Optimizing Cancer Combination Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide to Scheduling with Optimal Control Theory

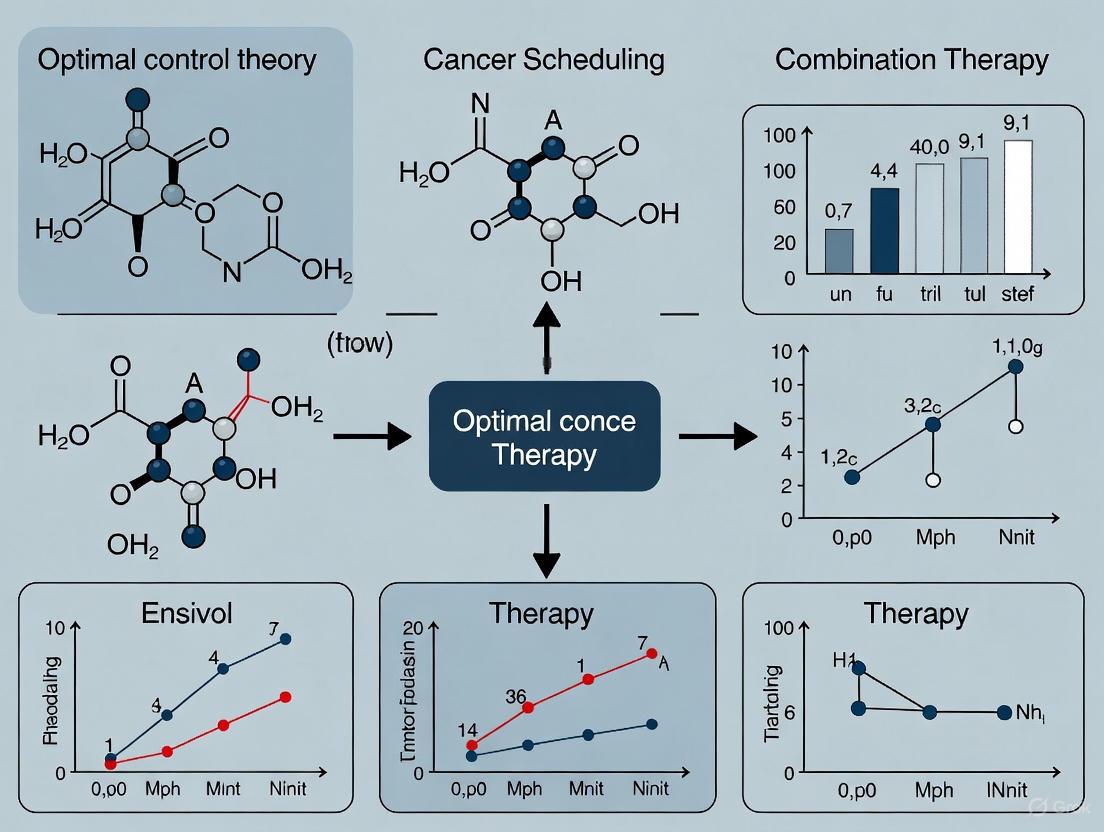

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Optimal Control Theory (OCT) to optimize the scheduling of cancer combination therapies.

Optimizing Cancer Combination Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide to Scheduling with Optimal Control Theory

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Optimal Control Theory (OCT) to optimize the scheduling of cancer combination therapies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mathematical principles of OCT and its use in designing personalized treatment regimens. The content delves into methodological advances, including the use of ordinary differential equation (ODE) models and pan-cancer signaling pathways to simulate tumor dynamics and predict treatment responses. It addresses key challenges such as managing toxicity, overcoming drug resistance, and accounting for patient heterogeneity. Furthermore, the article reviews validation techniques and comparative analyses of different OCT strategies, highlighting their potential to improve therapeutic efficacy, minimize side effects, and pave the way for more precise and effective cancer treatments.

The Foundation of Optimal Control in Oncology: From Basic Principles to Modern Combination Therapy

Core Concepts of Optimal Control Theory

Optimal Control Theory (OCT) is a mathematical framework for determining how to steer a dynamic system over time to optimize a specific performance criterion while adhering to system constraints [1]. It bridges the gap between theory and practice, allowing for the solving of complex problems by finding the best control inputs over time [2].

Fundamental Problem Formulation

Formally, an optimal control problem aims to minimize a cost functional [1] [3]: [ J[x(·),u(·),t0,tf] := E[x(t0),t0,x(tf),tf] + \int{t0}^{t_f} F[x(t),u(t),t] dt ] This is subject to the system's dynamic constraints: [ \dot{x}(t) = f[x(t),u(t),t], ] as well as any path and boundary constraints [1]. In this formulation:

- ( x(t) ) represents the state variables (e.g., tumor cell count, immune cell concentration) [2] [3].

- ( u(t) ) represents the control inputs (e.g., drug dosage, radiation intensity) [2] [3].

- The function ( F ) quantifies the running cost (e.g., transient tumor size, drug toxicity), while ( E ) is the terminal cost [1].

Key Mathematical Principles

Two primary methods for solving these problems are:

- Pontryagin's Maximum Principle: This necessary condition leads to a Pontryagin system, which introduces co-state variables ((λ)) that represent the marginal value of the state variables [1] [4]. The solution involves defining a Hamiltonian function ( H = F + λ^T f ) and finding the control that minimizes ( H ) at each point in time [2] [4].

- Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman Equation: This provides a sufficient condition for optimality via dynamic programming [1].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for deriving an optimal control using Pontryagin's Maximum Principle.

OCT in Cancer Therapy: FAQs & Troubleshooting

FAQ: Core Concepts

What makes OCT suitable for cancer therapy optimization? Cancer is a dynamic system where tumor cells evolve and interact with treatments and the immune system. OCT provides a rigorous framework to compute the best therapeutic regimen—optimizing the timing, dosage, and combination of treatments to maximize tumor cell kill while minimizing toxicity to healthy tissues [5] [3]. It allows for the in-silico testing of numerous alternative regimens that are impossible to systematically evaluate in clinical trials [5].

How is a cancer treatment problem formally translated into an OCT problem?

- State Variables (x(t)): Quantities describing the system's state (e.g., populations of cancer cells, immune cells like CD8+ T cells, and healthy tissue cells) [6] [3].

- Control Inputs (u(t)): Adjustable therapy parameters (e.g., doses of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiation) [5] [3].

- Dynamics (f): A system of differential equations modeling the interactions between state variables and controls [3].

- Cost Functional (J): A mathematical expression balancing treatment goals (e.g., minimize tumor size and treatment toxicity over time) [3].

What are the main types of control strategies used?

- Open-Loop Control: The optimal treatment schedule is computed upfront for the entire treatment period. It is sensitive to model inaccuracies.

- Closed-Loop (Feedback) Control: The treatment plan is adjusted in real-time based on frequent measurements of the patient's response (e.g., via biomarkers or imaging), making it more robust to uncertainties [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Computational Challenges

Problem: Model Predictions Diverge from Expected Biological Behavior

- Potential Cause 1: Poorly Calibrated Model Parameters. The mathematical model's parameters (e.g., cell growth/death rates) are not accurately tuned to represent a specific patient's tumor biology.

- Solution: Increase the use of patient-specific data for calibration. Utilize longitudinal data (e.g., from quantitative imaging or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) assays) to inform and adjust the model parameters [5] [7].

- Potential Cause 2: Oversimplified System Dynamics. The model may lack crucial biological mechanisms, such as drug resistance, immune suppression, or spatial heterogeneity.

- Solution: Develop multiscale models that incorporate additional layers of biology, such as intracellular signaling networks or the tumor microenvironment [5]. Consider using spatial transcriptomics or single-cell sequencing data to inform these models [7].

Problem: Optimization Fails to Converge or Yields Impractical Solutions

- Potential Cause 1: Violation of Physical Constraints. The computed control may suggest drug doses that are toxic or physically impossible to administer.

- Solution: Re-formulate the problem with hard constraints on the maximum dose per fraction (for radiation) or cumulative dose (for chemotherapy) [5] [2] [3]. Explicitly include constraints on healthy tissue toxicity in the cost functional [3].

- Potential Cause 2: Non-convexity of the Optimization Landscape. The problem may have multiple local minima, causing the solver to get stuck in a sub-optimal solution.

- Solution: Employ global optimization algorithms or stochastic methods. Try different initial guesses for the control trajectory to explore the solution space. For nonlinear systems, consider methods like the State-Dependent Riccati Equation (SDRE) [6].

Problem: The Control Strategy is Sensitive to Small Measurement Errors

- Potential Cause: Lack of Observability. Not all critical state variables (e.g., resistant cancer cell sub-populations) can be accurately estimated from available clinical measurements.

- Solution: Perform an observability analysis of your model. Invest in developing and integrating better biomarkers and sensing technologies (e.g., advanced ctDNA analysis) that provide a more complete picture of the tumor state [7] [3].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol: Applying OCT to a Combination Therapy Model

This protocol outlines the steps for formulating and solving an optimal control problem for cancer combination therapy scheduling.

1. System Identification and Model Formulation:

- Objective: Develop a mathematical model of the tumor-immune-treatment interplay.

- Methodology:

- Select state variables (e.g., sensitive cancer cells, resistant cancer cells, CD8+ T cells, normal tissue cells) [6] [3].

- Based on literature and preclinical data, write a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) describing the rates of change for each state variable. Include terms for natural growth/decay, immune-mediated killing, and drug-induced cell death [6] [3].

- For chemotherapy, model the drug effect as proportional to the drug concentration and the cell population size. For immunotherapy, model the activation and proliferation of immune cells [3].

2. Optimal Control Problem Formulation:

- Objective: Define the goal of therapy as a mathematical cost functional.

- Methodology:

- Define the cost functional ( J ). A common form is: ( J = \int{0}^{T} [x{tumor}(t) + w \cdot u^2(t)] dt ) where ( u(t) ) is the drug dose and the weight ( w ) balances the importance of minimizing tumor size versus minimizing cumulative drug toxicity [3].

- Set constraints: Define upper bounds for ( u(t) ) (maximum tolerated dose) and for the nadir of normal tissue cells [3].

3. Numerical Solution and Simulation:

- Objective: Compute the optimal drug administration schedule ( u^*(t) ).

- Methodology:

- Discretize the continuous-time problem for numerical computation.

- Use appropriate numerical solvers. The table below compares several methods used in recent research [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Numerical Methods for Optimal Control

| Method | Description | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| IPOPT | Interior Point Optimizer | An open-source tool for large-scale nonlinear optimization; suitable for direct transcription methods [6]. |

| SDRE | State-Dependent Riccati Equation | Adapts linear control methods (LQR) for nonlinear systems; provides a suboptimal feedback law [6]. |

| ASRE | Approximate Sequence Riccati Equation | A globally optimal feedback control approach for nonlinear systems [6]. |

4. Validation and Analysis:

- Objective: Assess the performance and robustness of the optimal protocol.

- Methodology:

- Simulate the system dynamics under the computed optimal control.

- Perform sensitivity analysis by perturbing model parameters and initial conditions to test the robustness of the protocol.

- Compare the outcome (e.g., final tumor size, total drug used) against standard-of-care dosing schedules [6].

Quantitative Results from Recent Studies

The following table summarizes sample outcomes from a computational study applying different OCT methods to a cancer therapy model, demonstrating the performance of various controllers in minimizing a defined cost function [6].

Table 2: Sample Performance Metrics from an OCT Study [6]

| Control Method | Cost Value (J) | Final Tumor Cell Count (C) | Final CD8+ T Cell Count (C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPOPT | 52.3573 | 0.0007 | 1.6499 |

| SDRE | 52.4240 | 0.0006 | 1.6499 |

| ASRE | 52.4240 | 0.0006 | 1.6499 |

Note: (C) denotes a continuous dosing strategy. The lower cost value for IPOPT indicates a marginally better performance in this specific optimization [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for OCT Cancer Therapy Research

| Item / Reagent | Function in OCT Research |

|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Solvers | Software (e.g., in MATLAB, Python's SciPy) to numerically simulate the system dynamics and solve state/costate equations [3]. |

| Nonlinear Programming Solvers | Algorithms (e.g., IPOPT) used in direct methods to solve the discretized optimization problem [6] [2]. |

| Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Models | In-vivo models that provide realistic, patient-specific data for calibrating and validating the biological models [5]. |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | A liquid biopsy biomarker used to measure tumor burden and response, providing real-time data for feedback control or model validation [7]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Technology to analyze gene expression in the context of tissue architecture, informing models of the tumor microenvironment and heterogeneity [7]. |

| HIV gp120 (318-327) | HIV gp120 (318-327), MF:C48H80N16O12, MW:1073.2 g/mol |

| sGC activator 1 | sGC activator 1, CAS:2101645-33-2, MF:C27H22ClF5N6O3, MW:608.9 g/mol |

Visualizing Therapy Action and Workflow

Many chemotherapeutic agents are cell-cycle specific. The following diagram illustrates the phases of the cell cycle and where different classes of drugs act, which is a critical consideration for building accurate dynamic models [3].

Historical Context and Clinical Limitations of Standard Combination Therapy Schedules

The establishment of standard combination therapy schedules in oncology has been largely shaped by the clinical trial system, which focuses on determining maximum tolerated doses and average efficacy for a population. This approach makes it systematically impossible to evaluate all possible dosing and scheduling options. Consequently, multi-modality treatment policies remain largely empirical, subject to individual clinicians' experience and intuition rather than being derived from rigorous, personalized optimization [5]. The paradigm has historically followed a "stepped care" approach, often initiating treatment with monotherapy, despite evidence that most patients require combination therapy for effective disease control [8]. This guideline-practice gap arises because clinical trials operate under strict protocols with high patient adherence, whereas real-world clinical practice must contend with variable patient compliance and physician concerns about over-treatment [8].

Core Clinical Limitations of Standard Schedules

Therapeutic Inertia and the Guideline-Practice Gap

A significant limitation of standard scheduling is therapeutic inertia. Real-world data demonstrates that once patients are initiated on monotherapy, clinicians rarely intensify treatment even when control is inadequate. A study of 125,635 hypertensive patients revealed that 80.4% were initially prescribed monotherapy. After three years, only 36% of these had been switched to combination therapy, compared to 78% of those who started with combination drugs [8]. This inertia means the initial therapeutic strategy often dictates the final management plan, frequently leading to suboptimal disease control.

Ignoring Scheduling and Sequencing Effects

Preclinical studies demonstrate that the sequence and timing of drug administration significantly impact the emergence of resistance and overall efficacy. Research in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) evaluating crizotinib and navitoclax combinations tested 696 sequential and concomitant treatment regimens. The findings revealed that patterns of resistance depend critically on the schedule and sequence in which drugs are given [9]. For example:

- Drug holiday duration significantly influences outcomes. In a two-cycle single-agent navitoclax regimen, increasing recovery periods from 2 days to 10 days between cycles caused a 9-fold increase in viable cells at the end of the second cycle [9].

- Dose proportions in equivalent combinations affect long-term efficacy. Two IC90-equivalent concomitant combinations (1μM navitoclax/1μM crizotinib vs. 0.5μM navitoclax/2.5μM crizotinib) showed dramatically different outcomes over 26 days, with the latter proving more effective at controlling growth and reducing mammosphere formation [9].

One-Size-Fits-All Dosing Paradigms

Systemic therapy dosing typically relies on body surface area (BSA), a practice established over 60 years ago for inter-species dosage extrapolation. However, BSA fails to account for critical factors affecting drug distribution and efficacy, including hepatic and renal function, body composition, enzyme activity, drug resistance, gender, age, and concomitant medications [5]. Consequently, BSA-based dosing does not effectively reduce variability in drug efficacy between patients [5].

Inadequate Consideration of Resistance Evolution

Standard scheduling often fails to account for the eco-evolutionary dynamics of cancer resistance. Treatment is frequently administered continuously until disease progression, effectively applying maximal selective pressure that enriches resistant clones [10]. Feedback mechanisms can be triggered by specific schedules; for instance, certain drug combinations can upregulate anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-xL via negative feedback loops, associated with increased phosphorylated AKT and ERK, rendering cells insensitive to retreatment [9].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Standard Combination Therapy Schedules

| Limitation | Clinical Consequence | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Inertia | Delayed treatment intensification leading to inadequate disease control | Only 36% of patients on initial monotherapy switch to combinations within 3 years [8] |

| Fixed Dosing Intervals | Suboptimal drug exposure and recovery periods | 9-fold increase in viable cells with longer drug holidays (2 vs. 10 days) [9] |

| BSA-Based Dosing | High inter-patient variability in efficacy and toxicity | Fails to account for organ function, body composition, and other key factors [5] |

| Ignoring Drug Sequencing | Accelerated emergence of therapeutic resistance | Resistance patterns depend entirely on administration sequence [9] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Investigating Therapy Scheduling

| Research Tool | Function in Scheduling Research | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Integrated Barcodes | Tracks clonal dynamics and population evolution under different schedules | Identifying resistant subpopulations that emerge under specific sequencing [9] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNAseq) | Reveals transcriptional patterns linking treatment schedule to resistance mechanisms | Characterizing fitness of individual cell clones under specific treatment schedules [9] |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Identifies synthetic lethal interactions for rational combination design | Genome-wide screens to find novel therapeutic combinations targeting resistance [10] |

| Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Models | Predicts drug concentration and effect relationships for personalized scheduling | In silico optimization of administration schedules based on patient-specific parameters [11] |

| Bruceine J | Bruceine J, MF:C25H32O11, MW:508.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dap-81 | Dap-81, MF:C25H20N6O4, MW:468.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Scheduling Research

Protocol: Extended In Vitro Scheduling Screen

Background: Standard 3-day viability assays assess killing potential but fail to model schedule-dependent resistance emergence [9].

Methodology:

- Cell Model: MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cells.

- Treatment Regimens: Test single agents, sequential administrations, and concomitant combinations.

- Schedule Variations:

- Treatment cycle durations: 1, 2, or 3 days

- Drug-free recovery periods: 2, 5, or 10 days

- Total study duration: 26 days

- Assessment Endpoints:

- Viable cell counts at schedule completion

- Apoptosis rates via flow cytometry

- Clonal dynamics using DNA barcoding

- Transcriptional profiling via scRNAseq

- Analytical Methods:

- Flow cytometric analysis of surface markers (EpCAM, CD24, CD44)

- Mammosphere formation assays for tumorigenicity

- Western blotting for apoptotic regulators (Bcl-xL, pAKT, pERK)

Application: This protocol generated 696 unique treatment conditions, revealing that specific scheduling parameters dramatically influence resistance development and long-term efficacy [9].

Protocol: Markov Decision Process for Treatment Optimization

Background: MDPs provide a mathematical framework for optimizing sequential decisions under uncertainty, ideal for therapy scheduling [12] [13].

Methodology:

- State Space Definition: Patient health states (e.g., responsive, stable, progressive disease) incorporating tumor burden and normal tissue side effects [13].

- Action Space: Treatment options including no treatment, single modalities, or combinations with defined doses [14].

- Transition Probabilities: Calibrated from cohort data or patient-specific models.

- Reward Function: Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) balancing tumor control against treatment toxicity [12].

- Optimization Algorithm: Dynamic programming to derive policy maximizing discounted expected QALYs.

Application: This approach has been used to determine optimal intervention timing, duration, and sequencing for breast cancer patients, revealing that optimal strategies often differ from standard protocols [14].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q: Our in vitro combination shows strong synergy in short-term assays, but fails in longer-term models. What factors should we investigate?

A: Focus on schedule-dependent resistance mechanisms:

- Clonal Evolution: Use DNA barcoding to track whether different administration sequences select for distinct resistant subpopulations [9].

- Feedback Signaling: Analyze adaptive responses in survival pathways (e.g., AKT, ERK phosphorylation) following drug exposure [9].

- Drug Holiday Impact: Systematically vary recovery periods between treatment cycles; even 2-day differences can cause 9-fold changes in viable cell mass [9].

Q: How can we prioritize which of many possible drug combinations to test for schedule optimization?

A: Implement a tiered screening approach:

- Primary Unbiased Screens: Use high-throughput combination screening to identify unexpected synergistic interactions [10].

- Mechanistic Follow-up: Employ siRNA screens to identify synthetic lethal interactions that inform rational combination design [10].

- Computational Prioritization: Apply PK/PD modeling to simulate different scheduling scenarios before laborious experimental testing [11].

Q: What computational approaches best address the multi-dimensional optimization of therapy schedules?

A: Several mathematical frameworks show promise:

- Optimal Control Theory: Formulate therapy design as a control problem aiming to optimize an objective function (e.g., tumor reduction minus toxicity costs) [5] [11].

- Markov Decision Processes: Model treatment as a sequential decision process with states, actions, and rewards to derive optimal policies [12] [13] [14].

- Game-Theoretic Approaches: Model cancer as a reactive player that evolves resistance, enabling strategies that preempt resistance evolution [12].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Treatment Resistance Pathways

Optimal Control Framework

Table 3: Experimental Data on Scheduling Parameters and Outcomes

| Scheduling Parameter | Range Tested | Impact on Outcome | Quantitative Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Holiday Duration | 2, 5, 10 days | Viable cell mass | 9-fold increase with longer holidays (2 vs. 10 days) [9] |

| Concomitant Dose Ratio | 1:1 vs. 0.5:2.5 (Nav:Criz) | Long-term growth control | 6-times greater viable cells with suboptimal ratio [9] |

| Treatment Cycle Duration | 1, 2, 3 days | Apoptotic induction | Varies by specific sequence and timing [9] |

| Administration Sequence | Drug A→B vs. B→A | Resistance mechanism | Distinct clonal selection patterns [9] |

This guide provides technical support for researchers implementing control-theoretic frameworks in cancer combination therapy scheduling.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: System State Model Fails to Reflect Observed Tumor Dynamics

Problem: Your mathematical model, which describes the system state (e.g., tumor cell populations), does not align with experimental or clinical data. The model's predictions are inaccurate.

Solution: Perform rigorous system identification and model validation.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reassess Model Structure: Verify that your model's equations reflect the correct biological phenomena. A common model for heterogeneous tumors uses a system of coupled ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to represent different cell populations (the state vector, x) and their interactions [15].

- Verify Model Observability: Ensure that the system's internal states (e.g., counts of specific cell subpopulations) can be inferred from your available output measurements (e.g., total tumor volume) over time [16].

- Parameter Estimation: Use experimental data to calibrate model parameters (e.g., cell growth rates, drug efficacy coefficients). Employ nonlinear programming techniques and differential equation solvers, such as the Implicit Euler method, to achieve accurate fits [17].

- Validate with New Data: Test the calibrated model against a new, unused dataset to confirm its predictive power.

Related Experiments: The work on constrained optimal control for cancer chemotherapy utilizes discretization and nonlinear programming (e.g., with IPOPT solver) to determine model parameters and extremal solutions that satisfy system constraints [17].

Guide 2: Optimal Control Solution is Computationally Intractable or Yields Counter-Intuitive Dosing

Problem: The algorithm to find the optimal control (drug schedule) fails to converge, takes too long, or suggests a therapy regimen that is clinically impractical (e.g., excessive toxicity).

Solution: Analyze and refine your objective function and control constraints.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Inspect the Objective Function: The objective function (or cost function, ( J )) must precisely encode the treatment goal. A typical formulation aims to minimize the tumor cell count at the end of the treatment horizon while penalizing excessive drug usage and toxicity [15] [18]. For example, a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) cost function is of the form ( J{LQR} = \sum ( \mathbf{x}^T Q \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{u}^T R \mathbf{u} ) ), where ( Q ) and ( R ) are weighting matrices that balance the importance of state regulation against control effort [19].

- Check Control Constraints: Ensure that the bounds on your control variables (u), which represent drug doses, are physiologically realistic (e.g., ( 0 \leq uk \leq 1 ), representing the minimum and maximum effective doses) [15].

- Apply Pontryagin's Maximum Principle (PMP): For complex, non-linear systems, PMP is a powerful tool to derive necessary conditions for optimality. This can reveal whether the optimal solution has a "bang-bang" structure (switching between min and max doses) or is a smoother, singular arc [17].

- Simplify the Model: If the system is too complex, consider if a linear or "pseudo-linear" approximation (e.g., using the State-Dependent Riccati Equation approach) is sufficient for your control objectives [19].

Related Experiments: Studies on drug-induced plasticity use PMP to show that the optimal strategy often involves steering the tumor to a fixed equilibrium composition between sensitive and tolerant cells, balancing cell kill against tolerance induction [18].

Guide 3: Therapy Schedule Performs Poorly Against Heterogeneous or Evolving Tumors

Problem: A treatment schedule that is optimal in simulation fails in a real-world context due to tumor heterogeneity, the emergence of drug-resistant clones, or phenotypic plasticity.

Solution: Incorporate evolutionary dynamics and adaptive (closed-loop) control strategies.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Expand System States: Augment your state vector to explicitly include multiple cell populations (e.g., drug-sensitive and drug-tolerant/resistant cells) [15] [18]. Model transitions between these states, which may themselves be dependent on drug concentration (u) [18].

- Implement Adaptive Therapy Principles: Shift from a static, open-loop schedule to a closed-loop feedback control system. Design the controller to monitor tumor response (e.g., via biomarkers) and dynamically adjust the dosing (the control input) to maintain a stable tumor burden, exploiting the competitive interference between cell types [20] [21] [22].

- Validate with Evolutionary Models: Test your control strategy using models that integrate evolutionary game theory, where the "fitness" of different cell types determines the outcome of millions of simulated competitions within the tumor ecosystem [21].

Related Experiments: Clinical trials in prostate cancer based on adaptive therapy principles cycle treatment on and off in response to tumor biomarker levels, successfully delaying progression by maintaining a population of therapy-sensitive cells that suppress resistant ones [20].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between open-loop and closed-loop control in therapy scheduling?

- A: In open-loop control (feedforward), the drug administration schedule is pre-determined and does not change based on the patient's response. An example is a fixed three-week chemotherapy cycle [23]. In closed-loop control (feedback), the drug dose is continuously adjusted based on feedback measurements of the process variable (e.g., tumor size or a biomarker). A "closed-loop controller" uses this feedback to minimize the deviation between the desired and actual state [23]. Adaptive therapy is a prime example of a closed-loop strategy in oncology [20].

Q2: How do I decide on the weighting factors in my objective function?

- A: The weighting matrices ( Q ) and ( R ) in an LQR objective function, for instance, are often determined through a combination of sensitivity analysis and clinical intuition. There is no single formula. You should perform a systematic sweep of different weights and observe the resulting trade-off between tumor cell reduction (governed by ( Q )) and drug usage/toxicity (governed by ( R )) [19]. The chosen weights should produce a control trajectory that aligns with clinical priorities.

Q3: My model is highly nonlinear. What control methods are available beyond LQR?

- A: For nonlinear systems, several advanced techniques are available. The State-Dependent Riccati Equation (SDRE) method is a powerful approach that transforms the nonlinear system into a "pseudo-linear" structure, allowing for the application of extended LQR-like techniques at each time step [19]. Another foundational method is the Pontryagin Maximum Principle (PMP), which provides necessary conditions for optimality and is widely used to derive optimal control policies for complex biological systems [17].

Q4: What is a "bang-bang" control solution and when does it occur?

- A: A "bang-bang" control solution is one where the optimal drug dose is always at either its minimum (e.g., zero) or maximum permissible value, switching abruptly between these extremes. This type of solution frequently arises in cancer chemotherapy models when using the Pontryagin Maximum Principle, particularly when the system dynamics and objective function are linear in the control variable [17].

Experimental Data and Models

The table below summarizes key parameters and components from cited control-theoretic experiments in cancer therapy.

Table 1: Key Components of Control-Theoretic Frameworks in Cancer Therapy Research

| Component | Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| System States (x) | Variables describing the dynamic system. | Counts of drug-sensitive and drug-tolerant cancer cells [18]; Tumor volume/weight [19]. |

| Control Inputs (u) | Adjustable variables that influence the system. | Effective drug concentration/dose of chemotherapeutic agents [15] [19]. |

| Objective Function (J) | A mathematical expression defining the goal of control. | Minimize tumor cell count at final time + minimize total drug usage/toxicity [18] [19]. |

| Key Parameters | Constants that define system behavior. | Cell growth/death rates (λ, d); Phenotypic transition rates (μ, ν) [18]; Pharmacodynamic parameters [17]. |

| Optimization Method | Algorithm used to find the optimal control. | Pontryagin Maximum Principle (PMP) [17]; Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) [19]; State-Dependent Riccati Equation (SDRE) [19]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Control-Theoretic Cancer Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Systems | The core mathematical model describing the rates of change of tumor cell populations under treatment [17] [15]. |

| Nonlinear Programming Solver (e.g., IPOPT) | Software used to numerically solve optimization problems with nonlinear constraints, such as finding parameters or optimal controls [17]. |

| Applied Modelling Programming Language (AMPL) | An algebraic modeling language for describing and solving large-scale optimization problems [17]. |

| Pontryagin Maximum Principle (PMP) | A fundamental theorem used to derive necessary conditions for an optimal control, often pointing to bang-bang solution structures [17]. |

| State-Dependent Riccati Equation (SDRE) | A method for designing suboptimal controls for nonlinear systems by solving a sequence of algebraic Riccati equations [19]. |

Framework Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the logical structure and information flow of a closed-loop, control-theoretic framework for adaptive cancer therapy.

Diagram 1: Closed-loop control framework for adaptive therapy.

Mathematical Modeling of Tumor-Immune-Treatment Dynamics using Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs)

Foundational ODE Models for Tumor-Immune Dynamics

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models are a cornerstone for quantifying the complex interactions between tumors, immune cells, and therapeutic agents. The table below summarizes fundamental model structures used in the field [24] [25].

Table 1: Core ODE Model Structures for Tumor-Immune-Treatment Dynamics

| Model Purpose | Exemplary Equations | Key Variables & Parameters | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Tumor Growth | dT/dt = k_g * T (Exponential) [25] |

T: Tumor cell population; k_g: Growth rate constant; T_max: Carrying capacity |

Assumes unrestricted growth; often used for early, avascular tumor phases [25]. |

dT/dt = k_g * T * (1 - T/T_max) (Logistic) [25] |

Incorporates self-limiting growth due to environmental constraints like space and nutrients [25]. | ||

| Tumor-Immune Interaction (Predator-Prey) | dT/dt = f(T) - d_1 * I * T [25] |

I: Immune effector cell concentration (e.g., CTLs, NK cells); d_1: Immune-mediated kill rate |

Describes immune cells "preying" on tumor cells. f(T) represents intrinsic tumor growth [24] [25]. |

| Macrophage Polarization | dx_M1/dt = (a_s * x_Ts + a_m1 * x_Th1) * x_M1 * (1 - (x_M1 + x_M2)/β_M) - δ_m1 * x_M1 - k_12 * x_M1 * x_M2 + k_21 * x_M1 * x_M2 [24] |

x_M1/x_M2: M1/M2 macrophage density; k_12, k_21: Phenotype switching rates; β_M: Carrying capacity |

Models dynamic repolarization of macrophages between anti-tumor (M1) and pro-tumor (M2) phenotypes [24]. |

| Treatment & Resistance | dS/dt = f(S) - k_d * Exposure * S - m_1 * S + m_2 * R dR/dt = f(R) + m_1 * S - m_2 * R [25] |

S: Sensitive cell population; R: Resistant cell population; m_1, m_2: Mutation/ reversion rates |

Captures emergence of resistant subpopulations via spontaneous mutation and adaptation during treatment [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My ODE model of tumor-immune interactions becomes unstable, with immune cell populations dropping to zero or growing infinitely. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

Potential Cause 1: Poorly calibrated parameters. Unrealistic parameter values, especially for proliferation and death rates, can lead to non-physiological dynamics.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform a local or global sensitivity analysis (e.g., using Latin Hypercube Sampling and Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient) to identify which parameters most significantly impact model stability and outputs. Focus calibration efforts on these sensitive parameters [25].

- Literature Calibration: Rigorously search published experimental studies for realistic parameter ranges. For instance, the proliferation rate of Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes (CTLs) upon antigen encounter is a critical parameter that must be within a biologically plausible range [24].

- Steady-State Check: Ensure your model can maintain a non-trivial equilibrium (i.e., a state of tumor-immune dormancy) in the absence of treatment, reflecting the biological concept of immunosurveillance [24].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

Potential Cause 2: Missing a key biological feedback mechanism.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Model Auditing: Review your model against the latest literature. A common omission is the role of T regulatory cells (Tregs) which suppress effector immune responses. Adding a term for Treg-mediated suppression of CTLs or NK cells can stabilize models and prevent uncontrolled immune activation [24].

- Include Saturation: Replace simple linear interaction terms (e.g.,

d_1 * I * T) with saturated functional responses (e.g.,(d_1 * I * T) / (h + T)), wherehis a half-saturation constant. This represents the finite capacity of immune cells to kill targets, preventing infinite consumption of tumor cells [24] [25].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

FAQ 2: How can I extend a basic tumor growth ODE model to investigate optimal control theory for combination therapy scheduling?

- Solution: Develop a multi-compartment model with pharmacodynamic interactions.

- Methodology:

- Define Cell Populations: Model the tumor as a heterogeneous system. A minimal framework includes therapy-sensitive cells (

S), therapy-resistant cells (R), and a key immune effector population (I) [25] [26]. - Formulate the ODE System:

Here,

CandRadrepresent chemotherapy and radiotherapy doses,k_Candk_Iare kill rates,m_Sandm_Rare mutation rates, andr(C, Rad)is a treatment-dependent immune recruitment function [26] [27]. - Incorporate Drug Synergy: For combination chemotherapy, model the drug effect

k_Cnot as a constant, but as a function of multiple drug concentrations (u_1,u_2). A general framework can capture synergistic effects where the combined effect is greater than the sum of individual effects [26]. - Apply Optimal Control: Define an objective function (

J) to be minimized, for example:J = ∫ [ w_1*(S+R) + w_2*(C + Rad) ] dtThis balances tumor burden (S+R) against treatment toxicity (C+Rad) over time. Pontryagin's Maximum Principle can then be used to compute the optimal drug dosing schedulesC*(t)andRad*(t)that minimizeJ[26] [27].

- Define Cell Populations: Model the tumor as a heterogeneous system. A minimal framework includes therapy-sensitive cells (

- Methodology:

FAQ 3: When simulating combination therapy, my model predicts that maximum continuous dosing is always optimal. This contradicts clinical practice which uses intermittent schedules. Why?

- Potential Cause: The model lacks key toxicities and constraints.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Incorporate Toxicity Compartments: Add an ODE to track the health of a "dose-limiting" tissue (e.g., bone marrow-derived immune cells):

dL/dt = γ * L * (1 - L/L_max) - η_C * C * L - η_Rad * Rad * LImpose a state constraintL(t) > L_criticalthroughout the treatment window. This alone can force the optimal solution to become intermittent, allowingLto recover during drug holidays [27]. - Enforce Realistic Control Constraints: Define maximum tolerable doses per administration (

0 ≤ C(t) ≤ C_max,0 ≤ Rad(t) ≤ Rad_max). Optimal control solutions under these bounded constraints often naturally yield intermittent, or "bang-bang," scheduling to maximize tumor kill while staying within safety limits [26]. - Model Immune Exhaustion: Continuous high antigen load from rapid tumor killing can exhaust T cells. Adding an exhausted T cell compartment that loses cytotoxic function can make continuous dosing suboptimal, favoring schedules that allow immune recovery [24].

- Incorporate Toxicity Compartments: Add an ODE to track the health of a "dose-limiting" tissue (e.g., bone marrow-derived immune cells):

- Troubleshooting Guide:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for ODE Modeling and Validation

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Biological Correlate | Use Case in Modeling Context |

|---|---|---|

| ODE-toolbox (Python) [28] | Solver benchmarking and selection for dynamical systems. | Automates the choice of the most efficient numerical integrator for your specific ODE system, improving simulation speed and reliability. |

| Arbor [28] | High-performance library for multi-compartment cell simulations. | Enables detailed, tissue-scale spatial simulations that can be used to validate predictions from simpler, non-spatial ODE models. |

| BioExcel Building Blocks [28] | Workflows for molecular dynamics of proteins and ligands. | Useful for parameterizing drug-receptor binding kinetics (k_on, k_off) that can inform pharmacodynamic terms in the ODE model. |

| Positive Switched Systems [27] | A control-theoretic framework for scheduling different treatment modalities. | Used to formally determine the optimal switching sequence between radiotherapy and chemotherapy in combined treatment plans. |

| Multiplicative Control Framework [26] | A general ODE model for multi-drug actions on heterogeneous cell populations. | Provides a template for modeling synergistic drug interactions and calculating optimal pharmacodynamic dosing. |

| Sorivudine | Sorivudine, CAS:77181-69-2; 80434-16-8, MF:C11H13BrN2O6, MW:349.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tocainide | Tocainide, CAS:53984-26-2, MF:C11H16N2O, MW:192.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate key experimental and conceptual frameworks.

ODE Modeling and Optimal Control Workflow

Diagram 1: ODE Modeling and Control Workflow.

Key Signaling Pathways in Tumor-Immune Context

Diagram 2: Tumor-Immune Signaling Pathways.

Exploring Synergistic and Antagonistic Drug Interactions in Combined Modalities

Quantitative Foundation: Measuring Drug Interactions

Table 1: Key Models for Quantifying Drug Synergy and Antagonism [29] [30]

| Model Name | Type | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bliss Independence | Effect-based | ( S = E{A+B} - (EA + EB - EA \cdot E_B) ) | S > 0: Synergy; S < 0: Antagonism |

| Loewe Additivity | Dose-effect-based | ( 1 = \frac{DA}{D{x,A}} + \frac{DB}{D{x,B}} ) | CI < 1: Synergy; CI = 1: Additive; CI > 1: Antagonism |

| Combination Index (CI) | Dose-effect-based | ( CI = \frac{C{A,x}}{IC{x,A}} + \frac{C{B,x}}{IC{x,B}} ) | CI < 1: Synergy; CI = 1: Additive; CI > 1: Antagonism |

| HSA | Effect-based | ( S = E{A+B} - \max(EA, E_B) ) | S > 0: Synergy |

Table 2: Prevalence of Synergistic and Antagonistic Interactions in AML Cell Lines (Sample Data) [31]

| Drug Name | Mechanism/Target | Kasumi-1 | HL-60 | TF-1 | K-562 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enasidenib | IDH2 inhibitor | High Synergy | High Synergy | Medium Synergy | Low Synergy |

| Venetoclax | BCL-2 inhibitor | High Synergy | Medium Synergy | High Synergy | Antagonism |

| 6-Thioguanine | Purine analog | Antagonism | Antagonism | Antagonism | Antagonism |

| Cytarabine | Antimetabolite | Medium Synergy | Additive | Additive | Antagonism |

Experimental Protocols for Combination Screening

High-Throughput Cell Viability Assay for Drug Pair Screening

This protocol is designed to systematically test 105 drug pairs across multiple cell lines, as described in recent AML studies [31].

Workflow Overview

Detailed Methodology:

Cell Culture and Plating:

- Maintain AML cell lines (e.g., Kasumi-1, HL-60, TF-1) in appropriate media supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin [31].

- Plate cells in 384-well microtiter plates at optimized densities (e.g., 1,200-10,000 cells/well depending on the cell line) in a total volume of 60 µL per well [31].

- Incubate overnight at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

Drug Preparation and Dispensing:

- Dissolve test compounds in DMSO or aqueous solvent.

- Use an acoustic liquid handler (e.g., Echo555/655) to transfer compounds to 384-well plates [31].

- For combination assays, dose pairs of compounds in an 8x8 grid format, with concentrations determined by the pre-established ICâ‚…â‚€ for each compound.

Incubation and Viability Measurement:

- Incubate plates for 96 hours at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- Add CellTiter-Glo reagent (diluted 1:2) to each well, mix, and incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature [31].

- Measure luminescence using a multimodal plate reader.

Data Normalization and Analysis:

- Normalize raw luminescence values using the equation: (v{i,j} = \frac{y{i,j} - ni}{pi - ni}), where (y{i,j}) is the measured absorbance, (ni) is the median of negative controls (DMSO), and (pi) is the median of positive controls (e.g., 10 mM BFA) [31].

- Fit dose-response curves using a sigmoid model: (f(x, b{pos}, b{shape}) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-b{shape} * (x - b{pos})}}), where (x) is the logâ‚‚(drug concentration), (b{pos}) is ICâ‚…â‚€, and (b{shape}) is curve steepness [31].

- Calculate synergy scores using the Bliss Independence or other reference models.

Computational Prediction of Synergistic Combinations

Machine learning frameworks leverage diverse data types to predict drug interactions in silico, accelerating the discovery process [32] [30].

Computational Prediction Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

Data Collection and Annotation:

- Collect large-scale drug combination screening datasets (e.g., O'Neil dataset) [32].

- Annotate drug combinations with generic names, mechanisms of action (MoA), and known targets.

- Integrate multi-omics data for cell lines, including gene expression profiles, copy number variations, and mutation data [30].

Data Preprocessing:

- Perform normalization and standardization of omics data (e.g., log-transformation, batch-effect removal) [30].

- Partition the dataset into stratified training and test sets.

Model Building and Evaluation:

- Construct classification models (e.g., random forests, deep neural networks) to categorize combinations as synergistic, additive, or antagonistic [32].

- Build regression models to predict continuous synergy scores (e.g., CSS scores) [32].

- Evaluate models using cross-validation and metrics like Pearson correlation coefficient or AUC [30].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How do I determine if a drug interaction is truly synergistic and not just additive?

Answer: True synergy is confirmed when the combined effect is statistically greater than the expected effect under a reference model of non-interaction (e.g., Bliss Independence or Loewe Additivity) [29]. The choice of model is critical, as different models have different assumptions and mathematical frameworks [29]. It is essential to:

- Use Multiple Models: Cross-validate your findings with at least two different reference models (e.g., Bliss and CI) to ensure robustness [29].

- Statistical Testing: Perform statistical tests to confirm that the calculated synergy score is significantly different from zero (for Bliss) or that the CI is significantly less than 1 [31].

- Dose-Range Dependence: Be aware that a pair might be synergistic at certain dose ratios and antagonistic at others. Always test a full matrix of concentrations [31].

FAQ 2: Why are drug interactions not conserved across different cancer cell lines?

Answer: The context-specific nature of drug interactions is a major challenge. A pair synergistic in one cell line may be antagonistic in another due to differences in [31]:

- Genetic Mutations: Specific driver mutations (e.g., IDH2, TP53) can drastically alter pathway dependencies and drug responses. A single mutation can turn a synergistic interaction into an antagonistic one [31].

- Pathway Activity: Variations in the activity of signaling pathways (e.g., MAPK, PI3K) between cell lines influence how drugs interact [33].

- Tumor Microenvironment: Factors like hypoxia and stromal interactions, though less captured in 2D cultures, contribute to heterogeneous responses [29].

Troubleshooting Table: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in replicate synergy scores. | Inconsistent cell seeding density or drug dispensing. | Standardize cell counting and use automated liquid handlers for drug transfer [31]. |

| A known synergistic pair shows no effect. | Drug concentrations are below effective levels or incubation time is too short. | Re-determine ICâ‚…â‚€ values for your specific cell line and ensure a sufficient incubation period (e.g., 96 hours) [31]. |

| Computational model fails to predict known synergies. | Lack of relevant biological features in the training data for the specific cancer type. | Incorporate more context-specific data, such as cell line-specific mutational status or pathway activity, into the model [32] [30]. |

| Antagonism is consistently observed. | Overlapping toxicities or pharmacokinetic interference (e.g., one drug affects the metabolism of the other). | Review the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profiles of the drugs. Consider adjusting the dosing schedule (sequential vs. simultaneous) [34]. |

FAQ 3: How can Optimal Control Theory (OCT) be integrated with synergy data?

Answer: OCT provides a mathematical framework to design personalized treatment schedules that leverage synergy while minimizing toxicity [5] [6] [3]. The process involves:

- Model Formulation: The patient's tumor dynamics are described as a dynamical system, often using differential equations. The state variables ((x(t))) represent tumor cell populations, and the control inputs ((u(t))) represent drug doses or their effects [3].

- Incorporating Synergy: The model's equations are structured so that the inhibitory effect on tumor growth from a synergistic drug pair is greater than the sum of individual effects, as quantified by your experimental synergy scores [33].

- Defining the Objective: A performance measure ((J)) is formulated, typically aiming to minimize the tumor cell count at the end of the treatment period ((t_f)) while constraining the cumulative toxicity to healthy tissues [6] [3].

- Solving the Control Problem: Optimization algorithms (e.g., IPOPT, SDRE) are used to compute the optimal drug administration schedule—the sequence and timing of doses that maximize efficacy and minimize side effects [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Drug Combination Studies [32] [34] [33]

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| AML Cell Line Panel (e.g., Kasumi-1, HL-60, TF-1) | In vitro models representing genetic heterogeneity of AML. | Select cell lines with diverse genetic backgrounds (e.g., different mutations, translocations) to assess context-specificity of interactions [31]. |

| Targeted Inhibitors (e.g., Venetoclax, Enasidenib, kinase inhibitors) | Drugs targeting specific proteins or pathways crucial for cancer cell survival. | Purity and stability are critical. Prepare fresh stock solutions in recommended solvents (DMSO) and store as per manufacturer's guidelines [32] [31]. |

| CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay | Quantifies ATP levels as a marker of metabolically active (viable) cells. | Offers high sensitivity and a wide dynamic range for 384-well plate formats. Ensure reagent is equilibrated to room temperature before use [31]. |

| Acoustic Liquid Handler (e.g., Echo 555/655) | Non-contact dispenser for highly precise and miniaturized drug transfers in DMSO. | Essential for creating accurate 8x8 dose-response matrices while minimizing solvent volume, which can affect cell health [31]. |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors (e.g., Omeprazole) | Used to study pharmacokinetic DDIs related to altered gastric pH. | Can reduce the solubility and bioavailability of concomitant oral TKIs (e.g., Pazopanib, Erlotinib). Separate administration times may be required [34]. |

| CYP3A4 Inhibitors/Inducers (e.g., Ketoconazole, Rifampicin) | Tools to investigate metabolic drug-drug interactions. | Many anticancer drugs (e.g., Ibrutinib) are CYP3A4 substrates. Coadministration can lead to significant changes in systemic exposure and toxicity [34]. |

| Pan-Cancer Pathway Model | Large-scale ODE model simulating the effect of 7 targeted agents on 1228 molecular species [33]. | Used for in silico prediction of combination effects and optimization of therapy schedules before experimental validation [33]. |

| Excisanin B | Excisanin B, MF:C22H32O6, MW:392.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Hydroxychimaphilin | 3-Hydroxychimaphilin, MF:C12H10O3, MW:202.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Advances: Applying OCT to Pan-Cancer Models and Personalized Regimens

Constructing Large-Scale Mechanistic Models of Signaling Pathways for In Silico Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary software tools available for constructing and simulating large-scale mechanistic models? Multiple specialized software tools are available. The Julia programming language is used for generating synthetic signaling networks and has gained traction in the systems biology community [35]. Python-based pipelines are employed for creating models that are high-performance and cloud-computing ready, converting structured text files into the standard SBML format [36]. R/Bioconductor packages, such as the HiPathia package, implement algorithms for interpreting transcriptomic data within mechanistic models [37]. Rule-based modeling software like BioNetGen and PySB can also be used to define reaction patterns [36].

How can I ensure my model is reusable and interoperable? Adhering to community standards is crucial. Using the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) is a gold-standard practice for ensuring model portability between different software tools [36]. Providing comprehensive metadata and annotations for all model components (e.g., using ENSEMBL or HGNC identifiers) is essential for findability and reusability [36]. Furthermore, using simple, structured text files to define model specifics makes the model easy to alter and process programmatically [36].

My model simulations are computationally expensive. What are my options? For large-scale models, local machine simulation can be prohibitive. Leveraging High Performance Computing (HPC) or Cloud Computing (CC) platforms is recommended for tasks like parameter estimation or multiple single-cell simulations [36]. Using simulation packages specifically designed for efficiency, such as AMICI for Python, can significantly reduce CPU time [36].

What is a reliable method to validate a novel network inference or parameter fitting algorithm? Using synthetic signaling networks as ground truth models is a powerful validation strategy. You can generate artificial networks with known topology and parameters using tools like the provided Julia script [35]. These networks can then be used to produce synthetic "experimental" data, providing a known target against which to test your algorithm's performance [35].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Poor Model Performance or Inaccurate Predictions

This can stem from several issues, including overfitting, non-identifiable parameters, or an incorrect network topology.

- Potential Cause 1: Overfitting and parameter non-identifiability due to a large number of state variables and parameters and limited calibration data [35].

- Potential Cause 2: The model topology lacks key biological features found in real signaling pathways, such as feedback loops [35].

- Solution: Compare the topology of your generated network against established models from databases like the BioModels Database. Use metrics like reaction degree and reaction distance to assess topological similarity [35].

- Potential Cause 3: Missing key cellular contexts, such as sequestration effects in phosphorylation cycles, which can significantly alter network behavior [35].

- Solution: Review model reaction rules to include critical processes like sequestration, especially when substrates and catalytic proteins (e.g., phosphatases) are present at comparable concentrations [35].

Problem 2: Model is Difficult to Simulate, Share, or Extend

This often results from using non-standard or custom-coded formats that are not easily portable.

- Potential Cause: Use of a custom-structured, non-standard model format that is not supported by mainstream simulation software [36].

Problem 3: Difficulty Integrating Transcriptomic Data for Functional Predictions

It can be challenging to connect gene expression levels to downstream functional activities like cell proliferation or death.

- Potential Cause: Treating the pathway as a single multifunctional entity rather than decomposing it into specific functional circuits [37].

- Solution: Deconstruct pathways into signaling circuits—elementary functional entities that connect receptors to effector proteins. Use an algorithm like HiPathia to simulate signal propagation through these circuits based on protein activity levels (e.g., from gene expression data) to generate functional profiles [37].

Experimental Protocols for Key Tasks

Protocol 1: Generating a Synthetic Signaling Network for Algorithm Testing

Purpose: To create a realistic, artificial signaling network with known topology and parameters that can serve as ground truth for validating network inference and parameter fitting algorithms [35].

Methodology:

- Define Reaction Motifs: Start with a list of core signaling unit processes. These typically include [35]:

- Catalyzed transformations

- Binding and unbinding reactions (following mass-action kinetics)

- Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycles (both single and double)

- Network Generation: Use a computational script (e.g., the provided Julia script) to randomly assemble these motifs into a larger network [35].

- Topological Validation: Calculate the reaction degree and reaction distance distributions of your synthetic network. Compare these distributions to those of curated signaling models from the BioModels Database to assess topological realism [35].

- Dynamic Validation: Compare the behavioral dynamics (e.g., steady states, oscillations) of your synthetic network with those of BioModels to ensure dynamic similarities [35].

Table: Core Reaction Motifs for Synthetic Network Generation

| Motif Type | Description | Kinetic Law |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyzed Transformation | Enzyme-catalyzed conversion of a substrate | Reversible Michaelis-Menten |

| Binding/Unbinding | Formation and dissociation of protein complexes | Mass-action |

| Phosphorylation Cycle | Addition/removal of a phosphate group by kinase/phosphatase | Reversible Michaelis-Menten |

Workflow for generating and validating a synthetic signaling network.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Large-Scale Model for Single-Cell Simulations

Purpose: To build a large-scale, mechanistic model (e.g., encompassing proliferation and death signaling) that is scalable, standards-compliant, and ready for single-cell level simulations and data integration [36].

Methodology:

- Define Model in Structured Files: Create a set of simple, structured text files that define the model's genes, species, reactions, stoichiometry, compartments, and parameters. This approach minimizes coding and allows for easy alteration [36].

- Convert to Standard Format: Process these input files using a script (e.g., a Jupyter notebook) to create a human-readable Antimony file. Then, convert the Antimony file into a standard SBML model file [36].

- Simulate the Model: Use SBML-compatible Python packages like AMICI for efficient deterministic simulation of large-scale models [36]. For single-cell simulations, incorporate a submodule for stochastic gene expression [36].

- Scale Computations: For large tasks (e.g., parameter estimation across many single cells), deploy the simulation pipeline on High Performance Computing (HPC) or Cloud Computing (CC) platforms like Kubernetes [36].

Table: Key Files for Large-Scale Model Construction

| File Type | Contents | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Gene List | Modeled genes with identifiers | Defines genetic components |

| Reaction File | List of all biochemical reactions | Specifies network interactions |

| Stoichiometry File | Stoichiometric coefficients for reactions | Defines mass balance |

| Parameter File | Kinetic parameters and initial conditions | Sets model dynamics |

| Compartment File | Cellular locations (e.g., cytosol, nucleus) | Provides spatial context |

Pipeline for constructing and simulating a large-scale, standards-compliant model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Julia Scripts [35] | Generate synthetic signaling networks for algorithm validation. | Creates networks with topological & dynamic similarity to BioModels. |

| SPARCED Pipeline [36] | Python-based creation & simulation of large-scale single-cell models. | Input text files, outputs SBML via Antimony, HPC/CC ready. |

| HiPathia [37] | R package for mechanistic modeling of signaling pathways from transcriptomic data. | Simulates signal transduction through functional circuits; estimates mutation/drug effects. |

| BioModels Database | Repository of curated, published mathematical models of biological systems. | Source of realistic models for topological and dynamic comparison [35]. |

| AMICI [36] | Python/C++ package for simulation of differential equation models. | High-performance simulation of SBML models; fast gradient computation. |

| Antimony [36] | Human-readable language for describing biochemical models. | Facilitates the creation of complex SBML models through a simplified text format. |

| Spinorhamnoside | Spinorhamnoside, MF:C34H40O15, MW:688.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4,5-Diepipsidial A | 4,5-Diepipsidial A, MF:C30H34O5, MW:474.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary goal of applying optimal control to cancer combination therapy? The primary goal is to compute a control function (e.g., a drug dosing schedule) that optimizes a performance metric related to the state of the disease (e.g., tumor cell count) and the control effort (e.g., drug dosage and associated toxicity). This involves minimizing a cost functional that balances treatment benefits against side effects and dosage costs [38] [39].

FAQ 2: What are the key components of a standard optimal control problem in this context? A standard problem formulation includes:

- A dynamical system: A set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that model the evolution of the disease (e.g., cell populations) under the influence of therapies [26] [38].

- A cost functional: A mathematical expression that quantifies the treatment goal, typically an integral of a "running cost" over time, sometimes with a terminal cost [39].

- Constraints: These can include initial conditions, upper and lower limits on drug doses, and state constraints [38] [39].

FAQ 3: My model is very complex and non-linear. Can optimal control still be applied? Yes. While analytical solutions (like those provided by Pontryagin's Maximum Principle) may be intractable for highly complex models, numerical optimal control techniques are designed for this purpose. These methods discretize the continuous-time problem into a finite-dimensional optimization problem that can be solved with nonlinear programming solvers [39] [40].

FAQ 4: How do I account for patient-reported toxicity and quality of life in the optimal control framework? Toxicity and quality of life can be incorporated into the cost functional. For instance, the running cost ( L(x,u,t) ) can include terms that penalize high drug concentrations (representing toxicity) and terms that penalize a low quality of life or the occurrence of specific adverse events, often quantified using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [41] [42]. This creates a multi-objective optimization where the goal is to find a Pareto-optimal balance between efficacy and tolerability [41].

FAQ 5: What is the difference between a finite-horizon and an infinite-horizon optimal control problem?

- Finite-horizon problems consider a fixed treatment end time ( T ). The cost functional integrates cost from time 0 to ( T ) and may include a terminal cost ( \Phi(x(T)) ) that penalizes the final state [39].

- Infinite-horizon problems consider an infinite time period, which can be ill-posed. They are often made tractable by adding a discount factor that decays over time, ensuring the cost integral remains finite [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: ODE Solver is Slow or Fails to Converge

Problem: The numerical simulation of your model's ODEs is unstable, slow, or produces nonsensical results, preventing the optimal control algorithm from finding a solution.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Step 1: Check for Stiffness

- Symptoms: The ODE solver (particularly non-stiff solvers like

ode45) takes an extremely long time or takes very small time steps. - Solution: Stiffness occurs when there is a drastic difference in scaling or time scales within the problem [43]. Switch to a solver designed for stiff systems, such as

ode15s[43].

- Symptoms: The ODE solver (particularly non-stiff solvers like

Step 2: Verify Your Model Equations and Parameters

- Symptoms: The solver fails entirely or states become NaN (not a number).

- Solution:

- Double-check the equations for typos and dimensional consistency.

- Ensure all parameter values are physically plausible and in the correct units.

- Simplify the model if possible. Using linear growth rates, for example, can make the optimal control problem more analytically tractable and numerically stable [26].

Step 3: Choose the Right Solver Refer to the following table for guidance on selecting an ODE solver in MATLAB [43].

| Solver | Problem Type | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

ode45 |

Nonstiff | This should be your first choice for most problems. |

ode23 |

Nonstiff | Can be more efficient than ode45 at problems with crude tolerances or moderate stiffness. |

ode113 |

Nonstiff | Can be more efficient than ode45 at problems with stringent error tolerances. |

ode15s |

Stiff | Use when ode45 fails or is slow and you suspect the problem is stiff. Also for DAEs of index-1. |

ode23s |

Stiff | Can be more efficient than ode15s at problems with crude error tolerances. |

ode23t |

Moderately Stiff | Use for moderately stiff problems where a solution without numerical damping is needed. |

Issue 2: The Optimized Dosing Schedule is Not Clinically Feasible

Problem: The optimal control solution suggests a highly variable, continuous dosing regimen that cannot be implemented in a real-world clinical setting (e.g., continuous IV infusion with rapidly changing rates).

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Step 1: Reformulate the Problem with Clinical Constraints

- The unconstrained optimal solution is often theoretically ideal but impractical. You must explicitly add constraints to your optimization problem [38].

- Discrete Dosing: Formulate the problem in discrete time, where controls are constant over a fixed period (e.g., 24 hours), representing a daily dose [39].

- Dose Levels: Constrain the control

u(t)to a finite set of allowed doses (e.g., 0 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg). - Dose Timing: Fix the times at which doses can be administered.

Step 2: Use a Discrete-Time Formulation Discretize your continuous-time model. The discrete-time optimal control problem seeks a sequence of states ( (x1, \ldots, xN) ) and controls ( (u0, \ldots, u{N-1}) ) that minimize: [ J(\mathbf{x},\mathbf{u}) = \sum{i=0}^{N-1} L(xi,ui,i) + \Phi(xN) ] subject to ( x{i+1} = g(xi, u_i) ), where

gis a simulation function (e.g., from Euler integration) that approximates the continuous dynamics [39].

Issue 3: Difficulty Balancing Multiple, Conflicting Objectives

Problem: You need to minimize tumor size, minimize drug toxicity, and minimize the total drug used, but these goals are in conflict. Manually tuning the weights in the cost functional is time-consuming and unsatisfactory.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Step 1: Adopt a Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) Framework

- Instead of combining all objectives into a single cost functional with weights, treat them as separate objectives [41].

- The goal of MOO is not to find a single "best" solution but to find a set of Pareto-optimal solutions. A solution is Pareto-optimal if no objective can be improved without worsening another [41].

Step 2: Compute and Analyze the Pareto Front

- Use MOO algorithms (e.g., evolutionary algorithms) to compute the Pareto front.

- This front, often visualized as a surface in objective space, provides a clear picture of the trade-offs between, for example, cancer cell count and side effects [41].

- A clinician can then examine the Pareto front and select a treatment regimen based on a patient's specific tolerance for side effects versus aggressiveness of treatment.

Issue 4: High-Dimensional State Space Leads to Intractable Computation

Problem: Your model has many cell populations and drug interactions, leading to a high-dimensional state space. The optimal control problem becomes computationally too expensive to solve.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Step 1: Model Reduction

- Create a "semi-mechanistic" or "fit-for-purpose" model that includes only the key populations and interactions necessary to answer your specific question [38]. This reduces the state dimension

n. - The general framework for heterogeneous cell populations can be a template for building a simpler, tailored model [26].

- Create a "semi-mechanistic" or "fit-for-purpose" model that includes only the key populations and interactions necessary to answer your specific question [38]. This reduces the state dimension

Step 2: Efficient Discretization and solver choice

- Carefully choose the number of discretization time points

N. A finer grid is more accurate but much more costly. - Investigate solvers that are efficient for large-scale nonlinear optimization problems, such as Interior Point OPTimizer (IPOPT), which has been used successfully in cancer treatment optimization [44].

- Carefully choose the number of discretization time points

Experimental Protocols & Reference Tables

Table 1: Key Parameters for a Sample Optimal Control Problem in CML

This table summarizes parameters from a published model for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), which includes quiescent and proliferating leukemic cells and an immune effector cell population [38].

| Parameter / Variable | Description | Value / Unit |

|---|---|---|

| ( x_1 ) | Quiescent leukemic cell population | Cells |

| ( x_2 ) | Proliferating leukemic cell population | Cells |

| ( x_3 ) | Immune effector cell level | Cells |

| ( u_1 ) | Dose of targeted therapy 1 (e.g., Imatinib) | mg |

| ( u_2 ) | Dose of targeted therapy 2 | mg |

| ( u_3 ) | Dose of immunotherapy | mg |

| ( L(x,u) ) | Running cost (( = w1x1 + w2x2 + w3u1^2 + w4u2^2 + w5u3^2 )) | Cost units |

| ( w1, w2 ) | Weights on tumor cell populations | 1/(cell²) |

| ( w3, w4, w_5 ) | Weights on drug usage (penalizing toxicity/cost) | 1/(mg²) |

Table 2: Comparison of Optimal Control Techniques for a Sample Tumor Model

This table compares different control strategies applied to a malignant tumor model, demonstrating the performance of various numerical techniques [44].

| Technique | Description | Cost Value Achieved |

|---|---|---|

| IPOPT (Interior Point Optimizer) | An open-source tool for large-scale nonlinear optimization. | 52.3573 |

| SDRE (State-Dependent Riccati Equation) | Adapts linear control methods for nonlinear systems. | 52.4240 |

| ASRE (Approximate Sequence Riccati Equation) | A globally optimal feedback control approach for nonlinear systems. | 52.4240 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential components of the modeling and optimization "toolkit" for implementing optimal control in cancer therapy.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) System | The core semi-mechanistic model describing the dynamics of cancer cell populations, immune cells, and drug interactions [26] [38]. |

ODE Solver (e.g., ode45, ode15s) |

A numerical routine for simulating the forward dynamics of the model given a control input. Essential for evaluating the cost functional [43]. |

| Nonlinear Programming (NLP) Solver (e.g., IPOPT) | The computational engine that performs the actual optimization, finding the control sequence that minimizes the cost functional subject to constraints [44] [39]. |

| Cost Functional Weights (( w_i )) | Tuning parameters that balance the relative importance of different objectives (e.g., tumor reduction vs. toxicity) in the overall goal [41] [39]. |

| Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) | Standardized questionnaires (e.g., PRO-CTCAE) used to quantify the patient's perspective on treatment toxicity and quality of life, providing data for the toxicity terms in the cost functional [42]. |

| Orpinolide | Orpinolide, MF:C30H45NO4, MW:483.7 g/mol |

| Armeniaspirol B | Armeniaspirol B, MF:C18H19Cl2NO4, MW:384.2 g/mol |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Optimal Control Workflow

Multi-Objective Optimization Trade-offs

This section addresses fundamental questions about the CMA-ES algorithm and its relevance to computational research in cancer therapy optimization.

What is CMA-ES and why is it suitable for non-convex optimization in cancer therapy design?

The Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) is a stochastic, derivative-free numerical optimization method for difficult non-linear, non-convex black-box problems in continuous domain [45] [46]. It evolves a population of candidate solutions by adapting a multivariate normal distribution, effectively learning a second-order model of the objective function similar to approximating an inverse Hessian matrix [45]. This makes it particularly effective for problems where gradient-based methods fail due to rugged search landscapes containing discontinuities, sharp ridges, noise, or local optima [45].

In cancer therapy optimization, CMA-ES is valuable because it can handle complex, non-convex objective functions that arise when balancing multiple treatment goals such as minimizing tumor proliferation while controlling drug dosage to reduce side effects [33]. The algorithm's invariance properties make it robust across different problem formulations, and it requires minimal parameter tuning from users [45].

How does CMA-ES differ from traditional gradient-based optimization methods?

citation:10

| Feature | CMA-ES | Gradient-Based Methods (e.g., BFGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Derivative Requirement | No gradients required | Requires gradient information |

| Problem Types | Effective on non-convex, noisy, discontinuous problems | Best for smooth, convex problems |

| Convergence Speed | Slower on purely convex-quadratic functions | Typically 10-30x faster on convex-quadratic functions |

| Parameter Tuning | Minimal tuning required (mostly automated) | Often requires careful parameter adjustment |

| Solution Sampling | Population-based sampling | Point-to-point optimization |

What are the key internal state variables maintained by CMA-ES during optimization?

The CMA-ES algorithm maintains several critical state variables throughout the optimization process [46]:

- Mean vector ($m_k$): Represents the current favorite solution point in the search space

- Step-size ($\sigma_k$): Controls the overall scale of the search distribution

- Covariance matrix ($C_k$): Encodes the pairwise relationships between variables and the orientation of the search distribution

- Evolution paths ($p\sigma$, $pc$): Track the correlation between consecutive steps and enable cumulative step-size adaptation

These variables are updated iteratively based on the success of sampled candidate solutions, allowing the algorithm to learn effective search directions and scales without explicit gradient information [46].

Implementation and Configuration

This section provides practical guidance for implementing CMA-ES in scientific computing environments, particularly for cancer therapy optimization problems.

How do I properly configure CMA-ES parameters for drug dosage optimization problems?

For cancer therapy optimization where the search space typically involves drug concentration parameters, we recommend the following configuration approach based on the experimental setup described in [33]:

- Initialization: Set the initial mean vector $m_0$ to the center of your search space or based on prior knowledge of effective drug combinations

- Step-size: Set the initial step-size $\sigma_0$ to approximately 1/3 to 1/6 of the parameter range to ensure effective exploration

- Population size: For problems with 5-20 drug parameters, use population sizes ($\lambda$) between 20-100 individuals

- Stopping criteria: Implement termination based on fitness stagnation, maximum evaluations, or convergence thresholds

The following table summarizes key parameter settings for different problem scales in therapy optimization:

citation:1] [47][citation:3