Comparative Drug Efficacy Research: Guidelines, Methods, and Real-World Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to comparative drug efficacy research for drug development professionals and researchers.

Comparative Drug Efficacy Research: Guidelines, Methods, and Real-World Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to comparative drug efficacy research for drug development professionals and researchers. It covers foundational concepts, advanced methodological approaches including adjusted indirect comparisons and mixed treatment comparisons, strategies for troubleshooting common challenges in trial design and implementation, and frameworks for validation and interpretation of results. The content synthesizes current best practices to support robust evidence generation for clinical and regulatory decision-making in the absence of direct head-to-head trials.

Understanding Comparative Efficacy: Foundations and Critical Concepts

In the realm of drug development, the terms "efficacy" and "effectiveness" represent critically distinct concepts that describe drug performance at different stages of the evidence generation continuum. Efficacy refers to the capacity of a therapeutic intervention to produce a beneficial result under ideally controlled conditions, such as those found in randomized clinical trials (RCTs). In contrast, effectiveness describes its performance in real-world clinical practice among heterogeneous patient populations under routine care conditions. This whitepaper delineates the methodological, population, and contextual distinctions between these concepts, supported by contemporary regulatory frameworks and empirical evidence. It further provides structured protocols for designing studies that generate complementary evidence on both constructs, thereby supporting robust comparative drug efficacy research and informed healthcare decision-making.

Drug development relies on a progressive evidence generation pathway, moving from highly controlled experimental settings to pragmatic real-world observation. This pathway begins with efficacy establishment in clinical trials, which are designed to determine whether an intervention works under ideal circumstances. These studies prioritize high internal validity by rigorously controlling variables through strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, protocol-mandated procedures, and randomization to minimize bias [1] [2].

Following regulatory approval, evidence generation shifts toward assessing effectiveness—how the intervention performs in routine clinical practice among diverse patient populations, with comorbid conditions, concurrent medications, and varying adherence patterns. These real-world studies prioritize external validity (generalizability) to inform clinical practice, health policy, and reimbursement decisions [1] [3].

The distinction is not merely academic; it has profound implications for patient care and resource allocation. Comparative drug efficacy research must account for this continuum to produce meaningful, translatable findings. Modern regulatory guidance, including the ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice guideline, now explicitly supports using real-world data and innovative trial designs to bridge this evidence gap [4] [5].

Conceptual Frameworks and Key Distinctions

Defining the Core Concepts

Efficacy: The measurable ability of a therapeutic intervention to produce the intended beneficial effect under ideal and controlled conditions, typically assessed in Phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The primary question efficacy seeks to answer is: "Can this intervention work under optimal circumstances?" [2]

Effectiveness: The extent to which an intervention produces a beneficial outcome when deployed in routine clinical practice for broad, heterogeneous patient populations. The central question for effectiveness is: "Does this intervention work in everyday practice?" [1] [2]

The Efficacy-Effectiveness Relationship Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship and evidence continuum between efficacy and effectiveness research:

Methodological Differences: A Comparative Analysis

The distinction between efficacy and effectiveness manifests concretely through divergent methodological approaches across key study dimensions. The table below systematically compares these methodological characteristics.

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of Efficacy vs. Effectiveness Studies

| Study Characteristic | Efficacy (Clinical Trials) | Effectiveness (Real-World Studies) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Establish causal effect under ideal conditions | Measure benefit in routine practice |

| Study Design | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Observational studies, pragmatic trials, registry analyses |

| Patient Population | Homogeneous; strict inclusion/exclusion criteria [2] | Heterogeneous; broad eligibility reflecting clinical practice [1] |

| Sample Size | Often limited by design and cost | Typically larger, population-based [1] |

| Intervention Conditions | Protocol-mandated, standardized, strictly enforced | Flexible, tailored to individual patient needs |

| Comparator | Placebo or active control | Routine care, multiple active comparators |

| Setting | Specialized research centers, academic institutions [2] | Diverse real-world settings (hospitals, clinics, community practices) |

| Data Collection | Prospective, structured for specific research purpose | Often retrospective, from medical records, claims databases, or registries |

| Outcome Measures | Clinical surrogate endpoints, primary efficacy endpoint | Patient-centered outcomes, composite endpoints, healthcare utilization |

| Follow-up Duration | Fixed, predetermined duration | Variable, often longer-term |

| Internal Validity | High (through randomization, blinding, protocol control) | Variable, requires rigorous methods to address confounding |

| External Validity | Limited (restrictive eligibility) | High (broadly representative populations) |

Case Study: Evidence from Fabry Disease and Multiple Myeloma

Fabry Disease Treatment Outcomes

A recent systematic literature review of Fabry disease treatments provides a compelling case study contrasting efficacy and effectiveness evidence [2]. The review analyzed 234 publications, with the majority (67%) being real-world observational studies, and the remainder (32%) clinical trials.

Efficacy Evidence from Clinical Trials: Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with agalsidase alfa or beta demonstrated stabilization of renal function and cardiac structure in controlled trial settings. These trials established that early initiation of ERT in childhood or young adulthood was associated with better renal and cardiac outcomes compared to later initiation [2].

Effectiveness Evidence from Real-World Studies: The large number of observational studies provided complementary evidence on treatment performance in heterogeneous patient populations over extended periods. These studies confirmed that treatment effects observed in trials generally translated to real-world practice, but also provided insights into long-term outcomes, safety profiles, and comparative effectiveness across different patient subgroups that were not represented in the original trials [2].

The Fabry disease case highlights a critical challenge in comparative efficacy research: the high heterogeneity of study designs and patient populations in real-world evidence, which often precludes direct cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses [2].

Multiple Myeloma Treatment Patterns

A population-based study specifically designed to compare clinical trial efficacy versus real-world effectiveness in multiple myeloma treatments further illustrates this dichotomy [1] [3]. Such comparative studies are essential for understanding whether efficacy benchmarks established in trials are translated into clinical practice, particularly for complex therapeutic regimens that may be challenging to implement outside research settings.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Approaches

Clinical Trial Protocol Design (Efficacy Assessment)

The SPIRIT 2025 statement provides updated guidelines for clinical trial protocols, emphasizing comprehensive reporting to enhance study quality and transparency [6]. The following workflow outlines the core components of efficacy-oriented trial design:

Detailed Protocol Components [6]:

- Structured Summary: Comprehensive trial design overview following WHO Trial Registration Data Set

- Patient Population: Strict eligibility criteria to create homogeneous study cohort

- Intervention Protocol: Precise description of treatment regimen, dosage, administration schedule

- Comparator Selection: Placebo or active control with randomization procedures

- Primary Endpoint: Clinically relevant efficacy measure with specified assessment timeline

- Sample Size Justification: Statistical power calculation based on expected effect size

- Data Collection Methods: Standardized case report forms with rigorous quality control

- Statistical Analysis Plan: Pre-specified analysis methods, including handling of missing data

Real-World Evidence Generation Protocol (Effectiveness Assessment)

For real-world effectiveness studies, the methodological approach must address different challenges, particularly confounding and data quality issues:

Table 2: Real-World Evidence Generation Protocol

| Protocol Component | Methodological Approach | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source Selection | Electronic health records, claims databases, disease registries | Assess completeness, accuracy, and representativeness of data |

| Study Population | Broad inclusion criteria reflecting clinical practice | Define eligibility based on treatment patterns rather than strict criteria |

| Exposure Definition | Treatment patterns based on actual prescriptions/administration | Account for treatment switching, discontinuation, and adherence |

| Comparator Group | Active treatment comparison using propensity score methods | Address channeling bias and unmeasured confounding |

| Outcome Measurement | Clinical events, patient-reported outcomes, healthcare utilization | Validate outcome definitions in specific data source |

| Follow-up Period | From treatment initiation to outcome, discontinuation, or end of study | Account for variable follow-up and informative censoring |

| Confounding Control | Multivariable adjustment, propensity scores, instrumental variables | Conduct sensitivity analyses to assess robustness |

| Statistical Analysis | Time-to-event analysis, marginal structural models | Account for time-varying confounding and competing risks |

Regulatory and Methodological Evolution

Modernizing Clinical Trial Frameworks

Recent regulatory updates reflect the growing importance of bridging the efficacy-effectiveness gap:

ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice: The updated guideline introduces "flexible, risk-based approaches" and embraces "modern innovations in trial design, conduct, and technology" [4] [5]. It specifically addresses non-traditional interventional trials and those incorporating real-world data sources, facilitating more pragmatic designs that can generate both efficacy and effectiveness evidence [5].

SPIRIT 2025 Statement: The updated guideline for clinical trial protocols now includes items on patient and public involvement in trial design, conduct, and reporting, enhancing the relevance of trial outcomes to real-world stakeholders [6].

Estimand Framework Implementation

The adoption of ICH E9(R1) on estimands represents a significant methodological advancement for aligning efficacy and effectiveness assessment [4]. The estimand framework clarifies how intercurrent events (e.g., treatment switching, discontinuation) are handled in the definition of treatment effects, creating a more transparent link between the clinical question of interest and the statistical analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Comparative Efficacy-Effectiveness Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SPIRIT 2025 Checklist | 34-item checklist for comprehensive trial protocol design [6] | Ensuring methodological rigor and transparency in efficacy studies |

| ICH E6(R3) GCP Guideline | Framework for ethical, quality clinical trial conduct [4] [5] | Implementing risk-based approaches across traditional and innovative trials |

| Estimand Framework (ICH E9(R1)) | Structured definition of treatment effects addressing intercurrent events [4] | Aligning statistical estimation with clinical questions in both RCTs and RWE |

| PRISMA Guidelines | Systematic review and meta-analysis reporting standards [2] | Synthesizing evidence across efficacy and effectiveness studies |

| ROBINS-I Tool | Risk of bias assessment for non-randomized studies [2] | Critical appraisal of real-world effectiveness studies |

| Multi-Touch Attribution Models | Distributing conversion credit across customer journey touchpoints [7] | Analogous to understanding multiple contributors to treatment response |

| Real-World Data Quality Frameworks | Assessing fitness-for-use of EHR, claims, registry data | Ensuring reliability of data sources for effectiveness research |

| Pragmatic Trial Design Templates | Protocols balancing internal and external validity [6] | Generating evidence applicable to routine care settings |

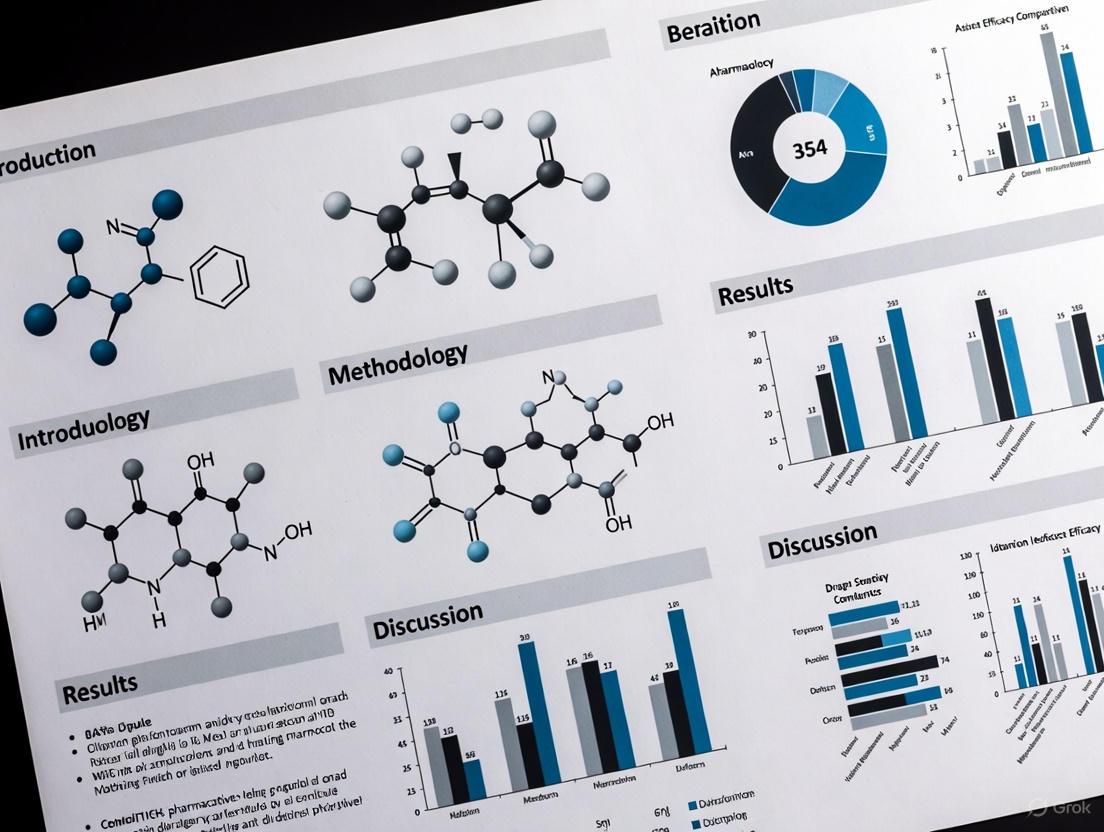

| Hydroprotopine | Hydroprotopine, MF:C20H20NO5+, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Spiraeoside | Spiraeoside, CAS:20229-56-5, MF:C21H20O12, MW:464.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The distinction between efficacy and effectiveness remains fundamental to evidence-based medicine and drug development. Efficacy establishes the foundational proof of concept under ideal conditions, while effectiveness demonstrates real-world value in routine practice. Rather than viewing these as competing paradigms, contemporary drug development should embrace integrated evidence generation that strategically combines both approaches.

The evolving regulatory landscape, exemplified by ICH E6(R3) and SPIRIT 2025, supports this integration through more flexible, pragmatic approaches to clinical research [6] [5]. For comparative drug efficacy research to meaningfully inform clinical practice and health policy, it must account for both the internal validity of efficacy studies and the external validity of effectiveness research. This requires methodological rigor in both randomized and observational settings, transparent reporting of study limitations, and appropriate interpretation of findings within each context's constraints.

Future advances in real-world data quality, causal inference methods, and pragmatic trial design will further enhance our ability to bridge the efficacy-effectiveness gap, ultimately accelerating the delivery of beneficial treatments to the diverse patient populations who need them.

The Critical Need for Comparative Data in Clinical and Health Policy Decision-Making

The landscape of clinical care is marked by wide variations in treatments, outcomes, and costs, resulting in significant disparities in both the quality and cost of healthcare [8]. Despite healthcare expenditures in the United States exceeding those of other countries, relatively unfavorable health outcomes persist [8]. This environment has fueled demands from healthcare decisionmakers for more evidence of the comparative effectiveness and cost effectiveness of medical interventions [8]. Comparative effectiveness research (CER) serves as a critical mechanism to fill current knowledge gaps in healthcare decisionmaking by generating and synthesizing evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor clinical conditions or to improve the delivery of care [8]. The fundamental purpose of CER is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers in making informed decisions that improve healthcare at both individual and population levels [8].

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) emphasizes that CER must directly compare alternative interventions, study patients in real-world clinical settings, and strive to tailor medical decisions to individual patient or subgroup values and preferences [8]. This approach represents a significant evolution beyond traditional efficacy studies conducted under ideal conditions, instead focusing on effectiveness in routine practice settings where patient populations are more diverse and comorbidities are common.

Methodological Frameworks for Comparative Research

Core Study Designs in Comparative Effectiveness Research

CER employs a range of methodological approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The principal methods include observational studies (both prospective and retrospective), randomized trials, decision analysis, and systematic reviews [8]. Well-designed, methodologically rigorous observational studies and randomized trials conducted in real-world settings have the potential to improve the quality, generalizability, and transferability of study findings [8].

Table 1: Key Methodological Approaches in Comparative Effectiveness Research

| Study Design | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Pragmatic Trials | Conducted in real-world settings; may have broader inclusion criteria | High internal validity; minimizes confounding | Can be costly and time-consuming; may have limited generalizability |

| Prospective Observational Studies | Participants identified before outcome occurrence; follows participants over time | Includes diverse patients from routine practice; strengthens external generalizability | Vulnerable to confounding and bias; requires careful statistical adjustment |

| Retrospective Observational Studies | Uses existing data collected for other purposes | Quickly provides low-cost, large study populations; efficient for long-term outcomes | Limited control over data quality; potential for unmeasured confounding |

| Network Meta-Analysis | Simultaneously compares multiple interventions using direct and indirect evidence | Facilitates comparison of interventions not directly studied in head-to-head trials | Requires careful assessment of transitivity and consistency assumptions |

The advantage of observational studies is their ability to quickly provide low-cost, large study populations drawn from diverse patients obtained during routine clinical practice, thereby strengthening the external generalizability of study findings [8]. However, these studies are limited by inherent bias and confounding that routinely occur in nonrandomized studies [8]. To minimize threats to internal validity, research guidelines recommend a priori specification of research questions, targeted patient populations, comparative interventions, and postulated confounders; selection of appropriate study designs; careful data source selection; and transparency in protocol development and prespecified analytic plans [8].

Methodological Standards and Analytical Considerations

To ensure the validity of CER findings, several methodological standards must be maintained. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Good Research Practices Task Force provides detailed recommendations on determining when to conduct prospective versus retrospective studies, the advantages and disadvantages of different study designs, and analytic approaches to consider in study execution [8]. Advanced statistical methods including regression analysis, propensity scores, sensitivity analysis, instrumental variables, and structural model equations are essential for addressing confounding in observational studies [8].

For retrospective observational studies leveraging existing data sources, applications are expected to compare existing interventions that represent a current decisional dilemma and have robust evidence of efficacy or are currently in widespread use [9]. These studies permit the observation of long-term impacts and unintended adverse events over periods longer than typically feasible in clinical trials [9]. Methods that represent state-of-the-art causal inference approaches for retrospective observational designs and utilize data from multiple health systems or multiple sites within large integrated health systems are strongly encouraged to facilitate generalizable CER results [9].

Data Presentation Standards for Comparative Research

Effective Tabulation of Quantitative Data

The presentation of quantitative data in comparative effectiveness research requires careful consideration to ensure clear communication of findings. Tabulation represents the first step before data is used for analysis or interpretation [10]. Effective tables should be numbered, contain a brief and self-explanatory title, and have clear and concise headings for columns and rows [10]. Data should be presented logically—by size, importance, chronological order, alphabetical order, or geographical distribution [10]. When percentages or averages are compared, they should be placed as close as possible, and tables should not be excessively large [10]. Vertical arrangements are generally preferable to horizontal layouts because scanning data from top to bottom is easier than from left to right [10].

For quantitative variables, data should be divided into class intervals with frequencies noted against each interval [10]. The class intervals should be equal in size throughout the distribution [10]. The number of groups or classes should be optimal—customarily between 6-16 classes—with headings that clearly mention units of data (e.g., percent, per thousand, mmHg) [10]. Groups should be presented in ascending or descending order, and the table should be numbered with a clear, concise, self-explanatory title [10].

Table 2: Data Presentation Formats for Different Variable Types

| Variable Type | Recommended Tables | Recommended Graphs/Charts | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical Variables | Frequency distribution tables with absolute and relative frequencies | Bar charts, Pareto charts, pie charts | Include total number of observations; use appropriate legends for category identification |

| Numerical Variables | Frequency distribution with class intervals of equal size | Histograms, frequency polygons, frequency curves | Class intervals should be equal throughout; optimal number of intervals is 6-16 |

| Time-Based Data | Time series tables with consistent intervals | Line diagrams, frequency polygons | Time intervals should be consistent (month, year, decade) to depict trends accurately |

| Comparative Data | Contingency tables, multiple group comparisons | Comparative histograms, bar charts, frequency polygons | Place comparison groups adjacent to facilitate visual comparison |

Graphical Representation of Comparative Data

Graphical presentations provide striking visual impact and help convey the essence of statistical data, circumventing the need for extensive detail [10]. However, these visualizations must be produced correctly using appropriate scales to avoid distortion and misleading representations [10]. All graphs, charts, and diagrams should be self-explanatory, with informative titles and clearly labeled axes [10].

For quantitative data, histograms provide a pictorial diagram of frequency distribution, consisting of a series of rectangular and contiguous blocks where the area of each column depicts the frequency [10]. Frequency polygons are obtained by joining the mid-points of histogram blocks and are particularly useful when comparing distributions of different sets of quantitative data [10]. When numerous observations are available and histograms are constructed using reduced class intervals, the frequency polygon becomes less angular and more smooth, forming a frequency curve [10]. For comparing two groups, comparative histograms or bar charts with groups placed next to each other are effective, as are frequency polygons with multiple lines representing different groups [10].

Implementation Framework and Stakeholder Engagement

Patient and Stakeholder Engagement in CER

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has formally incorporated the concept of "patient-centeredness" into CER, characterizing patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) by: (1) comparing alternative approaches to clinical management; (2) actively engaging patients and key stakeholders throughout the research process; (3) assessing outcomes meaningful to patients; and (4) implementing research findings in clinical settings [8]. Engaging stakeholders in research improves the relevance of study questions, increases transparency, enhances study implementation, and accelerates the adoption of research findings into practice and health policy [8].

Stakeholders in CER are categorized into seven groups: patients and the public, providers (individuals or organizations), purchasers (responsible for underwriting costs of care), payers (responsible for reimbursement), policy makers, product makers (drug/device manufacturers), and principal investigators (researchers or their funders) [8]. Research indicates that patients are the most frequently engaged stakeholder group, with engagement most often occurring in the early stages of research (prioritization) [8]. Engagement strategies range from surveys, focus groups, and interviews to participation in study advisory boards or research teams [8].

PCORI's Patient and Family Engagement Rubric outlines stakeholder engagement throughout study planning, study implementation, and dissemination of results [8]. The rubric describes four key engagement principles: (1) reciprocal relationships with clearly outlined roles of all research partners; (2) colearning as a bidirectional process; (3) partnership with fair financial compensation and accommodation for cultural diversity; and (4) trust, transparency, and honesty through inclusive decisionmaking and shared information [8].

Infrastructure and Policy Support

Learning health systems and practice-based research networks provide the infrastructure for advancing CER methods, generating local solutions to high-quality cost-effective care, and transitioning research into implementation and dissemination science [8]. The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) established the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) as a government-sponsored nonprofit organization to advance the quality and relevance of clinical evidence that patients, clinicians, health insurers, and policy makers can use to make informed decisions [8]. PCORI's funding comes from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund, which receives funding from the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund, the Treasury general fund, and fees on health plans to support CER [8].

The PPACA defines CER as "research evaluation and comparing health outcomes and clinical effectiveness, risks, and benefits of two or more medical treatments, services, and items" [8]. The law further specifies that PCORI must ensure that CER accounts for differences in key subpopulations (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, age, and comorbidity) to increase the relevance of the research [8]. This legislative framework has moved the United States toward a national policy for CER to increase accountability for quality and cost of care [8].

Case Example: ADHD Medication Comparative Research

Experimental Protocol and Methodological Approach

A comprehensive network meta-analysis of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) demonstrates the application of CER methodologies to inform clinical decision-making [11]. The study aimed to estimate the comparative efficacy and tolerability of oral medications for ADHD across children, adolescents, and adults through a systematic review and network meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials [11].

Literature Search Strategy: Researchers searched multiple databases (PubMed, BIOSIS Previews, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, OpenGrey, Web of Science Core Collection, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and WHO International Trials Registry Platform) from inception up to April 7, 2017, without language restrictions [11]. Search terms included "adhd" OR "hkd" OR "addh" OR "hyperkine" OR "attention deficit" combined with a list of ADHD medications [11].

Study Selection and Data Extraction: The analysis included 133 double-blind randomized controlled trials (81 in children and adolescents, 51 in adults, and one in both) [11]. Researchers systematically contacted study authors and drug manufacturers for additional information, including unpublished data [11]. This comprehensive approach minimized publication bias and enhanced the robustness of findings.

Outcome Measures and Analysis: Primary outcomes were efficacy (change in severity of ADHD core symptoms based on teachers' and clinicians' ratings) and tolerability (proportion of patients who dropped out of studies because of side-effects) at timepoints closest to 12 weeks, 26 weeks, and 52 weeks [11]. Researchers estimated summary odds ratios (ORs) and standardized mean differences (SMDs) using pairwise and network meta-analysis with random effects, assessing risk of bias with the Cochrane risk of bias tool and confidence of estimates with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach for network meta-analyses [11].

Key Findings and Clinical Implications

The analysis of efficacy closest to 12 weeks was based on 10,068 children and adolescents and 8,131 adults, while the analysis of tolerability was based on 11,018 children and adolescents and 5,362 adults [11]. For ADHD core symptoms rated by clinicians in children and adolescents closest to 12 weeks, all included drugs were superior to placebo [11]. In adults, amphetamines, methylphenidate, bupropion, and atomoxetine, but not modafinil, were better than placebo based on clinicians' ratings [11].

With respect to tolerability, amphetamines were inferior to placebo in both children and adolescents (OR 2.30) and adults (OR 3.26), while guanfacine was inferior to placebo in children and adolescents only (OR 2.64) [11]. In head-to-head comparisons, differences in efficacy were found favoring amphetamines over modafinil, atomoxetine, and methylphenidate in both children and adolescents (SMDs -0.46 to -0.24) and adults (SMDs -0.94 to -0.29) [11].

Table 3: Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of ADHD Medications

| Medication | Efficacy in Children/Adolescents (SMD vs. placebo) | Efficacy in Adults (SMD vs. placebo) | Tolerability in Children/Adolescents (OR vs. placebo) | Tolerability in Adults (OR vs. placebo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamines | -1.02 (-1.19 to -0.85) | -0.79 (-0.99 to -0.58) | 2.30 (1.36-3.89) | 3.26 (1.54-6.92) |

| Methylphenidate | -0.78 (-0.93 to -0.62) | -0.49 (-0.64 to -0.35) | Not significant | 2.39 (1.40-4.08) |

| Atomoxetine | -0.56 (-0.66 to -0.45) | -0.45 (-0.58 to -0.32) | Not significant | 2.33 (1.28-4.25) |

| Bupropion | Insufficient data | -0.46 (-0.85 to -0.07) | Insufficient data | Insufficient data |

| Modafinil | -0.76 (-1.15 to -0.37) | 0.16 (-0.28 to 0.59) | Not significant | 4.01 (1.42-11.33) |

| Guanfacine | -0.67 (-1.01 to -0.32) | Insufficient data | 2.64 (1.20-5.81) | Insufficient data |

The study concluded that, taking into account both efficacy and safety, evidence supports methylphenidate in children and adolescents and amphetamines in adults as preferred first-choice medications for the short-term treatment of ADHD [11]. This comprehensive network meta-analysis informs patients, families, clinicians, guideline developers, and policymakers on the choice of ADHD medications across age groups, demonstrating the critical role of comparative data in clinical decision-making [11].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Effectiveness Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Existing Data Networks (e.g., PCORnet) | Provides infrastructure for large-scale observational studies using real-world data | Ensures representative populations; facilitates generalizable results; requires demonstrated data access at time of application [9] |

| Standardized Outcome Measures | Assesses clinically meaningful endpoints important to patients | Should include both clinical and patient-centered outcomes; must be validated and justified in study protocol [9] |

| Causal Inference Methodologies | Addresses confounding in observational studies through advanced statistical approaches | Includes propensity scores, instrumental variables, sensitivity analyses; represents state-of-the-art analytical techniques [8] [9] |

| Stakeholder Engagement Frameworks | Ensures research relevance and accelerates translation into practice | Incorporates patients, clinicians, payers, policymakers; follows established principles for reciprocal relationships and colearning [8] |

| Network Meta-Analysis Software | Simultaneously compares multiple interventions using direct and indirect evidence | Requires careful assessment of transitivity and consistency assumptions; uses random effects models for summary estimates [11] |

The critical need for comparative data in clinical and health policy decision-making continues to drive methodological innovations in comparative effectiveness research. Well-designed CER that incorporates rigorous methodologies, comprehensive data presentation, and meaningful stakeholder engagement provides an essential foundation for informed healthcare decisions. The ADHD medication network meta-analysis exemplifies how sophisticated comparative research methodologies can generate evidence that directly informs clinical practice across different patient populations [11].

Future directions for CER include addressing the paucity of long-term comparative outcomes beyond 12 weeks, incorporating individual patient data in network meta-analyses to better predict individual treatment response, and leveraging established data sources for efficient retrospective studies that complement randomized controlled trials [11] [9]. As CER methodologies continue to evolve, their integration into learning health systems will be essential for generating local solutions to high-quality cost-effective care and transitioning research into implementation and dissemination science [8]. This progressive approach to evidence generation will ultimately guide health policy on clinical care, payment for care, and population health, fulfilling the promise of comparative effectiveness research to improve healthcare decision-making at both individual and population levels.

In the rigorous field of comparative drug efficacy research, the hierarchy of evidence serves as a critical framework for evaluating the validity and reliability of clinical study findings. This structured approach systematically ranks research methodologies based on their ability to minimize bias, establish causal relationships, and generate clinically applicable results. At the foundation of evidence-based medicine (EBM), this hierarchy provides essential guidance for researchers, regulators, and clinicians navigating the complex landscape of therapeutic development [12]. The evidence pyramid graphically represents this ranking structure, with systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the apex, followed by randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies (cohort and case-control designs), case series and reports, and finally expert opinions and anecdotal evidence at the base [12]. Understanding this hierarchy is fundamental for designing robust clinical development programs, interpreting research findings accurately, and making informed decisions about drug efficacy and safety.

The historical perspective of evidence hierarchy dates back to the mid-20th century, with British epidemiologist Archie Cochrane pioneering the emphasis on systematic reviews of RCTs. This foundational work paved the way for organizations such as the Cochrane Collaboration, which continues to advance EBM through rigorous methodology [12]. Seminal publications by Sackett et al. further popularized the evidence hierarchy, establishing it as an essential component of medical education and practice. These frameworks have continuously evolved to incorporate emerging evidence sources, including real-world data and novel analytical technologies, while maintaining core methodological principles that safeguard research integrity [12]. For drug development professionals, this hierarchical approach provides a systematic method for prioritizing high-quality evidence, critically evaluating research findings, and integrating scientific advances into therapeutic development and patient care, ultimately enhancing research quality and health outcomes.

The Evidence Pyramid: A Systematic Framework

Detailed Levels of Evidence

The evidence pyramid provides a structured representation of research methodologies, ranked according to their inherent ability to minimize bias and establish causal inference. Each level within this hierarchy offers distinct advantages and limitations that researchers must consider when designing studies or evaluating therapeutic efficacy [12].

Level I: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Occupying the highest position in the evidence hierarchy, systematic reviews and meta-analyses comprehensively synthesize data from multiple high-quality studies, typically RCTs. By systematically collecting and statistically analyzing results from numerous investigations, these studies provide the most definitive conclusions about therapeutic efficacy while minimizing bias through rigorous methodology. The quality of a systematic review is directly determined by the scientific rigor of the included studies, following the principle that "low-quality inputs produce subpar results" [12]. These comprehensive analyses form the foundation for clinical practice guidelines and healthcare policy decisions, offering the most reliable evidence for efficacy assessments.

Level II: Randomized Controlled Trials RCTs represent the gold standard for establishing causal relationships between interventions and outcomes in clinical research. Through random allocation of participants to intervention or control groups, this methodology effectively minimizes selection bias and controls for confounding variables. The rigorous design includes blinding techniques to reduce observer and participant bias, creating a controlled environment for precise efficacy assessment [12]. However, RCTs face significant challenges including ethical limitations, substantial resource requirements, inflexible protocols, and extended timelines. Furthermore, certain patient populations or interventions may be unsuitable for RCTs, creating evidence gaps that require alternative methodological approaches [12].

Level III: Cohort and Case-Control Studies As primary observational research designs, cohort and case-control studies provide valuable insights into treatment effects in real-world settings. Cohort studies track groups of participants over time to evaluate outcomes, while case-control studies compare individuals with and without a specific condition to identify potential causative factors [12]. Prospective cohort studies offer stronger causal inferences through continuous participant monitoring, ensuring reliable data collection while minimizing recall bias. Retrospective studies analyze historical data but are more susceptible to selection bias and information limitations. While these observational designs offer significant real-world applicability, they remain less reliable than RCTs due to potential confounding variables that cannot be fully controlled without randomization [12].

Level IV: Case Series and Case Reports These descriptive studies provide detailed information on individual patients or small groups, typically highlighting unusual disease presentations, innovative treatments, or rare adverse events. While valuable for hypothesis generation and identifying novel therapeutic avenues, these designs lack control groups and statistical power, severely limiting their generalizability [12]. Case series and reports primarily serve to guide future research directions rather than establish efficacy, providing preliminary observations that may inform more rigorous investigation through controlled studies.

Level V: Expert Opinion and Anecdotal Evidence Positioned at the base of the evidence hierarchy, expert opinions and anecdotal evidence rely on individual clinical experience and isolated observations rather than systematic investigation. While potentially insightful, particularly for rare conditions or novel interventions where robust evidence is lacking, these sources are inherently subjective and susceptible to significant bias [12]. Without standardization or controls, expert opinions represent the least reliable evidence for efficacy assessments, though they may provide valuable guidance when higher-level evidence is unavailable.

Table 1: Levels of Evidence in Medical Research

| Evidence Level | Study Design | Key Strengths | Major Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I (Highest) | Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses | Comprehensive synthesis, minimal bias, definitive conclusions | Quality dependent on included studies, time-consuming | Clinical guidelines, policy decisions, efficacy confirmation |

| Level II | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Gold standard for causality, minimizes selection bias, controls confounding | Resource-intensive, ethical constraints, limited generalizability | Pivotal efficacy trials, regulatory submissions |

| Level III | Cohort & Case-Control Studies | Real-world applicability, ethical feasibility, larger sample sizes | Potential confounding, selection bias, limited causal inference | Post-marketing surveillance, safety studies, comparative effectiveness |

| Level IV | Case Series & Reports | Hypothesis generation, identifies rare events, rapid dissemination | No control group, limited generalizability, susceptible to bias | Novel therapies, rare diseases, adverse event reporting |

| Level V (Lowest) | Expert Opinion & Anecdotal Evidence | Clinical insights, guides when evidence scarce | Subjective, no controls, significant bias potential | Preliminary guidance, rare conditions, methodological advice |

Visualizing the Evidence Hierarchy

Single-Arm Trials: Design, Applications, and Limitations

Methodological Framework and Characteristics

Single-arm trials (SATs) represent a specialized clinical design in which all enrolled participants receive the experimental intervention without concurrent control groups, with outcomes evaluated against historical benchmarks or predetermined efficacy thresholds [13]. This methodological approach eliminates randomization processes and control arms, instead utilizing comparable patient populations as reference standards through either pre-specified efficacy thresholds or external control comparisons [13]. The fundamental design characteristics of SATs include prospective follow-up of all participants receiving the identical investigational treatment, absence of randomization and control groups, and reliance on external historical data for outcome contextualization.

The operational advantages of SAT designs include simplified implementation, reduced resource requirements, shorter development timelines, and smaller sample sizes compared to randomized controlled trials. These practical benefits position SATs as an accelerated pathway for drug development and regulatory approval, particularly in specialized clinical contexts [13]. The ethical feasibility of SAT designs is especially relevant in serious or life-threatening conditions with no available therapeutic alternatives, where randomization to placebo or inferior standard care may be problematic. However, despite these operational advantages, the interpretation of SAT results presents significantly greater complexity than RCTs, requiring sophisticated analytical approaches and careful consideration of multiple assumptions that are inherently controlled for in randomized designs [13].

Challenges and Methodological Limitations

SATs face substantial methodological challenges that impact both the validity and reliability of their efficacy assessments. The fundamental absence of randomization creates intrinsic limitations in establishing definitive causal relationships between interventions and outcomes [13].

Compromised Internal Validity Without random allocation, SATs lack methodological safeguards against confounding from unmeasured prognostic determinants. This systematic inability to account for latent variables undermines the fundamental basis for ensuring internal validity in therapeutic effect estimation [13]. Unlike RCTs, where random allocation ensures approximate equipoise in both measured and latent prognostic factors across treatment arms, SATs cannot establish statistically robust frameworks for causal inference, leaving efficacy assessments vulnerable to multiple confounding influences.

Constrained External Validity The same methodological limitation (absence of concurrent controls) creates dual threats to external validity by precluding direct quantification of treatment effects [13]. Efficacy interpretation depends critically on two assumptions: (1) precise characterization of counterfactual outcomes (the hypothetical disease trajectory without the investigational treatment under identical temporal and diagnostic contexts), and (2) prognostic equipoise between study participants and external controls across both measured and latent biological determinants. Consequently, SAT-derived efficacy estimates exhibit inherent context-dependence, constrained to narrowly defined patient subgroups under protocol-specific conditions with limited generalizability beyond the trial's operational parameters [13].

Additional Methodological Concerns Statistical reliability represents another significant challenge for SATs. Efficacy estimates become particularly susceptible to sampling variability, especially in studies with limited sample sizes and/or high outcome variability [13]. The uncertainty inherent in estimating treatment efficacy from SATs warrants special consideration, as only variability within the experimental group is directly observable, while variability of hypothetical control groups remains unknown. Furthermore, when employing external controls—whether for threshold establishment or direct comparison—multiple bias sources can systematically impact validity estimates, including selection bias (differences in patient characteristics), temporal bias (changes in standard care over time), information bias (variations in outcome assessment), confounding bias (unmeasured prognostic factors), treatment-related bias (differences in concomitant therapies), and reporting bias (selective outcome reporting) [13].

Regulatory Context and Appropriate Applications

SATs find their primary application in specialized clinical contexts where randomized controlled trials may be impractical or unethical. These specific scenarios include orphan drug development for rare diseases with constrained patient recruitment pools, and oncology drugs targeting life-threatening conditions with no effective treatment alternatives [13]. In these situations, SATs may provide early efficacy evidence in urgent clinical contexts where conventional randomized designs are not feasible.

The regulatory landscape for SATs is evolving, with recent guidance reflecting increased methodological scrutiny. Historically, regulatory agencies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have accepted SATs as support for accelerated approval, particularly in oncology [14]. However, recent draft guidance issued in March 2023 emphasizes a preference for randomized trials over single-arm designs, representing a significant policy shift [14]. This guidance explains that RCTs provide more accurate efficacy and safety profiles, enabling robust benefit-risk assessments and potentially supporting both accelerated and traditional approval through a "one trial" approach [14].

While acknowledging that RCTs may not be feasible in certain circumstances (e.g., very rare tumors), the FDA still considers SATs for accelerated approval if they demonstrate significant effects on surrogate endpoints reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit [14]. The guidance specifically notes limitations regarding certain endpoints in SATs, stating that "common time-to-event efficacy endpoints in oncology in single-arm trials are generally uninterpretable due to failure to account for known and unknown confounding factors when comparing the results to an external control" [14]. This regulatory evolution underscores the importance of early regulatory communication for sponsors considering SAT designs, with recommendation to seek FDA feedback on trial designs before initiating enrollment [14].

Table 2: Single-Arm Trials: Applications and Methodological Challenges

| Aspect | Details | Implications for Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Applications | Rare diseases with limited patient populations, life-threatening conditions with no available therapies, initial efficacy evidence for accelerated pathways | Expedited development for urgent unmet medical needs, ethical feasibility when randomization problematic |

| Key Advantages | Faster implementation, reduced sample size, lower costs, ethical feasibility in serious conditions, accelerated regulatory pathways | Reduced development timelines and resources, particularly beneficial for small populations and serious conditions |

| Major Limitations | No concurrent controls, vulnerable to selection bias, temporal bias, confounding variables, limited causal inference | Efficacy estimates uncertain, regulatory scrutiny increasing, generalizability constrained |

| Recent Regulatory Trends | FDA preference for RCTs (March 2023 guidance), increased emphasis on randomized data, requirement for robust justification of SAT use | Shift toward randomized designs even in accelerated pathways, need for early regulatory consultation on trial design |

| Endpoint Considerations | Objective response rate (ORR) generally acceptable, time-to-event endpoints (PFS, OS) problematic in SATs | Endpoint selection critical for interpretability, avoidance of uninterpretable endpoints in single-arm context |

Randomized Controlled Trials: The Gold Standard

Methodological Rigor and Causal Inference

Randomized controlled trials represent the methodological cornerstone for establishing therapeutic efficacy, providing the most reliable evidence for causal relationships between interventions and clinical outcomes. The fundamental principle underlying RCTs—random allocation of participants to intervention groups—ensures that both known and unknown prognostic factors are distributed approximately equally across treatment arms, creating statistically comparable groups at baseline [12]. This methodological safeguard minimizes selection bias and controls for potential confounding variables, establishing a robust framework for attributing outcome differences to the investigational intervention rather than extraneous factors.

The RCT design incorporates additional methodological strengtheners including blinding procedures (masking of patients, investigators, and/or outcome assessors to treatment assignments), predefined statistical analysis plans, and prospective endpoint assessment [12]. These features collectively reduce multiple forms of bias that could otherwise compromise study validity. The controlled environment of RCTs enables precise specification of inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment protocols, and monitoring procedures, ensuring standardized implementation across study sites and enhancing internal validity [12]. For regulatory decision-making and clinical guideline development, RCTs provide the definitive evidence foundation, particularly when well-designed, adequately powered, and properly executed.

Practical Challenges and Implementation Considerations

Despite their methodological advantages, RCTs face significant practical challenges that impact their implementation in drug development programs. These studies are typically resource-intensive, requiring substantial financial investment, lengthy timelines, and complex operational logistics [12]. The rigid protocol specifications necessary for maintaining internal validity may limit generalizability to broader patient populations and real-world clinical settings, creating an efficacy-effectiveness gap between trial results and clinical practice applications [12].

Ethical considerations present additional challenges, particularly when investigating interventions for serious conditions with established effective treatments, where randomization to placebo or inferior care may be problematic [12]. Furthermore, certain patient populations or clinical contexts may be unsuitable for RCTs due to practical or ethical constraints, creating evidence gaps that require alternative methodological approaches. Recent regulatory trends have emphasized the importance of adequate US representation in global clinical trials, with concerns raised about applicability of results from trials conducted primarily outside the US to American patient populations [15]. This consideration has become increasingly relevant in multinational drug development programs, where differential treatment effects across geographical regions may complicate efficacy interpretation and regulatory assessment [15].

Regulatory Evolution and Contemporary Design Innovations

The regulatory landscape for RCTs continues to evolve, with increasing emphasis on innovative trial designs that enhance efficiency while maintaining methodological rigor. Adaptive trial designs that allow for modification based on interim analyses, enrichment strategies targeting specific patient subpopulations, and pragmatic elements that enhance real-world applicability are being encouraged by regulatory agencies [14]. These innovative approaches can potentially accelerate drug development while generating robust evidence for regulatory decision-making.

Recent regulatory considerations have highlighted the impact of variable uptake of subsequent therapies across geographical regions in global trials, which can significantly affect the interpretability of overall survival endpoints [15]. This variability, along with analysis of other endpoints less susceptible to such confounding (e.g., progression-free survival), should be carefully considered when determining a treatment regimen's benefit-risk profile [15]. For confirmatory trials required for accelerated approval verification, the FDA now generally requires trials to be "underway" at the time of accelerated approval to minimize the "vulnerability period" during which patients may receive therapies that ultimately lack demonstrated clinical benefit [14]. This regulatory evolution underscores the importance of proactive confirmatory trial planning and execution throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Methodological Decision Framework: Selecting Appropriate Trial Designs

Strategic Considerations for Design Selection

The choice between single-arm and randomized controlled trial designs represents a critical strategic decision in drug development programs, with significant implications for development timelines, resource allocation, regulatory pathways, and ultimate evidence strength. This decision should be guided by multiple considerations including the clinical context, available therapeutic alternatives, patient population characteristics, endpoint selection, and regulatory requirements [13] [14].

SATs may be appropriate when specific conditions are met: (1) the investigational treatment is expected to produce effects substantially larger than existing therapies, making threshold exceedance a meaningful indicator of clinical benefit; (2) the natural history or existing treatments are expected to produce negligible effects on the endpoint of interest, providing a near-zero baseline against which treatment effects can be clearly distinguished [13]. The latter scenario explains the historical use of SATs in end-stage oncology indications where no approved therapies exist and tumor response rates from natural history approach zero. In such contexts, achieving a meaningful objective response rate may constitute valid evidence of efficacy given the extremely low background response rate [13].

In contrast, RCTs are typically required when: (1) anticipated treatment effects are modest or incremental compared to existing therapies; (2) substantial background effects or disease variability exists; (3) validated surrogate endpoints with established correlation to clinical outcomes are unavailable; (4) comprehensive safety assessment requires direct comparison to control groups [12] [14]. The FDA's increasing preference for randomized designs, even in accelerated approval contexts, reflects recognition that RCTs provide more accurate efficacy and safety profiles, enabling robust benefit-risk assessments [14].

Decision Pathway for Trial Design Selection

Emerging Methodological Approaches and Hybrid Designs

Contemporary drug development increasingly utilizes methodological innovations that incorporate elements from both traditional RCTs and real-world evidence approaches. These hybrid models aim to balance methodological rigor with practical efficiency, enhancing the drug development ecosystem while maintaining robust evidence standards [14] [16].

The "one trial" approach represents a significant innovation, where a single randomized controlled trial efficiently generates evidence for both accelerated approval (based on intermediate endpoints) and traditional approval (based on clinical endpoints) [14]. This strategy can potentially streamline development pathways while providing the methodological benefits of randomization throughout the regulatory process. Adaptive designs that allow modification based on interim analyses, enrichment strategies targeting specific patient subpopulations, and pragmatic elements that enhance real-world applicability are being increasingly encouraged by regulatory agencies [14].

External control arms derived from real-world data sources offer another innovative approach, potentially augmenting single-arm trials with historical comparators when randomized controls are not feasible [16]. However, these methodologies require careful implementation and validation to ensure comparability and minimize bias [13] [16]. Real-world evidence derived from healthcare databases, electronic health records, and registries is increasingly recognized as complementary to traditional clinical trials, particularly for safety assessment, effectiveness comparison, and contextualizing trial findings within routine clinical practice [16]. When utilized in a balanced manner, these approaches can offer time- and cost-saving solutions for researchers, the healthcare industry, regulatory agencies, and policymakers while benefiting patients through more efficient therapeutic development [16].

Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Clinical Trial Design and Evidence Synthesis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Design Platforms | ClinicalTrials.gov, EU Clinical Trials Register | Protocol registration, results reporting, design transparency | Regulatory compliance, trial transparency, methodology documentation |

| Systematic Review Tools | Covidence, Rayyan, EndNote | Study screening, data extraction, reference management | Evidence synthesis, quality assessment, meta-analysis preparation |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R, Stata, RevMan | Meta-analysis, network meta-analysis, statistical modeling | Data synthesis, effect size calculation, heterogeneity assessment |

| Quality Assessment Instruments | Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Methodological rigor evaluation, bias assessment | Critical appraisal, evidence grading, sensitivity analysis |

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA, CONSORT, STROBE | Transparent reporting, methodology documentation | Manuscript preparation, protocol development, research dissemination |

| Real-World Data Platforms | Electronic Health Records, Disease Registries, Claims Databases | Naturalistic evidence generation, post-marketing surveillance | Comparative effectiveness research, safety monitoring, external controls |

Methodological Standards and Implementation Frameworks

The conduct and reporting of clinical trials and evidence syntheses require adherence to established methodological standards to ensure validity, reliability, and reproducibility. Reporting guidelines such as PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) provide minimum recommended items to promote clear, transparent, and reproducible descriptions of research methodology and findings [17]. Lack of transparency in systematic reviews reduces their quality, validity, and applicability, potentially leading to erroneous health recommendations and negative impacts on patient care and policy [17].

The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines similarly enhance transparency and reproducibility for randomized controlled trials, with recent updates reflecting methodological advances [18]. For network meta-analyses (NMAs), which enable comparative effectiveness assessment of multiple interventions, specific methodological guidance has rapidly evolved, with significant increases in published guidance since 2011, particularly regarding evidence certainty and NMA assumptions [19]. These methodological frameworks collectively enhance research quality, enabling critical appraisal and appropriate application of evidence to clinical and regulatory decision-making.

Recent advancements in evidence synthesis methods include the integration of artificial intelligence tools to improve efficiency and the development of specialized handbooks for diverse review types including qualitative evidence synthesis, prognosis studies, and rapid reviews [20]. Cochrane's methodological evolution reflects these developments, with new random-effects methods in RevMan, prediction intervals to aid interpretation, and updated Handbook chapters incorporating contemporary best practices [20]. These resources collectively support researchers in navigating the complexities of clinical evidence generation and synthesis, facilitating robust drug efficacy research aligned with current methodological standards.

The hierarchy of evidence provides an essential framework for navigating the complex landscape of comparative drug efficacy research, with single-arm trials and randomized controlled trials occupying distinct but complementary roles. SATs offer practical advantages in specialized contexts including rare diseases and serious conditions lacking therapeutic alternatives, but face significant methodological limitations in establishing causal inference and controlling bias [13]. In contrast, RCTs represent the gold standard for efficacy assessment through random allocation, blinding procedures, and controlled conditions that minimize bias and establish definitive causal relationships [12].

The evolving regulatory landscape reflects increasing preference for randomized designs even in accelerated approval pathways, emphasizing their value in providing comprehensive efficacy and safety profiles for robust benefit-risk assessment [14]. This evolution underscores the importance of strategic trial design selection aligned with clinical context, therapeutic alternatives, and regulatory requirements. Emerging methodological approaches including hybrid designs, adaptive trials, and real-world evidence integration offer promising avenues for enhancing drug development efficiency while maintaining methodological rigor [14] [16].

For drug development professionals, understanding this evidentiary hierarchy and its implications for research design is fundamental to generating compelling efficacy evidence, navigating regulatory pathways, and ultimately advancing therapeutic options for patients. By strategically applying appropriate methodological approaches throughout the drug development lifecycle, researchers can optimize evidence generation while maintaining scientific integrity and regulatory standards.

In the landscape of drug development, head-to-head clinical trials represent the gold standard for comparing the efficacy and safety of therapeutic interventions. These studies, where two or more active treatments are directly compared within the same trial, provide the most reliable evidence for clinical and health policy decision-making. Despite their scientific value, such trials remain notably absent for many drug classes and therapeutic areas.

This scarcity persists even as the number of treatment options expands across most therapeutic areas. The absence of direct comparative evidence creates significant challenges for clinicians, patients, and health policy makers who must navigate treatment choices without clear guidance on relative therapeutic merits [21]. This whitepaper examines the multidimensional barriers—financial, methodological, regulatory, and operational—that limit the conduct of head-to-head trials, and explores methodological alternatives that researchers employ when direct comparisons are not feasible.

Financial and Resource Constraints

Prohibitive Costs and Sample Size Requirements

Head-to-head trials designed to demonstrate non-inferiority or superiority between active treatments typically require substantially larger sample sizes and longer durations than placebo-controlled studies. This is particularly true when comparing drugs with similar mechanisms of action or when expecting modest between-group differences. The financial implications of these expanded trial requirements are substantial, creating significant disincentives for sponsors.

Table 1: Comparative Resource Requirements for Different Trial Designs

| Trial Design Aspect | Placebo-Controlled Trial | Head-to-Head Superiority Trial | Head-to-Head Non-Inferiority Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Sample Size | Smaller | Larger (often substantially) | Largest |

| Trial Duration | Shorter | Longer | Longest |

| Operational Complexity | Moderate | High | Highest |

| Cost Implications | Lower | Higher | Highest |

Beyond basic sample size considerations, the current investment climate for clinical research presents additional headwinds. The pharmaceutical industry faces reduced investment in clinical trials, creating particular challenges for small and medium-sized biotechs with limited cash reserves [22]. This financial pressure makes resource-intensive head-to-head comparisons increasingly unattractive from a business perspective, especially when alternative pathways to regulatory approval exist.

Market and Reimbursement Pressures

Recent legislative changes have further complicated the business case for head-to-head trials. Industry experts note that regulations like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the United States are impacting trial initiation decisions, with companies shifting focus toward "fewer, high-value therapeutic areas" [22]. When profitability must be maximized across a more limited portfolio, sponsors may deprioritize expensive comparative studies that could potentially show their product is not superior to existing alternatives.

This economic reality creates a fundamental tension between commercial interests and scientific needs. As Ariel Katz, CEO of H1, explains: "As pharmaceutical companies shift their focus toward fewer, high-value therapeutic areas in light of the IRA's drug price negotiations, the overall number of clinical trials will go down" [22]. This trend may indirectly reduce the number of head-to-head comparisons conducted, as sponsors prioritize trials with higher likelihood of commercial success over those addressing comparative effectiveness questions.

Methodological and Statistical Complexities

Challenges in Trial Design and Interpretation

Designing a head-to-head trial requires careful consideration of multiple methodological factors, including choice of endpoints, non-inferiority margins, and statistical powering. These studies often face interpretation challenges, particularly when conducted in heterogeneous patient populations or when using surrogate endpoints that may not fully capture clinically important differences.

The growing complexity of modern trials exacerbates these challenges. As noted by industry experts, "Trials are getting more complex and expensive as they target smaller, more specific patient populations, rely on larger and more diverse datasets, and navigate stricter global regulations" [22]. This complexity is particularly pronounced for advanced therapies like cell and gene treatments, which may require adaptive trial designs that differ substantially from traditional randomized controlled trial models [22].

The Gold Standard Versus Practical Realities

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) model remains the methodological gold standard, but its application to head-to-head comparisons presents unique challenges. Maintaining blinding can be difficult when comparing interventions with different administration routes or distinctive side effect profiles. Additionally, selecting appropriate comparator doses requires careful justification to avoid allegations of "dosing games," where one drug might be administered at suboptimal levels to make the other appear more effective.

For rare diseases, these methodological challenges are magnified. Kevin Coker, former CEO of Proxima Clinical Research, notes that in rare diseases, "you have a very small number of target patients" [23]. This fundamental limitation of patient availability makes adequately powered head-to-head comparisons statistically and practically infeasible in many cases, forcing researchers to consider alternative methodological approaches.

Regulatory and Commercial Influences

Regulatory Pathways and Approval Requirements

Drug registration in many worldwide markets primarily requires demonstration of efficacy against placebo or standard of care, not superiority over all active alternatives [21]. This regulatory reality creates limited incentive for sponsors to invest in head-to-head comparisons when approval can be obtained through less costly and risky pathways.

The situation is well-described in the scientific literature: "Drug registration in many worldwide markets being only reliant on demonstrated efficacy from placebo-controlled trials" represents a fundamental structural barrier to conducting head-to-head studies [21]. This regulatory framework essentially makes head-to-head trials optional rather than mandatory for market entry.

Strategic Commercial Considerations

Beyond regulatory requirements, commercial considerations significantly influence trial design decisions. Pharmaceutical companies may be reluctant to conduct studies that could potentially show their product is inferior to a competitor's, particularly when the drug is already approved and generating revenue. This risk aversion is especially pronounced for blockbuster drugs with substantial market share.

Additionally, the timing of head-to-head comparisons in a product's lifecycle presents strategic challenges. Early in a drug's development, sponsors may lack confidence in its competitive advantages, making them hesitant to invest in direct comparisons. Later in the lifecycle, when market position is established, there may be limited commercial incentive to conduct studies that could undermine existing marketing claims or potentially narrow the drug's approved indications.

Practical Operational Hurdles

Patient Recruitment and Retention

Patient recruitment represents one of the most consistent challenges in clinical research, particularly for head-to-head trials that may require larger sample sizes. Industry reports indicate that patient recruitment and retention remain among the biggest roadblocks to trial success, with the average trial still failing to meet its recruitment goals [24].

The recruitment challenge is multifaceted. Patients today are "more informed, but also more selective" amid "a flood of similar-sounding studies," making it difficult for any single trial to stand out [24]. Additionally, despite years of advocacy, many trials "still fail to recruit diverse study populations," creating both scientific and regulatory challenges [24]. These recruitment difficulties are compounded in head-to-head trials that may have more stringent eligibility criteria than placebo-controlled studies.

Globalization and Regulatory Heterogeneity

The increasing globalization of clinical trials introduces additional complexity for head-to-head comparisons. Zee Zee Gueddar, senior director commercial at IQVIA, notes that "one of the most prominent challenges will be the growing complexity of global trials, with sponsors needing to navigate an increasingly intricate regulatory environment across diverse international markets" [22].

Table 2: Operational Challenges in Global Head-to-Head Trials

| Challenge Category | Specific Barriers | Potential Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Heterogeneity | Differing requirements across countries; inconsistent data requirements; varying ethical review processes | Protocol amendments; delayed initiations; increased costs |

| Operational Complexity | Multiple languages; different standards of care; varied healthcare infrastructures | Data heterogeneity; implementation challenges; site management difficulties |

| Patient Diversity | Cultural attitudes toward research; genetic variations; comorbidity differences | Generalizability questions; recruitment variability; retention differences |

As Kevin Coker summarizes: "Running trials across different countries sounds great but navigating different regulations, cultures, and standards is no small feat" [22]. This operational complexity adds another layer of challenge to already difficult head-to-head comparisons.

Alternative Methods for Comparing Drug Efficacy

Indirect Comparison Methodologies

When head-to-head trials are unavailable, researchers have developed statistical methods for indirect treatment comparisons. These approaches allow for the estimation of relative treatment effects through common comparators, but each carries important limitations and assumptions.

Naïve direct comparisons, which directly compare results from separate trials without statistical adjustment, are considered methodologically unsound as they "break the original randomization" and are "subject to significant confounding and bias because of systematic differences between or among the trials being compared" [21].

Adjusted indirect comparisons preserve the randomization of the original trials by comparing the magnitude of treatment effect between two treatments relative to a common comparator. This method, while more methodologically rigorous than naïve comparisons, increases statistical uncertainty as "the statistical uncertainties of the component comparison studies are summed" [21].

Mixed treatment comparisons (also called network meta-analysis) use Bayesian statistical models to incorporate all available data for a drug, including data not directly relevant to the comparator drug. These approaches can reduce uncertainty but "have not yet been widely accepted by researchers, nor drug regulatory and reimbursement authorities" [21].

Methodological Framework for Indirect Comparisons

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between different comparison methodologies available when head-to-head trial data is lacking:

All indirect comparison methods share a fundamental assumption: "that the study populations in the trials being compared are similar" [21]. When this assumption is violated, all indirect comparisons may produce biased estimates of relative treatment effects.

Case Study: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

The Proliferation of Treatment Options Without Direct Comparisons

The treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) illustrates the challenges created by absent head-to-head evidence. As noted in the literature, "The introduction of several new drug classes (notably glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1] analogues and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 [DPP4] inhibitors) over the past several years has resulted in added complexity to therapeutic choice" [21].

Despite multiple drugs being available within and across these classes, "very few GLP-1 analogues and DPP4 inhibitors have been compared in head-to-head studies" [21]. This evidence gap "poses a challenge for clinicians, patients and health policy makers" who must make treatment decisions without clear comparative effectiveness data [21].

Applied Indirect Comparison Methodology

In this clinical context, researchers have employed indirect comparison methods to address evidence gaps. Kim et al. performed a multiple adjusted indirect comparison to compare sitagliptin with insulin in T2DM with respect to change in HbA1c [21]. Since sitagliptin had only been compared with placebo and insulin had only been compared with exenatide, the researchers used a connecting trial comparing exenatide with placebo to establish the indirect comparison.

This approach demonstrates the practical application of indirect methods but also highlights their limitations. Each comparison in the chain introduces additional statistical uncertainty, and the validity of the final comparison depends on the similarity of patient populations across all three trials included in the analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Approaches

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Effectiveness Research