Validating Mixed Treatment Comparisons: A Framework for Confirming MTC Results with Direct Evidence

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC) and Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) results against direct evidence.

Validating Mixed Treatment Comparisons: A Framework for Confirming MTC Results with Direct Evidence

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC) and Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) results against direct evidence. It covers foundational concepts of MTC, explores key methodological approaches for both fixed-effect and random-effects models, and details techniques for detecting and resolving statistical inconsistency within evidence networks. The content further examines comparative frameworks for assessing MTC validity and discusses the practical acceptance of these analyses by Health Technology Assessment (HTA) bodies. By synthesizing current methodologies and good research practices, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and credibility of indirect treatment comparisons in biomedical research.

The What and Why of Mixed Treatment Comparisons: Foundations for Validation

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), also known as Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC), represents an advanced statistical methodology that synthesizes evidence from multiple clinical trials to compare three or more interventions simultaneously within a single, coherent analytical framework [1] [2]. This approach represents a significant evolution beyond traditional pairwise meta-analysis by integrating both direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (estimated through a common comparator) to derive comprehensive treatment effect estimates across all competing interventions [3] [4]. The fundamental objective of MTC/NMA is to generate an internally consistent set of relative effect estimates for all treatment comparisons while respecting the randomization within the original trials [5]. This methodology has become increasingly valuable to clinicians, researchers, and healthcare decision-makers who need to determine the most effective interventions among multiple options, especially when direct comparison evidence is limited or nonexistent [1] [2].

The development of MTC/NMA methodology has progressed through several key stages. The initial foundation was laid with the introduction of adjusted indirect treatment comparisons by Bucher et al. in 1997, which provided a method for comparing interventions A and C through a common comparator B [1]. This was subsequently expanded by Lumley, who developed techniques for indirect comparisons utilizing multiple common comparators, introducing the concept of "incoherence" (later termed inconsistency) to measure disagreement between different evidence sources [1]. The most sophisticated methodological framework was established by Lu and Ades, who formalized mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis within a Bayesian framework, enabling simultaneous inference regarding all treatments and providing probability estimates for treatment rankings [3] [1]. This evolution has transformed evidence synthesis by allowing for more comprehensive and precise comparisons of multiple competing healthcare interventions.

Fundamental Concepts and Methodological Framework

Key Terminology and Definitions

Table 1: Essential Terminology in Network Meta-Analysis

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Direct Treatment Comparison | Comparison of two interventions using studies that directly compare them in head-to-head trials [1]. |

| Indirect Treatment Comparison | Estimate derived using separate comparisons of two interventions against a common comparator [1]. |

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) | Simultaneous comparison of three or more interventions incorporating both direct and indirect evidence [1] [4]. |

| Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC) | Synonym for NMA; specifically refers to networks where both direct and indirect evidence inform effect estimates [1]. |

| Transitivity | The core assumption that different sets of randomized trials are similar, on average, in all important factors other than the intervention comparison being made [4]. |

| Consistency | Statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison [6] [4]. |

| Inconsistency | Statistical disagreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison [6] [7]. |

Statistical Foundation and Evidence Structures

The statistical foundation of MTC/NMA relies on the principle that indirect comparisons can be mathematically derived from direct evidence. In a simple three-treatment scenario with interventions A, B, and C, where direct evidence exists for A vs. B and A vs. C, the indirect estimate for B vs. C can be calculated as the difference between the direct estimates: δBC = δAC - δAB, where δ represents the treatment effect [4]. This relationship preserves the within-trial randomization and forms the basis for more complex network structures. When four or more interventions are involved, indirect estimates can be derived through multiple pathways, with the only requirement that interventions are "connected" within the evidence network [4].

MTC/NMA can be implemented using both frequentist and Bayesian statistical frameworks, with the latter being particularly common in applied research [1]. Bayesian approaches typically employ Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods implemented in software like WinBUGS, and allow for the estimation of posterior probability distributions for all treatment effects and rankings [3]. These models can incorporate both fixed-effect and random-effects assumptions, with random-effects models accounting for heterogeneity in treatment effects across studies by assuming that the true effects come from a common distribution [3] [6]. The Bayesian framework also facilitates the calculation of ranking probabilities for each treatment, indicating the probability that an intervention is the best, second best, etc., for a given outcome [1] [2].

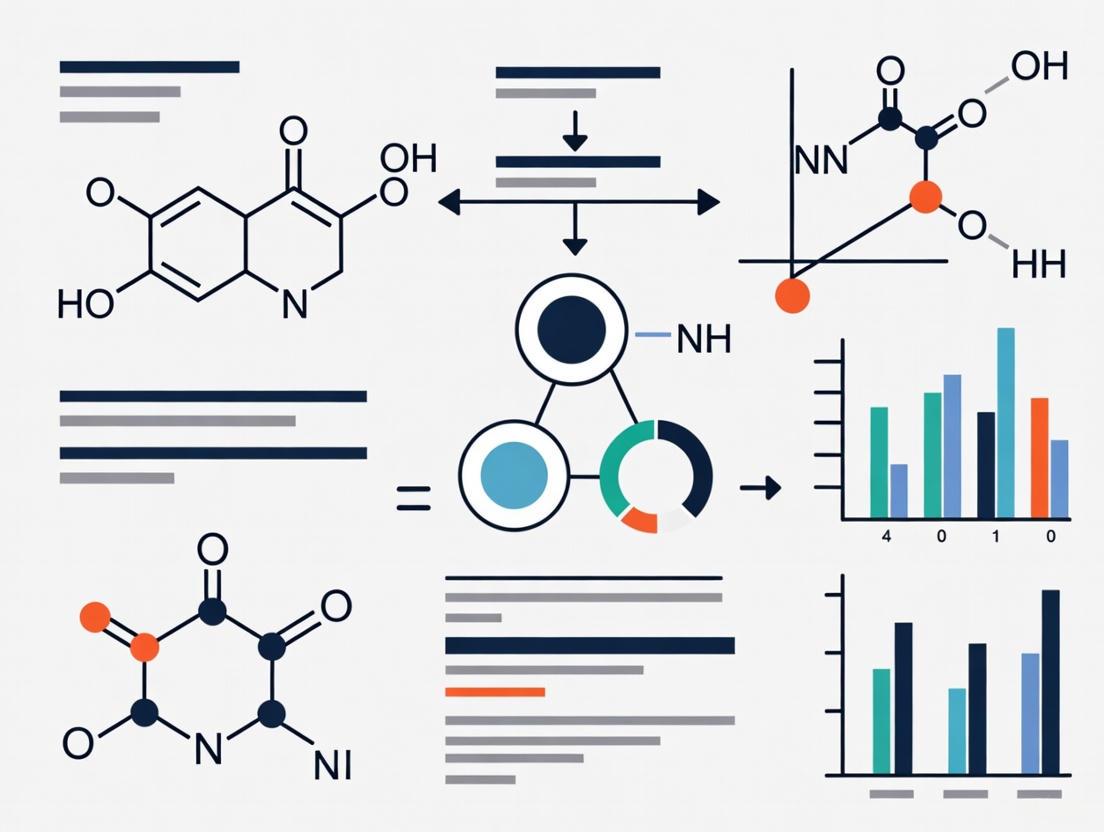

Figure 1: Network Diagram Showing Direct and Indirect Evidence Pathways. Solid lines represent direct evidence from head-to-head trials, while dashed lines represent indirect evidence pathways derived through common comparators.

Core Assumptions: Transitivity and Consistency

The Transitivity Assumption

Transitivity forms the fundamental conceptual assumption underlying the validity of indirect comparisons and MTC/NMA [4]. This assumption requires that the different sets of randomized trials included in the network are similar, on average, in all important factors that may modify treatment effects [4]. In practical terms, transitivity implies that we could potentially imagine a three-arm trial comparing A, B, and C that would yield similar results to what we obtain by combining separate A vs. B and A vs. C trials [6]. Violations of transitivity occur when study characteristics that modify treatment effects differ systematically across the various direct comparisons in the network.

Several factors can threaten the transitivity assumption, including differences in patient characteristics (e.g., disease severity, age, comorbidities), intervention modalities (e.g., dosage, administration route, treatment duration), study methodologies (e.g., blinding, outcome assessment, follow-up duration), or contextual factors (e.g., standard care, publication year, setting) across trials comparing different interventions [6]. For example, if trials comparing A vs. B were conducted in severe disease populations while trials comparing A vs. C were conducted in mild disease populations, and disease severity modifies treatment effects, the transitivity assumption would be violated. Assessing transitivity requires careful examination of the distribution of potential effect modifiers across the different direct comparisons in the network [4].

Consistency and Inconsistency

Consistency refers to the statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison, representing the statistical manifestation of the transitivity assumption [6] [4]. When both direct and indirect evidence exist for a particular comparison, consistency implies that these different sources of evidence provide similar estimates of the treatment effect. Inconsistency (sometimes termed incoherence) occurs when direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison disagree beyond what would be expected by chance alone [6] [7]. The presence of significant inconsistency threatens the validity of the network meta-analysis and suggests potential violation of the transitivity assumption or other methodological issues.

Methodologists have identified different types of inconsistency in network meta-analyses. Loop inconsistency refers to disagreement between different sources of evidence within closed loops of the network, typically involving three treatments where both direct and indirect evidence exist for all comparisons [6]. Design inconsistency arises when the effect estimates differ depending on the design of the studies (e.g., two-arm trials vs. multi-arm trials) contributing to the comparison [6]. Higgins et al. have proposed that the concept of design-by-treatment interaction provides a useful general framework for investigating inconsistency, particularly when multi-arm trials are present in the evidence network [6]. This approach successfully addresses complications that arise from the presence of multi-arm trials, which complicate traditional definitions of loop inconsistency [6].

Methodological Approaches for Evaluating Consistency

Statistical Methods for Detecting Inconsistency

Table 2: Methods for Assessing Consistency in Network Meta-Analysis

| Method | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Node-Splitting | Separates direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons and tests for significant differences [8] [7]. | Focused assessment of inconsistency at specific comparisons; useful for pinpointing sources of disagreement. |

| Design-by-Treatment Interaction | Evaluates whether treatment effects differ across study designs (e.g., two-arm vs. multi-arm trials) [6]. | Comprehensive approach particularly valuable when network contains multi-arm trials; provides global inconsistency assessment. |

| Loop-Specific Approach | Assesses inconsistency within each closed loop of three treatments in the network [7]. | Traditional method suitable for simple networks; limited utility with multi-arm trials. |

| Net Heat Plot | Graphical tool identifying hot spots of inconsistency and influential comparisons [7]. | Visual diagnostic method for locating inconsistency sources and understanding their impact on network estimates. |

| Bayesian Inconsistency Factors | Incorporates random inconsistency factors into the model within a Bayesian framework [7]. | Sophisticated approach that quantifies and incorporates uncertainty about inconsistency in the analysis. |

Implementation of Consistency Checks

Implementing consistency checks begins with a global test of inconsistency, which assesses whether there is any detectable inconsistency anywhere in the network [7]. The design-by-treatment interaction model provides a comprehensive framework for this global assessment, testing whether treatment effects differ systematically across various study designs in the network [6]. If global inconsistency is detected, local inconsistency methods are applied to identify specific comparisons or loops where inconsistency occurs. Node-splitting methods are particularly valuable for this purpose, as they allow meta-analysts to separate direct and indirect evidence for each comparison and test whether they differ significantly [8].

The implementation of these methods requires careful consideration of statistical modeling choices. For example, in node-splitting models, different parameterizations can yield slightly different results when multi-arm trials are involved [8]. The symmetrical method assumes that both treatments in a comparison contribute to inconsistency, while asymmetrical parameterizations assume that only one of the two treatments contributes to the inconsistency [8]. Similarly, when using design-by-treatment interaction models, the definition of inconsistency degrees of freedom may vary depending on whether direct evidence from two-armed and multi-armed studies is distinguished [7]. These technical considerations highlight the importance of involving experienced statisticians in the implementation of consistency assessments.

Figure 2: Methodological Workflow for Consistency Evaluation in Network Meta-Analysis. This flowchart illustrates the systematic approach to assessing and addressing inconsistency in MTC/NMA, from initial global tests to specific resolution strategies.

Experimental Validation and Application Framework

Case Study: Nutrition Labelling Interventions

A comprehensive network meta-analysis by Song et al. (2021) demonstrates the practical application of MTC methodology to evaluate the impact of different nutrition labelling schemes on consumers' purchasing behavior [9]. This analysis incorporated 156 studies (including 101 randomized controlled trials and 55 non-randomized studies) comparing multiple front-of-package labelling interventions, including traffic light labelling (TLS), Nutri-Score (NS), nutrient warnings (NW), and health warnings (HW) [9]. The researchers performed both direct pairwise meta-analyses and network meta-analyses to synthesize the evidence, allowing for comparison of results from different methodological approaches.

The analysis revealed important differences in intervention effectiveness that informed policy recommendations. The study found that all labelling schemes were associated with improved consumer choices, but with different strengths: colour-coded labels (TLS and NS) performed better in promoting the purchase of more healthful products, while warning labels (NW and HW) were more effective in discouraging unhealthful purchasing behavior [9]. The network meta-analysis allowed for simultaneous comparison of all labelling types, even those that had not been directly compared in primary studies, providing a comprehensive evidence base for policy decisions. The researchers assessed consistency between direct and indirect evidence and explored potential effect modifiers, such as study setting (real-world vs. laboratory) and outcome measurement, to validate the transitivity assumption [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodological Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for MTC/NMA Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | Bayesian analysis using MCMC methods; implements models described by Lu & Ades [3]. |

| R packages (gemtc, netmeta) | Frequentist and Bayesian approaches; comprehensive NMA implementation [7]. | |

| Stata NMA modules | Statistical implementation for network meta-analysis and inconsistency assessment. | |

| Consistency Assessment | Node-splitting models | Direct evaluation of inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence [8]. |

| Design-by-treatment interaction | Framework for inconsistency assessment addressing multi-arm trials [6]. | |

| Net heat plot | Graphical inconsistency localization and driver identification [7]. | |

| Quality Assessment | GRADE for NMA | Structured approach for rating confidence in network estimates [10] [2]. |

| Risk of Bias tools | Study-level methodological quality assessment (e.g., Cochrane RoB tool). | |

| Visualization | Network diagrams | Evidence structure representation with nodes and edges [4]. |

| Rankograms/SUCRA | Graphical presentation of treatment ranking probabilities [1] [2]. | |

| 3,6-Dihydroxyflavone | 3,6-Dihydroxyflavone|High-Purity Research Compound | |

| 6-Methoxywogonin | 6-Methoxywogonin, CAS:3162-45-6, MF:C17H14O6, MW:314.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Protocol for Validating MTC Results with Direct Evidence

Define the Network Geometry: Create a network diagram specifying all treatments and direct comparisons, identifying all closed loops where both direct and indirect evidence exist [4] [7]. Document the number of studies contributing to each direct comparison and note potential systematic differences in study characteristics across comparisons.

Assess Transitivity Assumption: Systematically evaluate the distribution of potential effect modifiers across the different direct comparisons in the network [4]. Consider patient characteristics, intervention modalities, outcome definitions, study methodologies, and contextual factors that might modify treatment effects.

Implement Consistency Models: Apply both global and local inconsistency tests using appropriate statistical methods [6] [7]. For networks with multi-arm trials, prioritize design-by-treatment interaction models over simple loop-based approaches [6]. Use node-splitting for focused assessment of specific comparisons of interest.

Conduct Sensitivity Analyses: Perform analyses excluding studies with high risk of bias, different study designs, or specific populations to assess the robustness of findings to these factors [4] [5]. Explore the impact of alternative statistical models (fixed vs. random effects) on consistency assessments.

Interpret and Resolve Inconsistency: If significant inconsistency is detected, investigate potential causes through subgroup analyses or meta-regression [4] [7]. Consider excluding studies contributing to inconsistency if justified by methodological concerns, and report any remaining inconsistency with appropriate caveats for interpretation.

This systematic approach to validation ensures that MTC/NMA results are rigorously evaluated against direct evidence, strengthening the credibility of conclusions derived from mixed treatment comparisons. When properly implemented with careful attention to consistency assessment, MTC/NMA provides a powerful tool for comparative effectiveness research that respects the randomization in the underlying evidence while maximizing the use of all available information [2] [5].

The Critical Role of Direct Evidence in the Validation Framework

Mixed treatment comparison (MTC), more commonly known as network meta-analysis (NMA), is an advanced statistical methodology that synthesizes both direct and indirect evidence to estimate the comparative efficacy and safety of multiple interventions [11]. In an MTC, the term "mixed" refers to the analytical combination of direct evidence (from head-to-head randomized controlled trials) and indirect evidence (from trials that compare interventions of interest via a common comparator) within a single evidence network [12] [11]. This approach allows for the comparison of multiple treatments simultaneously, even when some pairs of treatments have never been directly compared in clinical trials.

While MTCs provide a powerful tool for comparative effectiveness research, they rely on a critical assumption: consistency between direct and indirect evidence [12] [13]. When this assumption is violated—a situation termed "incoherence" or "inconsistency"—the validity of MTC results becomes questionable [12]. Incoherence occurs when estimates based on direct comparisons meaningfully differ from those derived through indirect comparisons [12]. This fundamental vulnerability necessitates a robust validation framework centered on direct evidence, which serves as the benchmark for assessing the reliability of mixed treatment comparisons.

The Critical Role of Direct Evidence in Validation

Direct Evidence as the Validation Gold Standard

Direct evidence, obtained from well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compare treatments head-to-head, represents the gold standard for establishing comparative efficacy in clinical research [14]. In the context of MTC validation, direct evidence provides the reference point against which mixed treatment estimates are evaluated. This validation process is essential because MTCs incorporate additional methodological assumptions that extend beyond those required for standard pairwise meta-analyses [12].

The integration of direct evidence into a validation framework serves several critical functions. First, it enables the detection of statistical inconsistency within an evidence network. Second, it provides a mechanism for identifying potential effect modifiers that may vary across studies and influence treatment comparisons. Third, it enhances the robustness and credibility of MTC findings for healthcare decision-makers, including regulatory agencies and health technology assessment bodies [14].

Methods for Validating MTCs with Direct Evidence

Inconsistency Detection and Analysis

A fundamental approach to validating MTC results involves formally testing for inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence. Statistical methods for inconsistency detection include:

- Node-splitting techniques: Separately estimating treatment effects from direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons and testing for significant differences [13]

- Design-by-treatment interaction models: Assessing whether treatment effects vary by trial design or other study-level characteristics

- Back-calculation methods: Comparing direct estimates from trials with those derived from the network meta-analysis model

When direct and indirect evidence demonstrate consistency, confidence in MTC findings increases substantially. However, when incoherence is detected—where direct comparison estimates fall outside the confidence intervals of corresponding indirect comparison estimates—investigators must explore potential explanations before relying on the mixed treatment estimates [12].

Hierarchical Validation Approach

A comprehensive validation framework for MTCs employs a hierarchical approach across three levels:

- Study-level validation: Critical appraisal of individual RCTs included in the evidence network for risk of bias, methodological quality, and relevance to the research question [12]

- Comparison-level validation: Assessment of transitivity and similarity assumptions across studies contributing to each treatment comparison [12]

- Network-level validation: Evaluation of the overall consistency of the evidence network and exploration of potential sources of heterogeneity

This multi-layered approach ensures that validation occurs at every stage of the MTC process, with direct evidence serving as the anchor point at each level.

Consequences of Inadequate Validation

Failure to properly validate MTC findings against direct evidence can lead to misleading conclusions and potentially harmful healthcare decisions. Empirical studies have demonstrated that discrepancies between direct and indirect evidence are not merely theoretical concerns. For instance, in a comparison of 12 antidepressants, conclusions based solely on indirect evidence were substantially different from those based on direct comparisons [12]. Similarly, in a network meta-analysis of opioid detoxification treatments, MTC techniques produced narrower confidence intervals than direct comparisons alone, creating an illusion of precision that could mask important uncertainties [12].

Experimental Protocols for MTC Validation

Protocol for Consistency Assessment

Objective: To statistically evaluate the consistency between direct and indirect evidence for each treatment comparison within a network meta-analysis.

Methodology:

- Identify all treatment comparisons with both direct and indirect evidence

- Extract or calculate effect estimates and measures of precision for each direct comparison

- Derive indirect estimates using the Bucher method or similar approaches [14]

- Statistically compare direct and indirect estimates using node-split models or similar techniques

- Quantify the degree of inconsistency using appropriate statistical measures (e.g., inconsistency factors, p-values)

- Investigate potential clinical or methodological explanations for any detected inconsistencies

This protocol enables researchers to identify specific comparisons where direct and indirect evidence diverge, guiding further investigation into potential causes.

Protocol for Sensitivity Analysis with Direct Evidence

Objective: To assess the robustness of MTC findings by comparing results from different evidence configurations.

Methodology:

- Conduct the primary analysis including all available evidence (both direct and indirect)

- Perform sensitivity analyses restricted to:

- Only direct evidence where available

- Evidence from studies with low risk of bias

- Studies with similar patient populations and methodologies

- Compare effect estimates, ranking probabilities, and between-study heterogeneity across different analyses

- Evaluate whether conclusions regarding comparative efficacy remain consistent across sensitivity analyses

This protocol helps determine whether MTC findings are unduly influenced by specific studies or types of evidence, with direct evidence serving as a key benchmark.

Signaling Pathways and Methodological Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core methodological workflow for validating mixed treatment comparisons through integration with direct evidence:

MTC Validation Workflow

This workflow demonstrates how direct evidence serves as the critical validation checkpoint within the MTC analytical process. The consistency assessment phase represents the core validation mechanism where direct and indirect evidence are formally compared.

Comparative Analysis of MTC Validation Methods

The table below summarizes the key methodological approaches for validating mixed treatment comparisons using direct evidence:

Table 1: Methods for Validating Mixed Treatment Comparisons with Direct Evidence

| Validation Method | Application Context | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node-Splitting [13] | Local inconsistency detection for specific comparisons | Pinpoints exact location of inconsistency in network | Limited power in sparse networks | Both direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons |

| Design-by-Treatment Interaction [13] | Global inconsistency assessment across entire network | Comprehensive network evaluation | Does not identify specific inconsistent comparisons | Network with varied study designs |

| Bucher Method [14] | Simple indirect comparisons and validation | Simple implementation and interpretation | Limited to simple indirect comparisons | Two treatments vs. common comparator |

| Sensitivity Analysis [12] | Robustness assessment of MTC findings | Assesses impact of evidence sources on conclusions | Does not provide formal statistical tests | Multiple evidence configurations |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MTC Validation

Table 2: Key Methodological Tools for MTC Validation

| Tool/Technique | Primary Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Network Meta-Analysis Software (e.g., R, WinBUGS) [13] | Statistical implementation of MTC models | Provides specialized routines for inconsistency detection and analysis |

| The Bucher Method [14] | Simple indirect treatment comparisons | Creates benchmark indirect estimates for comparison with direct evidence |

| Risk of Bias Tools (e.g., Cochrane RoB) [12] | Quality assessment of individual studies | Identifies methodological limitations that may explain inconsistency |

| Node-Split Models [13] | Statistical detection of local inconsistency | Formally tests differences between direct and indirect evidence |

| Network Graphs | Visualization of evidence structure | Identifies gaps in direct evidence and potential violations of similarity |

| T-1330 | T-1330, CAS:106461-41-0, MF:C22H27N5O2, MW:393.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Hydroxy Atorvastatin Lactone-d5 | 2-Hydroxy Atorvastatin Lactone-d5, CAS:265989-50-2, MF:C33H33FN2O5, MW:561.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Direct evidence serves as the cornerstone of validation for mixed treatment comparisons, providing an essential benchmark against which the reliability of complex evidence networks is assessed. The integration of direct evidence within a comprehensive validation framework enables researchers to detect inconsistencies, investigate their sources, and enhance the credibility of MTC findings. As health technology assessment agencies and regulatory bodies increasingly consider MTCs in their decision-making processes [14], robust validation methodologies centered on direct evidence become increasingly critical. Future methodological developments should focus on enhancing inconsistency detection methods, standardizing validation reporting, and establishing clearer guidelines for when MTC findings can be considered sufficiently validated for healthcare decision-making.

In evidence-based medicine, Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC), also known as Network Meta-Analysis, has emerged as a powerful statistical tool for comparing the efficacy of multiple treatments simultaneously, even when direct head-to-head trials are unavailable [5] [15]. This methodology allows for the integration of both direct and indirect evidence into a single, coherent analysis, facilitating complex treatment decisions and supporting health technology assessments [14] [15]. The validity of any MTC, however, rests upon three fundamental and interrelated core assumptions: similarity, homogeneity, and consistency. Understanding and verifying these assumptions is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to ensure the reliability of MTC results, particularly when confirming findings with direct evidence research.

The Triad of Core Assumptions

The foundational pillars of MTC define the conditions under which different clinical trials can be legitimately combined and compared within a network. The following table summarizes these core concepts.

Table 1: Core Assumptions of Mixed Treatment Comparisons

| Assumption | Definition | Primary Concern | Key Question for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity | The assumption that different trials are sufficiently similar in their study-level characteristics (moderators) to permit comparison [16]. | Transitivity across the network | Are the trials comparing different treatments similar enough in terms of patient populations, trial design, and outcomes measurement? [16] |

| Homogeneity | The assumption that trials estimating the same treatment comparison are measuring the same underlying treatment effect [15] [16]. | Variability within pairwise comparisons | Is the treatment effect for a specific head-to-head comparison similar across all trials that study it? |

| Consistency | The assumption that direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (derived via a common comparator) are in agreement [15] [16]. | Coherence between direct and indirect evidence | For the same treatment comparison, do the direct and indirect estimates provide the same result? |

Similarity: The Foundation of Transitivity

The similarity assumption forms the logical basis for building a connected network of trials. It requires that the trials included for different treatment comparisons are sufficiently similar in their moderating factors to allow for a fair comparison. In practice, this means that the relative treatment effects being studied should not be influenced by systematic differences in trial design or patient characteristics across the network [16]. For instance, an MTC would be violated if all trials comparing Treatment A to Treatment B were conducted in a population with severe disease, while all trials comparing Treatment A to Treatment C were conducted in a population with mild disease.

Methodological Protocol for Assessing Similarity:

- Identify Potential Effect Modifiers: Systematically identify and record clinical and methodological variables that could modify the treatment effect. These commonly include patient demographics (e.g., age, disease severity, comorbidities), trial characteristics (e.g., duration, blinding, setting), and definitions of outcomes.

- Evaluate Distribution of Modifiers: Examine the distribution of these effect modifiers across the different treatment comparisons in the network. This can be done through summary tables or visual inspection of the study-level characteristics grouped by comparison.

- Statistical Evaluation: While there is no single statistical test for similarity, its violation can contribute to inconsistency. Exploring the distribution of modifiers is a key step in diagnosing the root cause of any inconsistency detected in the network.

Homogeneity: Consistency Within Comparisons

Homogeneity is directly analogous to the assumption underlying a standard pairwise meta-analysis. It posits that the true treatment effect is the same across all trials that directly compare the same two interventions. Significant heterogeneity suggests that the studies are not estimating a single common effect, which may be due to clinical or methodological diversity among the trials [15].

Methodological Protocol for Assessing Homogeneity:

- Visual Inspection: Use forest plots for each direct pairwise comparison to visually assess the overlap of confidence intervals and the point estimates of individual studies.

- Statistical Tests: Calculate the I² statistic and Cochran's Q for each direct comparison. The I² statistic describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. An I² value greater than 50% may be considered substantial heterogeneity.

- Subgroup Analysis and Meta-Regression: If significant heterogeneity is detected, researchers can use subgroup analysis or meta-regression to explore the influence of specific study-level covariates on the observed treatment effects.

Consistency: The Harmony of Direct and Indirect Evidence

The consistency assumption is unique to the MTC framework and is critical for its validity. It requires that the direct estimate of a treatment effect (from head-to-head trials) is consistent with the indirect estimate of the same effect (obtained through a common comparator) [15] [16]. When this assumption holds, the combined evidence from the network is coherent.

Methodological Protocol for Assessing Consistency:

- Design-by-Treatment Interaction Test: A global test that assesses inconsistency across the entire network model. A significant result suggests a violation of the consistency assumption somewhere in the network.

- Node-Splitting Method: This is a local test for inconsistency. It separately calculates the direct, indirect, and MTC estimates for a specific treatment comparison and then tests for a significant difference between the direct and indirect estimates [5].

- Bucher's Method: For a simple closed loop of three treatments (A, B, C), this method provides a statistical test to compare the direct estimate of A vs. B with the indirect estimate obtained via C [5] [14]. The analysis of an overview of treatments for childhood nocturnal enuresis found that summary estimates based on fixed-effect meta-analyses were "highly inconsistent," whereas those based on random-effects models were consistent [5].

The logical relationships between evidence types and the core assumptions that govern them can be visualized in the following workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MTC Analysis

Conducting a robust MTC requires a suite of statistical and computational tools. The following table details key "research reagents" and their functions in the analytical process.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for MTC Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application in MTC |

|---|---|---|---|

| WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | Software | Bayesian statistical analysis using MCMC simulation. | The historical software of choice for fitting Bayesian MTC models, as used in foundational methodology papers [3] [16]. |

| R (with packages) | Software/Programming Language | Statistical computing and graphics. | Modern, flexible environment for conducting MTCs. Packages like gemtc and pcnetmeta facilitate network meta-analysis and inconsistency testing. |

| PRISMA-NMA Guideline | Reporting Guideline | A checklist and framework for reporting. | Ensures transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses incorporating network meta-analyses [15]. |

| Node-Split Model | Statistical Model | A local test for inconsistency. | Separately estimates the direct and indirect evidence for a specific comparison within the network to test their consistency [5]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | Computational Algorithm | A method for sampling from a probability distribution. | Used in Bayesian MTC to estimate the posterior distributions of model parameters, such as relative treatment effects [16]. |

| 5-Nitrouracil | 5-Nitrouracil CAS 611-08-5|Research Chemical | Bench Chemicals | |

| Rsu 1164 | Rsu 1164, CAS:105027-77-8, MF:C10H16N4O3, MW:240.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The assumptions of similarity, homogeneity, and consistency are not mere statistical formalities; they are the critical safeguards that ensure the validity and interpretability of Mixed Treatment Comparisons. For drug development professionals and researchers, a thorough investigation of these assumptions is a non-negotiable component of the MTC process. This involves meticulous study design, comprehensive data collection, and the application of robust statistical methods to evaluate these assumptions. By rigorously confirming that these core principles are upheld, scientists can have greater confidence in the results of an MTC, especially when using them to triangulate findings from direct evidence research, ultimately leading to more reliable and informed healthcare decisions.

In an era of rapidly expanding therapeutic options, clinicians and healthcare decision-makers are consistently faced with a fundamental challenge: determining the optimal treatment among multiple alternatives without adequate direct comparative evidence. Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC), also known as network meta-analysis, has emerged as a crucial methodological framework that addresses this evidence gap by enabling the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions, even when direct head-to-head trials are absent or limited [17]. This advanced analytical approach represents a significant evolution beyond traditional pairwise meta-analysis, allowing researchers to synthesize both direct evidence (from trials comparing treatments directly) and indirect evidence (from trials connected through common comparators) within a unified statistical model [18] [19].

The proliferation of treatment options, particularly in complex disease areas like oncology and rare diseases, has intensified the need for sophisticated comparative effectiveness methodologies. As noted by the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons, "Evidence-based health-care decision making requires comparisons of all relevant competing interventions" [19]. MTC fulfills this need by creating a connected network of evidence where interventions can be compared through both direct and indirect pathways, thereby synthesizing a greater share of the available evidence than traditional meta-analytic approaches [17] [19]. This comprehensive synthesis is particularly valuable for health technology assessment (HTA) agencies and formulary committees tasked with making coverage decisions amidst constrained healthcare resources.

Fundamental Methodological Framework of MTC

Core Concepts and Terminology

MTC methodology operates on several fundamental concepts that form the backbone of its analytical approach:

Network Meta-Analysis: A generic term defining the simultaneous synthesis of evidence for all pairwise comparisons across more than two interventions [17]. This approach creates a connected network where every intervention can be compared to every other intervention through direct or indirect pathways.

Closed Loop: A network structure where at least one pair of treatments has both direct evidence (from trials directly comparing them) and indirect evidence (through connected pathways via common comparators) [17]. For example, if treatment A has been compared to B in some trials, B to C in others, and A to C in yet others, the AC comparison forms a closed loop with both direct and indirect evidence.

Indirect Treatment Comparison (ITC): The estimation of relative treatment effects between two interventions that have not been directly compared in randomized trials but have been connected through a common comparator [18] [14]. The simplest form of ITC is the anchored indirect comparison described by Bucher et al., which allows comparison of interventions that have been evaluated against a common control in separate trials [17].

Bayesian Framework: A statistical approach commonly used for MTC that combines prior probability distributions (reflecting prior belief about possible values of model parameters) with likelihood distributions based on observed data to obtain posterior probability distributions [17]. This framework naturally accommodates complex network structures and provides intuitive probabilistic interpretations of results.

Key Statistical Assumptions

The validity of MTC analyses depends on several critical statistical assumptions that must be carefully evaluated:

Similarity Assumption: Trials included in the network must be sufficiently similar in terms of interventions, patient populations, outcome definitions, and study design characteristics to allow meaningful comparison [18]. Violations of this assumption can introduce bias and compromise the validity of results.

Homogeneity Assumption: For each pairwise comparison, the treatment effect should be reasonably consistent across trials (statistical homogeneity) [18]. When heterogeneity is present, random-effects models can incorporate between-study variance, though this does not explain the sources of heterogeneity.

Consistency Assumption: The direct and indirect evidence for a particular treatment comparison should be in agreement [19]. Inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence suggests potential effect modifiers or methodological issues within the network.

Table 1: Key Methodological Assumptions in Mixed Treatment Comparisons

| Assumption | Definition | Implications for Validity |

|---|---|---|

| Similarity | Trials are sufficiently comparable in design, patients, interventions, and outcomes | Ensures comparisons between trials are clinically meaningful |

| Homogeneity | Treatment effects are consistent across studies for each pairwise comparison | Affects choice between fixed-effect and random-effects models |

| Consistency | Agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison | Violations suggest potential bias or effect modification |

Experimental and Analytical Protocols

Network Meta-Analysis Workflow

The implementation of MTC follows a structured workflow that ensures methodological rigor and transparency. The following diagram illustrates the key stages in conducting a network meta-analysis:

Detailed Methodological Approaches

Bayesian Implementation

The Bayesian framework for MTC involves specifying prior distributions for model parameters and updating these priors with observed data to obtain posterior distributions [17]. This approach typically utilizes Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods implemented in specialized software such as WinBUGS, OpenBUGS, or JAGS. The Bayesian approach offers several advantages, including natural handling of complex random-effects structures, straightforward probability statements for treatment rankings, and flexible accommodation of various data types. Model convergence must be carefully assessed using diagnostic statistics such as Gelman-Rubin statistics, and posterior distributions should be based on sufficient MCMC iterations after convergence is achieved.

Frequentist Implementation

Frequentist approaches to MTC, such as Lumley's network meta-analysis method, utilize mixed models to combine direct and indirect evidence when at least one closed loop exists in the evidence network [17]. These methods often employ generalized linear mixed models and can be implemented in standard statistical software such as R or SAS. Frequentist approaches provide maximum likelihood estimates of treatment effects and confidence intervals based on asymptotic normality assumptions. While potentially more familiar to many researchers, they may be less flexible than Bayesian methods for handling complex random-effects structures or making probabilistic statements about treatment rankings.

Validation Through Comparison with Direct Evidence

A critical component of MTC methodology involves confirming results through comparison with direct evidence when available. This validation process includes:

Consistency Testing: Statistical evaluation of agreement between direct and indirect evidence for treatment comparisons where both types of evidence exist [19]. Methods for assessing consistency include node-splitting approaches, which separate direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons, and design-by-treatment interaction models.

Empirical Evaluation: Comparison of MTC results with findings from subsequent direct comparative trials when they become available. This real-world validation provides important evidence regarding the predictive performance of MTC in various clinical contexts.

Sensitivity Analyses: Conducting analyses under different statistical assumptions, inclusion criteria, or model specifications to assess the robustness of MTC findings. These analyses help determine whether conclusions are sensitive to methodological choices or specific studies in the network.

Table 2: MTC Validation Techniques and Their Applications

| Validation Technique | Methodological Approach | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Node-Splitting | Separates direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons | Inconsistency suggests potential bias or effect modification |

| Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model | Global test for consistency across the entire network | Significant p-value indicates overall inconsistency |

| Comparison with Direct Evidence | Empirical comparison with head-to-head trials when available | Assesses predictive validity of MTC methods |

| Meta-Regression | Adjusts for trial-level covariates | Reduces heterogeneity and inconsistency when effect modifiers are identified |

Comparative Analysis of Indirect Treatment Comparison Methods

The methodological landscape for indirect treatment comparisons has expanded significantly, with multiple techniques now available for different evidence scenarios. A 2024 systematic literature review identified seven distinct ITC techniques reported in the literature, with varying frequencies of application [14]:

Table 3: Indirect Treatment Comparison Techniques and Applications

| ITC Technique | Frequency of Description | Key Applications | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) | 79.5% | Connected networks of RCTs with multiple interventions | Aggregate data from multiple trials |

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) | 30.1% | Single-arm studies with heterogeneous populations | Individual patient data (IPD) for index treatment |

| Network Meta-Regression (NMR) | 24.7% | Networks with suspected effect modifiers | Aggregate data plus trial-level covariates |

| Bucher Method | 23.3% | Simple connected networks with common comparator | Aggregate data from two trials with common comparator |

| Simulated Treatment Comparison (STC) | 21.9% | Single-arm studies with limited comparator data | IPD for index treatment, aggregate for comparator |

| Propensity Score Matching (PSM) | 4.1% | Non-randomized comparisons with limited RCT data | IPD for all treatment groups |

| Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) | 4.1% | Non-randomized comparisons with confounding | IPD for all treatment groups |

Selection Criteria for ITC Methods

The appropriate choice of ITC technique depends on several factors related to the available evidence base and research question:

Network Connectivity: The presence of a connected network where all treatments are linked through direct or indirect pathways favors NMA approaches. Disconnected networks may require population-adjusted methods like MAIC or STC [14].

Availability of Individual Patient Data (IPD): When IPD is available for at least one treatment, MAIC and STC become feasible options. These methods can adjust for cross-trial differences in patient characteristics through reweighting or matching techniques [14].

Between-Study Heterogeneity: Substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity across studies may necessitate random-effects models or meta-regression approaches to account for between-study variability [18].

Number of Relevant Studies: Networks with limited numbers of studies may be unsuitable for complex random-effects models, requiring simpler approaches like the Bucher method for basic indirect comparisons.

Implementing MTC analyses requires familiarity with specialized statistical software and methodological resources. The following tools represent essential components of the methodological toolkit for researchers conducting mixed treatment comparisons:

Table 4: Essential Resources for MTC Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/References | Application in MTC |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | WinBUGS/OpenBUGS, JAGS, R (gemtc, netmeta, pcnetmeta packages) | Bayesian and frequentist model implementation |

| Methodological Guidance | ISPOR Task Force Reports, NICE DSU Technical Support Documents | Best practices for design, analysis, and interpretation |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, GRADE for NMA | Assessing validity and quality of evidence |

| Data Extraction Support | Systematic review management software (DistillerSR, Covidence) | Efficient data collection and management |

| Visualization Tools | Network graphs, rank probability plots, contribution plots | Visual representation of networks and results |

Applications in Evidence-Based Medicine: Case Examples

Oncology Applications

MTC methodologies have been particularly valuable in oncology, where rapid therapeutic advances and multiple treatment options create decision-making challenges with limited direct comparative evidence. A review of MTC applications in oncology identified six published analyses between 2006-2010 spanning various cancer types including ovarian, colorectal, breast, and non-small cell lung cancer [18]. These analyses demonstrated the ability of MTC to synthesize evidence across complex therapeutic landscapes and provide comparative effectiveness estimates for clinical decision-making.

For example, an MTC analysis in advanced breast cancer published in 2008 synthesized evidence from 172 randomized controlled trials involving 22 different interventions [18]. This comprehensive analysis allowed for simultaneous comparison of multiple treatment regimens and provided valuable insights into their relative effects on overall survival. Similarly, an MTC in ovarian cancer analyzed 60 RCTs of 120 different interventions, demonstrating the ability of these methods to handle networks of substantial complexity [18].

Confirming MTC Results with Direct Evidence

The critical test of any indirect comparison method lies in its agreement with direct evidence when it becomes available. Empirical evaluations have generally shown reasonable agreement between properly conducted MTC analyses and subsequent direct comparisons, though discrepancies can occur when key assumptions are violated.

Several studies have compared the results of indirect comparisons with direct evidence, with varying degrees of concordance. The circumstances under which MTC results align with direct evidence include:

Similar Patient Populations: When trials in the network enroll clinically similar populations with comparable baseline risk profiles [18].

Consistent Outcome Definitions: When outcome assessments, follow-up durations, and measurement approaches are consistent across trials.

Absence of Effect Modifiers: When no important treatment effect modifiers are distributed differently across the direct and indirect comparisons.

Conversely, MTC results may diverge from direct evidence when there are important differences in trial design, patient characteristics, or outcome assessments that introduce heterogeneity or inconsistency into the network.

Future Directions and Methodological Challenges

As MTC methodologies continue to evolve, several areas represent important frontiers for methodological development and application:

Individual Patient Data Network Meta-Analysis: The integration of IPD into MTC models offers potential advantages for exploring treatment-effect heterogeneity, assessing individual-level predictors of treatment response, and improving the adjustment for cross-trial differences [14].

Complex Evidence Structures: Methods for handling increasingly complex evidence networks, including multi-arm trials, combination therapies, and treatment sequences, represent an active area of methodological research.

Real-World Evidence Integration: Approaches for incorporating real-world evidence alongside randomized trial data in MTC models may enhance the generalizability and completeness of comparative effectiveness assessments.

Decision-Theoretic Framework: Enhanced methods for integrating MTC results with formal decision-analytic modeling to support healthcare resource allocation decisions.

Despite these advances, important challenges remain in the implementation and interpretation of MTC analyses. These include the need for clearer international consensus on methodological standards, improved transparency in reporting, and continued education for stakeholders involved in healthcare decision-making [14]. As the field progresses, the utility and transparency of MTC methodologies will likely predict their continued uptake by the research and clinical communities [18].

Executing and Analyzing MTCs: Statistical Methods and Good Research Practices

In the context of mixed treatment comparisons (MTCs) and network meta-analysis, the choice between fixed-effect and random-effects models is foundational, influencing the robustness and interpretation of your results when confirming findings with direct evidence. This choice determines whether you are estimating a single universal treatment effect or an average of effects that genuinely vary across studies, populations, and settings.

The distinction is philosophical as much as it is statistical. A fixed-effect model assumes that all studies in your analysis are estimating the same single, true effect size. Variations in individual study results are attributed solely to within-study sampling error. Conversely, a random-effects model assumes that the true effect size itself varies from study to study, and your analysis aims to estimate the mean of this distribution of true effects [20] [21].

This framework is critical for MTCs, which rely on indirect evidence to compare treatments. The model you select dictates how you handle heterogeneity—the variability between studies—which can arise from differences in patient populations, treatment dosages, or study methodologies. Proper model selection ensures that the uncertainty in your indirect comparisons is accurately quantified, which is essential for validating them against any available direct evidence.

Conceptual Foundation and When to Choose

Defining the Models and Their Assumptions

Your choice of model hinges on your assumptions about the data and the goals of your analysis.

Fixed-Effect Model: This model is built on the assumption that every study in your meta-analysis is functionally identical in design, methods, and patient samples, and that all are measuring the same underlying true effect [20]. Any observed differences between study results are presumed to be due entirely to chance (sampling error within studies). It answers the question: "What is the best estimate of this common effect size?"

Random-Effects Model: This model acknowledges that studies are often meaningfully dissimilar. It assumes that each study has its own true effect size, drawn from a distribution of effects [20] [21]. The model explicitly accounts for two sources of variation: the within-study sampling error (as in the fixed-effect model) and the between-study variance in true effects (often denoted as τ², or tau-squared). It answers the question: "What is the average of the varying true effects?"

Decision Framework: Which Model to Use and When

The decision should be made a priori, based on conceptual reasoning about the included studies, and not based on the observed heterogeneity after running the analysis [20] [21].

The following workflow outlines the key questions to guide your model selection:

In practice, for mixed treatment comparisons where studies often differ in design, comparator treatments, and patient characteristics, a random-effects model is frequently the more appropriate and conservative choice [15] [14]. It better accounts for the clinical and methodological diversity expected across a network of studies.

Impact on Analysis and Interpretation

Consequences for Study Weights, Estimates, and Precision

The choice of model directly impacts how studies are weighted in the meta-analysis and the resulting pooled estimate.

- Study Weights: In a fixed-effect model, weights are based almost exclusively on study precision (typically, inverse variance). Larger studies with narrower confidence intervals receive disproportionately greater weight. In a random-effects model, weights are more balanced between large and small studies because the model incorporates the between-study variance, reducing the relative dominance of very large studies [20].

- Pooled Estimate and Confidence Intervals: The random-effects model generally produces a pooled estimate with a wider confidence interval than the fixed-effect model. This is because it accounts for an additional source of uncertainty—the between-study variance [20] [21]. Consequently, a result that is statistically significant under a fixed-effect model may become non-significant under a random-effects model.

Table: Comparative Impact of Model Choice on Meta-Analysis Output

| Aspect | Fixed-Effect Model | Random-Effects Model |

|---|---|---|

| Assumed True Effects | One single true effect | A distribution of true effects |

| Source of Variance | Within-study sampling error only | Within-study + between-study variance |

| Weighting of Studies | Heavily favors larger, more precise studies | More balanced between large and small studies |

| Confidence Intervals | Narrower | Wider |

| Interpretation of Result | Estimate of the common effect | Estimate of the mean of the distribution of effects |

| Generalizability | Limited to the specific set of studied populations | More generalizable to a wider range of settings |

The Critical Role of Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity (I²) statistics quantify the proportion of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. While a high I² value might suggest a random-effects model is needed, it should not be the sole driver of your model choice. The decision must be primarily conceptual [21]. A random-effects model is the correct choice when you have reason to believe true effects differ, regardless of the calculated I² value.

A more informative approach in a random-effects framework is to report a prediction interval. While a confidence interval indicates the uncertainty around the estimated mean effect, a prediction interval estimates the range within which the true effect of a new, similar study would be expected to fall. This provides a more realistic picture of the treatment effect's variability in practice [21].

Methodological Protocols and Statistical Considerations

Experimental and Analytical Protocols

Implementing a robust meta-analysis requires a pre-specified, systematic protocol.

- Protocol Registration: The choice between fixed-effect and random-effects models should be specified in advance, ideally in a registered protocol (e.g., with PROSPERO) [20].

- Systematic Review: Conduct a comprehensive literature search following PRISMA guidelines to identify all relevant studies [15] [14]. Data extraction should be blinded and pre-specified.

- Data Extraction and Quality Assessment: Extract data in a standardized format. Assess study quality using tools like the Jadad scale to inform sensitivity analyses [15].

- Statistical Analysis:

- For Random-Effects: Choose an appropriate estimator for the between-study variance (τ²). The Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) and Paule-Mandel (PM) estimators are generally preferred over the older DerSimonian-Laird (DL) method, which can underestimate uncertainty with few studies [21].

- For Confidence Intervals: When using a random-effects model, the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) method for confidence intervals is recommended as it provides better coverage when the number of studies is small [21].

- Sensitivity Analysis: It is good practice to run both fixed-effect and random-effects models and report the results of both, especially if the conclusions differ [20]. This demonstrates the robustness (or lack thereof) of your findings.

Essential Reagents for the Research Toolkit

Table: Key Methodological Tools for Meta-Analysis

| Tool or Method | Function | Considerations for Model Choice |

|---|---|---|

| PRISMA Guidelines | Ensures transparent and complete reporting of the systematic review and meta-analysis. | Mandatory for publishing; framework is independent of model. |

| Cochroke Handbook | Provides comprehensive guidance on conduct of meta-analysis. | Advocates for random-effects as a default in many clinical contexts. |

| I² Statistic | Quantifies the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity. | Descriptive tool; should not dictate model choice. |

| REML / PM Estimators | Advanced methods to estimate between-study variance (τ²) in random-effects models. | Preferred over DL for better accuracy, especially with few studies. |

| HKSJ Method | A modified method to calculate confidence intervals in random-effects meta-analysis. | Provides more robust intervals with a small number of studies. |

| Prediction Intervals | Estimates the range of true effects in future settings. | Highly recommended for random-effects to show practical implications. |

| Atrazine-d5 | Atrazine-d5, CAS:163165-75-1, MF:C8H14ClN5, MW:220.71 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyrene-d10 | Pyrene-d10, CAS:1718-52-1, MF:C16H10, MW:212.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the context of confirming mixed treatment comparison results with direct evidence, the model you select fundamentally shapes your conclusions. The fixed-effect model offers a false sense of precision when its core assumption of a single true effect is violated, which is common in real-world clinical research. The random-effects model, by acknowledging and accounting for between-study differences, provides a more realistic and generalizable summary of the evidence.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the following is recommended:

- Default to a Random-Effects Model: Given the inherent clinical and methodological diversity in most networks of studies, a random-effects model is often the more appropriate and conservative starting point [20] [21].

- Justify Your Choice A Priori: Base your decision on the expected similarity of studies and the goal of your analysis, not on post-hoc heterogeneity statistics.

- Use Contemporary Methods: When applying a random-effects model, use robust variance estimators (e.g., REML, PM) and the HKSJ method for confidence intervals.

- Report Prediction Intervals: Move beyond the mean effect and report prediction intervals to communicate the expected range of effects in clinical practice.

- Conduct Sensitivity Analyses: Run both models to assess the robustness of your findings, particularly for key outcomes in your MTC.

By adhering to these principles, you will produce a more rigorous, reliable, and clinically applicable evidence synthesis, strengthening the validity of your indirect comparisons and their confirmation with direct evidence.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) represents a sophisticated evidence synthesis methodology that enables simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions within a single analytical framework. By integrating both direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (from trials connected through common comparators), NMA provides a powerful tool for comparative effectiveness research, particularly crucial for drug development professionals and researchers facing limited direct comparison data. This methodology has gained substantial traction across medical fields, with published guidance showing a significant increase since 2011, particularly on evidence certainty and NMA assumptions [22] [23]. The core strength of NMA lies in its ability to confirm mixed treatment comparison results through coherence between direct and indirect evidence, thereby generating a more comprehensive understanding of therapeutic relative effectiveness.

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Network Meta-Analysis

| Concept | Definition | Importance in MTC Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Evidence | Evidence from studies directly comparing interventions (e.g., A vs. B) | Serves as reference for validating indirect comparisons |

| Indirect Evidence | Evidence derived through a common comparator (e.g., A vs. B via C) | Extends inference to comparisons lacking head-to-head trials |

| Network Connectivity | The pattern of connections between interventions via direct comparisons | Ensures the feasibility of indirect and mixed treatment comparisons |

| Transitivity Assumption | The assumption that studies comparing different interventions are sufficiently similar in important effect modifiers | Foundational for valid indirect comparisons |

| Consistency/Coherence | Agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison | Critical for confirming mixed treatment comparison results |

Foundational Principles of Network Meta-Analysis

Core Assumptions and Statistical Framework

The validity of any NMA depends on three fundamental assumptions that researchers must rigorously assess. The transitivity assumption requires that studies comparing different interventions are sufficiently similar in clinical and methodological characteristics that could modify treatment effects. This implies that participants in any pairwise comparison could hypothetically have been randomized to any intervention in the network. The homogeneity assumption dictates that effect sizes for the same pairwise comparison do not differ significantly across studies, while the consistency assumption requires statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison [22].

The statistical framework for NMA typically employs hierarchical Bayesian or frequentist models that simultaneously analyze all direct and indirect comparisons. These models generate relative treatment effects with measures of precision for all possible pairwise comparisons within the network, even those never directly studied in trials. Recent methodological reviews indicate that guidance documents on assumptions and certainty of evidence have become particularly abundant, with over 13 documents per topic, providing robust resources for researchers implementing these techniques [22].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Protocol Development and Research Question Formulation

The initial phase of any NMA requires meticulous planning and protocol development, an area where methodological reviews have identified comparatively sparse guidance [22]. A well-structured protocol should explicitly define the research question using PICO elements (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome), specify the network geometry (all interventions of interest), and predefine the statistical methods for evaluation of assumptions.

Node-making – the process of defining and grouping interventions for analysis – represents a critical methodological choice, particularly for complex public health interventions. A recent methodological review proposed a typology of node-making elements organized around seven considerations: Approach, Ask, Aim, Appraise, Apply, Adapt, and Assess [24]. In practice, network nodes can be formed by:

- Grouping similar interventions or intervention types (65/102 networks in public health NMAs)

- Comparing named interventions directly (6/102)

- Defining nodes as combinations of intervention components (26/102)

- Using an underlying component classification system (5/102) [24]

Diagram 1: NMA Workflow Overview

Comprehensive Search and Study Selection

A rigorous systematic review constitutes the essential foundation for any valid NMA. This process requires comprehensive searches across multiple databases, grey literature sources, and clinical trial registries to minimize publication bias. Recent methodological guidance emphasizes the importance of specialized search strategies to identify all relevant randomized controlled trials for the interventions of interest, with emerging artificial intelligence-assisted tools showing promise in enhancing search sensitivity without sacrificing specificity [25] [26].

Study selection should follow the standard systematic review process of title/abstract screening followed by full-text assessment, ideally conducted independently by at least two reviewers using tools such as Covidence [22] [23]. The PRISMA-NMA reporting guidelines provide a structured framework for documenting the search and selection process, ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

Data Extraction and Transitivity Assessment

Data extraction for NMA extends beyond standard systematic reviews by requiring additional elements critical for assessing transitivity and potential effect modifiers. These include:

- Patient characteristics that may modify treatment effects (age, disease severity, comorbidities)

- Intervention details (dose, duration, delivery mode, concomitant treatments)

- Study methodology (design, setting, follow-up duration, outcome definitions)

- Result data for all relevant outcomes across all intervention groups

A proposed typology for node-making suggests that reviewers should "Appraise" potential effect modifiers and "Adapt" their analytical approach based on assessment of clinical and methodological diversity [24]. This assessment directly informs the evaluation of the transitivity assumption.

Table 2: Key Methodological Considerations at Each NMA Stage

| Stage | Key Considerations | Validation Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Development | Scope of network, node definition, outcomes, analysis plan | Peer review, registration (PROSPERO) |

| Search & Selection | Comprehensiveness, reproducibility, minimization of bias | PRISMA flow diagram, search strategy peer review |

| Transitivity Assessment | Clinical/methodological similarity, potential effect modifiers | Comparison of study characteristics across comparisons |

| Statistical Analysis | Model choice, heterogeneity, consistency evaluation | Sensitivity analyses, model fit statistics, node-splitting |

| Evidence Certainty | Risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, publication bias | GRADE for NMA approaches |

Network Geometry and Connectivity Evaluation

Before conducting statistical analyses, researchers must evaluate the network structure and connectivity. This involves creating a network diagram (as shown in Diagram 2) that visually represents all treatments and direct comparisons, with node size typically proportional to the number of patients and line thickness proportional to the number of studies for each direct comparison.

Diagram 2: Example Network Geometry

The arrangement of interventions in the network directly enables the confirmation of mixed treatment comparisons with direct evidence. For instance, in Diagram 2, the comparison between Drug A and Drug C has both direct evidence (2 trials) and indirect evidence through Placebo and Drug B, allowing statistical assessment of consistency between these evidence sources [24].

Statistical Analysis and Model Implementation

The analytical phase of NMA involves several sequential steps:

1. Model Selection: Choose between fixed-effect and random-effects models based on heterogeneity assessment. Random-effects models are generally preferred as they account for between-study heterogeneity.

2. Implementation: Most contemporary NMAs use Bayesian methods with Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation, though frequentist approaches are also available. Guidance resources for software implementation are most abundant for R and Stata packages [22] [23].

3. Ranking: Generate treatment hierarchies using metrics such as Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking Curve (SUCRA) or mean ranks, which estimate the probability of each treatment being the most effective.

4. Consistency Assessment: Evaluate agreement between direct and indirect evidence using statistical methods such as node-splitting, which separately estimates direct and indirect evidence for particular comparisons [22].

For complex interventions, reviewers may face methodological choices between 'splitting' versus 'lumping' interventions and between intervention-level versus component-level analysis. Additive component network meta-analysis models offer an alternative approach, though a review found these were applied in just 6 of 102 networks in public health [24].

Critical Appraisal and Certainty Assessment

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework for NMA provides a systematic approach for rating confidence in estimated effects. This approach categorizes interventions for each outcome based on their positioning from best to worst while considering both effect estimates and certainty of evidence [10]. The certainty rating begins with the assumption that direct evidence provides higher certainty than indirect evidence, then evaluates five factors:

- Risk of bias across studies contributing to the network

- Indirectness of the evidence for the specific research question

- Inconsistency in results (heterogeneity or inconsistency)

- Imprecision of effect estimates

- Publication bias across the network

A recent design validation study developed novel presentation formats for conveying this complex information, using color-coded shading to identify the magnitude and certainty of treatment effects in relation to reference treatments [10].

Results Presentation and Visualization

Effective communication of NMA findings requires specialized presentation approaches that can simultaneously display multiple outcomes and treatments. Through iterative design validation with clinicians, researchers have developed color-coded presentation formats that organize treatments by benefit and harm categories across outcomes [10]. These formats place treatment options in rows and outcomes in columns, with intuitive color coding to facilitate interpretation by audiences with limited NMA familiarity.

Emerging technologies are further enhancing presentation capabilities. Recent artificial intelligence-assisted systems can synthesize and present NMA results through interactive web platforms, though these require further validation against traditional methods [25] [26].

Case Study Application: Pharmacological Obesity Treatments

A recent high-quality NMA evaluated the efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatments for obesity, analyzing 56 randomized controlled trials with 60,307 patients [27]. This analysis exemplifies the complete NMA methodology:

Network Structure: The analysis compared six obesity medications (orlistat, semaglutide, liraglutide, tirzepatide, naltrexone/bupropion, and phentermine/topiramate) against placebo, with limited direct head-to-head comparisons (only liraglutide vs. orlistat and semaglutide vs. liraglutide).

Outcomes: The primary outcome was percentage of total body weight loss (TBWL%) with multiple secondary outcomes including lipid profile, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, and adverse events.

Validation of Results: The analysis demonstrated consistency between direct and indirect evidence where available, strengthening confidence in the mixed treatment comparisons. For instance, the direct comparison showing semaglutide superiority to liraglutide was consistent with indirect comparisons through placebo.

Findings: All medications showed significantly greater weight loss versus placebo, with only semaglutide and tirzepatide achieving more than 10% TBWL. The analysis provided crucial evidence for clinical decision-making by simultaneously ranking interventions across multiple efficacy and safety outcomes [27].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Resources for NMA

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Review Software | Covidence, Rayyan, DistillerSR | Study screening, selection, and data extraction management | Streamlining systematic review process with dual independent review |