Future developments in ADMET benchmarking will likely focus on several critical areas: (1) improved representation of drug discovery compounds and properties, (2) more realistic evaluation methodologies that better predict real-world utility, and (3) increased integration of experimental context to account for protocol variability. As these benchmarks continue to mature, they will play an increasingly vital role in translating machine learning advancements into practical drug discovery applications, ultimately accelerating the development of safe and effective therapeutics.

Researchers should select benchmarks based on their specific needs—TDC for comprehensive therapeutic pipeline evaluation, MoleculeNet for broad molecular property prediction comparison, and PharmaBench for ADMET-specific modeling with experimental condition considerations. As the field progresses, the integration of insights from all these resources will provide the most robust foundation for advancing ADMET prediction capabilities.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Robust Evaluation Frameworks and Selecting Models

The accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a pivotal challenge in modern drug discovery, where inappropriate metric selection can lead to misleading model evaluations and costly late-stage failures. The pharmaceutical industry faces staggering attrition rates, with over 90% of candidates failing in clinical trials, many due to inadequate ADMET properties [6]. The evolution of artificial intelligence and machine learning has introduced transformative capabilities for early-stage screening, yet the effectiveness of these models depends critically on aligning evaluation metrics with the specific biological and regulatory contexts of each ADMET endpoint [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for matching validation metrics to specific ADMET endpoints, from intestinal permeability (Caco-2) to cardiac safety (hERG), enabling researchers to make informed decisions in model development and compound optimization.

ADMET Endpoint Classification and Metric Selection Framework

ADMET properties encompass diverse biological phenomena measured through various experimental assays, necessitating a stratified approach to metric selection based on endpoint characteristics. Fundamentally, these endpoints divide into classification tasks (e.g., binary outcomes like hERG inhibition) and regression tasks (e.g., continuous values like Caco-2 permeability). Within this framework, additional considerations include the clinical consequence of prediction errors, regulatory implications, and the inherent noise characteristics of the underlying experimental data [4] [9]. For instance, toxicity endpoints like hERG inhibition demand high-sensitivity metrics due to the severe clinical consequences of false negatives, while metabolic stability predictions may prioritize correlation-based metrics for rank-ordering compounds.

The following table summarizes recommended metrics for key ADMET endpoints based on recent benchmarking studies and industrial applications:

Table 1: Recommended Metrics for Key ADMET Endpoints

| ADMET Endpoint | Endpoint Type | Primary Metrics | Secondary Metrics | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | Regression | MAE, R² | RMSE, Spearman | High accuracy needed for BCS classification [33] |

| hERG Inhibition | Classification | AUROC, AUPRC | Sensitivity, Specificity | High sensitivity critical for cardiac safety [13] |

| Bioavailability | Classification | AUROC | Precision, Recall | Class imbalance common [13] |

| Lipophilicity (LogP) | Regression | MAE | R² | Key for multiparameter optimization [13] |

| Aqueous Solubility | Regression | MAE | RMSE | Log-transformed values typically used [4] |