Beyond the Gold Standard: A Modern Framework for Evaluating Pharmaceutical Effectiveness Through RCTs and Observational Studies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolving roles of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and observational studies in evaluating pharmaceutical effectiveness.

Beyond the Gold Standard: A Modern Framework for Evaluating Pharmaceutical Effectiveness Through RCTs and Observational Studies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolving roles of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and observational studies in evaluating pharmaceutical effectiveness. It explores the foundational principles of both methodologies, contrasting their traditional strengths and limitations. The content delves into modern innovations such as adaptive platform trials and causal inference methods that are blurring the methodological lines. Through practical applications and case studies, including lessons from COVID-19 drug repurposing, it offers guidance for selecting appropriate designs and mitigating biases. The article synthesizes evidence on how these approaches can be integrated to generate robust, real-world evidence for regulatory and clinical decision-making, ultimately advocating for a complementary rather than competitive framework in pharmaceutical research.

Understanding the Pillars of Evidence: Core Principles of RCTs and Observational Studies

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical research, two methodological paradigms form the cornerstone of evidence generation: the experimental framework of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and the observational nature of Real-World Observational Studies. The former is widely regarded as the "gold standard" for evaluating the efficacy and safety of an intervention under ideal conditions, while the latter provides critical insights into the effectiveness of these interventions in routine clinical practice [1]. Understanding the distinct roles, advantages, and limitations of each approach is fundamental for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who must navigate the complex evidence landscape for regulatory approval and clinical decision-making. This guide provides a structured comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their application in assessing pharmaceutical products.

The fundamental distinction lies in investigator intervention. RCTs are interventional studies where investigators actively assign treatments to participants, while observational studies are non-interventional, meaning investigators merely observe and analyze treatments and outcomes as they occur in normal clinical practice without attempting to influence them [1]. This core difference drives all subsequent methodological variations and determines the types of conclusions each approach can support.

Methodological Foundations and Key Characteristics

Defining the Core Paradigms

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are prospective studies in which participants are randomly assigned to receive one or more interventions (including control treatments such as placebo or standard of care) [2]. The key components of this definition are:

- Prospective Design: The study is planned and participants are enrolled and followed forward in time.

- Random Assignment: A computer or other random process determines treatment allocation, preventing systematic bias in group assignment.

- Controlled Comparison: Outcomes in the investigational group are compared against a control group, which may receive a placebo, no treatment, or the current standard of care [2].

Observational Studies encompass a range of designs where investigators assess the relationship between interventions or exposures and outcomes without assigning treatments. Participants receive interventions as part of their routine medical care, and the investigator observes and analyzes what happens naturally [3] [1]. The major observational designs include:

- Cohort Studies: Subjects are selected based on their exposure status and followed to determine outcome incidence.

- Case-Control Studies: Subjects are selected based on their outcome status, with investigators then looking back to assess prior exposures.

- Cross-Sectional Studies: Exposure and outcome are assessed at the same point in time [3].

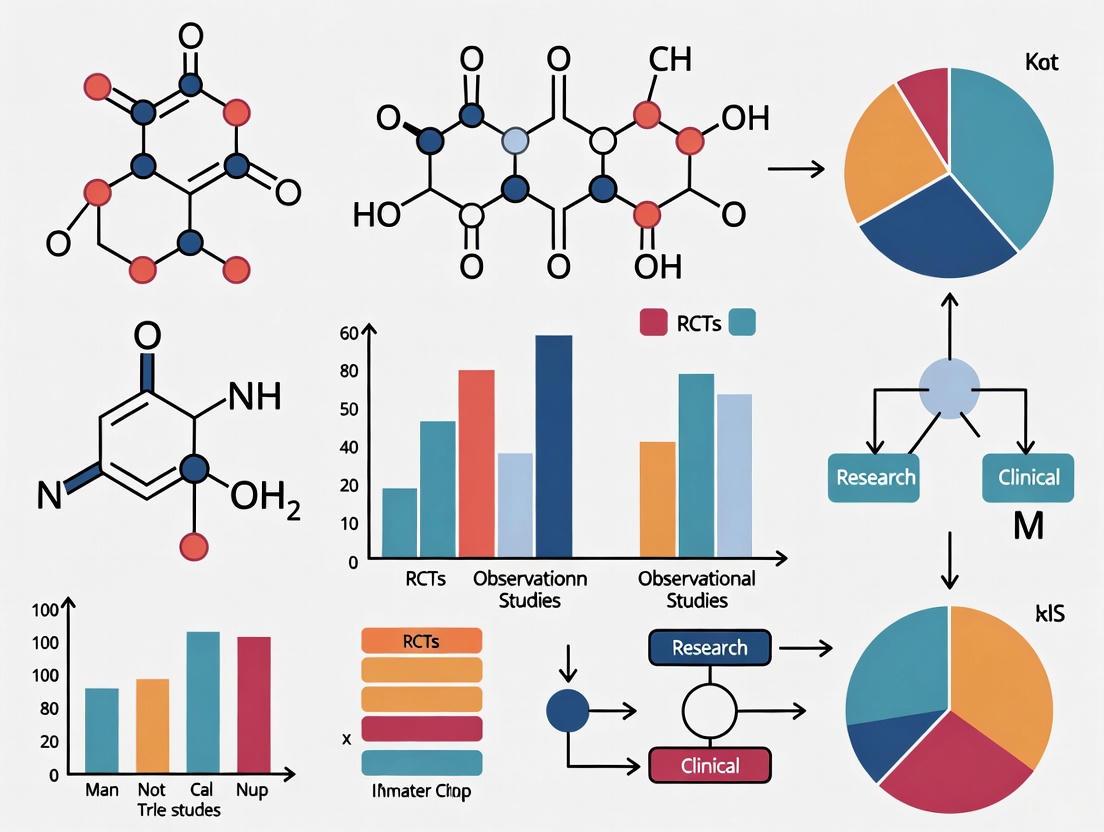

Visualizing the Research Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental pathways and decision points that differentiate RCTs from observational studies in pharmaceutical research.

Comparative Analysis: RCTs vs. Observational Studies

Structured Comparison of Study Characteristics

The table below provides a detailed, side-by-side comparison of the fundamental characteristics distinguishing RCTs from observational studies.

| Characteristic | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Observational Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Design | Experimental, interventional | Non-interventional, observational |

| Participant Selection | Highly selective based on strict inclusion/exclusion criteria [1] | Broad, real-world populations from clinical practice [1] |

| Group Assignment | Random allocation by computer/system [2] | Naturally formed through clinical decisions/patient choice [3] |

| Control Group | Always present (placebo, standard of care) [2] | Constructed statistically from comparable untreated individuals |

| Blinding | Often single, double, or triple-blinded [1] | Generally not possible due to observational nature |

| Intervention | Strictly protocolized and standardized | Varies according to routine clinical practice |

| Primary Objective | Establish efficacy (effect under ideal conditions) and safety for regulatory approval [1] [2] | Establish effectiveness (effect in routine practice) and monitor long-term/rare safety [1] |

| Key Advantage | High internal validity; minimizes confounding through randomization [4] | High external validity/generalizability; assesses long-term outcomes and rare events [3] |

| Primary Limitation | Limited generalizability to broader populations; high cost and complexity [4] [2] | Susceptible to confounding and bias; cannot prove causation [3] [5] |

| Typical Context | Pre-marketing drug development (Phases 1-3) [1] | Post-marketing surveillance (Phase 4), comparative effectiveness [1] |

Quantitative Data Comparison

The table below summarizes key quantitative differences between these research approaches, highlighting how these differences impact their application and interpretation.

| Quantitative Metric | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Observational Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sample Size | ~100-3,000 participants (Phases 1-3) [1] | Can include thousands to millions of participants using databases/registries [1] |

| Study Duration | Weeks to months (Phase 2/3); up to several years for long-term outcomes [4] [1] | Can extend for many years to assess long-term outcomes and safety [3] |

| Patient Population | Narrow, homogeneous population; may exclude elderly, comorbidities, polypharmacy [4] [1] | Heterogeneous, representative of real-world patients including those excluded from RCTs [1] |

| Cost & Resource Requirements | Very high (monitoring, site fees, drug supply, lengthy timelines) [6] [2] | Relatively lower cost, especially when using existing databases/registries [1] |

| Ability to Detect Rare Adverse Events | Limited by sample size and duration; underpowered for rare events [4] | Superior for detecting rare or long-term adverse events due to large sample sizes [3] [1] |

| Regulatory Status for Approval | Required as primary evidence for drug approval (pivotal trials) [1] | Supportive evidence for safety; generally not sufficient alone for initial approval [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for a Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Trial

A typical Phase 3 RCT follows a rigorous, predefined protocol to ensure validity and reliability:

Protocol Development: A detailed study protocol is created specifying objectives, design, methodology, statistical considerations, and organization. This includes precise eligibility criteria for participants to create a homogeneous study population [1].

Randomization and Blinding: After screening and informed consent, participants are randomly assigned to study groups using a computer-generated randomization sequence. Allocation concealment prevents researchers from influencing which group participants enter. Studies are often double-blinded, meaning neither participants nor investigators know treatment assignments [1] [2].

Intervention and Follow-up: The investigational drug, placebo, or active comparator is administered according to a fixed schedule and dosage. Participants are followed prospectively at predefined intervals with standardized assessments, including efficacy endpoints, safety monitoring (e.g., adverse events, lab tests), and adherence checks [1].

Endpoint Adjudication: Clinical endpoints are often reviewed by an independent endpoint adjudication committee blinded to treatment assignment to minimize bias in outcome assessment.

Statistical Analysis: Primary analysis follows the Intent-to-Treat (ITT) principle, analyzing participants according to their randomized group regardless of adherence. Statistical methods like ANOVA, ANCOVA, or mixed models are used to compare outcomes between groups, with a predefined primary endpoint and statistical power [1].

Protocol for a Cohort Observational Study

A typical protocol for a prospective cohort observational study involves:

Data Source Selection: Researchers identify appropriate real-world data sources, such as electronic health records, insurance claims databases, disease registries, or pharmacy databases that capture the exposures and outcomes of interest [1].

Cohort Definition: The study population is defined based on exposure status (e.g., users of a specific drug vs. users of a different drug) or based on a specific diagnosis. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied, but are typically broader than in RCTs to reflect real-world practice [3] [1].

Baseline Assessment and Confounder Measurement: Characteristics are measured at baseline for all cohort members, including potential confounders (e.g., age, sex, disease severity, comorbidities, concomitant medications). This allows for statistical adjustment in analyses [3].

Follow-up and Outcome Measurement: Participants are followed for the development of predefined outcomes, which are identified using diagnostic codes, pharmacy records, or mortality data. The follow-up is observational, without intervention in clinical care [3].

Statistical Analysis to Control Bias: Techniques like propensity score matching or regression adjustment are used to create balanced comparison groups and control for measured confounding. Unlike RCTs, observational studies cannot control for unmeasured confounders, which remains a key limitation [3] [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below details key methodological components and tools essential for conducting rigorous RCTs and observational studies in pharmaceutical research.

| Research Component | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization Sequence Generator | Generates unpredictable allocation sequences to eliminate selection bias | Critical for RCTs; ensures groups are comparable for known and unknown factors [2] |

| Blinding/Masking Procedures | Conceals treatment assignment from participants, investigators, and outcome assessors | Used in RCTs to prevent performance and detection bias [1] |

| Standardized Treatment Protocol | Ensures uniform intervention administration across all study participants | Essential for RCT internal validity; minimizes variation in treatment delivery [1] |

| Propensity Score Methods | Statistical method to balance measured covariates between exposed and unexposed groups | Used in observational studies to simulate randomization and reduce confounding [1] |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Systems | Provides comprehensive longitudinal data on patient care, outcomes, and covariates | Primary data source for many observational studies; enables large-scale population research [1] |

| Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) | Independent expert committee that monitors patient safety and treatment efficacy data | Required for RCTs; periodically reviews unblinded data to ensure participant safety [1] |

| Case Report Forms (CRFs) | Standardized data collection instruments for capturing research data | Used in both RCTs (prospective collection) and some prospective observational studies |

| Claims and Pharmacy Databases | Administrative data capturing prescriptions, procedures, and diagnoses for billing | Valuable data source for pharmacoepidemiology studies assessing drug utilization and safety [3] |

Current Landscape and Future Directions

The contemporary clinical research landscape recognizes the complementary value of both RCTs and observational studies rather than viewing them as hierarchical [1] [5]. While RCTs remain foundational for regulatory decisions due to their high internal validity, observational studies provide critical information about how drugs perform in diverse patient populations and over longer timeframes than typically feasible in trials [3] [1].

Recent trends include the emergence of Pragmatic Clinical Trials (PrCTs) that incorporate elements of both designs by maintaining randomization while operating in real-world clinical settings [1]. Additionally, current policy shifts, including NIH grant terminations and legislative changes, are disproportionately affecting certain types of research, with one analysis indicating approximately 3.5% of NIH-funded clinical trials (n=383) experiencing grant terminations, disproportionately affecting prevention trials (8.4%) and infectious disease research (14.4%) [7]. These disruptions highlight the fragility of clinical trial infrastructure and may inadvertently increase reliance on observational designs for some research questions.

In conclusion, the choice between RCTs and observational studies is not a matter of selecting a superior methodology but rather of matching the appropriate design to the specific research question at hand. For establishing causal efficacy under controlled conditions, RCTs remain indispensable. For understanding real-world effectiveness, long-term safety, and patterns of use in clinical practice, well-designed observational studies provide evidence that RCTs cannot. The most comprehensive understanding of pharmaceutical benefit-risk profiles emerges from the thoughtful integration of evidence from both paradigms.

Within the rigorous framework of evidence-based medicine, Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) occupy the highest echelon for evaluating the efficacy and safety of pharmaceutical interventions. Their premier status is not merely conventional but is fundamentally rooted in their unparalleled ability to ensure high internal validity through methodological safeguards against bias. In the context of comparative effectiveness research, where observational studies derived from real-world data (RWD) offer complementary strengths, RCTs provide the critical anchor of causal certainty. The core of this advantage lies in the deliberate and systematic process of randomization, which effectively neutralizes confounding—a pervasive challenge in observational research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the mechanistic operation of randomization is essential for interpreting clinical evidence and designing studies that yield unbiased estimates of treatment effects. This guide objectively examines the experimental data and methodological protocols that underscore the RCT's advantage, providing a comparative analysis with observational studies to inform strategic decisions in pharmaceutical research and development.

Foundational Principles: Internal Validity and Confounding

The Pillar of Internal Validity

Internal validity refers to the extent to which the observed effect in a study can be accurately attributed to the intervention being tested, rather than to other, alternative explanations [8]. It is the cornerstone of causal inference. In an ideal study with perfect internal validity, a measured difference in outcomes between treatment and control groups is caused only by the difference in the treatments received. RCTs are explicitly designed to achieve this through random allocation, which balances both known and unknown prognostic factors across study arms, thereby creating comparable groups from the outset [9] [10].

The Problem of Confounding

Confounding is a situation in which a non-causal association between an exposure (e.g., a drug) and an outcome is created or distorted by a third variable, known as a confounder [9]. A confounder must meet three criteria:

- It must be a cause (or a proxy for a cause) of the outcome.

- It must be associated with the exposure.

- It must not be a consequence of the exposure.

- Example from Observational Research: Consider an observational study investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on lung cancer. Smoking is a potent confounder in this scenario, as it is a known cause of lung cancer and is also associated with alcohol consumption. A naive analysis that fails to adjust for smoking would likely misleadingly suggest that alcohol causes lung cancer [9].

Observational studies must employ sophisticated statistical methods post-hoc to adjust for measured confounders, but they remain vulnerable to unmeasured or unknown confounding. Randomization in RCTs is the primary methodological defense against this threat.

The RCT Mechanism: Experimental Protocol for Randomization

The following workflow details the standard experimental protocol for randomizing participants in a parallel-group RCT, the most common design in pharmaceutical research.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for participant randomization in RCTs.

Detailed Methodological Steps

- Eligibility Screening & Informed Consent: Potential participants are screened against pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to create a homogenous study population. Eligible individuals provide informed consent before any study procedures [10].

- Baseline Assessment: Comprehensive data on demographic and clinical characteristics are collected. These variables can later be used to verify the success of randomization and may inform stratified randomization in small studies to ensure balance on key prognostic factors [10].

- Random Allocation Sequence Generation: A computer-generated random sequence is produced to determine the group assignment (e.g., intervention or control) for each participant. This is the core of the RCT methodology [8] [10].

- Allocation Concealment: The random sequence is concealed from the investigators enrolling participants (e.g., via a central, automated system). This prevents selection bias by ensuring the researcher cannot influence which assignment the next participant will receive [8].

- Intervention Administration: Participants receive their allocated intervention. Blinding (or masking) is often implemented, where participants, clinicians, and outcome assessors are unaware of the assignment to further prevent performance and detection bias [8].

- Follow-up and Outcome Assessment: Participants are followed for a pre-specified period, and outcome data are collected systematically.

- Data Analysis: Outcomes are compared between the groups. The analysis is typically conducted according to the Intention-to-Treat (ITT) principle, which analyzes participants in the groups to which they were originally randomized, preserving the benefits of randomization [11].

Quantitative Comparison: RCTs vs. Observational Studies

Empirical evidence systematically comparing pooled results from RCTs and observational studies provides quantitative support for the RCT advantage in controlling bias.

Experimental Data on Effect Estimate Concordance

A 2021 systematic review compared relative treatment effects of pharmaceuticals from observational studies and RCTs across 30 systematic reviews and 7 therapeutic areas [12].

Table 1: Concordance of Relative Treatment Effects between Observational Studies and RCTs [12]

| Metric of Comparison | Number of Pairs Analyzed | Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Statistical Difference | 74 pairs from 29 reviews | 79.7% showed no statistically significant difference | The majority of comparisons are concordant. |

| Extreme Difference in Effect Size | 74 pairs from 29 reviews | 43.2% showed an extreme difference (ratio <0.70 or >1.43) | A substantial proportion of observational estimates meaningfully over- or under-estimated the treatment effect. |

| Significant Difference with Opposite Direction | 74 pairs from 29 reviews | 17.6% showed a significant difference with estimates in opposite directions | In a notable minority of cases, observational studies could lead to fundamentally wrong conclusions about the benefit or harm of a treatment. |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Features

The fundamental differences in design between RCTs and observational studies directly impact their susceptibility to bias and their applicability.

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of RCTs and Observational Studies [8] [13] [9]

| Feature | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Observational Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Experimental; investigator assigns intervention. | Observational; investigator observes exposure and outcome. |

| Confounding Control | Randomization balances both measured and unmeasured confounders at baseline. | Statistical adjustment (e.g., regression, propensity scores) for measured confounders only. |

| Internal Validity | High, due to randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment. | Variable and lower, highly dependent on study design, data quality, and analytical methods. |

| External Validity (Generalizability) | Can be limited due to strict eligibility criteria and artificial trial settings. | Typically higher, as studies often involve broader patient populations in real-world settings. |

| Key Strengths | Strong causal inference for efficacy; gold standard for regulatory approval of efficacy. | Insights into long-term safety, effectiveness in routine care, and rare outcomes; hypothesis-generating. |

| Key Limitations & Biases | High cost, long duration, limited generalizability, ethical/logistical constraints for some questions. | Vulnerable to unmeasured confounding, selection bias, and immortal time bias [14] [11]. |

Case Study: Immortal Time Bias – A Specific Threat to Observational Validity

Immortal Time Bias (ITB) is a pervasive methodological pitfall in observational studies that can create a spurious impression of treatment benefit [14]. It occurs when follow-up time for the treated group includes a period during which, by definition, the outcome (e.g., death) could not have occurred because the patient had not yet received the treatment.

- Mechanism: In a naive analysis comparing survival between treated and untreated patients, the period between cohort entry and treatment initiation in the treated group is misclassified as "exposed" time. Since patients must survive this period to receive treatment, this "immortal" time artificially inflates the survival probability in the treated group [14].

- Experimental Evidence: A 2025 analysis using the IMMORTOOL tool demonstrated that previously published, influential observational studies suggesting a large survival benefit for intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) were likely explained, at least in part, by immortal time bias [14]. When proper analytical methods (like treating the intervention as a time-varying exposure) were applied in benchmark studies, the protective association was substantially attenuated.

- RCT Safeguard: The RCT protocol, with its fixed time zero (randomization) and concurrent follow-up of both groups, inherently prevents this type of bias.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Analytical Solutions for Causal Inference

Table 3: Essential Methodological and Analytical Tools for Clinical Research

| Tool / Solution | Function / Definition | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Random Allocation Sequence | A computer-generated protocol that randomly assigns participants to study groups, forming the foundation of an RCT. | RCTs; ensures comparability of groups at baseline. |

| Stratified Randomization | A technique to ensure balance of specific prognostic factors (e.g., age, disease severity) across treatment groups, particularly useful in small trials. | Small RCTs (<400 participants) to improve power and balance [10]. |

| Allocation Concealment | The stringent process of hiding the allocation sequence from those enrolling participants, preventing selection bias. | RCTs; ensures randomness is not subverted. |

| Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Analysis | Analyzing all participants in the groups to which they were randomized, regardless of what treatment they actually received. | RCTs; preserves the unbiased comparison created by randomization. |

| Propensity Score Methods | A statistical method (matching, weighting, stratification) used in observational studies to adjust for measured confounders by making treated and untreated groups appear similar. | Observational studies; attempts to approximate the conditions of an RCT [9] [11]. |

| Time-Varying Exposure Analysis | A statistical technique where a patient's exposure status (e.g., treated/untreated) can change over time during follow-up. | Observational studies; the correct method to avoid immortal time bias [14]. |

| Target Trial Emulation Framework | A structured approach for designing observational studies to explicitly mimic the protocol of a hypothetical RCT (the "target trial") [11]. | Observational studies; improves causal inference by pre-specifying eligibility, treatment strategies, and follow-up. |

| (Z/E)-GW406108X | (Z/E)-GW406108X, MF:C20H11Cl2NO4, MW:400.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DP50 | DP50, MF:C58H72N8O7, MW:993.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The RCT advantage in securing internal validity and controlling for confounding through randomization remains empirically sound and methodologically uncontested. Quantitative comparisons show that while observational studies often yield similar results, they carry a measurable risk of significant and sometimes dangerously misleadingåå·® [12]. Specific biases like immortal time bias further highlight the vulnerabilities of observational data when causal claims are pursued [14] [11].

However, the evolving landscape of clinical research is not one of replacement but of integration. Observational studies using real-world data are indispensable for assessing long-term safety, effectiveness in heterogeneous populations, and clinical questions where RCTs are unethical or infeasible [13] [9] [15]. Innovations such as causal inference methods, the target trial emulation framework, and hybrid designs like registry-based RCTs are blurring the lines between methodologies, creating a more robust, convergent paradigm [9] [10]. For the pharmaceutical research professional, the optimal approach is not a rigid allegiance to a single methodology, but a critical understanding of the strengths and limitations of each, leveraging the uncontested internal validity of RCTs for establishing efficacy, while harnessing the breadth and generalizability of observational studies to complete the picture of a drug's performance in the real world.

In the landscape of clinical research, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have traditionally been regarded as the gold standard for establishing causal inference in pharmaceutical efficacy [16] [9]. However, the pursuit of real-world evidence in comparative effectiveness research has highlighted significant limitations of RCTs, particularly concerning external validity—the extent to which study findings can be generalized to other populations, settings, and real-world practice conditions [17] [18]. This guide objectively compares the performance of observational studies and RCTs, framing them not as competitors but as complementary methodologies within a comprehensive evidence generation strategy. We examine how observational studies carve a distinct niche by addressing critical questions of feasibility, ethics, and generalizability that RCTs often cannot, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Defining the Comparative Framework: Internal vs. External Validity

The choice between an RCT and an observational study design often involves a trade-off between internal validity and external validity.

- Internal Validity refers to the degree of confidence that a causal relationship is not influenced by other factors or variables. RCTs achieve high internal validity through random assignment, which balances both measured and unmeasured patient characteristics across treatment groups, thereby minimizing confounding [9].

- External Validity refers to the extent to which research findings can be generalized to other situations, people, settings, and measures [18]. It is subdivided into:

- Population Validity: The generalizability of results from the study sample to a broader target population.

- Ecological Validity: The generalizability of results to real-world situations and settings [18].

This relationship is a fundamental trade-off in clinical research. The highly controlled conditions of an RCT ensure high internal validity but can create an artificial environment that poorly reflects routine clinical practice, thus limiting external validity [16] [17]. Conversely, observational studies, which observe the effects of exposures in real-world settings without assigned interventions, are often better positioned to provide evidence with high external validity [9].

The following diagram illustrates the core trade-off and the distinct strengths of each study type in the research ecosystem.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: RCTs vs. Observational Studies

The comparative effectiveness estimates from RCTs and observational studies have been systematically evaluated. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from a 2021 systematic review of 29 prior reviews across 7 therapeutic areas, which analyzed 74 pairs of pooled relative effect estimates from RCTs and observational studies [12].

Table 1: Comparability of Relative Treatment Effects from RCTs and Observational Studies

| Comparison Metric | Findings | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Significance | No statistically significant difference in 79.7% of paired estimates. | Majority of comparisons show agreement between study designs. |

| Extreme Difference | 43.2% of pairs showed an extreme difference (ratio of relative effect estimates <0.70 or >1.43). | Notable variation exists in a substantial proportion of comparisons. |

| Opposite Directions | 17.6% of pairs showed a significant difference with estimates pointing in opposite directions. | Underlines potential for conflicting conclusions in a minority of cases. |

A specific example of observational study performance is demonstrated in a 2025 study by Li et al., which utilized Natural Language Processing (NLP) to extract data from electronic health records (EHRs) of advanced lung cancer patients [19].

Table 2: Performance of an NLP-Based Observational Study in Advanced Lung Cancer

| Performance Parameter | Result | Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Data Extraction Time | 8 hours for 333 patient records. | Extremely time-efficient compared to manual chart review. |

| Data Completeness | Minimal missing data (Smoking status: n=2; ECOG status: n=5). | High feasibility for capturing key clinical variables. |

| Identified Prognostic Factors | For NSCLC: Male gender (HR 1.44), worse ECOG (HR 1.48), liver mets (HR 2.24). For SCLC: Older age (HR 1.70), liver mets (HR 3.81). | Findings were consistent with established literature, supporting external validity. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflows

Protocol for a Modern Observational Study Using Real-World Data

The workflow for generating reliable evidence from observational data requires rigorous design to mitigate bias. The following protocol, drawing from contemporary methods, outlines key steps for a robust observational analysis [19] [9].

Table 3: Essential Protocol Steps for a Robust Observational Study

| Protocol Phase | Key Activities | Tool/Technique Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Source & Cohort | Identify a data source (e.g., EHR, registry) that captures the real-world population. Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria to define the cohort. | EHRs (e.g., Princess Margaret Cancer Centre data [19]), health insurance claims, disease registries. |

| 2. Exposure & Outcome | Clearly define the exposure (e.g., specific pharmaceutical) and the outcome of interest (efficacy or safety endpoint). | NLP extraction of unstructured clinical notes [19], ICD codes, procedure codes. |

| 3. Causal Design & Analysis | Design the study to emulate a target trial. Use statistical methods to control for measured confounding. Conduct sensitivity analyses. | Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), Propensity Score Matching, E-value calculation for unmeasured confounding [9]. |

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below, highlighting the iterative and structured approach required to ensure validity.

Protocol for a Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial

Pragmatic RCTs are designed to bridge the gap between explanatory RCTs and observational studies by testing effectiveness in routine practice conditions [20]. The key elements of their protocol are summarized below.

Table 4: Key Differentiators of a Pragmatic RCT Protocol

| Protocol Element | Pragmatic RCT Approach | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Selection | Broad, minimally restrictive eligibility criteria to reflect clinical population. | Maximize Population Validity. |

| Intervention Delivery | Flexible delivery mimicking real-world practice, with limited protocol-mandated procedures. | Maximize Ecological Validity. |

| Setting | Diverse, routine clinical care settings (e.g., community hospitals, primary care). | Enhance generalizability of findings. |

| Outcomes | Patient-centered outcomes that are clinically meaningful. | Ensure relevance to practice and policy. |

The Niche Applications of Observational Studies

Observational studies are not merely a fallback when RCTs are too expensive; they are the superior design for specific research niches defined by external validity requirements, feasibility constraints, and ethical imperatives [16] [9] [15].

- Enhancing External Validity and Generalizability: Observational studies include a broader range of patients, including those with comorbidities, polypharmacy, and diverse demographics who are often excluded from RCTs [20] [9]. This results in evidence that is directly applicable to "real-world" clinical populations and practice settings [17].

- Addressing Critical Feasibility Constraints: Observational designs are indispensable when RCTs are not practical. This includes studying rare diseases where patient recruitment for an RCT is impossible, long-term safety outcomes (e.g., assessing the risk of a rare adverse event years after drug approval), and rapidly evolving clinical fields where the slow pace of RCTs would render results obsolete by trial completion [12] [15].

- Providing Ethical Pathways for Evidence Generation: It is considered unethical to randomize patients when: a) an intervention is already the standard of care based on pathophysiological reasoning or longstanding use (e.g., the effect of intraoperative opioids); or b) there is a strong prior belief of harm or benefit that would make randomization unacceptable to clinicians or patients [16] [15]. In such scenarios, well-designed observational studies provide the only ethical source of comparative evidence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The following table details key "research reagents" and methodological solutions essential for conducting high-quality observational studies in the era of big data [19] [9].

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Methodological Solutions for Observational Research

| Tool / Solution | Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Records (EHRs) | Data Source | Provide comprehensive, real-world clinical data on patient history, treatments, and outcomes for large populations [19] [9]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Data Extraction | An AI technique to automate the extraction of unstructured clinical data (e.g., physician notes) into structured formats for analysis, dramatically improving feasibility [19]. |

| Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) | Causal Design | A graphical tool used to visually map out assumed causal relationships between variables, informing the selection of confounders to adjust for and minimizing bias [9]. |

| Propensity Score Methods | Statistical Analysis | A technique to simulate randomization by creating a balanced comparison group based on the probability of receiving the treatment given observed covariates, reducing selection bias [9]. |

| E-Value | Sensitivity Analysis | A metric that quantifies how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away an observed treatment-outcome association, assessing robustness to unmeasured confounding [9]. |

| Lomonitinib | Lomonitinib, CAS:2923221-56-9, MF:C27H24N4O2, MW:436.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TDI-10229 | TDI-10229, MF:C16H16ClN5, MW:313.78 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The body of evidence demonstrates that observational studies are not a inferior substitute for RCTs but a powerful methodology with a distinct and critical niche in the clinical research ecosystem. While RCTs remain the gold standard for establishing efficacy under ideal conditions, observational studies are paramount for understanding real-world effectiveness, addressing questions where RCTs are unfeasible or unethical, and providing timely evidence on long-term safety and rare outcomes. The advancement of sophisticated data sources like EHRs, and analytical methods like NLP and causal inference frameworks, has significantly enhanced the reliability and feasibility of observational research [19] [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic integration of both RCTs and observational studies—leveraging their complementary strengths—is the most robust path to generating the comprehensive evidence base needed to inform clinical practice and healthcare policy.

For decades, the randomized controlled trial (RCT) has been universally regarded as the gold standard for clinical evidence, occupying the apex of the evidence hierarchy due to its experimental design that minimizes bias through random allocation [21]. This historical primacy has been fundamental to pharmaceutical development and regulatory decision-making. Conversely, observational studies derived from real-world data (RWD) have often been viewed with skepticism, considered inferior for causal inference due to potential confounding and other biases [12].

However, the era of big data and advanced methodological innovations is catalyzing a paradigm shift. A more nuanced, complementary view is emerging, recognizing that both methodologies possess distinct strengths and limitations, and that the research question and context should ultimately drive the choice of method [9]. This guide objectively compares the performance of RCTs and observational studies within pharmaceutical comparative effectiveness research, providing the data and frameworks necessary for modern drug development professionals to navigate this evolving landscape.

Quantitative Comparison of Methodological Performance

Comparative Effectiveness and Safety Outcomes

A systematic landscape review assessed the comparability of relative treatment effects of pharmaceuticals from both observational studies and RCTs. The analysis of 74 paired pooled estimates from 30 systematic reviews across 7 therapeutic areas revealed a complex picture of concordance and divergence [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Relative Treatment Effects between RCTs and Observational Studies

| Metric of Comparison | Finding | Statistical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Statistical Difference | No statistically significant difference in 79.7% of pairs | Majority of comparisons showed agreement based on 95% confidence intervals [12] |

| Extreme Differences in Effect Size | Extreme difference (ratio <0.7 or >1.43) in 43.2% of pairs | Nearly half of comparisons showed clinically meaningful variation in effect magnitude [12] |

| Opposite Direction of Effect | Significant difference with estimates in opposite directions in 17.6% of pairs | A substantial minority of comparisons produced fundamentally conflicting results [12] |

Key Methodological Characteristics and Applications

The performance differences between RCTs and observational studies stem from their fundamental design characteristics, which make each suited to different research applications within drug development.

Table 2: Methodological Characteristics and Applications of RCTs vs. Observational Studies

| Characteristic | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Observational Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | High internal validity; controls for both known and unknown confounders via randomization [21] [9] | High external validity (generalizability); assesses effects under real-world conditions [9] |

| Primary Limitation | Limited generalizability due to selective populations and artificial settings [9] | Susceptibility to bias (e.g., confounding by indication) requiring sophisticated adjustment [22] |

| Ideal Application | Establishing efficacy under ideal conditions; regulatory approval [12] | Post-market safety surveillance; effectiveness in broader populations; rare diseases [12] [23] |

| Ethical Considerations | Required when clinical equipoise exists [21] | Preferred when RCTs are unethical (e.g., harmful exposures) [9] |

| Time & Cost | High cost, time-intensive, complex logistics [23] | Typically faster and more cost-efficient [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Standards

Core Protocol for a Traditional Randomized Controlled Trial

The following workflow outlines the standard methodology for a parallel-arm pharmaceutical RCT, highlighting steps designed to minimize bias.

Key Experimental Components:

- Random Allocation: Participants are randomly assigned to intervention or control groups, ensuring balance in both known and unknown baseline characteristics, which is the cornerstone of internal validity [21] [9].

- Blinding (Masking): Participants, investigators, and outcome assessors are often blinded to treatment assignment to prevent performance and detection bias.

- Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Analysis: Analyzes all participants in their originally assigned groups, regardless of adherence, to preserve the benefits of randomization [20].

- Protocolized Intervention: The treatment is delivered under standardized, controlled conditions to isolate its specific effect.

Core Protocol for a Modern Observational Study

Modern observational studies aiming for causal inference emulate the structure of an RCT using real-world data (RWD), such as electronic health records (EHRs) or claims databases.

Key Experimental Components:

- Target Trial Emulation: The study begins by explicitly defining the protocol for a hypothetical RCT that would answer the research question, then emulates it with observational data [9].

- Confounding Adjustment: This is a critical step to address bias by indication. Techniques include:

- Propensity Score Methods: The conditional probability of receiving the treatment given several measured confounding variables. Patients are matched or weighted based on their propensity score to create balanced comparison groups [23].

- Risk Adjustment: An actuarial tool that uses claims or clinical data to calculate a risk score for a patient based on their comorbidities, calibrating for the relative health of the compared populations [23].

- Sensitivity Analysis for Unmeasured Confounding: Techniques like the E-value are used to quantify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be to explain away the observed association, thus testing the robustness of the results [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Comparative Effectiveness Research

Table 3: Key Methodological Reagents for Modern Comparative Effectiveness Research

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score | Statistical Method | Balances measured covariates between exposed and unexposed groups in observational studies, mimicking randomization [23]. | Only adjusts for measured confounders; reliance on correct model specification. |

| E-Value | Sensitivity Metric | Quantifies the required strength of an unmeasured confounder to nullify an observed association, testing result robustness [9]. | Does not prove absence of confounding, but provides a quantitative measure of concern. |

| Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) | Causal Framework | Visual models that map assumed causal relationships between variables, guiding proper adjustment to minimize bias [9]. | Relies on expert knowledge and correct assumptions about the causal structure. |

| Cohort Intervention Random Sampling Study (CIRSS) | Novel Study Design | Combines strengths of RCTs and cohorts; participants from a prospective cohort are randomly selected for intervention offer [20]. | Aims to optimize implementation and generalizability while retaining some random element. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Emerging Technology | Assists in designing RCTs, potentially optimizing eligibility criteria and enhancing recruitment diversity and generalizability [24]. | Requires expert oversight; lower accuracy in designing outcomes and eligibility noted in early studies [24]. |

| Gcn2iB | Gcn2iB, MF:C18H12ClF2N5O3S, MW:451.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| STL127705 | STL127705, MF:C22H20FN5O4, MW:437.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The historical view of a rigid evidence hierarchy with RCTs at the apex is giving way to a more integrated and pragmatic framework. The body of evidence shows that while RCTs and observational studies can produce congruent findings, significant disagreement occurs in a meaningful proportion of comparisons [12]. The key for researchers and drug development professionals is to recognize that no single study design is equipped to answer all research questions [9].

The future of robust comparative effectiveness research lies in triangulation—the strategic use of multiple methodologies, with different and unrelated sources of bias, to converge on a consistent answer [9]. By understanding the specific performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and advanced tools available for both RCTs and observational studies, scientists can better design research programs and interpret evidence to ultimately improve pharmaceutical development and patient care.

Innovations in Trial Design and Real-World Evidence Generation

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard for evaluating pharmaceutical interventions. However, traditional explanatory RCTs, which test efficacy under ideal and controlled conditions, have limitations in generalizability, speed, and cost. This has spurred the development of advanced trial designs—adaptive, platform, and pragmatic trials—that aim to generate evidence more efficiently and applicable to routine clinical practice. This guide objectively compares these innovative designs against traditional RCTs and observational studies, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of comparative effectiveness research.

The fundamental goal of any clinical trial is to provide a reliable answer to a clinical question. Explanatory trials ask, "Can this intervention work under ideal conditions?" whereas pragmatic trials ask, "Does this intervention work under routine care conditions?" [25]. This distinction forms a continuum, not a binary choice, and is critical for understanding the place of advanced designs in the evidence ecosystem [26]. Simultaneously, the life cycle of clinical evidence is being reshaped by designs that can efficiently evaluate multiple interventions, such as platform trials, and those that can incorporate real-world data (RWD) to enhance generalizability and efficiency [27] [28]. These designs do not replace traditional RCTs but offer complementary tools whose selection depends on the specific research question, available resources, and the desired balance between internal validity and generalizability.

Comparative Analysis of Trial Designs

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of advanced RCT designs alongside traditional RCTs and observational studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced RCT Designs, Traditional RCTs, and Observational Studies

| Design Feature | Traditional (Explanatory) RCT | Observational Study | Pragmatic RCT (pRCT) | Platform Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | "Can it work?" (Efficacy) [25] | "How is it used?" (Association) | "Does it work?" (Effectiveness) [25] | "What is the best intervention?" (Comparative Efficacy) |

| Key Objective | Establish causal efficacy under ideal conditions [26] | Describe effectiveness/safety in routine practice [29] | Establish causal effectiveness in routine practice [26] | Efficiently compare multiple interventions against a common control [27] |

| Randomization | Yes, rigid | No | Yes, often flexible [28] | Yes, with potential for response-adaptation [27] |

| Patient Population | Highly selected, homogeneous [26] | Broad, heterogeneous, representative [29] | Broad, heterogeneous, representative [28] [26] | Can be broad, with potential for subgroup testing [27] |

| Setting & Intervention | Highly controlled, strict protocol | Routine clinical practice | Routine clinical practice, flexible delivery [28] | Can leverage a standing, shared infrastructure [27] |

| Comparator | Often placebo or strict standard of care | Various real-world comparators | Often usual care or active comparator [28] | A shared control arm (e.g., standard of care) [27] |

| Data Collection | Intensive, research-specific endpoints | Routinely collected data (e.g., EHR, claims) [29] | Streamlined, often using routine clinical data [28] | Varies, but often streamlined within the platform |

| Statistical Flexibility | Fixed, pre-specified analysis | Methods to control for confounding (e.g., propensity scores) [29] | Pre-specified, but may use intention-to-treat | Pre-specified adaptive rules (e.g., dropping futile arms) [27] |

| Relative Speed & Cost | Slow; High cost per question | Faster; Lower cost (but requires curation) [29] | Moderate to Fast; Moderate cost [28] | Slow initial setup; Lower cost per question over time [27] |

| Key Strength | High internal validity, minimizes bias | Large, diverse populations; long-term follow-up [29] | High external validity with retained randomization | Operational efficiency; rapid answer generation [27] |

| Key Limitation | Limited generalizability; may not reflect real-world use | Susceptible to confounding and bias [29] | Potential for lower adherence; larger sample sizes may be needed [26] | High initial cost and operational/complexity [27] |

Supporting Quantitative Data: A 2021 systematic review of 30 systematic reviews compared relative treatment effects of pharmaceuticals from RCTs and observational studies. It found that in 79.7% of 74 analyzed pairs, there was no statistically significant difference between the two designs. However, 43.2% of pairs showed an "extreme difference" (ratio of relative effect estimates <0.70 or >1.43), and in 17.6%, the estimates pointed in opposite directions [29]. This highlights that while many observational studies can produce results comparable to RCTs, a significant minority do not, underscoring the value of randomized designs like pRCTs for balancing internal and external validity.

Methodological Protocols and Experimental Workflows

Protocol for a Pragmatic Cluster-Randomized Trial

The Hyperlink hypertension trials provide a clear example of how design choices impact trial execution and outcomes [26].

- Workflow Objective: To compare the effects on blood pressure of a pharmacist-led telehealth intervention versus usual clinic-based primary care in a real-world setting.

- Trial Design: Cluster-randomized design, with primary care clinics as the unit of randomization to prevent contamination.

- Key Pragmatic Elements:

- Eligibility & Recruitment: Eligibility was based on criteria mirroring routine quality measures. In the pragmatic Hyperlink 3 trial, recruitment was integrated into the clinical workflow. An automated EHR algorithm identified eligible patients during primary care visits, and clinic staff (not researchers) managed enrollment [26].

- Intervention Delivery: The telehealth intervention was delivered by existing Medication Therapy Management (MTM) pharmacists within the healthcare system, not research staff.

- Follow-up & Data Collection: Patient follow-up and outcome data (blood pressure measurements) were primarily collected through routine clinical care and the EHR, minimizing extra research procedures.

- Outcome: The pragmatic Hyperlink 3 design successfully enrolled a much higher proportion of eligible patients (81% vs. 2.9% in the more explanatory Hyperlink 1) and better represented traditionally under-represented groups (more women, minorities, and patients with lower socioeconomic status). However, the trade-off was significantly lower adherence to the initial pharmacist visit (27% vs. 98% in Hyperlink 1), reflecting real-world challenges [26].

Protocol for a Bayesian Platform Trial

Platform trials represent a paradigm shift from standalone, fixed-duration trials to a continuous, adaptive learning system [27].

- Workflow Objective: To evaluate multiple interventions for a disease area under a single, ongoing master protocol, allowing interventions to be added or dropped as evidence accumulates.

- Core Protocol Features:

- Master Protocol: A single, overarching protocol governs the trial's operations, including a shared control arm, common infrastructure, and pre-specified rules for adaptation.

- Intervention Arms: Multiple intervention arms are tested simultaneously against a shared control (e.g., standard of care).

- Adaptive Rules: Pre-defined statistical rules guide the trial's evolution. These include:

- Futility Stopping: Dropping interventions that are highly unlikely to prove beneficial.

- Efficacy Stopping: Concluding that an intervention is superior to control and potentially making it the new control arm.

- Response-Adaptive Randomization: Adjusting randomization probabilities to favor interventions performing better.

- Adding New Arms: New interventions can be introduced into the platform as they become available, as long as they fit the master protocol.

- Operational Workflow: The entire process is supported by a shared infrastructure (clinical sites, data management, committees) and requires frequent, scheduled interim analyses to inform adaptations.

Successfully implementing advanced trial designs requires a suite of methodological, statistical, and operational tools.

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Advanced Trial Designs

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Trial Design & Planning | PRECIS-2 (Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary-2) [28] [26] | A 9-domain tool to help trialists design trials that match their stated purpose on the explanatory-pragmatic continuum. |

| Master Protocol Template [27] | A core protocol defining shared infrastructure, control arm, and adaptation rules for platform trials. | |

| Statistical Analysis | Bayesian Statistical Methods [27] | A flexible framework for sequential analysis, information borrowing across subgroups/arms, and probabilistic interpretation of efficacy in adaptive designs. |

| Computer Simulation [27] | Essential for determining statistical power and operating characteristics (type I error, etc.) of complex adaptive and platform trial designs. | |

| Data Sources & Management | Electronic Health Records (EHR) & Claims Data [28] | Real-world data sources used in pRCTs for patient identification, outcome assessment, and long-term follow-up to enhance efficiency. |

| Covidence / Rayyan [30] | Software tools that streamline the study screening and data extraction process for systematic reviews of existing literature during trial design. | |

| Operational Governance | Independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) | A standard committee for monitoring patient safety and efficacy data in all RCTs, critical for reviewing interim analyses in adaptive trials. |

| Statistical Advisory Committee [27] | A dedicated committee of statisticians to navigate the additional complexities of platform and adaptive trial designs. |

The landscape of clinical evidence generation is evolving. While traditional RCTs remain vital for establishing initial efficacy under controlled conditions, advanced designs offer powerful, complementary approaches. Pragmatic RCTs provide a robust method for assessing how an intervention performs in the messy reality of clinical practice, bridging the gap between RCT efficacy and real-world effectiveness. Platform trials offer unparalleled efficiency for answering multiple clinical questions in a dynamic, sustainable system, particularly in areas of persistent clinical equipoise. The choice of design is not a matter of which is universally "best," but which is most fit-for-purpose. By understanding the strengths, limitations, and specific methodologies of these advanced designs, researchers, and drug development professionals can better generate the evidence needed to inform medical practice and improve patient outcomes.

In the evidence-based world of pharmaceutical research, the comparative effectiveness of treatments has traditionally been established through Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). While RCTs remain the gold standard for establishing efficacy under controlled conditions, Real-World Data (RWD) is now indispensable for understanding how these treatments perform in routine clinical practice [31]. This guide provides a comparative overview of the three primary RWD sources—Electronic Health Records (EHRs), registries, and claims databases—to help researchers select the right tools for generating robust Real-World Evidence (RWE).

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each major RWD source, providing a foundation for selection and study design.

| Source Type | Primary Content & Purpose | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Records (EHRs) | Clinical data from patient encounters: diagnoses, medications, lab results, vital signs, progress notes [31]. | Rich clinical detail (e.g., disease severity, lab values); provides context for treatment decisions [31]. | Inconsistent data due to documentation for clinical care, not research; potential for missing data [31] [32]. |

| Claims Databases | Billing and administrative data for reimbursement: diagnoses (ICD codes), procedures (CPT codes), prescriptions [31]. | Large, population-level data; good for capturing healthcare utilization and costs; structured data [31]. | Limited clinical granularity (no lab results, disease severity); potential for coding inaccuracies [31]. |

| Registries | Prospective, structured data collection for a specific disease, condition, or exposure [31] [33]. | Data quality often higher due to collection for research; can capture patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [31] [33]. | Can be costly and time-consuming to maintain; potential for recruitment bias [33]. |

Methodological Frameworks for RWD Analysis

The observational nature of RWD introduces challenges, primarily confounding and selection bias, which require advanced methodologies to approximate causal inference [31] [34]. The following workflow outlines a structured approach to RWD analysis, from source selection to evidence generation.

Key Analytical Techniques

After defining the research question and preparing the data, selecting an appropriate analytical method is critical for robust evidence generation.

Propensity Score (PS) Methods: This approach balances covariates between treated and untreated groups to simulate randomization [31] [33]. A propensity score, the probability of a patient receiving the treatment given their observed characteristics, is estimated for each patient. Key techniques include:

- Propensity Score Matching (PSM): Pairs each treated patient with one or more untreated patients who have a similar propensity score, creating a matched cohort for comparison [31].

- Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW): Weights patients by the inverse of their propensity score, creating a synthetic population where treatment assignment is independent of measured confounders [34].

Causal Machine Learning (CML): Advanced ML models like boosting, tree-based models, and neural networks can handle high-dimensional data and complex, non-linear relationships better than traditional logistic regression for propensity score estimation [34].

- Doubly Robust Methods: Techniques like Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE) combine outcome regression and propensity score models. They provide a valid effect estimate even if one of the two models is misspecified, enhancing the robustness of findings [34].

G-Computation (Parametric G-Formula): This method involves building a model for the outcome based on treatment and covariates. It is then used to simulate potential outcomes for the entire population under both treatment and control conditions, estimating the average treatment effect by comparing these simulations [34].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for RWE

Successfully leveraging RWD requires a blend of data sources, methodological expertise, and technological tools. The table below details key components of the modern RWE researcher's toolkit.

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ONC-Certified EHR Systems (e.g., Epic, Oracle Cerner) [35] | Provides structured, standardized clinical data with interoperability via FHIR APIs for research. | Requires data curation for missingness and consistency; ensure API access for data extraction [36] [35]. |

| Advanced Statistical Software (R, Python with Causal ML libraries) | Enables implementation of PS methods, G-computation, and Doubly Robust estimators. | Causal inference requires explicit assumptions (e.g., no unmeasured confounding); model validation is critical [34]. |

| FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) Standards | Modern API-focused standard for formatting and exchanging healthcare data, crucial for aggregating data from multiple EHR systems [36] [35]. | Check vendor support for specific FHIR resources and versions [35]. |

| TEFCA (Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement) | A nationwide framework to simplify secure health information exchange between different networks, expanding potential data sources [36]. | Participation among networks is still evolving; understand data availability through Qualified HINs (QHINs) [36]. |

Propensity Score Software Packages (e.g., MatchIt in R) |

Facilitates the practical application of PSM, IPTW, and other propensity score techniques. | The choice of matching algorithm (e.g., nearest-neighbor, optimal) can influence results [31] [34]. |

| CCB02 | CCB02, MF:C14H9N3O, MW:235.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Parp-1-IN-32 | Parp-1-IN-32, MF:C21H16N2O5, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

RWE in Action: Case Studies and Regulatory Context

RWE is increasingly accepted by regulatory bodies like the FDA to support drug approvals and new indications, particularly when RCTs are impractical or unethical [32] [33].

- Expanding Treatment Options: The FDA approved a new "valve-in-valve" procedure for a transcatheter aortic valve replacement device by evaluating clinical and functional data from a registry of over 100,000 procedures. This RWE demonstrated the procedure's improvement without requiring a new RCT [32].

- Informing Chronic Disease Management: RWE studies have prompted critical re-evaluation of long-standing practices, such as the use of aspirin and beta-blockers for cardiovascular risk management, by revealing variations in effectiveness and safety profiles in real-world populations that were not apparent in initial RCTs [32].

The choice between RWD sources and analytical methods is not about finding a superior alternative to RCTs, but about selecting the right tool for the research question. The future of clinical evidence lies in a synergistic integration of RCTs and RWE [31] [37]. RCTs provide high internal validity for efficacy, while RWE from EHRs, claims, and registries offers critical insights into effectiveness, long-term safety, and treatment outcomes in heterogeneous patient populations seen in everyday practice. By systematically understanding the strengths and limitations of each RWD source and applying rigorous causal inference methodologies, researchers can robustly bridge the efficacy-effectiveness gap and advance patient-centered care.

The pursuit of causal knowledge represents a fundamental challenge in clinical research and drug development. For decades, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been regarded as the "gold standard" for establishing causal relationships between interventions and outcomes due to their ability to minimize bias through random assignment [1] [38]. However, RCTs face significant limitations including high costs, strict eligibility criteria that limit generalizability, ethical constraints for certain research questions, and protracted timelines that can render findings less relevant to current practice by publication time [9] [33]. These limitations have accelerated interest in robust methodological approaches for deriving causal inferences from observational data, creating a dynamic landscape where these approaches complement rather than compete with traditional RCTs.

The emergence of causal inference methods for observational data represents a paradigm shift in evidence generation, enabling researchers to approximate the conditions of randomized trials using real-world data (RWD) [9]. These methodological advances are particularly valuable in scenarios where RCTs are impractical, unethical, or insufficient for understanding how interventions perform in heterogeneous patient populations encountered in routine clinical practice [15] [33]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of causal inference methodologies for observational data against traditional RCTs, offering drug development professionals a framework for selecting appropriate approaches based on specific research contexts and constraints.

Foundational Concepts: Efficacy Versus Effectiveness

Understanding the distinction between efficacy and effectiveness is crucial for contextualizing the complementary roles of RCTs and observational studies. Efficacy refers to the extent to which an intervention produces a beneficial effect under ideal or controlled conditions, such as those in explanatory RCTs [1]. In contrast, effectiveness describes the extent to which an intervention achieves its intended effect in routine clinical practice [1]. This distinction explains why an intervention demonstrating high efficacy in RCTs may show reduced effectiveness in real-world settings where patient comorbidities, adherence issues, and healthcare system factors introduce complexity.

Pragmatic clinical trials (PrCTs) that use real-world data while retaining randomization have emerged as a hybrid approach that bridges the gap between explanatory RCTs and noninterventional observational studies [1]. These trials maintain the strength of initial randomized treatment assignment while evaluating interventions under conditions that more closely mirror actual clinical practice, thus providing evidence on both efficacy and effectiveness from the same study [1].

Table 1: Efficacy Versus Effectiveness in Clinical Research

| Dimension | Efficacy (RCTs) | Effectiveness (Observational Studies) |

|---|---|---|

| Study Conditions | Ideal, controlled conditions | Routine clinical practice settings |

| Patient Population | Highly selective based on strict inclusion/exclusion criteria | Broad, representative of real-world patients |

| Intervention Delivery | Standardized, tightly controlled | Variable, adapting to clinical realities |

| Primary Advantage | High internal validity | High external validity |

| Key Limitation | Limited generalizability | Potential for confounding bias |

Methodological Approaches: RCTs Versus Observational Studies

Randomized Controlled Trials: The Traditional Gold Standard

RCTs are prospective studies in which investigators randomly assign participants to different treatment groups to examine the effect of an intervention on relevant outcomes [9]. The fundamental strength of RCTs lies in the random assignment of the exposure of interest, which, in large samples, generally results in balance between both observed (measured) and unobserved (unmeasured) group characteristics [9]. This design ensures high internal validity and can provide an unbiased causal effect of the exposure on the outcome under ideal conditions [9].

The drug development process typically employs RCTs across multiple phases. Phase 1 trials primarily assess safety and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles with small numbers (20-80) of healthy volunteers [1]. Phase 2 trials evaluate safety and preliminary efficacy in approximately 100-300 patients with the target condition [1]. Phase 3 trials, considered pivotal for regulatory approval, are large-scale RCTs including approximately 1000-3000 patients conducted over prolonged periods to establish definitive safety and efficacy profiles [1]. Phase 4 trials occur after regulatory approval and collect additional information on safety, effectiveness, and optimal use in general patient populations [1].

Observational Studies: Leveraging Real-World Data

Observational studies include designs where investigators observe the effects of exposures on outcomes using existing data (e.g., electronic health records, administrative claims data) or prospectively collected data without intervening in treatment assignment [9] [39]. Major observational designs include:

- Case-control studies: Retrospective studies comparing groups with a disease or condition (cases) to those without (controls) to identify factors associated with the disease [39].

- Cohort studies: Longitudinal studies following groups of participants who share common characteristics, which can be prospective (following participants forward in time) or retrospective (using historical data) [39].

- Cross-sectional studies: Designs that assess both exposure and outcome at the same point in time [39].

The key disadvantage of observational studies is the lack of random assignment, opening the possibility of bias due to confounding and requiring researchers to employ more sophisticated methods to control for this important source of bias [9].

Causal Inference Methods for Observational Data

Causal inference methods refer to an intellectual discipline that allows researchers to draw causal conclusions from observational data by considering assumptions, study design, and estimation strategies [9]. These methods employ well-defined frameworks and assumptions that require researchers to be explicit in defining the design intervention, exposure, and confounders [9]. Key approaches include:

- Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs): Visual representations of causal assumptions that help identify potential confounders and sources of bias [9].

- Propensity Score Methods: Statistical approaches that create balance between treatment groups based on observed covariates, including matching, stratification, and inverse probability weighting [33].

- Instrumental Variable Analysis: Methods that use variables associated with treatment but not directly with outcome to account for unmeasured confounding [33].

- E-value Assessment: A metric that quantifies how strong unmeasured confounding would need to be to explain away an observed treatment-outcome association [9].

Table 2: Causal Inference Methods for Observational Data

| Method | Key Principle | Best Use Cases | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Matching | Balances observed covariates between treated and untreated groups | When comparing two treatments with substantial overlap in patient characteristics | No unmeasured confounding; overlap assumption |

| Instrumental Variables | Uses a variable associated with treatment but not outcome | When unmeasured confounding is suspected | Relevance, exclusion restriction, independence |

| Regression Discontinuity | Exploits arbitrary thresholds in treatment assignment | When treatment eligibility follows a clear cutoff | Continuity of potential outcomes at cutoff |

| Difference-in-Differences | Compares changes over time between treated and untreated groups | When pre- and post-intervention data are available | Parallel trends assumption |

| Synthetic Control Methods | Constructs weighted combinations of untreated units as counterfactual | When evaluating interventions in aggregate units (states, countries) | No interference between units |

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Dimensions

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

The comparative evaluation of RCTs and observational studies with causal inference methods requires consideration of multiple dimensions, including internal validity, external validity, implementation feasibility, and ethical considerations.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of RCTs and Observational Studies with Causal Inference Methods

| Dimension | Randomized Controlled Trials | Observational Studies with Causal Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Validity | High (due to randomization) | Variable (depends on method and assumptions) |

| External Validity | Often limited by strict eligibility | Generally higher (broader patient populations) |

| Time Requirements | Typically lengthy (years) | Shorter (can use existing data) |

| Cost Considerations | High (thousands to millions) | Lower (leverages existing data infrastructure) |

| Patient Population | Highly selective (narrow criteria) | Representative of real-world practice |

| Ethical Constraints | May be prohibitive for some questions | Enables study of questions unsuitable for RCTs |

| Confounding Control | Controls both measured and unmeasured | Controls only measured confounders |

| Generalizability | Limited to similar populations | Broader applicability to diverse patients |

| Implementation Complexity | High operational complexity | High analytical complexity |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Established as gold standard | Growing acceptance with robust methods |

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Recent research has provided empirical evidence comparing results from RCTs and observational studies employing causal inference methods. A study investigating the capability of large language models to assist in RCT design reported that while observational studies face methodological challenges, advances in causal inference methods are narrowing the gap between traditional RCT findings and real-world data [40]. Side-by-side comparisons suggest that analyses from high-quality observational databases often give similar conclusions to those from high-quality RCTs when proper causal inference methods are applied [15].

However, systematic reviews of observational studies frequently commit methodological errors by using unadjusted data in meta-analyses, which ignores bias by indication, immortal time bias, and other biases [41]. Of 63 systematic reviews published in top medical journals in 2024, 51 (80.9%) presented meta-analyses of crude, unadjusted results from observational studies, while only 22 (34.9%) addressed adjusted association estimates anywhere in the article or supplement [41]. This highlights the critical importance of applying appropriate causal inference methods rather than relying on naive comparisons when analyzing observational data.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol for Propensity Score Matching

Propensity score matching is one of the most widely used causal inference methods in observational studies of pharmaceutical effects. The standard protocol involves:

Define the Research Question: Clearly specify the target trial that would ideally be conducted, including inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment strategies, outcomes, and follow-up period.

Create the Study Cohort: Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria to the observational database to create the analytical cohort, ensuring adequate sample size for matching.

Estimate Propensity Scores: Fit a logistic regression model with treatment assignment as the outcome and all presumed confounders as predictors to calculate each patient's probability of receiving the treatment of interest.

Assess Overlap: Examine the distribution of propensity scores in treated and untreated groups to ensure sufficient overlap for matching.