Bridging the Evidence Gap: Methodological Strategies for Validating Real-World Evidence Against Randomized Controlled Trials

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Real-World Evidence (RWE) against the gold standard of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs).

Bridging the Evidence Gap: Methodological Strategies for Validating Real-World Evidence Against Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Real-World Evidence (RWE) against the gold standard of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). It explores the foundational strengths and limitations of both data sources, details advanced methodological approaches like target trial emulation and privacy-preserving record linkage, addresses key challenges in data quality and bias, and presents frameworks for the comparative assessment of RWE validity. As regulatory bodies increasingly accept RWE, this guide aims to equip scientists with the tools to rigorously generate and evaluate real-world data, thereby enhancing its reliability for regulatory decision-making, label expansions, and understanding long-term treatment effectiveness in diverse patient populations.

Understanding the Evidence Landscape: The Complementary Roles of RCTs and RWE

Troubleshooting Guides

Addressing Threats to Internal Validity

Problem: Selection Bias and Poor Generalizability

- Issue: RCT samples are often highly filtered and unrepresentative of real-world patients due to stringent eligibility criteria. This occurs because patients may be excluded if they are suicidal, have psychotic symptoms, have major medical comorbidity, have concurrent substance use disorders, or have personality disorders [1].

- Troubleshooting: Scrutinize the CONSORT diagram to understand screening and recruitment filtration. Examine how many patients were obviously ineligible and not formally screened, as this creates a false impression of external validity [1].

- Prevention Protocol: Implement broad eligibility criteria where ethically and scientifically justified. Report complete pathway-to-recruitment data to allow judgment about generalizability [2].

Problem: Bias in Non-Blindable Interventions

- Issue: For interventions like psychotherapy, yoga, meditation, and acupuncture, patients cannot be blinded to their treatment assignment. This leads to contaminated placebo responses shaped by preexisting beliefs and expectations, seriously compromising internal validity [1].

- Troubleshooting: Monitor and report differential dropout rates between groups before treatment begins, as this indicates compromised randomization due to patient treatment preferences [1].

- Prevention Protocol: Consider alternative study designs (e.g., preference trials) or use active comparators rather than waitlisted controls to balance expectancy effects [1].

Problem: Post-Randomization Biases

- Issue: Randomization integrity deteriorates after trial commencement through events such as differential dropout (adverse events in drug groups, inefficacy in placebo groups), unequal use of rescue medications, and unreported concomitant treatments [1].

- Troubleshooting: Implement rigorous monitoring of rescue medication use, reasons for dropout, and treatment adherence. Consider collecting biological samples (e.g., drug levels) to detect unreported medication use [1].

- Prevention Protocol: Use statistical methods like imputation for missing data and plan sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of post-randomization confounding [1].

Problem: Faulty Maintenance Therapy Trial Design

- Issue: When clinically stabilized subjects are abruptly switched to placebo versus continuing active treatment, internal validity is compromised due to physiological perturbations from treatment discontinuation rather than true drug efficacy [1].

- Troubleshooting: Critically evaluate maintenance therapy RCTs for rapid discontinuation designs that may heighten relapse risk independent of true drug efficacy [1].

- Prevention Protocol: Utilize randomized discontinuation designs with gradual taper periods rather than abrupt switches to placebo [1].

Mitigating Limitations in Real-World Evidence Validation

Problem: Reconciling RCT Efficacy with RWE Effectiveness

- Issue: RCTs measure efficacy under ideal conditions while RWE captures effectiveness in routine practice, leading to potentially conflicting results [3] [4].

- Troubleshooting: Clearly distinguish between efficacy (can it work under ideal conditions?) and effectiveness (does it work in real-world practice?) when interpreting apparently discordant results [4].

- Prevention Protocol: Design pragmatic trials that blend RCT methodology with real-world practice elements. Use RWE to inform RCT design by identifying appropriate patient populations and comparators [5] [6].

Problem: Confounding in RWE Studies

- Issue: Observational studies used to generate RWE are vulnerable to confounding by indication, severity, and other unmeasured factors [5].

- Troubleshooting: Employ causal inference methods, including directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to explicitly define confounding structures, and use E-values to assess robustness to unmeasured confounding [5].

- Prevention Protocol: Pre-specify analysis plans using methods like propensity score matching, instrumental variables, or difference-in-differences to address confounding [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: If RCTs have so many limitations, why are they still considered the gold standard? RCTs remain the best available design for establishing causal inference because randomization, when properly implemented, balances both known and unknown confounding factors at baseline. This provides superior internal validity compared to observational designs, despite acknowledged limitations [1] [7] [8].

Q2: How can we assess whether a specific RCT's findings apply to our patient population? Carefully examine the study's eligibility criteria, recruitment pathway (how patients entered the trial), participant flow (CONSORT diagram), and baseline characteristics. Consider whether your patient would have met inclusion criteria and whether the treatment protocols are feasible in your setting [1] [2].

Q3: What are the most underappreciated threats to RCT validity? Post-randomization biases are frequently overlooked. These include differential dropout, non-adherence, use of rescue medications, and exposure to external factors that occur after randomization but can seriously compromise the balance achieved through initial random assignment [1].

Q4: How can RWE and RCTs be used together most effectively? RWE can inform RCT design by identifying appropriate patient populations, endpoints, and comparators. Conversely, RCT findings can be validated and extended through RWE studies examining long-term outcomes, rare adverse events, and effectiveness in diverse populations [3] [4] [5].

Q5: What methodological innovations are addressing RCT limitations? Adaptive trial designs, platform trials, and sequential designs are making RCTs more flexible and efficient. Meanwhile, the integration of electronic health records into clinical trials is facilitating more pragmatic designs that better reflect real-world practice [5].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Validating RWE Against RCT Findings

Objective: To systematically compare treatment effects derived from real-world evidence with those from randomized controlled trials for the same clinical question.

Methodology:

- Define Clinical Question: Precisely specify population, intervention, comparator, and outcomes [4]

- Identify RCTs: Conduct systematic literature review to identify relevant RCTs

- Source RWE: Identify appropriate real-world data sources (electronic health records, claims data, registries) capturing the same clinical scenario [4] [6]

- Harmonize Definitions: Standardize patient eligibility criteria, treatment definitions, and outcome measurements across data sources

- Analyze RWE: Apply appropriate causal inference methods (propensity score matching, weighting, or stratification) to address confounding [5]

- Compare Effects: Quantitatively compare treatment effect estimates using meta-analytic approaches

- Investigate Heterogeneity: Explore sources of differing results through subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Protocol for Addressing Post-Randomization Bias in RCTs

Objective: To identify, measure, and account for biases introduced after randomization in clinical trials.

Methodology:

- Pre-specify Monitoring: Define potential post-randomization biases (rescue medication use, crossover, dropout) in statistical analysis plan [1]

- Implement Enhanced Monitoring: Track and document reasons for all protocol deviations, dropouts, and concomitant treatments

- Collect Supplemental Data: Where feasible, use biological assays to verify adherence and detect unreported medication use [1]

- Apply Statistical Methods: Use appropriate methods (e.g., inverse probability weighting, multiple imputation) to account for missing data not missing at random

- Conduct Sensitivity Analyses: Test robustness of findings under different assumptions about post-randomization events

Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of RCTs and Real-World Evidence

| Characteristic | Randomized Controlled Trials | Real-World Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Establish efficacy [3] | Measure effectiveness [3] |

| Setting | Experimental, highly controlled [3] [4] | Real-world clinical practice [3] [4] |

| Patient Selection | Strict inclusion/exclusion criteria [1] [4] | Broad, representative populations [4] |

| Treatment Protocol | Fixed, per protocol [3] [4] | Variable, at physician's discretion [3] [4] |

| Comparator | Placebo or selective active control [3] | Multiple alternative interventions [3] |

| Patient Monitoring | Continuous, intensive [3] [4] | Routine clinical practice [3] [4] |

| Key Strength | High internal validity [1] [8] | High external validity [4] [5] |

| Main Limitation | Limited generalizability [1] [2] | Potential for confounding [5] |

Table 2: Common RCT Limitations and Methodological Solutions

| Limitation Category | Specific Issues | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| External Validity | Narrow eligibility criteria [1]; unrepresentative settings [2] | Pragmatic trials; broad eligibility criteria [2] [5] |

| Internal Validity | Faulty randomization [8]; poor blinding [1]; post-randomization biases [1] | Allocation concealment [8]; statistical correction methods [1] |

| Intervention-Related | Non-blinding of patients [1]; abrupt treatment switches [1] | Active comparators; randomized discontinuation designs [1] |

| Measurement Issues | Use of proxy outcomes [1]; inappropriate rating instruments [1] | Patient-centered outcomes; validated instruments [1] |

Visualizations

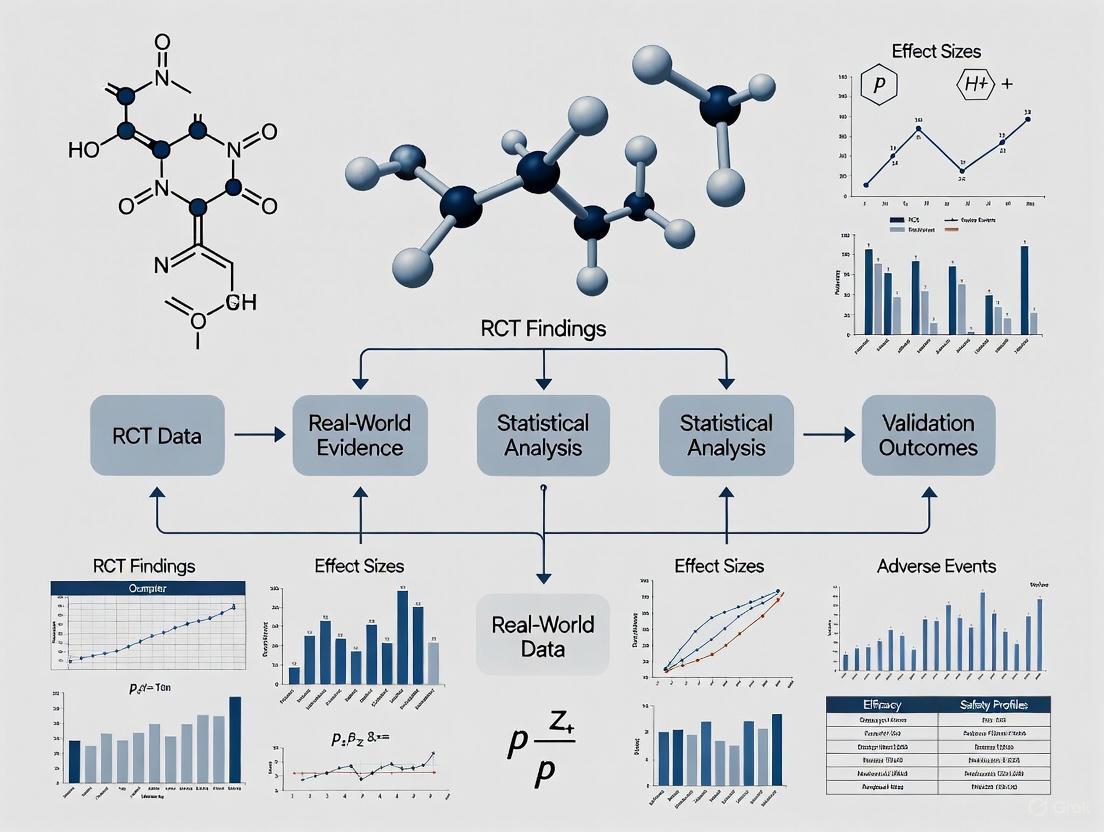

Relationship Between RCTs and RWE in Evidence Generation

Relationship Between RCT and RWE Evidence

RCT Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

RCT Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Methodological Tools for RCT and RWE Research

| Tool Category | Specific Methods | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Pragmatic trials [5] | Blend RCT rigor with real-world relevance | Effectiveness research; comparative effectiveness |

| Study Design | Adaptive designs [5] | Modify trial parameters based on interim data | Efficient drug development; rare diseases |

| Bias Control | Allocation concealment [8] | Prevent foreknowledge of treatment assignment | Minimizing selection bias in RCTs |

| Bias Control | Causal inference methods [5] | Address confounding in observational data | Generating valid RWE from real-world data |

| Data Sources | Electronic health records [4] [6] | Provide comprehensive clinical data | RWE generation; patient recruitment |

| Data Sources | Clinical registries [4] [6] | Systematically collect disease/treatment data | Post-market surveillance; comparative effectiveness |

| Statistical Methods | Propensity score analysis [5] | Balance confounders in non-randomized studies | RWE validation against RCT findings |

| Statistical Methods | Fragility Index [7] | Quantify robustness of RCT results | Critical appraisal of small RCTs |

| Outcome Assessment | Patient-reported outcomes [6] | Capture patient perspective on treatment impact | Complementing clinical outcomes in both RCTs and RWE |

| SBI-797812 | SBI-797812, CAS:2237268-08-3, MF:C19H22N4O4S, MW:402.469 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tedalinab | Tedalinab|Selective CB2 Agonist|RUO | Bench Chemicals |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RWD Challenges and Solutions

Data Quality and Completeness

| Challenge | Root Cause | Impact on Research | Solution | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Data | Data not collected during routine care; fragmented health records [9] | Introduces selection bias; reduces statistical power [9] | Implement multiple imputation techniques; use data linkage (PPRL) to fill gaps [9] | Compare characteristics of patients with complete vs. missing data; perform sensitivity analyses [10] |

| Inconsistent Data | Lack of standardization across different healthcare systems and coding practices (e.g., ICD-10, SNOMED) [10] | Leads to misclassification of exposures, outcomes, and confounders [9] | Use AI/NLP tools to standardize unstructured data from clinical notes; map to common data models (e.g., OHDSI, Sentinel) [11] [10] | Conduct validation sub-studies to check coding accuracy against source documents [4] |

| Lack of Clinical Granularity | Claims data designed for billing, not research; EHRs may lack lifestyle or socio-economic factors [11] [12] | Inability to control for key confounders or accurately phenotype patients [9] | Link RWD to specialized registries or patient-reported outcomes [11] [13] | Compare RWD-derived phenotypes with adjudicated clinical outcomes in a sample [11] |

Methodological and Confounding Issues

| Challenge | Root Cause | Impact on Research | Solution | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channeling Bias & Confounding by Indication | Lack of randomization; treatments chosen based on patient prognosis [9] [4] | Distorts true treatment effect; estimated effects may reflect patient differences, not drug efficacy [9] | Employ Target Trial Emulation: pre-specify a protocol mimicking an RCT [12] [9] | Compare RWE results with existing RCT findings on the same clinical question [14] |

| Time-Related Biases | Incorrect handling of immortal time or time-window biases in longitudinal data [9] | Can lead to significantly inflated or deflated estimates of treatment effectiveness [9] | Apply rigorous longitudinal study designs (e.g., new-user, active comparator designs) [11] | Conduct quantitative bias analysis to model the potential impact of unmeasured confounding [14] |

| Generalizability vs. Internal Validity Trade-off | RWD includes broader populations but with more confounding [13] | High external validity may come at the cost of reduced internal validity [13] | Use Propensity Score Matching/Weighting to create balanced comparison cohorts from real-world populations [12] [14] | Assess covariate balance after weighting/matching; report on both internal and external validity [13] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data and Methodology

Q1: How can I assess whether a real-world data source is "fit-for-purpose" for my specific research question? Begin by evaluating the provenance, quality, and completeness of the RWD source for the key variables you need [9]. For a study on drug efficacy, the data must accurately capture the exposure, the primary outcome, and the major confounders. If key confounders are not recorded, the dataset may be unsuitable for causal inference, though it might still be useful for descriptive analyses. Always pre-specify a quality assessment plan [10].

Q2: What is the single most important methodological practice to improve the robustness of RWE? Target Trial Emulation is considered a gold-standard framework [12]. Before analyzing the data, you should write a detailed protocol that mimics a hypothetical randomized controlled trial, explicitly defining all components: eligibility criteria, treatment strategies, assignment procedures, outcomes, follow-up, and causal contrast of interest. This rigorous design step minimizes ad hoc, data-driven analyses that are prone to bias [12] [9].

Q3: When is it appropriate to use an external control arm built from RWD, and what are the key pitfalls? External control arms (ECAs) are particularly valuable in oncology, rare diseases, and single-arm trials where randomization is unethical or impractical [15] [14]. The primary pitfall is inadequate confounding control due to systematic differences between the trial population and the external control. To mitigate this, ensure the RWD is from a similar clinical context and use robust statistical methods like propensity score weighting on baseline patient characteristics to improve comparability [15].

Validation and Regulation

Q4: How can I validate the findings from my RWE study against RCT evidence? The most direct method is to conduct a RWE replication study of an existing RCT whose results are known. Design your RWE study to emulate the target RCT as closely as possible in terms of population, intervention, comparator, and outcome. Then, compare the effect estimates. Consistency between the RWE and RCT findings strengthens the credibility of the RWE. Discrepancies require careful investigation into sources, such as unmeasured confounding or differences in patient populations [14].

Q5: What is the current regulatory stance on using RWE to support new drug applications? Major regulatory agencies, including the FDA and EMA, have established frameworks for using RWE [11] [4]. The acceptance of RWE is growing, particularly for supporting label expansions (as with palbociclib for male breast cancer) and post-marketing safety studies [11] [4]. Using RWE to demonstrate efficacy for new drug approvals is less common but increasingly accepted in specific contexts, especially when RCTs are not feasible. The key regulatory requirement is that the RWE must be "fit for purpose" and meet rigorous scientific standards for data quality and study design [11] [13].

Key Analytical Workflows

Workflow for Generating Valid RWE

The following diagram illustrates the core methodological workflow for transforming raw RWD into validated real-world evidence.

RWE Validation Pathway Against RCTs

This diagram outlines a systematic approach for validating Real-World Evidence findings by benchmarking them against Randomized Controlled Trial results.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

The following table details key methodological "reagents" and their application in RWE generation and validation.

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage (PPRL) | Links patient records across disparate data sources (e.g., EHRs, claims, registries) without exposing personal identifiers, creating a more comprehensive patient journey [9]. | Essential for overcoming data fragmentation. Tokens must be created consistently across data partners to ensure accurate matching while complying with privacy regulations [9]. |

| Common Data Models (CDMs) | Standardizes the structure and content of disparate RWD sources (e.g., OMOP-CDM used by OHDSI and EHDEN), enabling scalable, distributed analysis [11]. | Reduces interoperability challenges. Requires significant investment to map local data to the common model, but enables large-scale network studies [11] [4]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Extracts structured information (e.g., disease severity, patient status) from unstructured clinical notes in EHRs, unlocking rich clinical detail [11] [15]. | Critical for phenotyping and capturing confounders not in structured data. Models require training and validation for specific use cases and clinical terminologies [10] [15]. |

| Propensity Score Methods | A statistical technique to simulate randomization by creating a balanced comparison group, reducing selection bias by accounting for measured confounders [12] [14]. | Only balances measured covariates. The quality of the resulting evidence hinges on the researcher's ability to capture and include all key confounders in the model [9]. |

| Synthetic Control Arms | Uses existing RWD to construct a virtual control group for a single-arm trial, especially useful in rare diseases or oncology [11] [15]. | The validity depends on the similarity between the trial patients and the RWD population. Rigorous statistical adjustment is required to minimize channeling bias [15] [14]. |

Understanding the Gap: Efficacy vs. Effectiveness

What is the efficacy-effectiveness gap in clinical research?

The efficacy-effectiveness gap refers to the observed differences between how a medical intervention performs under the ideal, controlled conditions of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and how it performs in routine clinical practice. Efficacy is what is measured in RCTs (can it work?), while effectiveness is what happens in real-world settings (does it work in practice?) [11].

This gap arises because RCTs and real-world evidence (RWE) studies differ fundamentally in their design, population, and setting, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Differences Between RCTs and Real-World Evidence (RWE) Studies [16] [11]

| Aspect | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Real-World Evidence (RWE) Study |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Demonstrate efficacy under ideal, controlled settings [11] | Demonstrate effectiveness in routine care [11] |

| Population & Criteria | Narrow inclusion/exclusion criteria; homogeneous subjects [16] [11] | Broad, few strict criteria; reflects typical, diverse patients [16] [11] |

| Setting & Protocol | Experimental research setting with fixed, prespecified intervention [11] | Actual practice with variable treatment based on physician/patient choices [11] |

| Patient Monitoring | Rigorous, scheduled follow-up [11] | Variable follow-up at clinician discretion [11] |

| Data Collection | Structured case report forms for research [16] | Routine clinical records, claims data, patient registries [16] [17] |

| Key Strength | High internal validity; strong causal inference due to randomization [16] | High external validity; generalizability to broader populations [16] |

Troubleshooting Common RWE Validation Challenges

FAQ: Why is validation of Real-World Evidence against RCT findings necessary?

Validation is crucial because RWE is generated from real-world data (RWD) that are often collected for purposes other than research (e.g., clinical care, billing). Without validation, findings from RWE studies may be influenced by confounding variables, missing data, or other biases that can lead to incorrect conclusions about a treatment's safety or effectiveness [16] [18]. Validation against the gold-standard RCT helps establish that the RWE is fit-for-purpose and reliable for regulatory and clinical decision-making [17].

The most common and challenging sources of bias in RWE studies include:

- Confounding: When an unmeasured factor is associated with both the treatment and the outcome. RCTs minimize this through randomization [18].

- Selection Bias: Occurs if the study population is not representative of the target population, often due to how data are captured in EHRs or claims databases [11].

- Information Bias: Results from misclassification of exposures or outcomes, which can happen if coding practices in claims data are inconsistent [19].

FAQ: My RWE study results are inconsistent with prior RCTs. What should I investigate first?

When facing discrepant results, systematically investigate these potential causes first:

- Study Population Differences: Compare the baseline characteristics (e.g., age, comorbidities, disease severity, prior treatments) of your RWE cohort with the RCT population. RWE often includes older, sicker patients with more co-morbidities [16] [20].

- Treatment Patterns: Analyze treatment adherence, dose modifications, and treatment duration in the real world, as these often differ from the strict RCT protocol [11].

- Comparator Group Appropriateness: Ensure the real-world comparator group is a valid approximation for the RCT control arm. Use causal inference methods to balance baseline characteristics [18].

Experimental Protocols for RWE Validation

Protocol: Designing a Study to Validate RWE Against an RCT

This protocol outlines a methodology for assessing the reliability of RWE by benchmarking it against an existing RCT.

1. Define the Objective and Identify a Reference RCT

- Clearly state the clinical question (e.g., "Does drug X improve overall survival versus standard care in population Y?").

- Identify a pivotal RCT that has established efficacy for this question. The RCT's protocol and statistical analysis plan should be available for comparison [21].

2. Emulate the RCT Design Using RWD

- Population Emulation: Apply the RCT's key eligibility criteria to the RWD source (e.g., EHR or claims database) to create a "RCT-like" cohort [20].

- Treatment and Comparator Definition: Clearly define the initiation of treatment and identify a comparable control group within the RWD.

- Outcome Ascertainment: Ensure the outcome (e.g., overall survival, progression-free survival) can be accurately captured from the RWD [18].

3. Implement Advanced Analytical Methods

- Use techniques like propensity score matching or weighting to balance the baseline characteristics between the treatment and comparator groups in the RWD, mimicking the randomization of the RCT [11] [18].

- Conduct extensive sensitivity analyses to test how robust the findings are to potential unmeasured confounding [18].

4. Compare and Interpret Results

- Quantitatively compare the treatment effect estimates (e.g., hazard ratio for survival) from the RWE analysis and the reference RCT.

- A high degree of consistency between the two increases confidence in the RWE. If a gap exists, investigate the potential sources (see FAQ above) [20].

Protocol: Framework for Selecting an RWE Assessment Tool

With numerous tools available, this protocol helps select the right one for your study's needs [18].

1. Define the Use Case Determine the primary goal of the assessment:

- Protocol Development: Tools that help design a robust RWE study.

- Study Reporting: Checklists to ensure transparent and complete reporting of methods and results.

- Quality Assessment: Tools to critically appraise the reliability of an existing RWE publication.

2. Evaluate Tool Characteristics

- Domains Covered: Ensure the tool addresses key areas like data source suitability, confounding control, and statistical methods.

- Scoring System: Check if it uses a binary (yes/no) or scaled scoring system.

- Validation Status: Prefer tools that have been formally validated.

- Intended User: Some tools are for study authors, others for reviewers or regulators [18].

3. Apply the Tool Systematically

- Use the selected tool as a guide during the study design, manuscript writing, or critical appraisal phase.

- Document responses to each item in the tool to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Table 2: Categories of RWE Assessment Tools [18]

| Tool Category | Primary Use Case | Key Characteristics | Example Tools (from literature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Development | Guiding the design and planning of a new RWE study. | Often detailed frameworks and templates. | ISPOR Good Practices, FDA RWE Framework [17] [18] |

| Study Reporting | Ensuring complete and transparent reporting of completed RWE studies. | Typically structured as checklists. | CONSORT-ROUTINE, ESMO-GROW [18] |

| Quality Assessment | Critically appraising the reliability and risk of bias in published RWE. | May include scoring systems to grade quality. | ROBINS-I, NICE Checklist [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RWE Validation

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RWE Validation

| Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Application in RWE Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Methods | A statistical technique that models the probability of receiving a treatment given observed baseline characteristics [11]. | Creates a balanced pseudo-population in RWD, mimicking the randomization of an RCT to reduce confounding by indicated factors [11] [18]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis | A method to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to change the study conclusions [18]. | Tests the robustness of RWE findings and provides evidence for or against causal inference in the absence of randomization [18]. |

| Common Data Models (CDMs) | Standardized structures for organizing healthcare data from diverse sources (e.g., EHR, claims). | Enables large-scale, reproducible analysis across different RWD networks (e.g., OHDSI, FDA Sentinel) [11] [22]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | AI-based technology that extracts structured information from unstructured clinical text (e.g., physician notes) [11]. | Uncovers critical clinical details not found in coded data alone, improving phenotyping accuracy and outcome ascertainment [11]. |

| Structured Treatment Plans | Pre-registered study protocols and statistical analysis plans published before analysis begins. | Mitigates bias from data dredging and post-hoc analysis choices; aligns with best practices for regulatory-grade RWE [21] [18]. |

| Thiol-PEG3-acid | Thiol-PEG3-acid|HS-PEG3-COOH Reagent|1347750-82-6 | |

| TIQ-15 | TIQ-15, MF:C23H32N4, MW:364.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Validation Concepts

What is the core purpose of validating Real-World Evidence (RWE) against Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) findings? The core purpose is to establish whether RWE can provide credible, complementary evidence in situations where RCTs have limitations, such as lack of external validity, ethical constraints in control arms, or the use of non-standard endpoints. Validation ensures that RWE can reliably support regulatory and health technology assessment (HTA) decisions by confirming that its findings are consistent and scientifically rigorous [23] [24].

When is the use of RWE most appropriate to complement an RCT? RWE is most appropriate in specific complex clinical situations. The table below categorizes these scenarios and the corresponding RWE approaches.

Table: Complex Clinical Situations and Corresponding RWE Approaches

| Complex Clinical Situation | Category | Recommended RWE Approach |

|---|---|---|

| RCT population differs from local clinical practice population [23] [24] | Limited External Validity of RCTs | Conduct an environmental observational study to describe the local population, or transport/extrapolate RCT results to the target population of interest [23] [24]. |

| Conducting a randomized controlled trial is unfeasible or unethical (e.g., rare diseases) [23] [24] | Treatment Comparison Issues | Create an External Control Arm (ECA) from RWD for a single-arm trial or emulate a target trial using RWD [23] [25] [24]. |

| The clinical trial uses a surrogate endpoint (e.g., progression-free survival) instead of a gold-standard endpoint (e.g., overall survival) [23] [24] | Non-Standard Endpoints | Use RWE to evaluate the correlation between the surrogate endpoint and the gold-standard endpoint in a real-world setting post-approval [23] [24]. |

| The comparator drug used in the RCT is no longer the standard of care at the time of HTA assessment [23] [24] | Treatment Comparison Issues | Conduct a post-launch RWE study to directly compare the new drug against the current standard of care [23] [24]. |

Regulatory and Methodological Considerations

What are the most critical methodological factors for ensuring RWE credibility? Robust methodology is paramount to address inherent biases in observational data. Key considerations include [23] [25] [24]:

- Confounding Identification: Use tools like Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) to identify potential confounding factors.

- Advanced Statistical Techniques: Apply methods like propensity score matching, inverse probability of treatment weighting, or G-computation to adjust for differences between treatment groups.

- Sensitivity Analyses: Perform analyses to quantify the impact of potential residual biases, such as unmeasured confounding.

- Prespecified Protocols: Finalize study protocols and statistical analysis plans before initiating data analysis to avoid bias from selectively reporting results [25].

What are the key regulatory expectations for using RWE in a submission? Regulators like the FDA emphasize several best practices [17] [25]:

- Early and Ongoing Engagement: Engage with regulators early to discuss and align on the study design, data sources, and methodological approach before initiating the study [25].

- Fit-for-Purpose Data: Conduct thorough feasibility assessments to justify that the selected data source is appropriate for the research question [25].

- Data Quality and Reliability: Ensure data are accurate, complete, and traceable. The FDA must be able to access and verify study records [25].

- Internal Validity: Implement rigorous methodologies to identify and mitigate biases, ensuring the study's findings are valid [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Addressing Concerns about External Validity

Problem: The results from my RCT may not be generalizable to the broader patient population in clinical practice.

Solution: Use RWE to assess and enhance transportability.

- Define the Target Population: Clearly describe the "real-world" target population using RWD sources like electronic health records or registries [23] [24].

- Identify Differences: Compare the characteristics of the RCT population and the target RWD population to identify key differences (e.g., age, comorbidities, ethnicity) [23] [24].

- Apply Statistical Transportability Methods: Use quantitative techniques, such as weighting or outcome regression models, to transport the RCT treatment effect estimate to the target population. This helps bridge the efficacy-effectiveness gap [24].

Challenge: Validating a Study with a Single-Arm Trial

Problem: I am developing a treatment for a rare disease where a concurrent control arm is not feasible. Regulatory agencies are questioning the validity of the observed effects.

Solution: Construct a robust External Control Arm (ECA) from RWD.

- Ensure Natural History is Well-Defined: The ECA approach is most defensible when the natural history of the disease is highly predictable and well-characterized [25].

- Prioritize Comparability: The treatment group and the ECA must be as similar as possible. Carefully select the RWD source to ensure granular data on patient characteristics, disease severity, and prior lines of therapy are available [25] [24].

- Mitigate Bias Proactively: Address potential selection bias and confounding through the design and analysis plan [24]. Use propensity score methods to match the ECA patients to the single-arm trial patients on key prognostic variables [23] [24].

- Engage Regulators Early: Seek agreement from regulators on the choice of data source, ECA construction methodology, and analysis plan before finalizing the study design [25].

Challenge: Responding to a Regulatory Query on Data Quality

Problem: A regulator has questioned the reliability and provenance of the RWD used in our submission.

Solution: Demonstrate comprehensive data quality assurance.

- Document Data Provenance: Maintain a clear record of the data's origin, including how it was collected, processed, and transformed [25].

- Ensure Traceability: The data must be traceable back to the original source records. Be prepared for a potential audit where regulators may request to verify study records [25].

- Transform Data to Standards: Transform the RWD into compliant formats, such as those required by the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC), to facilitate regulatory review [25] [26].

- Provide a Feasibility Assessment Report: Share the results of the fit-for-purpose assessment that justified the selection of your specific data source for the research question [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RWE Validation

Table: Key Methodological and Regulatory Solutions for RWE Studies

| Tool / Solution | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Methods [23] [24] | A statistical technique to balance covariates between a treatment group and an RWD-based control group, reducing selection bias. | Choose the appropriate method (matching, weighting, stratification). Always include sensitivity analyses to test robustness. |

| Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) [23] [24] | A visual tool to map out assumed causal relationships, helping to identify and minimize confounding bias before analysis. | Requires strong subject-matter knowledge to build correctly. It is a prerequisite for robust adjustment. |

| Sensitivity Analysis [23] [24] | A set of analyses to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to change the study conclusions. | Essential for establishing result robustness. Methods include E-value and probabilistic sensitivity analysis. |

| Structured Protocol & SAP [25] | A pre-defined, detailed study protocol and statistical analysis plan (SAP) finalized before data analysis. | Critical for regulatory acceptance. Prevents data dredging and preferential reporting of results. |

| Good Clinical Practice (GCP) for RWD Studies [25] | A framework for ensuring study conduct and data integrity meet regulatory standards, even in non-interventional settings. | Involves study monitoring, compliance with final protocols, and maintaining an audit trail. |

| TMP778 | TMP778|Potent RORγt Inhibitor|For Research Use | TMP778 is a potent, selective RORγt inverse agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation and IL-17 production. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| TMP920 | TMP920|RORγt Inhibitor |

Experimental Protocol: Workflow for Validating an External Control Arm

The following diagram outlines a high-level workflow for designing a study that uses RWD to build an External Control Arm, incorporating key validation and regulatory steps.

Protocol Title: Validation of an External Control Arm Derived from Real-World Data for a Single-Arm Trial.

Objective: To generate robust comparative evidence for a new therapeutic agent in a rare disease by constructing a validated ECA from RWD, suitable for regulatory decision-making.

Methodology:

- Define and Align (Pre-Study):

- ECA Construction:

- Select a high-quality RWD source that is fit-for-purpose. The data must be relevant, with sufficient granularity on patient characteristics, disease history, and prior treatments to enable adequate adjustment for confounding [23] [25] [24].

- Apply advanced statistical methods, such as propensity score matching or weighting, to balance the ECA and the single-arm trial population on key prognostic factors. The goal is to achieve a high degree of comparability between the groups [23] [24].

- Analysis and Validation:

- Execute the pre-specified analysis to compare outcomes between the treatment group and the ECA.

- Conduct extensive sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of potential unmeasured confounding and other biases on the study results. This is essential for establishing the robustness of the findings [23] [24].

- Reporting and Submission:

- Submit the complete study package to regulators, ensuring full transparency and providing access to patient-level data in compliant formats to facilitate review [25].

Logical Framework: Integrating RWE into the Clinical Development Lifecycle

The following diagram illustrates the strategic points in a product's lifecycle where RWE can be generated and integrated with RCT evidence to build a comprehensive evidence package.

Methodological Frameworks for RWE Validation: From Design to Analysis

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Common TTE Challenges

This section addresses specific, practical issues researchers may encounter when designing and implementing a Target Trial Emulation (TTE) study, providing guidance on their mitigation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How do I handle a situation where my real-world data (RWD) source lacks a key clinical variable needed for confounding adjustment?

- Issue: This is a fundamental data limitation leading to potential unmeasured or residual confounding [27] [28]. The target trial framework itself cannot resolve this problem, as it relates to data quality rather than study design [29] [28].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- A Priori Confounder Selection: Define adjustment variables based on the target trial protocol and subject-matter knowledge, not just data availability [30].

- Quantitative Bias Analysis: Perform sensitivity analyses to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away the observed effect [30].

- Data Linkage: Explore linking your primary RWD source to other datasets (e.g., linking claims data with a clinical registry) that might contain the missing variable [27].

- Transparent Reporting: Clearly state the limitation and list the potential confounders that could not be adjusted for in your analysis [27].

FAQ 2: What should I do if emulating the "intention-to-treat" (ITT) principle leads to a large loss of participants after propensity score matching?

- Issue: Strict emulation of the target trial's eligibility criteria and treatment strategies can sometimes result in a small analytical sample, reducing statistical power and potentially affecting representativeness [27].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Diagnose the Bottleneck: Identify which specific eligibility criterion (e.g., a specific comorbidity) or treatment definition is causing the high exclusion rate.

- Check Population Overlap: Use propensity score histograms to visually assess the overlap between treatment and comparator groups. A large loss of patients may indicate a lack of clinical equipoise in the real world [27].

- Consider Sensitivity Analyses: Explore the robustness of your results using different analytical approaches, such as inverse probability weighting instead of matching, which uses data from all eligible individuals [30].

FAQ 3: Why are my TTE results statistically different from a published Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) on the same intervention?

- Issue: Despite a well-emulated design, discrepancies with RCT results can arise [31].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Verify Emulation Fidelity: Re-check that all key components of the target trial (eligibility, treatment strategy, time-zero, outcome) were correctly emulated. A common pitfall is miscalibrating the "time-zero" [27] [32].

- Investigate Residual Confounding: Revisit the possibility of unmeasured confounding or confounding by indication, which remains a key limitation of TTE [27].

- Assess Differences in Patient Population: The RCT may have included a highly selected population. Your RWD may include a broader, real-world population with different characteristics and risk profiles, leading to different effect estimates [27] [31].

- Check for Changes in Practice: The TTE might capture the drug's use in a different era or clinical context post-approval, where prescribing patterns or concomitant care have shifted [31].

Experimental Protocols for Key TTE Analyses

This section provides a detailed methodological blueprint for a core TTE study, focusing on comparing the effectiveness of two treatments.

Detailed Protocol: Comparative Effectiveness of Drug A vs. Drug B

This protocol outlines the steps to emulate a hypothetical RCT comparing two treatments using a healthcare database.

1. Target Trial Protocol Specification: The first step is to explicitly define the protocol of the hypothetical target trial that would ideally answer the causal question [29] [30] [32].

- Eligibility Criteria: Define inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., adults with first diagnosis of condition X, no prior use of Drug A or B, no contraindications).

- Treatment Strategies: Clearly define the treatment strategies for both arms (e.g., initiation of Drug A vs. initiation of Drug B).

- Assignment Procedure: Specify how patients would be assigned to either treatment at random.

- Time Zero: The start of follow-up, defined as the date of meeting all eligibility criteria and being assigned a treatment strategy [27].

- Outcomes: Define the primary outcome (e.g., overall survival, hospitalization) and secondary outcomes, including how and when they are measured.

- Causal Contrast: State whether the intention-to-treat or per-protocol effect is the target of emulation [27].

2. Observational Study Emulation: The second step is to apply this protocol to the observational data [29].

- Eligibility & Cohort Creation: Apply the pre-specified eligibility criteria to the RWD source to create the study cohort.

- Define Time Zero: For each patient, establish a valid "time-zero" analogous to the point of randomization in the target trial [27] [32].

- Handle Treatment Assignment: Since treatment is not randomized, use methods like propensity score matching or inverse probability of treatment weighting to create a balanced sample where the treatment groups are comparable with respect to measured baseline covariates [30].

- Follow-Up: Begin follow-up at "time-zero" and continue until the earliest of: outcome occurrence, end of study period, loss to follow-up, or a protocol-specified censoring event (e.g., treatment discontinuation for per-protocol analysis).

- Outcome Assessment: Identify the outcome(s) based on the pre-specified definition within the follow-up period.

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze the data based on the pre-specified plan. For time-to-event outcomes, use Cox proportional hazards models. Report hazard ratios and confidence intervals.

The workflow for this protocol, from conception to result, is summarized in the diagram below.

Quantitative Validation: TTE vs. RCT Findings

A critical step in validating the TTE methodology is to benchmark its results against existing RCTs. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from such comparative studies, directly supporting the thesis on RWE validation.

Table 1: Empirical Validation of TTE Against RCT Gold Standards

| Disease Area / Study | Number of Emulations / RCTs | Key Metric | Concordance Rate | Identified Reasons for Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic Breast Cancer [31] | 8 RCTs emulated | Overall Survival (Hazard Ratio) | 7 out of 8 emulations showed consistent effect sizes | Residual confounders; shifts in prescription practices post-approval |

| Surgical & Non-Surgical Populations [27] | 32 clinical trials emulated (RCT-DUPLICATE) | Various efficacy and safety outcomes | High rate of replication for a selected subset | Data quality; inability to capture all trial variables; residual confounding |

| General Review [30] | Multiple meta-analyses | Various treatment effects | ~82% agreement (approx. 18% contradiction) | Primarily due to design flaws and unaddressed confounding in observational studies |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for TTE

This section lists the key methodological components and data elements required to successfully implement a Target Trial Emulation.

Table 2: Key "Research Reagents" for Target Trial Emulation

| Item / Component | Category | Function & Importance in TTE |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RWD Source | Data | Foundation of the emulation. Requires completeness, accuracy, and longitudinal follow-up. Examples: EHRs, claims databases, quality registries [27] [30]. |

| Pre-specified Protocol | Methodology | The blueprint. Forces explicit declaration of eligibility, treatment strategies, time-zero, outcomes, and analysis plan before analysis begins, reducing bias [29] [32]. |

| "Time-Zero" Definition | Methodology | The anchor. Clearly defines the start of follow-up for all participants, analogous to randomization in an RCT. Critical for avoiding immortal time bias [27] [32]. |

| Confounding Adjustment Methods | Analytical Tool | Mimics randomization. Techniques like Propensity Score Matching/Weighting are used to balance baseline covariates between treatment groups, addressing measured confounding [30]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Framework | Analytical Tool | Assesses robustness. Used to quantify how sensitive the results are to potential unmeasured confounding and other biases [30]. |

| TUG-1375 | TUG-1375, MF:C22H19ClN2O4S, MW:442.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tug-469 | Tug-469, CAS:1236109-67-3, MF:C23H23NO2, MW:345.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The diagram below illustrates how these components interact to address common biases in observational studies.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My propensity score matched sample has significantly reduced sample size. What should I check? This is commonly caused by poor overlap between treatment and control groups or an overly restrictive caliper. First, examine the propensity score distributions using density plots to assess overlap. If substantial regions lack common support, consider using matching methods that preserve more data, such as full matching or optimal matching. Using a machine learning approach like gradient boosting for propensity score estimation may also improve the overlap by better modeling complex relationships [33].

Q2: How can I validate that my matched groups are sufficiently balanced?

Balance should be assessed using Standardized Mean Differences (SMD) for all covariates, where SMD < 0.1 indicates good balance. Generate visual diagnostics like Love plots to display covariate balance before and after matching. Additionally, conduct formal statistical tests comparing covariate distributions between groups post-matching; p-values > 0.05 suggest successful balancing. The cobalt package in R provides specialized tools for comprehensive balance evaluation [33] [34].

Q3: My observational study results differ from RCT findings. What could explain this? Differences can arise from several sources. First, assess whether you have adequately controlled for all key confounders; unmeasured confounding is a common limitation. Use sensitivity analyses like Rosenbaum bounds to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away your results. Also consider differences in patient populations, treatment protocols, or outcome definitions between the real-world data and RCT context [5] [35].

Q4: When should I use machine learning instead of logistic regression for propensity scores? Machine learning methods are particularly beneficial when dealing with high-dimensional data (many covariates), complex non-linear relationships, or interaction effects. Gradient boosting and random forests can automatically detect these patterns without manual specification. However, ensure you use appropriate cross-validation to prevent overfitting, and remember that ML models may introduce additional complexity in variance estimation [33] [36].

Q5: How do I handle missing data in covariates when estimating propensity scores? Multiple imputation is generally recommended over complete-case analysis. After creating multiply imputed datasets, estimate propensity scores within each imputed dataset, then match within each dataset or use the averaged propensity score. Alternatively, include missingness indicators as additional covariates in the propensity model, though this approach requires careful consideration of the missingness mechanism [37].

Troubleshooting Common Technical Issues

Issue: Poor Covariate Balance After Matching

- Potential Causes: Inadequate propensity score model specification, insufficient overlap, or inappropriate matching method.

- Solutions:

- Revise your propensity score model: Add interaction terms or use more flexible machine learning methods if relationships are non-linear [33].

- Try different matching techniques: Switch from nearest-neighbor to full matching or optimal matching, which often yield better balance [33].

- Adjust caliper width: Slightly increase the caliper, but be cautious not to lose too many observations [33].

- Check for important omitted covariates: Revisit your causal diagram to ensure all relevant confounders are included [5].

Issue: Large Variance in Treatment Effect Estimates

- Potential Causes: Small effective sample size after matching, poor match quality, or heterogeneous treatment effects.

- Solutions:

- Use matching methods that retain more data: Full matching typically preserves more units than 1:1 matching [33].

- Incorporate machine learning for effect estimation: Implement Causal Forests to model and estimate heterogeneous treatment effects, which can provide more precise subgroup estimates [36] [35].

- Check for effect modification: Conduct subgroup analyses to identify sources of heterogeneity [36].

Issue: Computational Performance with Large Datasets

- Potential Causes: Inefficient matching algorithms or complex machine learning models.

- Solutions:

- Implement in-database analytics: Use SQL-based machine learning extensions like Adobe Experience Platform's Data Distiller for large-scale data without moving it [38].

- Optimize R code: Use data.table or dplyr packages for data manipulation, and consider parallel processing for complex matching [33].

- Sample strategically: For initial method development, work with a random sample before applying to the full dataset [38].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Propensity Score Matching Protocol

The following workflow outlines the key stages of a robust propensity score matching analysis:

Phase 1: Data Preparation and Covariate Selection

- Clean data: Handle missing values, outliers, and ensure consistency [33].

- Select covariates: Include variables that influence both treatment assignment and outcome (confounders). Avoid including post-treatment variables or mediators [33].

- Create analytical dataset: Transform variables as needed and encode categorical variables appropriately [33].

Phase 2: Propensity Score Estimation

- Choose estimation method:

- Specify model: Treatment ~ Covariate1 + Covariate2 + ... + CovariateN [33].

- Extract propensity scores: Predicted probabilities of treatment assignment for each subject [33].

Phase 3: Pre-Matching Diagnostics

- Assess overlap: Plot density distributions of propensity scores by treatment group [33].

- Check common support: Identify regions where both groups have substantial density [33].

- Evaluate initial balance: Calculate SMDs for all covariates before matching [33].

Phase 4: Execute Matching

- Select matching method:

- Set caliper width: Typically 0.2 standard deviations of the logit propensity score [33].

- Implement matching: Use established packages like

MatchItin R [33].

Phase 5: Post-Matching Diagnostics

- Assess balance: Recalculate SMDs for all covariates in matched sample [33] [34].

- Visualize results: Create balance plots (Love plots) to display improvement [33].

- Report matching efficiency: Document number of units matched, discarded, and effective sample size [33].

Phase 6: Treatment Effect Estimation

- Analyze matched data: Use appropriate methods for matched data (paired t-tests, conditional regression) [33].

- Account for matching design: Use robust variance estimators or bootstrap methods [33].

- Conduct sensitivity analysis: Assess robustness to unmeasured confounding using Rosenbaum bounds or E-values [36].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Causal Inference Protocol

Implementation Steps for Causal Forest Analysis:

Data Preparation

Model Specification

Model Training

Treatment Effect Estimation

Heterogeneity Assessment

Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

Comparison of Propensity Score Estimation Methods

Table 1: Performance characteristics of different propensity score estimation approaches

| Method | Best Use Case | Advantages | Limitations | Balance Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | Low-dimensional confounder sets, linear relationships | Interpretable, simple implementation, established practice | Misses complex interactions, prone to model misspecification | Good with correct specification |

| Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | High-dimensional data, non-linear relationships | Automatic feature selection, handles complex patterns | Computational intensity, risk of overfitting, less interpretable | Superior in high-dimensional settings [33] |

| Random Forests | Complex relationships, interaction effects | Robust to outliers, handles mixed data types | Can be computationally expensive | Good with complex dependencies |

| Causal Forests | Heterogeneous treatment effect estimation | Specifically designed for causal inference, "honest" estimation | Complex implementation, requires careful tuning | Excellent for heterogeneous effects [36] |

Balance Diagnostics Thresholds

Table 2: Key metrics and thresholds for evaluating matching quality

| Diagnostic Measure | Target Threshold | Interpretation | Tools/Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | < 0.1 | Indicates adequate balance for that covariate | cobalt package, tableone package [33] |

| Variance Ratio | 0.8 - 1.25 | Similar spread of covariate values between groups | cobalt package [33] |

| Kolmorogov-Smirnov Statistic | > 0.05 | Similar distribution shapes between groups | cobalt package [33] |

| Effective Sample Size | > 70% of original | Indicates matching efficiency | MatchIt package [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Software and Packages

Table 3: Key software tools for propensity score and machine learning analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Key Features | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatchIt (R) | Propensity score matching | Multiple matching methods, comprehensive diagnostics | matchit(treatment ~ covariates, data, method="nearest") [33] |

| cobalt (R) | Balance assessment | Love plots, multiple balance statistics, publication-ready output | bal.plot(matched_data, var.name = "covariate") [33] |

| grf (R) | Causal forest implementation | Honest estimation, confidence intervals, heterogeneity detection | causal_forest(X, Y, W) where W is treatment [36] |

| Data Distiller SQL ML | Large-scale in-database analytics | SQL-based machine learning, no data movement required | CREATE MODEL propensity_model PREDICT treatment USING covariates [38] |

| Scikit-learn (Python) | Machine learning for PS estimation | Multiple algorithms, hyperparameter tuning | GradientBoostingClassifier().fit(X, y) |

| V-9302 | V-9302, CAS:1855871-76-9, MF:C34H38N2O4, MW:538.69 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Vidupiprant | Vidupiprant, CAS:1169483-24-2, MF:C28H27Cl2FN2O6S, MW:609.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Methodological Frameworks

Table 4: Analytical frameworks for RWE validation against RCTs

| Framework | Primary Application | Key Components | Regulatory Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Trial Emulation | Designing observational studies to mimic RCTs | Explicit protocol, eligibility criteria, treatment strategies | Emerging acceptance for specific applications [35] |

| Transportability Analysis | Generalizing RCT findings to broader populations | Selection models, inverse odds weighting | Moderate, used in regulatory discussions [35] |

| Synthetic Control Arms | Creating external controls when RCTs are infeasible | Historical data, propensity score weighting, matching | Used in regulatory approvals for specific contexts [11] [35] |

| Doubly Robust Methods | Combining outcome and treatment models | Augmented IPW, Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE) | Growing acceptance with rigorous implementation [35] |

Technical Support Center: PPRL Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common technical and methodological challenges researchers face when implementing Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage in studies that integrate real-world evidence (RWE) and randomized controlled trial (RCT) data.

FAQ 1: How Do We Balance Linkage Accuracy with Privacy Protection Strength?

Issue: A proposed PPRL method shows excellent match rates but is suspected to have lower privacy security.

Solution:

- Action: Evaluate the method using a multi-indicator framework. Relying on a single metric (like match rate alone) fails to capture the inherent trade-offs in PPRL. A comprehensive assessment must balance linkage quality, computational efficiency, and security [39].

- Method Selection: Understand that different PPRL methods prioritize these aspects differently. For instance, some third-generation methods like embedding-based linkage or secure blocking are designed to improve scalability and accuracy while maintaining privacy, moving beyond simpler, less secure hash-encoding algorithms [40].

- Evaluation Protocol: Implement a standardized evaluation. Compare your PPRL results against a "gold standard" linkage performed with unencrypted identifiers to calculate precision and recall [41]. This quantifies the accuracy cost of privacy measures.

FAQ 2: Why Do Our Linkage Results Have Low Recall, Missing True Matches?

Issue: The PPRL process is failing to link records that should be matched, leading to a low recall rate.

Solution:

- Root Cause Analysis: Check data quality in the source identifiers. Lower linkage quality is often tied to a higher percentage of missing or incorrect personally identifiable information (PII) [41]. The completeness of fields like Social Security Number (SSN) is a major factor [41].

- Refinement Strategy:

- Token Selection: Use multiple composite tokens. If one token (e.g., SSN, sex, date of birth) fails due to a missing field, another token (e.g., sex, address, name, SSN) might succeed [41].

- Algorithm Upgrade: Move from exact matching to approximate matching techniques. Methods like Bloom filters or Hash embeddings can encode data to match "Catharine" with "Katharine" by learning associations between variants, handling real-world data errors effectively [42].

- Verification: Use a subset of data with known matches to validate and tune the matching thresholds.

FAQ 3: How Can We Implement a Scalable and Secure PPRL Process for Large Datasets?

Issue: The PPRL method works on small samples but does not scale to large, database-sized volumes or raises security concerns about a centralized approach.

Solution:

- Adopt Scalable Techniques: Utilize third-generation PPRL techniques designed for large databases. These include [40]:

- Architecture Recommendation: Implement a secure enclave model. In this "eyes-off" architecture [42]:

- Two organizations encrypt their datasets.

- Data is sent to a third-party secure cloud "enclave" where it remains encrypted in memory.

- The enclave performs the linkage without human exposure and returns the encrypted results.

- This creates a "Swiss cheese" model of overlapping security layers (algorithms, encryption, secure cloud technology) to protect sensitive information [42].

FAQ 4: What Are the Regulatory Considerations When Using PPRL for Pharmacovigilance?

Issue: Uncertainty about how to use linked RWD and RCT data for drug safety reporting in a regulatory-compliant manner.

Solution:

- Guidance Adherence: Follow FDA and other international regulatory body guidance that recognizes the need for data linkage techniques and privacy-preserving methods [43]. The FDA's framework emphasizes the relevance, reliability, and traceability of RWD [43].

- Best Practices:

- Establish Clear Protocols: Develop pre-planned analysis protocols for safety signal detection and risk management using linked data [43].

- Ensure Legal Compliance: Use PPRL techniques, like hashing, that meet established de-identification standards such as those under the HIPAA Privacy Rule [41] [43].

- Engage Early: Seek early regulatory engagement to align on the use of linked RWD in your development program [43].

Quantitative Performance Data for PPRL Methods

The tables below summarize empirical data on PPRL performance, providing a basis for comparing methods and setting realistic expectations for your experiments.

Table 1: PPRL Performance Against Gold Standard Linkage

This table compares the performance of different PPRL approaches against a traditional linkage method using unencrypted identifiers, based on a study linking the National Hospital Care Survey (NHCS) to the National Death Index (NDI) [41].

| Linkage Method | Match Rate | Precision | Recall | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard (Plain Text) | 5.1% | (Baseline) | (Baseline) | Uses unencrypted PII; deterministic and probabilistic techniques [41]. |

| Initial PPRL Approach | 5.4% | 93.8% | 98.7% | Relies on hashed tokens; performance varies with token selection [41]. |

| Refined PPRL Approach | 5.0% | 98.9% | 97.8% | Optimized token selection; achieves a balance of high precision and recall [41]. |

Table 2: Performance of Specific PPRL Techniques on Standardized Datasets

This table shows the performance of specific PPRL toolkits and algorithms on standardized datasets, demonstrating the high accuracy achievable with modern methods [42].

| PPRL Method / Toolkit | Dataset | Recall | Precision | Key Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONS PPRL Toolkit | FEBRL 4 (5,000 records) | 99.3% | 100% | Bloom filter method [42]. |

| Splink (Published Demo) | FEBRL 4 (5,000 records) | 99.2% | 100% | Probabilistic linkage model [42]. |

| Hash Embeddings | (Theoretical Application) | (High) | (High) | Pretrained model learns associations between data variants (e.g., "Catharine" and "Katharine") [42]. |

Experimental Protocols for PPRL Implementation and Validation

Protocol 1: Validating a PPRL Method Against a Gold Standard

This protocol is based on a real-world study conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics to assess PPRL quality before implementation with new data sources [41].

Objective: To assess the precision and recall of a new PPRL technique by comparing its results to a previously established linkage of the same datasets performed with unencrypted identifiers.

Materials:

- Two datasets previously linked using traditional methods (the "gold standard").

- PPRL software (e.g., Datavant, ONS PPRL Toolkit).

- Data processing software (e.g., SAS, R, Python).

Methodology:

- Hashing/Tokenization: Transform the PII (names, addresses, dates of birth) in both datasets into encrypted codes or tokens using the selected PPRL software. Create multiple tokens from different combinations of PII (e.g., sex+DOB+SSN; sex+address+name+SSN) [41].

- Linking: Perform the record linkage within the PPRL environment using the generated tokens.

- Comparison: Compare the results from the PPRL linkage to the gold standard linkage.

- Calculation:

- Precision: Calculate the proportion of records linked by PPRL that are true matches in the gold standard. (Precision = True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives)).

- Recall: Calculate the proportion of true matches in the gold standard that were correctly identified by the PPRL method. (Recall = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)) [41].

- Impact Assessment: Analyze the impact of PPRL on secondary data analysis (e.g., compare match rates and mortality rates across the gold standard and PPRL methods) to ensure scientific conclusions are not affected [41].

Protocol 2: Implementing an "Eyes-Off" Secure Enclave Linkage

This protocol outlines the steps for a secure, scalable linkage process as demonstrated by the ONS PPRL toolkit [42].

Objective: To link two sensitive datasets from different organizations without either organization sharing personal information or accessing the other's raw data.

Materials:

- Two datasets from different organizations (Data Owner A and Data Owner B).

- A PPRL Python package (e.g., ONS toolkit implementing Hash embeddings).

- Access to a secure cloud environment supporting confidential computing (e.g., Google Cloud Confidential Space).

Methodology:

- Environment Setup: Provision a secure enclave virtual machine in the cloud. This environment will keep data encrypted even during processing [42].

- Data Preparation and Encryption:

- Secure Transfer and Attestation:

- The encrypted datasets are sent to the secure enclave.

- The enclave sends an attestation to each key manager, proving it is running in a trusted, secure state. Upon verification, the key managers grant the enclave access to the decryption keys. Data remains protected by the enclave's in-memory encryption [42].

- Matching: The PPRL algorithm performs the linkage within the secure enclave, comparing the encrypted representations.

- Result Return: The enclave encrypts the final set of matched records and sends it back to both organizations [42].

Workflow and Architecture Diagrams

PPRL Secure Enclave Workflow

PPRL Technique Evolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential PPRL Research Reagents

Table 3: Key PPRL Solutions and Their Functions

This table catalogs essential methodological solutions and software tools used in the field of Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage.

| Research Reagent Solution | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hashing / Tokenization | Cryptographic Technique | Converts PII (name, DOB) into unique, irreversible encrypted codes to create tokens for matching without revealing original values [41]. | Foundational step for most PPRL methods; meets HIPAA de-identification standards [41]. |

| Bloom Filters | Data Structure | Represents PII as a fixed-length bit array, allowing for efficient approximate matching of strings (e.g., handling typographical errors) [40] [42]. | A widely used method for encoding data in PPRL; balance of privacy and linkage accuracy. |

| Hash Embeddings | Machine Learning Model | An extension of Bloom filters; a pre-trained model that learns associations between data variants (e.g., "Catharine" and "Kitty") to improve matching performance [42]. | Used for advanced linkage on "dirty" data with many variations; requires a training corpus. |

| Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) | Cryptographic Protocol | Enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function over their inputs while keeping those inputs private [40]. | For complex, secure computations where no single party should see the others' data. |

| Secure Enclave / Confidential Computing | Hardware/Cloud Architecture | A secure area in a cloud server where data is processed in encrypted memory, preventing access even by the cloud provider [42]. | Enables "eyes-off" data linkage; used as a trusted third party in the Swiss cheese security model [42]. |

| Modified CRITIC Method | Evaluation Framework | A comprehensive evaluation method using mathematical statistics to assign objective weights to multiple PPRL performance indicators (quality, efficiency, security) [39]. | For objectively comparing and selecting the optimal PPRL method for a specific scenario. |

| Vilaprisan | Vilaprisan (BAY 1002670) | Vilaprisan is a potent selective progesterone receptor modulator (SPRM) for uterine fibroid and endometriosis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a Synthetic Control Arm (SCA)? A Synthetic Control Arm (SCA) is an external control group constructed using statistical methods applied to one or more external data sources, such as results from previous clinical trials or Real-World Data (RWD). It serves as a comparator to the investigational treatment arm in a clinical study when a concurrent control group is impractical or unethical [44] [45].

In what situations are SCAs most beneficial? SCAs are particularly beneficial in scenarios where traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) face significant challenges [44] [46] [47]:

- Rare diseases: Where patient populations are small and recruiting for a control arm is difficult.

- Oncology: Especially for rare molecular subtypes where randomization is infeasible.

- Life-threatening conditions: Where ethical concerns exist about assigning patients to a placebo or standard-of-care arm.

- Unmet medical need: When there is no effective standard treatment, and a state of clinical equipoise does not exist.

What are the primary data sources for constructing an SCA? SCAs are primarily built from two types of data [44] [47]:

- Historical Clinical Trial Data: Data from previous clinical trials, which is typically highly standardized and of good quality but may suffer from recruitment biases.

- Real-World Data (RWD): Data derived from electronic health records (EHRs), insurance claims, and patient registries. RWD offers a broader patient representation but often requires extensive processing due to issues with missing data, formatting, and standardization.

What do regulators say about using SCAs? Major regulatory agencies, including the FDA and EMA, recognize the value of SCAs in certain circumstances [44] [47]. They emphasize that their use should be justified on a case-by-case basis. Key regulatory expectations include:

- Early engagement: Sponsors are strongly encouraged to engage with regulators early in the protocol development process.

- Robust methodology: The statistical methods and data sources must be clearly defined and justified.

- Bias mitigation: The study design must proactively address potential sources of bias, such as selection bias and confounding.

What are the biggest advantages of using an SCA?

- Ethical Improvement: Reduces the number of patients exposed to a potential placebo or inferior standard of care [44] [47].

- Improved Feasibility: Accelerates patient recruitment and trial completion, especially in rare diseases [44] [45].

- Cost and Time Efficiency: Can be more cost-effective and time-efficient by avoiding the costs associated with recruiting and managing a concurrent control arm [44].

What are the common limitations and risks?

- Data Quality Dependency: The validity of an SCA is entirely dependent on the quality, completeness, and relevance of the underlying data [44] [48].

- Potential for Bias: SCAs are susceptible to biases, particularly selection bias and unmeasured confounding, since patients are not randomized [44] [46].

- Regulatory Scrutiny: Regulatory agencies may approach SCAs with caution, requiring robust justification and validation of the methodology [44].

Troubleshooting Common SCA Challenges

Challenge 1: Data Quality and Relevance

Problem: The real-world or historical data is fragmented, has missing key variables (like ECOG Performance Status), or does not perfectly reflect the current standard of care or patient population [44] [48].

Solutions:

- Conduct Thorough Data Source Evaluation: Before selection, assess data sources for provenance, completeness, and how well they represent the target population. Document all accessed data sources and justifications for inclusion or exclusion [44] [49].

- Implement Robust Data Pre-processing: Use rigorous data cleaning and harmonization techniques. For missing data, employ methods like multiple imputation and conduct sensitivity analyses (e.g., "tipping point" analyses) to test how the results hold up under different assumptions about the missingness [50].

- Engage Subject Matter Experts: Involve clinicians and disease area experts to validate that the data sources and the resulting SCA are clinically plausible and reflect current medical practice [44] [49].

Challenge 2: Achieving an Adequate Match

Problem: The synthetic control group does not adequately balance the baseline characteristics of the treatment group, leading to biased effect estimates.

Solutions:

- Use Advanced Statistical Matching Techniques: Go beyond simple matching. Commonly used methods include:

- Propensity Score Matching (PSM): Estimates the probability of being in the treatment group given observed covariates and matches treated and control units with similar scores [47].

- Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW): Uses propensity scores to create a weighted population where the distribution of measured covariates is independent of treatment assignment [50].

- Validate the Match Quantitatively: After matching, check the balance of covariates between groups using standardized mean differences (SMD). A common threshold for good balance is SMD < 0.1 [50].