Modern Virtual Screening Protocols in Drug Discovery: AI-Driven Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary virtual screening protocols that are revolutionizing early drug discovery.

Modern Virtual Screening Protocols in Drug Discovery: AI-Driven Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary virtual screening protocols that are revolutionizing early drug discovery. Covering both foundational concepts and cutting-edge advancements, we explore the critical transition from traditional docking and pharmacophore methods to AI-accelerated platforms capable of screening billion-compound libraries. The content addresses key methodological approaches including structure-based docking, ligand-based screening, and emerging deep learning techniques, while offering practical solutions to common challenges in scoring accuracy, library management, and experimental validation. Through comparative analysis of successful case studies across diverse therapeutic targets and discussion of validation frameworks, this resource equips researchers with strategic insights for implementing robust virtual screening workflows that enhance hit identification efficiency and success rates in drug development pipelines.

Virtual Screening Fundamentals: Core Principles and Evolving Challenges in Drug Discovery

Virtual screening (VS) represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, defined as the computational technique used to search libraries of small molecules to identify those structures most likely to bind to a drug target, typically a protein receptor or enzyme [1]. This methodology serves as a critical filter that efficiently narrows billions of conceivable compounds to a manageable number of high-probability candidates for synthesis and experimental testing [1] [2]. The evolution of VS from its traditional structure-based and ligand-based origins to increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approaches has fundamentally transformed early drug discovery, offering unprecedented capabilities to explore expansive chemical spaces while significantly reducing time and costs associated with pharmaceutical development [3] [4].

The imperative for efficient virtual screening protocols stems from the substantial bottlenecks inherent in traditional drug discovery. The process of bringing a new drug to market typically requires 12 years and exceeds $2.6 billion in costs, with approximately 90% of candidates failing during clinical trials [5]. Virtual screening addresses these challenges by enabling researchers to computationally evaluate vast molecular libraries before committing to resource-intensive laboratory experiments and clinical trials [2]. This application note details established and emerging virtual screening methodologies, providing structured protocols and analytical frameworks to guide research planning and implementation within comprehensive drug discovery workflows.

Fundamental Approaches to Virtual Screening

Virtual screening methodologies are broadly categorized into two distinct but complementary paradigms: structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) and ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS). The selection between these approaches depends primarily on available structural and bioactivity information about the molecular target and its known binders.

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS)

SBVS relies on the three-dimensional structural information of the biological target, typically obtained through X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [1] [2]. This approach encompasses computational techniques that directly model the interaction between candidate ligands and the target structure, with molecular docking representing the most widely employed method [2].

Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation and binding conformation of a small molecule (ligand) within a specific binding site of a target macromolecule (receptor) to form a stable complex [2]. The docking process involves two fundamental components: a search algorithm that explores possible ligand conformations and orientations within the binding site, and a scoring function that estimates the binding affinity of each predicted pose [1]. Popular docking software includes DOCK, AutoDock Vina, and similar packages that have evolved to incorporate genetic algorithms and molecular dynamics simulations [6].

The primary advantage of SBVS lies in its ability to identify novel scaffold compounds without requiring known active ligands, making it particularly valuable for pioneering targets with limited chemical precedent [1]. Limitations include computational intensity, sensitivity to protein flexibility, and potential inaccuracies in scoring function predictions [2].

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS)

When three-dimensional structural data for the target is unavailable, LBVS offers a powerful alternative by leveraging known active compounds to identify new candidates [1]. This approach operates on the fundamental principle that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [1] [2].

LBVS methodologies include:

- Pharmacophore Modeling: Identifies essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition at a receptor binding site [1].

- Shape-Based Similarity Screening: Compares three-dimensional molecular shapes to identify compounds with similar steric properties to known actives, with ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) representing the industry standard [1].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling: Develops predictive models that correlate quantitative molecular descriptors with biological activity levels [1] [2].

- Molecular Similarity Analysis: Employs chemical descriptor systems and similarity metrics (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient) to identify structurally analogous compounds [1] [2].

LBVS typically requires less computational resources than SBVS but depends critically on the quality, diversity, and relevance of known active compounds used as reference structures [1].

Hybrid Screening Approaches

Emerging hybrid methodologies integrate both structural and ligand-based information to overcome limitations of individual approaches [1]. These methods leverage evolutionary-based ligand-binding information to predict small-molecule binders by combining global structural similarity and pocket similarity assessments [1]. For instance, the PoLi approach employs pocket-centric screening that targets specific binding pockets in holo-protein templates, addressing stereochemical recognition challenges that limit traditional 2D similarity methods [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Virtual Screening Approaches

| Feature | Structure-Based (SBVS) | Ligand-Based (LBVS) | Hybrid Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required Input | 3D protein structure | Known active compounds | Both protein structure and known actives |

| Primary Methodology | Molecular docking | Chemical similarity search | Combined similarity and pocket matching |

| Computational Demand | High | Low to moderate | Moderate to high |

| Advantages | No known ligands needed; novel scaffold identification | Fast; high-throughput capability | Improved accuracy; leverages complementary data |

| Limitations | Protein flexibility challenges; scoring function accuracy | Limited by known chemical space | Implementation complexity; data integration challenges |

AI-Driven Transformations in Virtual Screening

Artificial intelligence has revolutionized virtual screening by introducing data-driven predictive modeling that transcends the limitations of traditional rule-based simulations [4] [7]. AI-enhanced virtual screening leverages machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) to improve fidelity, efficiency, and scalability across both structure-based and ligand-based paradigms [7].

Machine Learning Applications

Machine learning algorithms serve as the foundation for AI-enhanced virtual screening strategies, with several distinct implementations:

Predictive QSAR Modeling: ML algorithms including Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Decision Trees develop quantitative structure-activity relationship models that correlate physicochemical properties and molecular descriptors with biological activities [7]. These models rank compounds by predicted bioactivity, reducing false positives and guiding lead selection [7].

Classification and Regression Tasks: Advanced ML methods classify candidate molecules as active/inactive and estimate binding scores as regression problems, enabling efficient prioritization of diverse compound libraries [7].

Docking Integration and Rescoring: ML algorithms complement traditional docking by rescoring poses or predicting interaction energy more accurately than standard scoring functions, improving enrichment factors by up to 20% in top-ranked compounds [7].

ADMET Property Prediction: ML models predict critical absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties, integrating these essential pharmacokinetic considerations early in the screening workflow [7].

Deep Learning Frameworks

Deep learning architectures have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in processing high-dimensional chemical data:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Naturally model molecular structures as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) to learn representations capturing both local and global molecular features, outperforming traditional descriptor-based models in binding affinity and ADMET profile prediction [7].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Analyze three-dimensional structures of protein-ligand complexes, learning spatial hierarchies from molecular configurations to predict interaction potentials and binding conformations with high accuracy [7].

Transformer-Based Models: Adapt natural language processing architectures to handle chemical representations (e.g., SMILES strings, molecular graphs), using attention mechanisms to focus on critical substructures or interactions [7].

Generative Models: Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) enable de novo drug design by generating novel molecular structures with desired properties, exploring vast chemical spaces beyond existing compound libraries [7].

AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening Platforms

Integrated AI platforms are transforming virtual screening pipelines through unified workflows that combine multiple methodologies:

DrugCLIP: An AI-driven ultra-high-throughput virtual screening platform developed by Tsinghua University and the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence represents next-generation screening systems capable of evaluating unprecedented compound libraries [8].

Automated Protocol Pipelines: Recent publications describe comprehensive automated virtual screening pipelines that include library generation, docking evaluation, and results ranking, providing researchers with streamlined workflows that lower access barriers to advanced structure-based drug discovery [9].

Table 2: AI/ML Algorithms in Virtual Screening

| Algorithm Category | Specific Methods | Virtual Screening Applications | Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Machine Learning | Random Forest, SVM, Decision Trees | QSAR modeling, classification, docking rescoring | 20% improvement in enrichment factors; reduced false positives |

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Binding affinity prediction, molecular property estimation | Superior performance in capturing structural relationships |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | 3D structure analysis, protein-ligand interaction prediction | High accuracy in spatial interaction modeling |

| Deep Learning | Transformers | Molecular generation, property prediction, quantum computations | Parallel processing with attention mechanisms |

| Generative Models | VAEs, GANs | De novo molecular design, chemical space exploration | Novel compound generation with optimized properties |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section provides detailed protocols for implementing virtual screening workflows, combining established docking procedures with emerging AI-enhanced methodologies.

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening with DOCK 6.12

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive structure-based virtual screening pipeline using DOCK 6.12, demonstrated with the Catalytic Domain of Human Phosphodiesterase 4B in Complex with Roflumilast (PDB Code: 1XMU) [6].

Structure Preparation

Objectives: Prepare protein receptor and ligand structures in appropriate formats with added hydrogen atoms and assigned charges.

Protein Receptor Preparation:

- Obtain protein structure from RCSB PDB database (1XMU.pdb).

- Remove native ligand and water molecules using Chimera: Select → residue → ligand → Actions → Atoms/Bonds → Delete.

- Save processed protein without charges and hydrogens as 1XMURecnCH.mol2.

- Add hydrogen atoms: Tools → Structure Editing → AddH.

- Assign partial charges: Tools → Structure Editing → Add Charge → Gasteiger charges.

- Save final prepared receptor as 1XMURecwCH.mol2.

Ligand Preparation:

- Isolate native ligand from original PDB structure.

- Remove all non-ligand atoms: Select → residue → ligand → Select → Invert → Actions → Atoms/Bonds → Delete.

- Save initial ligand as 1XMUlignCH.mol2.

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign Gasteiger charges as described for protein preparation.

- Save final prepared ligand as 1XMUligwCH.mol2.

Alternative Unified Preparation: Utilize Chimera's Dock Prep tool (Tools → Structure Editing → Dock Prep) for streamlined preparation of both receptor and ligand in a single workflow.

Surface and Sphere Generation

Objectives: Generate molecular surface and binding site spheres to define the search space for docking calculations.

Surface Generation:

- Open prepared receptor file (1XMURecnCH.pdb) in Chimera.

- Generate molecular surface: Actions → Surface → Show.

- Create DMS file: Tools → Structure Editing → Write DMS → Save as 1XMU_surface.dms.

Sphere Generation:

- Create INSPH input file containing:

- Execute sphere generation:

sphgen -i INSPH -o OUTSPH - Select binding site spheres:

sphere_selector 1XMU.sph ../001.structure/1XMU_lig_wCH.mol2 10.0

Grid Generation and Docking Calculations

Grid Generation:

- Define grid volume encompassing binding site spheres.

- Generate scoring grid using grid utility with the following parameters:

- Grid spacing: 0.3 Ã…

- Energy cutoff: 1000.0

- Distance from sphere set: 1.0 Ã…

Docking Execution:

- Prepare compound library in mol2 format with assigned charges.

- Configure docking parameters:

- Ligand flexibility: Bond rotations allowed

- Anchor orientation: 1000 orientations

- Maximum iterations: 100

- Execute virtual screening:

dock6 -i dock.in -o dock.out - Process results to extract top-ranking poses for further analysis.

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening with Machine Learning Rescoring

This protocol enhances traditional docking through machine learning-based rescoring to improve binding affinity predictions and hit enrichment.

Training Dataset Curation

- Collect Bioactivity Data: Extract protein-ligand complexes with known binding affinities (IC50, Ki, Kd) from public databases (PDBbind, ChEMBL, PubChem).

- Generate Molecular Descriptors: Calculate comprehensive descriptor sets including:

- 2D molecular descriptors (molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors)

- 3D pharmacophoric features

- Interaction fingerprint vectors from docking poses

- Dataset Partitioning: Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets maintaining temporal or structural clustering to prevent data leakage.

Machine Learning Model Development

- Feature Selection: Apply recursive feature elimination or tree-based importance ranking to identify most predictive descriptors.

- Model Training: Implement multiple algorithm types:

- Random Forest regression for binding affinity prediction

- Support Vector Machine classification for active/inactive binary categorization

- Gradient Boosting machines for non-linear relationship modeling

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Conduct grid search or Bayesian optimization with cross-validation to maximize predictive performance.

- Model Validation: Evaluate using test set with metrics including:

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for regression tasks

- Area Under ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) for classification tasks

- Enrichment Factors (EF1, EF10) for virtual screening performance

Integration with Docking Workflow

- Initial Docking: Perform traditional molecular docking of compound library.

- Descriptor Generation: Compute ML model features for all docking poses.

- ML Rescoring: Apply trained model to generate improved binding scores.

- Result Integration: Combine ML scores with traditional scoring functions using weighted averaging.

- Hit Selection: Prioritize compounds based on consensus ranking from multiple scoring approaches.

Successful implementation of virtual screening protocols requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details essential components of a virtual screening research infrastructure.

Table 3: Essential Virtual Screening Research Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Application in Virtual Screening | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking Software | DOCK 6.12, AutoDock Vina | Structure-based screening, pose prediction | Flexible ligand handling, scoring functions, grid-based docking |

| Structure Preparation | UCSF Chimera | Protein and ligand preparation, surface generation | Add hydrogens, assign charges, visual validation |

| AI/ML Platforms | DrugCLIP, TensorFlow, PyTorch | AI-enhanced screening, predictive modeling | Ultra-high-throughput capability, neural network architectures |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, ChEMBL, Enamine | Source of screening compounds | Millions of purchasable compounds, annotated bioactivities |

| Computing Infrastructure | Linux Clusters, HPC Systems | Parallel processing of large libraries | Batch queue systems (Sun Grid Engine, Torque PBS) |

| Visualization & Analysis | ChemVA, Molecular Architect | Results interpretation, chemical space analysis | Dimensionality reduction, interactive similarity mapping |

Workflow Visualization and Decision Pathways

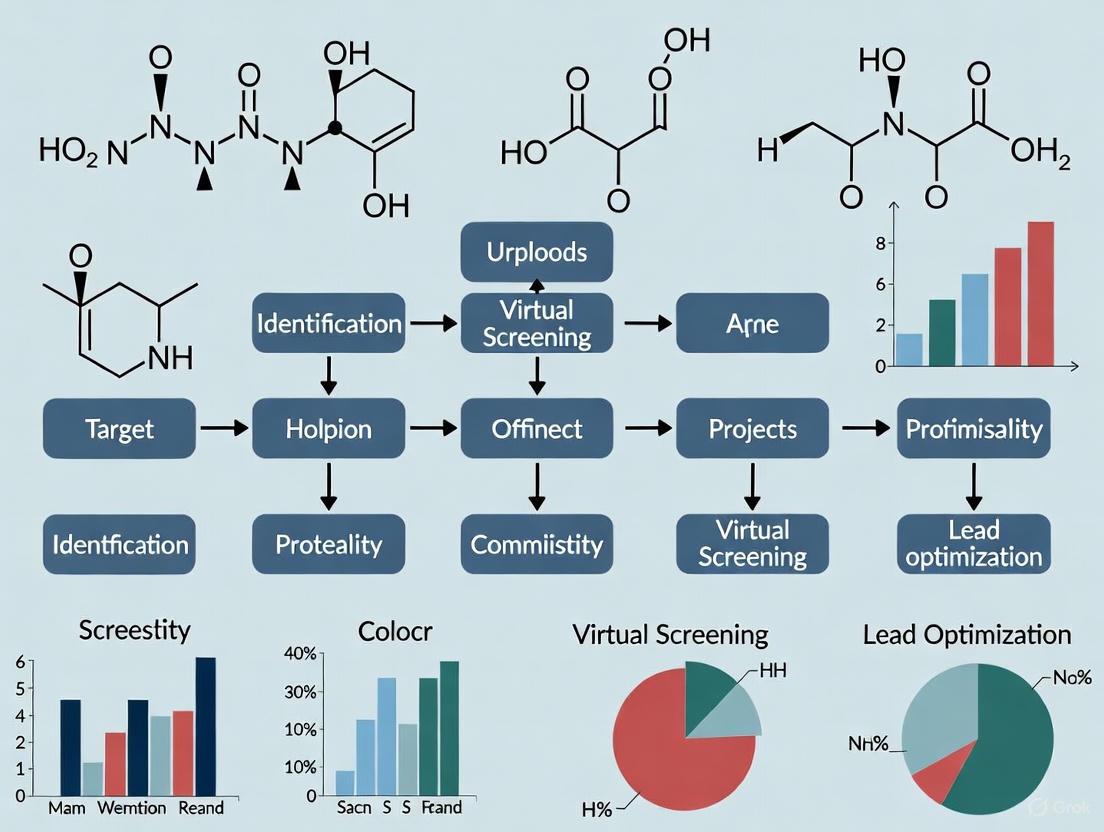

The following diagram illustrates the integrated virtual screening workflow, combining traditional and AI-enhanced approaches:

Virtual Screening Workflow Decision Pathway

The workflow diagram above outlines the strategic decision points in virtual screening implementation. Researchers begin with input data assessment, then select the optimal screening approach based on available structural and ligand information. Structure-based and ligand-based paths converge at the AI rescoring stage, where machine learning models enhance prediction accuracy before final hit selection and experimental validation.

Virtual screening has evolved from traditional docking approaches reliant on geometric complementarity to sophisticated AI-driven paradigms that leverage deep learning and predictive modeling. This progression has substantially enhanced the efficiency, accuracy, and scope of computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to navigate exponentially expanding chemical spaces while reducing reliance on resource-intensive experimental screening.

The integration of AI technologies represents a transformative advancement, with machine learning algorithms now capable of improving enrichment factors by up to 20% compared to conventional methods [7]. Emerging platforms like DrugCLIP demonstrate the potential for ultra-high-throughput screening at unprecedented scales, while automated protocol pipelines lower accessibility barriers for researchers implementing structure-based drug discovery [9] [8]. These developments collectively address critical bottlenecks in pharmaceutical development, including the 90% failure rate of clinical trial candidates and the $2.6 billion average cost per approved drug [5].

As virtual screening methodologies continue to advance, the convergence of physical simulation principles with data-driven AI approaches promises to further enhance predictive accuracy and chemical space exploration. Researchers are encouraged to adopt integrated workflows that combine established docking protocols with AI rescoring and validation frameworks, leveraging the complementary strengths of both paradigms to maximize hit discovery efficiency in targeted therapeutic development.

Application Notes & Protocols

For Drug Discovery Research

Virtual screening (VS) has become a cornerstone in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to rapidly identify potential drug candidates from vast compound libraries before committing to costly and time-consuming laboratory testing [10]. As a computational approach, VS leverages hardware and software to analyze molecular interactions, utilizing algorithms like molecular docking and machine learning models to predict compound activity [10]. However, despite its widespread adoption, several persistent challenges impact the accuracy, efficiency, and reliability of virtual screening protocols. This document, framed within a broader thesis on virtual screening for drug discovery, addresses three critical contemporary challenges: scoring functions, data management, and experimental validation. It provides application notes and detailed protocols to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate these complexities and enhance their VS workflows.

Challenge 1: Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are mathematical algorithms used to predict the binding affinity between a ligand and a target protein. Their limitations in accuracy and high false-positive rates represent a significant bottleneck in virtual screening [11].

Current Limitations and Advanced Approaches

Traditional scoring functions often struggle with accuracy and yield high false-positive rates [11]. Contemporary research focuses on integrating machine learning (ML) and heterogeneous data to improve predictive performance.

SCORCH2: A Heterogeneous Consensus Model A leading-edge approach, SCORCH2, is a machine-learning framework designed to enhance virtual screening performance by using interaction features [12]. Its methodology involves:

- Architecture: Utilizes two distinct XGBoost models trained on separate datasets for heterogeneous consensus scoring [12].

- Feature Engineering: Generates features from multiple sources, including BINANA and ECIF (which extract conformation-sensitive features) and RDKit (which provides conformation-independent features) [12].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Employs Optuna to maximize the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUCPR), which is particularly suited for imbalanced datasets common in VS [12].

- Weighted Consensus: For final prediction, a weighted consensus is derived from the maximum-scoring pose of a compound [12].

This model has demonstrated superior performance and robustness on the DEKOIS 2.0 benchmark, including on subsets with unseen targets, highlighting its strong generalization capability [12].

Integration of ML-Based Pose Sampling Another advancement involves combining ML-based pose sampling methods with established scoring functions. For instance, integrating DiffDock-L (an ML-based pose sampling method) with traditional scoring functions like Vina and Gnina has shown competitive virtual screening performance and high-quality pose generation in cross-docking settings [13]. This approach establishes ML-based methods as a viable alternative or complement to physics-based docking algorithms.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Scoring Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of different scoring approaches based on benchmark studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods on DEKOIS 2.0 Benchmark

| Method | Core Principle | Reported Performance Advantage | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCORCH2 [12] | ML-based heterogeneous consensus (XGBoost) | Outperforms previous docking/scoring methods; strong generalization to unseen targets | High explainability via SHAP analysis; models general molecular interactions |

| DiffDock-L + Vina/Gnina [13] | ML-based pose sampling with classical scoring | Competitive VS performance and pose quality in cross-docking | Physically plausible and biologically relevant poses; viable alternative to physics-based docking |

| Classical Physics-Based Docking (e.g., AutoDock Vina) [13] | Physics-based force fields and scoring | Baseline for comparison | Well-established, interpretable |

Challenge 2: Data Management

Virtual screening involves processing massive compound libraries, often containing millions to billions of structures, which poses significant computational challenges for data storage, processing, and analysis [11].

Protocol for Managing Large-Scale Virtual Screening Data

Objective: To efficiently manage and process large compound libraries for a virtual screening campaign. Materials: High-performance computing servers (CPUs/GPUs), cloud computing resources, chemical database files (e.g., SDF, SMILES), data management software/scripts.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Data Management

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Servers (GPU/CPU) [10] | Handles complex calculations and parallel processing of large datasets. |

| Cloud Computing Platforms [10] | Provides scalable infrastructure, reducing costs and increasing throughput. |

| Standardized File Formats (e.g., SBML) [10] | Ensures interoperability and seamless data exchange between software platforms. |

| Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) [10] | Enables automation and integration with other databases and laboratory instruments. |

| Collaborative Databases (e.g., CDD Vault) [14] | Supports protocol setup, assay data organization, and links experimental systems with data management workflows. |

Procedure:

- Library Preparation and Curation:

- Acquire compound libraries from public or commercial sources.

- Perform standard cheminformatics curation: remove duplicates, neutralize charges, and generate plausible tautomers and protonation states at biological pH.

- Filter structures based on drug-likeness or lead-likeness rules and structural alerts.

Structural Filtration:

- Apply structural filtration to remove compounds with unfavorable properties for target binding, such as inappropriate size, undesirable functional groups, or an inability to form required interactions with the protein target [11].

- This step significantly reduces the library size for subsequent, more computationally intensive docking.

Workflow Automation and Distributed Computing:

- Use workflow management tools to automate the screening pipeline.

- Distribute the curated library across available computational nodes (on-premises or cloud).

- Execute molecular docking or other screening methods in parallel to maximize throughput.

Data Integration and Analysis:

- Collect all output data (scores, poses, interaction fingerprints) into a centralized, searchable database.

- Integrate results with other data sources, such as historical screening data or predicted ADMET properties.

- Perform triage and hit selection based on consensus scores and interaction patterns.

Diagram 1: Data Management and VS Workflow

Challenge 3: Experimental Validation

The ultimate test of any virtual screening campaign is the experimental confirmation of predicted activity. This step is crucial but often expensive and time-consuming, creating a need for more efficient validation methods [11].

Protocol for Multi-Step Validation of Virtual Screening Hits

Objective: To establish a rigorous, tiered protocol for experimentally validating hits identified through virtual screening. Materials: Predicted hit compounds, target protein, cell lines relevant to the disease model, assay reagents, instrumentation for readout.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Experimental Validation

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Purified Target Protein | Required for in vitro binding and activity assays. |

| Relevant Cell Lines (e.g., Vero-E6, Calu-3) [11] | Essential for cell-based assays; choice of model impacts results (e.g., antiviral drug efficacy is variant- and cell-type-dependent). |

| In Vitro Assay Kits (e.g., binding, enzymatic activity) | Provide standardized methods for initial activity confirmation. |

| Compounds for Positive/Negative Controls | Validate assay performance and serve as benchmarks for hit activity. |

Procedure:

- In Vitro Binding or Functional Assay:

- Purpose: Primary confirmation of target engagement and functional activity.

- Method: Test the top-priority virtual screening hits in a biochemical assay. This could be a direct binding assay or a functional assay measuring enzyme inhibition or receptor antagonism/agonism.

- Execution: Use a dose-response design to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration and confirm dose dependency.

Cell-Based Efficacy and Cytotoxicity Assay:

- Purpose: To confirm activity in a more physiologically relevant environment and assess preliminary cytotoxicity.

- Method: Treat disease-relevant cell models with the confirmed hits.

- Execution:

- Measure the desired therapeutic effect.

- Perform a parallel cell viability assay to identify compounds with cytotoxic effects at the tested concentrations.

- Critical Note: The choice of cell model is crucial, as drug efficacy can be cell-type-dependent, as demonstrated for antimalarials against different SARS-CoV-2 variants [11].

Selectivity and Counter-Screening:

- Purpose: To ensure hits are not promiscuous binders or interfering with related but undesired targets.

- Method: Counter-screen confirmed active compounds against a panel of related targets.

Advanced Computational Validation:

- Purpose: To refine the hit list before or in parallel with experimental validation, increasing the success rate.

- Methods:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Run simulations (e.g., 100-300 ns) of the top-ranked protein-ligand complexes to assess binding stability and key interactions over time [11].

- MM-PBSA/GBSA Calculations: Use the MD trajectories to calculate more rigorous binding free energies, which can correlate better with experimental affinity than docking scores alone [11].

Diagram 2: Multi-Step Hit Validation Protocol

The integration of advanced machine learning models like SCORCH2 for scoring, robust protocols for managing large datasets, and a multi-faceted approach to experimental validation collectively address the key challenges in contemporary virtual screening. As the field moves forward, the increased use of AI, cloud computing, and standardized, interoperable workflows will be crucial for improving the predictive accuracy and efficiency of virtual screening, ultimately accelerating the discovery of new therapeutics [10] [11]. The protocols and application notes detailed herein provide a practical framework for researchers to enhance their virtual screening campaigns within the broader context of modern drug discovery research.

The concept of "chemical space" is fundamental to modern drug discovery, representing the multi-dimensional property space spanned by all possible molecules and chemical compounds adhering to specific construction principles and boundary conditions [15]. This theoretical space is astronomically large, with estimates suggesting approximately 10^60 pharmacologically active molecules exist, though only a minute fraction has been synthesized and characterized [15]. As of October 2024, only about 219 million molecules had been assigned Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) Registry Numbers, highlighting the largely unexplored nature of this domain [15].

The systematic exploration of this chemical universe has become a critical capability in early drug discovery, where the identification of novel chemical leads against biological targets of interest remains a fundamental challenge. With the advent of readily accessible chemical libraries containing billions of compounds, researchers now face both unprecedented opportunities and significant computational challenges in effectively navigating this expansive territory [16]. Virtual screening has emerged as a key methodology to address this challenge, leveraging computational power to identify promising compounds for further development and refinement from these ultra-large libraries.

The Computational Challenge of Ultra-Large Libraries

The Scale Problem in Virtual Screening

Traditional virtual screening approaches face significant challenges when applied to billion-compound libraries. Physics-based docking methods, while accurate, become prohibitively time-consuming and computationally expensive at this scale [16]. Screening an entire ultra-large library using conventional methods requires immense computational resources that may be impractical for many research institutions.

The fundamental challenge lies in the success of virtual screening campaigns depending crucially on two factors: the accuracy of predicted binding poses and the reliability of binding affinity predictions [16]. While leading physics-based ligand docking programs like Schrödinger Glide and CCDC GOLD offer high virtual screening accuracy, they are often not freely available to researchers, creating accessibility barriers [16]. Although open-source options like AutoDock Vina are widely used, they typically demonstrate slightly lower virtual screening accuracy compared to commercial alternatives [16].

Emerging Solutions for Scalable Screening

Recent advances have introduced several strategies to overcome these scalability challenges:

- AI-Accelerated Platforms: New open-source platforms like OpenVS use active learning techniques to train target-specific neural networks during docking computations, efficiently selecting promising compounds for expensive docking calculations [16].

- Hierarchical Screening: Multi-tiered approaches that combine fast initial filters with more precise secondary screening [16].

- GPU Acceleration: Leveraging graphics processing units to dramatically speed up docking calculations [16].

- High-Performance Computing: Utilizing parallelization on HPC clusters to distribute computational load [16].

These approaches have demonstrated practical utility, with recent studies completing screening of multi-billion compound libraries in less than seven days using local HPC clusters equipped with 3000 CPUs and one RTX2080 GPU per target [16].

Benchmarking Virtual Screening Performance

Quantitative Metrics for Evaluation

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating virtual screening methods. Standardized datasets and metrics enable quantitative comparison of different approaches. Key benchmarks include:

Table 1: Key Benchmarking Metrics for Virtual Screening Methods

| Metric | Description | Application | Optimal Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Power | Ability to identify native binding poses from decoy structures | CASF-2016 benchmark with 285 protein-ligand complexes | Higher accuracy indicates better performance [16] |

| Screening Power | Capability to identify true binders among negative molecules | Measured via Enrichment Factor (EF) and success rates | EF1% = 16.72 for top-performing methods [16] |

| Binding Funnel Analysis | Efficiency in driving conformational sampling toward lowest energy minimum | Assesses performance across ligand RMSD ranges | Broader funnels indicate more efficient search [16] |

| Z-factor | Measure of assay robustness and quality control in HTS | Used in experimental validation of virtual hits | Values >0.5 indicate excellent assays [17] |

| Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) | Method for assessing data quality in HTS assays | More robust than Z-factor for some applications | Better captures effect sizes for hit selection [17] |

Performance of State-of-the-Art Methods

Recent advances have yielded significant improvements in virtual screening capabilities. The RosettaVS method, based on an improved RosettaGenFF-VS force field, has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on standard benchmarks [16]. Key achievements include:

- Superior Docking Accuracy: Outperforms other methods in correctly identifying native binding poses from decoy structures [16].

- Enhanced Screening Power: Achieves an enrichment factor (EF1%) of 16.72, significantly outperforming the second-best method (EF1% = 11.9) [16].

- Effective Handling of Receptor Flexibility: Accommodates full flexibility of receptor side chains and partial flexibility of the backbone, critical for modeling induced conformational changes upon ligand binding [16].

These improvements are particularly evident in challenging scenarios involving more polar, shallower, and smaller protein pockets, where traditional methods often struggle [16].

Experimental Protocols for Billion-Compound Screening

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening Workflow

Protocol 1: Hierarchical Screening of Ultra-Large Libraries

Objective: To efficiently screen multi-billion compound libraries using a tiered approach that balances computational efficiency with accuracy.

Materials:

- Target protein structure (experimental or homology model)

- Billion-compound library in appropriate format (e.g., SDF, SMILES)

- High-performance computing cluster (3000+ CPUs, GPU acceleration)

- OpenVS platform or similar virtual screening software [16]

Procedure:

- Library Preparation (Time: 2-4 hours)

- Convert compound libraries to uniform format

- Apply standard pre-processing: desalting, tautomer standardization, protonation state adjustment

- Filter using drug-like properties (Lipinski's Rule of Five, molecular weight <500 Da)

Initial Rapid Screening (Time: 1-2 days)

- Use express docking mode (VSX) for initial pass

- Employ active learning to train target-specific neural network

- Screen ~1% of library (10 million compounds) initially

- Select top 0.1% (10,000 compounds) for secondary screening

High-Precision Docking (Time: 3-4 days)

- Apply high-precision mode (VSH) with full receptor flexibility

- Use RosettaGenFF-VS scoring function combining enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) terms

- Generate binding poses and affinity predictions for top candidates

Hit Selection and Prioritization (Time: 1 day)

- Apply compound clustering to ensure structural diversity

- Evaluate synthetic accessibility and potential toxicity

- Select 100-500 compounds for experimental validation

Validation: In recent implementations, this protocol identified 7 hits (14% hit rate) for KLHDC2 and 4 hits (44% hit rate) for NaV1.7, all with single-digit micromolar binding affinities [16].

Experimental Validation of Virtual Hits

Protocol 2: Confirmatory Screening of Virtual Screening Hits

Objective: To experimentally validate computational predictions using biochemical and biophysical assays.

Materials:

- Purified target protein

- Virtual screening hit compounds

- Appropriate assay reagents and plates (96, 384, or 1536-well format)

- High-throughput screening instrumentation [17]

Procedure:

- Compound Management

- Prepare mother plates (10 mM DMSO stock solutions)

- Create daughter plates for assay distribution

- Implement proper quality control (QC) measures

Assay Development

- Establish robust assay conditions with appropriate controls

- Determine Z-factor (>0.5 indicates excellent assay quality) [17]

- Optimize reagent concentrations and incubation times

Dose-Response Testing

- Test compounds across a range of concentrations (typically 0.1 nM - 100 μM)

- Generate concentration-response curves

- Calculate IC50/EC50 values

Counter-Screening and Selectivity Assessment

- Test against related targets to assess selectivity

- Perform promiscuity assays to identify pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS)

Quality Control: Implement strict QC measures using positive and negative controls, with statistical assessment via Z-factor or SSMD metrics [17].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Billion-Compound Screening Workflow

Virtual Screening Workflow for Ultra-Large Libraries

Chemical Space Navigation Strategy

Chemical Space Navigation from Theory to Lead Compounds

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | GDB-17 (166 billion molecules), ZINC (21 million), PubChem (32.5 million) | Source of virtual compounds for screening | Public access [18] [15] |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | OpenVS, RosettaVS, AutoDock Vina | Docking and screening computation | Open source [16] |

| Chemical Descriptors | Molecular Quantum Numbers (MQN, 42 descriptors) | Chemical space mapping and compound classification | Public method [18] |

| Benchmarking Datasets | CASF-2016 (285 complexes), DUD (40 targets) | Method validation and performance assessment | Public access [16] |

| Experimental HTS Infrastructure | Microtiter plates (96-6144 wells), liquid handling robots, detection systems | Experimental validation of virtual hits | Commercial/institutional [17] |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL (2.4+ million molecules), BindingDB (360,000 molecules) | Known bioactivity data for validation | Public access [18] |

Case Studies and Applications

Successful Implementation Examples

Recent applications demonstrate the practical utility of advanced virtual screening approaches:

Case Study 1: KLHDC2 Ubiquitin Ligase Target

- Screening Scale: Multi-billion compound library

- Method: RosettaVS with flexible receptor docking

- Results: 7 hit compounds identified (14% hit rate) with single-digit μM binding affinity

- Validation: High-resolution X-ray crystallography confirmed predicted docking pose [16]

Case Study 2: NaV1.7 Sodium Channel Target

- Screening Scale: Multi-billion compound library

- Method: OpenVS platform with active learning

- Results: 4 hit compounds identified (44% hit rate) with single-digit μM binding affinity

- Timeline: Complete screening process in under 7 days [16]

These case studies highlight the potential for structure-based virtual screening to identify novel chemical matter even for challenging targets, with hit rates substantially higher than traditional high-throughput screening approaches.

The field of virtual screening continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future development:

- AI and Machine Learning Integration: Enhanced predictive accuracy through deep learning models trained on increasingly large datasets [10]

- Cloud Computing and Scalability: Broader access to computational resources through cloud-based screening platforms [10]

- Hybrid Approaches: Combination of physical docking with machine learning prioritization for optimal efficiency and accuracy [16]

- Standardization and Benchmarking: Development of more rigorous validation standards to assess method performance [16]

The expanding chemical space represents both a formidable challenge and tremendous opportunity for drug discovery. By leveraging advanced computational methods, hierarchical screening protocols, and appropriate validation strategies, researchers can effectively navigate billion-compound libraries to identify novel lead compounds with unprecedented efficiency. The integration of these virtual screening approaches with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for accelerating early drug discovery and exploring the vast untapped potential of chemical space.

Virtual screening (VS) has become a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling the computational identification of potential drug candidates from vast compound libraries [11]. The success of VS heavily relies on the integrated application of several core computational components, each addressing a distinct challenge in the prediction of biological activity and drug-like properties [11] [19]. This document details the essential protocols for implementing three pillars of a robust virtual screening pipeline: scoring algorithms for binding affinity prediction, structural filtration to prioritize specific protein-ligand interactions, and physicochemical property prediction to ensure favorable pharmacological profiles [11]. The methodologies outlined herein are designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the efficiency and success rate of their hit identification and lead optimization campaigns.

Core Components & Quantitative Benchmarks

Performance Metrics of Virtual Screening Components

The following table summarizes the key components and their reported performance in enhancing virtual screening campaigns.

Table 1: Key Components and Performance in Virtual Screening

| Component | Primary Function | Key Metric/Performance | Impact on Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scoring Algorithms [20] | Predict ligand conformation and binding affinity to a target. | Imperfect accuracy; high false positive rates remain a major limitation [11]. | Foundation of structure-based screening; accuracy limits overall success. |

| Structural Filtration [21] | Filter docking poses based on key, conserved protein-ligand interactions. | Improved enrichment factors from several-fold to hundreds-fold; considerably lower false positive rate [21]. | Effectively removes false positives and repairs scoring function deficiencies. |

| Physicochemical/ADMET Prediction [11] | Predict solubility, permeability, metabolism, and toxicity. | Enables early assessment of drug-likeness; prevents late-stage failures due to poor properties [11]. | Crucial for prioritizing compounds with a higher probability of becoming viable drugs. |

| Machine Learning-Guided Docking [22] | Accelerate ultra-large library screening by predicting docking scores. | ~1000-fold reduction in computational cost; identifies >87% of top-scoring molecules by docking only ~10% of the library [22]. | Makes screening of billion-membered chemical libraries computationally feasible. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Structural Filtration Workflow

Structural filtration is a powerful post-docking step that selects ligand poses based on their ability to form specific, crucial interactions with the protein target, thereby significantly improving hit quality [21].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Structural Filtration

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | The 3D atomic coordinates of the target, ideally with a known active ligand. | PDB ID: 7LD3 (Human A1 Adenosine Receptor) [11]. |

| Docked Ligand Poses | The raw output from a molecular docking simulation. | Output from docking software (e.g., Lead Finder [21]). |

| Structural Filter | A user-defined set of interaction rules critical for binding. | A set of interactions (e.g., H-bond with residue Asp-101, hydrophobic contact with residue Phe-201) [21]. |

| Automation Tool | Software to apply the filter to large libraries of docked poses. | vsFilt web-server [23]. |

| Interaction Detection | Algorithm to identify specific protein-ligand interaction types. | Detection of H-bonds, halogen bonds, ionic interactions, hydrophobic contacts, π-stacking, and cation-π interactions [23]. |

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Methodology

Define the Structural Filter:

- Source: Analyze multiple available crystal structures of your target protein in complex with its known active ligands (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank).

- Identification: Identify a set of interactions that are structurally conserved across these complexes. These typically play a crucial role in molecular recognition and binding [21].

- Rule Definition: Formally define these interactions as filtering rules. For example: "Ligand must form a hydrogen bond with the side chain of residue HIS72" and "Ligand must engage in a hydrophobic contact with the aliphatic chain of residue LEU159" [23].

Generate Docked Poses:

- Perform a virtual screen of your compound library against the prepared protein structure using your chosen molecular docking software (e.g., Lead Finder, Glide, AutoDock) to generate a set of docked poses for each compound [21].

Apply the Structural Filter:

- Tool: Use a specialized tool like the vsFilt web-server to process the raw docking output [23].

- Input: Provide the file containing the docked poses and the file defining your structural filter rules.

- Execution: The tool will automatically evaluate each pose and retain only those that comply with all the user-defined interaction rules.

Analysis and Hit Selection:

- The filtered list of compounds is significantly enriched with true binders. These can be prioritized for further analysis, scoring, and experimental validation [21].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-step protocol for structural filtration:

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Screening of Ultra-Large Libraries

Conventional docking becomes computationally prohibitive for libraries containing billions of compounds. This protocol uses machine learning (ML) to rapidly identify a small, high-potential subset for explicit docking [22] [24].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for ML-Guided Screening

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Large Chemical Library | A make-on-demand database of synthetically accessible compounds. | Enamine REAL Space (Billions of compounds) [22]. |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of chemical structures for ML. | Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP4), CDDD descriptors [22]. |

| ML Classifier | An algorithm trained to predict high-scoring compounds. | CatBoost (demonstrates optimal speed/accuracy balance) [22]. |

| Conformal Prediction Framework | A method to control the error rate of ML predictions and define the virtual active set. | Mondrian Conformal Predictor [22]. |

| Docking Program | Software for final structure-based evaluation of the ML-selected subset. | Any conventional docking program (e.g., AutoDock, Glide) [24]. |

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Methodology

Initial Random Sampling & Docking:

- Randomly select a representative subset (e.g., 1 million compounds) from the multi-billion-member library [22].

- Dock this entire subset against the target protein using your standard docking protocol to generate a set of labeled training data (structures paired with docking scores).

Machine Learning Model Training:

- Feature Generation: Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) for all compounds in the training set.

- Labeling: Define an activity threshold (e.g., top 1% of docking scores) to label compounds as "virtual active" or "virtual inactive" [22].

- Training: Train a classifier (e.g., CatBoost) on this data to learn the structural patterns that differentiate high-scoring from low-scoring compounds.

ML Prediction and Library Reduction:

- Use the trained model to predict the likelihood of activity for the entire ultra-large library (billions of compounds). This step is computationally cheap compared to docking.

- Apply the conformal prediction framework to select a "virtual active" set from the large library. The user can control the error rate, which in turn determines the size of this subset [22].

Final Docking and Validation:

- Dock only the ML-predicted "virtual active" set (e.g., ~10% of the original library) using conventional docking.

- Experimental testing of the top-ranking molecules from this final docked set validates the workflow and identifies true ligands [22].

The iterative workflow for this protocol is shown below:

Integrated Workflow & Case Studies

Synergistic Application in a Virtual Screening Campaign

The true power of these components is realized when they are integrated into a sequential workflow. A typical pipeline begins with an ML-guided rapid screen of an ultra-large library to reduce its size, followed by conventional docking of the enriched subset. The resulting poses are then subjected to structural filtration to select only those that form key interactions, and finally, the top hits are evaluated based on predicted physicochemical and ADMET properties to ensure drug-like qualities [11] [19] [22]. This multi-stage approach maximizes both computational efficiency and the probability of identifying viable lead compounds.

Case Study: Identification of Kinase and GPCR Ligands

A recent study demonstrated the application of an ML-guided docking workflow, screening a library of 3.5 billion compounds [22]. The protocol, which used the CatBoost classifier and conformal prediction, achieved a computational cost reduction of more than 1,000-fold. Experimental testing of the predictions successfully identified novel ligands for G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), a therapeutically vital protein family. This case validates the protocol's ability to discover active compounds with multi-target activity tailored for therapeutic effects from an unprecedentedly large chemical space [22].

The integration of advanced computational and experimental methods is fundamental to modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to navigate the complexities of biological systems and chemical space efficiently. Virtual screening (VS) has emerged as a pivotal tool in early discovery phases, allowing for the rapid evaluation of vast compound libraries to identify potential drug candidates [11]. However, the success of virtual screening hinges on its strategic positioning within a broader pipeline and the optimal utilization of resources to overcome inherent challenges such as scoring function accuracy, structural filtration, and the management of large datasets [11]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for integrating and optimizing virtual screening within drug discovery pipelines, providing researchers with actionable methodologies and frameworks.

Virtual screening performance is influenced by several technical challenges that impact both its efficiency and the reliability of its results. The quantitative scope of these challenges is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key challenges in virtual screening and their implications for drug discovery pipelines.

| Challenge | Quantitative Impact & Description | Strategic Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Scoring Functions | Limitations in accuracy and high false positive rates [11]. | Crucial for distinguishing true binders from non-binders; impacts downstream validation costs. |

| Structural Filtration | Removes compounds with undesirable structures (e.g., too large, wrong functional groups) [11]. | Reduces the number of compounds for expensive docking calculations, optimizing computational resources. |

| Physicochemical/Pharmacological Prediction | Predicts properties such as solubility, permeability, metabolism, and toxicity [11]. | Enables early assessment of drug-likeness and developability, reducing late-stage attrition. |

| Large Dataset Management | Involves screening libraries containing millions to billions of compounds [11] [16]. | Requires significant computational infrastructure and efficient data handling pipelines. |

| Experimental Validation | Expensive and time-consuming, though crucial for confirming activity [11]. | A well-optimized VS pipeline enriches the hit rate, making experimental follow-up more cost-effective. |

Integrated Virtual Screening Protocol

This section provides a detailed, sequential protocol for conducting an integrated virtual screening campaign, from target preparation to experimental validation.

Target Selection and Preparation

Objective: To select a therapeutically relevant, druggable target and prepare its structure for virtual screening.

- Target Identification & Validation: Begin with a hypothesis that modulation of a specific protein or pathway will yield a therapeutic effect in a disease. Use genetic associations (e.g., polymorphisms linked to disease risk), proteomics, and transcriptomics data to build confidence in the target [25]. Tools like monoclonal antibodies or siRNA can be used for experimental validation in cellular or animal models [25].

- Structure Acquisition: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). If an experimental structure is unavailable, utilize protein structure prediction tools.

- Binding Site Definition: Identify the binding site of interest using tools that analyze protein surfaces for cavities. For known binding sites (e.g., orthosteric sites), use coordinates from a relevant co-crystal structure.

- Structure Preparation:

- Add missing hydrogen atoms.

- Assign protonation states to residues like Asp, Glu, His, and Lys at physiological pH (typically 7.4) using molecular visualization software.

- Optimize the hydrogen-bonding network.

- Remove crystallographic water molecules unless they are known to be crucial for ligand binding.

Compound Library Preparation

Objective: To prepare a library of small molecules for screening.

- Library Selection: Source compounds from commercial or open-access libraries (e.g., ZINC, Enamine). The scale can range from focused libraries (thousands) to ultra-large libraries (billions of compounds) [16].

- Structural Curation: Convert the library into a uniform format (e.g., SDF, MOL2). Apply structural filtration rules to remove compounds with undesirable properties, such as pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS), reactive functional groups, or those that violate drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) [11].

- Energy Minimization: Generate realistic 3D conformations for each compound using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF94). This step ensures the starting geometries are chemically sensible before docking.

Virtual Screening Execution: A Multi-Stage Docking Protocol

Objective: To efficiently screen the prepared library against the prepared target to identify high-probability hit compounds.

This protocol utilizes a multi-stage approach to balance computational cost with accuracy, as exemplified by the RosettaVS method [16].

Stage 1: Ultra-Fast Prescreening (VSX Mode)

- Method: Use a fast docking algorithm (e.g., RosettaVS's Virtual Screening Express (VSX) mode or AutoDock Vina) that employs rigid or partially flexible receptor models.

- Execution: Screen the entire ultra-large library. This step is designed for speed to rapidly reduce the library size.

- Output: Retain a subset (e.g., 0.1% - 1%) of the top-ranked compounds based on the docking score for further analysis.

Stage 2: High-Precision Docking (VSH Mode)

- Method: Use a more computationally intensive, high-precision docking method (e.g., RosettaVS's Virtual Screening High-precision (VSH) mode or Schrödinger Glide SP/XP) that accounts for full receptor side-chain flexibility and limited backbone movement [16].

- Execution: Dock the top hits from the VSX stage.

- Output: A refined list of several hundred to a few thousand compounds, ranked using a more robust scoring function.

Stage 3: Binding Affinity and Property Prediction

- Method: Apply advanced scoring functions that combine enthalpy (e.g., from molecular mechanics) and entropy estimates (e.g., from conformational sampling) for final ranking, as with RosettaGenFF-VS [16].

- Execution: For the top-ranked compounds from the VSH stage (e.g., top 100-500), predict key physicochemical and pharmacological properties. Use in silico tools (e.g., SwissADME, pkCSM) to estimate:

- Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET): e.g., solubility, cytochrome P450 inhibition, hERG cardiotoxicity.

- Physicochemical Properties: e.g., LogP, topological polar surface area (TPSA).

- Output: A final, prioritized list of 20-50 compounds that possess not only strong predicted binding affinity but also favorable developability profiles.

Experimental Validation Protocol

Objective: To experimentally confirm the binding and activity of the virtually screened hits.

- Compound Acquisition: Procure the top 10-20 prioritized compounds from a commercial supplier or synthesize them in-house.

- In Vitro Binding Assay:

- Method: Use a biophysical technique such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or a thermal shift assay (e.g., Cellular Thermal Shift Assay, CETSA) to confirm direct binding to the target protein [26].

- Protocol: For CETSA, treat intact cells or lysates with the compound at varying concentrations. Heat the samples to denature proteins. Centrifuge to separate soluble (stable) from insoluble (aggregated) protein. Use Western blot or quantitative mass spectrometry to measure the amount of stabilized target protein remaining in the soluble fraction. A concentration-dependent stabilization of the target indicates direct binding [26].

- Functional Activity Assay:

- Method: Perform a cell-based or biochemical assay to measure the compound's effect on the target's function (e.g., enzyme inhibition, receptor antagonism/agonism).

- Protocol: The specific protocol is target-dependent. For an enzyme, incubate the enzyme with its substrate in the presence or absence of the test compound. Measure the production of the reaction product over time to determine the compound's IC50 value.

- Validation: Compounds that show dose-dependent binding and functional activity in the low micromolar to nanomolar range (e.g., ≤ 10 µM) are considered confirmed hits and can advance to lead optimization [16].

Workflow Visualization of the Integrated Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the sequential stages and decision points of the integrated virtual screening protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of the virtual screening protocol relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources and their functions.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and solutions for an integrated virtual screening pipeline.

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Specific Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Docking & Screening | RosettaVS [16] | Provides VSX (fast) and VSH (high-precision) docking modes for tiered screening. |

| AutoDock Vina [16] | Widely used open-source docking program for initial screening stages. | |

| Schrödinger Glide [16] | High-accuracy commercial docking suite for precise pose and affinity prediction. | |

| AI & Data Infrastructure | NVIDIA BioNeMo [27] | A framework providing pre-trained AI models for protein structure prediction, molecular optimization, and docking. |

| GPU Clusters [28] | Hardware acceleration (e.g., NVIDIA GPUs) for drastically reducing docking and AI model training times. | |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, Enamine | Sources of commercially available compounds for virtual and experimental screening. |

| In Silico ADMET | SwissADME [26] | Web tool for predicting pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and medicinal chemistry friendliness. |

| Experimental Validation | CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [26] | Confirms target engagement of hits in a physiologically relevant cellular context. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Label-free technique for quantifying binding kinetics (Kon, Koff, KD) between the hit and purified target. | |

| 4,5,6,7-Tetrahydrobenzo[d]isoxazol-3-amine | 4,5,6,7-Tetrahydrobenzo[d]isoxazol-3-amine, CAS:1004-64-4, MF:C7H10N2O, MW:138.17 | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Bromo-N-butyl-5-ethoxy-2-nitroaniline | 4-Bromo-N-butyl-5-ethoxy-2-nitroaniline, CAS:1280786-89-1, MF:C12H17BrN2O3, MW:317.183 | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Virtual Screening Methodologies: Structure-Based, Ligand-Based, and AI-Accelerated Approaches

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) is an established computational tool in early drug discovery, designed to identify promising chemical compounds that bind to a therapeutic target protein from large libraries of molecules [29] [30]. The success of SBVS hinges on the accuracy of molecular docking, which predicts the three-dimensional structure of a protein-ligand complex and estimates the binding affinity [31] [30]. A critical challenge in this field is the effective accounting for receptor flexibility, as proteins are dynamic entities whose conformations can change upon ligand binding [30] [32]. The inability to model this flexibility accurately can lead to increased false positives and false negatives in virtual screening campaigns [30]. This protocol article details the methodologies for molecular docking and receptor flexibility modeling, framed within the context of a broader thesis on advancing virtual screening protocols for drug discovery research. We summarize key benchmarking data, provide detailed experimental protocols, and visualize core workflows to equip researchers with the practical knowledge to implement these techniques.

Key Quantitative Benchmarks in Virtual Screening

The performance of virtual screening methods is typically evaluated using standardized benchmarks that assess their docking power (pose prediction accuracy) and screening power (ability to identify true binders). The table below summarizes the performance of various state-of-the-art methods on the CASF2016 benchmark.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods on CASF2016 Benchmark

| Method | Type | Key Feature | Docking Power (Success Rate) | Screening Power (EF1%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RosettaGenFF-VS | Physics-based | Models receptor flexibility & entropy | Leading Performance | 16.72 | [31] |

| VirtuDockDL | Deep Learning (GNN) | Ligand- & structure-based AI screening | N/A | Benchmark Accuracy: 99% (HER2) | [33] |

| Deep Docking | AI-Accelerated | Iterative screening with ligand-based NN | N/A | Enables 100-fold acceleration | [24] |

| AutoDock Vina | Physics-based | Widely used free program | Slightly lower than Glide | ~82% Benchmark Accuracy | [31] [33] |

Abbreviations: EF1%: Enrichment Factor at top 1%; GNN: Graph Neural Network; NN: Neural Network.

Another study benchmarking the deep learning pipeline VirtuDockDL against other tools across multiple targets demonstrated its superior predictive accuracy.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of VirtuDockDL vs. Other Tools

| Computational Tool | HER2 Dataset Accuracy | F1 Score | AUC | Key Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VirtuDockDL | 99% | 0.992 | 0.99 | Graph Neural Network (GNN) |

| DeepChem | 89% | N/A | N/A | Machine Learning Library |

| AutoDock Vina | 82% | N/A | N/A | Traditional Docking |

| RosettaVS | N/A | N/A | N/A | Physics-based, receptor flexibility |

| PyRMD | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ligand-based, no AI integration |

Experimental Protocols for Docking and Flexibility Modeling

The RosettaVS Protocol for Flexible Receptor Docking

The RosettaVS protocol, built upon the improved RosettaGenFF-VS force field, incorporates full receptor flexibility and is designed for screening ultra-large libraries [31]. The protocol involves two distinct operational modes:

- Virtual Screening Express (VSX) Mode: This is a rapid initial screening mode designed for efficiency. It typically involves rigid receptor docking or limited flexibility to quickly scan billions of compounds and identify a subset of potential hits.

- Virtual Screening High-Precision (VSH) Mode: This is a more accurate and computationally intensive method used for the final ranking of top hits identified from the VSX screen. The key differentiator is the inclusion of full receptor flexibility, allowing for the modeling of flexible side chains and limited backbone movement to account for induced fit upon ligand binding [31].

The force field combines enthalpy calculations (ΔH) with a new model estimating entropy changes (ΔS) upon ligand binding, which is critical for accurately ranking different ligands binding to the same target [31].

AI-Accelerated Screening with Active Learning

To manage the prohibitive cost of docking multi-billion compound libraries, the OpenVS platform employs an active learning strategy [31]. The workflow, which can be applied with any conventional docking program, is as follows:

- Molecular and Receptor Preparation: Prepare the 3D structures of the target protein and the chemical library, ensuring correct protonation states and generating relevant tautomers and stereoisomers.

- Random Sampling: Randomly select a small subset (e.g., 1%) of the ultra-large chemical library.

- Ligand Preparation and Docking: Prepare the ligands and dock this subset against the prepared receptor.

- Model Training: Use the docking scores and molecular descriptors/fingerprints of the sampled subset to train a target-specific neural network model.

- Model Inference: Use the trained model to predict the docking scores for the entire, undocked portion of the chemical library.

- Residual Docking: Select the top-ranked compounds based on the model's predictions and subject them to actual docking.

- Iterative Application: Steps 2-6 can be repeated iteratively, with the training set continuously augmented with new docking results, which refines the predictive model in each cycle [24]. This process can achieve up to a 100-fold acceleration in screening [24].

Ensemble Docking for Protein Flexibility

A widely used approach to account for protein flexibility is ensemble docking, which utilizes multiple receptor conformations in docking runs [29] [30]. The protocol involves:

- Conformation Selection: Obtain multiple receptor conformations from different experimental structures (X-ray, NMR) or by sampling structures from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Co-crystal structures with larger ligands often provide better results [29] [30].

- Parallel Docking: Dock the ligand library against each conformation in the ensemble independently.

- Pose Selection: For each ligand, select the best-scoring conformation and pose across the entire ensemble for final ranking [29].

It is noted that using an excessively large number of receptor conformers can increase false positives and computational costs linearly. Machine learning techniques can be employed post-docking to help classify active and inactive compounds and mitigate this issue [29].

Workflow Visualization of Key Protocols

General Workflow for Structure-Based Virtual Screening

The following diagram outlines the standard end-to-end workflow for a structure-based virtual screening campaign, from target identification to experimental validation.

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening with Active Learning

This diagram details the iterative active learning workflow used in platforms like Deep Docking and OpenVS to efficiently screen ultra-large chemical libraries.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for SBVS

| Item / Resource | Type | Function in SBVS | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenVS Platform | Software Platform | Open-source, AI-accelerated virtual screening | Integrates RosettaVS; uses active learning for billion-compound libraries [31]. |

| Deep Docking (DD) | Software Protocol | AI-powered screening acceleration | Can be used with any docking program; enables 100-fold screening speed-up [24]. |

| RosettaVS | Docking Protocol | Physics-based docking with flexibility | Two modes (VSX & VSH); models sidechain/backbone flexibility [31]. |

| VirtuDockDL | Software Platform | Deep learning pipeline for VS | Uses Graph Neural Networks (GNNs); high predictive accuracy [33]. |

| VirtualFlow | Software Platform | Open-source platform for ultra-large VS | Supports flexible receptor docking with GWOVina; linear scaling on HPC [34]. |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Source of commercially available compounds | Contains hundreds of millions of ready-to-dock compounds [29]. |

| Enamine REAL Space | Compound Library | Source of make-on-demand compounds | Ultra-large library (billions of compounds) for expansive chemical space exploration [29]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structural Database | Source of experimental 3D protein structures | Foundational for obtaining target structures for docking [29] [30]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular data processing | Converts SMILES strings to molecular graphs for ML-based VS [33]. |

| GWOVina | Docking Program | Docking with flexibility algorithm | Uses Grey Wolf Optimization for improved flexible receptor docking [34]. |

| 3-(4-methyl benzoyloxy) flavone | 3-(4-methyl benzoyloxy) flavone|CAS 808784-08-9 | Research-grade 3-(4-methyl benzoyloxy) flavone (CAS 808784-08-9). A synthetic flavone derivative for anticancer and antimicrobial studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-(4-Amidinophenoxy)pentanoic Acid | 5-(4-Amidinophenoxy)pentanoic Acid|High Purity | Get high-purity 5-(4-Amidinophenoxy)pentanoic Acid for your research. This compound is For Research Use Only and is not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Within the framework of modern drug discovery, virtual screening (VS) stands as a pivotal computational strategy for identifying potential drug candidates from vast chemical libraries [35]. Ligand-based approaches offer powerful solutions for when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown, but a set of active compounds is available [36] [37]. These methods, primarily pharmacophore modeling and similarity searching, leverage the collective information from known active ligands to guide the selection of new chemical entities with a high probability of bioactivity [38]. The underlying principle, established by Paul Ehrlich and refined over more than a century, is that a pharmacophore represents the "ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [39] [37]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these core ligand-based strategies, enabling researchers to efficiently prioritize compounds for experimental testing.

Theoretical Foundations

The Pharmacophore Concept

A pharmacophore is an abstract model that identifies the essential molecular interaction capabilities required for biological activity, rather than a specific chemical structure [37]. The most critical pharmacophoric features include [39] [36]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) and Donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic (H) and Aromatic (AR)

- Positively (PI) and Negatively (NI) Ionizable groups

These features are represented geometrically in 3D space as spheres, vectors, or planes, with tolerances that define the allowed spatial deviation for a potential ligand [39] [37].

Ligand-Based vs. Structure-Based Approaches

The two primary paradigms for pharmacophore development are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore | Structure-Based Pharmacophore |

|---|---|---|

| Prerequisite | Set of known active ligands [36] [38] | 3D structure of the target protein, often with a bound ligand [39] |

| Methodology | Extraction of common chemical features from aligned active ligands [36] [38] | Analysis of the protein's binding site to derive complementary interaction points [39] |

| Ideal Use Case | Targets lacking 3D structural data [36] [38] | Targets with high-quality crystal structures or reliable homology models [39] |

| Key Advantage | Does not require protein structural data [38] | Can account for specific protein-ligand interactions and spatial restraints from the binding site shape [39] |

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling involves detecting the common functional features and their spatial arrangement shared by a set of active molecules, under the assumption that these commonalities are responsible for their biological activity [36] [38]. The workflow for creating and using such a model is illustrated below.

Diagram 1: Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and screening workflow.

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol details the generation of a pharmacophore model using a set of known active ligands, as implemented in tools such as LigandScout [40] or the OpenCADD pipeline [36].

Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Tools

| Item Name | Type | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|