Mixed Treatment Comparisons and Network Meta-Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mixed treatment comparison (MTC) models, also known as network meta-analysis, a powerful statistical methodology for comparing multiple interventions simultaneously by combining direct and...

Mixed Treatment Comparisons and Network Meta-Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mixed treatment comparison (MTC) models, also known as network meta-analysis, a powerful statistical methodology for comparing multiple interventions simultaneously by combining direct and indirect evidence. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, methodological approaches for implementation, strategies for troubleshooting common issues like heterogeneity and inconsistency, and frameworks for validating and comparing MTC results with direct evidence. The synthesis of current guidance and applications demonstrates how MTC strengthens evidence-based decision-making in healthcare policy and clinical development, particularly when head-to-head trial data are unavailable.

What Are Mixed Treatment Comparisons? Building the Foundational Knowledge

Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC) and Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) are advanced statistical methodologies that enable the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions, even when direct head-to-head evidence is absent. Within evidence-based medicine, these approaches provide a unified, coherent framework for evaluating the relative efficacy and safety of three or more treatments, addressing a critical need for health technology assessment (HTA) and clinical decision-making [1] [2]. The terminology "Mixed Treatment Comparison" and "Network Meta-Analysis" is often used interchangeably in the scientific literature, though NMA has gained broader usage in recent years [3] [4]. These methods synthesize all available direct and indirect evidence into an internally consistent set of estimates, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional pairwise meta-analyses, which are restricted to comparing only two interventions at a time [1] [5]. This technical guide delineates the core concepts, assumptions, methodologies, and applications of MTC/NMA, framed within the broader context of comparative effectiveness research.

Core Definitions and Relationship

Foundational Terminology

- Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC): A statistical analysis that combines direct evidence from head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with indirect evidence to compare multiple interventions in a single model [1] [2]. The term emphasizes the "mixing" of different types of comparative evidence.

- Network Meta-Analysis (NMA): A methodology for the simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments that forms a connected network of interventions [6] [5]. The term highlights the "network" structure of the evidence, where treatments are nodes and comparisons are edges.

- Indirect Treatment Comparison (ITC): A broader term encompassing any method that compares treatments indirectly via a common comparator, with MTC/NMA being a specific, sophisticated form of ITC [3].

Conceptual Relationship

Although the terms MTC and NMA originated from different statistical traditions, they are functionally equivalent in their modern application [2] [4]. Both methods synthesize evidence from a network of trials to estimate all pairwise relative effects between interventions. The term NMA is increasingly prevalent in contemporary literature, as evidenced by its coverage in 79.5% of articles describing ITC techniques, compared to other methodologies [3]. These methods answer the pivotal question for healthcare decision-makers: "Which treatment should be used for this condition?" when faced with multiple alternatives [2].

Table 1: Prototypical Situations for MTC and NMA Application

| Analysis Type | Included Studies | Rationale or Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Meta-analysis | Study 1: Treatment A vs placebo, n=300Study 2: Treatment A vs placebo, n=150Study 3: Treatment A vs placebo, n=500 | Obtain a more precise estimate of effect size of Treatment A vs placebo; increase statistical power [1] |

| Mixed Treatment Comparison/Network Meta-Analysis | Study 1: Treatment A vs placebo, n=150Study 2: Treatment B vs placebo, n=150Study 3: Treatment B vs Treatment C, n=150 | Estimate effect sizes between A vs B, A vs C, and C vs placebo where no direct comparisons exist [1] |

Key Assumptions and Statistical Foundations

The validity of MTC/NMA depends on three fundamental statistical assumptions, which ensure that the combined direct and indirect evidence provides unbiased estimates of relative treatment effects [1] [5] [4].

Similarity

This assumption requires that the trials included for different pairwise comparisons are sufficiently similar in their methodological characteristics, including study population, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design [1] [5]. Effect modifiers—variables that influence the treatment effect size—must be balanced across treatment comparisons. For example, in an NMA comparing antidepressants, effect modifiers could include inpatient versus outpatient setting, flexibility of medication dosing, and patient comorbidities [4].

Transitivity

Transitivity extends the similarity assumption across the entire treatment network. It necessitates that the distribution of effect modifiers is similar across the different direct comparisons forming the network [5]. In a network comparing A vs B, A vs C, and B vs C, the patients receiving A in the A vs B trials should be comparable to those receiving A in the A vs C trials in terms of key effect modifiers. Violation of transitivity can lead to biased indirect estimates.

Consistency (Coherence)

Consistency refers to the statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison [2] [4]. When both direct and indirect evidence exist for a specific pairwise comparison (e.g., A vs B), the estimates derived from each source should be statistically compatible. Significant disagreement, termed "incoherence" or "inconsistency," suggests violation of the similarity or transitivity assumptions or methodological differences between trials [4].

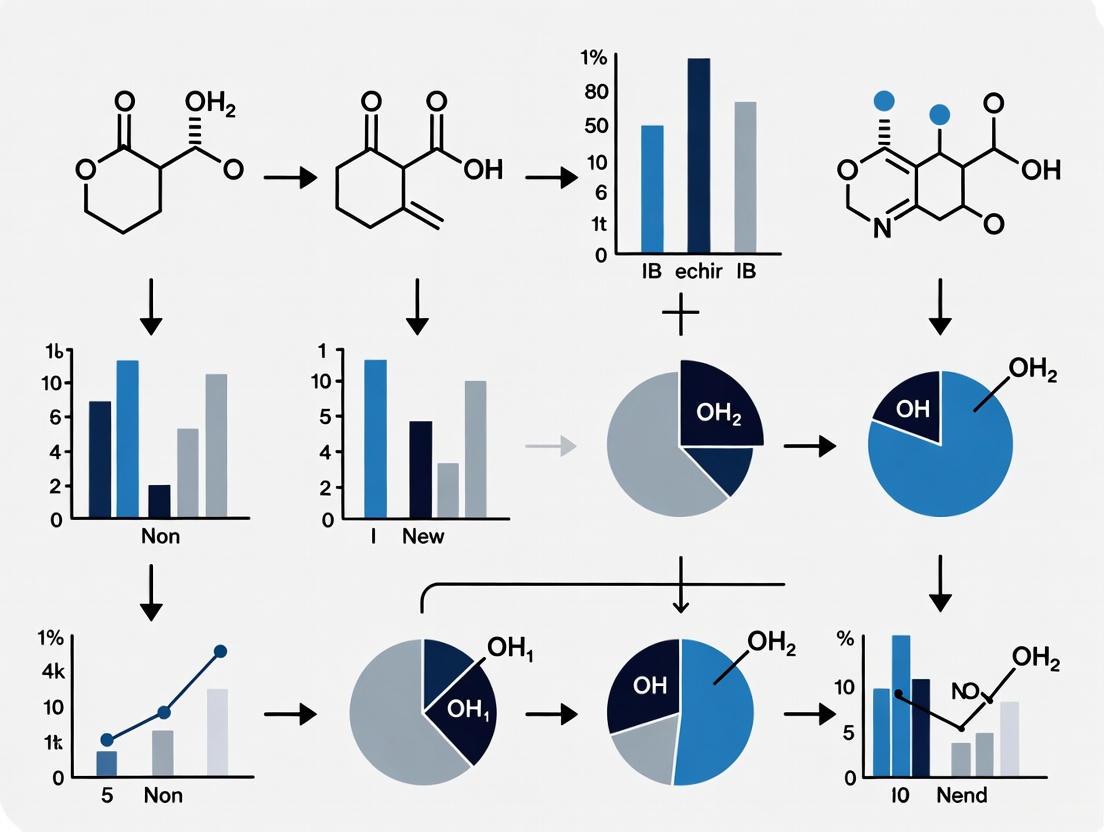

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between these core assumptions and the resulting evidence in a network meta-analysis.

Methodological Workflow and Protocol

Executing a robust MTC/NMA requires a rigorous, pre-specified methodology analogous to conducting a high-quality clinical trial [1]. The process follows established guidelines for systematic reviews, such as those from the Cochrane Collaboration and the PRISMA extension for NMA [1] [5].

Systematic Literature Review and Study Selection

The foundation of any MTC/NMA is a comprehensive systematic literature review designed with pre-specified eligibility criteria (PICO framework: Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) [3]. The search strategy must be documented thoroughly to ensure reproducibility and minimize selection bias. The study selection process is typically visualized using a PRISMA flow diagram [1].

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction from included studies must be performed in a blinded and pre-specified manner [1]. Key extracted information includes study characteristics, patient demographics, intervention details, outcomes, and effect modifiers. The quality of individual RCTs should be assessed using validated tools (e.g., the Jadad scale or Cochrane Risk of Bias tool) [1] [4].

Network Geometry and Evidence Structure

The collection of included studies and their comparisons forms the network geometry [5]. This is visually represented by a network plot where:

- Nodes: Represent the interventions or treatments being compared.

- Edges: Represent the direct head-to-head comparisons between interventions.

- The size of nodes is often proportional to the number of participants receiving that intervention.

- The thickness of edges is often proportional to the number of trials making that direct comparison [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Data Extraction Template for Included Studies

| Study ID | Treatment Arms | Sample Size (n) | Baseline Characteristics (e.g., Mean Age, % Male) | Outcome Data (e.g., Events, Mean, SD) | Effect Modifiers (e.g., Disease Severity, Prior Treatment) | Quality Score (e.g., Jadad) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al. 2020 | A, B | 150 | Age: 45y, 60% Male | Resp A: 45/75, Resp B: 30/75 | High-risk: 40% | 4/5 |

| Jones et al. 2021 | A, C | 200 | Age: 50y, 55% Male | Resp A: 60/100, Resp C: 40/100 | High-risk: 50% | 3/5 |

| Chen et al. 2022 | B, C | 180 | Age: 48y, 58% Male | Resp B: 50/90, Resp C: 45/90 | High-risk: 45% | 5/5 |

Statistical Analysis and Model Implementation

The statistical synthesis involves several key steps:

- Choice of Model: Analysts must choose between a fixed-effects model (assumes a single true treatment effect across all studies) and a random-effects model (allows for heterogeneity in treatment effects across studies) [1] [4]. Random-effects models are often preferred to account for between-study variation.

- Effect Measure Selection: The choice of effect measure (e.g., Odds Ratio [OR], Risk Ratio [RR] for dichotomous outcomes; Mean Difference [MD], Standardized Mean Difference [SMD] for continuous outcomes) depends on the outcome type and must be pre-specified [5].

- Estimation Framework: Analysis can be conducted within a frequentist or Bayesian framework. Bayesian methods, using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation, have been widely adopted for MTC/NMA as they facilitate probabilistic statements about treatment rankings [4].

- Assessment of Heterogeneity and Inconsistency: Statistical tests (e.g., I² for heterogeneity) and specific methods (e.g., side-splitting for inconsistency) are used to evaluate the validity of the model's assumptions [1] [2] [4].

The following flowchart outlines the core experimental protocol for conducting an MTC/NMA.

Analytical Outputs and Interpretation

The results of an MTC/NMA provide a comprehensive summary of the relative effectiveness of all treatments in the network.

League Table

A league table presents all pairwise comparisons in a matrix format, providing the effect estimate and its confidence or credible interval for each treatment comparison [5]. This allows for a direct assessment of which treatments are statistically significantly different from one another.

Table 3: Hypothetical League Table for Sleep Interventions (Outcome: Standardized Mean Difference)*

| Intervention | A (Aromatherapy) | B (Earplugs) | C (Eye Mask) | D (Virtual Reality) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (Earplugs) | -0.61 (-1.18, -0.04) | |||

| C (Eye Mask) | -0.18 (-0.48, 0.13) | 0.44 (-0.05, 0.92) | ||

| D (Virtual Reality) | -0.84 (-1.10, -0.58) | -0.23 (-0.75, 0.29) | -0.66 (-1.01, -0.31) | |

| E (Music) | -0.72 (-1.05, -0.39) | -0.11 (-0.67, 0.45) | -0.54 (-0.85, -0.23) | 0.12 (-0.21, 0.45) |

Note: Data from a hypothetical NMA [5]. Cell entry is the SMD (95% CI) of the row-defining treatment compared to the column-defining treatment. SMD < 0 favors the row treatment.

Treatment Ranking

MTC/NMA models, particularly Bayesian ones, can estimate the probability of each treatment being the best, second best, etc., based on the selected outcome [2] [4]. These rankings are often presented as rankograms or cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA).

Applications and Feasibility Assessment in Drug Development

MTC/NMA has become a cornerstone of comparative effectiveness research, directly informing healthcare policy and clinical practice.

Primary Applications

- Health Economic Evaluations and HTA: MTC/NMA is frequently used to support submissions to HTA bodies, such as the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), by providing comparative efficacy evidence for reimbursement decisions [1] [4].

- Informing Clinical Practice Guidelines: By synthesizing all available evidence, NMA can identify the most effective interventions for inclusion in clinical guidelines, helping to answer "which treatment is best?" [5] [2].

- Evidence Gap Identification: The network structure can reveal where direct comparisons are missing, potentially guiding the design of future clinical trials [2].

Feasibility and Challenges

A critical preliminary step is assessing the feasibility of conducting a valid MTC/NMA. Key considerations include:

- Network Connectivity: A valid NMA requires a connected network where there is a path of comparisons between all treatments [7].

- Clinical and Methodological Heterogeneity: Significant differences in trial populations, interventions, definitions of outcomes, or standard of care can violate the key assumptions and render an NMA unfeasible or invalid [7] [4]. For example, an NMA in polycythemia vera was deemed unfeasible due to heterogeneity in patient populations (newly diagnosed vs. hydroxyurea-resistant), variable definitions of "standard of care," and inconsistent endpoint definitions [7].

- Publication Bias: The tendency for positive results to be published more often than negative ones can lead to biased summary effects in any meta-analysis, including NMA [1].

Table 4: Indirect Treatment Comparison Techniques: Strengths and Limitations

| ITC Technique | Description | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) | Simultaneously compares multiple treatments in a connected network [3]. | Synthesizes all available evidence; provides internally consistent estimates for all comparisons; can rank treatments [1] [2]. | Requires strict similarity, transitivity, and consistency assumptions; complex to implement and interpret [4]. |

| Bucher Method | Simple indirect comparison between two treatments via a common comparator [3]. | Simple and intuitive; no specialized software needed [3]. | Limited to three treatments/two trials; does not incorporate heterogeneity; cannot integrate direct and indirect evidence [3]. |

| Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison (MAIC) | Population-adjusted method that re-weights individual patient data (IPD) from one trial to match the aggregate baseline characteristics of another [3]. | Useful when IPD is available for only one trial; can adjust for cross-trial imbalances in effect modifiers [3]. | Relies on the availability of IPD for at least one trial; limited to comparing two treatments; depends on chosen effect modifiers [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

While MTC/NMA is a statistical methodology, its execution relies on several essential tools and resources. The following table details key components of the analytical toolkit.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MTC/NMA

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in MTC/NMA |

|---|---|---|

| PRISMA-NMA Guidelines | A reporting checklist ensuring transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews incorporating NMA [1] [5]. | Guides the entire process from protocol to reporting, ensuring methodological rigor and reproducibility. |

| Cochrane Handbook | Methodological guidance for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of interventions [5]. | Provides the foundational standards for study identification, quality assessment, and data synthesis. |

| Bayesian Statistical Software (e.g., WinBUGS, OpenBUGS, JAGS) | Specialized software that uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation for fitting complex statistical models [4]. | The primary computational environment for implementing Bayesian NMA models, enabling probabilistic treatment ranking. |

| R packages (e.g., *netmeta, gemtc)* | Statistical packages within the R programming environment for conducting meta-analysis and NMA [3]. | Provide both frequentist and Bayesian frameworks for NMA, facilitating model implementation, inconsistency checks, and visualization. |

| GRADE for NMA | A framework for rating the quality (certainty) of a body of evidence in systematic reviews [5]. | Used to assess the certainty of evidence for each pairwise comparison derived from the NMA, informing clinical recommendations. |

| Sarmentocymarin | Sarmentocymarin|Cardiac Glycoside|For Research Use | Sarmentocymarin is a crystalline steroid cardiac glycoside for research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

| Bruceantinol | Bruceantinol, CAS:53729-52-5, MF:C30H38O13, MW:606.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The exponential growth of medical evidence has necessitated the development of sophisticated statistical methods to synthesize research findings comprehensively. Evidence synthesis has evolved substantially from traditional pairwise methods to increasingly complex network approaches. This evolution represents a paradigm shift in how researchers compare healthcare interventions, moving from direct head-to-head comparisons toward integrated analyses that can simultaneously evaluate multiple interventions. Network meta-analysis (NMA), also known as mixed treatment comparison, has emerged as a critical methodology that extends standard pairwise meta-analysis by enabling indirect comparisons and ranking of multiple treatments [8] [9]. This advancement is particularly valuable for healthcare decision-makers who must often choose among numerous competing interventions, many of which have never been directly compared in randomized controlled trials.

The fundamental advantage of NMA lies in its ability to leverage both direct and indirect evidence, creating a connected network of treatment comparisons that provides a more comprehensive basis for decision-making [8]. While standard pairwise meta-analysis synthesizes evidence from trials comparing the same interventions, NMA facilitates comparisons of interventions that have not been studied head-to-head by connecting them through common comparators [9]. This methodological expansion, however, introduces additional complexity and requires careful attention to underlying assumptions that ensure validity. The core assumptions of transitivity and consistency form the foundation of NMA, distinguishing it conceptually and methodologically from traditional pairwise approaches [8] [9].

This technical guide examines the evolution from pairwise to network meta-analysis within the broader context of mixed treatment comparison models research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides an in-depth examination of methodological foundations, key assumptions, implementation protocols, and current challenges in advanced evidence synthesis methodologies.

Methodological Foundations

Pairwise Meta-Analysis: The Traditional Paradigm

Traditional pairwise meta-analysis represents the foundational approach to evidence synthesis, statistically combining results from multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigate the same intervention comparison [8]. This methodology generates a pooled estimate of the treatment effect between two interventions (typically designated as intervention versus control) by synthesizing all available direct evidence. The internal validity of each included RCT stems from the random allocation of participants to intervention groups, which balances both known and unknown prognostic factors across comparison arms [8].

Within pairwise meta-analysis, variation in treatment effects can manifest at two distinct levels. Within-study heterogeneity occurs when patient characteristics that modify treatment response (effect modifiers) vary among participants within an individual trial [8]. For example, RCTs evaluating statins might include patients with and without coronary artery history, and these subgroups may respond differently to treatment. Between-study heterogeneity arises from systematic differences in study characteristics or patient populations across different trials investigating the same comparison [8]. This occurs because while randomization protects against bias within trials, patients are not randomized to different trials in a meta-analysis.

Table 1: Types of Variation in Pairwise Meta-Analysis

| Type of Variation | Description | Source | Statistical Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-study heterogeneity | Variation in true treatment effects among participants within a trial | Differences in effect modifiers among participants within a trial | Not typically observable with aggregate data |

| Between-study heterogeneity | Systematic differences in treatment effects across trials | Imbalance in effect modifiers across different studies | Measurable via I², Q, or τ² statistics |

When combining studies in pairwise meta-analysis, the presence of between-study heterogeneity does not inherently introduce bias but may render pooled estimates less meaningful if the variation is substantial [8]. In such cases, analysts may pursue alternative strategies such as subgroup analysis or random-effects models that account for this heterogeneity in the precision of estimates.

Network Meta-Analysis: An Integrated Framework

Network meta-analysis extends pairwise methodology by simultaneously synthesizing evidence from a network of RCTs comparing multiple interventions [8] [9]. Whereas standard meta-analysis examines one comparison at a time, NMA integrates all direct and indirect evidence into a unified analysis, enabling comparisons among all interventions in the network. This approach effectively broadens the evidence base considered for each treatment effect estimate [8].

The conceptual foundation of NMA rests on indirect comparisons, which can be illustrated through a simple example. Consider trial 1 comparing treatments B versus A (yielding effect estimate d̂_AB), and trial 2 comparing treatments C versus B (yielding effect estimate d̂_CB). An indirect estimate for the comparison C versus A can be derived as d̂_CA = d̂_CB + d̂_AB [9]. This indirect comparison maintains the benefits of randomization within each trial while allowing for differences across trials, provided these differences affect only prognosis and not treatment response [9].

In NMA, three types of treatment effect variation can occur: (1) true within-study variation (only observable with individual patient data), (2) true between-study variation for a particular treatment comparison (heterogeneity), and (3) true between-comparison variation in treatment effects [8]. This additional source of variability distinguishes NMA from standard pairwise meta-analysis and introduces the critical concepts of transitivity and consistency.

Table 2: Evolution from Pairwise to Network Meta-Analysis

| Feature | Pairwise Meta-Analysis | Network Meta-Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Comparisons | Direct evidence only | Direct, indirect, and mixed evidence |

| Interventions | Typically two (e.g., intervention vs. control) | Multiple interventions simultaneously |

| Evidence Use | Synthesizes studies of identical comparisons | Synthesizes studies of different but connected comparisons |

| Output | Single pooled effect estimate | Multiple effect estimates with ranking possibilities |

| Key Assumptions | Homogeneity (or explainable heterogeneity) | Transitivity and consistency |

| Complexity | Relatively straightforward | Increased complexity in modeling and interpretation |

Critical Assumptions and Evaluation Methods

Transitivity: The Conceptual Foundation

The assumption of transitivity constitutes the conceptual foundation underlying the validity of network meta-analysis. Transitivity requires that the distribution of effect modifiers—study or patient characteristics associated with the magnitude of treatment effect—is similar across the different types of direct comparisons in the network [8]. In practical terms, this means that the participants in studies of different comparisons (e.g., AB studies versus AC studies) are sufficiently similar that their results can be meaningfully combined [8].

The relationship between effect modifiers and transitivity can be illustrated through specific scenarios. When the distribution of effect modifiers is balanced across different direct comparisons (e.g., AB and AC studies), the indirect comparison provides an unbiased estimate [8]. However, when an imbalance exists in the distribution of effect modifiers between different types of direct comparisons, the related indirect comparisons will be biased [8]. For example, if AB studies predominantly include patients with severe disease while AC studies include mostly mild cases, and disease severity modifies treatment response, then the indirect BC comparison would be confounded by this imbalance [8].

The following diagram illustrates the flow of evidence and key assumptions in network meta-analysis:

Network Meta-Analysis Evidence Flow and Key Assumptions

Consistency: The Statistical Manifestation

Consistency represents the statistical manifestation of the transitivity assumption, referring to the agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison [9]. In a consistent network, the direct estimate of a treatment effect (e.g., from head-to-head studies comparing B and C) agrees with the indirect estimate (e.g., obtained via a common comparator A) within the bounds of random error [9]. The consistency assumption can be expressed mathematically for a simple ABC network as: δ_AC = δ_AB + δ_BC, where δ represents the true underlying treatment effect for each comparison [9].

When consistency is violated, this is referred to as inconsistency or incoherence, which occurs when different sources of evidence (direct and indirect) for the same comparison yield conflicting results [9]. Inconsistency can arise from several sources, including differences in participant characteristics across comparisons, different versions of treatments in different comparisons, or methodological differences between studies of different comparisons [9].

Two specific types of inconsistency have been described in the literature. Loop inconsistency refers to disagreement between different sources of evidence within a closed loop of treatments (typically a three-treatment loop) [9]. Design inconsistency occurs when the effect of a specific contrast differs depending on the design of the study (e.g., whether the estimate comes from a two-arm trial or a multi-arm trial that includes additional treatments) [9]. The presence of multi-arm trials in evidence networks complicates the definition and detection of loop inconsistency [9].

Methods for Evaluating Inconsistency

Several statistical approaches have been developed to evaluate inconsistency in network meta-analyses. The design-by-treatment interaction model provides a general framework for investigating inconsistency that successfully addresses complications arising from multi-arm trials [9]. This approach treats inconsistency as an interaction between the treatment contrast and the design (set of treatments compared in a study) [9].

The node-splitting method is another popular approach that directly compares direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons [10]. This method "splits" the evidence for a particular comparison into direct and indirect components and assesses whether they differ significantly [10]. Different parameterizations of node-splitting models make different assumptions: symmetrical methods assume both treatments in a contrast contribute to inconsistency, while asymmetric methods assume only one treatment contributes [10].

Novel graphical tools have also been developed to locate inconsistency in network meta-analyses. The net heat plot visualizes which direct comparisons drive each network estimate and displays hot spots of inconsistency, helping researchers identify which suspicious direct comparisons might explain the presence of inconsistency [11]. This approach combines information about the contribution of each direct estimate to network estimates with heat colors corresponding to changes in agreement between direct and indirect evidence when relaxing consistency assumptions for specific comparisons [11].

Implementation and Analytical Protocols

Network Meta-Analysis Workflow

Implementing a valid network meta-analysis requires meticulous attention to each step of the analytical process. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages in conducting an NMA, from network specification to interpretation of results:

Network Meta-Analysis Implementation Workflow

Statistical Models for Network Meta-Analysis

The statistical foundation of NMA can be implemented through both frequentist and Bayesian frameworks. The general linear model for network meta-analysis with fixed effects can be expressed in matrix notation as: Y = Xθ_net + ε, where Y is a vector of observed treatment effects from all studies, X is the design matrix capturing the network structure at the study level, θ_net represents the parameters of the network meta-analysis, and ε represents the error term [11].

For fixed-effects models, it is assumed that all studies estimating the same comparison share a common treatment effect, with any observed differences attributable solely to random sampling variation. Random-effects models, in contrast, allow for heterogeneity by assuming that the underlying treatment effects for the same comparison follow a distribution, typically normal: θ_i ~ N(δ_JK, τ²) for pairwise comparison JK [9]. The random-effects approach is generally more conservative and appropriate when between-study heterogeneity is present.

The consistency assumption can be incorporated into the model through linear constraints on the basic parameters. For example, in a network with treatments A, B, and C, the consistency assumption implies that δ_AC = δ_AB + δ_BC [9]. Inconsistency can be assessed by comparing models with and without these consistency constraints, using measures such as the deviance information criterion (DIC) in Bayesian analysis or likelihood ratio tests in frequentist analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions for Network Meta-Analysis

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Network Meta-Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Software | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (gemtc, netmeta, pcnetmeta packages) | Implement statistical models for NMA | Bayesian and frequentist approaches, inconsistency detection, network graphics |

| Stata (network, mvmeta packages) | Perform NMA in Stata environment | Suite of commands for network meta-analysis | |

| WinBUGS/OpenBUGS/JAGS | Bayesian analysis using MCMC sampling | Flexibility for complex models, random-effects, consistency/inconsistency models | |

| Inconsistency Detection | Node-splitting methods | Evaluate disagreement between direct and indirect evidence | Specific comparison assessment, various parameterizations available |

| Design-by-treatment interaction model | Global test of inconsistency | Handles multi-arm trials appropriately, comprehensive inconsistency assessment | |

| Net heat plot | Graphical inconsistency assessment | Visualizes drivers and hot spots of inconsistency | |

| Visualization | Network diagrams | Illustrate evidence structure | Node size (sample size), edge thickness (number of studies) |

| Contribution matrices | Show contribution of direct estimates to network results | Informs about evidence flow and precision sources | |

| Ranking plots | Display treatment hierarchies | Rankograms, cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA) |

Current Challenges and Methodological Frontiers

Methodological Challenges in Evolving Evidence Networks

Network meta-analysis faces several ongoing methodological challenges, particularly in the context of evolving evidence networks. Living systematic reviews (LSRs) and updated systematic reviews (USRs) represent frameworks for keeping syntheses current with rapidly expanding literature, but they introduce complexities for NMA [12]. Repeatedly updating an NMA can inflate type I error rates due to multiple testing, and heterogeneity estimates may fluctuate with each update, potentially affecting effect estimates and clinical interpretations [12].

In NMA updates, the transitivity assumption must be reassessed each time new studies are added, as introducing new interventions or additional evidence for existing comparisons may alter the distribution of effect modifiers across the network [12]. Similarly, consistency assessment becomes more complex in living reviews, as statistical tests for inconsistency may have insufficient power at early updates when few studies are available [12]. The introduction of new interventions can change the network geometry, potentially creating new loops where inconsistency might occur.

Trial sequential analysis (TSA) has been proposed as one method to address error inflation in updated meta-analyses by adapting sequential clinical trial methodology to evidence synthesis [12]. TSA establishes a required information size and alpha spending function to determine statistical significance, adjusting for the cumulative nature of evidence updates. However, application of TSA to NMA is complex, as it must account for both heterogeneity and potential inconsistency in the network [12].

Advanced Methodological Developments

Recent methodological research has addressed several complex scenarios in network meta-analysis. Generalized linear mixed models with node-splitting parameterizations provide flexible frameworks for evaluating inconsistency, particularly for binary and count outcomes [10]. These approaches allow researchers to specify different parameterizations depending on whether they believe one or both treatments in a comparison contribute to inconsistency.

Advanced graphical tools continue to be developed to enhance the visualization and interpretation of network meta-analyses. The net heat plot, for example, combines information about the contribution of direct estimates to network results with measures of inconsistency to identify potential drivers of disagreement in the network [11]. This matrix-based visualization helps researchers identify which direct comparisons are contributing to inconsistency and which network estimates are affected.

Methodological research has also addressed the challenge of multi-arm trials in network meta-analysis, which complicate the definition and detection of inconsistency because loop inconsistency cannot occur within a multi-arm trial [9]. The design-by-treatment interaction model has emerged as a comprehensive approach to evaluate inconsistency in networks containing multi-arm trials, as it successfully addresses the complications that arise from such studies [9].

The evolution from pairwise to network meta-analysis represents significant methodological progress in evidence synthesis, enabling comprehensive comparison of multiple interventions through integrated analysis of direct and indirect evidence. This advancement has dramatically enhanced the utility of systematic reviews for clinical and policy decision-making by providing comparative effectiveness estimates for all relevant interventions, even in the absence of head-to-head studies.

The validity of network meta-analysis depends critically on the transitivity assumption, which requires balanced distribution of effect modifiers across different treatment comparisons, and its statistical manifestation, consistency, which denotes agreement between direct and indirect evidence. Various statistical methods, including node-splitting and design-by-treatment interaction models, along with graphical tools like net heat plots, have been developed to evaluate these assumptions and identify potential inconsistency in evidence networks.

As evidence synthesis methodologies continue to evolve, network meta-analysis faces new challenges in the context of living systematic reviews and rapidly expanding evidence bases. Ongoing methodological research addresses these challenges through developing sequential methods, advanced inconsistency detection techniques, and enhanced visualization tools. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding both the capabilities and assumptions of network meta-analysis is essential for appropriate application and interpretation of this powerful evidence synthesis methodology.

Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC) models, also known as Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), represent an advanced statistical methodology that synthesizes evidence from both direct head-to-head comparisons and indirect comparisons across multiple interventions [13] [14]. These models enable clinicians and policymakers to compare the relative effectiveness of multiple treatments, even when direct comparative evidence is absent, by leveraging a network of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) connected through common comparators [15] [16]. The validity and reliability of conclusions drawn from an MTC are contingent upon fulfilling three fundamental assumptions: homogeneity, similarity (transitivity), and consistency [17] [18]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core assumptions, detailing their conceptual foundations, assessment methodologies, and implications for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in evidence synthesis.

Conceptual Foundations of MTC Core Assumptions

Homogeneity

Homogeneity refers to the degree of variability in the relative treatment effects within the same pairwise comparison across different studies [17] [18]. In a homogeneous set of studies, any observed differences in treatment effect estimates are attributable solely to random chance (sampling error) rather than to systematic differences in study design or patient populations. This concept is specific to each direct head-to-head comparison within the broader network. Violations of homogeneity, termed heterogeneity, indicate that the studies included for a particular treatment pair are not estimating a common effect size, potentially compromising the validity of pooling their results.

Similarity (Transitivity)

The similarity assumption, also referred to as transitivity, concerns the validity of combining direct and indirect evidence across the entire network [17] [18]. It posits that the included trials are sufficiently similar in all key design and patient characteristics that are potential effect modifiers [17]. In practical terms, this means that if we were to imagine all trials as part of one large multi-arm trial, the distribution of effect modifiers would be similar across the different treatment comparison groups. The transitivity assumption underpins the legitimacy of making indirect comparisons; if studies comparing Treatment A vs. Treatment C differ systematically from studies comparing Treatment B vs. Treatment C, then an indirect comparison of A vs. B via C may be biased.

Consistency

Consistency is the statistical manifestation of the similarity assumption, describing the agreement between direct evidence (from studies that directly compare two treatments) and indirect evidence (estimated through a common comparator) for the same treatment comparison [13] [17] [18]. When both direct and indirect evidence exist for a treatment pair within a network, their effect estimates should be coherent, within the bounds of random error. Inconsistency arises when these estimates disagree significantly, suggesting a violation of the underlying similarity assumption or the presence of other biases within the network structure.

Table 1: Overview of Core Assumptions in Mixed Treatment Comparisons

| Assumption | Conceptual Definition | Scope of Application | Primary Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homogeneity | Variability of treatment effects within the same pairwise comparison [18]. | Individual pairwise comparisons (e.g., all A vs. B studies) [17]. | Heterogeneity within a single treatment contrast. |

| Similarity/Transitivity | Similarity of trials across different comparisons with respect to effect modifiers [17] [18]. | The entire network of trials and comparisons. | Systematic differences in study or patient characteristics across different comparisons. |

| Consistency | Agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison [13] [18]. | Treatment comparisons where both direct and indirect evidence exist. | Discrepancy between different sources of evidence for the same contrast. |

Methodological Assessment and Evaluation

Assessing Homogeneity

The assessment of homogeneity is a two-stage process involving both qualitative and quantitative evaluations.

Qualitative Assessment: Researchers should systematically tabulate and compare the clinical and methodological characteristics of all studies within each pairwise comparison. Key characteristics to examine include patient demographics (e.g., age, disease severity, comorbidities), intervention details (e.g., dosage, formulation), study design (e.g., duration, outcome definitions, risk of bias), and context (e.g., setting, concomitant treatments) [17] [18]. This qualitative review helps identify potential effect modifiers that may explain observed statistical heterogeneity.

Quantitative Assessment: Statistical heterogeneity within each pairwise comparison can be quantified using measures such as the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance [17] [18]. An I² value greater than 50% is often considered to represent substantial heterogeneity [18]. The between-study variance (τ²) is another key metric, estimated within a random-effects model framework.

Table 2: Methods for Assessing the Core Assumptions of MTC

| Assumption | Qualitative/Scientific Assessment Methods | Quantitative/Statistical Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Homogeneity | Comparison of Clinical/Methodological Characteristics (PICO elements) [18]. | I² statistic, Cochran's Q test, estimation of τ² (between-study variance) [17] [18]. |

| Similarity/Transitivity | Systematic evaluation of the distribution of effect modifiers across the different treatment comparisons in the network [17] [18]. | Network meta-regression to test for interaction between treatment effect and trial-level covariates [19]. |

| Consistency | Evaluation of whether clinical/methodological differences identified could explain disagreement between direct and indirect evidence [17]. | Global Approaches: Design-by-treatment interaction test [13]. Local Approaches: Node-splitting method [17] [18], Comparison of direct and indirect estimates in a specific loop. |

Evaluating Similarity (Transitivity)

Evaluating the similarity assumption is primarily a qualitative and clinical judgment, as it precedes the statistical analysis [17]. There are no definitive statistical tests for transitivity; its assessment relies on a thorough understanding of the clinical context and the disease area.

- Identifying Effect Modifiers: The first step is to identify variables that are known or suspected to modify the relative treatment effect. These are often prognostic factors or baseline characteristics that influence the outcome and whose effect may differ depending on the treatment [17].

- Comparing Distributions: Once potential effect modifiers are identified, researchers must assess whether their distributions are balanced across the different treatment comparisons. For example, if all studies comparing Treatment B versus Treatment C enrolled a population with high disease severity, while studies comparing Treatment A versus Treatment C enrolled a population with low disease severity, and severity is an effect modifier, the assumption of transitivity for an indirect A vs. B comparison may be violated.

Advanced methods like network meta-regression can be used to explore the impact of trial-level covariates on treatment effects, thereby providing a quantitative check on potential intransitivity [19].

Testing for Consistency

Consistency can be evaluated using both global and local methods.

- Global Methods: Approaches like the design-by-treatment interaction model assess inconsistency across the entire network simultaneously [13]. This method evaluates whether the treatment effect estimates depend on the design of the studies (i.e., the set of treatments being compared).

- Local Methods: The node-splitting method is a popular local approach that separates evidence for a particular treatment comparison into direct and indirect components [17] [18]. It then statistically tests for a difference between these two estimates. This method is particularly useful for pinpointing the specific comparisons in the network where inconsistency exists.

Another practical approach involves using residual deviance and leverage statistics to identify studies that contribute most to the model's poor fit, which may indicate inconsistency. Iteratively removing such studies and recalculating the MTC can help explore the robustness of the results [18].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core assumptions and the process of evaluating consistency within a network.

Logical Flow for Evaluating MTC Assumptions

A Stepwise Workflow for Practical Application

A structured, stepwise approach is recommended to ensure the robustness of an MTC. The following workflow, derived from practical application in health technology assessments, outlines this process [18].

Step 1: Ensuring Clinical Similarity

The initial phase focuses on constructing a clinically sound and similar study pool, which forms the foundation for all subsequent analyses [18].

- Protocol & Eligibility: Define a precise research question using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) framework and establish strict eligibility criteria before commencing the review [13] [18].

- Systematic Review: Conduct a comprehensive systematic literature review to identify all potentially relevant RCTs, minimizing selection bias [13] [17].

- Assess Effect Modifiers: Critically appraise the included studies for known or suspected effect modifiers. Exclude studies that are fundamentally dissimilar in population, intervention, comparator, or outcome definition from the core network of interest [18]. For instance, studies on a specific sub-population (e.g., treatment-resistant patients) might be analyzed separately from studies on the general population if the treatment effect is expected to differ.

Step 2: Evaluating Statistical Homogeneity

After forming a clinically similar pool, the next step is to assess statistical homogeneity within each direct pairwise comparison [18].

- Pairwise Meta-Analysis: Perform standard pairwise meta-analyses (e.g., using random-effects models) for each treatment comparison where multiple direct studies exist.

- Quantify Heterogeneity: Calculate I² statistics and τ² for each comparison.

- Address Heterogeneity: If substantial heterogeneity (e.g., I² > 50%) is detected, investigate potential causes by examining the clinical and methodological characteristics of the contributing studies. If specific factors (e.g., high risk of bias, a particular patient subgroup) are identified as sources of heterogeneity, consider excluding those studies from the main analysis and conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of their exclusion [18].

Step 3: Checking Network Consistency

The final step involves checking the statistical consistency of the entire network [18].

- Global Check: Use a global method, such as the design-by-treatment interaction test, to get an overview of inconsistency in the network.

- Local Check: Employ local methods, like node-splitting, to identify specific comparisons where direct and indirect evidence disagree.

- Residual Deviance: In Bayesian frameworks, use residual deviance and leverage statistics to identify studies that are outliers or contribute significantly to inconsistency [18].

- Manage Inconsistency: If inconsistency is found, explore its sources. This may involve checking for errors in data extraction, re-examining the clinical similarity of studies in inconsistent loops, or using more complex models that account for inconsistency. As a last resort, excluding the handful of studies contributing most to inconsistency and re-running the analysis can provide a view of robust, consistent results [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MTC Research

Table 3: Key Software and Methodological Tools for MTC Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| R (gemtc, netmeta, BUGSnet packages) [13] | Statistical Software | A free software environment for statistical computing and graphics. Specific packages facilitate both frequentist and Bayesian NMA. | Highly flexible and powerful, but requires programming expertise. Active user community. |

| WinBUGS / OpenBUGS [13] [16] | Statistical Software | Specialized software for Bayesian analysis Using Gibbs Sampling. Implements complex hierarchical models like MTC. | Pioneering software for Bayesian MTC. Requires knowledge of the BUGS modeling language. |

| Stata [13] | Statistical Software | A general-purpose statistical software package. Capable of performing frequentist NMA (e.g., with network suite of commands). |

Widely used in medical statistics. Can be more accessible for those familiar with Stata. |

| Node-Splitting Method [17] [18] | Statistical Method | A local approach to evaluate inconsistency by splitting evidence for a specific comparison into direct and indirect components. | Excellent for pin-pointing the location of inconsistency in the network. |

| I² Statistic [17] [18] | Statistical Metric | Quantifies the percentage of total variability in a set of effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. | Standardized and intuitive measure for assessing homogeneity in pairwise meta-analysis. |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [17] | Methodological Tool | A standardized tool for assessing the internal validity (risk of bias) of randomized trials. | Critical for evaluating the quality of the primary studies feeding into the MTC. |

| Cucurbitaxanthin A | Cucurbitaxanthin A, CAS:103955-77-7, MF:C40H56O3, MW:584.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Kushenol L | Kushenol L, CAS:101236-50-4, MF:C25H28O7, MW:440.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The assumptions of homogeneity, similarity, and consistency are not mere statistical formalities but are the foundational pillars that determine the validity of any mixed treatment comparison. Homogeneity ensures that direct evidence is coherently synthesized, similarity justifies the very possibility of making indirect comparisons, and consistency confirms that both types of evidence tell a congruent story. A rigorous MTC requires a proactive, stepwise approach that begins with a clinically informed systematic review, progresses through quantitative checks for heterogeneity and inconsistency, and involves ongoing critical appraisal of the underlying evidence base. As the use of MTCs continues to grow in health technology assessment and drug development [15], a deep and practical understanding of these core assumptions is indispensable for researchers aiming to generate reliable evidence to inform clinical practice and healthcare policy.

Mixed Treatment Comparisons (MTCs), also known as network meta-analyses, represent a sophisticated statistical methodology that enables the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions within a unified analytical framework. This in-depth technical guide examines the core principles, rationales, and methodological considerations for implementing MTCs in comparative effectiveness research. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this whitepaper synthesizes current guidance from leading health technology assessment organizations and regulatory bodies, outlining explicit scenarios where MTCs provide distinct advantages over conventional pairwise meta-analyses. We provide detailed experimental protocols, structured data presentation standards, and visualization tools to support the rigorous application of MTC methodology within the broader context of evidence synthesis and treatment decision-making.

Mixed Treatment Comparisons (MTCs) have emerged as a powerful methodology in evidence-based medicine for comparing multiple treatments simultaneously when head-to-head clinical trial evidence is limited or unavailable. Unlike traditional pairwise meta-analyses that directly compare only two interventions at a time, MTCs incorporate both direct evidence (from studies directly comparing treatments) and indirect evidence (through common comparator interventions) to form a connected network of treatment effects [20]. This approach allows for the estimation of relative treatment effects between all interventions in the network, even for pairs that have never been directly compared in clinical trials.

The fundamental rationale for conducting MTCs stems from the practical realities of clinical research and drug development. Complete sets of direct comparisons between all available treatments for a condition are rarely available, creating significant evidence gaps in traditional systematic reviews. MTC methodology addresses this limitation by enabling researchers to rank treatments according to their effectiveness or safety, inform economic evaluations, and guide clinical decision-making with more complete evidence networks. The value proposition of MTCs is particularly strong in fields with numerous treatment options, such as cardiology, endocrinology, psychiatry, and rheumatology, where they can provide crucial insights for formulary decisions and clinical guideline development [20].

Scopes and Applications of MTCs

Clinical and Policy Decision-Making Contexts

MTCs are particularly valuable in specific clinical and healthcare policy scenarios. According to guidance documents from major health technology assessment organizations, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Cochrane Collaboration, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), MTCs are most beneficial when [20]:

- Multiple treatment options exist without direct comparative evidence for all relevant pairs

- Clinical guidelines require ranking of therapeutic alternatives by efficacy, safety, or cost-effectiveness

- Resource allocation decisions demand comprehensive understanding of relative treatment benefits

- Drug development priorities need establishment based on existing treatment landscape

- Gaps in the evidence base exist where direct trials are ethically or practically challenging to conduct

The application of MTCs extends beyond pharmacologic interventions to include comparisons of behavioral interventions, surgical procedures, medical devices, and diagnostic strategies, making them versatile tools across healthcare research domains [20].

Quantitative Scope Assessment Framework

Table 1: Criteria for Determining When to Conduct an MTC

| Assessment Factor | Favorable Conditions for MTC | Unfavorable Conditions for MTC |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Interventions | ≥3 competing interventions | Only 2 interventions of interest |

| Evidence Connectivity | Connected network through common comparators | Disconnected network without linking interventions |

| Clinical Relevance | Need to rank multiple treatment options | Only single pairwise comparison needed |

| Evidence Gaps | Missing direct comparisons between important interventions | Complete direct evidence available for all comparisons |

| Policy Urgency | Pressing need for comprehensive treatment guidance | Limited decision-making implications |

Methodological Rationale and Theoretical Foundation

Statistical Assumptions and Requirements

The validity of MTC conclusions depends on several critical statistical assumptions that must be evaluated before undertaking an analysis. These foundational assumptions represent the methodological rationales that justify the use of indirect evidence [20]:

- Transitivity Assumption: The distribution of effect modifiers (patient characteristics that influence treatment outcome) should be similar across treatment comparisons in the network. This implies that were a direct comparison available, it would yield similar results to the indirect comparison.

- Consistency Assumption: Direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison should be in statistical agreement. Consistency validates that the different sources of evidence measure the same underlying treatment effect.

- Homogeneity Assumption: Studies included in each direct comparison should be sufficiently similar in their design and patient populations to be appropriately combined.

Violations of these assumptions threaten the validity of MTC results and must be carefully assessed through clinical and statistical methods before proceeding with analysis.

Experimental Design and Protocol Development

A rigorously developed protocol is essential for conducting a valid MTC. The following detailed methodology outlines the key steps in the MTC process [20]:

Phase 1: Network Specification

- Define precisely the clinical question, including patient populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes of interest (PICO framework)

- Establish eligibility criteria for study inclusion with particular attention to potential effect modifiers

- Develop a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases (e.g., MEDLINE, Cochrane Central, EMBASE)

- Document the search strategy explicitly, including dates, databases, and search terms

Phase 2: Data Collection and Management

- Perform dual independent study selection with conflict resolution procedures

- Extract data using standardized forms capturing study characteristics, quality indicators, and outcome data

- Identify and record potential effect modifiers for assessment of transitivity assumption

- Map all available direct comparisons to visualize the evidence network

Phase 3: Statistical Analysis Plan

- Specify Bayesian or Frequentist analytical approach with justification

- Select fixed-effect or random-effects model based on assessment of heterogeneity

- Define prior distributions for Bayesian analyses (if applicable)

- Plan assessment of consistency using appropriate statistical methods (e.g., node-splitting)

- Outline sensitivity analyses to test robustness of findings

Phase 4: Results Interpretation and Reporting

- Apply appropriate methods to rank treatments while acknowledging limitations

- Report findings with measures of uncertainty (e.g., credible intervals or confidence intervals)

- Discuss limitations, including potential violations of assumptions and network weaknesses

- Adhere to reporting guidelines such as PRISMA-NMA

Evidence Network Visualization

MTC Methodology Workflow

Practical Implementation Considerations

Analytical Framework Selection

The choice between Bayesian and Frequentist approaches for MTC implementation represents a critical methodological decision with practical implications for analysis and interpretation. Based on examination of existing MTC applications in systematic reviews, each approach offers distinct advantages [20]:

Table 2: Comparison of Bayesian vs. Frequentist Approaches in MTC

| Characteristic | Bayesian MTC | Frequentist MTC |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence in Literature | More commonly used (≈80% of published MTCs) | Less frequently implemented (≈20% of published MTCs) |

| Model Parameters | Requires specification of prior distributions | Relies on likelihood-based estimation |

| Results Interpretation | Direct probability statements (e.g., probability Treatment A is best) | Confidence intervals and p-values |

| Computational Requirements | Often more intensive, typically using WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | Generally less intensive, using Stata/SAS/R |

| Handling of Complex Models | More flexible for sophisticated model structures | Can be limited for highly complex networks |

| Treatment Ranking | Natural framework for ranking probabilities | Requires additional methods for ranking |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of MTC requires both methodological expertise and appropriate analytical tools. The following table details key resources in the MTC researcher's toolkit [20]:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for MTC Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | WinBUGS, OpenBUGS, R, SAS, Stata | Bayesian and Frequentist model estimation and analysis |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Cochrane Risk of Bias, GRADE for NMA | Evaluate study quality and rate confidence in effect estimates |

| Data Extraction Platforms | Covidence, DistillerSR, Excel templates | Systematic data collection and management |

| Network Visualization | R (netmeta, gemtc packages), Stata network maps | Create evidence network diagrams and results presentations |

| Consistency Assessment | Node-splitting, design-by-treatment interaction models | Evaluate statistical consistency between direct and indirect evidence |

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA-NMA checklist | Ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting of methods and findings |

Signaling Pathways in MTC Methodology

The methodological foundation of MTCs can be conceptualized as a series of interconnected signaling pathways where evidence flows through the network to inform treatment effects. Understanding these pathways is essential for appropriate implementation and interpretation.

MTC Evidence Flow Network

Mixed Treatment Comparisons represent a methodologically sophisticated approach to evidence synthesis that expands the utility of conventional systematic reviews. The decision to conduct an MTC should be guided by the presence of multiple interventions with incomplete direct comparison evidence, the connectivity of the evidence network, and the need for comprehensive treatment rankings to inform clinical or policy decisions. Successful implementation requires rigorous assessment of key assumptions (transitivity, consistency, homogeneity), appropriate selection of analytical framework (Bayesian or Frequentist), and adherence to established methodological standards. When properly conducted and reported, MTCs provide valuable evidence for comparative effectiveness research, drug development decisions, and clinical guideline development, filling critical gaps where direct evidence is absent or insufficient. The ongoing development of MTC methodology, including more sophisticated approaches to assessing assumption violations and handling complex evidence structures, continues to enhance its value for evidence-based decision-making across healthcare domains.

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), also known as Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC), is a sophisticated statistical methodology that extends traditional pairwise meta-analysis by simultaneously synthesizing evidence from a network of interventions [21] [22]. Its core advantage lies in the ability to compare multiple treatments, even those never directly compared in head-to-head trials, by utilizing both direct evidence (from studies comparing treatments directly) and indirect evidence (inferred through a common comparator) [23] [22]. The architecture of this evidence—how the various treatments (nodes) and existing comparisons (edges) interconnect—is termed network geometry. The geometry of a network is not merely a visual aid; it is fundamental to understanding the scope, reliability, and potential biases of an NMA [22]. A well-connected and thoughtfully analyzed network geometry allows for robust ranking of treatments and informs clinical and policy decisions, forming a critical component of modern evidence-based medicine [21].

Core Concepts and Key Assumptions

Before delving into specific geometries, it is essential to grasp the foundational concepts and assumptions that underpin a valid NMA.

- Transitivity: This is the fundamental assumption that makes indirect comparisons plausible. It requires that the effect modifiers—clinical or methodological characteristics that can influence the outcome (e.g., disease severity, patient age, trial duration)—are sufficiently similar across all studies included in the network [21] [23]. For instance, if all trials comparing A vs. B and B vs. C are in a severely ill population, but the trials for A vs. C are in a mildly ill population, the transitivity assumption is violated. Transitivity is a clinical and methodological assumption that cannot be proven statistically but must be critically assessed by experts before conducting an NMA [21].

- Consistency: This is an extension of transitivity into the statistical domain. Consistency refers to the statistical agreement between direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (inferred through the network) for the same treatment comparison [23] [22]. When both direct and indirect evidence exist for a comparison, forming a "closed loop," statistical tests can be applied to assess inconsistency. The presence of significant inconsistency suggests a violation of the transitivity assumption or other biases and must be investigated [21].

Table 1: Glossary of Essential Network Meta-Analysis Terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Node | Represents an intervention or technology under evaluation in the network [22]. |

| Edge | The line connecting two nodes, representing the availability of direct evidence from one or more studies [22]. |

| Common Comparator | An intervention (e.g., 'B') that serves as an anchor, allowing for indirect comparison between other interventions (e.g., A and C) [22]. |

| Direct Treatment Comparison | A comparison of two interventions based solely on studies that directly compare them (head-to-head trials) [22]. |

| Indirect Treatment Comparison | An estimate of the relative effect of two interventions that leverages their direct comparisons with a common comparator [22]. |

| Network Geometry | The overall pattern or structure formed by the nodes and edges in a network, describing how evidence is interconnected [22]. |

| Closed Loop | A part of the network where interventions are directly connected, forming a closed geometry (e.g., a triangle), allowing for both direct and indirect evidence to inform the comparisons [22]. |

Types of Network Geometry and Their Interpretation

Network geometries can range from simple to highly complex. Each structure presents unique advantages and methodological challenges.

Star Geometry

A star geometry is one of the simplest network forms, characterized by a single, central common comparator connected to all other interventions in the network. There are no direct connections between the peripheral interventions.

Star network with a common comparator

- Interpretation and Implications: In a star network, all comparisons between peripheral interventions (e.g., Drug A vs. Drug B) are purely indirect. The validity of these comparisons rests entirely on the transitivity assumption [21] [22]. If the trials connecting each drug to the common comparator are sufficiently similar in their effect modifiers, the indirect estimates can be valid. However, this geometry offers no means to statistically check for consistency, as there are no closed loops. It is a fragile structure highly dependent on the quality and homogeneity of the included studies.

Loop Geometry

A loop geometry emerges when three or more interventions are directly connected, forming a closed structure. The simplest loop is a triangle.

A closed-loop network enabling consistency checks

- Interpretation and Implications: The presence of a closed loop is methodologically significant. It means that for at least one comparison (e.g., A vs. C), both direct evidence (from A-C trials) and indirect evidence (via A-B-C) are available [22]. This allows for a statistical assessment of consistency between the direct and indirect estimates [21] [23]. Detected inconsistency signals potential problems with transitivity or other biases and requires investigation. Loops therefore strengthen a network by providing a built-in mechanism for verifying the coherence of the evidence.

Complex and Asymmetrical Structures

Most real-world NMAs exhibit complex geometries that combine multiple loops, side-arms, and potentially asymmetrical evidence distribution.

A complex network with varied evidence

- Interpretation and Implications:

- Asymmetry: The thickness of edges and size of nodes often carry meaning, representing the number of trials or participants for a given comparison or intervention [21] [23]. In the diagram above, thicker lines indicate more trials, and larger nodes indicate more participants. This asymmetry highlights which parts of the network are supported by more robust evidence. Comparisons relying on thin edges or long, indirect pathways may yield less precise and potentially less reliable estimates.

- Robustness: Networks with more connections and multiple paths for indirect comparisons are generally more robust. They "borrow strength" across the entire network, improving the precision of effect estimates [21]. The geometry can also inform the design of future trials by identifying the most valuable direct comparisons—those that would fill critical gaps or strengthen weak links in the network [21].

Table 2: Summary of Network Geometries and Methodological Implications

| Geometry Type | Key Characteristics | Strengths | Limitations & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Star | Single central comparator; no direct links between peripherals. | Simple structure; easy to interpret. | All comparisons are indirect; relies entirely on transitivity; no way to check consistency. |

| Loop | Closed structure (e.g., triangle) with interventions directly connected. | Enables statistical check of consistency between direct and indirect evidence. | Detection of inconsistency requires investigation into its source (bias or diversity). |

| Complex/Asymmetrical | Multiple interconnected loops and side-arms; varied evidence distribution. | Robustness from borrowing strength; identifies evidence gaps for future research. | Interpretation is more complex; requires careful assessment of transitivity across the entire network. |

Methodological Protocols for Network Geometry Analysis

A rigorous NMA requires a structured approach to evaluating its geometry. The following protocol outlines key steps.

Data Collection and Network Diagram Creation

- Systematic Review: Conduct a comprehensive systematic review to identify all relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for the interventions of interest. This forms the evidence base.

- Define Nodes: Clearly define each intervention (node) to ensure they are clinically coherent. Grouping similar interventions (e.g., different doses of the same drug) requires clear justification.

- Plot the Network: Create a network diagram, typically using statistical software like R (with packages like

netmeta) or Bayesian software like WinBUGS/OpenBUGS [21] [23]. The diagram should visually represent all direct comparisons.

Evaluating Transitivity and Consistency

- Transitivity Assessment: Before analysis, compare the distribution of potential effect modifiers (e.g., patient baseline risk, study year, methodological quality) across the different direct comparisons. This is a qualitative/substantive evaluation [21].

- Consistency Assessment: Use statistical models to evaluate consistency in closed loops. Local methods (e.g., the Bucher method for a single loop) and global methods (e.g., design-by-treatment interaction model) can be applied. The presence of significant inconsistency necessitates exploration of its sources, which may include differences in trial populations, interventions, or outcome definitions [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network Meta-Analysis

| Item / Resource | Type | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Software Environment | A free, open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics. It is the primary platform for conducting frequentist and some Bayesian NMAs. |

netmeta package (R) |

Software Library | A widely used R package for conducting frequentist network meta-analyses. It performs meta-analysis, generates network plots, and evaluates inconsistency. |

| WinBUGS / OpenBUGS | Software Application | Specialized software for conducting complex Bayesian statistical analyses using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. It has been historically dominant for Bayesian NMA [21] [23]. |

| JAGS (Just Another Gibbs Sampler) | Software Application | A cross-platform alternative to BUGS for Bayesian analysis, often used with the R2jags package in R. |

| PRISMA-NMA Checklist | Methodological Guideline | (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for NMA): A reporting guideline to ensure the transparent and complete reporting of NMAs. |

| CINeMA (Confidence in NMA) | Web Application / Framework | A software and methodological framework for evaluating the confidence in the results from network meta-analysis, focusing on risk of bias, indirectness, and inconsistency. |

| 680C91 | 680C91, CAS:163239-22-3, MF:C15H11FN2, MW:238.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Garciniaxanthone E | Garciniaxanthone E | Garciniaxanthone E is a natural xanthone for research. Studies suggest potential in oncology and biochemistry. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. |

The interpretation of network geometry—from simple stars to complex, asymmetrical structures—is not a mere descriptive exercise but a core component of a valid and informative Mixed Treatment Comparison. The geometry dictates the strength of the evidence, the validity of the underlying assumptions of transitivity and consistency, and the confidence with which clinicians and policymakers can interpret the resulting treatment rankings and effect estimates. A thorough understanding of these structures, coupled with rigorous methodological protocols for their evaluation, is indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to navigate and contribute to the evolving landscape of evidence-based medicine.

Implementing MTC Models: Methodological Frameworks and Real-World Applications

Within the evolving landscape of comparative effectiveness research, mixed treatment comparison (MTC) models, also known as network meta-analysis, have become indispensable tools for evaluating the relative efficacy and safety of multiple treatments. These models synthesize evidence from both direct head-to-head comparisons and indirect comparisons, enabling a comprehensive ranking of treatment options even when direct evidence is sparse or absent [24] [25]. The statistical analysis of such complex networks can be approached through two primary philosophical and methodological paradigms: the Frequentist and Bayesian frameworks. The choice between them is not merely philosophical but has practical implications for model specification, computational burden, and the interpretation of results. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of these two approaches, grounded in the context of MTC models, to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate framework for their research objectives.

Methodological Foundations

Core Principles of Frequentist and Bayesian Inference

The Frequentist approach to statistics is based on the long-run behavior of estimators. It treats model parameters as fixed, unknown quantities. Inference is drawn by considering the probability of the observed data, or something more extreme, under a assumed null hypothesis (e.g., no treatment effect), which yields the well-known p-value. Confidence intervals are constructed to indicate a range of values that, over repeated sampling, would contain the true parameter value a certain percentage of the time (e.g., 95%) [26].

In contrast, the Bayesian framework treats parameters as random variables with associated probability distributions. It combines prior knowledge or belief about a parameter (encoded in the prior distribution) with the observed data (via the likelihood function) to form an updated posterior distribution. The posterior distribution fully encapsulates the uncertainty about the parameter after seeing the data [27]. This leads to intuitive probabilistic statements, such as "there is a 95% probability that the true treatment effect lies within this credible interval."

Application in Mixed Treatment Comparisons

In MTC models, both frameworks aim to estimate relative treatment effects across a network of evidence.

- The Frequentist Approach often employs multivariable logistic regression models with treatments and patient subgroups included as fixed or random effects. The analysis typically relies on maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to find the parameter values that make the observed data most probable [28].

- The Bayesian Approach typically employs hierarchical models and uses computational methods, most notably Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), to sample from the complex posterior distributions of the treatment effect parameters. A key advantage is the direct calculation of the probability that each treatment is the best, second-best, etc., based on the posterior distributions [27] [25].

Experimental Protocols: A Simulation Case Study