Managing Inconsistency in Network Meta-Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Detecting and Resolving Direct-Indirect Evidence Conflicts

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on handling inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence in Network Meta-Analysis (NMA).

Managing Inconsistency in Network Meta-Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Detecting and Resolving Direct-Indirect Evidence Conflicts

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on handling inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence in Network Meta-Analysis (NMA). As NMA becomes increasingly vital for comparing multiple treatments simultaneously, ensuring the validity of its findings through proper inconsistency management is crucial. The content explores the fundamental concepts of inconsistency, including the assumptions of transitivity and coherence that underpin NMA validity. It details established and emerging methodological approaches for detection and quantification, such as node-splitting, design-by-treatment interaction models, and novel evidence-splitting techniques. The guide further addresses practical troubleshooting strategies for when inconsistency is identified, including the use of meta-regression and sensitivity analyses. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of validation techniques and software implementation, empowering researchers to produce more reliable and clinically relevant evidence syntheses for informed decision-making in biomedical research.

Understanding Inconsistency: The Bedrock of Valid Network Meta-Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between heterogeneity and inconsistency in Network Meta-Analysis?

Heterogeneity refers to variability in the treatment effects between different studies that are investigating the same pairwise comparison (e.g., Treatment A vs. Treatment B). It is a concept inherited from conventional pairwise meta-analysis. Inconsistency, on the other hand, occurs when the direct evidence (e.g., from studies directly comparing A and C) conflicts with the indirect evidence (e.g., evidence for A vs. C obtained through a common comparator B, via A vs. B and B vs. C studies) [1]. In essence, heterogeneity exists within a treatment comparison, while inconsistency exists between different sources of evidence (direct and indirect) for the same treatment comparison [2] [1].

2. What are the primary causes of inconsistency in a network?

Inconsistency can arise from several factors, often related to differences in the studies that contribute to different comparisons in the network. Key causes include:

- Effect Modifiers: When the distribution of effect modifiers (e.g., disease severity, patient age, dose of a drug) differs across the sets of studies making different treatment comparisons [2].

- Bias: Different types of bias (e.g., optimism bias, publication bias, sponsorship bias) may act differently in studies of different comparisons [2].

- Protocol Differences: Fundamental differences in the versions of a treatment used in different comparisons (e.g., different doses or formulations of Treatment B in studies of A vs. B and studies of B vs. C) or differences in the settings or time periods in which studies were conducted [1].

3. What statistical methods are available to detect and quantify inconsistency?

Several statistical approaches have been developed, ranging from simple to complex. The table below summarizes the key methods, their approaches, and considerations for use.

Table 1: Key Statistical Methods for Assessing Inconsistency in NMA

| Method | Statistical Approach | What it Assesses | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loop-based Approach [3] | Calculates the difference between direct and indirect evidence in a treatment loop. Tests the statistical significance of this difference. | Inconsistency within closed loops of three treatments. | Simple but can be cumbersome in large networks due to multiple testing. Not designed for networks with multi-arm trials [2] [1]. |

| Node-Splitting [2] | Separates the evidence for a specific comparison into direct and indirect components and tests for a discrepancy between them. | Local, comparison-specific inconsistency. | Provides a direct assessment of which specific comparisons are inconsistent. Can be computationally intensive as it tests one comparison at a time [2]. |

| Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model [1] | A global model that accounts for inconsistency by introducing interaction terms between designs and treatments. | Global inconsistency across the entire network. | Considered a general framework that successfully addresses complications from multi-arm trials. It encompasses both loop and design inconsistency [1]. |

| Inconsistency Parameter Approach (Lu & Ades) [1] | A Bayesian hierarchical model that relaxes the consistency assumption by including specific inconsistency parameters. | Global inconsistency. | Model choice (which parameters to include) can be arbitrary and, in the presence of multi-arm trials, can depend on the order of treatments [2] [1]. |

| Net Heat Plot [4] | A graphical tool that temporarily removes each design (set of treatments compared) one-by-one to visualize its contribution to network inconsistency. | A visual assessment to locate potential sources of inconsistency. | The underlying calculations constitute an arbitrary weighting of evidence and may not reliably signal or locate inconsistency [2]. |

4. How does the presence of multi-arm trials affect inconsistency assessment?

Multi-arm trials (trials with more than two treatment groups) complicate the assessment of inconsistency. A key principle is that inconsistency cannot occur within a single multi-arm trial because the treatment effects within the trial are internally consistent by design [1]. Therefore, standard loop-inconsistency methods, which assume all trials are two-armed, are not adequate. Methods like the Design-by-Treatment Interaction model are specifically designed to handle networks that include multi-arm trials correctly [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Scenario 1: Your Network Contains a Closed Loop, and You Suspect Inconsistency

Problem: You have a network of interventions forming at least one closed loop (e.g., a triangle of A, B, and C, with studies for A-B, B-C, and A-C). You want to check if the direct and indirect evidence for one of the comparisons (e.g., A-C) are in agreement.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Visualize the Network: Begin by creating a network graph to understand the structure of your evidence. This helps identify all closed loops.

- Apply a Loop Inconsistency Test: For the loop in question (A-B-C), use the method described by Bucher et al. to calculate the inconsistency factor (IF) [3].

- Let

d_AB,d_BC, andd_ACbe the pooled direct estimates from meta-analyses of the A-B, B-C, and A-C studies, respectively. - The indirect estimate for A-C is:

ind_AC = d_AB + d_BC. - The inconsistency factor is:

IF = d_AC - ind_AC. - The variance of IF is:

var(IF) = var(d_AC) + var(d_AB) + var(d_BC). - A Z-test can be performed:

Z = IF / sqrt(var(IF)). A large absolute Z-value (e.g., |Z| > 1.96) suggests significant inconsistency in that loop.

- Let

- Confirm with Node-Splitting: To verify and localize the inconsistency, perform a node-split analysis for the A-C comparison. This will formally test the difference between the direct evidence for A-C and the indirect evidence for A-C obtained from the rest of the network [2].

- Investigate Clinically: If statistical inconsistency is found, investigate potential clinical or methodological reasons (e.g., differences in patient populations, interventions, or study quality across the A-B, B-C, and A-C studies) that could explain the conflict.

Scenario 2: You Need a Global Assessment of Inconsistency in a Complex Network

Problem: Your network has multiple treatments and complex loops, possibly including multi-arm trials. You need a single, overall test for inconsistency and to understand its distribution.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Fit a Consistency Model: First, fit a standard NMA model that assumes the consistency assumption holds throughout the network.

- Fit an Inconsistency Model: Next, fit a model that allows for inconsistency. The Design-by-Treatment Interaction model is a robust choice, especially if your network contains multi-arm trials [1].

- Compare Models: Statistically compare the fit of the consistency and inconsistency models. This is often done using the deviance information criterion (DIC) in a Bayesian framework. A lower DIC for the inconsistency model suggests a better fit, indicating that the consistency assumption may be violated. A large difference in DIC (e.g., > 5 points) is typically considered meaningful.

- Interpret and Explore: If global inconsistency is detected, use local methods like node-splitting or inspection of the inconsistency model parameters to identify which parts of the network are contributing most to the inconsistency.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Software and Methodological Tools for NMA Inconsistency Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

R package netmeta [5] |

A comprehensive package for conducting frequentist NMA. | Implements various statistical methods for NMA, including the net heat plot [4] and component NMA models. Provides functions for generating network graphs. |

| Bayesian Frameworks (WinBUGS/OpenBUGS/JAGS/Stan) [6] | Provides a flexible environment for fitting complex hierarchical models. | Essential for implementing models like the Lu & Ades inconsistency model [1] and the Design-by-Treatment model. Allows for full quantification of uncertainty. |

| Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model [1] | A statistical model to account for global inconsistency. | Provides a general framework for inconsistency that is not reliant on arbitrary loop choices and correctly handles multi-arm trials. |

| Node-Splitting Method [2] | A technique to assess local inconsistency for individual comparisons. | Directly separates and tests direct and indirect evidence for each comparison, helping to pinpoint the source of conflict in a network. |

Supporting Visualizations

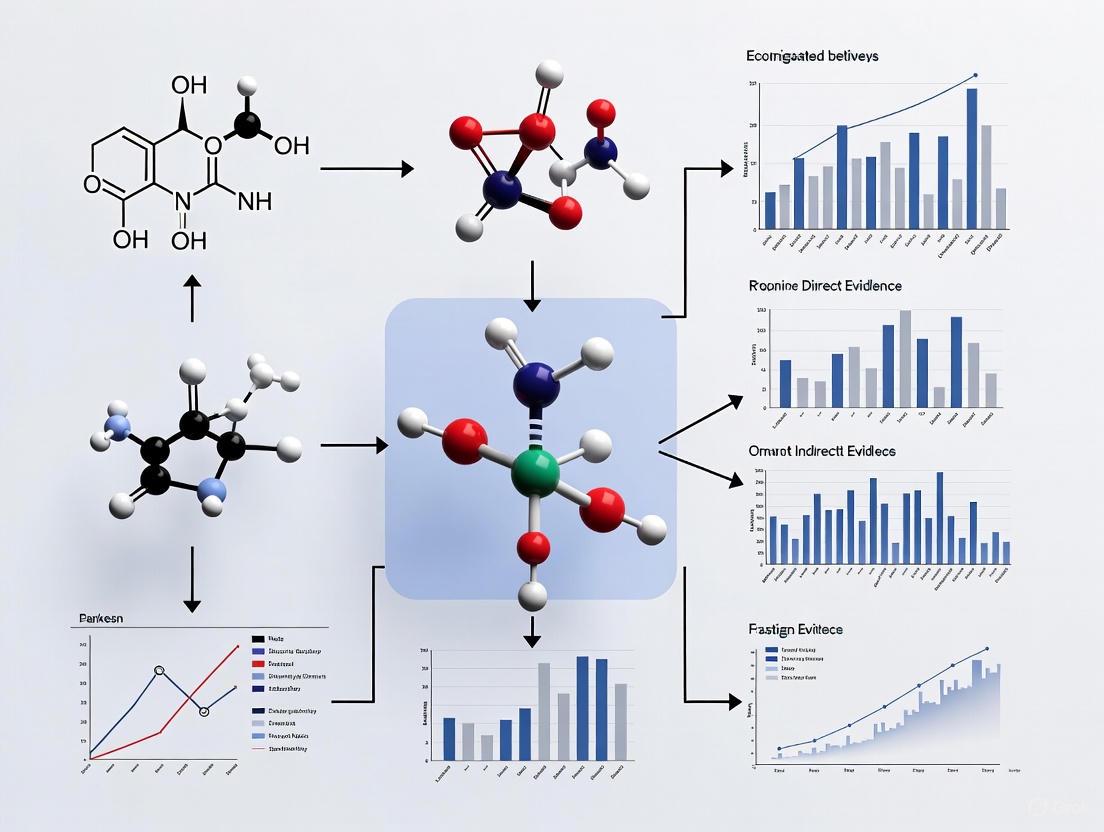

Diagram 1: Inconsistency Assessment Methods

Diagram 2: Loop Inconsistency Concept

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the core assumptions that ensure a Network Meta-Analysis is valid? The validity of an NMA rests on three critical, interconnected assumptions: transitivity, coherence (also known as consistency), and similarity. Transitivity and similarity are methodological assumptions about the included studies, while coherence is the statistical manifestation of these assumptions. If the studies in the network are similar enough (transitivity), then the direct and indirect evidence should agree (coherence) [7] [8] [9].

What should I do if my network shows significant inconsistency? Significant inconsistency indicates a violation of the transitivity assumption. You should [7] [9]:

- Re-examine Effect Modifiers: Investigate if study characteristics (PICO factors) are imbalanced across the treatment comparisons.

- Use Statistical Models: Employ models specifically designed to detect and handle inconsistency, such as the node-splitting method.

- Report the Findings: Clearly document the presence and extent of inconsistency in your results, as it affects the confidence in the network estimates.

How can the network's geometry itself be a source of bias? The structure of the evidence network (its geometry) can reveal biases in the underlying research. For example, if most trials only compare new drugs to an old standard rather than to each other, the network will be star-shaped. This can reflect commercial sponsorship biases where manufacturers choose favorable comparators. Such imbalances are a threat to transitivity and should be discussed in your review [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing and Resolving Incoherence

Incoherence occurs when different sources of evidence (e.g., direct and indirect) for the same treatment comparison disagree statistically [7]. Follow this diagnostic protocol:

Table: Protocol for Investigating Incoherence

| Step | Action | Key Tool/Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm | Check if direct and indirect estimates disagree. | Node-splitting method; Incoherence models (e.g., side-split method) [7]. |

| 2. Investigate | Search for clinical/methodological dissimilarities (effect modifiers). | Subgroup analysis or meta-regression on potential effect modifiers [7] [9]. |

| 3. Act | Based on findings, present results and qualify conclusions. | Report separate direct/indirect estimates; use inconsistency models; discuss limitations [7]. |

Evaluating the Transitivity Assumption

Transitivity cannot be tested statistically but must be assessed qualitatively during the review process. Use this checklist to evaluate its plausibility [8] [9]:

Table: Checklist for Assessing Transitivity

| Aspect to Evaluate | Guiding Question | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Would the participants in studies for different comparisons be eligible for the other comparisons in the network? | Define strict, uniform inclusion criteria. |

| Interventions (I) | Are the interventions and their delivery similar across comparisons? | Standardize the definition of each treatment node. |

| Comparators (C) | Are the control groups comparable in their standard of care? | Ensure common comparators are equivalent. |

| Outcomes (O) | Are the outcome measurements and timing similar? | Pre-define a core outcome set for the network. |

| Study Methods | Are the study designs and risk of bias similar? | Exclude studies with a high risk of bias that may introduce confounding. |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Table: Summary of Key Statistical Measures for Coherence

| Statistical Measure | Formula | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect Estimate | (\hat{\theta}{\text{A,C}}^{\text{indirect}} = \hat{\theta}{\text{B,A}}^{\text{direct}} - \hat{\theta}_{\text{B,C}}^{\text{direct}}) [8] | The mathematically derived effect of A vs. C via common comparator B. | Foundational for all indirect evidence. |

| Variance of Indirect Estimate | (\text{Var} (\hat{\theta}{\text{A,C}}^{\text{indirect}}) = \text{Var} (\hat{\theta}{\text{B,A}}^{\text{direct}}) + \text{Var} (\hat{\theta}_{\text{B,C}}^{\text{direct}})) [8] | Quantifies the increased uncertainty of an indirect estimate. | Explains why indirect evidence is less precise. |

| Incoherence (ω) | ( \omega = \hat{\theta}{\text{A,C}}^{\text{direct}} - \hat{\theta}{\text{A,C}}^{\text{indirect}} ) | The difference between direct and indirect evidence. A value significantly different from zero indicates incoherence [7]. | Used in statistical models to measure inconsistency (e.g., design-by-treatment interaction model). |

Experimental Protocol: Node-Splitting Analysis This protocol is used to statistically test for local incoherence at specific comparisons [7].

- Objective: To detect disagreement between direct and indirect evidence for a specific treatment comparison.

- Method: For a given comparison (e.g., A vs. C), the model "splits" the evidence into two distinct parameters: one for the direct evidence and one for the indirect evidence.

- Analysis: The model estimates the difference between these two parameters. A statistically significant difference (p-value < 0.05) suggests incoherence for that comparison.

- Software: Can be implemented in Bayesian or frequentist software packages like

gemtcin R orBUGS/JAGS.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for NMA

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| PRISMA-NMA Checklist | Ensures comprehensive and transparent reporting of the systematic review and NMA [9]. |

| Risk of Bias Tool (e.g., RoB 2.0) | Assesses the methodological quality of individual randomized trials, a key factor for assessing similarity/transitivity [7]. |

Statistical Software (R with netmeta, gemtc) |

Performs all statistical analyses, including meta-analysis, network estimation, and inconsistency checks [8]. |

| Network Geometry Map | A visual representation of the evidence base, highlighting well-connected treatments and evidence gaps [7] [9]. |

| SKA-111 | SKA-111, MF:C12H10N2S, MW:214.29 g/mol |

| SR9238 | SR9238, MF:C31H33NO7S2, MW:595.7 g/mol |

Logical and Conceptual Workflows

Transitivity and Coherence Relationship

Incoherence Investigation Workflow

In Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), inconsistency refers to statistical disagreement between direct and indirect evidence. This technical guide explores the sources and common causes of inconsistency, providing researchers with troubleshooting methodologies to identify and address these issues in clinical networks.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is inconsistency in Network Meta-Analysis? Inconsistency occurs when direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (from a connected network of trials) provide conflicting estimates of treatment effects [2]. This represents a violation of the consistency assumption, which is fundamental to the validity of NMA results [10].

How common is inconsistency in published NMAs? Empirical evidence from 201 published networks shows that evidence of inconsistency is present in a significant proportion of analyses [11] [12]:

Table: Prevalence of Inconsistency in Published Networks (n=201)

| Evidence Threshold | Prevalence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| p-value < 0.05 | 14% of networks | Strong evidence of inconsistency |

| p-value < 0.10 | 20% of networks | Evidence of inconsistency |

Networks with many studies comparing few interventions were more likely to show evidence of inconsistency, likely due to higher statistical power to detect differences [12].

What are the primary sources of inconsistency?

- Violation of Transitivity: This occurs when the distribution of effect modifiers (patient characteristics, trial methodology, etc.) differs across treatment comparisons [10]. For example, if trials comparing Treatment A vs. B enrolled predominantly severe cases, while trials for A vs. C enrolled mild cases, the indirect comparison of B vs. C would be biased.

- Bias in Direct Comparisons: Inconsistency can arise when specific biases, such as publication bias, sponsorship bias, or optimism bias, affect certain direct comparisons differently within the network [2].

What is the relationship between heterogeneity and inconsistency? There is an inverse association between heterogeneity and the statistical power to detect inconsistency [11] [12]. High heterogeneity makes direct and indirect estimates less precise, which can mask underlying inconsistency. When inconsistency is present, the standard consistency model often displays higher estimated heterogeneity than an inconsistency model [12].

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Inconsistency

Protocol 1: Design-by-Treatment (DBT) Interaction Test

Purpose: To provide a global assessment of inconsistency across the entire network [11] [12].

Methodology:

- Model Fitting: Fit a random-effects DBT model that incorporates an extra parameter to account for variability due to inconsistency beyond what is expected from heterogeneity.

- Hypothesis Testing: Test all inconsistency parameters globally using a Wald-type chi-squared test.

- Interpretation: A significant p-value (commonly <0.05 or <0.10) indicates evidence of inconsistency in the network. This method is particularly valuable as it is insensitive to the parameterization of multi-arm trials [11].

Protocol 2: Node-Splitting Method

Purpose: To perform a local, comparison-specific assessment of inconsistency [2].

Methodology:

- Evidence Separation: For a specific treatment comparison (e.g., B vs. C), separate the evidence into direct (from trials directly comparing B and C) and indirect (formed via other treatments in the network, such as A) components.

- Estimate Calculation: Calculate the direct estimate, ( \hat{d}{BC}^{Dir} ), and the indirect estimate, ( \hat{d}{BC}^{Ind} = \hat{d}{AC}^{Dir} - \hat{d}{AB}^{Dir} ).

- Discrepancy Assessment: Assess the discrepancy between the direct and indirect estimates. The inconsistency, ( \hat{\omega}{BC} ), is calculated as: ( \hat{\omega}{BC} = \hat{d}{BC}^{Dir} - \hat{d}{BC}^{Ind} ) with variance: ( Var(\hat{\omega}{BC}) = Var(\hat{d}{BC}^{Dir}) + Var(\hat{d}{AB}^{Dir}) + Var(\hat{d}{AC}^{Dir}) ) [10].

- Statistical Testing: An approximate test for inconsistency is performed by referring ( z{BC} = \frac{\hat{\omega}{BC}}{\sqrt{Var(\hat{\omega}_{BC})}} ) to the standard normal distribution.

Table: Comparison of Key Methods for Detecting Inconsistency

| Method | Scope of Assessment | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design-by-Treatment (DBT) | Global (entire network) | Insensitive to parameterization of multi-arm trials [11] | Does not locate the source of inconsistency |

| Node-Splitting | Local (specific comparison) | Pinpoints which comparisons are inconsistent [2] | Computationally intensive in large networks |

| Bucher Method | Local (single loop) | Simple calculation for a 3-treatment loop [10] | Not suitable for complex networks with multi-arm trials |

| Cochran's Q | Global (entire network) | Familiar statistic from pairwise meta-analysis [2] | Does not distinguish between heterogeneity and inconsistency |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Detected Inconsistency

If inconsistency is detected in your network:

- Investigate Effect Modifiers: Systematically check for imbalances in patient-level (e.g., disease severity, age) or trial-level (e.g., year, duration, risk of bias) characteristics across the different direct comparisons [10].

- Subgroup and Meta-Regression Analyses: If potential effect modifiers are identified, perform subgroup analyses or network meta-regression to adjust for them and explore if inconsistency is reduced.

- Use Inconsistency Models: Consider using models that explicitly account for inconsistency, such as the Bayesian hierarchical model with inconsistency parameters proposed by Lu and Ades [2].

- Report and Interpret with Caution: Clearly report the findings and degree of inconsistency. If the source cannot be explained or resolved, interpret the NMA results with caution, as they may be unreliable.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents and Methods for Inconsistency Investigation

| Tool / Method | Primary Function | Application in Inconsistency Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Design-by-Treatment Model | Statistical Model | Provides a global test for the presence of inconsistency in the entire network [11]. |

| Node-Splitting | Statistical Method | Separates direct and indirect evidence for a specific comparison to test their agreement [2]. |

| Network Diagram | Visual Tool | Helps visualize the network structure, identify independent loops, and hypothesize where inconsistency may arise [10]. |

| Meta-Regression | Analytical Technique | Adjusts for continuous effect modifiers to see if they explain the observed inconsistency [10]. |

Stata (network suite) |

Software Command | Fits NMA models, including the DBT model, for inconsistency assessment [11]. |

R (netmeta package) |

Software Package | Performs NMA and includes functions for local and global inconsistency tests [11]. |

| T-3364366 | T-3364366, MF:C18H16F3N3O3S2, MW:443.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TAK-828F | TAK-828F | TAK-828F is a potent, selective, orally available RORγt inverse agonist for autoimmune disease research. This product is for research use only (RUO). |

Visualizing the Pathway to Inconsistency

Sources of Inconsistency Flowchart: This diagram illustrates the logical pathway from underlying causes, like imbalanced effect modifiers or specific biases, to the emergence of statistical inconsistency, ultimately compromising NMA validity [10] [2].

Inconsistency Investigation Workflow: A decision flowchart outlining the recommended steps for investigating inconsistency, starting with a global test and proceeding to local methods if needed [11] [2].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

What is inconsistency in Network Meta-Analysis and why is it a problem?

Inconsistency occurs when the direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (estimated through a common comparator) for a treatment comparison are in statistical disagreement [2]. This poses a significant problem because it can result in biased treatment effect estimates, compromising the reliability of the NMA and any clinical conclusions or decisions derived from it [2]. Inconsistency may arise from biases in direct comparisons (like publication bias) or when trial populations differ in important characteristics that modify treatment effects (effect modifiers) [2].

How common is inconsistency in published Network Meta-Analyses?

Empirical evidence from a large sample of published NMAs indicates that inconsistency is a relatively frequent issue [11]. The table below summarizes the prevalence of evidence of inconsistency based on the Design-by-Treatment (DBT) interaction model:

| Evidence Threshold (DBT p-value) | Prevalence in Published NMAs | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 0.05 | 14% of networks [11] | Strong evidence against consistency |

| Less than 0.10 | 20% of networks [11] | Evidence against consistency |

Networks that include many studies but compare few interventions are more likely to show evidence of inconsistency, partly because they produce more precise estimates and have higher power to detect differences between designs [11].

What are the main statistical methods to detect inconsistency?

Several statistical approaches exist to assess inconsistency, ranging from simple to complex methods. The table below compares the key techniques:

| Method | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Cochran's Q Statistic [2] | Global assessment of heterogeneity/inconsistency | A common method for assessing heterogeneity; its generalized form can quantify inconsistency across the whole network. |

| Loop Inconsistency Approach [2] | Local assessment in loops of three treatments | Involves calculating the difference between direct and indirect evidence in a treatment loop; can be cumbersome in large networks due to multiple testing. |

| Design-by-Treatment (DBT) Interaction Model [11] | Global assessment for the entire network | Provides a global test insensitive to the parameterization of multi-arm trials; p-value indicates evidence against consistency. |

| Inconsistency Parameter Approach (Lu & Ades) [2] | Model-based assessment | A Bayesian hierarchical model that includes inconsistency parameters in each loop; model choice (fixed/random effects) can be arbitrary. |

| Node-Splitting [2] | Local, comparison-specific assessment | Separates direct and indirect evidence for a specific treatment comparison to assess their discrepancy. |

| Net Heat Plot [2] | Graphical identification of inconsistency sources | A graphical tool that displays the contribution of each design to network inconsistency by temporarily removing designs one at a time. |

The net heat plot did not signal inconsistency, but other methods did. Why?

This discrepancy can occur because the net heat plot does not reliably signal inconsistency [2]. The calculations underlying the net heat plot constitute an arbitrary weighting of the direct and indirect evidence, which may be misleading. Therefore, the absence of a signal in a net heat plot should not be interpreted as the absence of inconsistency. It is recommended to use multiple statistical methods to assess inconsistency rather than relying on a single approach [2].

What should I do if I detect significant inconsistency in my network?

If inconsistency is detected, you should not ignore it. The following steps are recommended:

- Investigate Clinical and Methodological Causes: Explore potential effect modifiers (e.g., differences in patient populations, intervention doses, or outcome definitions) across studies forming the direct and indirect evidence [2].

- Check for Transitivity Violations: Assess whether the distribution of these effect modifiers is similar across the different treatment comparisons [11].

- Consider Inconsistency Models: If inconsistency cannot be resolved, consider using statistical models that account for it, such as the inconsistency parameter approach or node-splitting models [2]. Note that in the presence of inconsistency, the standard consistency model may display higher heterogeneity than the inconsistency model [11].

- Interpret Results with Caution: Acknowledge the presence of inconsistency in the limitations section and interpret the NMA results with caution, as they may be less reliable.

Experimental Protocols for Key Inconsistency Assessments

Protocol 1: Global Inconsistency Test via Design-by-Treatment (DBT) Interaction Model

Purpose: To assess inconsistency across the entire network of interventions. Methodology Summary:

- Model Framework: Synthesize evidence using a model that incorporates extra variability attributable to inconsistency, beyond what is expected from heterogeneity or random error. This model evaluates the potential conflict between studies with different sets of interventions (designs) [11].

- Hypothesis Testing: Test the null hypothesis that the network is consistent.

- Test Statistic: Use a Wald-type chi-squared test statistic. A p-value below a pre-specified threshold (e.g., 0.05 or 0.10) provides evidence against the consistency assumption [11].

- Heterogeneity Estimation: Estimate the between-study variance (heterogeneity) using estimators like DerSimonian and Laird (DL) or Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) [11].

Protocol 2: Local Inconsistency Test via Node-Splitting

Purpose: To assess inconsistency for a specific treatment comparison within the network. Methodology Summary:

- Evidence Separation: For the treatment comparison of interest (e.g., A vs. B), separate the available evidence into two parts:

- The direct evidence from studies that directly compare A and B.

- The indirect evidence for A vs. B, estimated from the remaining network (e.g., via a common comparator C).

- Effect Estimation: Estimate the treatment effect for A vs. B from both the direct and the indirect evidence.

- Discrepancy Assessment: Statistically assess the discrepancy (difference) between the direct and indirect estimates. A significant difference indicates local inconsistency for that comparison [2].

Logical Relationship of Inconsistency Assessment Methods

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing inconsistency in a Network Meta-Analysis, showing how global and local methods interrelate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Inconsistency Investigation

| Tool or Method | Primary Function | Key Features and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Design-by-Treatment (DBT) Interaction Model [11] | Global inconsistency test | Provides a single p-value for the entire network; insensitive to parameterization of multi-arm trials. |

| Node-Splitting Model [2] | Local inconsistency test | Allows pinpointing which specific treatment comparisons are inconsistent. |

| Loop Inconsistency Approach [2] | Local inconsistency test | Assesses inconsistency in loops of three treatments; may require adjustment for multiple testing. |

| Cochran's Q Statistic [2] | Global heterogeneity/inconsistency measure | A generalized statistic that can quantify both within-design heterogeneity and between-design inconsistency. |

| Net Heat Plot [2] | Graphical exploration | A visual aid for exploring potential sources of inconsistency; should not be relied upon alone due to reliability concerns. |

| Statistical Software (R/Stata) | Analysis platform | Implementations available in packages like netmeta in R and the network suite in Stata [11]. |

| TAMRA-PEG4-Alkyne | TAMRA-PEG4-Alkyne|Click Chemistry Reagent | TAMRA-PEG4-Alkyne is a CuAAC reagent for fluorescent bioimaging and nucleotide labeling. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| TAN-452 | TAN-452 Chemical Reagent For Research | TAN-452 is a high-purity research reagent for biochemical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the primary purpose of a node-splitting analysis in Network Meta-Analysis?

A node-splitting analysis is used to evaluate potential inconsistency in a network meta-analysis [13]. It works by splitting the evidence for a specific treatment comparison into two parts: the direct evidence (from studies that directly compare the two treatments) and the indirect evidence (from the rest of the network) [13] [14]. A separate estimate is obtained for each part, and the agreement between these direct and indirect estimates is then statistically assessed. Significant disagreement indicates local inconsistency for that particular comparison [13].

2. How do I decide which treatment comparisons to split in my network?

Choosing which comparisons to split can be complex, especially in networks that include multi-arm trials. An unambiguous decision rule has been developed to automate this process [13]. This rule ensures that:

- You only split comparisons that are part of potentially inconsistent loops in the network.

- All potentially inconsistent loops in the network are investigated.

- Problems with the parameterization of multi-arm trials are circumvented, making model generation straightforward [13].

3. What are the different ways to parameterize a node-splitting model, and why does it matter?

When multi-arm trials are involved, there are different ways to assign the inconsistency parameter, and this choice can yield different results [14]. The main parameterizations are:

- Symmetrical: Assumes that both treatments in the comparison contribute equally to the inconsistency.

- Asymmetrical (one-treatment): Assumes that only one of the two treatments contributes to the inconsistency [14]. Your choice should be guided by your understanding of the treatments and the network structure, as each method makes slightly different assumptions about the source of inconsistency.

4. What should I do if my node-splitting analysis detects significant inconsistency?

The detection of significant inconsistency warrants a careful investigation. The statistical analysis alone does not resolve the problem; you must try to understand its source [13]. This involves:

- A thoughtful re-evaluation of the included trials, focusing on differences in design, population characteristics, or risk of bias that might explain the discrepant results.

- If a confounding factor is identified, you may address it via sensitivity analysis (e.g., excluding a problematic subset of trials) or meta-regression.

- Unexplained and significant inconsistency may mean that the results of the network meta-analysis are unreliable and must be interpreted with extreme caution [13].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Bayesian Node-Splitting Model

This protocol outlines the steps for evaluating inconsistency using a Bayesian node-splitting model [13].

Objective: To assess the inconsistency for a specific treatment comparison (e.g., treatment X vs. Y) by separating direct and indirect evidence.

Methodology:

- Model Specification: For the comparison of interest ( d{x,y} ), define two parameters: a parameter for the direct evidence ( d{x,y}^{dir} ) and a parameter for the indirect evidence ( d_{x,y}^{ind} ) [13].

- Data Separation: The likelihood for the direct evidence is based only on studies that directly compare X and Y. The indirect evidence is informed by the remaining studies in the network.

- Prior Distributions: Specify non-informative or weakly informative prior distributions for the model parameters, including the heterogeneity variance.

- Estimation: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling in software like WinBUGS, JAGS, or Stan to estimate the posterior distributions of ( d{x,y}^{dir} ) and ( d{x,y}^{ind} ) [13].

- Assessment: Compare the posterior distributions of the direct and indirect estimates. The hypothesis of consistency is that ( d{x,y}^{dir} = d{x,y}^{ind} ). This can be evaluated by checking if the credible interval of their difference includes zero or by calculating a Bayesian p-value [13].

Table 1: Key Outputs from a Bayesian Node-Splitting Analysis

| Output Parameter | Description | How to Interpret Results |

|---|---|---|

| ( d_{x,y}^{dir} ) | The relative treatment effect estimate from direct evidence. | Compare the posterior mean/median and 95% credible interval (CrI) with the indirect estimate. |

| ( d_{x,y}^{ind} ) | The relative treatment effect estimate from indirect evidence. | Compare the posterior mean/median and 95% CrI with the direct estimate. |

| ( d{x,y}^{dir} - d{x,y}^{ind} ) | The difference between direct and indirect estimates. | Inconsistency is present if the 95% CrI for this difference does not contain zero. |

| Heterogeneity (τ²) | The estimate of between-study variance. | A high value may complicate the detection of inconsistency [13]. |

Protocol 2: Applying a Frequentist Side-Splitting Model using GLMM

This protocol describes an alternative, frequentist approach to node-splitting using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) [14].

Objective: To evaluate direct-indirect inconsistency using an arm-based, frequentist model framework.

Methodology:

- Model Framework: Use an arm-based generalized linear mixed model. This models study-specific absolute effects and assumes random intercepts [14] [15].

- Parameterization Choice: Decide on the inconsistency parameterization:

- Symmetrical: Inconsistency is split between both treatments.

- Asymmetrical: Inconsistency is assigned to one of the two treatments [14].

- Model Fitting: Fit the model using frequentist software capable of handling GLMMs, such as the

netmetapackage in R [14]. - Hypothesis Testing: Assess the statistical significance of the inconsistency factor using a Wald test or likelihood ratio test. A significant p-value indicates evidence of inconsistency.

Table 2: Comparison of Node-Splitting Model Approaches

| Feature | Bayesian Node-Splitting [13] | Frequentist Side-Splitting (GLMM) [14] |

|---|---|---|

| Framework | Bayesian statistics | Frequentist statistics |

| Output | Posterior distributions and credible intervals | Point estimates, confidence intervals, and p-values |

| Handling of Multi-arm Trials | Addressed via decision rules for model generation [13] | Different parameterizations (symmetrical/asymmetrical) can yield different results [14] |

| Interpretation | Probability of inconsistency given the data | Statistical significance of the inconsistency factor |

| Common Software | WinBUGS, JAGS, Stan | R (e.g., netmeta package) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for NMA Inconsistency Analysis

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use in NMA |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Model Generation Algorithm | A decision rule that automatically selects which comparisons to split and generates the corresponding models [13]. | Eliminates manual work in node-splitting; ensures all potentially inconsistent loops are investigated. |

| Contrast-Based (CB-NMA) Model | A model that focuses on synthesizing study-specific relative effects (contrasts) and assumes fixed study-specific intercepts [15]. | The traditional framework for implementing consistency and node-splitting models [13]. |

| Arm-Based (AB-NMA) Model | A model that uses study-specific absolute effects and assumes random intercepts, offering greater flexibility in estimands [15]. | Can be used to implement a frequentist side-splitting model for inconsistency [14]. |

| Composite Likelihood Method | An advanced statistical approach that provides accurate inference without requiring knowledge of typically unreported within-study correlations [15]. | Helps overcome a key challenge in NMA that can lead to biased estimates if ignored. |

| PRISMA-NMA Guidelines | The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Network Meta-Analyses [16]. | Ensures complete and transparent reporting of your NMA, including methods for assessing inconsistency. |

| TASP0390325 | TASP0390325, CAS:1642187-96-9, MF:C25H30Cl2FN5O, MW:554.4444 | Chemical Reagent |

| Boc-Aminooxy-PEG2 | Boc-Aminooxy-PEG2, CAS:1807503-86-1, MF:C9H19NO5, MW:221.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Evidence Flow and Inconsistency

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental concept of separating evidence in a node-splitting analysis.

This workflow outlines the decision-making process when inconsistency is detected.

Detection and Quantification: A Toolkit for Identifying Inconsistency

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core difference between node-splitting and the Bucher method for evaluating inconsistency in NMA?

Both methods assess inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence but differ fundamentally in approach. The Bucher method is a frequentist approach that performs adjusted indirect comparisons for a single treatment contrast in a loop of evidence, providing a single inconsistency estimate [17]. Node-splitting is a more general method, available in both Bayesian and frequentist frameworks, that separates direct and indirect evidence for a particular comparison and tests for their disagreement [13] [14]. It can evaluate multiple comparisons within a network and is particularly useful for identifying the specific location of inconsistencies [13].

Q2: When implementing node-splitting for a treatment comparison involved in multi-arm trials, I get different results depending on the parameterization. Why does this happen, and how should I proceed?

This occurs because multi-arm trials introduce ambiguity in how the inconsistency parameter is assigned [14]. Different parameterizations make different assumptions:

- Asymmetric parameterization assumes only one of the two treatments in the contrast contributes to the inconsistency.

- Symmetric parameterization assumes both treatments contribute to the inconsistency [14].

There is no universal "correct" choice. You should select the parameterization that best aligns with your clinical knowledge of the evidence network. The symmetric method is often preferred when there is no a priori reason to suspect one treatment over the other is the source of inconsistency.

Q3: My node-splitting analysis fails to run, citing disconnected nodes. What does this mean, and how can I fix it?

This error occurs when splitting the specified comparison would result in part of the network becoming disconnected from the reference treatment, making the indirect estimate incalculable [18]. To resolve this:

- Check your network connectivity using network graphs.

- Ensure that all treatments are connected through a path of comparisons.

- If using software, set the

drop.disconargument toTRUE(if available) to automatically drop disconnected treatments, though this should be done with caution as it alters the evidence base for the analysis [18]. - Consider selecting an alternative comparison to split that maintains network connectivity.

Q4: The Bucher method identified significant inconsistency in a loop. What are the potential next steps?

A significant inconsistency factor (IF) indicates that direct and indirect estimates for a contrast are statistically different. You should:

- Scrutinize the trials forming the direct and indirect evidence for clinical, methodological, or demographic dissimilarities that might explain the discrepancy.

- Check for the presence of effect modifiers across studies.

- Consider using meta-regression or subgroup analysis to account for identified differences, if sufficient data are available.

- Report the inconsistency and interpret the NMA results for the affected comparisons with extreme caution. Unexplained significant inconsistency may invalidate the consistency assumption for that part of the network [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Automated Selection of Comparisons for Node-Splitting

Problem: In a complex network, it is labor-intensive to decide which comparisons to split, and manual selection is prone to error and may miss important loops [13].

Solution: Implement a pre-specified decision rule to automatically select comparisons.

- Step 1: Use an algorithm to identify all closed loops in the evidence network where independent sources of evidence exist [13] [18].

- Step 2: Apply a decision rule that selects only one comparison per loop to split, typically the one with the most direct evidence or the one of primary clinical interest. A valid rule ensures all potentially inconsistent loops are investigated without redundancy [13].

- Step 3: Automated model generation can then be used to fit the node-splitting models for the selected comparisons, significantly reducing manual effort [13].

Issue 2: Handling Multi-Arm Trials in Node-Splitting

Problem: Results from a node-split are sensitive to how multi-arm trials are handled, leading to different conclusions based on parameterization [14].

Solution: Understand and correctly specify the model for multi-arm trials.

- Step 1: Identify all treatment comparisons in the network that are informed by at least one multi-arm trial.

- Step 2: Choose a parameterization method based on your assumptions about the source of inconsistency:

- Asymmetric Method: Use if you hypothesize that inconsistency originates from a single specific treatment in the comparison.

- Symmetric Method: Use if you believe both treatments contribute equally to the inconsistency. This is often the default when no prior hypothesis exists [14].

- Step 3: In your statistical code, ensure the covariance structure of multi-arm trials is correctly specified (the covariance is typically σ²/2 in a homogeneous variance model) [13]. Use software that explicitly allows for this specification.

Table: Comparison of Node-Splitting Parameterizations for Multi-Arm Trials

| Parameterization Type | Underlying Assumption | Best Use Case | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric | Inconsistency is attributable to a single treatment in the contrast being split. | When clinical knowledge suggests one treatment's effect is estimated differently across trial designs. | Results differ depending on which treatment is assigned the inconsistency parameter. |

| Symmetric | Both treatments in the contrast contribute to the inconsistency. | The default choice when there is no strong prior hypothesis about the source of inconsistency [14]. | Provides a single, averaged estimate of the direct-indirect difference. |

| Boc-Aminoxy-PEG4-OH | Boc-Aminoxy-PEG4-OH|PROTAC Linker|918132-14-6 | Bench Chemicals | |

| Propargyl-PEG2-NHBoc | Propargyl-PEG2-NHBoc, CAS:869310-84-9, MF:C12H21NO4, MW:243.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Issue 3: Interpreting Conflicting Results Between Global and Local Inconsistency Tests

Problem: A global test (e.g., design-by-treatment interaction model) finds significant inconsistency, but node-splitting finds no significant local inconsistencies.

Solution: This pattern suggests that inconsistency may be diffusely distributed across the entire network rather than localized in specific loops [13].

- Step 1: Do not ignore the global test. It has power to detect diffuse inconsistency that local tests might miss.

- Step 2: Re-examine the network for clinical or methodological heterogeneity, such as differences in patient populations, dosages, or study designs that are widespread across the network.

- Step 3: Consider using a meta-regression or subgroup analysis to explore potential effect modifiers if the global test is significant.

- Step 4: If no explanation is found, the results of the NMA should be interpreted with caution, and the uncertainty from the global inconsistency should be reflected in the conclusions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Node-Splitting Analysis

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for performing a node-splitting analysis to evaluate inconsistency at the treatment comparison level [13] [18].

Objective: To split the evidence for a given treatment comparison into direct and indirect components and statistically test their discrepancy.

Materials & Software: Statistical software with NMA capabilities (e.g., R using the gemtc or MBNMAdose packages, OpenBUGS, JAGS).

Procedure:

Model Specification:

- For the comparison of interest (e.g., A vs. B), define two parameters:

d_AB_directandd_AB_indirect. - Specify a model where the

d_AB_directis informed only by studies that directly compare A and B. - The

d_AB_indirectis informed by the rest of the network, estimated via the consistency relations from the other basic parameters [13].

- For the comparison of interest (e.g., A vs. B), define two parameters:

Model Fitting:

- Fit the model using Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods.

- Use vague priors for the basic parameters and the heterogeneity variance.

- Run multiple chains (e.g., 3) to assess convergence.

Output and Calculation:

- The key output is the posterior distribution of the difference between the direct and indirect estimates:

d_AB_direct - d_AB_indirect. - Calculate the posterior mean and 95% Credible Interval (CrI) for this difference.

- The key output is the posterior distribution of the difference between the direct and indirect estimates:

Interpretation:

- If the 95% CrI for the difference includes 0, there is no statistically significant inconsistency between the direct and indirect evidence for the comparison A vs. B.

- A 95% CrI that excludes 0 indicates significant local inconsistency.

Protocol 2: Executing the Bucher Loop-Based Method

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing the Bucher method, an adjusted indirect comparison for a single loop of evidence [17].

Objective: To obtain an indirect estimate of a treatment effect and compare it with the direct estimate to calculate an inconsistency factor.

Materials & Software: Standard statistical software (e.g., R, Stata, SAS) or even spreadsheet software capable of performing basic meta-analytic calculations.

Procedure:

Define the Loop: Identify a closed loop of three treatments (A, B, C) and the three pairwise comparisons (A vs. B, A vs. C, B vs. C). The loop must be informed by independent sources of evidence (e.g., from different sets of trials).

Extract Effect Estimates:

- For each of the three pairwise comparisons, obtain the pooled effect estimate (e.g., log odds ratio, mean difference) and its standard error from pair-wise meta-analyses or from the NMA consistency model.

Calculate the Indirect Estimate:

- The indirect estimate for A vs. B (for example) is calculated as:

Effect_AB_indirect = Effect_AC - Effect_BC. - The variance of the indirect estimate is:

Var(Effect_AB_indirect) = Var(Effect_AC) + Var(Effect_BC).

- The indirect estimate for A vs. B (for example) is calculated as:

Calculate the Inconsistency Factor (IF):

IF_AB = Effect_AB_direct - Effect_AB_indirect.- The variance of the IF is:

Var(IF_AB) = Var(Effect_AB_direct) + Var(Effect_AB_indirect).

Statistical Test:

- A 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for the IF is calculated as:

IF_AB ± 1.96 * sqrt(Var(IF_AB)). - If the 95% CI excludes 0, the inconsistency is statistically significant at the 5% level.

- A 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for the IF is calculated as:

Table: Data Collection Table for Bucher Method (Example: Log Odds Ratios)

| Comparison | Direct Estimate (logOR) | Variance of Direct Estimate | Source Studies | Indirect Estimate (logOR) | Variance of Indirect Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A vs. B | -0.45 | 0.05 | Studies 1, 2, 3 | Effect_AC - Effect_BC = -0.20 |

Var(AC) + Var(BC) = 0.03 |

| A vs. C | -0.60 | 0.02 | Studies 4, 5 | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| B vs. C | -0.40 | 0.01 | Studies 6, 7 | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Inconsistency Factor (A vs. B) | -0.45 - (-0.20) = -0.25 |

0.05 + 0.03 = 0.08 |

95% CI: -0.25 ± 1.96√0.08 = [-0.80, 0.30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents and Software for Inconsistency Analysis in NMA

| Item Name | Type | Specification / Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

R gemtc package |

Software Library | Provides a complete suite for Bayesian NMA, including node-splitting [13]. | Used for model specification, MCMC sampling, and results extraction. |

R MBNMAdose package |

Software Library | Contains the nma.nodesplit() function for performing node-splitting on a given network [18]. |

Allows specification of likelihood, link function, and random/common effects. |

| JAGS / OpenBUGS | Software | Bayesian analysis software used for Gibbs sampling. Can be called from R. | Provides the computational engine for fitting complex Bayesian hierarchical models. |

| Effect Size Data | Data Input | Pooled effect estimates and their variances (e.g., Log Odds Ratio, Hazard Ratio, Mean Difference). | The fundamental data for performing the Bucher method or feeding into NMA models. |

| Homogeneous Variance Prior | Statistical Parameter | The common between-study heterogeneity variance (τ²) assumed across the network. | A key assumption in the homogeneous variance model; its prior must be specified carefully [13]. |

| TC-G 1005 | TC-G 1005, MF:C25H25N3O2, MW:399.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| TC-I 2014 | TC-I 2014, MF:C23H19F6N3O, MW:467.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model in network meta-analysis?

The Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model is a statistical framework developed to assess inconsistency (also called incoherence) in network meta-analysis (NMA). Inconsistency occurs when direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (estimated through a common comparator) about treatment effects are in disagreement. This model provides a global test for inconsistency across the entire network of evidence by introducing interaction terms between the study design (the set of treatments being compared) and the treatment effects. When these interaction terms are statistically significant, it indicates the presence of inconsistency that threatens the validity of the NMA results [19] [20].

2. When should I use this model instead of other inconsistency assessment methods?

You should use the Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model when you need a comprehensive, global assessment of inconsistency in a network that may include multi-arm trials (trials with three or more treatment arms). Unlike simpler methods like the Bucher method, which only assesses inconsistency in simple three-treatment loops, this model can handle complex networks with various designs. It is considered one of the best methods for this purpose, particularly because it successfully addresses complications that arise from the presence of multi-arm trials [19] [20] [2].

3. What are the key limitations of this model I should be aware of?

Recent simulation studies have highlighted important limitations. The model can suffer from a high Type I error (approximately 0.4 to 0.45 in some scenarios), meaning it may incorrectly detect inconsistency when none exists. It may also lack sufficient statistical power (ranging from approximately 0.5 to 0.75 depending on the scenario) to reliably detect true inconsistency in a network. The power and error rates are heavily influenced by the assumed inconsistency factor in the data. These limitations suggest that while the model is valuable, its results should be interpreted cautiously, and further methodological work is needed to improve inconsistency assessment [20].

4. What software tools can I use to implement this model?

Several software options are available. The nmaINLA R package implements the model using Integrated Nested Laplace Approximations for Bayesian inference, providing a fast alternative to Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. The newly developed NMA R package offers a frequentist implementation with a user-friendly interface, incorporating functions for this model alongside other inconsistency assessment tools. Additionally, Stata's network package provides implementation within the multivariate meta-regression framework [21] [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Fails to Converge or Produces Errors

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Data: The model requires adequate direct evidence for each treatment comparison. Networks with sparse direct evidence or many treatments but few studies are problematic.

- Complexity: For highly connected networks with many treatments, the model becomes computationally demanding. Consider using alternative estimation methods like INLA [21].

- Implementation: Ensure you are using appropriate software. The

NMApackage in R is designed to handle the multivariate meta-regression framework required for this model and provides helpful error messages [22].

Problem: Model Detects Inconsistency but I Can't Identify the Source

Investigation Steps:

- Supplement with Local Methods: Use node-splitting methods to examine inconsistency for each treatment comparison individually. This helps pinpoint which direct comparisons conflict with the indirect evidence [2].

- Check for Effect Modifiers: Conduct network meta-regression by incorporating trial-level covariates (e.g., patient characteristics, risk of bias) into the model. These covariates might explain the observed inconsistency [19] [21].

- Evaluate Network Geometry: Use network graphs to visually identify poorly connected treatments or unusual patterns in the evidence structure that might contribute to inconsistency [23].

Problem: Interpreting the Random-Effects vs. Fixed-Effects Formulation

Decision Guidance:

- Random-Inconsistency Effects: This approach, as proposed by Jackson et al., models inconsistency parameters as following a common distribution. It is particularly useful for ranking treatments under inconsistency and for sensitivity analyses, as it involves fewer parameters. It facilitates the estimation of average treatment effects across all designs [19] [24].

- Fixed-Inconsistency Effects: This approach treats each inconsistency parameter as a separate, unrelated fixed effect. Higgins et al. argue this is more plausible when each inconsistency parameter has its own unique interpretation. A key practical advantage is that the resulting model can be fitted as a multivariate meta-regression [19].

- Recommendation: The random-effects formulation is often preferred for treatment ranking and when modeling inconsistency as an additional source of variation, similar to how between-study heterogeneity is handled in conventional meta-analysis [19].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Statistical Performance of the Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model

| Performance Metric | Reported Value/Range | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Type I Error | 0.4 to 0.45 [20] | Inconsistency factor, number of studies |

| Statistical Power | 0.5 to 0.75 [20] | True odds ratio, inconsistency factor, number of studies per comparison |

| Model Framework | Random-effects inconsistency model [19] [24] | Assumes inconsistency parameters follow a common distribution |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Function in Analysis | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Meta-regression Framework | Provides the statistical foundation for implementing the model and estimating parameters. | White et al. framework [22] |

R NMA Package |

A comprehensive R package for frequentist NMA, includes functions for the Design-by-Treatment model, inconsistency assessment, and graphical tools. | setup() function for data preparation [22] |

| INLA Estimation Method | A Bayesian computational method for latent Gaussian models; offers a faster alternative to MCMC for model fitting. | nmaINLA R package [21] |

| Global Inconsistency Test (Higgins) | A specific statistical test within the multivariate framework to check for the presence of global inconsistency in the network. | Available in the NMA package [22] |

Methodological Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points involved in implementing and interpreting the Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model for assessing inconsistency in a network meta-analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Parameterization Ambiguities in Node-Splitting

Problem: Different parameterizations of node-splitting models yield conflicting results when multi-arm trials are present in the network.

Explanation: Inconsistent outcomes occur because multi-arm trials contribute to multiple treatment comparisons simultaneously. When splitting a node (treatment comparison), the model must decide how to handle the dependencies within multi-arm trials. Three parameterization approaches exist, each making different assumptions about which treatment contributes to the inconsistency [14].

Solution:

- Identify the nature of your multi-arm trials: Determine how many multi-arm trials contribute to the comparison you are splitting.

- Select the appropriate parameterization method:

- Symmetrical method: Use when both treatments in the contrast may contribute to inconsistency.

- Single-treatment method: Use when only one specific treatment is suspected as the inconsistency source.

- Alternative single-treatment method: Use when the other treatment is suspected.

- Run analyses using all three parameterizations if the source of inconsistency is unknown, and compare results to understand the sensitivity of your findings.

Guide 2: Handling Inconsistency Detection in Complex Networks

Problem: Standard inconsistency detection methods fail or provide ambiguous results in networks with multi-arm trials.

Explanation: Traditional loop inconsistency approaches assume all trials are two-arm, but real-world networks often include multi-arm trials. Loop inconsistency cannot be defined unambiguously when multi-arm trials are present because inconsistency cannot occur within a multi-arm trial [1]. This complicates the detection and interpretation of inconsistency.

Solution:

- Use the design-by-treatment interaction model as a comprehensive approach that handles multi-arm trials naturally [1].

- Implement automated node-splitting with a decision rule that selects only comparisons in potentially inconsistent loops and ensures all potentially inconsistent loops are investigated [13].

- Validate findings with multiple inconsistency detection methods, noting that some methods like the net heat plot may not reliably signal inconsistency in all scenarios [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental concept behind node-splitting models in network meta-analysis?

Node-splitting is a method to evaluate inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence in network meta-analysis. It works by separating the evidence for a specific treatment comparison into two parts: (1) direct evidence from studies that directly compare the two treatments, and (2) indirect evidence from the remainder of the network. The method then assesses whether these two sources provide statistically different estimates of the treatment effect, which would indicate inconsistency in the network [13].

FAQ 2: Why do multi-arm trials present special challenges for evidence-splitting models?

Multi-arm trials present challenges because they contribute to multiple treatment comparisons simultaneously, creating complex dependencies in the evidence network. This leads to three specific issues:

- Parameterization ambiguity: There may be several valid node-splitting models for the same comparison when multi-arm trials are involved [13].

- Unclear inconsistency definition: Loop inconsistency cannot be defined unambiguously when multi-arm trials are present in the network [1].

- Different results from different parameterizations: Assigning the inconsistency parameter to one treatment versus another, or splitting it symmetrically, can yield different results [14].

FAQ 3: What are the different parameterization options for node-splitting models with multi-arm trials, and how do I choose?

Three parameterizations are available, each with different assumptions [14]:

| Parameterization | Assumption | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Symmetrical | Both treatments contribute equally to inconsistency | When no prior information about inconsistency source |

| Single-Treatment A | Only treatment A contributes to inconsistency | When theory suggests one specific treatment is problematic |

| Single-Treatment B | Only treatment B contributes to inconsistency | When theory suggests the other treatment is problematic |

FAQ 4: How can I implement automated node-splitting in my network meta-analysis?

Automated node-splitting requires:

- A decision rule to select which comparisons to split that investigates all potentially inconsistent loops [13].

- Accounting for multi-arm trials in the parameterization to ensure valid models [13].

- Software implementation that can handle the complex model generation, such as the methods described by van Valkenhoef et al. that build on automated model generation for network meta-analysis [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Node-Splitting Analysis for Multi-Arm Trial Networks

Purpose: To detect and evaluate inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence in a network meta-analysis containing multi-arm trials.

Methodology:

- Network Setup: Map all treatment comparisons, identifying multi-arm trials and potential loops where inconsistency may occur.

- Comparison Selection: Apply decision rules to select comparisons for splitting that cover all potentially inconsistent loops [13].

- Model Specification: For each selected comparison, specify three separate node-splitting models using the different parameterizations (symmetrical and two single-treatment approaches) [14].

- Model Estimation: Fit all models using Bayesian methods with appropriate priors and convergence diagnostics.

- Inconsistency Assessment: Compare direct and indirect estimates for each split node, evaluating statistical significance of differences.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Compare results across different parameterizations to assess robustness of findings.

Interpretation: Significant differences between direct and indirect evidence for any split node indicates local inconsistency in the network. Consistent results across parameterizations strengthen evidence for presence or absence of inconsistency.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Inconsistency Detection Methods for Network Meta-Analysis

| Method | Handling of Multi-Arm Trials | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node-Splitting [13] | Requires special parameterization | Straightforward interpretation of local inconsistencies | Labour-intensive without automation |

| Design-by-Treatment Interaction [1] | Handles naturally through design concept | Unambiguous model specification | Harder conceptual interpretation |

| Loop Inconsistency Approach [2] | Problematic with multi-arm trials | Simple implementation for two-arm trials | Cannot be defined unambiguously with multi-arm trials |

| Net Heat Plot [2] | Not clearly specified | Graphical presentation | Does not reliably signal inconsistency |

Methodological Visualization

Node-Splitting Conceptual Workflow

Multi-Arm Trial Complexity in Network Meta-Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Evidence-Splitting Models

| Item | Function | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Modeling Software | Estimate node-splitting models | Supports random-effects models and complex variance-covariance structures [13] |

| Automated Model Generation | Implement decision rules for comparison selection | Applies unambiguous decision rules for splitting comparisons [13] |

| Heterogeneity Assessment | Evaluate between-study variability | Calculates homogeneous-variance random-effects models [13] |

| Consistency Evaluation | Check agreement between direct and indirect evidence | Implements statistical tests for difference between evidence sources [13] [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a Net Heat plot and what does it visualize? A Net Heat plot is a graphical matrix tool used to locate and identify inconsistency within a network meta-analysis. It displays the contribution of direct evidence from specific designs (treatment comparisons) to network estimates and highlights "hot spots" of inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence [2] [25].

2. What do the colors in a Net Heat plot represent? In the matrix, the colors indicate the change in inconsistency when the consistency assumption is relaxed for a single design. Warm colors (e.g., red, orange) signify a decrease in inconsistency, while cool colors (e.g., blue) signify an increase. The intensity of the color corresponds to the magnitude of this change. The gray squares show the contribution of a direct estimate to a network estimate [25].

3. My Net Heat plot is empty or missing designs. Why does this happen? This is expected behavior for certain designs. The plot automatically excludes designs where only one treatment is involved in other parts of the network, or where removing the corresponding studies would cause the network to split into unconnected parts. These designs do not contribute to the inconsistency assessment and are therefore not shown [25].

4. How do I interpret a "hot spot" of inconsistency? A cluster of warm-colored cells (e.g., red) on the plot, particularly on the diagonal, indicates a design that is a potential source of inconsistency. If the colors in a column match the colors on the diagonal, detaching that specific design's effect may dissolve the total inconsistency in the network [25].

5. What are the main limitations of the Net Heat plot? The method has been criticized for potentially using an arbitrary weighting of direct and indirect evidence that can be misleading. Studies have shown that it may fail to reliably signal inconsistency or identify inconsistent designs, even when other statistical methods (like node-splitting or the Bucher method) suggest its presence [2].

6. What is the difference between a fixed-effect and random-effects Net Heat plot? The underlying statistical model can be changed. The plot can be based on a common (fixed) effects model or a random-effects model that incorporates between-study variance (τ²). The choice of model can affect the appearance and interpretation of the plot [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Difficulty Interpreting Net Heat Plot Colors and Values

Problem: The meaning of the colors (Q_diff) and gray squares in the plot is unclear, making interpretation challenging.

Solution: Interpret the plot elements systematically as outlined in the table below.

| Plot Element | Meaning | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Gray Square Area | Contribution of a direct estimate (column) to a network estimate (row). | A larger area signifies a greater contribution of that direct evidence to the overall network estimate [25]. |

| Diagonal Color | Inconsistency contribution of the corresponding design. | Warm colors here indicate that the design itself is a source of inconsistency [25]. |

| Off-Diagonal Color | Change in inconsistency for a row's estimate after detaching a column's design. | Cool (Blue): Increase in inconsistency. Warm (Red): Decrease in inconsistency [25]. |

Resolution Steps:

- Identify Clusters: Look for rows and columns with similar warm coloring, which are clustered by the algorithm to highlight inconsistency [25].

- Focus on the Diagonal: Check the diagonal for warm-colored cells to quickly identify designs that are primary drivers of inconsistency.

- Check Column Patterns: If a column's off-diagonal colors are identical to the diagonal, detaching that design may resolve the network's overall inconsistency [25].

Issue: Technical Implementation and Customization in R

Problem: Uncertainty about how to generate and customize the plot using the netmeta package in R.

Solution:

Use the netheat() function from the netmeta package. The R code snippet below shows a basic implementation and key parameters.

Parameters for Troubleshooting:

random: Set toTRUEto use a random-effects model instead of the default common effects model [25].tau.preset: Allows you to preset a value for the between-study variance τ² for the plot [25].showall: By default (FALSE), designs with minimal contribution to the inconsistency statistic are not shown. Set toTRUEto force them to appear [25].nchar.trts: Defines the minimum number of characters for creating unique treatment names, which can help with readability [25].

Issue: Low Contrast in Network Graph Visualization

Problem: A network graph has poor contrast, making it difficult to distinguish nodes and edges.

Solution: Manually define a high-contrast color for each node. This can be done by creating a color map. The following pseudocode and diagram illustrate the logic of assigning colors to maximize contrast between connected nodes.

Diagram 1: Logic for assigning high-contrast colors to network nodes.

Resolution Steps:

- Create a Color Map: Define a list to store the color for each node [26].

- Iterate and Assign: For each node in the graph, check the colors already assigned to its neighbors.

- Maximize Contrast: From your predefined palette, select a color that is most distinct from the neighbors' colors [27].

- Apply the Map: Pass the finalized color map to your graphing function's

node_colorparameter [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational tools and statistical packages for creating Net Heat and Net Path plots.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | The primary software environment for performing statistical computing and generating NMA visualizations. |

netmeta R Package |

A comprehensive frequentist package for network meta-analysis. It contains the netheat() function to create Net Heat plots [25]. |

| NetworkX (Python) | A Python library for creating and manipulating complex networks. While not for NMA-specific statistics, it is excellent for customizing network graph visuals, such as setting node colors for contrast [26] [28]. |

| Graphviz (DOT language) | A tool for representing graph structures. It is used here to create clear, high-contrast diagrams of workflows and network relationships. |

Comparative Analysis of Inconsistency Detection Methods

The table below summarizes key methods for detecting inconsistency in NMA, providing context for where Net Heat plots fit in the researcher's toolkit [2].

| Method | Type of Assessment | Key Characteristics | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net Heat Plot | Local & Global | Graphical matrix; Identifies locations and potential drivers of inconsistency. | Heat matrix with colors indicating inconsistency change [2] [25]. |

| Cochran's Q Statistic | Global | Single test statistic; Quantifies heterogeneity/inconsistency across the whole network. | Q statistic and p-value [2]. |

| Loop Inconsistency Approach | Local | Assesses inconsistency in loops of three treatments; Suitable only for two-arm trials. | Difference between direct and indirect evidence for each loop [2]. |

| Node-Splitting | Local | Separates direct and indirect evidence for a specific comparison to test their disagreement. | p-value for the difference between direct and indirect evidence for each split node [2]. |

| Inconsistency Parameter approach | Global | A hierarchical model that includes inconsistency parameters in each loop where inconsistency could occur. | Model fit statistics and parameter estimates for inconsistency [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary software options for performing a Network Meta-Analysis, and how do I choose? There are three primary frameworks for NMA: frequentist implementations in R and Stata, and Bayesian platforms [29]. The choice depends on your statistical background and analysis needs. Bayesian frameworks are used in an estimated 60-70% of NMA studies and are often considered logically well-suited for handling indirect and multiple comparisons [29]. However, if setting prior probabilities is complex for your research question, a frequentist approach using Stata or R might be more accessible [29].