Optimal Control Methods for Optimizing Combination Drug Regimens: From Mathematical Models to Clinical Translation

Combination therapies are a cornerstone of modern treatment for complex diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders, and Alzheimer's, but optimizing their dosing and scheduling presents significant challenges.

Optimal Control Methods for Optimizing Combination Drug Regimens: From Mathematical Models to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Combination therapies are a cornerstone of modern treatment for complex diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders, and Alzheimer's, but optimizing their dosing and scheduling presents significant challenges. This article explores the application of optimal control theory as a powerful, quantitative framework to design effective multi-drug regimens. It covers the foundational principles of modeling heterogeneous cell populations and drug synergies, delves into methodological advances like data-driven robust optimization and Pontryagin's principle, and addresses critical hurdles such as drug resistance, off-target effects, and clinical heterogeneity. By comparing model-based approaches and discussing validation strategies, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of how to balance therapeutic efficacy with toxicity constraints, ultimately guiding the development of safer, more personalized treatment protocols.

The Foundation of Control: Modeling Cell Populations and Drug Interactions

The Critical Need for Combination Therapies in Complex Diseases

Combination therapeutics, defined as pharmacological interventions using several drugs that interact with multiple disease targets, have become a mainstay in treating complex diseases [1]. Complex diseases, including cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions, are driven by intricate molecular networks and biological redundancies that render single-drug therapies often insufficient [1]. The limitations of monotherapy are particularly evident in oncology, where tumor heterogeneity, drug resistance, and interconnected pathological pathways necessitate multi-target approaches [2] [3].

Combination regimens offer numerous clinical advantages over single-agent treatment, including increased efficacy through targeting parallel disease pathways, reduced likelihood of drug resistance, decreased dosage requirements for individual components, and potentially reduced side effects through lower individual drug exposures [2] [1]. The development of optimal combination regimens, however, presents significant challenges, requiring careful consideration of drug selection, dosing schedules, sequencing, and interaction effects [4]. This application note explores computational and mathematical frameworks for addressing these challenges, with a focus on optimal control methods for regimen optimization.

Mathematical Foundations for Optimizing Combination Therapies

Optimal Control Theory in Therapeutic Optimization

Optimal control theory provides a powerful mathematical framework for determining the best possible administration of combination therapies to achieve specific therapeutic goals. This approach involves optimizing a real-world quantity (objective functional) represented by a mathematical model of the disease and treatment dynamics [5]. The general process for applying optimal control to combination therapy optimization includes:

- Disease Model Development: Creating a semi-mechanistic mathematical model incorporating disease dynamics and therapeutic effects

- Objective Quantification: Defining treatment goals mathematically, typically maximizing efficacy while minimizing toxicity

- Parameter Estimation: Determining model parameter values from individual or aggregate patient data

- Solution Computation: Calculating the optimal control solution through numerical methods

- Validation: Comparing predicted optimal regimens against standard treatments [5]

This methodology differs from quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) in its focus on optimization and generally involves smaller, fit-for-purpose models that are more amenable to numerical optimization techniques [5].

Modeling Frameworks for Heterogeneous Cell Populations

Cell heterogeneity plays a crucial role in treatment response, particularly in oncology where it associates with poor prognosis [3]. A general ordinary differential equation (ODE) framework for multi-drug actions on discrete cell populations can be expressed as:

dx/dt = F(x, u)

Where x ∈ â„^n represents cell counts of different populations and u ∈ â„^m represents the pharmacodynamic effects of different drugs [3]. This framework captures three key phenomena:

- Cell proliferation and death (assuming linear growth rates for mathematical tractability)

- Spontaneous conversion between cell types (potentially mediated by drug treatment)

- Drug-drug interactions producing synergistic effects [3]

Table 1: Key Components of Mathematical Optimization Frameworks

| Component | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Mechanistic Models | Fit-for-purpose models including key populations and "net effects" | Multiple myeloma model incorporating immune dynamics and three therapies [6] |

| Objective Functional | Mathematical expression combining efficacy benefits and toxicity penalties | CML treatment optimization minimizing leukemic populations and drug amounts [5] |

| Constrained Optimization | Incorporation of clinical feasibility constraints | Approximation methods producing near-optimal, clinically feasible regimens [6] |

| Interaction Parameters | Quantification of synergistic, additive, or antagonistic drug effects | Universal Response Surface Approach (URSA) for tuberculosis drug combinations [7] |

Computational Protocols for Personalized Combination Therapy

BMC3PM Bioinformatics Protocol for Personalized Medicine

The Bioinformatics Multidrug Combination Protocol for Personalized Medicine (BMC3PM) provides a methodological interface between drug repurposing and combination therapy in cancer treatment [8]. This protocol enables extraction of personalized drug combinations from hundreds of drugs and thousands of potential combinations based on individual gene expression profiles.

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

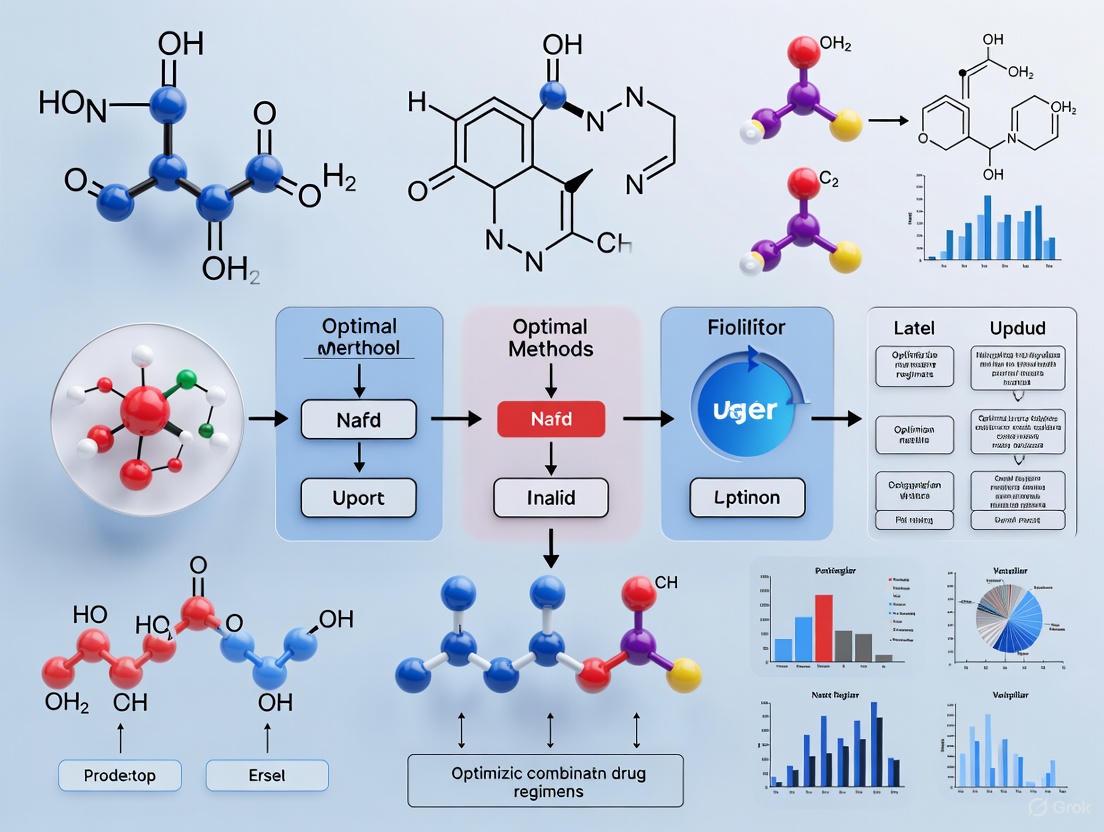

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive BMC3PM workflow for deriving personalized combination therapies:

BMC3PM Personalized Combination Therapy Workflow

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Obtain whole-genome expression profiles from patient and healthy control populations [8]

- Perform background correction and normalization using frozen robust multiarray analysis (fRMA)

- Remove batch effects and unwanted variation using combat function

Step 2: Deregulated Gene Identification

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using the Limma package in R

- Classify genes as upregulated (URGs; LogFC > 0.45) or downregulated (DRGs; LogFC < -0.45)

- Calculate health intervals for each gene representing normal expression ranges in healthy controls

Step 3: Individual Pattern of Perturbed Gene Expression (IPPGE)

- Compare individual patient gene expression profiles with health intervals

- Identify individual dysregulated genes falling outside health intervals

- Generate IPPGE representing the unique disease signature for each patient

Step 4: Drug Combination Algorithm

- Create Primary Health Matrix (PHM) synchronizing IPPGE with drug signatures from databases like CMAP

- Implement Drug Combination (DC) algorithm to select optimal drug combinations

- Prioritize drugs that move the most genes into health intervals with fewest gene expression interactions among drugs (GEIADs)

Step 5: Validation and Network Analysis

- Reconstruct directed differential network using biological pathway data

- Map drug combination targets to differential signaling network

- Predict effects on gene expression and pathway regulation [8]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Combination Therapy Development

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Data | Whole-genome expression profiles from patient and healthy populations | BMC3PM protocol for identifying individual patterns of perturbed gene expression [8] |

| CMAP Database | Drug perturbation gene expression profiles | Matching patient IPPGE with drug signatures for repurposing opportunities [8] |

| KEGG Pathway Database | Repository of biological pathways | Reconstruction of directed networks for target identification [8] |

| Hollow Fiber Infection Model (HFIM) | In vitro system simulating in vivo pharmacokinetics | Evaluation of anti-infective combinations and resistance suppression [7] |

| Mathematical Optimization Software | Differential equation solvers and optimization algorithms | Implementation of optimal control theory for regimen optimization [5] |

Advanced Modeling Techniques for Combination Therapy Optimization

Correlated Drug Action (CDA) Model

The Correlated Drug Action (CDA) model provides a baseline framework for understanding combination therapy effects in both cell cultures and patient populations. CDA assumes that drug efficacies in combinations may be correlated, generalizing other proposed models such as Bliss response-additivity and the dose equivalence principle [9]. The model introduces:

- Temporal CDA (tCDA): Applied to clinical trial data to identify synergistic combinations explainable through monotherapy effects

- Dose CDA (dCDA): Used with cell line data to assess combinations across different concentration levels

- Excess over CDA (EOCDA): A novel metric for identifying potentially synergistic combinations in cell culture [9]

Universal Response Surface Approach (URSA) for Drug Interactions

The Universal Response Surface Approach provides a mathematically rigorous method for determining drug interactions (synergy, additivity, antagonism) in combination therapies. Originally developed in oncology, this approach has been extended to incorporate a priori drug-resistant subpopulations, which is particularly valuable for anti-infective therapies [7].

The mathematical framework involves:

- Modeling concentration-time profiles for each agent

- Describing drug exposure impact on total bacterial populations, including resistant subpopulations

- Estimating interaction parameters (α) to quantify synergy, additivity, or antagonism

- Performing Monte Carlo simulations to identify optimal dosing for maximal bacterial kill while suppressing resistance [7]

Nanotechnology-Enabled Combination Therapy Delivery

Multifunctional nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems represent a cutting-edge approach to overcoming limitations of conventional combination therapy. These systems provide:

- Simultaneous or sequential delivery of multiple therapeutic agents

- Improved drug solubility, stability, and targeted delivery

- Extended drug release profiles and reduced off-target effects

- Ability to overcome biological barriers and enhance intracellular delivery [2]

Notable examples include Vyxeos, a liposomal formulation co-loading daunorubicin and cytarabine approved for acute myeloid leukemia, which demonstrates more consistent pharmacokinetics between the two drugs compared to free combination [2].

Quantitative Framework for Combination Therapy Assessment

Pharmacodynamic Interaction Models

Characterizing combination drug effects requires robust quantitative frameworks. The General Pharmacodynamic Interaction (GPDI) model can quantify interactions through maximal effects and potency parameters [2]. For instance, application of GPDI demonstrated that the docetaxel-SCO-101 combination produced a 60% increase in potency against drug-resistant MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cells compared to docetaxel alone [2].

Combination Effect Assessment Models

Table 3: Mathematical Models for Assessing Combination Therapy Effects

| Model | Principle | Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Single Agent (HSA) | Compares combination effect to the best single agent | CI = max(EA, EB)/E_AB | CI > 1 indicates positive combination |

| Response Additivity | Assumes linear dose-effect relationships | CI = (EA + EB)/E_AB | CI > 1 suggests synergy |

| Bliss Independence | Assumes drugs act independently on distinct sites | CI = (EA + EB - EAEB)/E_AB | CI < 1 indicates synergy [2] |

| Universal Response Surface | Parametric approach incorporating resistant subpopulations | System of differential equations with interaction terms | Enables Monte Carlo simulation for population optimization [7] |

Optimal Control in Clinical Translation

The implementation of optimal control theory for combination regimen optimization faces both challenges and opportunities in clinical translation:

Challenges:

- Limited readily accessible data for characterizing patient-specific parameters

- Lack of practical theoretical formalisms for computing optimal regimens for individual patients

- Clinical feasibility of highly variable dosing regimens predicted by mathematical optimization [4]

Opportunities:

- Integration with quantitative imaging data for patient-specific tumor characterization

- Multiscale modeling incorporating additional layers of patient-specific data

- Development of constrained optimization approaches producing clinically feasible regimens [4]

The following diagram illustrates the mathematical optimization framework for combination therapies:

Mathematical Optimization Framework

The critical need for combination therapies in complex diseases continues to drive the development of sophisticated computational and mathematical approaches for regimen optimization. Optimal control theory, bioinformatics protocols like BMC3PM, and quantitative assessment frameworks provide powerful methodologies for addressing the challenges of drug selection, dosing optimization, and personalization. As these approaches continue to evolve and integrate with advancing technologies such as nanoparticle-mediated delivery and multiscale modeling, they hold significant promise for improving therapeutic outcomes across a spectrum of complex diseases.

Optimal control theory is a branch of mathematics designed to optimize solutions for dynamical systems by finding the best possible way to steer a process towards a desired objective [5] [4]. In pharmacodynamics, which studies the biochemical and physiological effects of drugs, optimal control provides a rigorous framework to personalize therapeutic plans, particularly for complex combination regimens in diseases like cancer, HIV, and multiple myeloma [5] [10]. The core principle involves using mathematical models of disease and drug effects to compute time-varying drug administration schedules that maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects and toxicity [5]. This approach is especially valuable when the number of potential drug combinations and dosing schedules is too vast to test empirically, even in preclinical studies [5].

Theoretical Foundations

The application of optimal control to pharmacodynamics is built upon a structured process. The foundational steps are visualized in the following workflow:

Key Mathematical Components

The optimization process relies on several mathematical components:

- Dynamical System Model: A set of differential equations representing the key biological populations (e.g., healthy cells, diseased cells, immune effectors) and their interactions with the therapies [5] [4]. These are often semi-mechanistic, fit-for-purpose models that capture net effects rather than every underlying mechanism [5].

- Control Variables (

u(t)) : These represent the manipulable inputs to the system—specifically, the dosing schedules of the drugs over time [5] [10]. - Objective Functional (

J) : A mathematical expression that quantifies the therapeutic goal. It typically integrates terms representing the desired state (e.g., minimal tumor size) and the costs of intervention (e.g., drug toxicity), often with weighting factors to balance these competing objectives [5] [4]. The optimizer seeks to minimize this functional.

Pontryagin's Maximum Principle

A cornerstone of optimal control theory is Pontryagin's Maximum Principle, which provides necessary conditions for an optimal control trajectory [5]. It introduces adjoint functions (or costate variables) which quantify the sensitivity of the objective functional to changes in the system state, effectively determining how "costly" it is to deviate from the optimal path [5].

Application Notes: Protocol for Optimizing Combination Drug Regimens

This protocol outlines the process for applying optimal control to optimize a combination therapy for a specific disease, using insights from published studies on HIV, Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), and Multiple Myeloma [5] [10].

Workflow for Combination Therapy Optimization

The specific workflow for designing a combination regimen involves iterative modeling and refinement to ensure clinical feasibility.

Quantitative Results from Case Studies

The following table summarizes key outcomes from optimal control applications in different diseases, demonstrating the potential improvements over standard regimens.

Table 1: Comparative Outcomes of Standard vs. Optimal Control-Derived Regimens

| Disease Model | Therapeutic Agents | Standard Regimen Outcome | Optimal Control Outcome | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV Infection [5] | Protease Inhibitors (PIs) & Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (RTIs) | Constant dosing; CD4+ T cells dip below AIDS threshold (200 cells/µL) | High initial dose tapered over time; same total drug exposure (AUC) | Prevents progression to AIDS; ~70% higher CD4+ count at endpoint |

| Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) [5] | Targeted Therapies (u1, u2, u3) |

Best fixed-dose combination: Objective Functional = 37.9 x 10³ | Constrained optimal regimen: Objective Functional = 28.7 x 10³ | ~25% improvement in objective measure over best fixed-dose combo |

| Multiple Myeloma [10] | Pomalidomide, Dexamethasone, Elotuzumab | Not explicitly quantified | Optimal control with approximation produced a clinically-feasible, near-optimal regimen | Outperformed other optimization methods in speed and feasibility |

Successful implementation of optimal control in pharmacodynamics requires a suite of computational and experimental resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Optimal Control Studies

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Equation Solver | Software Tool | Numerically solves the system of ordinary/partial differential equations that constitute the pharmacodynamic model. Essential for simulating system dynamics. [5] |

| Optimal Control Algorithm | Software Tool | Implements optimization algorithms (e.g., based on Pontryagin's Maximum Principle or direct methods) to compute the optimal drug input u(t). [5] |

| Semi-Mechanistic Model | Mathematical Framework | A fit-for-purpose model with parameters that can be estimated from available data (individual or aggregate). Serves as the core representation of the disease and drug effects. [5] |

| Pharmacokinetic/ Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Data | Experimental Data | Used to initialize and calibrate the mathematical model. Critical for ensuring model predictions are patient-specific and clinically relevant. [4] |

| Clinical Feasibility Constraints | Protocol Parameters | Definitions of maximum tolerated doses, minimum/maximum dosing intervals, and permissible dose levels. Applied to translate theoretical optimal regimens into clinically actionable plans. [5] [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building and Calibrating a Semi-Mechanistic Model

Purpose: To create a mathematical model of disease and therapy dynamics that is suitable for optimal control.

Materials: Historical or experimental PK/PD data, differential equation solver software (e.g., MATLAB, R, Python with SciPy).

Procedure:

- Define Model Scope: Identify key state variables (e.g., for CML: quiescent leukemic cells, proliferating leukemic cells, immune effector cells) [5].

- Formulate Equations: Write differential equations describing the natural growth/death of these populations and their interactions.

- Incorporate Drug Effects: Add terms to the equations that represent the mechanism of action for each drug (e.g., increased cell death, inhibited proliferation). The effect is often modeled as a function of drug concentration [4].

- Parameter Estimation: Use numerical techniques (e.g., maximum likelihood, least-squares fitting) to estimate model parameters that best reproduce the experimental or clinical data [5] [4].

- Model Validation: Test the model's predictive power against a separate dataset not used in the calibration step.

Protocol 2: Implementing Optimal Control for Regimen Optimization

Purpose: To compute a drug dosing schedule that minimizes an objective functional representing the treatment goal.

Materials: Calibrated model from Protocol 1, optimal control software or custom code implementing Pontryagin's Maximum Principle or direct transcription methods.

Procedure:

- Formulate Objective Functional: Define

Jwhich typically integrates over time the sum of "costs" related to tumor size and drug usage. For example:J = ∫(x_tumor + w * u^2) dt, wherewis a weight penalizing high drug use [5]. - Set Constraints: Define upper and lower bounds for the control variables

u(t)(e.g., dose between 0 and MTD) and state variables [10]. - Apply Optimization Algorithm:

- For Pontryagin's approach, derive the adjoint equations and boundary conditions. Use a forward-backward sweep iterative method to find the control that minimizes the Hamiltonian [5].

- For direct methods, discretize the control problem and use nonlinear programming solvers.

- Compute and Approximate: The initial solution may suggest highly variable dosing. To ensure clinical feasibility, approximate the optimal control using a constrained number of dose levels or fixed dosing intervals [5] [10].

- In-silico Testing: Simulate the optimized regimen and compare its outcomes (via the objective functional and key biomarkers) against standard-of-care regimens in the model [5].

Challenges and Future Directions

While optimal control holds great promise, several challenges remain. Creating models that are both sufficiently detailed and calibrated with routine patient data is difficult [4]. Furthermore, translating complex, time-varying optimal schedules into practical clinical protocols requires careful consideration of adherence and hospital workflows [5]. Future opportunities lie in integrating rich, patient-specific data from quantitative imaging and genomics into these models, and in expanding the framework to optimize the combination and sequencing of modern therapies like immunotherapy with traditional modalities [4].

Modeling Heterogeneous Cell Populations with Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs)

Cell-to-cell heterogeneity is a fundamental characteristic of biological systems, evident in contexts ranging from bacterial stress responses to the diverse functional roles of mammalian immune and neuronal cells [11]. This variability, often arising from stochastic gene expression and epigenetic regulation, significantly impacts cellular responses to stimuli, including therapeutic agents [11]. While traditional bulk-scale experimental methods often mask this heterogeneity, techniques like flow cytometry, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), and time-lapse microscopy now provide the necessary resolution to observe and quantify single-cell characteristics [12] [11].

Computational models are essential for interpreting this complex snapshot data and unraveling the dynamics of cellular subpopulations. ODE constrained mixture models (ODE-MMs) represent a powerful synthesis of statistical and mechanistic modeling approaches [12]. This framework describes an overall heterogeneous cell population as a weighted sum of K distinct subpopulations, each represented by a specific probability distribution (e.g., normal, log-normal). The core mixture model is defined as shown in the equation below, where each cell measurement y is modeled as arising from one of K components, each with its own parameters θ_k and weight w_k [12].

Core ODE-MM Equation:

p(y | θ, w) = Σ (k=1 to K) w_k * p_k(y | θ_k)

The critical innovation of ODE-MMs is that the parameters θ_k of these statistical distributions are not independent; they are governed by mechanistic ordinary differential equation models derived from known or hypothesized pathway topologies [12]. This constraint allows the model to simultaneously analyze multiple experimental conditions (e.g., different time points or drug doses), infer the dynamics of unmeasured molecular species, and identify potential causal factors driving population heterogeneity, moving beyond mere observation to mechanistic insight and prediction.

ODE-MM Protocol: From Experimental Data to Validated Model

This protocol provides a detailed workflow for applying ODE-MMs to analyze heterogeneous cell populations, particularly in the context of drug response studies. The procedure is divided into five critical stages, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Experimental Design and Data Collection

- Define Biological Question and System: Clearly articulate the sources of heterogeneity under investigation (e.g., stochastic expression, differential pathway activation). Select a relevant biological system, such as primary sensory neurons or cancer cell lines [12].

- Choose Single-Cell Assays: Employ technologies that provide single-cell resolution.

- For Protein Expression/Phosphorylation: Use flow cytometry or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). These are ideal for quantifying levels and modifications of specific proteins at the single-cell level [12] [11].

- For Transcriptomic Analysis: Use single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). This provides a comprehensive view of gene expression heterogeneity across the population [11].

- For Longitudinal, Time-Resolved Data: Use time-lapse microscopy. This allows tracking of individual cells over time, capturing dynamic changes [11].

- Plan Experimental Conditions: Design experiments that include multiple time points and a range of drug concentrations or combinations to capture dynamic and dose-dependent responses. Ensure that control conditions (e.g., untreated or vehicle-treated) are included for baseline measurements [12] [13].

Data Preprocessing and Initial Analysis

- Data Extraction and Normalization: For longitudinal data (e.g., tumor volume or fluorescent signal intensity), normalize measurements for each experimental subject (e.g., animal, cell culture well) against its baseline measurement at the treatment initiation time point [13].

- Initial Population Analysis: Perform an initial, model-free analysis of snapshot data (e.g., from flow cytometry or scRNA-seq) using methods like kernel density estimation (KDE) or simple Gaussian mixture models. This helps visualize the overall population structure and informs initial guesses for the number of subpopulations

K[12].

Model Formulation and Implementation

- Formulate the Mechanistic ODE Model: Based on existing literature and biological knowledge, draft a system of ODEs describing the key signaling or regulatory pathways relevant to the measured output.

- Example: For NGF-induced Erk1/2 phosphorylation, the ODE system would describe the dynamics of NGF receptor binding, downstream kinase activation, and Erk phosphorylation [12].

- Define Subpopulation Hypotheses: Formulate testable hypotheses about the source of heterogeneity. This could be differences in:

- Initial conditions (e.g., varying basal expression levels of a receptor).

- Kinetic parameters (e.g., different rate constants for a reaction across subpopulations).

- Model structure (e.g., the presence or absence of a specific feedback loop) [12].

- Implement the ODE-MM: Couple the mixture model with the ODE system. The ODEs will determine the mean

μ_k(t)of each mixture componentkat timet, while other distribution parameters (e.g., variance) can be estimated or also modeled. This creates a unified objective function for parameter estimation.

Parameter Estimation and Model Fitting

- Select an Optimization Algorithm: Use appropriate numerical optimization techniques (e.g., maximum likelihood estimation, Bayesian inference) to fit the ODE-MM to the collected single-cell data. The goal is to find the model parameters (both ODE and mixture) that best explain the observed distributions across all experimental conditions [12].

- Utilize Computational Tools: Implement the model using scientific computing environments like R or Python. For specialized in vivo drug combination analysis with longitudinal data, tools like SynergyLMM can be adapted, as they use mixed-effects models to account for inter-animal heterogeneity and temporal dynamics [13].

Model Validation and Analysis

- Statistical Validation: Use statistical tests and diagnostic plots (e.g., residual analysis, goodness-of-fit tests like AIC/BIC) to validate the model. SynergyLMM, for instance, provides built-in functions for model diagnostics and identifying outliers [13].

- Experimental Validation: Design independent experiments to test key model predictions.

- Co-labelling Experiments: As performed in the NGF-Erk study, use additional markers to experimentally isolate and confirm the existence and properties of subpopulations predicted by the model [12].

- Perturbation Studies: Test the model's predictive power by simulating and then experimentally implementing a perturbation (e.g., a drug combination) not used in the original model training.

Table 1: Key Parameters for ODE-MM Implementation and Estimation

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Description | Estimation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture Model Parameters | Number of Components (K) |

The number of distinct subpopulations. | Model selection criteria (AIC/BIC) [12] |

Weight (w_k) |

The relative size/fraction of the k-th subpopulation. | Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) [12] | |

Distribution Parameters (θ_k) |

e.g., mean (μk) and variance (σ²k) for a normal component. | MLE, constrained by ODEs [12] | |

| ODE Model Parameters | Initial Conditions | Molecular species concentrations at time zero. | MLE/Bayesian Inference [12] |

| Kinetic Rate Constants | e.g., phosphorylation, synthesis, or degradation rates. | MLE/Bayesian Inference [12] | |

| Experimental Parameters | Subpopulation Sizes | Estimated percentage of cells in each subpopulation. | Derived from estimated weights w_k [12] |

| Synergy Score (SS) | Quantifies deviation from additive drug effect (e.g., Bliss, HSA). | Calculated from estimated ODE growth parameters [13] |

Figure 1: A workflow diagram for implementing ODE constrained mixture models (ODE-MMs), outlining the key stages from experimental design to model validation and analysis.

Case Study: NGF-Induced Erk Signaling and Drug Combination Synergy

Application to NGF-Induced Erk Phosphorylation in Sensory Neurons

The ODE-MM approach was successfully applied to investigate the highly heterogeneous process of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF)-induced Erk1/2 phosphorylation in primary sensory neurons, a pathway relevant to inflammatory and neuropathic pain [12]. A mechanistic ODE model for the Erk signaling pathway was developed based on established pathway topology. The heterogeneity in observed phosphorylation levels across the population was modeled by hypothesizing distinct subpopulations differing in their ODE model parameters, such as expression levels of key signaling components [12]. The ODE-MM analysis, using flow cytometry snapshot data, enabled the reconstruction of static and dynamic subpopulation characteristics across different experimental conditions. The model's predictions regarding the existence and properties of these subpopulations were subsequently validated through co-labelling experiments, confirming its capability to reveal novel mechanistic insights that were not apparent from the raw data alone [12].

Analysis of In Vivo Drug Combination Effects with SynergyLMM

In the context of optimizing combination drug regimens, the SynergyLMM framework provides a robust statistical method for analyzing in vivo drug combination experiments, explicitly accounting for inter-animal heterogeneity and longitudinal data [13]. The workflow involves normalizing longitudinal tumor burden data, fitting a (non-)linear mixed-effects model (exponential or Gompertz growth) to estimate treatment group-specific growth rates, and then calculating time-resolved synergy scores (SS) based on reference models like Bliss Independence or Highest Single Agent (HSA) [13]. This method is critical for determining whether a drug combination effect is truly synergistic or merely additive, and how this interaction evolves over time, providing essential information for optimal control of drug regimens.

Table 2: Experimental Design for Preclinical Drug Combination Evaluation

| Element | Description | Considerations for Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Units | Mouse models (e.g., PDX, syngeneic) | Account for inter-animal variability in tumor growth rates and treatment response [13]. |

| Treatment Groups | Control, Drug A monotherapy, Drug B monotherapy, Drug A+B Combination. | Must include all relevant monotherapies for proper synergy calculation [13]. |

| Primary Data | Longitudinal tumor volume measurements. | Normalize to baseline at treatment initiation for each animal [13]. |

| Synergy Reference Models | Bliss Independence, Highest Single Agent (HSA), Response Additivity. | Different models can yield different interpretations; selection should be biologically justified [13]. |

| Key Output | Time-resolved Synergy Score (SS) with confidence intervals and p-values. | Allows identification of when during therapy synergy/antagonism occurs [13]. |

Figure 2: A simplified ODE-based signaling pathway for NGF-induced Erk phosphorylation. The pathway is initiated by NGF binding to its receptor (TrkA), triggering a canonical kinase cascade (Ras->Raf->Mek->Erk). A key feature of such models is often a negative feedback loop (dashed line), where active, phosphorylated Erk (Erk-P) inhibits upstream signaling components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for ODE-MM Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometer / FACS | Measures protein expression/phosphorylation in single-cell suspensions. Enables sorting of subpopulations for validation. | Used for snapshot data of NGF-induced Erk phosphorylation [12]. |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | Profiles genome-wide transcriptional heterogeneity in single cells. | Identifies distinct cellular states and subpopulations; useful for informing ODE-MM structure [11]. |

| Time-Lapse Microscopy | Tracks dynamic processes in individual cells over time. | Provides longitudinal single-cell data for model calibration [11]. |

| ODE-MM Software | Computational environment for model implementation, fitting, and analysis. | R, Python (SciPy, PyMC). Specialized tools: SynergyLMM for in vivo combination studies [13]. |

| Synergy Reference Models | Statistical frameworks for defining and quantifying drug interactions. | Bliss Independence: Assumes drugs act independently. Highest Single Agent (HSA): Compares combination to best monotherapy. Selection impacts conclusions [13]. |

| Model Diagnostics Tools | Validates model fit and checks statistical assumptions. | SynergyLMM provides functions for outlier detection and influence analysis [13]. |

| Praeruptorin A | Praeruptorin A, CAS:73069-27-9, MF:C21H22O7, MW:386.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Methylformamide-d1 | N-Methylformamide-d1, MF:C2H5NO, MW:60.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Incorporating Drug Synergies and Multiplicative Control Effects

The optimization of combination drug regimens represents a frontier in therapeutic development for complex diseases, particularly in oncology and infectious disease treatment. The core challenge lies in navigating a vast search space of potential drug pairs, dosing schedules, and sequences to identify regimens that maximize synergistic therapeutic effects while minimizing antagonistic interactions and toxicity. Traditional experimental screening methods are prohibitively resource-intensive and low-throughput, unable to systematically evaluate the combinatorial possibilities [14]. This protocol details integrated computational and experimental frameworks that leverage multi-source data integration and mathematical optimization to rationally design and prioritize optimal combination drug regimens. These methodologies are framed within the broader thesis that optimal control methods provide a principled, systematic approach for overcoming the empirical limitations that have historically constrained combination therapy development.

Computational Prediction of Synergistic Drug Combinations

Multi-Source Data Integration with MultiSyn Framework

The MultiSyn framework is a deep learning approach designed to accurately predict synergistic drug combinations by integrating multi-omics data, biological networks, and detailed drug structural information [15]. Its implementation involves a semi-supervised learning architecture that processes cell line and drug data through specialized modules.

Protocol: Implementing the MultiSyn Framework

Cell Line Representation Construction

- Input Data Acquisition: Collect multi-omics data for cell lines, including gene expression profiles from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), gene mutation data from COSMIC, and protein-protein interaction (PPI) data from the STRING database [15].

- Network Integration: Construct an attributed graph for each cell line where nodes represent proteins from the PPI network. Node features are initialized using the collected multi-omics data.

- Feature Embedding: Utilize a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to process the attributed PPI graph. This step generates an initial cell line feature embedding that encapsulates the biological network context [15].

- Feature Refinement: Adaptively integrate the initial graph-based embedding with normalized gene expression profiles. This refines the cell line representation to capture both local network topology and global genomic context [15].

Drug Representation Learning

- Molecular Decomposition: Decompose each drug molecule, represented by its SMILES string (sourced from DrugBank), into chemical fragments containing pharmacophore information based on chemical reaction rules [15].

- Heterogeneous Graph Construction: Represent each drug as a heterogeneous graph comprising two node types: atom nodes and pharmacophore fragment nodes.

- Multi-View Representation: Employ a heterogeneous graph transformer to learn multi-view representations of the drug's molecular graph. This captures complex structural information and functional groups critical for biological activity [15].

Synergy Prediction

- Feature Fusion: For a given drug-cell line triplet (Drug A, Drug B, Cell Line), combine the learned features of the two drugs with the feature representation of the cell line.

- Output: Feed the fused feature vector into a final predictor (e.g., a fully connected neural network) to output a continuous synergy score [15].

Model Training and Validation

- Data: Use a benchmark dataset such as the preprocessed O'Neil drug combination dataset, which contains 12,415 drug-drug-cell line triplets [15].

- Validation: Perform 5-fold cross-validation and employ leave-one-out strategies (leaving out specific drugs, drug pairs, or tissue types) to rigorously assess the model's predictive performance and generalization ability [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core data integration and processing workflow of the MultiSyn framework:

Pairwise Building Block Approach for High-Order Combinations

For diseases like tuberculosis requiring three or more drugs, a pairwise prediction strategy offers a resource-efficient method to navigate the immense combinatorial space [16].

Protocol: Predicting High-Order Combinations from Pairwise Data

Pairwise Combination Screening:

- Select a panel of candidate drugs (e.g., 12 anti-TB antibiotics).

- Systematically measure all possible pairwise drug combinations (e.g., 66 pairs for 12 drugs) across a panel of in vitro growth conditions mimicking in vivo environments (e.g., standard, acidic, hypoxic, cholesterol-rich media) [16].

- For each dose-response curve, calculate metrics capturing combination potency (e.g., AUC₂₅, Eᵢₙf, GRᵢₙf) and drug interaction (e.g., log₂FIC₅₀, log₂FIC₉₀) [16].

Feature Vector Assembly:

- For any prospective high-order (3- or 4-drug) combination, represent it as a feature vector. This vector is composed of the summary statistics (e.g., mean, maximum) of all the in vitro metrics from the underlying pairwise combinations that constitute it [16].

Machine Learning Model Training:

- Train a classifier (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) using the feature vectors of combinations with known in vivo treatment outcomes (e.g., from a relapsing mouse model).

- The model learns to associate specific patterns of pairwise interaction metrics with successful in vivo outcomes, such as treatment shortening or superior efficacy compared to a standard regimen [16].

Ruleset Derivation and Interpretation:

- Translate the trained model into simple, interpretable rulesets for combination design. For example, an effective rule might be: "Combine one drug pair that is synergistic in a dormancy model with another pair that is highly potent in a cholesterol-rich environment" [16]. This transforms a black-box prediction into a rational design principle.

Mathematical Optimization of Combination Regimens

Optimal Control Theory for Regimen Design

Optimal Control Theory (OCT) provides a mathematical formalism for determining the dosing schedules that optimize a defined therapeutic objective over time, moving beyond fixed-dose combinations to dynamic regimens [5] [4].

Protocol: Formulating an Optimal Control Problem for Combination Therapy

Develop a Semi-Mechanistic Disease-Treatment Model:

- Construct a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that captures key biological compartments and their interactions. For example, a model for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) might include compartments for quiescent leukemic stem cells, proliferating leukemic cells, and immune effector cells [5] [10].

- Incorporate the pharmacodynamic effects of each drug as modulatory terms (e.g., increased cell death, inhibited proliferation) within the ODE system. The drug doses, u(t), are the time-dependent control functions to be optimized [5].

Define the Objective Functional:

- Formulate a mathematical expression that quantifies the treatment goal. This typically aims to maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing toxicity and drug usage.

- A canonical form is: J(u) = ∫[Tumor Burden] + β * ∫[Toxicity] + γ * ∫[Drug Dose] dt. The weights β and γ balance the competing objectives [5] [10] [4].

Apply Pontryagin's Maximum Principle:

- This technique transforms the optimization problem into a two-point boundary value problem by introducing adjoint functions for each model state variable [5].

- The solution yields the optimal control trajectory, u(t), which specifies how drug doses should vary over the entire treatment horizon to maximize the objective functional [5].

Implement Clinically Feasible Approximations:

- The highly variable dosing profiles predicted by the pure optimal control solution are often impractical for clinical administration.

- Impose constraints to derive a feasible regimen, such as fixed dose levels with less frequent timing changes (e.g., daily or weekly dosing), that approximates the optimal solution while remaining clinically actionable [5]. This constrained approximation has been shown to predict regimens that are about 25% better than the best fixed-dose combination in a CML model [5].

The workflow for applying optimal control to regimen optimization is outlined below:

Quantitative Assessment of Drug Synergism

Before optimization, the synergistic interaction between drugs must be quantitatively confirmed using rigorous statistical methods applied to dose-effect data [17].

Protocol: Isobolographic Analysis for Synergy Validation

Dose-Response Curve Generation:

- For each drug individually, and for a fixed-ratio combination of the two drugs, conduct experiments to measure the effect (e.g., % cell kill, tumor size reduction) across a range of doses.

- Fit appropriate dose-response models (e.g., sigmoid Eₘâ‚x model) to the data for Drug A, Drug B, and the combination [17].

Construct the Additive Isobole:

- Select an effect level (e.g., EDâ‚…â‚€, the dose producing 50% of maximum effect).

- Plot the EDâ‚…â‚€ of Drug A on the x-axis and the EDâ‚…â‚€ of Drug B on the y-axis. The straight line connecting these two points is the additive isobole. It represents all dose pairs (a, b) expected to produce the EDâ‚…â‚€ effect if the drugs interact additatively [17].

- The equation for the additive isobole is: a/A + b/B = 1, where A and B are the individual EDâ‚…â‚€ doses [17].

Experimental Testing and Statistical Comparison:

- Experimentally determine the actual dose combination (a, b) that produces the EDâ‚…â‚€ effect.

- Plot this experimental point on the isobologram.

- Synergy is declared if the experimental point lies significantly below the additive isobole, indicating the effect was achieved with lower doses than expected. Antagonism is indicated if the point lies significantly above the line [17].

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Combination Therapy Studies

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Provides genomic and gene expression data for a wide array of cancer cell lines, used for featurizing cellular models. | Broad Institute [15] |

| STRING Database | A database of known and predicted Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs), used to construct biological networks for context-aware modeling. | EMBL [15] |

| DrugBank | A comprehensive database containing drug chemical structures, SMILES strings, and target information. | [15] |

| O'Neil Drug Combination Dataset | A benchmark dataset containing experimentally measured synergy scores for drug combinations on cancer cell lines. | [15] |

| Relapsing Mouse Model (RMM) | A preclinical in vivo model used for evaluating the treatment efficacy of drug combinations, particularly for infectious diseases like TB. | [16] |

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Drug Combination Analysis

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Bliss Independence Score | S = E_{A+B} - (E_A + E_B - E_A * E_B), where E is the fractional effect. | S > 0: Synergy;S = 0: Additive;S < 0: Antagonism [14] |

| Combination Index (CI) | CI = (C_{A,x}/IC_{x,A}) + (C_{B,x}/IC_{x,B}) | CI < 1: Synergy;CI = 1: Additive;CI > 1: Antagonism [14] |

| Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) | FIC = (MIC of Drug A in combo / MIC of Drug A alone) + (MIC of Drug B in combo / MIC of Drug B alone) | Similar interpretation to CI. logâ‚‚FIC is often used [16]. |

| Isobologram Analysis | Graphical analysis based on dose equivalence: a/A + b/B = 1 for additivity. | Point below line: Synergy;Point on line: Additive;Point above line: Antagonism [17] |

Intra-patient heterogeneity, the coexistence of diverse cellular subpopulations within a single patient's disease, represents a fundamental challenge in oncology and other therapeutic areas. This heterogeneity, combined with the nonlinear dynamics of disease progression and drug response, complicates the development of effective combination therapies. In diseases like cancer, sub-populations of cells can exhibit differential sensitivities to drugs, leading to adaptation and treatment failure [18] [19]. Optimal control theory provides a powerful mathematical framework to address these challenges by modeling complex cell-drug interactions and designing dosing regimens that can optimally steer heterogeneous biological systems toward therapeutic outcomes [18] [20]. This Application Note details the core challenges, quantitative models, and experimental protocols essential for advancing research in this field, with a specific focus on optimizing combination drug regimens.

Quantitative Framework and Data Presentation

Core Mathematical Components of the Optimal Control Framework

The general optimal control framework for multi-drug, multi-cell population interactions is built upon a system of coupled, semi-linear ordinary differential equations [18] [20]. The table below summarizes the key variables and matrices involved in the core model.

Table 1: Core components of the ODE model for heterogeneous cell populations under combination therapy.

| Symbol | Dimension | Description | Role in Optimal Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| x | â„â¿ | State vector representing the count of each cell type (e.g., sensitive vs. resistant subpopulations). | The system state to be controlled; the primary output of the ODE system. |

| u | â„áµ | Control vector representing the effective pharmacodynamic action of each drug (normalized from 0 to 1). | The input to be optimized by the control framework to minimize the cost functional. |

| A | â„â¿Ë£â¿ | State matrix governing intrinsic cell dynamics (e.g., proliferation, spontaneous conversion). | Defines the baseline, untreated growth and conversion dynamics of the heterogeneous population. |

| B | â„â¿Ë£áµ | Control matrix for terms linear in u but independent of x. | Captures direct drug effects that are not dependent on the current population size. |

| L(u, x) | â„â¿ | Terms for drug effects linear in u (e.g., monomials of the form uâ‚–xáµ¢). | Models proportional drug-induced killing or conversion. |

| N(u, x) | â„â¿ | Terms for nonlinear drug-drug interactions (e.g., polynomials of the form xáµ¢uâ‚–uâ„“). | Explicitly captures synergistic or antagonistic interactions between drugs. |

| J(u) | Scalar | Cost functional balancing treatment efficacy (final tumor burden) with penalties for toxicity and cost. | The objective function to be minimized; its structure dictates the optimal dosing strategy. |

Modeling Heterogeneity: A Distribution-Based Approach

Moving beyond simple sensitive/resistant binary models, a more powerful approach treats drug sensitivity as a continuous spectrum across the cell population. This mechanistic, "population-tumor kinetic" (pop-TK) model can be described by the following integral, which calculates the total number of cells surviving a treatment cycle [19]: [ \text{Cells after treatment} = \int N(x) F(x, D) dx ] Here, ( N(x) ) represents the initial distribution of cells across different drug sensitivity levels ( x ), and ( F(x, D) ) is the dose-response function describing the fraction of cells with sensitivity ( x ) that survive a drug dose ( D ). This formulation allows the simulation of how repeated therapy cycles progressively shift the tumor population toward resistance, a classic clinical scenario [19].

Table 2: Key techniques for quantifying and modeling intra-patient and inter-patient heterogeneity.

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Strength | Notable Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Mixed Effects (NLME) Modeling | Inferring population-level parameter distributions from sparse patient data. | Efficiently quantifies inter-patient variability (IPV) and its impact on PK/PD. | Model misspecification can lead to biased parameter estimates. |

| Virtual Populations (Virtual Pop) | Generating in-silico patients for simulating clinical trials and testing dosing regimens. | Allows for exploration of variability and optimization without risking patients. | Requires robust assumptions about underlying parameter distributions. |

| Bayesian Techniques | Updating prior knowledge of parameter distributions with new patient data. | Provides a formal probabilistic framework for personalized forecasting. | Computationally intensive and requires careful selection of priors. |

| Non-parametric Estimation | Estimating distributions without assuming a specific functional form (e.g., log-normal). | Highly flexible and data-driven. | Requires large sample sizes for accurate estimation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Establishing a Calibrated Virtual Population for In-Silico Trials

Objective: To create a computationally generated cohort of virtual patients that accurately reflects the observed inter-patient and intra-tumor heterogeneity in drug sensitivity, for the purpose of simulating combination therapy outcomes and optimizing dosing regimens in silico.

Materials:

- Patient-derived genomic, transcriptomic, or drug sensitivity data.

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or cloud computing resources.

- Statistical software (e.g., R, Python with SciPy/NumPy libraries).

Procedure:

- Data Collection & Preprocessing: Collate raw data on drug sensitivity from in-vitro screens (e.g., dose-response curves) or clinical biomarkers from a representative patient cohort.

- Parameter Estimation: Use nonlinear mixed-effects (NLME) modeling or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to fit a log-normal (or other appropriate) distribution to the drug sensitivity data for each agent and potential cell subtype [19] [21].

- Virtual Population Generation: Randomly sample a large number (e.g., N=10,000) of parameter sets from the fitted distributions. Each unique parameter set defines one virtual patient with a specific initial distribution of drug-sensitive and -resistant cells.

- Model Validation: Simulate a standard-of-care regimen across the virtual population. Compare the simulated distribution of outcomes (e.g., progression-free survival) to real-world historical data from a separate cohort to validate the model's predictive power [19].

- In-Silico Trial Execution: Implement the optimal control-predicted dosing regimens or novel combination strategies in the validated virtual population. Evaluate primary endpoints (e.g., cure rate, time to progression) and secondary endpoints (e.g., toxicity burden).

Protocol: Functional Validation of Synergistic Drug Interactions

Objective: To empirically quantify drug-drug synergies in heterogeneous cell models and parameterize the nonlinear interaction term ( N(\mathbf{u}, \mathbf{x}) ) in the optimal control model.

Materials:

- Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) or a co-culture of isogenic cell lines with known differential drug sensitivities.

- Drugs for combination therapy.

- High-throughput cell imaging and viability assay system (e.g., Incucyte).

- Flow cytometer for tracking cell population composition.

Procedure:

- Experimental Setup: Establish a 3D in-vitro model (e.g., PDOs) that retains the cellular heterogeneity of the original tumor. Alternatively, create a co-culture system with fluorescently tagged sensitive and resistant cell lines.

- Dose-Response Matrix Treatment: Treat models with a full matrix of drug concentrations (e.g., 8x8 serial dilutions) for each drug alone and in combination. Include multiple replicates and vehicle controls.

- High-Throughput Time-Lapse Imaging: Monitor cell viability and population composition (via fluorescent tags or specific markers) every 12-24 hours over a 5-7 day period using live-cell imaging.

- Data Extraction and Synergy Calculation: Extract time-kill curves and dose-response matrices at multiple time points. Calculate synergy scores using reference models like Loewe additivity or Bliss independence to quantify the magnitude and direction of drug interactions [18].

- Model Parameterization: Fit the experimental data (cell counts over time under various combination doses) to the ODE model structure (Equation 1). The estimated coefficients for the polynomial terms ( \mathbf{x}i\mathbf{u}k\mathbf{u}_\ell ) will define the ( N(\mathbf{u}, \mathbf{x}) ) matrix, concretely capturing the synergistic or antagonistic interaction for use in optimal control simulations.

Visualizing Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: Optimal Control Workflow for Heterogeneous Populations

Diagram: Modeling Drug Sensitivity as a Distribution

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for studying heterogeneity and optimizing control.

| Category / Item | Specific Example / Platform | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| In-Vitro Heterogeneity Models | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs); Isogenic Co-culture Systems | Preserves the cellular heterogeneity and tumor microenvironment of the original patient sample for ex-vivo drug testing. |

| High-Throughput Screening | Incucyte Live-Cell Analysis System; Multiplexed Viability Assays | Enables longitudinal, high-content monitoring of cell population dynamics in response to a matrix of drug combinations. |

| Synergy Calculation Software | R Synergy Package; Combenefit |

Quantifies drug-drug interactions from dose-response matrix data using standardized reference models (Loewe, Bliss). |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | MATLAB with Optim. Toolbox; Python (SciPy, NumPy, CVXPY) | Solves systems of ODEs and performs numerical optimization to compute optimal control trajectories. |

| Virtual Population Generators | Pop-TK Modeling Framework [19]; Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Software (NONMEM, Monolix) | Generates in-silico patient cohorts with realistic inter-patient variability for simulating clinical trials. |

| Biomarker Detection Kits | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing; Digital PCR for MRD Detection | Identifies and tracks minority resistant subclones before, during, and after treatment to inform model structure and parameters. |

| 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-PC-d31 | 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-PC-d31, CAS:179093-76-6, MF:C42H82NO8P, MW:791.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nifedipine d4 | Nifedipine d4, CAS:1219798-99-8, MF:C17H18N2O6, MW:350.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodologies in Action: From Theoretical Frameworks to Case Studies

A General ODE Framework for Multi-Drug, Multi-Population Control

Combination drug therapies are a cornerstone of modern treatment for complex diseases, particularly in oncology, where they exploit drug synergies and address diverse cell populations within target tissues [18]. However, designing these treatments is challenging due to the difficulty in predicting responses of different cell types to individual drugs and their combinations [18]. A General ODE Framework for Multi-Drug, Multi-Population Control addresses this by providing a unified mathematical structure to model treatment response, integrating cell heterogeneity, multi-drug synergies, and practical constraints like toxicity [18]. This framework is a pivotal component of a broader thesis on optimal control methods for optimizing combination drug regimens, offering a systematic approach to personalizing therapy and improving patient outcomes.

Core Framework and Mathematical Formulation

The framework models the dynamics of a heterogeneous cell population under the influence of multiple interacting drugs. The system is governed by a set of coupled, semi-linear ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that capture cell proliferation, death, differentiation, and drug-mediated effects [18].

System State and Control Variables

The system's state is described by a vector (\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n), where each component (xi) represents the population size of the (i)-th cell type. The pharmacodynamic effects of (m) different drugs are represented by a control vector (\mathbf{u} \in \mathbb{R}^m), where each (uk) is constrained between 0 (no effect) and 1 (maximum effect) [18].

Governing Ordinary Differential Equations

The general ODE for the (j)-th cell population is formulated as:

[ \frac{dxj}{dt} = \text{Growth}j(\mathbf{x}) - \text{Death}j(\mathbf{x}) + \sum{i} \left[ \text{Conversion}{i \to j}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{u}) \right] + \sum{k} \left[ \text{DrugEffect}{j,k}(\mathbf{x}, uk) \right] + \sum{k, \ell} \left[ \text{Synergy}{j,k,\ell}(\mathbf{x}, uk, u\ell) \right] ]

Table 1: Components of the Multi-Population, Multi-Drug ODE Model

| Component | Mathematical Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Growth | ( \lambdaj xj ) | Net proliferation rate of cell type (j) in the absence of drugs. |

| Drug-Mediated Death | ( -\sumk \delta{j,k} uk xj ) | Death of cell type (j) induced by drug (k). |

| Spontaneous Conversion | ( \sum{i \neq j} (\rho{i \to j} xi - \rho{j \to i} x_j) ) | Phenotypic switching from cell type (i) to (j) at rate (\rho). |

| Drug-Induced Conversion | ( \sum{i \neq j} \sumk \omega{i \to j, k} uk x_i ) | Drug (k)-mediated differentiation of cell type (i) into type (j). |

| Drug-Drug Synergy | ( \sum{k < \ell} \sigma{j,k,\ell} uk u\ell x_j ) | Enhanced effect on cell type (j) from the interaction of drugs (k) and (\ell). |

This formulation uses a minimal model of drug interactions, excluding higher-order terms like (u_k^2) which do not represent true synergy [18]. The framework focuses on pharmacodynamics, deliberately abstracting away complex, drug-specific pharmacokinetics to maintain generality [18].

Figure 1: Logical structure of the general ODE framework, showing core components and their relationships.

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the ODE Framework for a Specific Cancer Type

This protocol outlines the steps to adapt the general ODE framework to model a specific cancer type, such as ovarian cancer, treated with a synergistic drug combination [18].

Objective: To calibrate and simulate a two-population cancer model for predicting optimal combination therapy dosing.

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ODE Framework Implementation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ODE Numerical Solver | Solves the system of differential equations. | Use MATLAB ode45 or Python scipy.integrate.solve_ivp. |

| Parameter Estimation Algorithm | Fits model parameters to experimental data. | Non-linear least squares (e.g., scipy.optimize.curve_fit). |

| Optimal Control Solver | Computes the optimal drug dosing schedule. | Pontryagin's Maximum Principle or direct methods. |

| Experimental Viability Data | Used for model calibration and validation. | Time-kill assay data for single drugs and combinations. |

| Synergy Index Calculator | Quantifies drug-drug interactions. | Bliss Independence or Loewe Additivity models. |

Procedure:

- Define Cell Populations: Identify the relevant heterogeneous cell subpopulations (e.g., drug-sensitive and drug-tolerant persister cells in ovarian cancer [18]).

- Specify Drug Actions: Define the control vector (\mathbf{u}). For a two-drug regimen (e.g., Drug A and Drug B), (\mathbf{u} = (uA, uB)).

- Parameterize the Model:

- Estimate baseline growth rates ((\lambdaj)) from untreated control data.

- Fit drug-induced death rates ((\delta{j,k})) from single-agent time-kill assays.

- Quantify synergy parameters ((\sigma_{j,k,\ell})) from combination dose-response matrices using a Bliss independence model [22].

- Model Validation: Simulate the calibrated ODE model under a validation dosing regimen not used for parameter fitting. Compare the model output (e.g., total tumor cell count over time) against experimental results.

Protocol 2: Optimal Control Solution for Adaptive Therapy

This protocol describes how to derive an optimal control solution ( \mathbf{u}^*(t) ) from the parameterized ODE model to achieve a therapeutic objective, such as tumor minimization with constrained drug-related toxicity.

Objective: To compute a drug dosing schedule that minimizes the tumor burden over a treatment horizon ( [0, T] ) while limiting cumulative toxicity.

Materials: The calibrated ODE model from Protocol 1, an optimal control solver.

Procedure:

- Formulate the Optimal Control Problem:

- State System: The parameterized ODE model, ( \frac{d\mathbf{x}}{dt} = f(\mathbf{x}(t), \mathbf{u}(t)) ).

- Cost Functional: Define the objective to be minimized. A typical form is: [ J(\mathbf{u}) = \int_0^T \left[ Q(\mathbf{x}(t)) + \mathbf{u}(t)^T R \mathbf{u}(t) \right] dt ] Here, ( Q(\mathbf{x}(t)) ) penalizes a large tumor burden, and the quadratic term ( \mathbf{u}(t)^T R \mathbf{u}(t) ) penalizes high drug usage (a proxy for toxicity) [18] [23].

- Apply Necessary Optimality Conditions: Use Pontryagin's Maximum Principle to derive the necessary conditions for the optimal control ( \mathbf{u}^(t) ) and the corresponding state trajectory ( \mathbf{x}^(t) ). This transforms the problem into a two-point boundary value problem.

- Numerical Solution: Solve the boundary value problem numerically using a forward-backward sweep iterative method [18].

- Implement Adaptive Dosing: The solution ( \mathbf{u}^*(t) ) provides a continuous dosing schedule. For clinical translation, this can be discretized into an adaptive schedule where doses are administered at specific time points (e.g., triggered by the opening of a vessel normalization window, as monitored by a digital biomarker) [24].

Figure 2: Workflow for solving the optimal control problem derived from the ODE framework.

Case Study: Application to Brain Tumor Combination Therapy

The general framework has been successfully applied to develop a multi-input controller for brain tumors, combining radiotherapy and chemotherapy [23].

Model Extension: The core ODE model was expanded to a five-state system incorporating tumor cells ((T)), healthy cells ((N)), immune cells ((I)), radiation concentration ((R)), and chemotherapy drug concentration ((C)) [23].

Control Strategy: A novel synergetic nonlinear controller was designed to regulate the two control inputs: radiation dosage ((\alpha)) and chemotherapeutic drug dosage ((q)).

Results: The controller achieved a significant 57% reduction in baseline radiation dosage and a 33% reduction in chemotherapeutic drug dosage while effectively suppressing tumor growth [23]. This demonstrates the framework's utility in designing less toxic, yet effective, multi-treatment regimens.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential computational and analytical tools required to implement the proposed framework.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Implementing the ODE Control Framework

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Role in the Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Equation Solvers | MATLAB ODE suites, Python scipy.integrate, R deSolve |

Numerical simulation of the multi-population ODE system. |

| Parameter Estimation Software | Monolix, NONMEM, lmfit for Python |

Calibration of model parameters (e.g., ( \delta, \sigma, \rho )) from experimental data. |

| Optimal Control Algorithms | ACADO, GPOPS-II, Gekko (Python) | Numerical computation of the optimal drug dosing schedule ( \mathbf{u}^*(t) ). |

| Surrogate Modeling | Algorithm from Fonseca et al. [25] | Derives a lower-dimensional ODE surrogate from a complex Agent-Based Model for control. |

| Synergy Quantification | Bliss Independence, Loewe Additivity | Empirically determines the nature and strength of drug-drug interactions (( \sigma )) [22]. |

| 4-Methylanisole-d4 | 4-Methylanisole-d4, MF:C8H10O, MW:126.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyl-D3 methanesulfonate | Methyl-D3 methanesulfonate, CAS:91419-94-2, MF:C2H6O3S, MW:113.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The "General ODE Framework for Multi-Drug, Multi-Population Control" provides a powerful, adaptable template for modeling and optimizing combination therapies. By integrating core principles of cell population dynamics, multi-drug pharmacodynamics, and optimal control theory, it enables the rational design of dosing regimens that can effectively manage heterogeneous diseases while minimizing toxicity. The application notes and protocols detailed herein offer researchers a clear roadmap for implementing this framework, from initial model specification and calibration to the derivation of clinically-informative optimal control solutions. This structured approach is a critical step toward personalized, adaptive cancer therapies and improved patient outcomes.

Applying Pontryagin's Maximum Principle for Optimal Dosing

Optimal control theory, and Pontryagin's Maximum Principle (PMP) in particular, provides a powerful mathematical framework for determining the best possible control strategy for a dynamical system. In pharmaceutical research, this translates to computing optimal dosing regimens that can maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects and the risk of resistance development [5]. This approach is especially valuable for optimizing combination therapies and regimens for diseases like cancer, HIV, and infectious diseases where treatment dynamics are complex [5] [26] [27]. Unlike traditional "guess and check" methods, optimal control systematically identifies strategies that would be difficult to discover empirically, making it a critical tool for modern drug development pipelines.

Theoretical Foundation of Pontryagin's Principle

Pontryagin's Maximum Principle, formulated in 1956 by Lev Pontryagin and his students, was initially applied to maximize the terminal speed of a rocket [28]. The principle is now widely used to find the best possible control for taking a dynamical system from one state to another, especially in the presence of constraints.

For a dynamical system with state variable x ∈ R⿠and control u ∈ U, where U is the set of admissible controls, the system dynamics are described by ẋ = f(x, u) with initial condition x(0) = x₀ [28]. The objective is to find a control trajectory u: [0, T] → U that minimizes a cost functional:

where L(x, u) represents the running cost and Ψ(x) is the terminal cost [28].

To apply PMP, we formulate the control Hamiltonian:

where λ(t) is the adjoint variable [28]. Pontryagin's Maximum Principle states that for the optimal state trajectory x* and optimal control u*, there exists an adjoint function λ* such that:

- Minimization Condition:

H(x*(t), u*(t), λ*(t), t) ≤ H(x(t), u, λ(t), t)for allt ∈ [0, T]and allu ∈ U - Adjoint Equation:

-λ̇ᵀ(t) = Hₓ(x*(t), u*(t), λ(t), t) - Boundary Conditions:

λᵀ(T) = Ψₓ(x(T))if the final state is free [28]

These conditions transform the infinite-dimensional control problem into a two-point boundary value problem that can be solved computationally.

Application Notes for Therapeutic Optimization

Workflow for Optimal Dosing Regimen Design

The general process for applying optimal control to therapeutic dosing optimization follows a systematic workflow that integrates mathematical modeling with computational methods [5].

Key Mathematical Components for Pharmaceutical Applications

Table 1: Essential components of optimal control problems in dosing optimization

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Therapeutic Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Variables | x(t) = [xâ‚(t), xâ‚‚(t), ..., xâ‚™(t)]áµ€ |

Biological quantities (e.g., tumor size, pathogen load, drug concentration) | |

| Control Variables | u(t) = [uâ‚(t), uâ‚‚(t), ..., uₘ(t)]áµ€ |

Administered drug doses (oral, IV bolus, infusion) | |

| Dynamics | ẋ(t) = f(t, u, x) |

Disease progression and drug effect mechanisms | |

| Cost Functional | J = Ψ(x(T)) + ∫₀ᵀ L(x(t), u(t)) dt |

Treatment goal balancing efficacy and toxicity | |

| Admissible Controls | `U_ad = {u ∈ U | 0 ≤ u ≤ u_max}` | Clinically feasible dosing ranges |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimal Control for Combination Therapy in Leukemia

This protocol outlines the procedure for optimizing combination therapy in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) based on established methodologies [5].

Model Specification

Disease Dynamics: Develop a semi-mechanistic model of CML with three key populations:

- Quiescent leukemic cells (Q)

- Proliferating leukemic cells (P)

- Immune effector cells (E)

The system dynamics can be represented as:

where control u = [uâ‚, uâ‚‚, u₃] represents doses of different targeted therapies [5].

Objective Functional Formulation

Define the objective functional to minimize tumor burden while limiting drug exposure:

where weights A-G balance tumor reduction against treatment toxicity [5].

Implementation Steps

- Parameter Estimation: Estimate model parameters from preclinical or clinical data

- Hamiltonian Construction: Form

H = L(x,u) + λâ‚·fâ‚ + λ₂·fâ‚‚ + λ₃·f₃ - Adjoint System Definition: Derive adjoint equations via

-λ̇ᵀ = Hₓ - Numerical Solution: Implement forward-backward sweep algorithm

- Clinical Translation: Convert continuous optimal control to clinically feasible discrete dosing

Table 2: Performance comparison of optimized versus standard regimens in CML [5]

| Regimen (doses in mg) | Value after 5 Years (Objective Functional) | Improvement over Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Monotherapy (400, 0, 0) | 280 × 10³ | Baseline |

| Best Fixed-Dose Combination (200, 70, 80) | 37.9 × 10³ | ~86% improvement |

| Constrained Approximation to Optimal | 28.7 × 10³ | ~90% improvement |

Protocol 2: Optimal Dosing Under Drug-Induced Plasticity in Cancer

This protocol addresses the critical challenge of drug-induced plasticity, where anti-cancer drugs can accelerate the evolution of drug resistance through non-genetic mechanisms [27].

Phenotypic Switching Model

Develop a two-phenotype model capturing drug-sensitive (type-0) and drug-tolerant (type-1) cells:

where transition rates μ(c) and ν(c) depend on drug concentration c [27].

Optimal Control Formulation

Define the control problem to minimize total tumor size at final time:

Solution Strategy

- Characterize Induction Mechanisms: Determine whether the drug affects transitions to tolerance (Case I), from tolerance to sensitivity (Case II), or both (Case III) [27]

- Compute Optimal Strategy: Apply PMP to derive optimal dosing profile

- Implement Equilibrium Strategy: For linear induction (Case I), maintain constant low dose

c*that balances cell kill and tolerance induction

Protocol 3: Individualized Dosing with OptiDose Algorithm

The OptiDose algorithm provides a framework for computing individualized optimal dosing regimens for PKPD models [29].

Finite-Dimensional Control Formulation

For drugs administered at discrete times t_{i,l}, define the finite-dimensional control problem:

where u = [uâ‚, uâ‚‚, ..., u_m] are the doses administered at scheduled times [29].

Gradient Computation via Adjoint Sensitivity

- Solve State Equations: Integrate system dynamics forward in time

- Solve Adjoint Equations: Compute adjoint variables backward in time

- Calculate Gradient:

∇J(u) = ∂H/∂uevaluated along optimal trajectory - Update Controls: Apply quasi-Newton methods to iteratively improve dosing regimen

Clinical Implementation

- Patient-Specific Parameterization: Estimate individual PKPD parameters

θ_ind - Therapeutic Goal Specification: Define target profile

y_ref(t)based on clinical objectives - Regimen Optimization: Compute optimal doses

u*for scheduled administration times - Adaptive Reoptimization: Update regimen as new patient data becomes available

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential components for implementing optimal control in dosing optimization

| Tool/Reagent | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Equation Solver | MATLAB ode45, SUNDIALS CVODE, or Python solve_ivp | Numerical integration of system dynamics and adjoint equations |

| Optimization Algorithm | BFGS, Gradient Descent, or Forward-Backward Sweep | Solving optimal control problem and updating control variables |

| Parameter Estimation Framework | Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian Methods, or Monte Carlo Sampling | Estimating model parameters from experimental data |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Sobol' indices, Latin Hypercube Sampling, or Morris Method | Identifying parameters driving system behavior and treatment outcomes |

| Clinical Data | PK/PD measurements, tumor size tracking, or pathogen load | Validating model predictions and refining optimal control strategies |

| Tetradecanedioic acid-d24 | Tetradecanedioic acid-d24, MF:C14H26O4, MW:282.50 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Desmethylclozapine-d8 | N-Desmethylclozapine-d8, MF:C17H17ClN4, MW:320.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Computational Implementation Considerations