Validating Real-World Evidence for Health Technology Assessment: A Framework for Robust Decision-Making in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Real-World Evidence (RWE) for Health Technology Assessment (HTA).

Validating Real-World Evidence for Health Technology Assessment: A Framework for Robust Decision-Making in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Real-World Evidence (RWE) for Health Technology Assessment (HTA). It explores the foundational role of RWE from Real-World Data (RWD) in bridging evidence gaps between clinical trials and real-world clinical practice. The content details advanced methodological frameworks, including causal inference and the target trial approach, endorsed by regulatory and HTA bodies like the FDA and NICE. It addresses critical challenges in data quality and governance and offers optimization strategies. Through a comparative analysis of regulatory and HTA use cases, the article establishes validation criteria to ensure RWE is fit-for-purpose, supporting robust and timely healthcare decision-making for pricing, reimbursement, and patient access.

The Rising Imperative of Real-World Evidence in Modern Healthcare Assessment

The paradigm of evidence generation for healthcare decision-making is undergoing a fundamental shift. While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard for establishing efficacy under controlled conditions, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) bodies are increasingly recognizing their limitations in reflecting real-world clinical practice [1]. This gap has catalyzed the strategic adoption of real-world data (RWD) and real-world evidence (RWE) to strengthen the assessment of medical technologies across their lifecycle.

The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 in the United States was a pivotal moment, designed to accelerate medical product development and bring innovations to patients more efficiently [2]. In response, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) created a framework for evaluating RWE to support regulatory decisions, signaling a formal recognition of its value [2]. This movement is equally strong in Europe, with initiatives like the European Data Analysis and Real-World Interrogation Network (DARWIN EU) expected to conduct hundreds of RWE studies annually to support regulatory decision-making [1].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the precise distinction between RWD and RWE—and how they are operationalized within HTA—is no longer academic; it is a practical necessity for navigating modern evidence requirements and demonstrating the value of new therapies in diverse patient populations.

Defining the Terms: The Fundamental Distinction Between RWD and RWE

A clear conceptual and practical separation between Real-World Data and Real-World Evidence is the foundation for their correct application in HTA research.

Real-World Data (RWD) are the raw, unprocessed data relating to patient health status and/or the delivery of health care routinely collected from a variety of sources [2] [3]. Think of RWD as the foundational building blocks or the "raw material" for generating evidence [4]. These data are captured during routine clinical care and daily life, not within the strict protocols of a traditional clinical trial.

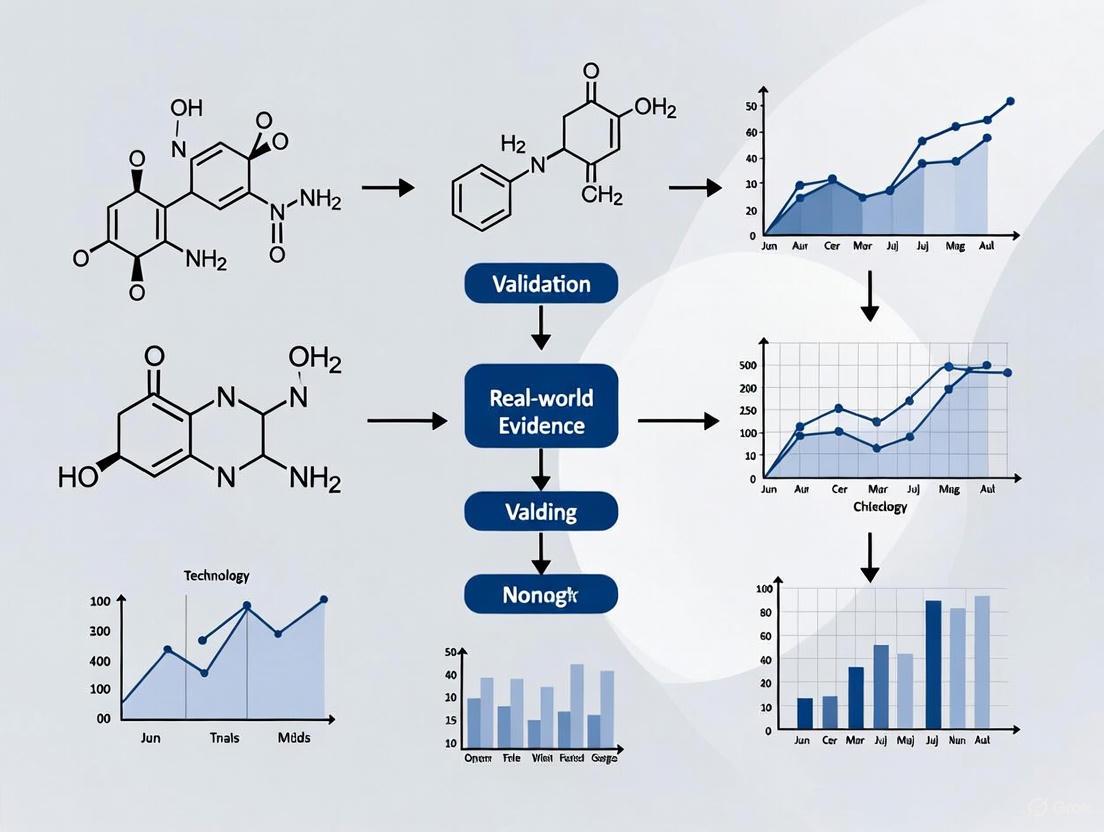

Real-World Evidence (RWE), in contrast, is the clinical evidence derived from the analysis and interpretation of RWD [2] [3]. It is the "knowledge gained from analyzing and interpreting RWD" [5]. RWE provides insights into the usage, potential benefits, and risks of a medical product in real-world clinical settings [2] [6]. The following diagram illustrates this transformative relationship and the process of generating RWE.

RWD is a diverse ecosystem of data types, each offering unique insights into the patient journey. The table below catalogs the primary sources of RWD relevant to HTA research.

Table: Primary Sources and Applications of Real-World Data in HTA

| Data Source | Description | Key Applications in HTA & Research |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Records (EHRs) | Digital records of patient health information, including medical history, diagnoses, treatments, and lab results [4] [7]. | Provides rich clinical detail on disease progression, treatment patterns, and outcomes in routine practice [5] [7]. |

| Claims & Billing Data | Administrative data generated from healthcare claims for reimbursement [4] [6]. | Ideal for understanding healthcare resource utilization, costs, and treatment patterns at a population level [7]. |

| Disease & Product Registries | Organized systems that collect uniform data on a specific disease, condition, or exposure to a product [2] [4]. | Provides longitudinal data on natural history of disease, treatment outcomes, and safety in specific patient populations [6] [5]. |

| Patient-Generated Data | Data collected directly from patients, including patient-reported outcomes (PROs), wearable device data, and mobile app data [5] [7]. | Offers insight into patient-experienced symptoms, quality of life, and daily health metrics outside clinical settings [6]. |

| Pharmacy Data | Information on prescribed and dispensed medications [4] [7]. | Sheds light on medication adherence, persistence, and therapy sequences in real-world populations [4]. |

The Critical Role of RWD and RWE in Health Technology Assessment

HTA agencies are tasked with determining the value of new health technologies, a process that extends beyond regulatory approval for market entry to include pricing, reimbursement, and guidance on use within healthcare systems. RWD and RWE are becoming indispensable in this process by addressing key evidence gaps left by traditional RCTs.

How RWE Complements RCT Evidence

RCTs are designed for high internal validity but can suffer from limited generalizability due to strict eligibility criteria, homogeneous patient populations, and short follow-up periods [1] [5]. RWE addresses these limitations by:

- Providing Long-Term Outcomes Data: RWE can monitor the safety and durability of treatment response over a much longer timeframe than typical RCTs [8].

- Assessing Effectiveness in Heterogeneous Populations: RWE includes outcomes from older patients, those with comorbidities, and other groups often excluded from RCTs, providing a more representative picture of effectiveness in clinical practice [7].

- Informing Decisions in Rare Diseases and Oncology: For rare diseases or novel oncology treatments where large RCTs are unfeasible or unethical, RWE from external control arms (ECAs) can provide crucial contextual evidence for treatment effects [9] [8].

Key Applications of RWE in the HTA Lifecycle

The use of RWE in HTA is not monolithic; it serves distinct purposes throughout the technology lifecycle. A study analyzing European HTA bodies found that RWE is used for various endpoints, with varying levels of acceptance across different agencies [9].

Table: RWE Acceptance for Different Purposes in HTA (Adapted from PMC [9])

| Purpose of RWE in HTA | Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Efficacy Claims | Using RWE (e.g., from an External Control Arm) to substantiate the effectiveness of a treatment, often for single-arm trials [9]. | Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) in lymphoma was assessed using an ECA comparing it to historical standard of care [9]. |

| Informing Disease Background | Using RWE to characterize the natural history of a disease, burden of illness, or epidemiology [9]. | Establishing the incidence and prevalence of a rare disease to demonstrate unmet need and contextualize the value of a new therapy. |

| Post-Marketing Surveillance | Monitoring the safety of a product after it has entered the market [2] [6]. | Using EHR or claims data to identify potential adverse events not detected in pre-market clinical trials. |

| Supporting Reassessments | Using RWE in HTA reassessments to refine coverage, pricing, and reimbursement decisions after initial market entry [8]. | The UK's Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) uses RWE to collect additional evidence on drugs granted provisional access [8]. |

Methodological Protocols: Generating Regulatory and HTA-Grade RWE

Transforming RWD into RWE that is fit-for-purpose and deemed reliable by HTA bodies and regulators requires rigorous methodology. The following section outlines key experimental and study design protocols.

The RWE Generation Workflow: From Data to Evidence

The process of generating RWE is iterative and requires careful planning and execution at every stage to ensure the evidence produced is valid and reliable. The following diagram details this multi-stage workflow.

1. Define Research Question & Protocol: The foundation of any robust RWE study is a pre-specified research question and analysis plan [1]. This includes defining the patient population, interventions, comparators, and outcomes, and outlining the statistical methods to address potential confounding.

2. Data Sourcing & Collection: This involves identifying and accessing RWD from one or more of the sources listed in Section 2.1. A critical consideration is whether the data are fit-for-purpose—that is, relevant, valid, and reliable for the specific research question [1] [7].

3. Data Curation & Harmonization: Raw RWD is often unstructured, inconsistent, and stored across disparate systems. This stage involves significant data engineering to clean, standardize, and transform the data into a structured format suitable for analysis [5]. This may include processing unstructured physician notes from EHRs or linking datasets (e.g., linking EHR data with claims data) to create a more complete picture of the patient journey [7].

4. Study Design & Analysis: This is the core of transforming RWD into RWE. Key methodological approaches include:

- Non-Interventional Studies: Observational studies that analyze RWD without intervening in patient care. These require advanced statistical methods like propensity score matching to control for confounding and emulate a randomized study as closely as possible [9] [3].

- External Control Arms (ECAs): Using existing RWD to create a control group for a single-arm trial. This is particularly valuable in oncology and rare diseases [9]. For example, the therapy avelumab (Bavencio) for Merkel Cell Carcinoma was assessed using an ECA derived from a retrospective observational study [9].

- Pragmatic Clinical Trials: Trials that are interventional in nature but are designed to closely reflect real-world clinical practice and often leverage RWD collection infrastructure [1].

5. Evidence Interpretation & Submission: The final analyzed evidence must be interpreted in the context of its limitations, such as residual confounding or potential data quality issues, and transparently reported for submission to HTA bodies and regulators [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for RWE Generation

Table: Essential Reagents and Solutions for RWE Generation

| Component / Solution | Function in RWE Generation |

|---|---|

| Data Governance Framework | A set of international standards and policies to ensure the ethical and acceptable use of RWD, covering data privacy, security, and patient consent [1]. |

| Data Curation & Linkage Tools | Software and algorithms used to clean, standardize, and harmonize disparate RWD sources, and to link patient records across datasets while maintaining privacy [5] [7]. |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | Software (e.g., R, Python with pandas) containing libraries for advanced statistical methods like propensity score matching, inverse probability weighting, and multivariate regression to address confounding [5]. |

| Sentinel Initiative / DARWIN EU | Large-scale, regulatory-grade data networks that provide curated and validated RWD for safety monitoring and study execution [1] [5]. |

| ML395 | ML395, MF:C26H29N5O2, MW:443.5 g/mol |

| m-PEG8-thiol | m-PEG8-thiol, CAS:651042-83-0, MF:C17H36O8S, MW:400.5 g/mol |

Comparative Analysis: RWE Acceptance Across HTA Bodies

The acceptance and use of RWE in HTA decision-making are not uniform. A comparative analysis reveals significant differences in receptivity and focus across major HTA agencies.

Table: Comparative Use and Acceptance of RWE in Select HTA Bodies (Synthesized from [9] [8])

| HTA Body / Country | Receptivity to RWE | Primary Focus & Common Use of RWE |

|---|---|---|

| NICE (UK) | More receptive [9]. | Cost-effectiveness and clinical outcomes; uses RWE within frameworks like the Cancer Drugs Fund for managed access and reassessment [8]. |

| AEMPS (Spain) | More receptive [9]. | Budgetary impact and epidemiological analysis [9]. |

| AIFA (Italy) | Intermediate. | Primarily focused on budgetary impact analysis [9]. |

| HAS (France) | Less accepting [9]. | Prioritizes clinical relevance; uses RWE in specific post-registration studies and temporary use programs [8]. |

| G-BA (Germany) | Less accepting [9]. | Focuses on clinical benefit; reassessment of products (often limited to orphan drugs) can incorporate RWE [8]. |

A study examining ten technologies found that the level of scrutiny from HTA bodies is "considerably higher" when RWE is used to substantiate efficacy claims compared to when it is used for other purposes, such as describing disease background [9]. The key criteria driving acceptance across all markets are the representativeness of the data source, overall transparency in the study, and robust methodologies [9].

The distinction between Real-World Data as the raw material and Real-World Evidence as the derived, actionable insights is more than semantic—it is a fundamental concept that shapes how robust, credible evidence is generated for HTA. The landscape is evolving rapidly: the proportion of HTA reports incorporating RWE rose from 6% in 2011 to 39% in 2021 [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, success in this new paradigm requires a commitment to methodological rigor, transparency, and early engagement with HTA bodies. By strategically employing RWD and RWE to answer questions that RCTs cannot, the industry can provide the comprehensive evidence needed to demonstrate the true value of new therapies in real-world practice, ultimately leading to more efficient and informed healthcare decision-making for all patients.

The evaluation of new medical treatments has long been dominated by the randomized controlled trial (RCT), widely considered the gold standard for establishing therapeutic efficacy due to its rigorous design that minimizes bias through randomization and strict protocol adherence [10]. However, a significant challenge has emerged in what researchers term the efficacy-effectiveness gap—the disconnect between the significant results seen in highly controlled RCTs and the inconsistent outcomes observed when treatments are applied in routine clinical practice [10]. This gap exists because RCTs often exclude patients with comorbidities, complex medications, or socioeconomic factors that represent a substantial proportion of those treated in real-world settings [10].

Real-world evidence (RWE), derived from the analysis of real-world data (RWD) collected outside the constraints of traditional clinical trials, offers a complementary perspective that addresses these limitations [11]. RWD sources include electronic health records (EHRs), insurance claims data, patient registries, and data from wearable devices and mobile health platforms [10] [12]. Regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) are increasingly accepting RWE to support regulatory decisions, with studies showing that between 1998 and 2019, 17 FDA or EMA new drug applications used RWD in oncology and metabolism, all receiving approval [11].

The following diagram illustrates how RCTs and RWE function as complementary, rather than competing, sources of evidence throughout the therapeutic development lifecycle:

Comparative Analysis: RCTs vs. RWE Across Critical Dimensions

The fundamental differences between RCTs and RWE stem from their distinct purposes, methodologies, and applications. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their key characteristics:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of RCTs and RWE Across Critical Dimensions

| Dimension | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Real-World Evidence (RWE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Establish efficacy under ideal, controlled conditions [10] | Evaluate effectiveness in routine clinical practice [10] |

| Study Design | Experimental, with random allocation to intervention and control groups [10] | Observational, analyzing data from actual clinical practice [12] |

| Population Characteristics | Homogeneous populations with strict inclusion/exclusion criteria; often excludes elderly, those with comorbidities, or complex medications [10] [13] | Heterogeneous populations reflecting diversity seen in clinical practice, including typically excluded groups [10] [12] |

| Data Collection Methods | Prospective collection using standardized protocols and predetermined endpoints [10] | Collection from routine care sources: EHRs, claims data, registries, patient-reported outcomes [10] [14] |

| Key Strengths | High internal validity, controls confounding through randomization, establishes causal relationships [10] | High external validity, captures long-term outcomes and safety signals, represents diverse populations [10] [12] |

| Key Limitations | Limited generalizability, high cost and time requirements, may miss rare adverse events [10] | Potential for confounding and bias, variable data quality, methodological challenges [10] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Foundation for initial approval by FDA and EMA [10] | Increasingly accepted for post-market studies, label expansions, and in rare diseases [9] [11] |

| Ideal Applications | Pivotal trials for regulatory approval, establishing proof of concept [10] | Post-market surveillance, comparative effectiveness research, outcomes in rare diseases [9] [11] |

Methodological Protocols: Generating Valid Real-World Evidence

Data Source Selection and Validation

The foundation of robust RWE generation lies in the selection and validation of appropriate real-world data sources. Common sources include electronic health records (EHRs), which provide clinical data from routine care; claims databases, containing billing information that reveals treatment patterns and healthcare utilization; patient registries, which systematically collect data on specific populations or conditions; and emerging data sources such as wearable devices and mobile health applications that capture patient-generated health data [10] [14] [12].

To ensure data quality, researchers must implement rigorous validation protocols. These include cross-validation against other data sources where possible, completeness checks for critical variables, plausibility testing to identify outliers or inconsistent entries, and temporal validation to ensure proper sequencing of events [14]. For example, in a study using EHR data to examine treatment patterns for chronic pain, researchers would verify that pain scores are recorded at appropriate intervals and that medication prescriptions align with diagnosed conditions [10].

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Overcoming the inherent limitations of observational data requires sophisticated methodological approaches. Propensity score matching (PSM) is frequently employed to minimize selection bias by creating comparable treatment and control groups based on observed characteristics [10]. This statistical technique calculates the probability (propensity) that a patient would receive a specific treatment based on their baseline characteristics, then matches patients across treatment groups with similar propensities, effectively mimicking randomization for observed covariates [10].

Target trial emulation represents a more advanced framework for designing observational studies that closely mirror the structure of RCTs [11]. This approach involves explicitly defining key trial components—including eligibility criteria, treatment strategies, outcomes, and follow-up periods—before analyzing observational data, thereby reducing methodological biases [11]. For instance, when using RWD to create an external control arm (ECA) for a single-arm trial in oncology, researchers would apply the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as the clinical trial to the real-world population, ensure comparable outcome measurements, and align the analysis timeframes [9].

Additional techniques include instrumental variable analysis to address unmeasured confounding, difference-in-differences approaches to account for secular trends, and Bayesian methods that incorporate prior knowledge to strengthen inferences from observational data [11]. The UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has demonstrated the acceptability of these approaches, as exemplified by their recommendation of mobocertinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer based on a single-arm trial that used RWD as an external comparator [11].

Practical Applications: Case Studies Demonstrating RWE's Value

Addressing Evidence Gaps in Rare Diseases and Oncology

RWE has proven particularly valuable in therapeutic areas where traditional RCTs face practical or ethical challenges. In rare diseases, patient populations are often too small to conduct adequately powered RCTs. Similarly, in oncology, the rapid evolution of treatment standards and the heterogeneity of cancer types complicate the design and interpretation of RCTs [9] [11].

Several compelling case examples illustrate this application:

Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah): For relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, this CAR-T cell therapy utilized an external control arm constructed from multiple data sources (SCHOLAR-1, ZUMA-1, CORAL, Eyre, and PIX301) to demonstrate comparative effectiveness when a randomized design was not feasible [9].

Avelumab (Bavencio): For Merkel cell carcinoma, researchers developed an ECA from a retrospective observational study (100070-Obs001) designed to evaluate outcomes under current clinical practices, including both first-line and second-line patients from the US and Europe [9].

Blinatumomab (Blincyto): For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, an ECA compared blinatumomab with continued chemotherapy using data from a retrospective study (study20120148) [9].

These examples demonstrate how RWE can provide contextualization for single-arm trials, offering insights into how experimental therapies perform compared to existing standards of care when randomized head-to-head comparisons are unavailable.

Post-Marketing Surveillance and Safety Monitoring

Even after rigorous RCTs lead to regulatory approval, important safety questions often remain due to the limited sample sizes and relatively short duration of most clinical trials. RWE plays a critical role in post-marketing surveillance by detecting rare adverse events and evaluating long-term safety profiles in broader patient populations [14] [12].

A prominent example comes from COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring. While phase III trials for vaccines included tens of thousands of participants, they were still insufficiently powered to detect very rare events. RWE analysis discovered rare cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia following ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination, with incidence rates ranging from 1 per 26,000 to 1 per 127,000—far too rare to detect in clinical trials of 21,635 participants [14]. This RWE directly informed changes to vaccine administration guidelines in the UK as early as April 2021 [14].

Informing Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Reassessment

Health technology assessment bodies worldwide are increasingly incorporating RWE into their decision-making processes. A targeted review of 40 HTAs across six agencies (including NICE, HAS, and CADTH) found that 55% used RWE, particularly for orphan therapies [15]. These reassessments employed RWE primarily to address uncertainties related to primary and secondary endpoints, long-term outcomes, and treatment utilization patterns [15].

The acceptance of RWE varies across HTA bodies, with UK and Spanish agencies being more receptive, while French and German agencies are more cautious [9]. The key criteria driving RWE acceptance across markets include representativeness of the data source, overall transparency in the study, and robust methodologies [9].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Components for RWE Generation

Generating valid RWE requires both methodological expertise and appropriate technological resources. The table below outlines essential components of the modern RWE research toolkit:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Real-World Evidence Generation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Infrastructure | Secure Data Environments (SDEs) [14] | Provide secure, governed access to sensitive patient data while maintaining privacy and compliance with regulations |

| Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model [14] | Standardizes data structure and terminology across different sources to enable systematic analysis | |

| Methodological Approaches | Propensity Score Matching (PSM) [10] | Balances observed covariates between treatment groups to reduce selection bias in observational comparisons |

| Target Trial Emulation [11] | Provides a structured framework for designing observational studies that mimic the key features of RCTs | |

| Analytical Technologies | Bayesian Statistical Methods [11] | Incorporates prior knowledge and continuously updates probability estimates as new data becomes available |

| Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning [12] | Identifies complex patterns in large, heterogeneous datasets and helps address confounding | |

| Data Linkage Tools | Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage (PPRL) [14] | Enables connection of patient records across different data sources while protecting personal information |

| Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) [12] | Facilitates efficient data extraction and integration from diverse healthcare systems and platforms | |

| N-(Azido-PEG3)-N-bis(PEG3-acid) | N-(Azido-PEG3)-N-bis(PEG3-acid), CAS:2055042-57-2, MF:C26H50N4O13, MW:626.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PDE8B-IN-1 | PDE8B-IN-1, MF:C14H18N8OS, MW:346.41 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence landscape in healthcare is evolving from a rigid hierarchy with RCTs at the apex to a complementary ecosystem where RCTs and RWE each contribute their unique strengths. RCTs remain indispensable for establishing causal efficacy under controlled conditions, while RWE provides crucial insights into clinical effectiveness in diverse real-world populations [10] [12]. This synergistic relationship enables more comprehensive evidence generation throughout the therapeutic lifecycle—from early development through post-market surveillance.

The successful integration of these approaches requires ongoing methodological innovation, cross-stakeholder collaboration, and the development of standardized best practices. Regulatory and HTA bodies are increasingly formalizing their frameworks for RWE evaluation, as exemplified by NICE's RWE Framework and the EMA's DARWIN EU initiative [14] [1]. As these frameworks mature and methodological rigor advances, the strategic combination of RCTs and RWE will ultimately accelerate the development of effective treatments and improve patient outcomes through evidence-based medicine that reflects both scientific rigor and clinical reality.

The integration of real-world evidence (RWE) into regulatory and health technology assessment (HTA) decision-making represents one of the most significant advancements in healthcare policy and drug development. As innovative therapies, particularly in oncology, rare diseases, and advanced therapeutic medicinal products (ATMPs), emerge at an unprecedented rate, regulatory bodies and HTA agencies worldwide are developing structured frameworks to incorporate data beyond traditional randomized controlled trials. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have each launched strategic initiatives to formalize the generation and assessment of RWE, aiming to accelerate patient access to safe, effective, and cost-effective treatments.

This comparative guide examines the current operational frameworks, methodological requirements, and strategic priorities of these three major agencies regarding RWE validation and use. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative landscape of evidence requirements is crucial for designing efficient development programs that satisfy both regulatory and reimbursement evidentiary standards. The drive toward RWE represents a fundamental shift from a siloed approach to an integrated evidence generation paradigm that spans the entire product lifecycle from pre-market approval to post-market surveillance and value assessment.

Agency Comparison: Strategic Frameworks and Operational Priorities

Table: Comparative Overview of Key RWE Initiatives at FDA, EMA, and NICE

| Agency/Aspect | FDA (United States) | EMA (European Union) | NICE (United Kingdom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strategic Focus | Building RWE infrastructure and addressing clinical trial transparency [16] | Implementing EU HTA Regulation with joint clinical assessments [17] [18] | Evolving HTA methods for challenging therapies and leveraging AI [19] |

| Key RWE Initiative | Real-World Evidence Framework; Clinical trial transparency enforcement [16] | Joint Clinical Assessment (JCA) for medicines & medical devices [17] [20] | 2025 RWE Framework update; HTA Innovation Lab [21] [19] |

| Current Implementation Status | Ongoing framework development with recent enforcement pushes [16] | Mandatory for oncology/ATMPs (2025); orphan medicines (2028); all medicines (2030) [18] | Modular updates to HTA manual; severity modifier implementation [19] [22] |

| Patient Engagement Focus | Patient Experience Data (PED) guidance in development [23] | Structured patient input in JCA and Joint Scientific Consultation [18] | Patient input in severity assessment; ILAP patient engagement [22] |

| Technology Scope | Pharmaceuticals, biologics, medical devices, digital health technologies [16] | Pharmaceuticals, ATMPs, and high-risk medical devices (Class IIb/III) [20] | Pharmaceuticals, medical technologies, digital health, diagnostics [19] |

Table: RWE Assessment Methodologies and Acceptance Criteria

| Methodological Aspect | FDA Approach | EMA/EU HTA Network Approach | NICE Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design Acceptance | Emphasis on real-world data quality and fit-for-purpose study designs [24] | Joint Clinical Assessments focus on comparative clinical effectiveness [18] | Accepts RWE alongside RCT data; target trial emulations encouraged [21] [19] |

| Data Quality Standards | Assessing reliability and relevance of real-world data sources [24] | Harmonized evidence requirements across member states [17] | 2025 RWE Framework strengthens validation and reporting standards [21] |

| Evidence Gaps Addressed | Framework to address uncertainties in effectiveness [24] | Addresses fragmentation in European HTA processes [18] | Managed Access Agreements for evidence generation [22] |

| External Control Arms | Accepts under specific conditions with rigorous validation [24] | Considered within JCA for rare diseases and oncology [18] | Accepted, particularly for ultra-rare diseases with natural history data [21] |

FDA: RWE Framework and Regulatory Modernization

Strategic Priority Structure

The FDA's Human Foods Program recently underwent a significant reorganization, centralizing risk management activities into three key areas, though its principal RWE initiatives reside within its drug and device centers [25]. The agency's RWE Framework, coupled with its focus on clinical trial transparency, represents a comprehensive approach to evidence generation. In October 2025, the FDA emphasized closing the "clinical trial reporting gap" through enhanced enforcement of reporting requirements on ClinicalTrials.gov, highlighting transparency as an ethical obligation for human subjects research [16].

RWE Program Implementation

The FDA is actively expanding its information-gathering efforts for AI-enabled medical devices, including a scheduled November 2025 meeting of its Digital Health Advisory Committee to discuss benefits, risks, and risk mitigation measures for generative AI-enabled digital mental health devices [16]. The agency has also published a Request for Public Comment on approaches to measuring and evaluating the performance of AI-enabled medical devices in real-world settings, indicating a growing focus on real-world performance assessment of digital health technologies [16].

EMA: EU HTA Regulation Implementation

Joint Clinical Assessment Framework

The implementation of the EU Health Technology Assessment Regulation (HTAR) on January 12, 2025, marks a transformative shift in how medicines are evaluated across the European Union [18]. The regulation establishes a framework for Joint Clinical Assessments (JCAs) that will provide a harmonized clinical evaluation available to all member states. The rollout is phased, beginning in 2025 with new oncology medicines and advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), expanding to orphan medicinal products in 2028, and encompassing all new medicines authorized by the EMA by 2030 [18].

Operational Infrastructure

The technical implementation of the HTAR is being facilitated through a centralized HTA secretariat and close cooperation with the EMA [17]. The EMA provides the HTA secretariat with business pipeline information on planning and forecasting for joint clinical assessments and joint scientific consultations for both medicines and medical devices [17]. For medical devices, which will come into scope in 2026, the implementing act on Joint Scientific Consultation (JSC) outlines procedures for parallel consultations that coordinate with existing expert panel consultations, creating a streamlined pathway for high-risk devices [20].

Diagram: EU HTA Regulation Process Flow and Implementation Timeline

NICE: Methodological Evolution and Access Pathways

HTA Methodological Innovations

NICE's 2025 updates reflect a sophisticated evolution in HTA methodology designed to address challenging therapeutic areas while maintaining rigorous health economic standards. The severity modifier, introduced in 2022 and reviewed in 2024, operates by calculating both absolute and proportional quality-adjusted life year (QALY) shortfalls, allowing for a higher cost-effectiveness threshold for treatments addressing more severe conditions [22]. The implementation has resulted in a higher proportion of positive recommendations (84.4%) compared with the previous end-of-life modifier (82.7%), demonstrating its practical impact on access decisions [22].

Specialized Appraisal Pathways

For ultra-rare diseases, NICE has refined its highly specialized technologies (HST) criteria effective April 2025, providing clearer definitions for ultra-rare prevalence (1:50,000 or less in England), disease burden, and eligibility thresholds (no more than 300 people in England) [22]. The Innovative Licensing and Access Pathway (ILAP) was relaunched in January 2025 with more selective entry criteria and a streamlined service offering a single point of contact from pre-pivotal trial to routine reimbursement [22]. For technologies with evidence uncertainties, Managed Access Agreements (MAAs) enable temporary funding while additional data is collected, typically lasting up to five years [22].

Experimental Protocols for RWE Generation

RWE Study Validation Protocol

Table: Essential Reagents and Solutions for RWE Study Implementation

| Research Component | Function/Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Data | Source for patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes | Data mapping to common data model; validation of key clinical fields [21] |

| Validated Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Instruments | Capture patient-experienced symptoms and functional impacts | Alignment with FDA/EMA PRO guidance; linguistic validation for multinational studies [23] |

| Common Data Model (e.g., OMOP) | Standardize data structure across disparate sources | Implementation of ETL processes; quality checks for vocabulary mapping [24] |

| Propensity Score Methods | Balance measured covariates between treatment groups | Selection of appropriate variables; assessment of balance achieved [24] |

| Sensitivity Analysis Framework | Assess robustness to unmeasured confounding | Implementation of quantitative bias analysis; E-value calculations [24] |

Decentralized Clinical Trial (DCT) Implementation

Recent methodological advances have positioned decentralized clinical trials as a valuable approach for generating RWE, particularly for rare diseases where traditional trials face recruitment challenges. The protocol incorporates electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePROs), telemedicine platforms, and home health nursing to collect clinical trial data in real-world settings [21]. Implementation requires meticulous planning of digital infrastructure, validation of remote measurement systems, and compliance with regional regulatory requirements for decentralized trial elements [21].

The regulatory and HTA landscape is undergoing rapid transformation, with the FDA, EMA, and NICE each developing distinctive yet increasingly aligned approaches to real-world evidence incorporation. The FDA emphasizes evidence generation infrastructure and transparency enforcement, the EMA is focused on harmonizing assessment methodologies across member states through the HTA Regulation, while NICE continues to refine its value assessment framework with specialized pathways for challenging therapeutic areas. For drug development professionals, success in this evolving environment requires early strategic planning, engagement with regulatory and HTA bodies throughout the development process, and robust evidence generation strategies that address both regulatory requirements and health technology assessment needs. The convergence of these initiatives signals a broader industry transition toward integrated evidence generation capable of demonstrating both clinical and economic value across the product lifecycle.

The landscape of evidence generation for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) is undergoing a fundamental transformation. While Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard for establishing efficacy under controlled conditions, they often leave critical evidence gaps regarding performance in routine clinical practice [26]. Real-World Evidence (RWE), derived from data collected outside traditional clinical trials, is increasingly bridging these gaps by providing insights into treatment effectiveness, long-term safety, and patient outcomes in diverse, real-world populations [27]. This shift is driven by the need to understand the true value of health technologies in the context of daily clinical care, where patient heterogeneity, co-morbidities, and variable treatment patterns are the norm [28]. The growing prevalence of RWE in HTA submissions marks a pivotal evolution in how stakeholders—including regulators, payers, and providers—evaluate new medical interventions, moving from a pure efficacy focus to a more comprehensive assessment of effectiveness and value in real-world settings [21].

Quantitative Analysis of RWE Adoption in HTA

Global HTA Body Acceptance and Guidelines

The integration of RWE into HTA processes is progressing at varying speeds across different jurisdictions. A 2022 survey of Roche subsidiaries across seven countries provides a quantitative snapshot of the methodological guidance and acceptance landscape at that time [26].

Table 1: Status of RWE Methodological Guidelines in HTA Bodies (as of June 2022)

| Country | HTA Body | RWE Methodological Guidelines Published? |

|---|---|---|

| France | HAS | Yes |

| Germany | IQWiG/G-BA | Yes |

| United Kingdom | NICE | Yes |

| Brazil | Conitec | No |

| Canada | CADTH/INESSS | No |

| Italy | AIFA | No |

| Spain | MSSSI/AEMPS | No |

The data reveals that by mid-2022, less than half of the major HTA bodies surveyed had published formal methodological guidelines for RWE, indicating a developing but not yet mature regulatory landscape [26]. However, this picture is evolving rapidly. By 2025, additional agencies including NICE have refined their RWE frameworks, with NICE's 2025 update specifically marking "a shift toward treating RWE as a strategic, rather than supplementary, evidence source" [21].

RWE Utilization in European HTA Submissions

The implementation of the European Union's Joint Clinical Assessment (JCA) in January 2025 represents a significant milestone for standardized evidence assessment across member states [29]. While the full impact is still emerging, early data demonstrates concrete integration of RWE into these processes.

Table 2: Early JCA Volumes and RWE Context (2025 Data)

| Therapeutic Category | Projected JCAs (2025) | Actual JCAs (Early 2025) | RWE Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology Medicines | 17 | 9 | RWE used to support value in reimbursement cases |

| Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) | 8 | 1 (plus 1 oncology ATMP) | Critical for evidence in rare diseases |

The slightly lower-than-expected volume of early JCA submissions (9 for oncology versus 17 projected) suggests manufacturers may be adopting a cautious approach, potentially learning from initial assessments before submitting their own dossiers [21]. Within these submissions, RWE has played a substantively important role. Analysis of European pricing and reimbursement cases between 2014 and 2025 demonstrated that RWE played a key role in securing full reimbursement in 7 out of 16 European cases for orphan medicines and provided supporting input in conditional agreements for the remaining cases [21].

Methodological Frameworks for RWE Generation

Real-World Evidence (RWE) is the clinical evidence regarding the usage and potential benefits or risks of a medical product derived from the analysis of Real-World Data (RWD) [2]. RWD encompasses data relating to patient health status and/or healthcare delivery routinely collected from diverse sources [27]. These data sources can be categorized into three main groups based on their inherent quality and collection methodology [30]:

- Studies and Registries: Highest quality data collected purposefully for analysis using scientific methods and defined protocols (e.g., disease registries, prospective observational studies).

- Clinical Records: Data originating from routine medical care without study protocols but under healthcare professional supervision (e.g., Electronic Health Records (EHRs), claims and billing data).

- Unsupervised Sources: Data collected without professional supervision or protocol (e.g., patient-generated data from mobile apps, wearables, patient forums).

Each category requires different methodological approaches to address challenges related to data quality, completeness, and potential biases [30].

Experimental Protocols for RWE Generation

Protocol for Retrospective Database Studies

Objective: To generate comparative effectiveness evidence using existing healthcare databases (e.g., EHR, claims data) to inform HTA submissions.

Methodology:

- Data Source Selection: Identify fit-for-purpose databases with sufficient population size, relevant variables, and longitudinal follow-up. Common sources include EHR systems like Flatiron Health (specializing in oncology) and claims databases like Optum [31] [27].

- Cohort Definition: Apply explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria to define patient cohorts. The study population should align with the HTA population of interest (PICO framework) [26].

- Outcome Measurement: Identify and validate outcome measures within the database. For example, overall survival or progression-free survival in oncology studies often requires curation from unstructured EHR data [31].

- Confounder Adjustment: Implement advanced statistical methods to address confounding by indication, including:

- Propensity Score Matching: Create balanced treatment groups based on observed baseline characteristics [26].

- Multivariable Regression: Adjust for multiple confounders simultaneously in outcome models [30].

- Instrumental Variable Analysis: Address unmeasured confounding when suitable instruments are available [30].

Validation: Perform sensitivity analyses to test robustness of findings to different methodological assumptions [30].

Protocol for Prospective RWE Generation

Objective: To collect targeted RWD prospectively to address specific evidence gaps in HTA submissions.

Methodology:

- Registry Design: Establish a disease or product registry with a predefined protocol, data collection forms, and statistical analysis plan. For example, the European Cystic Fibrosis Society Registry collects demographic and clinical data to monitor treatment patterns and outcomes [27].

- Site Selection: Recruit diverse clinical sites to ensure population representativeness, including academic centers, community hospitals, and private practices [21].

- Data Collection: Implement standardized data collection procedures, often using electronic data capture systems. Define core data elements relevant to HTA needs (e.g., patient characteristics, treatment patterns, clinical outcomes, healthcare resource utilization, patient-reported outcomes) [27].

- Quality Assurance: Establish data quality checks, source data verification procedures, and audit trails to ensure data reliability [31].

Analysis: Pre-specified statistical analyses comparing outcomes across treatment groups with appropriate adjustment for confounding factors.

Diagram: RWE Generation Workflow for HTA. This diagram illustrates the sequential process for generating RWE, from defining the research question through to HTA submission, highlighting key methodological stages.

Comparative Analysis: RWE vs. RCT Evidence

The complementary strengths and limitations of RWE and RCT evidence make them suitable for answering different types of research questions in HTA.

Table 3: Comparison of RCT and RWE Characteristics [28] [27]

| Characteristic | Randomized Controlled Trials | Real-World Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Efficacy | Effectiveness |

| Setting | Experimental, controlled | Real-world clinical practice |

| Patient Selection | Strict inclusion/exclusion criteria | Heterogeneous, representative populations |

| Intervention | Fixed, per protocol | Variable, at physician's discretion |

| Comparator | Placebo or selective active control | Multiple alternative interventions as used in practice |

| Follow-up | Fixed duration, per protocol | Variable, as per routine care |

| Sample Size | Limited by design and cost | Potentially very large |

| Key Strength | High internal validity, controls confounding | High external validity, generalizability |

| Primary Limitation | Limited generalizability to broader populations | Potential for unmeasured confounding |

RCTs remain preferred for establishing causal efficacy under ideal conditions, while RWE provides crucial insights into clinical effectiveness in routine practice [28]. For HTA bodies, this distinction is critical—while regulators focus primarily on benefit-risk balance, HTA agencies assess comparative benefit versus existing options, making RWE particularly valuable for understanding a technology's performance in relevant healthcare systems and patient populations [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RWE Generation

The successful generation of RWE for HTA requires specialized "research reagents"—tools and platforms that enable robust data collection, management, and analysis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RWE Generation

| Solution Category | Representative Platforms | Primary Function in RWE Generation |

|---|---|---|

| EHR-Based Analytics | Flatiron Health, IQVIA EMR | Structure and analyze unstructured electronic health record data, particularly valuable for oncology |

| Claims Data Analytics | Optum, IQVIA Claims | Analyze healthcare utilization, treatment patterns, and costs from administrative billing data |

| Data Linkage Platforms | TriNetX, Aetion | Link and harmonize data from multiple sources (EHR, claims, registries) for comprehensive analysis |

| Analytical & Validation Tools | IBM Watson Health, Aetion | Apply advanced analytics and methodological validation to address confounding and bias in RWD |

| Regulatory Science Platforms | FDA Sentinel Initiative | Provide regulatory-grade RWE infrastructure for safety monitoring and effectiveness research |

These platforms address critical methodological challenges in RWE generation, including data interoperability, confounder control, and analytic transparency [31]. For instance, Flatiron Health's platform structures unstructured EHR data from a network of oncology clinics, enabling research on real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in diverse patient populations [31]. Similarly, the FDA's Sentinel Initiative provides a distributed data system that enables active monitoring of medical product safety using routinely collected healthcare data [27].

Country-Specific Variations in RWE Acceptance

The acceptance and use of RWE in HTA processes vary significantly across countries, reflecting different evidentiary standards, healthcare systems, and policy priorities.

- United Kingdom: NICE has emerged as a progressive adopter of RWE, with its 2025 framework update strengthening methodological standards. NICE tends to accept external comparators and natural history data, particularly for rare diseases [21].

- Germany: The G-BA/IQWiG system maintains stricter requirements, limiting RWE use mainly to ultra-rare diseases where RCTs are not feasible. They require rigorous data collection systems and often commission their own observational studies [21].

- France: HAS uses RWE extensively for re-evaluating technologies already reimbursed based on RCT evidence, and has published comprehensive guidelines on RWE use in HTA [26] [21].

- Italy: AIFA frequently employs RWE to inform outcome-based agreements, linking reimbursement to real-world performance metrics [21].

- United States: The FDA has developed a comprehensive framework for evaluating RWE to support regulatory decisions, including drug approvals and post-market studies [2].

These variations present challenges for global evidence generation strategies, requiring tailored approaches for different HTA bodies [26]. However, the implementation of the EU JCA may drive greater harmonization in RWE standards across European markets over time [21].

The quantification of RWE's growing prevalence in HTA submissions reveals a fundamental shift in evidence generation paradigms. From supporting 7 out of 16 European orphan drug reimbursement cases to being integrated into the newly launched EU Joint Clinical Assessment process, RWE has transitioned from a supplementary source to a strategic asset in health technology assessment [21]. The ongoing development of methodological guidelines by HTA bodies, advances in analytical techniques, and the emergence of specialized technology platforms all point toward continued growth in RWE's role and importance.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering RWE generation is no longer optional but essential for successful HTA submissions and market access. Future success will depend on understanding country-specific requirements, implementing methodologically robust study designs, and leveraging appropriate technology platforms to generate regulatory-grade real-world evidence that addresses the evolving needs of health technology assessment bodies worldwide.

Frameworks and Methods for Generating Regulatory-Grade RWE

In health technology assessment (HTA) and drug development, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) represent the gold standard for establishing causal effects of interventions. However, RCTs are often impractical, unethical, untimely, or unable to address the sheer volume of causal questions in real-world settings [32]. Real-world evidence (RWE) derived from observational data—such as electronic health records, insurance claims databases, and medical registries—has emerged as a critical alternative [33] [34]. The fundamental challenge lies in ensuring that analyses of this observational data yield valid, actionable causal estimates rather than biased associations.

The target trial framework provides a systematic methodology to overcome this challenge. This approach involves two critical steps: first, specifying the protocol of a hypothetical randomized trial (the "target trial") that would ideally answer the causal question of interest; second, explicitly emulating this protocol using observational data [32]. By forcing researchers to articulate a precise causal question and design before analysis, this framework helps avoid common methodological pitfalls that have historically led to dramatic failures of observational inference, such as the erroneous protective effects of hormone therapy on coronary heart disease initially reported in observational studies but later contradicted by RCTs [32].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the target trial emulation approach against conventional observational methods, detailing its implementation protocols, experimental validation, and essential methodological tools for researchers and drug development professionals working within the evolving landscape of RWE validation for HTA.

Core Components of the Target Trial Framework

The target trial framework requires researchers to meticulously define all components of a hypothetical RCT that would answer their causal question. The table below outlines the key components that must be specified in the protocol, their role in the target trial, and how they are emulated with observational data [32] [35].

Table 1: Core Protocol Components of a Target Trial and Their Emulation

| Protocol Component | Role in the Target Trial | Emulation with Observational Data |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility Criteria | Defines the study population at time zero (start of follow-up) using only baseline information. | Apply identical criteria to select individuals from the observational database at their time zero. |

| Treatment Strategies | Precisely defines the interventions or treatment regimens being compared. | Identify individuals in the database whose treatment records align with the strategies. |

| Treatment Assignment | Randomization ensures comparability between treatment groups. | Use adjustment methods (e.g., weighting) to control for confounding and emulate randomization. |

| Outcome | Defines the primary outcome of interest and how it is measured. | Map the outcome definition to available data items (e.g., diagnosis codes, lab values). |

| Follow-up Period | Specifies the start, end, and duration of follow-up for each participant. | Define the start of follow-up (time zero) and censor at the earliest of: outcome, end of follow-up, or loss to data. |

| Causal Contrast | Defines the causal effect of interest (e.g., intention-to-treat or per-protocol effect). | Specify the same contrast and use appropriate statistical methods to estimate it. |

| Analysis Plan | Describes the statistical analysis for estimating the causal effect. | Implement an analysis (e.g., cloning/censoring/weighting) that accounts for the observational nature of the data. |

The power of this framework lies in its discipline. A conventional observational analysis might start with the data and fit a model, whereas a target trial emulation starts with a scientific question and designs a perfect study to answer it, only then looking to the data to execute that design [36]. This "question-first" approach is fundamental to generating evidence that can reliably inform regulatory and HTA decisions [34].

A Comparative Experiment: Target Trial Emulation vs. Conventional Methods

A landmark cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic provides a compelling experimental comparison of target trial emulation against conventional model-first approaches [36].

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

- Research Question: What is the association of a corticosteroid treatment regimen with 28-day mortality for hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19?

- Benchmark: The World Health Organization (WHO) meta-analysis of RCTs on corticosteroids, which found an odds ratio of 0.66 (95% CI, 0.53-0.82) [36].

- Data Source: Retrospective data from 3,298 patients hospitalized within the NewYork-Presbyterian hospital system between March and May 2020 [36].

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Designs Compared

| Methodology | Core Approach | Treatment Definition | Analytical Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Trial Emulation | Question-first, emulating a hypothetical RCT. | A 6-day corticosteroid regimen initiated if and when a patient met severe hypoxia criteria. | Doubly robust estimation. |

| Model-First (Cox Regression) | Model-first, using common clinical literature designs. | Varied definitions: no time frame, 1-day, and 5-day windows from time of severe hypoxia. | Cox Proportional Hazards model. |

Target Trial Emulation Protocol:

- Eligibility: Adult patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, excluding those with chronic corticosteroid use or transfers from outside hospitals.

- Treatment Strategies: A dynamic regimen (6 days of corticosteroids if/when severe hypoxia criteria are met) versus a static regimen (no corticosteroids).

- Outcome: All-cause mortality within 28 days of hospitalization.

- Causal Contrast: The per-protocol risk difference.

- Analysis: A doubly robust estimator was used to account for confounding, combining models for both the treatment and outcome to ensure validity even if one model is misspecified [36].

Results and Comparative Performance

The results demonstrated a stark contrast in the ability of each method to recover the established benchmark from RCTs.

Table 3: Comparison of Results Against the RCT Benchmark

| Analytical Method | Estimate of Corticosteroid Effect | Alignment with RCT Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| WHO RCT Meta-Analysis (Benchmark) | Odds Ratio = 0.66 (95% CI, 0.53-0.82) | Gold Standard |

| Target Trial Emulation | Risk: 25.7% (Treated) vs. 32.2% (Untreated); qualitatively identical to benchmark. | High Alignment |

| Cox Model (Various Specifications) | Hazard Ratios ranged from 0.50 (95% CI, 0.41-0.62) to 1.08 (95% CI, 0.80-1.47). | Low/Inconsistent Alignment |

The target trial emulation successfully recovered a treatment effect that was qualitatively identical to the RCT benchmark, demonstrating a clear reduction in 28-day mortality. In contrast, the hazard ratios from the conventional Cox models varied widely in both size and direction depending on the treatment definition used, failing to provide a consistent or reliable estimate [36]. This experiment underscores that the correctness of estimates from observational data depends more on the design principles and causal question formulation than on the specific model fitted to the data.

Implementing the Framework: A Practical Workflow

Successfully implementing the target trial framework requires a structured workflow. The diagram below visualizes this process from conceptualization to result interpretation.

Addressing Critical Methodological Challenges

A key challenge in emulation is ensuring the alignment of three critical time points: eligibility assessment, treatment assignment, and the start of follow-up (time zero). A review of 199 studies explicitly aiming to emulate target trials found that 49% had misalignment of these time points. Among these, 67% did not use any method to correct for this misalignment in their analysis, introducing a significant risk of bias [37].

Common Biases from Misalignment:

- Immortal Time Bias: Occurs when the start of follow-up precedes treatment assignment, creating a period where the outcome cannot occur (the patient is "immortal") in the treated group by design [33]. For example, in a study of antidepressants and manic switch, if follow-up starts at depression diagnosis but treatment begins later, the treated group has a guaranteed survival period that the control group does not [33].

- Prevalent User Bias: Occurs when follow-up starts for patients who are already using a treatment ("prevalent users"), who may differ systematically from new users, for instance, by having already tolerated the treatment well [33].

Solutions for Time Alignment: The cloning, censoring, and weighting approach is a sophisticated method to address time-related biases by creating copies ("clones") of participants at the point of eligibility and then using statistical weighting to emulate a randomized assignment over time [37] [38]. Alternatively, researchers can design the emulation so that a participant's time zero is precisely the moment they meet all eligibility criteria and are assigned to a treatment strategy.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Target Trial Emulation

Implementing this framework requires a specific set of methodological "reagents." The following table details essential components of the research toolbox for a successful target trial emulation.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Target Trial Emulation

| Tool Category | Specific Method/Technique | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Sequential Trials / Cloning-Censoring-Weighting | Manages time-varying treatments and confounders; corrects for time alignment issues. |

| Confounding Control | Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) | Creates a pseudo-population where treatment assignment is independent of measured confounders. |

| Confounding Control | G-Methods (G-Formula, Marginal Structural Models) | Adjusts for both baseline and time-varying confounding, even when affected by prior treatment. |

| Censoring Handling | Inverse Probability of Censoring Weighting (IPCW) | Corrects for selection bias introduced by loss to follow-up or other forms of censoring. |

| Estimation | Doubly Robust Estimation (e.g., Targeted Maximum Likelihood) | Combines outcome and treatment models to provide a valid estimate even if one model is misspecified. |

| Software & Algorithms | The Target Trial Toolbox (e.g., from Yale PEW) | Provides curated, easy-to-use algorithms for implementing the above designs and analyses. |

| (3S,4S)-PF-06459988 | (3S,4S)-PF-06459988, CAS:1428774-45-1, MF:C19H22ClN7O3, MW:431.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PhIP-d3 | PhIP-d3, CAS:210049-13-1, MF:C13H12N4, MW:227.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

These tools move beyond conventional regression modeling by directly addressing the structural biases inherent in observational data. Their use is critical for generating effect estimates that can be meaningfully interpreted as causal [36] [38].

Validation and Acceptance in Regulatory and HTA Contexts

The ultimate test for any RWE methodology is its acceptance by regulatory and HTA bodies. Frameworks like FRAME (Framework for Real-World Evidence Assessment to Mitigate Evidence Uncertainties for Efficacy/Effectiveness) are being developed to standardize the evaluation of RWE submissions [24]. Furthermore, leading HTA agencies such as the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) explicitly recommend designing non-randomized studies "to emulate the preferred randomised controlled trial (target trial approach)" [34].

This institutional endorsement signals a paradigm shift. The focus is moving from a default skepticism of all observational data to a critical appraisal of how well a study is designed to answer a specific causal question, with the target trial framework providing the necessary structural rigor. This is particularly vital for use cases like supporting single-arm trials with external controls, assessing effectiveness in broader populations, and generating evidence in rare diseases where RCTs are not feasible [24] [34].

The target trial framework is not merely another statistical technique but a fundamental shift in approach—from a model-first to a question-first paradigm. As the experimental comparison shows, this approach, when implemented with careful attention to protocol specification and time-related biases, can yield estimates from observational data that align with those from gold-standard RCTs. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the tools and workflows of target trial emulation is no longer optional but essential for generating the valid, impactful real-world evidence required by modern regulators, payers, and HTA bodies.

In the evaluation of health technologies and interventions, the gold standard for establishing efficacy is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). However, RCTs are often too complex, expensive, unethical, or simply infeasible for many large-scale policy interventions and real-world clinical settings [39]. In these circumstances, researchers increasingly turn to quasi-experimental designs and advanced causal inference methods to estimate treatment effects from observational data [14] [39]. These methodologies provide powerful alternatives when random assignment is not possible, allowing researchers to draw causal inferences from real-world data (RWD) that can inform health technology assessment (HTA) and policy decisions [40].

The growing importance of real-world evidence (RWE) in regulatory and HTA decision-making has accelerated the adoption of these methods [14]. As health systems increasingly rely on evidence beyond traditional clinical trials, understanding the strengths, limitations, and proper application of quasi-experimental designs and g-methods becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals [40]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these advanced causal methods, their experimental protocols, and their application within the context of RWE validation for HTA research.

Quasi-Experimental Designs: Theory and Applications

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Quasi-experimental designs are research methodologies that lie between the rigor of true experiments and the flexibility of observational studies [41]. Unlike RCTs where investigators randomly assign participants to groups, quasi-experiments evaluate interventions without random assignment, often leveraging naturally occurring circumstances that create experimental and control groups [41] [42]. The defining feature that distinguishes quasi-experiments from other observational designs is that they specifically evaluate the impact of a clearly defined event or process which results in differences in exposure between groups [42].

These designs are particularly valuable when investigating real-world interventions such as policy changes, health system reforms, or large-scale public health initiatives where randomization is impractical or unethical [41] [39]. For example, studying the health impacts of natural disasters, evaluating the effect of a new hospital funding model, or assessing the effectiveness of a public health campaign are all scenarios well-suited to quasi-experimental approaches [41] [39] [42].

Core Quasi-Experimental Designs: Methodologies and Protocols

Interrupted Time Series (ITS)

Experimental Protocol: ITS analysis identifies intervention effects by comparing the level and trend of outcomes before and after an intervention at multiple time points [39]. The design requires collecting data at regular intervals both pre- and post-intervention.

Model Specification: The basic ITS model can be represented as [39]: Yâ‚œ = β₀ + βâ‚T + β₂Xâ‚œ + β₃TXâ‚œ + εₜ Where Yâ‚œ is the outcome at time t, T is time since study start, Xâ‚œ is a dummy variable representing the intervention (0 = pre, 1 = post), and TXâ‚œ is the interaction term.

Key Elements: β₀ represents the baseline outcome level, β₠captures the pre-intervention trend, β₂ estimates the immediate level change following intervention, and β₃ quantifies the change in trend post-intervention [39].

Application Example: Researchers used ITS to evaluate the impact of Activity-Based Funding on patient length of stay following hip replacement surgery in Ireland, analyzing data points before and after the policy implementation in 2016 [39].

Difference-in-Differences (DiD)

Experimental Protocol: DiD estimates causal effects by comparing outcome changes between a treatment group exposed to an intervention and a control group not exposed, both before and after the intervention [39].

Design Requirements: The method requires at least two groups (treatment and control) and two time periods (pre- and post-intervention). The key assumption is that both groups would have followed parallel trends in the absence of the intervention.

Implementation: When studying Ireland's Activity-Based Funding reform, researchers used private patients as a control group since they continued to be reimbursed under the previous per-diem system, while public patients transitioned to the new DRG-based funding model [39].

Analysis: The DiD estimator is calculated as: (YÌ„treatment,post - YÌ„treatment,pre) - (YÌ„control,post - YÌ„control,pre).

Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD)

Experimental Protocol: RDD assigns participants to treatment based on a cutoff score of a pretreatment variable, comparing outcomes between individuals just above and below the threshold [43] [42].

Key Elements: This design capitalizes on the assumption that individuals immediately on either side of the cutoff are fundamentally similar except for their treatment eligibility [43].

Application Example: A study of England's RSV vaccination program used RDD by leveraging the sharp age cutoff at 75 years to create a natural experiment. Researchers compared hospitalization rates between individuals just above and below the eligibility threshold to isolate the vaccine's causal effect [43].

Pretest-Posttest Design with Control Group

Experimental Protocol: In this widely used quasi-experimental design, researchers select a treatment group and a control group with similar characteristics [41]. Both groups complete a pretest, the treatment group receives the intervention, and then both groups complete a posttest.

Methodological Considerations: It is ideal if the groups' mean scores on the pretest are similar (p-value > .05), and researchers should compare demographic characteristics and other variables that might influence posttest scores [41].

Application Example: To assess the impact of an app-based game on memory in older adults, participants from Senior Center A used the game while those from Senior Center B continued usual activities. Both groups underwent memory tests before and after the 30-day intervention period [41].

G-Methods for Complex Longitudinal Data

Theoretical Foundation and Need for Advanced Methods

When using observational data to estimate causal effects of treatments on clinical outcomes, researchers must adjust for confounding variables. In the presence of time-dependent confounders that are affected by previous treatment, adjustments cannot be made via conventional regression approaches or standard propensity score methods [44]. These scenarios require more sophisticated approaches known collectively as g-methods [44].

Time-dependent confounding occurs when a variable influences both future treatment and the outcome, while also being affected by past treatment. This creates a situation where traditional adjustment methods lead to biased estimates. G-methods were developed specifically to address this challenge, enabling estimation of the causal effects of treatment strategies defined by treatment at multiple time points [44].

Key G-Methods: Approaches and Protocols

The G-Formula

Experimental Protocol: The g-formula (or parametric g-formula) involves simulating potential outcomes under different treatment strategies by modeling the outcome conditional on treatment and covariate history, then standardizing results to the observed covariate distribution [44].

Implementation Steps:

- Model the conditional distribution of outcomes given treatment history and time-dependent covariates.

- Model the distribution of time-dependent covariates given prior treatment and covariate history.

- Simulate outcomes for the population under different treatment strategies using these models.

- Compare average outcomes across strategies to estimate causal effects.

Key Assumptions: The method relies on exchangeability (no unmeasured confounding), consistency (well-defined interventions), and positivity (all treatments possible at all levels of covariates) [44].

Inverse Probability-Weighted Marginal Structural Models

Experimental Protocol: This approach uses inverse probability weights to create a pseudo-population in which the distribution of time-dependent confounders is balanced across treatment groups, breaking the association between past treatment and current confounders [44].

Implementation Steps:

- Model treatment assignment at each time point conditional on past covariate history.

- Calculate inverse probability of treatment weights for each participant.

- Fit a marginal structural model (typically a weighted regression) for the outcome as a function of treatment history.

- Use the model to estimate outcomes under different treatment strategies.

Application Context: These methods are particularly valuable in neurosurgical research and other clinical settings where treatment decisions evolve over time based on patient response and changing clinical characteristics [44].

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Method Performance and Application Contexts

Table 1: Comparison of Quasi-Experimental Designs and Their Applications

| Method | Key Features | Data Requirements | Primary Applications | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interrupted Time Series | Analyzes pre- and post-intervention trends | Multiple observations pre- and post-intervention | Policy evaluations, system-level interventions [39] | No other concurrent changes affecting outcome |

| Difference-in-Differences | Compares changes between treatment and control groups | Pre/post data for both groups | Natural policy experiments, regional implementations [39] | Parallel trends between groups |

| Regression Discontinuity | Exploits sharp eligibility thresholds | Data around cutoff point | Program evaluations with clear eligibility rules [43] | Continuity of potential outcomes at cutoff |

| Synthetic Control | Constructs weighted comparator from multiple units | Panel data for treatment and pool of control units | Evaluating interventions affecting single units (states, countries) [39] | No unmeasured time-varying confounding |

Table 2: Comparison of G-Methods for Time-Dependent Confounding

| Method | Approach | Strengths | Limitations | Suitable Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-Formula | Simulates outcomes under treatment strategies | Handles complex interactions; direct standardization | Requires correct specification of multiple models | Long-term treatment effects; dynamic treatment regimes [44] |

| Inverse Probability-Weighted MSMs | Weighting to balance confounders | Simpler model specification; handles time-varying confounding | Unstable weights with strong confounding; positivity violations | Sustained treatment comparisons; complex longitudinal data [44] |

Empirical Performance and Validation

A comprehensive comparison of four quasi-experimental methods evaluating Ireland's introduction of Activity-Based Funding revealed important differences in performance and interpretation [39]. The study focused on length of stay following hip replacement surgery and found that:

- Interrupted Time Series analysis produced statistically significant results suggesting a reduction in length of stay, differing in interpretation from control-treatment methods [39].

- Difference-in-Differences, Propensity Score Matching DiD, and Synthetic Control methods incorporating control groups suggested no statistically significant intervention effect on patient length of stay [39].

- This comparison highlights that different analytical methods for estimating intervention effects can provide substantially different assessments of the same intervention [39].

These findings underscore the importance of employing appropriate designs that incorporate a counterfactual framework, as methods with control groups tend to be more robust and provide a stronger basis for evidence-based policy-making [39].

Implementation in Real-World Evidence Generation

Methodological Integration in Health Technology Assessment

The use of quasi-experimental designs and g-methods in RWE generation for HTA requires careful attention to methodological rigor and validation. Several frameworks have been developed to improve the acceptability of these approaches [40]: