Strategic Framework for Formulating Key Questions in Drug Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER)

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on formulating pivotal questions for Drug Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER).

Strategic Framework for Formulating Key Questions in Drug Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER)

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on formulating pivotal questions for Drug Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER). It outlines a strategic framework covering foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting for common challenges, and validation techniques. By addressing these four core intents, the guide aims to enhance the design, execution, and regulatory acceptance of CER studies, ultimately supporting the development of safe and effective medicines with robust, real-world evidence.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Regulatory Expectations for Drug CER

Understanding the Purpose of CER in the Drug Development Lifecycle

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) plays a pivotal role in the modern drug development lifecycle by generating evidence on the benefits and harms of available treatment options for specific patient populations. Framed within the context of formulating key research questions, CER moves beyond establishing whether a treatment works under ideal conditions (efficacy) to determine how it performs in real-world settings against alternative therapies (effectiveness). This in-depth guide explores the methodologies and standards for integrating CER throughout drug development to inform critical healthcare decisions.

The Fundamental Role of CER in Drug Development

CER transforms drug development from a linear process focused solely on regulatory approval to a more dynamic, evidence-driven lifecycle that emphasizes value to patients and healthcare systems. Its core purpose is to fill critical evidence gaps that exist after a drug's initial efficacy and safety are established, providing answers that are directly relevant to patients, clinicians, and payers [1]. This is achieved by comparing drugs, medical devices, tests, surgeries, or ways to deliver healthcare to determine which work best for which patients and under what circumstances [2].

The integration of CER is particularly crucial as the industry faces rising challenges, including the complexity of new therapies like cell and gene treatments, increased regulatory scrutiny, and pressure to contain costs [3]. By providing robust evidence on a treatment's real-world performance, CER helps maximize the return on investment in drug development by ensuring that new products can demonstrably improve patient outcomes relative to existing alternatives. Furthermore, a well-executed CER strategy supports the adoption of new therapies by providing the evidence needed for reimbursement decisions and clinical guideline development.

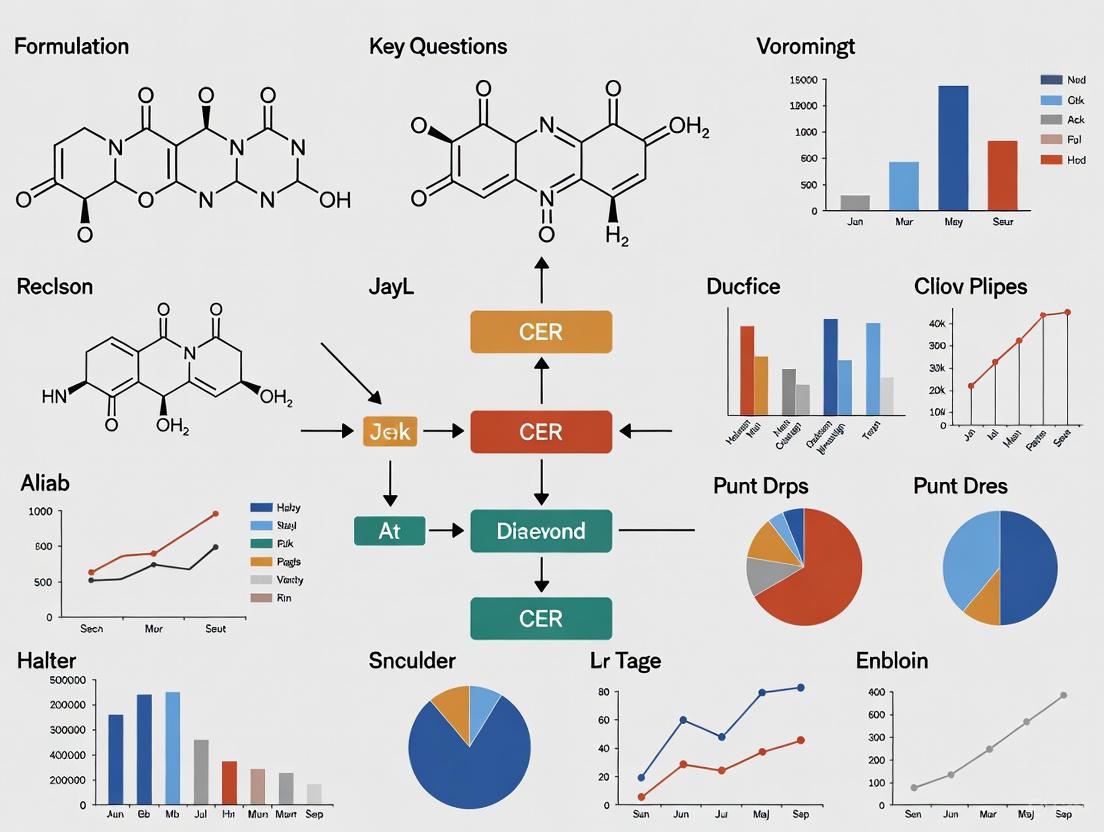

Formulating Key Questions for CER Studies

The foundation of valid and useful CER lies in the meticulous formulation of its research questions. This process ensures that the study addresses decisions of genuine importance and produces actionable results.

The PICOTS Framework

A structured approach to defining the research scope is the PICOTS framework, which delineates the Population, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, Timeframe, and Setting of the study [2]. This framework forces researchers to precisely define each component, reducing ambiguity and ensuring the research is fit-for-purpose to inform a specific health decision.

- Population: CER should strive to include participants representative of the spectrum of the population of interest, including those historically underrepresented in research [1]. This is critical for understanding how treatment effects may vary across subgroups.

- Interventions and Comparators: The interventions and comparators must correspond to actual healthcare options faced by patients and providers. "Usual care" or "non-use" comparator groups should generally be avoided unless they represent legitimate and coherent clinical options [1].

- Outcomes: CER must measure outcomes that the population of interest notices and cares about, such as survival, functioning, symptoms, and health-related quality of life [1]. These are known as patient-centered outcomes.

- Timeframe and Setting: The study duration and the real-world or routine practice setting in which it is conducted are essential for assessing the practical effectiveness of a treatment.

Engaging Stakeholders in Question Development

A hallmark of patient-centered CER is the early and meaningful engagement of stakeholders in formulating research questions. Stakeholders include individuals affected by the condition, their caregivers, clinicians, payers, and policy makers [1]. Their involvement increases the applicability of the study to end-users and facilitates the translation of results into practice [2]. Engaging patients helps ensure that the selected outcomes are truly meaningful to those living with the disease, moving beyond purely clinical or surrogate endpoints to those that impact daily life.

Synthesizing Evidence and Conceptualizing the Problem

Before designing a new CER study, researchers must conduct a comprehensive review and synthesis of the existing knowledge base. This involves identifying systematic reviews, critically appraising published studies, and pinpointing where evidence is absent, insufficient, or conflicting [2]. This synthesis justifies the need for the new research. Furthermore, developing a conceptual model or framework is recommended to diagram the theorized relationships between the treatment, outcome, and other key variables, which guides the entire study design [2].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols in CER

CER employs a variety of study designs, each with specific protocols tailored to generate robust real-world evidence.

Core CER Study Designs

| Study Design | Description | Key Protocol Considerations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials (Pragmatic) | Participants are randomly assigned to treatment groups in a real-world setting. | Design should align closely with routine clinical practice; broad eligibility criteria; use of patient-centered outcomes [4]. | Considered the gold standard for causal inference when feasible to conduct; ideal for head-to-head comparisons of active treatments. |

| Observational Studies | Analyzes data from real-world settings (e.g., EHRs, claims) without intervention. | Must use causal models (e.g., DAGs) to identify and control for confounding; clearly define "time zero" and follow-up to avoid immortal time bias [2] [5]. | When RCTs are not ethical or practical; to study long-term safety and effectiveness; to assess treatment effects in diverse populations. |

| Master Protocols (Umbrella, Basket, Platform) | Complex trials that evaluate multiple therapies or diseases within a single, overarching structure [6]. | Protocol must define biomarker stratification (umbrella), common molecular alteration (basket), or adaptive entry/exit of treatments (platform) [6]. | Accelerating development in precision medicine, especially in oncology and rare diseases with genetic markers. |

Visualization for Causal Inference and Study Design

Visual tools are critical for ensuring transparency and validity in CER, particularly in observational studies.

Causal Diagram (DAG)

Observational Study Timeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key resources required for conducting rigorous CER.

| Item/Resource | Function in CER | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Real-World Data (RWD) | Provides information on patient health status and/or delivery of healthcare from diverse sources. | Includes Electronic Health Records (EHRs), claims data, patient registries. Must be assessed for reliability (accuracy, completeness) and relevance (availability of key data elements) [5]. |

| Validated Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Measures | Instruments to directly capture the patient's perspective on their health status. | Must demonstrate content validity, construct validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change in the population of interest [1]. |

| Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) Tools | Software to create and analyze causal diagrams for identifying confounding variables. | Tools like DAGitty (free, web- or R-based) help identify the minimally sufficient set of covariates to control for to reduce bias [5]. |

| Standardized Protocol Templates | Provides a structured format for developing a detailed study protocol. | ICH M11 template (FDA recommended), NIH templates for clinical trials, and NCI templates for oncology studies ensure all key components are addressed [6]. |

| Glycinexylidide | Glycinexylidide, CAS:18865-38-8, MF:C10H14N2O, MW:178.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Creatine Monohydrate | Creatine Monohydrate|High-Purity Reagent|RUO | High-purity Creatine Monohydrate for research. Study energy metabolism, neuroprotection, and myopathies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Data Integrity, Visualization, and Regulatory Compliance

Maintaining the highest standards of data integrity is paramount for CER to be trusted by decision-makers.

Data Management and Analysis Plans

A formal Data Management Plan (DMP) is critical, specifying how data will be collected, organized, handled, preserved, and shared to ensure it is accessible and reproducible [1]. Furthermore, an a priori Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) must be specified in the study protocol before analysis begins. This includes defining key exposures, outcomes, covariates, plans for handling missing data, and approaches for subgroup and sensitivity analyses [1].

Regulatory and Reporting Standards

CER must adhere to evolving regulatory expectations for data presentation and transparency. The FDA has issued guidelines on standard formats for tables and figures in submissions to enhance clarity and consistency [7]. Furthermore, study results must be registered in public platforms like ClinicalTrials.gov and reported according to established guidelines such as CONSORT for randomized trials or STROBE for observational studies [1]. Engaging with regulatory agencies early through mechanisms like pre-ANDA meetings is encouraged, especially for complex products [8].

Integrating Comparative Effectiveness Research throughout the drug development lifecycle is no longer optional but essential for demonstrating the real-world value of new therapeutics. By rigorously formulating research questions using the PICOTS framework, engaging stakeholders, employing appropriate and transparent methodologies, and adhering to the highest standards of data integrity, researchers can generate the evidence needed to inform critical health decisions. This patient-centered approach ensures that the drug development process ultimately delivers not just new medicines, but treatments that truly improve outcomes that matter to patients.

Navigating Key FDA Regulatory Pathways and Guidance Documents

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides several regulatory pathways to facilitate efficient drug development and approval, particularly for serious conditions and rare diseases. Understanding these pathways is crucial for designing robust Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) that meets regulatory standards. These pathways balance the need for rigorous evidence with practical considerations for diseases where traditional randomized controlled trials may be infeasible. Recent innovations, including the Plausible Mechanism Pathway announced in November 2025, reflect FDA's evolving approach to evidence generation for targeted therapies [9] [10]. This guide examines key pathways, recent guidance documents, and methodological considerations essential for drug development professionals.

Core FDA Regulatory Pathways

Accelerated Approval Program

The Accelerated Approval Program allows earlier approval of drugs that treat serious conditions and fill an unmet medical need based on a surrogate endpoint [11]. A surrogate endpoint is a marker—such as a laboratory measurement, radiographic image, or physical sign—that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit but is not itself a measure of clinical benefit. This approach can considerably shorten the time required prior to receiving FDA approval.

- Post-Approval Requirements: Sponsors must conduct studies to confirm the anticipated clinical benefit. If confirmatory trials verify clinical benefit, the drug receives traditional approval. If not, FDA has regulatory procedures that could lead to removing the drug from the market [11].

- Applicability: This pathway is particularly valuable for diseases where long-term outcomes take considerable time to measure, but shorter-term surrogate endpoints have been validated.

Plausible Mechanism Pathway

Announced in November 2025, the Plausible Mechanism Pathway represents a significant shift in FDA's approach to bespoke therapies, especially for ultra-rare conditions where randomized trials are not feasible [9] [10]. This pathway operates under FDA's existing statutory authorities and requires clinical data meeting statutory standards of safety and efficacy.

The pathway is built around five core elements that must be demonstrated through successive patients with different bespoke therapies:

- Specific Molecular Abnormality: Identification of a specific molecular or cellular abnormality with a direct causal link to the disease, not a broad set of consensus diagnostic criteria [9] [10].

- Targeted Biological Alteration: The medical product must target the underlying or proximate biological alterations [9] [10].

- Characterized Natural History: Well-characterized natural history of the disease in the untreated population [9] [10].

- Confirmed Target Engagement: Evidence exists confirming that the target was successfully drugged or edited, which may come from biopsies or non-animal models [9].

- Clinical Improvement: Demonstration of improvement in clinical outcomes or disease course that excludes regression to the mean [9] [10].

- Postmarket Evidence Requirements: Sponsors must collect real-world evidence (RWE) to demonstrate preservation of efficacy, absence of off-target edits, effect of early treatment on childhood development milestones, and detection of unexpected safety signals [9].

- Therapeutic Scope: While initially focused on cell and gene therapies for rare childhood diseases, the pathway is also available for common diseases with no proven alternatives or considerable unmet need after available therapies [9] [10].

Rare Disease Evidence Principles (RDEP)

The Rare Disease Evidence Principles (RDEP) process, announced in September 2025, facilitates approval of drugs for rare diseases with known genetic defects that drive pathophysiology [9]. To be eligible, products must target conditions with:

- A known, in-born genetic defect as the major disease driver

- Progressive deterioration leading to significant disability or death

- Very small patient populations (e.g., fewer than 1,000 persons in the U.S.)

- Lack of adequate alternative therapies that alter disease course

Under RDEP, substantial evidence of effectiveness can be established through one adequate and well-controlled trial (which may be single-arm) accompanied by robust confirmatory evidence, which may include appropriately selected external controls or natural history studies [9].

Comparison of Key Pathways

Table: Comparative Analysis of FDA Drug Development Pathways

| Pathway Feature | Accelerated Approval | Plausible Mechanism Pathway | Rare Disease Evidence Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence Standard | Surrogate endpoint reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit | Five core elements demonstrating biological targeting and clinical improvement | One adequate well-controlled trial plus confirmatory evidence |

| Postmarket Requirements | Confirmatory trial required | RWE collection for efficacy preservation, safety signals, and off-target effects | Not specified in available documents |

| Population Focus | Serious conditions with unmet need | Ultra-rare diseases, initially fatal or severely disabling childhood conditions | Rare diseases with known genetic defects (<1,000 U.S. patients) |

| Trial Design Flexibility | Traditional trial designs | Successive single-patient demonstrations | Single-arm trials with external controls accepted |

| Statistical Evidence Level | Standard statistical thresholds | Clinical data strong enough to exclude regression to the mean | "Robust data" providing strong confirmatory evidence |

Recent FDA Guidance Documents for Drug Development

Clinical Trial Design and Conduct

- Innovative Designs for Clinical Trials of Cellular and Gene Therapy Products in Small Populations (September 2025): This draft guidance provides recommendations for planning, designing, conducting, and analyzing trials for cell and gene therapy products in rare diseases [12]. It describes considerations for using various trial designs and endpoints to generate clinical evidence supporting product licensure when patient populations are limited [12].

- Conducting Clinical Trials With Decentralized Elements (Final, September 2024): This guidance offers recommendations for implementing decentralized elements in clinical trials, which can facilitate patient recruitment and retention in rare disease studies [13].

- E20 Adaptive Designs for Clinical Trials (Draft, September 2025): This ICH guidance addresses the use of adaptive designs that may modify trial specifications based on accumulating data while maintaining trial integrity and validity [13].

Gene Therapy and Rare Disease Development

- Expedited Programs for Regenerative Medicine Therapies for Serious Conditions (Draft, September 2025): This guidance outlines expedited programs available for regenerative medicine therapies, including those for rare diseases [14].

- Accelerated Approval of Human Gene Therapy Products for Rare Diseases (Planned 2025 Guidance): This carried-over guidance from 2024 is expected to provide specific recommendations for obtaining accelerated approval for gene therapies targeting rare conditions [15].

- Postapproval Methods to Capture Safety and Efficacy Data for Cell and Gene Therapy Products (Draft, September 2025): This guidance discusses methods for collecting postapproval data, particularly relevant for products approved under novel pathways like the Plausible Mechanism Pathway [14].

Analytical and Computational Approaches

- Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence To Support Regulatory Decision-Making (Draft, January 2025): This guidance addresses the use of AI in regulatory decision-making for drug and biological products [13].

- M15 General Principles for Model-Informed Drug Development (Draft, December 2024): This ICH guidance provides principles for using quantitative models in drug development to support regulatory decision-making [13].

- Real-World Data: Assessing Electronic Health Records and Medical Claims Data (Final, July 2024): This guidance supports the use of real-world data in regulatory decision-making, particularly relevant for postmarket evidence generation [13].

Table: Recent FDA Guidance Documents Relevant to Drug CER Research

| Guidance Document Title | Issue Date | Status | CER Research Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovative Designs for Clinical Trials of Cellular and Gene Therapy Products in Small Populations | 09/2025 | Draft | Alternative trial designs for limited populations |

| Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence To Support Regulatory Decision-Making | 01/2025 | Draft | AI applications in regulatory science |

| Patient-Focused Drug Development: Selecting, Developing, or Modifying Fit-for-Purpose Clinical Outcome Assessments | 10/2025 | Final | Patient-centered endpoint development |

| Real-World Data: Assessing Electronic Health Records and Medical Claims Data | 07/2024 | Final | RWD assessment for regulatory decisions |

| Integrating Randomized Controlled Trials for Drug and Biological Products Into Routine Clinical Practice | 09/2024 | Draft | Hybrid trial designs incorporating real-world evidence |

| Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Human Radiolabeled Mass Balance Studies | 07/2024 | Final | Drug disposition and metabolism studies |

| M14 General Principles on Plan, Design, and Analysis of Pharmacoepidemiological Studies That Utilize Real-World Data | 07/2024 | Draft | RWE study design methodologies |

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Framework for Plausible Mechanism Pathway Applications

The Plausible Mechanism Pathway requires specific methodological approaches to establish product effectiveness [9] [10]. The following workflow outlines key experimental components:

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Targeted Therapy Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in CER Research | Regulatory Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Components (CRISPR-Cas systems, base editors) | Precise modification of disease-associated genetic targets | Demonstration of target engagement for Plausible Mechanism Pathway |

| Animal Disease Models | Preliminary efficacy and safety assessment | Limited use; FDA encourages non-animal models where possible |

| Non-Animal Model Systems (organoids, microphysiological systems) | Target validation and therapeutic screening | Alternative to animal studies per FDA's updated stance |

| Molecular Diagnostic Assays | Patient selection and molecular abnormality confirmation | Eligibility determination for targeted therapies |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Target engagement measurement and pharmacodynamic assessment | Confirmatory evidence for biological activity |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms | Comprehensive molecular characterization and off-target effect assessment | Safety evaluation and molecular abnormality identification |

| Flow Cytometry Panels | Cellular phenotype and immune cell profiling | Cellular abnormality characterization and product potency assessment |

Natural History Study Methodology

Natural history studies form a critical evidence component for rare disease therapeutic development, particularly under the Plausible Mechanism Pathway and RDEP [9]. A robust natural history study should include:

- Prospective Data Collection: Standardized collection of clinical, patient-reported, and biomarker data at regular intervals in untreated patients

- Comprehensive Phenotyping: Detailed characterization of disease manifestations, progression patterns, and variability

- Biomarker Correlations: Association between molecular measures and clinical outcomes

- Endpoint Validation: Development of clinically meaningful endpoints for interventional trials

- Statistical Considerations: Appropriate handling of missing data, patient heterogeneity, and disease trajectory modeling

Regulatory Strategy and CER Research Questions

Pathway Selection Framework

Choosing the appropriate regulatory pathway requires systematic assessment of product and disease characteristics. Key considerations include:

- Population Size and Distribution: The Plausible Mechanism Pathway and RDEP are specifically designed for very small populations (under 1,000 U.S. patients) where traditional trials are infeasible [9]

- Understanding of Disease Biology: The Plausible Mechanism Pathway requires a known and specific molecular abnormality with direct causal relationship to disease [9] [10]

- Endpoint Selection and Validation: Accelerated Approval requires surrogate endpoints reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit, while traditional approval requires direct clinical benefit demonstration [11]

- Manufacturing Considerations: Bespoke therapies under the Plausible Mechanism Pathway must demonstrate consistent manufacturing despite product individualization [10]

Formulating CER Research Questions for Regulatory Submissions

Well-designed CER research questions should align with pathway-specific evidence requirements:

- For Plausible Mechanism Pathway: "Does successive application of bespoke therapies targeting distinct molecular abnormalities in the same disease class demonstrate consistent target engagement and clinical improvement across multiple patients?" [9] [10]

- For Accelerated Approval: "To what extent does the proposed surrogate endpoint correlate with long-term clinical outcomes in the target population, and what level of surrogate validation exists?" [11]

- For RDEP Applications: "Can a single-arm trial with carefully matched historical controls and comprehensive natural history data provide substantial evidence of effectiveness for a genetic disorder affecting <1,000 U.S. patients?" [9]

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

FDA's regulatory science continues evolving, with several notable developments impacting CER research:

- Real-World Evidence Integration: Recent guidances support using RWE for regulatory decisions, particularly in postmarket settings [13]

- Artificial Intelligence Applications: FDA is developing frameworks for AI/ML in drug development and regulatory decision-making [13]

- Complex Innovative Trial Designs: Adaptive, basket, and platform trials are increasingly accepted for targeted therapies and rare diseases [13] [12]

- Patient-Focused Endpoint Development: Recent guidances emphasize incorporating patient experience into endpoint selection and modification [13]

These developments highlight the growing flexibility in FDA's approach to evidence generation while maintaining rigorous standards for safety and effectiveness demonstration.

Defining the research scope throughout the drug development lifecycle represents a critical strategic exercise that directly impacts a product's ultimate success or failure. The contemporary drug development landscape faces a fundamental paradox: despite massive increases in research and development expenditure, the number of yearly approvals for new molecular entities has remained stagnant, with 40–50% of development programs being discontinued even in clinical Phase III [16]. This inefficiency underscores the vital importance of precisely scoping research questions and methodology at each development stage to build a compelling evidence portfolio.

Within this context, comparative effectiveness research (CER) has emerged as a crucial paradigm for evaluating and comparing the benefits and harms of alternative healthcare interventions to inform real-world clinical and policy decisions [17]. This technical guide provides a structured framework for formulating key questions for drug CER research across preclinical, clinical, and post-marketing phases, enabling researchers to establish a scientifically valid scope that generates meaningful evidence for healthcare decision-makers.

Quantitative Foundations for Research Scoping

Core Quantitative Disciplines in Drug Development

The strategic scoping of drug development research relies heavily upon several interconnected quantitative disciplines. Understanding these foundational approaches is essential for formulating precise research questions.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Disciplines in Drug Development Scoping

| Discipline | Definition | Primary Application in Research Scoping |

|---|---|---|

| PK-PD Modeling | Mathematical approach linking drug concentration over time to the intensity of observed response [16] | Describes complete time course of effect intensity in response to dosing regimens |

| Exposure-Response Modeling | Similar to PK-PD modeling but uses exposure metrics (AUC, Cmax, Css) and any type of response (efficacy, safety) [16] | Bridges preclinical and clinical findings; supports dose selection and trial design |

| Pharmacometrics | Scientific discipline using mathematical models based on biology, pharmacology, physiology for quantifying drug-patient interactions [16] | Integrates data from various sources; quantitative decision-making across development phases |

| Quantitative Pharmacology | Multidisciplinary approach integrating relationships between diseases, drug characteristics, and individual variability across studies [16] | Moves away from study-centric approach to continuous quantitative integration |

| Model-Based Drug Development (MBDD) | Paradigm promoting modeling as both instrument and aim of drug development [16] | Formal summary of all available information; full utilization throughout development |

The Model-Based Drug Development Framework

Model-based drug development represents a fundamental mindset shift in which models constitute both the instruments and aims of drug development efforts [16]. Unlike traditional approaches, MBDD covers the whole spectrum of the drug development process instead of being limited to specific modeling techniques or application areas. This approach uses available data, information, and knowledge to their maximum potential to improve development efficiency, forming an iterative cycle where a well-designed MBDD strategy enhances model quality, which in turn refines the development strategy [16].

In practice, MBDD applies modeling to diverse aspects of drug development, including drug design, target screening, formulation choices, exposure-biomarker response, disease progression, healthcare outcome, patient behavior, and socio-economic impact [16]. Knowledge in these areas is formally summarized and reflected in these models and carried over to subsequent development steps, creating a continuous knowledge base rather than siloed stage-specific data.

Phase-Specific Research Scoping Frameworks

Preclinical Research Scoping

Key Scoping Questions for Preclinical Research

The preclinical phase requires scoping research questions that effectively bridge from discovery to first-in-human studies. Critical questions include:

- What are the fundamental mechanisms of action and how do they modulate disease pathways?

- What pharmacokinetic properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) demonstrate adequate exposure at the target site?

- What efficacy biomarkers correlate with target engagement and disease modification?

- What safety margins exist between efficacious and toxic exposures across relevant species?

- How does the candidate compound compare to existing standard of care treatments in predictive models?

Antitarget Assessment and Safety Profiling

A crucial aspect of preclinical scoping involves assessing interactions with "antitargets" – human proteins associated with adverse drug reactions that should not interact with drugs [18]. Quantitative and qualitative structure-activity relationship models ((Q)SAR) represent valuable tools for predicting these interactions, with studies showing that qualitative SAR models demonstrate higher balanced accuracy (0.80-0.81) than quantitative QSAR models (0.73-0.76) for predicting Ki and IC50 values of antitarget inhibitors [18].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Preclinical Antitarget Assessment

| Protocol Component | Methodology Description | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Data Set Curation | Extract structures and experimental Ki/IC50 values from databases (e.g., ChEMBL); transform to pIC50 = -log10(IC50(M)) and pKi = -log10(Ki(M)); use median values for compounds with multiple measurements [18] | Standardized data sets with >100 compounds per antitarget |

| Model Creation | Use GUSAR software with QNA and MNA descriptors; apply self-consistent regression; validate via fivefold cross-validation [18] | Validated (Q)SAR models with defined accuracy metrics |

| Applicability Domain Assessment | Determine compounds falling within model applicability domain; higher for SAR models versus test sets [18] | Reliability assessment for specific compound predictions |

Clinical Development Scoping

Quantitative and Systems Pharmacology Framework

The clinical development phase benefits tremendously from a quantitative and systems pharmacology approach, which integrates physiology and pharmacology to accelerate medical research [19]. QSP provides a holistic understanding of interactions between the human body, diseases, and drugs by simultaneously considering receptor-ligand interactions of various cell types, metabolic pathways, signaling networks, and disease biomarkers [19].

A key advantage of QSP is its ability to integrate data and knowledge through both "horizontal" and "vertical" integration. Horizontal integration entails going beyond narrow focus on specific pathways or targets to understand them within broader contexts by simultaneously considering multiple receptors, cell types, metabolic pathways, or signaling networks. Vertical integration involves integrating knowledge across multiple time and space scales, allowing models to capture both short-term dynamics (e.g., hourly variations in plasma glucose) and longer-term outcomes (e.g., HbA1c levels over months to years) [19].

Clinical Trial Scoping with CER Principles

When scoping clinical trials for comparative effectiveness, researchers should design studies that "address critical decisions faced by patients, families, caregivers, clinicians, and the health and healthcare community and for which there is insufficient evidence" [20]. Proposed trials should compare interventions that already have robust evidence of efficacy and are in current use, focusing on practical clinical dilemmas rather than establishing preliminary efficacy [21].

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute recommends that CER trials employ a two-phase funding approach where an initial feasibility phase (up to 18 months, $2 million direct costs) supports study refinement, infrastructure establishment, patient and stakeholder engagement, and feasibility testing of study operations [20]. This is followed by a full-scale study phase (up to five years, $20 million direct costs) contingent on achieving specific milestones from the feasibility phase [21].

Post-Marketing Research Scoping

Proactive Safety Surveillance Scoping

Post-marketing research scoping must address the reality that serious safety issues often emerge only after products are marketed to larger, more diverse populations. Analysis of FDA data reveals that among 219 new molecular entities approved from 1997-2009, 11 experienced safety withdrawal and 30 received boxed warnings by 2016 [22]. Contrary to prevailing hypotheses, neither clinical trial sample sizes nor review time windows were associated with post-marketing boxed warnings or safety withdrawals [22].

However, drugs approved with either a boxed warning or priority review were significantly more likely to experience post-marketing boxed warnings (3.88 and 3.51 times more likely, respectively) [22]. This suggests that post-marketing research scoping should prioritize these higher-risk products for intensified surveillance.

Post-Marketing Clinical Follow-up Framework

Under the European Medical Device Regulation framework – which offers relevant parallels for pharmaceutical post-marketing requirements – manufacturers must establish a Post-Market Clinical Follow-up plan as a continuous process to proactively collect and evaluate clinical data [23]. The clinical evaluation must be updated regularly throughout the product lifecycle, particularly when new post-market surveillance data emerges that could affect the current evaluation or its conclusions [24].

Table 3: Post-Marketing Safety Signal Detection Framework

| Pre-marketing Factor | Association with Post-marketing Safety Events | Implications for Research Scoping |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial Sample Size | No significant association [22] | Larger pre-approval trials alone unlikely to predict safety issues |

| Review Time Windows | No significant association [22] | Regulatory review deadlines not primary factor in missed safety signals |

| Initial Boxed Warning | 3.88x more likely to receive post-marketing boxed warning [22] | Prioritize intensified monitoring for drugs with initial boxed warnings |

| Priority Review Status | 3.51x more likely to receive post-marketing boxed warning [22] | Enhanced surveillance pathways for rapidly approved drugs |

| Therapeutic Category | Varied by specific category [22] | Category-specific risk profiles should inform monitoring intensity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

GUSAR Software: Utilizes quantitative neighborhoods of atoms and multilevel neighborhoods of atoms descriptors for (Q)SAR model creation; employs self-consistent regression for predicting antitarget interactions and compound activity [18].

Physiology-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling Tools: Provide mechanistic insights into complex and novel modalities; estimate drug distribution in remote compartments; accommodate different populations (pediatrics, elderly, impaired renal function) [19].

Ordinary Differential Equation Solvers: Implement sophisticated mathematical models representing mechanistic details of pathophysiology; capture data from multiple scales from molecular to clinical outcomes [19].

ChEMBL Database: Publicly available database providing structures and experimental Ki and IC50 values for compounds tested on inhibition of various targets; essential for creating training sets for (Q)SAR models [18].

Post-Market Surveillance Data Systems: Systems for collecting clinically relevant post-market surveillance data with emphasis on post-market clinical follow-up; crucial for updating clinical evaluations [24].

Healthcare Administrative Databases: Sources for real-world data on comparative effectiveness and safety of pharmaceutical drugs; particularly valuable for assessing outcomes in population subgroups underrepresented in clinical trials [17].

Integrated Scoping Framework for Drug CER

Cross-Phase Research Question Alignment

Effective research scoping requires alignment of questions across all development phases to build a coherent evidence portfolio for comparative effectiveness. The following diagram illustrates the integration of CER principles throughout the drug development lifecycle:

Stakeholder Engagement in Research Scoping

Meaningful patient and stakeholder engagement represents an essential component of effective research scoping throughout development. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute's "Foundational Expectations for Partnerships in Research" provides a systematic framework for this engagement, emphasizing multiple approaches along a continuum from input to shared leadership [20] [25]. This engagement is particularly crucial during the feasibility phase of CER trials to ensure that research questions address genuine decisional dilemmas faced by patients and clinicians [21].

Defining research scope from preclinical to post-marketing phases requires a systematic, integrated approach that embraces model-based development frameworks, proactively addresses comparative effectiveness questions, and engages relevant stakeholders throughout the process. By implementing the structured scoping frameworks outlined in this technical guide, drug development professionals can formulate precise research questions that generate meaningful evidence for healthcare decision-makers, ultimately improving the efficiency and success rate of drug development programs. The beneficiaries of this disciplined approach to research scoping will ultimately be the patients in need of safe, effective, and properly targeted therapies.

Identifying Critical Stakeholders and Information Needs

Identifying critical stakeholders and their information needs is not an administrative formality but a foundational scientific activity in drug comparative effectiveness research (CER). It ensures that the research addresses questions that are not only clinically relevant but also meaningful to the end-users of the evidence: patients, clinicians, and healthcare systems. CER is fundamentally defined by its purpose to "assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy-makers to make informed decisions" [26]. A well-formulated CER question thus rests on a precise understanding of which stakeholders are critical and what evidence they require to make those decisions. This guide provides a technical roadmap for researchers to systematically integrate this stakeholder analysis into the earliest phases of drug CER study design.

Defining and Identifying Critical Stakeholders in Drug CER

A Standardized Definition and Categorization

In the context of drug CER, a stakeholder is defined as "Individuals, organizations or communities that have a direct interest in the process and outcomes of a project, research or policy endeavor" [26]. This definition emphasizes the vested interest these groups have in the research findings and their application.

Stakeholder engagement is the iterative process of actively soliciting their knowledge and values to create a shared understanding and enable relevant, transparent decisions [26]. For drug development professionals, moving beyond a simple list to a categorized and prioritized inventory is crucial. The following table synthesizes key stakeholder groups and their primary CER interests.

Table 1: Key Stakeholder Groups and Their Core Interests in Drug CER

| Stakeholder Group | Typical CER Interests & Information Needs |

|---|---|

| Patients & Caregivers | Outcomes that matter to daily life (quality of life, symptoms, function); treatment side effects; out-of-pocket costs; understanding of uncertain or negative results [27] [28] [29]. |

| Clinicians | Comparative safety and efficacy in real-world patients; evidence for specific subpopulations; practical implementation of treatments; impact on clinical workflows [27] [26]. |

| Payers & Policymakers | Value relative to existing standards of care; cost-effectiveness; budget impact; generalizability of findings to broader populations [26] [30]. |

| Pharmaceutical Industry | Evidence for product differentiation; value proposition; regulatory and reimbursement requirements; impact on innovation incentives [26] [31]. |

| Research Funders | Relevance of research to address evidence gaps; methodological rigor; potential for findings to be implemented and improve care [27]. |

| 5-Deoxystrigol | 5-Deoxystrigol, CAS:151716-18-6, MF:C19H22O5, MW:330.4 g/mol |

| Quinovic acid | Quinovic acid, CAS:465-74-7, MF:C30H46O5, MW:486.7 g/mol |

Methodological Protocol: The Stakeholder Identification and Analysis Process

A rigorous, multi-step approach ensures no critical perspective is overlooked. The following protocol, adapted from project management and CER-specific literature, provides a detailed methodology [26] [32].

Protocol: Five-Step Stakeholder Analysis

- Stakeholder Identification: Brainstorm a comprehensive list of all potential individuals, groups, and organizations affected by the drug or the CER question. Use techniques like snowball sampling, where identified stakeholders suggest others.

- Stakeholder Mapping and Categorization: Plot stakeholders on an influence/interest matrix. This visual tool helps categorize them as:

- High Power, High Interest: Key players who require close engagement (e.g., primary funders, regulatory bodies).

- High Power, Low Interest: Groups that need to be kept satisfied (e.g., senior organizational leadership).

- Low Power, High Interest: Groups to keep informed (e.g., patient advocacy groups, specific clinician societies).

- Low Power, Low Interest: Groups to monitor with minimal effort.

- Requirements Analysis: For each key stakeholder group, document their specific derived requirements—both communicated and uncommunicated. This goes beyond technical specs to include needs for communication frequency, format, and involvement in the research process [32].

- Interrelationship Analysis: Map the interfaces and relationships between different stakeholder groups. Understanding potential coalitions, conflicts, or overlaps of interest is critical for managing the engagement process effectively.

- Strategy Development and Monitoring: Create a tailored communication and engagement plan for each stakeholder group. This plan should be revisited at major project milestones, as stakeholder interests and influence can change throughout the research lifecycle [32].

The diagram below visualizes the iterative workflow for identifying and analyzing stakeholders.

Eliciting and Structuring Information Needs

The Spectrum of Information Needs

Information needs represent the specific evidence gaps that stakeholders seek to fill to make an informed decision. For drug CER, these needs can be thematically organized. Patient needs often center on "awareness-oriented needs," which include understanding the nature of the disease, how to control it, and the details of treatment options and complications [28]. A systematic review of cancer screening information needs further refines this, showing that needs evolve along an event timeline, focusing on risk factors, benefits/harms of interventions, detailed procedures, and result interpretation [33].

Different stakeholders prioritize different information. For instance, while patients highly value information from genetics professionals and healthcare workers, the internet is also a highly utilized source [29]. This underscores the need for CER to produce evidence that is not only robust but also accessible and communicable through various channels.

Methodological Protocol: Qualitative Assessment of Information Needs

To move from assumptions to validated information needs, researchers should employ structured qualitative methodologies.

Protocol: Conducting a Qualitative Needs Assessment

- Study Design: Conventional qualitative content analysis using a descriptive-explorative design.

- Data Collection: In-depth, semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups. Interviews should be conducted in a setting and language preferred by the participant to ensure comfort and candor [28] [29].

- Interview Guide Development: Develop a guide with open-ended questions, such as:

- "Please explain your informational needs when you first began considering this treatment."

- "What information is most important for you when deciding between different medications?"

- "Can you provide an example of a time you felt you lacked the information to make a good health decision?"

- Sampling: Purposive sampling is used to ensure a diversity of perspectives (e.g., patients of different ages, disease stages, clinicians from different specialties). Data collection continues until thematic saturation is achieved, typically after 10-15 interviews [28].

- Data Analysis: Interviews are audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed systematically.

- The text is divided into meaning units (words, sentences, or paragraphs related by content).

- Meaning units are condensed while preserving the core concept.

- Condensed units are coded.

- Codes are grouped into sub-categories and then abstracted into categories representing the main informational themes [28].

- Trustworthiness: Techniques like peer checking among researchers and member checking (where findings are validated with participants) enhance the credibility and confirmability of the results [28].

The quantitative data from a systematic review of cancer screening information needs demonstrates the prevalence of specific topics, providing a model for how drug CER needs can be categorized.

Table 2: Categorized Information Needs from a Systematic Review of Cancer Screening (Model for Drug CER) [33]

| Theme (by Event Timeline) | Specific Information Needs | Associated Factors for Information-Seeking |

|---|---|---|

| Background & Importance | Disease risk factors; signs and symptoms; importance of early detection. | Passive Attention: Driven by demographic factors (age, education) and fear of the disease. |

| Benefits, Harms & Decision-Making | Comparative benefits and harms of available options; what to expect during and after. | Active Searching: Primarily triggered by a lack of information or a specific decision point. |

| Procedural Details | The detailed screening/treatment process; preparation required; duration. | Information Channel Preference: Interpersonal (clinicians), traditional media, or internet-based. |

| Results & Follow-up | How and when results are provided; interpretation of results; next steps. | Editorial Tone Preference: Desire for clear, understandable, non-judgmental language. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Stakeholder Engagement

Executing a rigorous stakeholder and information needs analysis requires specific methodological "reagents." The following table details these essential tools and their functions for the research team.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Stakeholder and Needs Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the CER Formulation Process |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder Interview Guide | A semi-structured protocol to ensure consistent, open-ended elicitation of needs and expectations across diverse stakeholders. |

| Influence/Interest Matrix | A 2x2 grid used as a visual mapping tool to categorize and prioritize stakeholders based on their relative power and interest in the CER project. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo) | Software designed to manage, code, and analyze non-numerical data from interviews and focus groups, aiding in the identification of themes and categories. |

| Stakeholder Engagement Plan | A living document that outlines tailored communication strategies, frequency of engagement, and responsible parties for each key stakeholder group. |

| Informed Consent Forms | Ethical and regulatory documents ensuring participants understand the study's purpose, the use of their data, and their rights, particularly crucial when engaging patients. |

| CER Priority-Setting Framework (e.g., from CANCERGEN) | A structured process, potentially involving an External Stakeholder Advisory Group (ESAG), to formally prioritize CER topics and study designs based on stakeholder input [26]. |

| Epitulipinolide diepoxide | Epitulipinolide diepoxide, CAS:39815-40-2, MF:C17H22O6, MW:322.4 g/mol |

| Acetylcephalotaxine | Acetylcephalotaxine, CAS:24274-60-0, MF:C20H23NO5, MW:357.4 g/mol |

Integrating Stakeholder Input into CER Question Formulation

The ultimate output of this analytical process is a sharply defined, patient-centered CER question. The gathered data on stakeholder-specific information needs directly informs the PICOT (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Time) framework:

- Population: Defined by stakeholder-identified subpopulations of interest (e.g., by age, comorbidities, genetic markers).

- Intervention & Comparator: Chosen based on the clinical dilemmas most frequently cited by clinicians and patients.

- Outcomes: Centered on the outcomes that matter most to patients and caregivers, such as quality of life, functional status, and symptom burden, rather than solely on biomedical biomarkers [27].

- Time: Informed by the time horizons relevant to decision-making, such as short-term side effects versus long-term survival or functional decline.

This integration ensures the resulting CER study is relevant, practical, and has a clear pathway to implementation, ultimately fulfilling the core mission of CER: to provide useful, trustworthy evidence to those who need it most [27].

Establishing the Foundation for Patient-Centered Outcomes

Comparative clinical effectiveness research (CER) is fundamental to understanding which healthcare options work best for specific patient populations. When applied to drug development, patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) ensures that the evidence generated addresses the questions and outcomes that matter most to patients and those who care for them. The core objective is to provide patients, clinicians, and other stakeholders with the evidence needed to make better-informed health decisions [34]. This guide details the foundational elements—from conceptual frameworks and methodological rigor to practical implementation—required to formulate key questions and conduct robust, patient-centered drug CER.

Foundational Principles of Patient-Centered CER

Patient-centered CER, as championed by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), is defined by several core principles. It directly compares two or more healthcare options, generating evidence about any differences in potential benefits or harms [34]. Crucially, it emphasizes the engagement of patients, caregivers, and the broader healthcare community as equitable partners throughout the entire research process [35]. These individuals leverage their lived experience to make the research more relevant, useful, and patient-centered. The ultimate goal is to bridge the gap between research and practice, ensuring findings are disseminated and implemented to improve care delivery and patient outcomes [35].

Methodological Frameworks for Drug CER

Formulating the Core Research Question

A well-defined research question is the cornerstone of any CER study. For drug-related CER, the question must be comparative, patient-centered, and actionable. The PIO (Population, Intervention, Outcome) framework is a standard starting point, expanded to include the key comparator.

- Population: Precisely define the patient population, including disease characteristics, severity, comorbidities, and prior treatments. Consider subgroups that may experience differential benefits or harms.

- Intervention: Specify the drug therapy, including dosage, administration route, and treatment duration.

- Comparator: Define the alternative against which the intervention is being compared. This could be another active drug, a different dosage of the same drug, a placebo, or non-drug therapy.

- Outcomes: Identify the outcomes that matter to patients. These typically go beyond traditional clinical endpoints (e.g., biomarker levels) to include patient-reported outcomes (PROs) like quality of life, symptom burden, functional status, and treatment burden.

The SPIRIT 2025 Framework for Protocol Development

A complete, transparent protocol is critical for the planning, conduct, and reporting of randomised trials, which are often the source of CER evidence. The updated SPIRIT 2025 statement provides an evidence-based checklist of 34 minimum items to address in a trial protocol, reflecting methodological advances and a greater emphasis on open science and patient involvement [36]. Key updates relevant to drug CER include:

- Item 5 (Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan): Guidance on where the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan can be accessed, promoting transparency [36].

- Item 6 (Data Sharing): Details on where and how individual de-identified participant data, statistical code, and other materials will be accessible [36].

- Item 11 (Patient and Public Involvement): A new, critical item requiring details on how patients and the public will be involved in the trial's design, conduct, and reporting [36]. This formalizes the principle of patient-centeredness within the research protocol.

Adherence to SPIRIT 2025 enhances the transparency and completeness of trial protocols, benefiting investigators, trial participants, funders, and journals [36].

Visualizing the Patient-Centered CER Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative workflow for establishing patient-centered outcomes in drug research, highlighting key stages from stakeholder engagement to evidence dissemination.

Current Priorities and Experimental Protocols in Drug CER

Landscape of Active CER Research

PCORI's recent funding announcements highlight active priority areas in drug CER, which serve as practical examples of the framework in action. These studies often compare drug therapies to other interventions or evaluate different strategies for using medications [34].

Table 1: Examples of Recent Patient-Centered Drug CER Studies

| Health Focus | Comparative Interventions | Patient-Centered Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Infections [34] | Commonly prescribed antibiotics vs. placebo | Resolution of acute ear and sinus infections |

| Pediatric & Adult Weight Management [34] | Different intensities of behavioral/lifestyle treatments paired with obesity medication | Effective and sustainable weight loss |

| Chronic Low Back Pain [34] | Drug therapies vs. non-drug therapies (e.g., physical therapy) | Pain reduction and improved function |

| Severe Aortic Stenosis [34] | Surgical vs. transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Procedure success, recovery time, and quality of life |

Detailed Protocol for a CER Trial on Pediatric Antibiotics

The following workflow details the methodology for a CER study comparing antibiotics to placebo for acute otitis media, incorporating SPIRIT 2025 and patient-centered principles.

Protocol Title: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial Comparing Amoxicillin-Clavulanate to Placebo for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children.

1. Background & Rationale: Despite the high prevalence of antibiotic prescriptions for pediatric acute otitis media (AOM), evidence on the balance of benefits and harms for uncomplicated cases is contested. This study aims to provide clear, comparative evidence on whether antibiotics significantly improve patient-centered outcomes compared to supportive care alone.

2. Objectives:

- Primary Objective: To compare the effect of amoxicillin-clavulanate versus placebo on the duration of significant ear pain, as reported by parents/caregivers.

- Secondary Objectives: To compare the rates of treatment failure, use of rescue analgesics, overall symptom burden, and occurrence of adverse events (e.g., diarrhea, rash).

3. Methods:

- Trial Design: Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

- Participants (P): Children aged 6-12 years with a clinical diagnosis of uncomplicated AOM.

- Intervention (I): Oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (dose based on weight) for 7 days.

- Comparator (C): Matching oral placebo for 7 days.

- Outcomes (O):

- Primary Outcome: Time from randomization to resolution of significant ear pain, measured twice daily via a validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) diary completed by parents.

- Secondary Outcomes:

- Proportion of participants requiring rescue medication within 72 hours.

- Overall symptom severity score (AOM-SOS) over days 1-7.

- Incidence of treatment-related adverse events.

- Rate of disease recurrence within 30 days.

4. Patient and Public Involvement (SPIRIT Item 11): A parent advisory panel was involved in the final selection of the primary outcome measure and the design of the patient-facing materials and diary to ensure they are clear and feasible for use in a stressful home environment.

5. Data Analysis: A time-to-event analysis (Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards model) will be used for the primary outcome. The statistical analysis plan (SAP) was finalized before database lock and is publicly available.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CER

Successful execution of patient-centered CER relies on a suite of methodological "reagents" and tools. The following table details key resources for ensuring methodological rigor, patient engagement, and data integrity.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Patient-Centered CER

| Tool / Resource | Function in CER | Relevance to Patient-Centeredness |

|---|---|---|

| SPIRIT 2025 Checklist [36] | Provides a structured framework for drafting a complete and transparent trial protocol. | Includes a specific item (Item 11) mandating the description of patient and public involvement in design, conduct, and reporting. |

| PCORI Methodology Standards | A comprehensive set of methodological standards for conducting rigorous, patient-centered CER. | Guides researchers on how to incorporate patient perspectives in design and ensure studies address outcomes important to patients. |

| Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Measures | Validated instruments (e.g., diaries, questionnaires) to directly capture the patient's experience of their health. | Moves beyond clinical biomarkers to measure what matters most to patients, such as symptom burden and quality of life. |

| Structured Data Sharing Platforms | Repositories and systems for making de-identified participant data and analytical code accessible. | Promotes transparency, reproducibility, and allows for further research by other scientists, maximizing the value of patient participation. |

| WebAIM Contrast Checker [37] [38] | Tool to verify color contrast ratios in patient-facing digital materials (e.g., ePRO apps, consent forms). | Ensures accessibility for users with low vision or color blindness, aligning with inclusivity principles. Meets WCAG AA standards (4.5:1 for normal text) [37]. |

| Hypocrellin A | Hypocrellin A|CAS 77029-83-5|For Research Use | Hypocrellin A is a natural perylenequinone photosensitizer for cancer PDT, antiviral, and antimicrobial research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| COMC-6 | 2-Crotonyloxymethyl-2-cyclohexenone|Antitumor Research | 2-Crotonyloxymethyl-2-cyclohexenone is a cytotoxic compound for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or personal use. |

Implementation and Future Directions

Establishing a foundation for patient-centered outcomes is an active process that extends beyond the research study's conclusion. The ultimate value of CER is realized when evidence is implemented into clinical practice. PCORI's Health Systems Implementation Initiative (HSII) is an example of this, funding projects that accelerate the uptake of practice-changing findings into care delivery settings [34]. Future directions in the field are being shaped by several key trends, including a focus on improving enrollment of underrepresented study populations to ensure equity, leveraging artificial intelligence for more efficient data management and analysis, and prioritizing complete data transparency between sponsors and contract research organizations (CROs) to improve trial quality and trust [39]. By adhering to rigorous methodologies, engaging patients as authentic partners, and embracing evolving standards and technologies, researchers can consistently generate drug CER evidence that is not only scientifically sound but also meaningful and useful for real-world decision-making.

From Theory to Practice: Designing and Implementing Robust CER Studies

The Clinical Evaluation Plan (CEP) serves as the foundational roadmap for generating the clinical evidence required to demonstrate a drug's safety and efficacy within the European Union's regulatory framework. More than just regulatory paperwork, a well-constructed CEP is a strategic document that directs a systematic and planned process to continuously generate, collect, analyze, and assess the clinical data pertaining to a device in order to verify its safety and performance, including clinical benefits, when used as intended [23]. For drug developers, the CEP establishes the rationale and methodology for the entire clinical evaluation process, ensuring that the subsequent Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) provides sufficient, robust evidence for market approval under the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) [24] [40].

The development of a CEP must be framed within the broader context of formulating precise research questions that will guide evidence generation. A "fail fast" approach in drug discovery emphasizes identifying molecules that lack desired efficacy, safety, or performance characteristics early, saving significant time and resources [41]. Similarly, a rigorously developed CEP helps prevent "fail later" situations by addressing potential formulation, manufacturing, and clinical evidence challenges during the planning phase rather than during regulatory review [41]. This proactive approach is particularly crucial for complex biologic drugs, where issues such as aggregation, degradation, and three-dimensional structure stability can significantly impact biological activity and must be carefully considered during evaluation planning [41].

Formulating Key Research Questions for Drug CER

The foundation of a successful CER protocol lies in formulating rigorous research questions that will direct the evidence generation strategy. The PICO framework (Patient/population; Intervention; Comparison; Outcome) provides a structured approach to ensure research questions encompass all relevant components [42] [43]. For drug development, this framework can be adapted to ensure the CEP addresses all critical aspects of clinical evaluation.

PICO Component Specification for Drugs

Table: PICO Framework Adaptation for Drug CER Protocols

| PICO Component | Definition | Drug Development Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Patient/Population | The subjects of interest [42] | Define specific patient groups by age, medical condition, disease severity, contraindications, and previous treatment history [42] [23]. |

| Intervention | The drug formulation and administration being studied [42] | Specify drug type, dosage form, strength, route of administration, dosing frequency, and delivery system. For biologics, include details on structure and stability [41]. |

| Comparison | The alternative against which the intervention is measured [42] | Define appropriate comparators (active drugs, placebo, usual care, sham procedures) and specify their details as closely as the intervention [42]. |

| Outcome | The effects being evaluated [42] | Define primary and secondary outcomes (economic, clinical, humanistic), considering beneficial outcomes and potential harms. Specify outcome measures and assessment timepoints [42] [23]. |

Beyond proper construction, research questions must be capable of producing valuable and achievable results. The FINER criteria (Feasible; Interesting; Novel; Ethical; Relevant) provide a tool for evaluating research questions for practical considerations [42]:

- Feasible: Consider availability of resources including funding, time, institutional support, data accessibility, and required personnel expertise [42].

- Interesting: The question should appeal to both the researcher and the wider scientific community, making the eventual findings more competitive for funding and publication [42].

- Novel: The question should address a clear knowledge gap through a rigorous literature review, either by improving upon previous studies, investigating unknown areas, or purposefully replicating existing work [42].

- Ethical: Researchers must consider ethical implications and engage with appropriate oversight bodies during the early conceptualization phase [42].

- Relevant: The question should have significance to scientific knowledge, clinical practice, and policy decisions [42].

Research Question Formulation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic process for developing research questions within a CER protocol:

Core Components of a Comprehensive CER Protocol

A robust CER protocol must systematically address all regulatory requirements while establishing a clear methodology for evidence generation and assessment. The following components are essential for MDR compliance and demonstrating sufficient clinical evidence.

Strategic Planning and Scope Definition

The initial section of the CEP establishes the foundation for the entire clinical evaluation:

- Device/Drug Intended Purpose: Precisely define the therapeutic indication, target population with clear indications and contraindications, and the intended clinical benefits to patients [23].

- Clinical Claims and Acceptance Criteria: Specify clinical claims relevant to performance, safety, and benefits, along with specific thresholds that will serve as acceptance criteria for determining clinical acceptability [23].

- State of the Art Definition: Establish the current, generally accepted best practices and standards in medical technology and treatment for the condition, which serves as a benchmark for comparing the drug's performance and risk-benefit profile [23].

- Evaluation Strategy: Define the approach for demonstrating compliance with the MDR, which may rely on clinical data pertaining to the drug under evaluation and/or other approaches such as equivalence [23].

Clinical Development Plan

The CEP should outline a clinical development plan that describes the progression from early exploratory investigations to confirmatory studies and post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF), including milestones and acceptance criteria [23]. This plan should explicitly address:

- Data Sources Identification: Specify sources for obtaining relevant clinical data (literature reviews, manufacturer-sponsored clinical studies, post-market surveillance reports, registries, etc.) [24] [23].

- Literature Search Protocol: Detail the methodology for systematic literature reviews, including search strategies, databases, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and quality assessment methods to ensure objective, non-biased review methods [23].

- Equivalence Demonstration (if applicable): For drugs claiming equivalence to an existing product, establish detailed justification and evidence supporting equivalence in clinical, technical, and biological characteristics [23].

- Post-Market Clinical Follow-up (PMCF) Planning: Define the strategy for proactively collecting and evaluating clinical data from the use of the drug after market entry to update the clinical evaluation throughout the device lifecycle [24] [23].

Methodology for Data Identification, Appraisal, and Analysis

The CEP must establish rigorous methodologies for handling clinical data:

- Data Identification Process: Describe systematic approaches for identifying all pertinent data, both favorable and unfavorable, from published literature and manufacturer-held sources [23].

- Data Appraisal Framework: Define criteria for objectively evaluating the scientific validity and relevance of included data, including study design quality, potential biases, and statistical robustness [23].

- Data Analysis Plan: Specify analytical methods for synthesizing evidence across studies, assessing consistency of results, and evaluating the overall body of evidence regarding safety and performance [23].

- Benefit-Risk Assessment Methodology: Establish parameters for determining the acceptability of the benefit-risk ratio, including methods for qualitative and quantitative assessment of clinical safety, residual risks, and side effects [23].

Regulatory Framework and Compliance Requirements

Understanding the regulatory context is essential for developing a compliant CER protocol. The European Medical Device Regulation (MDR 2017/745) imposes specific requirements for clinical evaluations that manufacturers must follow throughout the device lifecycle.

Regulatory Evolution and Current Standards

The MDR introduced significantly stricter requirements compared to the previous Medical Device Directive (MDD), including [23]:

- Mandatory PMCF: Requirement for continuous clinical data collection post-market approval [23].

- Explicit CEP Requirement: Formal requirement for a documented Clinical Evaluation Plan [23].

- Stricter Equivalence Criteria: More rigorous requirements for demonstrating equivalence to existing products [23].

- Sufficient Clinical Evidence: Introduction of the concept of "sufficient clinical evidence," interpreted as "the present result of the qualified assessment which has reached the conclusion that the device is safe and achieves the intended benefits" [23].

Clinical Evaluation Process Workflow

The clinical evaluation follows a defined process from planning through reporting and updating, as shown in the following workflow:

This continuous process requires regular updates to the CER throughout the device lifecycle, particularly when new post-market surveillance (PMS) or PMCF data emerges that could affect the current evaluation or its conclusions [24].

Experimental Protocols and Data Quality Assessment

Robust experimental protocols and rigorous data quality assessment are fundamental to generating valid clinical evidence for the CER.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Drug CER

| Reagent/Material | Function in CER Development | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic Review Software | Facilitates structured literature search, data extraction, and quality assessment of clinical studies | Literature review and data identification phase [23] |

| Data Quality Assessment Framework | Provides systematic approach to evaluate completeness, accuracy, and reliability of clinical data | Appraisal of all relevant clinical data from various sources [44] |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | Enable quantitative synthesis of clinical evidence, meta-analysis, and benefit-risk modeling | Data analysis phase for synthesizing evidence across studies [23] |

| Predictive Modeling Programs | Assist in determining dose frequency, formulation stability, and route of administration | Early development phase for informing clinical trial design [41] |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Provide objective measures of drug activity, safety parameters, and treatment response | Clinical studies for generating supplemental evidence of mechanism [41] |

Data Quality Assessment Framework

For CERs leveraging real-world data or secondary data sources, a comprehensive data quality assessment (DQA) framework is essential. The harmonized DQA model developed through the Electronic Data Methods Forum addresses key dimensions [44]:

- Completeness: Assessment of missing data elements that could impact study validity, with explicit definitions tailored to specific research needs [44].

- Accuracy: Evaluation of data correctness through validation against source documents or through consistency checks across related data elements [44].

- Consistency: Determination of whether data values are consistent across time and between related data elements within the dataset [44].

- Plausibility: Assessment of whether data values are clinically meaningful and within expected ranges for the patient population [44].

- Timeliness: Evaluation of whether data is current and available within the required timeframes for analysis [44].

The DQA process should generate standardized reports such as the Observational Source Characteristics Analysis Report (OSCAR) for summarizing data source characteristics and Generalized Review of OSCAR Unified Checking (GROUCH) for identifying implausible or suspicious data patterns [44].

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Strategies to Overcome Common Challenges

Drug developers frequently encounter several challenges when preparing CER protocols:

- Insufficient Clinical Evidence: Provide robust evidence for all populations, indications, and device variants. Gaps in clinical evidence are frequently challenged by notified bodies and may result in non-conformities [23].

- CEP-CER Inconsistency: Adhere to the CEP throughout the evaluation process. Document any necessary deviations thoroughly, as inconsistencies between the CEP and CER often result in non-conformities [23].

- Inadequate Benefit-Risk Analysis: Develop a structured, quantitative approach to benefit-risk assessment that considers both beneficial outcomes and potential harms, using the state of the art as a benchmark [23].

- Poorly Defined Strategy: Ensure the evaluation strategy is thoroughly described in the CEP. An unclear or poorly defined CEP typically leads to frequent updates and revisions throughout the evaluation process [23].

- Data Transparency: Include all relevant data, even unfavorable findings, to maintain scientific credibility and regulatory trust [23].

Best Practices for MDR-Compliant CER Protocols

- Early Engagement: Engage with qualified experts and notified bodies during the protocol development phase to identify potential issues before implementation [41].

- Systematic Literature Review: Employ objective, non-biased systematic review methods with predefined search protocols and inclusion criteria [23].

- Alignment with Device Documentation: Ensure consistency between the CEP/CER and the device's technical documentation, including the risk management file and instructions for use [23].

- Qualified Personnel: Ensure that individuals conducting the clinical evaluation possess the necessary expertise in relevant clinical specialties, research methodology, and regulatory requirements [23].

- Proactive Planning for Updates: Establish a plan for regular CER updates based on predetermined schedules and triggers, incorporating PMS and PMCF findings [24] [23].