Propensity Score Methods in Pharmacoepidemiology: A Modern Guide to Confounding Control and Causal Inference

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of propensity score (PS) methods in pharmacoepidemiology, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Propensity Score Methods in Pharmacoepidemiology: A Modern Guide to Confounding Control and Causal Inference

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of propensity score (PS) methods in pharmacoepidemiology, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from defining causal estimands within the potential outcomes framework to implementing key designs like the new-user active comparator design to mitigate biases. The scope extends to practical guidance on methodological execution, including matching, weighting, and the use of high-dimensional propensity scores (hdPS) with machine learning for covariate selection. It also addresses troubleshooting for common challenges such as the 'PSM paradox,' model dependence, and unmeasured confounding, while validating methods through balance assessment and alignment with emerging frameworks like ICH E9(R1) and target trial emulation. The synthesis aims to equip researchers with the knowledge to produce more valid and reliable real-world evidence on drug safety and effectiveness.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Causal Frameworks for Propensity Scores

The Role of Propensity Scores in Addressing Confounding by Indication

Confounding by indication represents a fundamental methodological challenge in pharmacoepidemiology and comparative effectiveness research. This form of confounding arises when the clinical indications for prescribing a particular medication are themselves associated with the study outcome, creating a spurious association between treatment and outcome that does not reflect a causal relationship [1]. In clinical practice, healthcare professionals appropriately prescribe treatments based on patients' prognostic factors, channeling specific medications toward patients with particular characteristics or disease severities [1]. This channeling phenomenon, while clinically appropriate, creates substantial imbalances in baseline prognosis between treated and untreated groups in observational studies, potentially leading to severely biased treatment effect estimates if not adequately addressed.

Propensity score (PS) methods were specifically developed to address such confounding in observational studies by modeling how prognostic factors influence treatment decisions [1]. The propensity score, defined as the conditional probability of receiving treatment given observed covariates, provides a powerful tool for creating balanced comparison groups that mimic the balance achieved in randomized controlled trials [2]. By balancing measured baseline characteristics across treatment groups, propensity score methods help isolate the true effect of the treatment from the confounding influence of the treatment indications [3]. The application of propensity scores has become increasingly sophisticated, with recent advances including machine learning integration, high-dimensional propensity scores, and extensions for complex treatment regimens [4] [5].

Theoretical Foundations of Propensity Score Methods

The Propensity Score Framework

The theoretical foundation of propensity score analysis rests on the potential outcomes framework for causal inference [1]. For each patient, we consider potential outcomes under treatment (Y(1)) and control (Y(0)) conditions. The propensity score, defined as e(X) = P(Z=1|X), where Z indicates treatment assignment and X represents observed covariates, possesses the key property of being a balancing score [1]. This means that conditional on the propensity score, the distribution of observed baseline covariates is independent of treatment assignment: X ⊥ Z | e(X).

For valid causal inference using propensity scores, two critical assumptions must be satisfied. The first is strong ignorability, which requires that all common causes of treatment and outcome are measured and included in the propensity score model [2]. The second is the positivity assumption, which stipulates that every patient has a non-zero probability of receiving either treatment: 0 < P(Z=1|X) < 1 for all X [2]. When these assumptions hold, the propensity score can be used to remove confounding by indicated factors, enabling unbiased estimation of average treatment effects.

Evolution of Propensity Score Applications

Propensity score methods have evolved significantly since their introduction by Rosenbaum and Rubin in 1983 [4]. Initially applied primarily in settings with limited numbers of predefined confounders, these methods have expanded to address the challenges of high-dimensional healthcare databases, which may contain hundreds of potential covariates [1]. This evolution has included the development of automated variable selection algorithms, extensions for time-varying treatments, and incorporation of machine learning techniques for model specification [5].

Table 1: Key Developments in Propensity Score Methodology

| Development | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Dimensional Propensity Score (hdPS) | Automated algorithm to select and prioritize covariates from large healthcare databases | Claims data analysis with numerous potential confounders [1] |

| Generalized Propensity Scores | Extension to categorical and continuous treatments | Comparative effectiveness of multiple treatments [1] |

| Machine Learning Integration | Use of ensemble methods, autoencoders, and other ML approaches for PS estimation | High-dimensional data with complex nonlinear relationships [4] |

| Target Trial Emulation | Framework for designing observational studies that mimic randomized trials | Addressing time-related biases and confounding [6] |

Practical Implementation of Propensity Score Methods

Propensity Score Estimation Protocols

The first step in implementing propensity score methods involves building an appropriate model for treatment assignment. Traditional approaches typically use logistic regression with investigator-specified covariates based on clinical knowledge and literature review [1]. However, in high-dimensional settings such as healthcare claims databases, several advanced approaches have been developed:

High-Dimensional Propensity Score (hdPS) Algorithm: This automated approach identifies and prioritizes covariates from large healthcare databases based on their potential for confounding adjustment [1]. The hdPS algorithm empirically identifies data dimensions (e.g., medication codes, diagnosis codes, procedure codes) and selects covariates based on their prevalence and potential for bias reduction.

Dimensionality Reduction Techniques: Recent methodological advances include the application of principal component analysis (PCA), logistic PCA, and autoencoders for propensity score estimation [4]. In a 2025 cohort study comparing dialysis exposure in heart failure patients, autoencoder-based propensity scores achieved superior covariate balance compared to traditional methods, with only 8 covariates showing standardized mean differences >0.1 versus 20-83 covariates with other methods [4].

Machine Learning Approaches: Ensemble methods, random forests, and regularized regression can accommodate complex nonlinear relationships and interactions without overfitting [7]. These approaches are particularly valuable when the true treatment assignment mechanism is complex or unknown.

Table 2: Comparison of Propensity Score Estimation Methods in a 2025 Cohort Study [4]

| Propensity Score Method | Number of Covariates with SMD>0.1 | Relative Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Autoencoder-based PS | 8 | Best balance |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | 20 | Good balance |

| Logistic PCA | 25 | Moderate balance |

| High-Dimensional Propensity Score (hdPS) | 37 | Limited balance |

| Investigator-specified Covariates | 83 | Poorest balance |

Propensity Score Application Protocols

After estimating propensity scores, researchers must select an appropriate method for incorporating these scores into the analysis. The four primary approaches are:

Propensity Score Matching: This method creates matched sets of treated and untreated subjects with similar propensity scores [7]. The most common implementation is 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement, often with a caliper width (typically 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score) to prevent poor matches [7]. After matching, balance should be assessed using standardized mean differences (target <0.1) and variance ratios.

Propensity Score Weighting: Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) creates a pseudo-population in which treatment assignment is independent of measured covariates [2]. Weights are defined as w = Z/e(X) + (1-Z)/(1-e(X)). Alternative weighting schemes include matching weights and overlap weights, which may improve precision and balance in regions of poor propensity score overlap [1].

Propensity Score Stratification: Subjects are stratified into quantiles (typically 5-10 strata) based on their propensity scores, and treatment effects are estimated within each stratum before pooling [2]. This approach works well when the relationship between propensity score and outcome is approximately constant within strata.

Covariate Adjustment: The propensity score is included directly as a covariate in the outcome regression model [7]. While straightforward to implement, this approach requires correct specification of both the propensity score model and the outcome model.

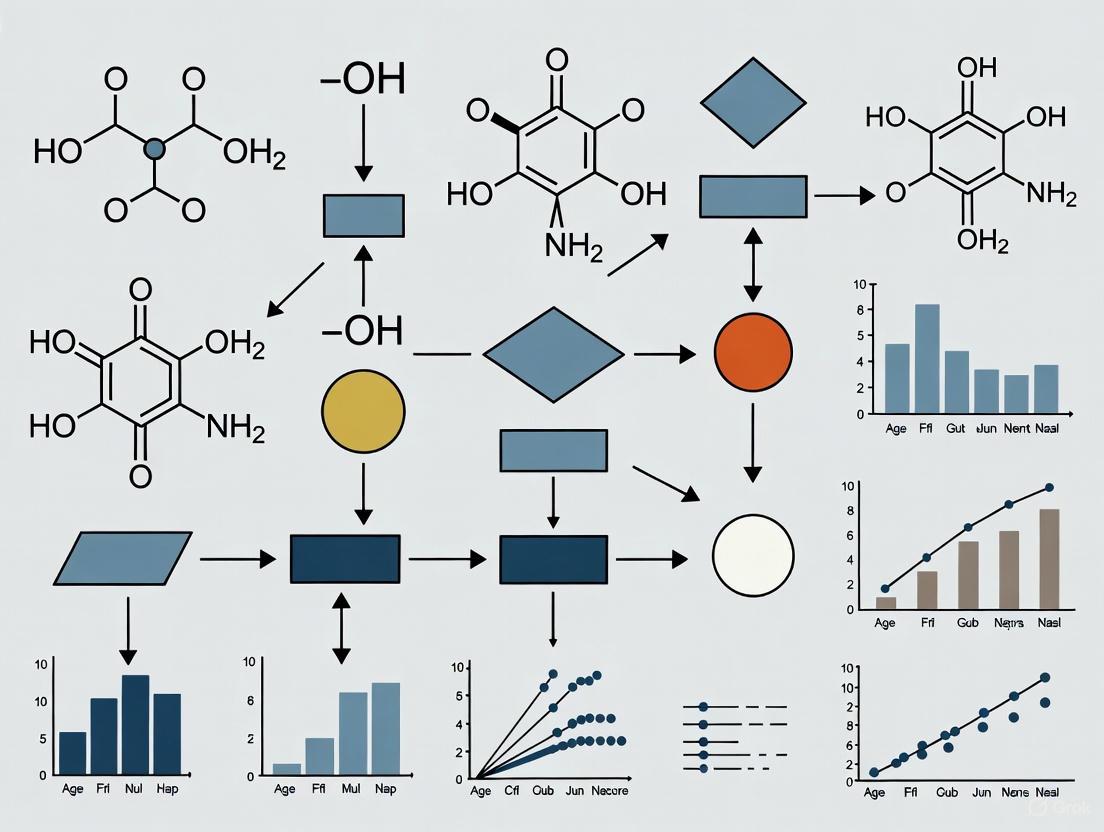

Figure 1: Propensity Score Analysis Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process for implementing propensity score methods, highlighting the iterative balance assessment stage.

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Addressing Complex Biases in Pharmacoepidemiology

Recent applications of propensity score methods have demonstrated their utility in addressing multiple methodological challenges simultaneously. A 2025 study in multiple sclerosis research implemented a high-dimensional propensity score analysis within a nested case-control framework to simultaneously address immortal time bias and residual confounding [6]. This innovative approach combined the design-based control of immortal time bias through the nested case-control design with the confounding control of hdPS, demonstrating a 28% reduction in mortality risk associated with disease-modifying drugs (HR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.62-0.84) [6].

The hdPS algorithm was particularly valuable in this context as it could empirically identify hundreds of potential confounders from healthcare claims data, including diagnostic codes, procedure codes, and medication records [6]. The algorithm prioritizes covariates based on their potential for confounding control, allowing researchers to address residual confounding that might remain after adjustment for predefined covariates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Methodological Tools for Propensity Score Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in PS Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (MatchIt, twang, WeightIt), SAS (PROC PSMATCH), Python (causalinference, psmatching) | Implementation of propensity score estimation and application methods |

| Balance Metrics | Standardized mean differences, variance ratios, Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics | Quantifying covariate balance between treatment groups after PS adjustment |

| High-Dimensional Covariate Algorithms | hdPS, LASSO, Bayesian confounding adjustment | Automated covariate selection in settings with numerous potential confounders |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Random forests, gradient boosting, autoencoders, principal component analysis | Flexible propensity score estimation with minimal model misspecification |

| Sensitivity Analysis Methods | Rosenbaum bounds, E-values, propensity score calibration | Assessing robustness to unmeasured confounding |

| MurA-IN-4 | MurA-IN-4, CAS:318280-69-2, MF:C8H12ClNO3, MW:205.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tetramethyl-d12-ammonium bromide | Tetramethyl-d12-ammonium bromide, CAS:284474-82-4, MF:C4H12BrN, MW:166.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Validation and Sensitivity Analysis Protocols

Assessing Covariate Balance

The critical step in validating any propensity score analysis is assessing whether the method has successfully balanced covariates between treatment groups. The following protocol should be implemented:

Calculate standardized mean differences (SMD) for all covariates before and after propensity score adjustment. The SMD should be ≤0.1 for all important confounders to indicate adequate balance [4].

Examine variance ratios (ratio of variances between treatment groups) for continuous covariates, with ideal values between 0.5 and 2.0.

Visualize balance using Love plots, which display SMDs before and after adjustment, and empirical cumulative distribution function plots for continuous variables.

Assess propensity score distribution overlap using histograms or kernel density plots by treatment group.

In the 2025 dialysis study, the superiority of autoencoder-based propensity scores was demonstrated through superior balance metrics, with only 8 covariates showing SMD>0.1 compared to 20-83 with other methods [4].

Sensitivity Analysis for Unmeasured Confounding

Since propensity scores can only adjust for measured confounders, sensitivity analysis is essential to assess potential residual confounding:

Propensity Score Calibration: This method uses additional information on a subset of patients to correct for unmeasured confounding [1] [8].

External Adjustment: Incorporate estimates of the strength of association between unmeasured confounders and both treatment and outcome from external literature [3].

E-Value Calculations: Quantify the minimum strength of association that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both treatment and outcome to explain away the observed effect [3].

Figure 2: Propensity Score Role in Addressing Confounding by Indication. This causal diagram illustrates how propensity scores (derived from measured covariates) help block backdoor paths created by treatment indications.

Propensity score methods represent a powerful approach for addressing confounding by indication in pharmacoepidemiological studies. When properly implemented, these methods can create balanced comparison groups that approximate the balance achieved in randomized trials, substantially reducing bias in treatment effect estimates [3]. The recent methodological advances in propensity score applications—including high-dimensional propensity scores, machine learning integration, and sophisticated weighting approaches—have enhanced their utility in modern healthcare database studies [4] [5].

Future developments in propensity score methodology will likely focus on improving robustness to model misspecification, enhancing approaches for time-varying treatments, and developing more sophisticated integration with machine learning techniques [1]. Additionally, there is growing interest in transparent reporting standards and sensitivity analysis frameworks that appropriately communicate the strength of evidence from propensity score analyses [3]. As these methods continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly important role in generating valid real-world evidence about treatment benefits and harms in clinical practice.

The Potential Outcomes Framework and Assumptions for Causal Inference

The Potential Outcomes Framework (POF), also known as the Rubin Causal Model (RCM), provides a formal mathematical foundation for defining and estimating causal effects. In the context of pharmacoepidemiological studies, which often rely on observational data from sources like health claims databases, this framework is indispensable for estimating the causal effects of drug exposures on patient outcomes while accounting for confounding [9] [10]. The framework augments the observed data by considering the outcomes that would occur under all possible treatment states, thus enabling a rigorous articulation of the assumptions required for causal inference.

Core Concepts of the Potential Outcomes Framework

Potential Outcomes and Causal Estimands

Consider a binary treatment (Z) (e.g., (Z=1) for drug exposure and (Z=0) for control). The potential outcome framework augments the joint distribution of ((Z,Y)) by introducing two random variables, ((Y(1), Y(0))), where:

- (Y(1)) is the outcome if the unit receives treatment.

- (Y(0)) is the outcome if the unit does not receive treatment [9].

The observed outcome (Y) is then defined as: [ Y = \begin{cases} Y(1) & \text{if } Z = 1 \ Y(0) & \text{if } Z = 0 \end{cases} ] or, more compactly, (Y^{\text{obs}} = Z \cdot Y(1) + (1-Z) \cdot Y(0)) [9]. The key problem of causal inference is that for any individual unit, only one of these potential outcomes is observed; the other is counterfactual [9] [10].

Within this framework, several causal estimands can be defined. The table below summarizes the most common ones.

Table 1: Key Causal Estimands in the Potential Outcomes Framework

| Estimand | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Treatment Effect (ITE) | (\taui = Yi(1) - Y_i(0)) | The causal effect for a single unit (i) [9]. |

| Average Treatment Effect (ATE) | (\mathrm{E}[Y(1) - Y(0)]) | The expected effect of moving an entire population from control to treatment [9] [10]. |

| Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) | (\mathrm{E}[Y(1)-Y(0)|Z=1]) | The average effect for those who actually received the treatment [10]. |

In pharmacoepidemiology, the choice between ATE and ATT depends on the research question. The ATE is often relevant for policy decisions (e.g., what is the effect of introducing a new drug to the entire population?), whereas the ATT is useful for understanding the effect on patients who typically receive a particular treatment [10].

The Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference

The core challenge is that the ITE (\taui) is fundamentally unobservable because it requires simultaneously observing both (Yi(1)) and (Y_i(0)) for the same unit [9] [10]. Therefore, statistical methods for causal inference must rely on comparisons between groups under assumptions that allow the unobserved potential outcomes to be inferred from the observed data.

Critical Assumptions for Causal Identification

For causal effects to be identified from observed data, certain assumptions must hold. The following diagram illustrates the core structure of the problem and the role of these assumptions.

Diagram 1: Potential Outcomes and Confounding. Y(1) and Y(0) are potential outcomes. Solid lines represent observed relationships, while dashed lines represent unobserved influences. Confounders (X, U) affect both treatment and outcomes.

Unconfoundedness (Ignorability)

This is the most critical assumption for causal inference in observational studies. It states that, conditional on observed covariates (X), the treatment assignment (Z) is independent of the potential outcomes [9] [10] [11]: [ (Y(1), Y(0)) \perp ! ! ! \perp Z \mid X ] This means that, within strata defined by the covariates (X), the assignment to treatment or control is as good as random [10]. This assumption is also known as the "no unmeasured confounding" assumption. In Diagram 1, this assumption would hold if all common causes of (Z) and (Y) (the confounders) are captured in (X), with no role for (U) [12] [13].

Positivity (Overlap)

This assumption requires that every unit has a positive probability of receiving either treatment, given the covariates [10]: [ 0 < P(Z=1 \mid X) < 1 ] In practice, this means that for all values of the observed covariates (X), there are both treated and untreated units. This ensures that there is a comparable control unit for every treated unit, and vice-versa, allowing for meaningful comparisons.

Consistency

The consistency assumption links the potential outcomes to the observed data. It states that the observed outcome for a unit that received treatment (Z=z) is exactly that unit's potential outcome under (z) [10]: [ \text{If } Z=z, \text{ then } Y^{\text{obs}} = Y(z) ] This implies that the treatment is well-defined and that there is no interference between units (the potential outcome of one unit is not affected by the treatment assignment of other units).

Application in Pharmacoepidemiology: The Role of Propensity Scores

In high-dimensional pharmacoepidemiological studies, directly conditioning on all covariates (X) is often impractical due to the curse of dimensionality. The propensity score, defined as the probability of treatment assignment conditional on observed covariates, (e(X) = P(Z=1|X)), addresses this issue [10] [11]. Rosenbaum and Rubin showed that if treatment assignment is unconfounded given (X), it is also unconfounded given the propensity score (e(X)) [10]: [ (Y(1), Y(0)) \perp ! ! ! \perp Z \mid e(X) ] This allows researchers to adjust for confounding by using the scalar propensity score instead of the high-dimensional vector (X).

Table 2: Common Propensity Score Methods in Pharmacoepidemiology

| Method | Protocol Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Matching (PSM) | Treated subjects are matched to untreated subjects with similar propensity scores. The ATE or ATT is estimated by comparing outcomes between matched groups [10]. | Requires decisions on matching algorithm (e.g., 1:1 nearest-neighbor), caliper width, and with/without replacement. Assess balance of covariates post-matching. |

| Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) | Subjects are weighted by the inverse of their probability of receiving the treatment they actually received. Weights: (1/e(X)) for treated, (1/(1-e(X))) for untreated [10] [11]. | Creates a "pseudo-population" where confounding is eliminated. Can be unstable with extreme weights; truncated or stabilized weights are often used. |

| Stratification (Subclassification) | The sample is divided into strata (e.g., quintiles) based on the propensity score. Treatment effects are estimated within each stratum and then pooled [10]. | Typically, 5 strata remove ~90% of bias from a continuous confounder. Assess balance within strata. |

| Covariate Adjustment | The propensity score is included as a covariate in a regression model for the outcome [10]. | Simple to implement but relies on correct specification of the outcome model. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates a standard protocol for applying propensity score methods in a pharmacoepidemiological study.

Diagram 2: Propensity Score Analysis Workflow. This iterative process ensures confounding is adequately addressed before effect estimation.

Advanced Applications: High-Dimensional Propensity Scores (hdPS)

Pharmacoepidemiological studies using claims data often contain hundreds of potential covariates. The high-dimensional propensity score (hdPS) algorithm is a semi-automated data-driven method to efficiently select and adjust for a large number of covariates from such databases [4]. The protocol involves:

- Identifying Covariate Proxies: Identifying all recorded diagnoses, procedures, and drug prescriptions as potential covariates.

- Prioritizing Covariates: Ranking these covariates by their potential for confounding based on their prevalence and association with the treatment and outcome.

- Score Estimation: Including the top (n) covariates (e.g., 500) in the propensity score model [4] [6].

Recent research has shown that combining hdPS with dimensionality reduction techniques like autoencoders can further improve covariate balance in such high-dimensional settings [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Causal Inference

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Causal Inference Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Healthcare Databases | Provide longitudinal data on drug exposure, patient outcomes, and confounders. | Examples: Claims data (e.g., Optum's Clinformatics Data Mart), electronic health records (EHR). Data quality and completeness are critical [4] [6]. |

| Propensity Score Estimation Algorithms | Model the probability of treatment assignment given covariates. | Logistic regression is standard. Advanced methods: hdPS, machine learning (boosted regression, random forests, autoencoders) for high-dimensional data [4] [10] [11]. |

| Balance Diagnostics | Quantify the similarity of covariate distributions between treated and control groups after PS adjustment. | Primary metric: Standardized Mean Differences (SMD). Target: SMD < 0.1 for all covariates. Visualization: Love plots, overlap plots [4] [10]. |

| Causal Graphical Models | Visually represent assumptions about causal relationships between variables. | Used to identify a sufficient set of confounders and to spot sources of bias like colliders [12] [13]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Frameworks | Quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away an observed effect. | Assesses the robustness of causal conclusions to potential violations of the unconfoundedness assumption [14]. |

| Amethopterin-d3 | Amethopterin-d3, MF:C20H22N8O5, MW:457.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dodecanedioic acid-d20 | Dodecanedioic acid-d20, CAS:89613-32-1, MF:C12H22O4, MW:250.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: A Case Study on Dialysis and Mortality

To illustrate, here is a detailed protocol based on a real pharmacoepidemiological study investigating the association between dialysis and mortality in older heart failure patients [4].

Aim: To estimate the average treatment effect of dialysis on in-hospital mortality. Data Source: Optum's de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database. Design: Retrospective cohort study with propensity score matching.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Cohort Definition:

- Inclusion: Patients with heart failure and advanced chronic kidney disease.

- Exposure: Initiation of dialysis (Z=1) vs. no dialysis (Z=0).

- Outcome: All-cause in-hospital mortality (dichotomous).

- Final Cohort: 485 exposed and 1,455 unexposed after matching.

Propensity Score Estimation:

- Covariates (X): A high-dimensional set of covariates derived from claims data, including demographics, comorbidities, medications, and healthcare utilization.

- Method Comparison: The study compared PS estimated via:

- Investigator-specified covariates: Expert-selected variables.

- hdPS: A data-driven algorithm.

- Dimensionality Reduction Techniques: Principal Component Analysis (PCA), logistic PCA, and autoencoders [4].

Propensity Score Application:

- Matching: 1:1 matching was performed without replacement within a specified caliper.

- Balance Assessment: Covariate balance was assessed using SMDs across all PS methods.

Outcome Analysis:

- Effect Estimation: Hazard ratios for mortality were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models on the matched cohorts.

- Result: Autoencoder-based PS achieved the best covariate balance (only 8 covariates with SMD > 0.1), and hazard ratios for mortality were similar across all PS methods [4].

This case study demonstrates the application of the potential outcomes framework and highlights how advanced PS methods can improve confounding control in real-world research.

In pharmacoepidemiological studies research, which often relies on large, observational healthcare databases, defining the precise causal question is the critical first step before any analysis begins [1]. The causal estimand is a precise description of the causal quantity one seeks to learn from the data, specifying the target population, the treatment contrast of interest, and the outcome [15]. Within the potential outcomes framework, three fundamental estimands are the Sample Average Treatment Effect (SATE), the Sample Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (SATT), and the Population Average Treatment Effect (PATE) [1] [16]. The choice between them hinges on the underlying clinical question and dictates the analytical approach, the interpretation of results, and the scope of inference. Propensity score methods are a primary tool for estimating these estimands from observational data by attempting to mimic the balance achieved in randomized trials [1] [17]. This document outlines the definitions, applications, and estimation protocols for SATE, SATT, and PATE, framed specifically for pharmacoepidemiology research.

Defining the Estimands

Core Definitions and Formulations

The following table summarizes the core definitions and formulations of the three primary estimands.

Table 1: Core Definitions of SATE, SATT, and PATE

| Estimand | Full Name | Definition | Causal Question | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SATE | Sample Average Treatment Effect | SATE = (1/n) * Σ [Y_i(1) - Y_i(0)] for all units i in the study sample [1]. |

What is the average treatment effect for all individuals in our study sample? | Efficacy evaluation within a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or a well-defined observational cohort [16]. |

| SATT | Sample Average Treatment Effect on the Treated | SATT = (1/n_t) * Σ [Y_i(1) - Y_i(0)] for all units i who actually received the treatment in the sample [1]. |

What is the average treatment effect for those individuals who actually received the treatment in our study? | Effectiveness and safety research in pharmacoepidemiology, where inference is for the patients who are prescribed the drug in real-world practice [18] [1]. |

| PATE | Population Average Treatment Effect | PATE = E[Y(1) - Y(0)] for all units in the broader target population [16]. |

What is the average treatment effect for the entire target population of interest? | Guiding broad policy or formulary decisions for a entire patient population (e.g., all patients with a specific condition in a country) [16]. |

These estimands are defined within the potential outcomes framework (or Rubin Causal Model) [1] [15]. For each individual i, there exists a potential outcome under treatment, Y_i(1), and a potential outcome under control, Y_i(0). The individual treatment effect is Ï„_i = Y_i(1) - Y_i(0). The fundamental problem of causal inference is that we can never observe both Y_i(1) and Y_i(0) for the same individual [15]. Therefore, we define average effects, like SATE, SATT, and PATE, over groups of individuals.

Conceptual Relationships and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between the different estimands and the general workflow for defining a causal question.

Estimation in Pharmacoepidemiology

The Role of Propensity Scores

In observational pharmacoepidemiology, treatment is not randomly assigned. This leads to confounding, as treated and untreated groups differ in their prognostic characteristics [17]. Propensity score methods are a primary tool to control for this confounding by modeling the probability of treatment assignment given observed covariates [1].

The propensity score for a binary treatment A given covariates X is defined as e(X) = P(A=1 | X) [1]. Rosenbaum and Rubin proved that, under the assumption of conditional exchangeability (ignorability), conditioning on the propensity score balances the distribution of observed covariates X between treatment and control groups. This allows for the estimation of causal effects as if treatment had been randomized [1].

Linking Estimands to Propensity Score Methods

The choice of estimand directly influences how propensity scores are applied.

- SATT: When the goal is to estimate the SATT, the analysis is focused on achieving balance and making inferences for the treated individuals. Propensity score matching (PSM) is a natural choice, where each treated individual is matched to one or more untreated individuals with similar propensity scores. The effect is then estimated by contrasting outcomes within these matched pairs, effectively creating a pseudo-population that resembles the treated group but with similar covariate distributions [1] [17].

- SATE/PATE: To estimate the SATE or PATE, which pertain to the entire sample or population, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) is often used. IPTW creates a weighted pseudo-population where the weights,

w = A/e(X) + (1-A)/(1-e(X)), are inversely proportional to the probability of receiving the treatment actually received. This effectively simulates a scenario where every unit had the same chance of being treated, thus allowing for the estimation of an effect for the entire group [1]. A key challenge for PATE is that the study sample may not be perfectly representative of the target population, requiring additional transportability methods [19].

Table 2: Application of Propensity Score Methods by Estimand

| Estimand | Recommended Propensity Score Method | Intuitive Explanation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SATT | Matching (e.g., 1:1 nearest neighbor) | Finds a control "twin" for each treated individual based on their probability of being treated. The effect is the average outcome difference between each treated individual and their twin. | Preserves the original treated group. The quality of the estimate depends on the ability to find good matches for all treated individuals. |

| SATE | Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) | Uses weights to make the treated group look like the full sample and the control group look like the full sample. The weighted groups represent a pseudo-population where everyone had the same chance to be treated or not. | Can be inefficient if some propensity scores are very close to 0 or 1. Requires careful checking of weight distributions. |

| PATE | IPTW + Transportability Methods | First uses IPTW to balance the study sample, then uses a second set of weights (inverse odds of sampling weights) to make the balanced study sample resemble the target population. | Requires data on covariates from the target population. Relies on the strong assumption that all effect modifiers are measured and accounted for [19]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Estimating SATT via Propensity Score Matching

The following workflow details the steps for estimating the SATT using propensity score matching, a common application in pharmacoepidemiology.

Protocol Steps:

Variable Definition [17]:

- Treatment Variable: Clearly define the treatment (e.g., initiation of a new drug vs. an active comparator).

- Outcome Variable: Define the clinical outcome of interest (e.g., hospitalization, mortality).

- Confounding Variables: Select a set of pre-treatment covariates

Xthat are potential common causes of both the treatment and the outcome. This should include demographic information, clinical comorbidities, medication history, and healthcare utilization measures. Leverage clinical expertise and guidelines to build a plausible model.

Estimate Propensity Scores [17]:

- Fit a model, typically a logistic regression, where the treatment indicator is the dependent variable and all confounding covariates are independent variables.

logit(P(A=1 | X)) = β₀ + βâ‚Xâ‚ + ... + βₖXâ‚–- The predicted values from this model are the estimated propensity scores,

ê(X), for each individual. - Advanced methods like Generalized Boosted Models (GBM) or Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART) can also be used for more flexible estimation.

Perform Matching [17]:

- Use a matching algorithm to pair treated individuals with untreated individuals who have a similar propensity score.

- Nearest-neighbor matching is the most common. Each treated individual is matched to the untreated individual with the closest propensity score, often within a pre-specified "caliper" (e.g., 0.2 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score) to prevent poor matches.

- Unmatched individuals are excluded from the subsequent analysis.

Check Covariate Balance [17]:

- After matching, it is imperative to check if the distribution of covariates is now similar between the treated and control groups.

- Use quantitative measures like standardized mean differences (SMD) for each covariate. An SMD below 0.1 (10%) is generally considered indicative of good balance.

- If imbalance persists, the propensity score model or matching parameters may need to be revised (e.g., adding interaction terms, using a different caliper).

Estimate Treatment Effect (SATT):

- In the matched sample, compare the outcomes between the treated and control groups.

- Since matching creates paired data, a paired t-test (for continuous outcomes) or conditional logistic regression (for binary outcomes) can be used. Alternatively, a generalized linear model (e.g., logistic regression) that includes the matched pairs as strata can be fitted [17].

- The resulting coefficient for the treatment variable is an estimate of the SATT.

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Conduct analyses to assess how sensitive the results are to unmeasured confounding. Methods like the Rosenbaum bounds can be used to determine how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to qualitatively change the study conclusions [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Causal Inference Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function in Causal Workflow | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'MatchIt' R Package [17] | Software | A comprehensive tool for performing propensity score matching and other matching methods. | Implements nearest-neighbor, optimal, full, and genetic matching. Integrates with the R ecosystem for balance assessment and outcome analysis. |

| 'cobalt' R Package [17] | Software | Covariate Balance Assessment Tables and Plots. | Provides a wealth of functions and graphics (e.g., love plots) to evaluate covariate balance before and after applying propensity score methods. |

| High-Dimensional Propensity Score (hdPS) [1] | Algorithm | Automates the selection of a large number of potential confounders from healthcare claims data. | Identifies and prioritizes covariates based on their prevalence and potential for confounding. Useful for dealing with the high dimensionality of administrative databases. |

| DAGitty [20] | Software | A browser-based tool for creating, editing, and analyzing causal Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs). | Helps researchers visually articulate and test their causal assumptions, identify minimal sufficient adjustment sets, and detect potential biases like M-bias. |

| Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA) [16] | Conceptual Assumption | The foundational assumption that one unit's outcome is unaffected by another unit's treatment assignment. | Violations (e.g., interference or contagion) complicate causal inference. Must be considered in the study design phase. |

| Generalized Linear Model (GLM) [17] | Statistical Model | The standard workhorse for estimating the propensity score (via logistic regression) and for outcome analysis after matching or weighting. | Flexible framework for different types of outcomes (binary, continuous, count). |

| N-Myristoyl-Lys-Arg-Thr-Leu-Arg | N-Myristoyl-Lys-Arg-Thr-Leu-Arg, CAS:125678-68-4, MF:C42H82N12O8, MW:883.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Uracil-15N2 | Uracil-15N2, CAS:5522-55-4, MF:C4H4N2O2, MW:114.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The explicit definition of the causal estimand—SATE, SATT, or PATE—is a fundamental prerequisite for rigorous pharmacoepidemiological research. SATT is often the most relevant estimand for questions of drug effectiveness and safety in real-world practice, as it directly concerns the patients who are actually prescribed the treatment. Propensity score methods, particularly matching for SATT, provide a powerful design-based approach to minimize confounding by indication in observational studies. However, no analytical method can compensate for a poorly defined causal question. By starting with a clear estimand, researchers can select an appropriate methodology, justify their analytical choices, and ultimately produce evidence that is interpretable and meaningful for clinical and regulatory decision-making.

Pharmacoepidemiology bridges clinical pharmacology and epidemiology, studying the use and effects of medications in large human populations [21]. While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard for establishing efficacy, they have inherent limitations including strict inclusion criteria, short follow-up durations, and limited power for rare adverse events [22] [21]. Consequently, observational studies using real-world data (RWD) provide essential complementary evidence on drug effectiveness and safety in routine clinical practice [23].

However, analyses of observational data face formidable methodological challenges, primarily confounding by indication and various selection biases [1] [24]. In clinical practice, treatments are prescribed selectively based on clinical parameters—healthcare professionals prescribe when anticipating benefit and withhold treatment when concerned about adverse events [1]. This fundamental aspect of clinical decision-making creates systematic differences between treatment groups that, if unaddressed, render crude outcome comparisons uninterpretable [24].

The new-user design and active comparator design constitute a paradigm shift in pharmacoepidemiology that addresses these fundamental methodological challenges [24] [25]. When combined into the active comparator, new user (ACNU) design, these approaches enable observational studies to emulate the design of head-to-head randomized trials, significantly improving the validity of real-world evidence [24] [22]. This article explores the foundational concepts, implementation protocols, and analytical framework of these designs within the context of modern pharmacoepidemiologic research employing propensity score methods.

Conceptual Foundations and Rationale

The Active Comparator Design

The active comparator design (also known as active comparator design) compares the drug of interest ('Drug A') to another active drug ('Drug B') used for the same indication, rather than comparing to non-users [22] [25]. This approach provides three distinct methodological advantages:

First, it increases overlap of measured characteristics between treatment groups. By selecting comparator drugs with similar therapeutic indications, the design creates treatment groups that are more similar in terms of measured baseline characteristics, facilitating more effective statistical adjustment [22].

Second, it reduces potential for unmeasured confounding. Non-user groups often include patients with contraindications to treatment or those with very mild disease, introducing systematic differences in unmeasured characteristics like frailty or disease severity [22]. As demonstrated in studies of influenza vaccine, comparisons with non-users can yield implausibly strong protective effects against all-cause mortality due to such confounding [24]. Active comparator groups minimize these differences by restricting comparisons to patients with clear treatment indications [22].

Third, it addresses more clinically relevant questions. For many chronic conditions where some treatment is necessary, the relevant clinical question is not whether to treat but which treatment to choose [22]. The active comparator design directly answers this question by providing evidence on comparative effectiveness and safety between therapeutic alternatives [22].

The New-User Design

The new-user design (also known as incident user design or initiator design) identifies patients at the time of treatment initiation and begins follow-up at this point [22] [25]. This approach offers several critical advantages over prevalent user designs, which include both new and existing users:

This design enables assessment of time-varying hazards and drug effects. The risk of many adverse events changes over time, often highest shortly after treatment initiation [22]. For instance, studies of TNF-α inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis have demonstrated the highest infection risk occurs within the first 90 days of treatment [22]. Prevalent user designs miss these time-varying hazards because they include persons who have already tolerated the treatment [22].

The new-user approach also ensures appropriate confounding adjustment by clearly establishing a baseline measurement point. This allows investigators to accurately distinguish pretreatment covariates from posttreatment variables, preventing adjustment for mediators that lie on the causal pathway between treatment and outcome [22].

Additionally, this design eliminates immortal time bias when combined with an active comparator. Immortal time refers to follow-up period during which the outcome cannot occur because of the study design [22]. By aligning start of follow-up for both treatment groups at treatment initiation, the new-user design avoids this methodological pitfall [22].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Foundational Design Components

| Design Component | Key Advantages | Methodological Threats Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Active Comparator | - Increases overlap of measured characteristics- Reduces unmeasured confounding- Answers clinically relevant questions | - Confounding by indication- Healthy user/sick stopper effects- Channeling bias |

| New-User Design | - Captures time-varying hazards- Ensures appropriate covariate measurement- Defines accurate treatment duration | - Immortal time bias- Prevalent user bias- Depletion of susceptibles |

Implementation Protocols

Cohort Definition and Eligibility Criteria

Implementing the ACNU design begins with defining a source population and establishing eligibility criteria that emulate the inclusion criteria of a target randomized trial [26]. The process involves:

- Identifying the disease cohort: Define a population of patients with the medical condition for which the study and comparator drugs are indicated [24].

- Establishing drug exposure definitions: Clearly define the pharmaceutical agents of interest, including specific formulations, dosages, and administration routes [27].

- Applying inclusion/exclusion criteria: Apply criteria related to demographics, clinical characteristics, and healthcare utilization to create a study population that would be eligible for either treatment in clinical practice [22].

- Defining the cohort entry date: For both treatment groups, the cohort entry date ("time zero") is the date of treatment initiation after meeting all eligibility criteria [27] [22].

Follow-Up Period and Outcome Assessment

The follow-up protocol must be specified a priori to ensure temporal precedence of exposure before outcome:

- Start of follow-up: Follow-up begins immediately after the cohort entry date for both treatment groups [27] [22].

- End of follow-up: Follow-up continues until the earliest of: outcome occurrence, treatment discontinuation, switching to comparator drug, end of study period, loss to follow-up, or death [27].

- Risk window specification: Define biologically plausible risk windows based on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the drugs under study [27].

- Outcome ascertainment: Implement validated algorithms to identify outcomes of interest, using specific combinations of diagnosis codes, procedures, and medications to maximize specificity and sensitivity [26].

Figure 1: Implementation Workflow for Active Comparator, New-User Design. This diagram illustrates the sequential process of defining study cohorts and follow-up periods according to ACNU principles.

Covariate Selection and Measurement

A critical step in implementing the ACNU design is the appropriate selection and measurement of potential confounders:

- Define baseline period: Establish a fixed period before treatment initiation (e.g., 6-12 months) for assessing all covariates [22].

- Identify confounder domains: Consider demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, healthcare utilization patterns, concomitant medications, and laboratory values [1].

- Apply causal knowledge: Prioritize variables that are risk factors for the outcome and associated with treatment assignment, while avoiding instruments (predictors of treatment only) and mediators (variables on causal pathway) [1] [28].

- Address high-dimensional data: In databases with numerous potential covariates, consider algorithms like the high-dimensional propensity score (hdPS) that systematically select covariates based on their association with both treatment and outcome [1].

Analytical Framework: Integration with Propensity Score Methods

Propensity Score Estimation in ACNU Studies

The ACNU design creates an ideal foundation for propensity score methods by ensuring appropriate covariate measurement and temporal alignment [1] [22]. The propensity score is defined as the probability of treatment assignment conditional on observed baseline covariates [1] [28]. In ACNU studies:

- Model specification: The propensity score model includes all measured baseline covariates identified in the design phase, typically using logistic regression for binary treatments [1] [28].

- Modeling goal: The objective is not prediction perfection but achieving balance in covariates between treatment groups; thus, predictive performance metrics like c-statistics should not guide model specification [1].

- Extended applications: For multiple active comparators, the generalized propensity score can be estimated using multinomial regression models [1].

Propensity Score Application and Balance Assessment

After estimation, propensity scores can be applied through various methods:

- Matching: Creates comparable groups by matching each treated individual with one or more comparator individuals with similar propensity scores [28].

- Weighting: Creates a pseudo-population using inverse probability of treatment weights where covariates are balanced between groups [1].

- Stratification: Divides the study population into strata based on propensity score quantiles and estimates treatment effects within each stratum [28].

- Covariate adjustment: Includes the propensity score as a covariate in the outcome regression model [28].

Table 2: Propensity Score Applications in ACNU Studies

| Application Method | Implementation | Considerations for ACNU Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Matching | 1:1 or variable ratio matching with caliper | - May reduce sample size- Optimizes comparability at individual level- Targets effect in the treated |

| Inverse Probability Weighting | Weights = 1/PS for treated, 1/(1-PS) for untreated | - Maintains original sample size- Creates pseudo-population- Can be unstable with extreme weights |

| Stratification | Subclassification into 5-10 quantiles | - Simple implementation- Allows effect modification assessment- May have residual within-stratum imbalance |

| Covariate Adjustment | Include PS as covariate in outcome model | - Simple approach- Assumes correct functional form- Less robust than other methods |

Crucially, the success of propensity score methods depends on achieving covariate balance between treatment groups after application. Balance should be assessed using standardized differences rather than statistical significance tests, with differences <0.1 generally indicating adequate balance [1] [28].

Outcome Analysis and Effect Estimation

Following propensity score application and balance verification, outcome analysis proceeds:

- Model specification: Choose an appropriate regression model (e.g., Cox proportional hazards, logistic, or Poisson regression) based on the outcome type and distribution [27].

- Effect measure selection: Report both relative (hazard ratios, risk ratios) and absolute (risk differences) effect measures to facilitate clinical interpretation [27].

- Precision estimation: Use robust variance estimators for weighting approaches and account for matched design in matched analyses [1].

- Sensitivity analyses: Conduct analyses to assess potential impact of unmeasured confounding, including quantitative bias analysis and E-values [1].

Figure 2: Analytical Framework Integrating ACNU Design with Propensity Scores. This workflow demonstrates the iterative process of propensity score application with balance assessment as the critical decision point.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Methodological Reagents for ACNU Studies with Propensity Scores

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Active Comparator Drugs | Therapeutic alternative with similar indications | - Should represent viable clinical alternative- Similar mechanism of action preferred but not required- Must have sufficient sample size |

| New-User Cohort | Population of treatment initiators | - Requires washout period to establish new use- Clear operational definition of initiation- Captures all eligible initiators in source population |

| Propensity Score Model | Predicts treatment probability given covariates | - Includes all measured confounders- Avoids overfitting- Focus on balance rather than prediction |

| Balance Metrics | Assesses comparability after PS application | - Standardized differences preferred over p-values- Threshold <0.1 indicates balance- Assess both individual covariates and overall balance |

| High-Dimensional Propensity Score (hdPS) | Algorithmic covariate selection in large databases | - Identifies covariates from data dimensions- Particularly useful in claims data- Requires sufficient sample size |

| 1-Hydroxyoctadecane-d2 | 1-Hydroxyoctadecane-d2, MF:C18H38O, MW:272.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-(~2~H)Ethynyl(~2~H_5_)benzene | 1-(~2~H)Ethynyl(~2~H_5_)benzene, CAS:25837-47-2, MF:C8H6, MW:108.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The new-user design and active comparator design represent foundational methodological advances in pharmacoepidemiology that substantially strengthen the validity of real-world evidence. When implemented through the structured protocols outlined in this article and integrated with propensity score methods, these approaches enable observational studies to more closely approximate randomized trials, addressing pervasive biases like confounding by indication and healthy user effects.

The ACNU framework provides the methodological foundation for generating high-quality evidence on the comparative effectiveness and safety of medical products across their lifecycle. As pharmacoepidemiology continues to evolve with increasing access to large healthcare databases and advanced analytical techniques, these core design principles remain essential for producing reliable evidence to inform clinical practice and regulatory decision-making.

Pharmacoepidemiology, which assesses the use and effects of drugs in large populations, relies heavily on observational studies using secondary healthcare databases. Unlike randomized controlled trials (RCTs), where randomization balances both known and unknown prognostic factors, observational studies are susceptible to multiple systematic biases that can distort the true relationship between drug exposure and patient outcomes [29] [30]. Failure to adequately identify and mitigate these biases can lead to erroneous conclusions about a drug's safety or effectiveness, with significant implications for clinical practice and public health [29] [31]. Within the broader context of a thesis on propensity score methods in pharmacoepidemiological research, this document provides detailed application notes and protocols for three common and impactful biases: immortal time bias, selection bias (with a focus on channeling bias), and confounding by indication. The aim is to equip researchers with structured, practical methodologies to enhance the validity of their observational studies.

Table 1: Definitions and Impact of Key Biases

| Bias Type | Definition | Common Impact on Effect Estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Immortal Time Bias | A period of follow-up during which the outcome under study cannot occur, by design, due to how exposure is defined [32] [33]. | Often exaggerates treatment benefit; can artificially reverse the direction of effect [33] [34]. |

| Channeling Bias | A selection bias where drugs with similar indications are preferentially prescribed to groups of patients with varying baseline prognoses or risk levels [29] [30]. | Can create a spurious association by making one drug appear more harmful or beneficial due to the underlying risk profile of its users. |

| Confounding by Indication | Occurs when the underlying diagnosis or clinical reason for prescribing a drug is itself a risk factor for the outcome under study [29]. | Severely confounds the exposure-outcome relationship, as the treatment indicator is a marker for the severity of the underlying illness. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Immortal Time Bias

Application Notes

Immortal time bias is a pervasive time-related bias that arises from a misalignment between the start of follow-up (time-zero) and the assignment of exposure [32] [33]. It frequently occurs in pharmacoepidemiology when exposure is defined by a first prescription fill that happens some time after a patient qualifies for cohort entry (e.g., after a diagnosis or hospital discharge). The period between cohort entry and this first prescription is "immortal" because the patient must necessarily have survived and not experienced the outcome to have received the exposure [33]. When this immortal person-time is misclassified as exposed time—or excluded entirely—it artificially inflates the survival time of the exposed group, leading to a spurious protective effect [32]. This bias has been shown to substantially distort findings, sometimes even reversing the conclusions of a study [33].

Experimental Protocol for Identification and Mitigation

Objective: To design and analyze an observational cohort study that accurately accounts for immortal time between cohort entry and first drug exposure.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- A longitudinal healthcare database with information on patient demographics, drug prescriptions, hospital admissions, and vital status.

- Clearly defined:

- Cohort entry date (e.g., date of diagnosis, hospital discharge).

- Exposure of interest (e.g., a specific drug class).

- Study outcome (e.g., mortality, hospital readmission).

Procedure:

- Cohort Definition: Define a population of incident users, where patients enter the cohort at the start of a new treatment episode [35]. Apply a washout period to ensure no prior use of the study drug.

- Time-Zero Alignment: Align the start of follow-up (time-zero) and exposure assignment. A patient should be classified as exposed from the date of their first prescription fill onwards. All person-time before this date is considered unexposed.

- Time-Dependent Analysis: Employ a statistical model that treats drug exposure as a time-varying covariate.

- In a Cox proportional hazards model, this means creating a dataset where each patient's follow-up is split into multiple rows based on changes in exposure status.

- Person-time from cohort entry until the first prescription is coded as "unexposed."

- Person-time from the first prescription onward is coded as "exposed."

- Analysis: Run the Cox regression model using the time-varying exposure variable to estimate the hazard ratio for the outcome.

Validation: Where possible, specify a target trial that the observational study aims to emulate, ensuring alignment of time-zero, eligibility criteria, and exposure definition to prevent self-inflicted injuries like immortal time bias [5].

The following diagram illustrates the core methodological flaw and the recommended corrective analysis for immortal time bias.

Figure 1: Analytical Approaches for Immortal Time Bias

Channeling Bias

Application Notes

Channeling bias is a specific form of selection bias prevalent in comparative drug studies. It occurs when a newly marketed drug is "channeled" toward specific patient subgroups, such as those for whom established treatments have failed, those with more severe disease, or those with specific comorbidities [30]. Conversely, the older drug may be used predominantly in a more stable, "healthier" population. This creates a systematic imbalance in prognostic factors between the treatment groups at baseline. If these factors are also associated with the outcome, the resulting comparison is confounded. For example, the new drug may appear to have a higher rate of adverse events simply because it is prescribed to sicker patients [30].

Experimental Protocol for Mitigation Using Propensity Scores

Objective: To balance measured baseline covariates between patients initiating a new drug versus a comparator drug, thereby reducing channeling bias.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- A healthcare database with rich information on patient characteristics, comorbidities, concomitant medications, and healthcare utilization.

- Statistical software capable of performing logistic regression and propensity score matching/weighting.

Procedure:

- Cohort Definition: Define two cohorts of incident users: one for the new drug and one for the active comparator. The cohorts should be contemporary and have similar indications [35].

- Covariate Assessment: Identify and measure all potential pre-treatment confounders (e.g., age, sex, disease severity markers, prior medications, comorbidities) in a baseline period prior to the first prescription.

- Propensity Score (PS) Estimation:

- Fit a logistic regression model where the dependent variable is treatment assignment (1=new drug, 0=comparator).

- The independent variables are all measured baseline covariates.

- The predicted probability from this model is the propensity score—the conditional probability of receiving the new drug given the covariates [30] [36].

- PS Implementation: Choose one of the following methods:

- Matching: Match each patient on the new drug to one or more patients on the comparator drug with a similar PS (using a caliper, e.g., 0.2 of the standard deviation of the PS logit) [36].

- Weighting: Use inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), where weights are created as 1/PS for the new drug group and 1/(1-PS) for the comparator group. This creates a "pseudo-population" where the distribution of covariates is balanced between groups [37] [36].

- Balance Assessment: After applying the PS method, check the balance of all covariates between the treatment groups. The standardized mean difference for each covariate should be <0.1 to indicate adequate balance [36].

- Outcome Analysis: Analyze the association between treatment and outcome in the matched or weighted sample, using a regression model that may further adjust for any residual imbalance.

Limitations: Propensity scores can only adjust for measured confounders. Residual confounding from unmeasured variables (e.g., disease severity not fully captured in the database) may persist [30].

Confounding by Indication

Application Notes

Confounding by indication is perhaps the most fundamental challenge in pharmacoepidemiology. It arises because drugs are prescribed for specific medical conditions, and those conditions are often strong predictors of the study outcome [29]. For instance, studying the effect of antidepressants on mortality is complicated by the fact that depression itself is associated with an increased risk of death. The "indication" for the drug confounds the relationship between the drug (exposure) and the outcome. This bias is inherent in the non-randomized nature of treatment decisions and must be addressed through careful study design and analysis.

Experimental Protocol for Mitigation with an Active Comparator New-User Design

Objective: To mitigate confounding by indication by comparing two active drugs used for the same condition, and to balance baseline risks using propensity scores.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- The same data requirements as in Section 2.2.2.

Procedure:

- Active Comparator Selection: Identify a clinically relevant alternative drug used for the same primary indication as the drug of interest. This helps ensure that the two groups are more comparable in their underlying disease state than if one were compared to non-users [35].

- New-User Design: Restrict the cohort to incident users of either drug, ensuring patients are observed from the start of their treatment episode. This avoids biases associated with prevalent users, who are "survivors" of the early treatment period and may be healthier [35].

- Propensity Score Application: Follow the same steps for PS estimation and implementation as outlined in the protocol for channeling bias (Section 2.2.2). The goal is to create a balanced comparison group that has a similar probability of receiving one drug over the other, based on all measured baseline characteristics.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct sensitivity analyses to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away the observed effect [36].

The following workflow integrates the protocols for addressing channeling bias and confounding by indication through the use of propensity score methods within an active comparator, new-user design.

Figure 2: Propensity Score Workflow for Channeling Bias and Confounding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

In the context of methodological research for mitigating bias, "research reagents" refer to the essential conceptual frameworks, study designs, and analytical techniques required to conduct a valid pharmacoepidemiologic study.

Table 2: Essential Methodological Toolkit for Bias Mitigation

| Tool | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Active Comparator New-User Design | Foundational design that reduces confounding by indication and selection bias by comparing two active drugs and starting follow-up at treatment initiation [35]. | Ensures comparability of treatment groups from the beginning of therapy. |

| Time-Dependent Cox Model | Statistical model used to correctly classify person-time and eliminate immortal time bias by treating drug exposure as a variable that changes over time [32] [33]. | Requires careful data management to split patient follow-up into unexposed and exposed periods. |

| Propensity Score (PS) | A single score (probability of treatment) summarizing all measured baseline covariates; used to balance confounders across treatment groups [37] [30] [36]. | Balances only measured covariates. Model specification and balance assessment are critical. |

| High-Dimensional Propensity Score (hd-PS) | An algorithm that automatically screens a large number of predefined covariates (e.g., diagnosis codes, procedure codes) in administrative data to supplement researcher-specified confounders [5]. | Useful when rich clinical data are lacking; helps control for unmeasured confounding by proxy. |

| Standardized Difference | A balance metric used to assess the effectiveness of PS methods. It is not influenced by sample size, unlike p-values [36]. | A value <0.1 after PS adjustment indicates adequate balance for a covariate. |

| Target Trial Emulation | A framework for designing observational studies by explicitly specifying the protocol of a hypothetical RCT that the study aims to emulate [5]. | Helps avoid common biases (like immortal time) by forcing alignment of time-zero, eligibility, and treatment strategies. |

| Sulfadoxine D3 | Sulfadoxine D3, CAS:1262770-70-6, MF:C12H14N4O4S, MW:313.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aphidicolin 17-acetate | Aphidicolin 17-acetate, MF:C8H6BrF2NO3, MW:282.04 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Propensity Score Analysis in Real-World Data

A Step-by-Step Guide to Propensity Score Estimation and Covariate Selection

In pharmacoepidemiological studies, researchers routinely use real-world data to assess the safety and effectiveness of pharmaceutical products. Unlike randomized controlled trials, observational studies are prone to confounding bias due to imbalanced baseline characteristics between treatment groups. Propensity score (PS) methods have emerged as a powerful statistical approach to address this challenge by creating pseudo-randomized conditions when analyzing observational data. A propensity score, defined as the probability of treatment assignment conditional on observed covariates, enables researchers to simulate the balancing properties of randomization.

The growing availability of large-scale healthcare databases has expanded opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research, but it has also intensified methodological challenges related to confounding control and model specification. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for propensity score estimation and covariate selection, with particular emphasis on applications in drug development and safety research. We detail both established and emerging methodologies, including machine learning approaches and hybrid techniques that combine propensity scores with prognostic scores to enhance causal inference from non-randomized study designs.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Defining the Propensity Score

The propensity score for subject i (i = 1, ..., N) is defined as the conditional probability of receiving the treatment given the observed covariates: e(Xi) = P(Ai = 1 | Xi) where Ai is the treatment indicator (1 for treatment, 0 for control) and X_i is the vector of observed pre-treatment covariates. Rosenbaum and Rubin demonstrated in 1983 that, under the strong ignorability assumption, treatment assignment and potential outcomes are independent conditional on the propensity score. This foundational property allows researchers to adjust for confounding by balancing the distribution of observed covariates across treatment groups based on the propensity score.

The strong ignorability assumption requires two conditions: first, that the treatment assignment is independent of potential outcomes given the covariates (unconfoundedness), and second, that every subject has a positive probability of receiving either treatment (positivity). In pharmacoepidemiological applications, these assumptions must be carefully considered in the context of the clinical question and available data. Violations of these assumptions, particularly unmeasured confounding, remain a fundamental limitation that propensity scores cannot fully address.

Covariate Selection Principles and Approaches

Causal diagrams (directed acyclic graphs) provide a theoretical framework for identifying an appropriate set of confounders for inclusion in the propensity score model. The goal is to include covariates that are associated with both treatment and outcome while avoiding instruments (variables affecting only treatment) and mediators (variables on the causal pathway between treatment and outcome). Including instrumental variables can increase variance without reducing bias, while including mediators can introduce overadjustment bias by blocking causal pathways.

For pharmacoepidemiological studies, researchers should prioritize covariates with known clinical relevance to the disease process and treatment decision-making. A structured approach to covariate selection might include:

- Clinical knowledge-based selection: Using subject matter expertise to identify potential confounders

- High-dimensional propensity score (hdPS): Data-adaptive algorithm for selecting covariates from large healthcare databases

- Hybrid approaches: Combining clinical knowledge with automated variable selection techniques

Recent methodological research emphasizes that prioritizing covariates strongly associated with the outcome, rather than treatment, generally leads to better bias reduction in treatment effect estimates. This principle has motivated the development of prognostic score-based approaches to propensity score estimation and evaluation.

Methodological Approaches to Propensity Score Estimation

Traditional Statistical Methods

Logistic regression represents the most widely used approach for propensity score estimation. The model specification follows standard logistic regression framework, with treatment status as the dependent variable and selected covariates as independent variables: logit(P(Ai = 1 | Xi)) = β0 + β1X1i + ... + βpX_pi

The reference method in pharmacoepidemiology typically involves logistic regression with covariates selected based on clinical knowledge and prior literature. This approach performs well when the relationship between covariates and treatment assignment is linear and additive, and when all relevant confounders have been correctly identified and measured. However, model misspecification remains a concern, particularly when complex interactions or nonlinear relationships exist in the data.

Regularized regression methods, such as LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator), introduce penalty terms to the likelihood function to handle high-dimensional covariate spaces: β̂ = argminβ { -l(β | A, X) + λΣ|β_j| } where l(β | A, X) is the log-likelihood function and λ is the tuning parameter that controls the strength of the penalty. LASSO performs both variable selection and shrinkage, making it particularly useful when dealing with numerous potential confounders. Simulation studies have shown that LASSO performs well in linear settings with small sample sizes and common treatment prevalence [38].

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning methods offer flexible alternatives to traditional logistic regression, particularly for capturing complex relationships in high-dimensional data. The following table summarizes key machine learning approaches for propensity score estimation:

Table 1: Machine Learning Methods for Propensity Score Estimation

| Method | Key Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO | L1 regularization with variable selection | Automatic variable selection, handles correlated predictors | Shrinks coefficients toward zero, may exclude weak predictors | Best in linear settings with small samples and common treatment prevalence [38] |

| XgBoost | Gradient boosted decision trees | Captures complex nonlinearities and interactions, robust to outliers | Computationally intensive, requires careful tuning | Outperforms in nonlinear settings with large samples and low treatment prevalence [38] [39] |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Neural network with multiple hidden layers | Models complex nonlinear relationships, handles high-dimensional data | Requires extensive tuning, prone to overfitting without proper validation | Performs similarly to other ML methods in complex data scenarios [38] |

Model Averaging and Hybrid Approaches

Model averaging approaches integrate multiple propensity score estimates to improve robustness against model misspecification. The model-averaged propensity score is calculated as: ē(Xi) = Σλm êm(Xi) where λm are mixing parameters that sum to 1, and êm(X_i) represents the propensity score estimate from candidate model m.

Recent methodological developments have introduced prognostic score-based model averaging, which selects the optimal mixing parameters by minimizing between-group differences in prognostic scores (predicted outcomes under control) rather than focusing solely on covariate balance. This approach recognizes that imbalance in prognostic scores is more strongly associated with bias in treatment effect estimates than imbalance in individual covariates. Simulation studies demonstrate that this method consistently yields lower bias and less variability in treatment effect estimates across various scenarios [40].

Practical Implementation Protocol

Step-by-Step Estimation Procedure

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for propensity score estimation and application:

Diagram 1: Propensity Score Analysis Workflow

Step 1: Define the Causal Question and Target Estimand Clearly specify the treatment comparison, outcome, target population, and causal contrast of interest. Determine whether the target estimand is the average treatment effect in the overall population (ATE), treated population (ATT), or overlap population (ATO). This decision guides the selection of appropriate propensity score methods [41].

Step 2: Assemble the Study Cohort and Define Variables Identify the source population, eligibility criteria, and index dates. Precisely define treatment exposure, outcome, and potential confounders using structured healthcare data. Implement a covariate assessment period preceding treatment initiation to ensure proper temporal ordering.

Step 3: Select Covariates for Inclusion Incorporate covariates that are potential common causes of treatment and outcome. Use clinical knowledge, literature review, and data-driven approaches. Consider using high-dimensional propensity score (hdPS) algorithms when dealing with large-scale healthcare data with numerous potential covariates [42].

Step 4: Estimate Propensity Scores Select an appropriate estimation method based on sample size, treatment prevalence, and data complexity. For conventional analyses, use logistic regression with pre-specified covariates. For high-dimensional data or complex relationships, consider machine learning approaches like LASSO or XgBoost with proper hyperparameter tuning.