Beyond the Average: A Strategic Framework for Handling Heterogeneity in Comparative Drug Efficacy Studies

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating clinical heterogeneity and Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects (HTE) in comparative effectiveness research.

Beyond the Average: A Strategic Framework for Handling Heterogeneity in Comparative Drug Efficacy Studies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating clinical heterogeneity and Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects (HTE) in comparative effectiveness research. Moving beyond the limitations of the Average Treatment Effect (ATE), we detail a strategic framework that spans from foundational concepts to advanced predictive modeling. The content explores the critical definitions of clinical and statistical heterogeneity, evaluates robust methodological approaches including the PATH Statement's risk and effect modeling, addresses common pitfalls in subgroup analysis, and outlines criteria for validating credible HTE. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging methodologies, this resource aims to empower scientists to generate more nuanced, clinically actionable evidence for personalized medicine and informed decision-making.

Understanding the Spectrum of Heterogeneity: From Clinical Diversity to Statistical Variation

Definition and Scope in Comparative Drug Efficacy Research

Clinical heterogeneity refers to the variability in the design and execution of studies included in systematic reviews (SRs) and comparative effectiveness research (CER). This variability is formally captured by the PICOTS framework, encompassing differences in Populations, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, Timeframes, and Settings [1]. In the context of comparative drug efficacy studies, such variability can significantly influence the observed intervention-disease association, potentially leading to biased conclusions or limiting the generalizability of findings if not properly accounted for [1].

International organizations, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Cochrane Collaboration, define clinical heterogeneity as the diversity in the populations studied, the interventions involved, and the outcomes measured [1]. It is crucial to distinguish this from statistical heterogeneity, which quantifies the degree of variation in effect sizes across studies and can arise from clinical or methodological heterogeneity, or from chance [1]. While statistical heterogeneity is a quantitative measure, clinical heterogeneity is a qualitative concept describing the underlying clinical or methodological reasons for that variation.

Framework for Assessment and Impact on Research Validity

Key Domains of Clinical Heterogeneity

The following table outlines the core domains of clinical heterogeneity and their implications for research validity.

Table 1: Domains of Clinical Heterogeneity and Their Impact on Research

| Domain | Description of Variability | Impact on Research Validity & Generalizability |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Populations | Demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), disease severity/stage, coexisting conditions (comorbidities), genetic profiles, risk factors [1]. | Influences whether an intervention-disease association holds across different patient subgroups. Effects may differ based on baseline risk or biological factors [1]. |

| Interventions & Comparators | Drug dosage/frequency, treatment duration, administration route, combination therapies (co-interventions), credibility of placebo, choice of active comparator (e.g., standard of care) [1]. | Impacts the ability to determine a drug's true efficacy and safety profile. Variability in control groups can make cross-trial comparisons difficult [2]. |

| Outcomes Measured | Definition of primary/secondary endpoints, method of outcome measurement (e.g., different survey instruments, laboratory techniques), timing of outcome assessment, follow-up duration [1]. | Hinders data synthesis if outcomes are not measured or reported consistently. Affects the assessment of long-term efficacy and safety [3]. |

Practical Example from Recent Research

A 2025 network meta-analysis (NMA) on first-line treatments for gastric/gastroesophageal junction cancer provides a clear example of managing clinical heterogeneity [2]. The analysis included trials of PD-1 inhibitors (tislelizumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab) combined with chemotherapy. To enable a valid indirect comparison, the researchers assumed the chemotherapy backbones were comparable and pooled them into a single node, acknowledging this as a potential source of clinical heterogeneity [2]. Furthermore, differences in how trials defined patient subgroups based on programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression levels represented variability in participant populations that needed careful consideration during analysis [2].

Methodologies for Evaluating and Managing Heterogeneity

Pre-Review Assessment Protocol

A structured feasibility assessment must be conducted before synthesizing data to evaluate clinical heterogeneity across trials [2]. This protocol involves comparing the following aspects of each included study:

- Study Design & Eligibility Criteria: Trial design (e.g., double-blind, open-label), key inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- Baseline Patient Characteristics: As summarized in Table 1 (demographics, disease status).

- Intervention/Comparator Details: As summarized in Table 1.

- Outcome Characteristics: Definitions, measurement methods, and follow-up times for outcomes like overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) [2].

This assessment determines whether studies are sufficiently similar to permit meaningful statistical synthesis or if the clinical heterogeneity is too great.

Analytical and Statistical Techniques

When synthesis is deemed appropriate, several techniques can be used to investigate and account for heterogeneity:

- Subgroup Analysis and Meta-Regression: These are hypothesis-driven techniques to examine if specific clinical factors (e.g., age, disease severity) are effect-measure modifiers—that is, if the treatment effect differs according to the level of that factor [1]. These factors should ideally be identified a priori during protocol development to avoid data dredging [1].

- Network Meta-Analysis (NMA): NMA allows for indirect comparisons of treatments across different trials. A key step is evaluating the transitivity assumption, which requires that the studies forming the "network" are sufficiently similar in their clinical and methodological characteristics (i.e., low clinical heterogeneity) to allow for valid indirect comparisons [2] [3].

- Restriction: This involves limiting the review to studies with narrowly defined participant populations or interventions. While this reduces heterogeneity, it also limits the applicability (generalizability) of the findings to a broader population [1].

Experimental and Research Reagent Solutions

Successfully navigating clinical heterogeneity requires a toolkit of methodological and statistical resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| PICOTS Framework | Provides a structured checklist to define the scope of a review and identify potential sources of clinical heterogeneity during study planning [1]. | Use protocol development to pre-specify key variables in populations, interventions, and outcomes. |

| GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) Approach | A systematic framework for rating the quality of evidence in a body of research, explicitly considering factors like inconsistency (heterogeneity) and indirectness [3]. | Apply to assess confidence in estimated treatment effects, especially when significant clinical heterogeneity is present. |

| Statistical Software (R, WinBUGS) | Platforms capable of performing complex meta-analyses, subgroup analyses, meta-regression, and network meta-analyses [2] [3]. | Essential for quantitative synthesis and modeling the impact of clinical heterogeneity on effect estimates. |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool | A critical appraisal tool to assess methodological heterogeneity and the potential for bias in included randomized controlled trials. | High methodological heterogeneity can compound clinical heterogeneity and threaten validity. |

| ACT / WCAG Contrast Guidelines | Rules for ensuring sufficient visual contrast in graphical outputs, which is critical for creating accessible and ethically sound data visualizations for scientific communication [4] [5]. | Apply when creating forest plots, network diagrams, and other figures to ensure accessibility for all readers. |

Mitigation Protocols and Best Practices for Study Design

A Priori Specification and Transparent Reporting

The most effective strategy for managing clinical heterogeneity is a priori specification. Factors that may be effect-measure modifiers should be identified during the protocol development stage of a systematic review or meta-analysis, before examining the results of the included studies [1]. This prevents "data dredging" and reduces the risk of spurious findings.

Furthermore, visualization of results should follow the principle of "showing the design" [6]. The first confirmatory plot for an experiment should be a "design plot" that breaks down the key dependent variable by all key manipulations, without omitting non-significant factors or adding interesting covariates post-hoc [6]. This practice is the visual analogue of pre-registration and promotes transparency.

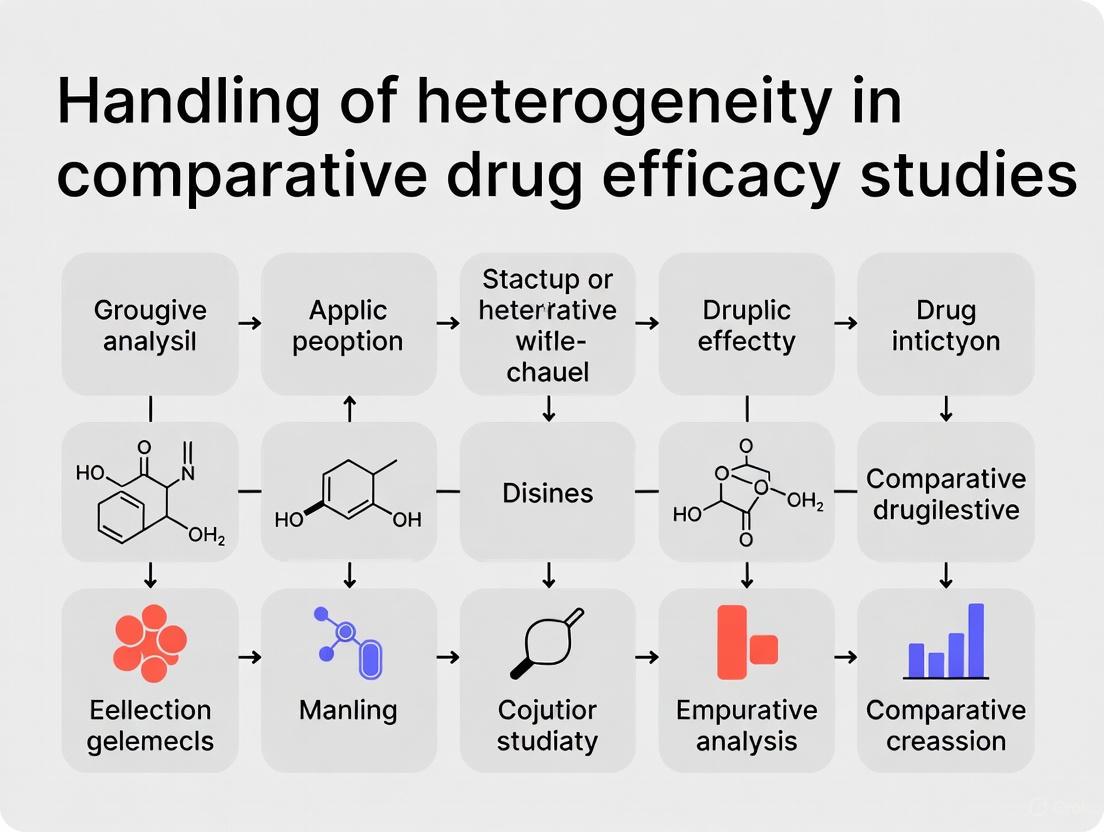

Integrated Workflow for Handling Heterogeneity

The following diagram synthesizes the core concepts and protocols into a unified workflow for defining, assessing, and managing clinical heterogeneity in comparative drug efficacy research.

In comparative drug efficacy studies, the accurate interpretation of treatment effects is fundamentally complicated by the presence of heterogeneity, which manifests in two distinct but interrelated forms: clinical and statistical heterogeneity. Clinical heterogeneity refers to differences in patient populations, intervention characteristics, or outcome measurements across studies or clinical settings [7]. This encompasses variability in factors such as patient demographics (age, sex), pathophysiology, disease severity, comorbid conditions, genetic profiles, and treatment modalities [8] [7]. In contrast, statistical heterogeneity represents the variability in treatment effects beyond what would be expected from chance alone, quantified through statistical measures [9] [10].

The causal relationship between these concepts is fundamental: clinical heterogeneity often serves as the underlying cause, while statistical heterogeneity represents its measurable effect. When clinical differences exist between patient subgroups or study populations, these differences manifest as statistical heterogeneity in the measured treatment effects [8]. This distinction is crucial for drug development professionals seeking to understand whether a treatment's variable performance represents meaningful clinical patterns or merely random statistical variation.

Failure to properly distinguish between these phenomena has significant implications for drug development and personalized medicine. Precision medicine initiatives depend on identifying clinically relevant heterogeneity to match specific treatments with patient subgroups most likely to benefit, while avoiding unnecessary treatment in those who will not respond or may experience harm [8] [11]. This paper provides application notes and experimental protocols to systematically distinguish clinical from statistical heterogeneity within comparative drug efficacy studies.

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Conceptual Foundations

Clinical heterogeneity arises from differences in patient biology, disease manifestations, treatment contexts, or environmental factors that modify treatment response. In pharmacoepidemiology, this is formally conceptualized as heterogeneity of treatment effects (HTE), defined as how the effects of medications vary across different people and treatment contexts [8]. Common clinical effect modifiers include age, sex, race, genotype, comorbid conditions, or other baseline risk factors for the outcome of interest [8].

Statistical heterogeneity represents the quantitative manifestation of these clinical differences when measured across studies or patient populations. It is mathematically defined as the variability in study effects beyond sampling error [9] [10]. The table below summarizes the key distinguishing characteristics:

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Clinical and Statistical Heterogeneity

| Characteristic | Clinical Heterogeneity | Statistical Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Conceptual/clinical diversity | Quantitative variability |

| Origin | Biological, clinical, or methodological diversity | Sampling error + clinical heterogeneity |

| Assessment | Clinical reasoning | Statistical tests |

| Primary concern | Clinical relevance | Statistical significance |

| Quantification | Descriptive measures | I², Q, H statistics |

| Addressability | Through subgroup definitions | Statistical modeling |

Scale Dependence of Heterogeneity

A critical consideration in heterogeneity analysis is scale dependence, where treatment effects may appear homogeneous on one measurement scale but heterogeneous on another [8]. For example, treatment effects may be constant on the risk difference scale but show significant heterogeneity on the risk ratio scale, or vice versa. This has profound implications for interpretation, as there is wide consensus that the risk difference scale is most informative for clinical decision-making because it directly estimates the number of people who would benefit or be harmed from treatment [8].

Quantitative Assessment of Statistical Heterogeneity

Core Statistical Measures

Statistical heterogeneity is quantified through several complementary measures, each with distinct interpretations and applications:

Cochran's Q statistic: A weighted sum of squared differences between individual study effects and the pooled effect across studies. Q follows a χ² distribution with k-1 degrees of freedom (where k is the number of studies). A significant Q statistic (p < 0.05 or 0.10) indicates heterogeneity beyond chance [9] [10].

I² statistic: Quantifies the percentage of total variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error, calculated as I² = 100% × (Q - df)/Q, where df represents degrees of freedom [9] [10]. Interpretation guidelines suggest:

- I² = 0%-25%: Low heterogeneity

- I² = 25%-50%: Moderate heterogeneity

- I² = 50%-75%: Substantial heterogeneity

- I² = 75%-100%: Considerable heterogeneity

H statistic: The square root of the ratio Q/df, with values greater than 1.5 suggesting notable heterogeneity [9].

Table 2: Statistical Measures for Heterogeneity Assessment

| Measure | Calculation | Interpretation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q statistic | Q = Σwᵢ(θᵢ - θ)² | p < 0.10 suggests significant heterogeneity | Direct test of heterogeneity | Low power with few studies; high power with many studies |

| I² statistic | I² = 100% × (Q - df)/Q | 0-25%: low; 25-50%: moderate; 50-75%: substantial; 75-100%: considerable | Independent of number of studies; comparable across meta-analyses | Confidence intervals often wide when number of studies small |

| H statistic | H = √(Q/df) | <1.2: negligible; 1.2-1.5: possible; >1.5: notable | Intuitive interpretation | Similar limitations to Q statistic |

| τ² (tau-squared) | Various estimators | Between-study variance | Absolute measure of heterogeneity | Sensitive to choice of estimator; difficult to interpret clinically |

Visualization Methods

Several graphical methods facilitate the assessment of statistical heterogeneity:

Forest plots: Display effect estimates and confidence intervals for individual studies alongside the pooled estimate, allowing visual assessment of consistency in effects and precision [10].

Galbraith plots: Plot standardized treatment effects (Z-statistics) against the precision of studies (1/standard error), where deviations from the regression line indicate potential outliers and heterogeneity [9].

L'Abbé plots: For binary outcomes, plot event rates in treatment groups against control groups, visually displaying heterogeneity in treatment effects across studies [9].

Methodological Approaches for Investigating Clinical Heterogeneity

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analysis examines whether treatment effects differ across predefined patient characteristics (e.g., age groups, disease severity, genetic markers) [8]. This method offers simplicity and transparency and can provide insights into drug mechanisms, but faces difficulties when multiple effect modifiers are present simultaneously [8].

Protocol 1: Subgroup Analysis Implementation

- Pre-specification: Identify potential effect modifiers and subgroup hypotheses before data analysis to minimize data-driven findings [8].

- Stratification variable selection: Choose variables based on biological plausibility, clinical relevance, and previous evidence [12].

- Analysis approach:

- Estimate treatment effects within each subgroup

- Test for interaction between treatment assignment and subgroup variable

- Use appropriate multiple testing corrections

- Interpretation: Focus on interaction tests rather than within-subgroup comparisons to avoid ecological fallacies.

Disease Risk Score (DRS) Methods

Disease Risk Score methods incorporate multiple patient characteristics into a summary score of baseline outcome risk, then examine treatment effect variation across risk strata [8]. This approach addresses limitations of single-variable subgroup analyses but may obscure mechanistic insights [8].

Effect Modeling Methods

Effect modeling approaches directly model individual treatment effects as a function of patient characteristics, offering potential for precise HTE characterization but requiring careful attention to model specification [8]. These include:

- Multivariable regression with treatment-covariate interaction terms

- Machine learning approaches (causal forests, Bayesian additive regression trees)

- Latent class models that identify subgroups with distinct treatment trajectories [11]

The eHTE Method for Direct HTE Estimation

A novel method termed 'estimated heterogeneity of treatment effect' (eHTE) directly tests the null hypothesis that a drug has equal benefit for all participants by comparing response distributions between treatment arms rather than testing specific covariates [11]. This approach:

- Sorts participants in each arm based on response, generating cumulative distribution functions

- Computes drug-placebo differences at each percentile

- Measures the standard deviation of these differences across percentiles as an approximation of HTE [11]

Protocol 2: eHTE Implementation

- Data requirements: Participant-level data from randomized controlled trials with continuous outcome measures [11].

- Analysis steps:

- Sort participants in each treatment arm by outcome value

- Generate cumulative distribution functions for each arm

- Compute treatment effect at each percentile

- Calculate standard deviation of these percentile-specific treatment effects

- Hypothesis testing: Compare observed eHTE to null distribution generated through permutation or simulation [11].

- Validation: Apply to simulated datasets with known heterogeneity patterns to calibrate interpretation [11].

Integrated Analytical Workflow

A comprehensive approach to distinguishing clinical from statistical heterogeneity requires sequential analytical phases:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Heterogeneity Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Methods | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (metafor, meta packages) | Comprehensive meta-analysis and heterogeneity quantification | General statistical analysis of aggregated data |

| Specialized Meta-analysis Tools | Stata (metan, metareg) | Flexible meta-analysis with subgroup and meta-regression capabilities | Complex modeling of heterogeneity sources |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Python (causalml, econml) | High-dimensional treatment effect modeling | Individualized treatment effect estimation |

| Data Visualization | R (ggplot2, forestplot) | Graphical assessment of heterogeneity | Forest plots, Galbraith plots, L'Abbé plots |

| Clinical Data Management | REDCap, Electronic Health Records | Structured data collection with clinical context | Real-world evidence generation for HTE |

| Genetic Analysis Tools | PLINK, SNPTEST | Pharmacogenetic effect modification analysis | Genotype-guided treatment effect heterogeneity |

Application to Real-World Data and Comparative Effectiveness Research

Real-world data (RWD) offers particular advantages for HTE assessment, including larger sample sizes, more diverse patient populations, and longer follow-up periods compared to randomized trials [8]. However, observational data introduces additional methodological challenges, particularly confounding, that require careful causal inference approaches.

Protocol 3: HTE Assessment in Real-World Data

- Data quality assessment: Evaluate completeness, accuracy, and relevance of RWD for addressing HTE questions [12].

- Confounding control: Implement propensity score methods, disease risk scores, or instrumental variables to address channeling bias and other confounding [8].

- HTE estimation: Apply subgroup analysis, effect modeling, or machine learning approaches to identify treatment effect modifiers [8].

- Validation: Use internal validation approaches (bootstrapping, cross-validation) and external validation when possible [12].

The growing availability of RWD creates unprecedented opportunities to understand treatment effect heterogeneity across diverse clinical contexts and patient populations, moving beyond the homogeneous treatment effects often assumed in randomized trials [8].

Distinguishing clinical from statistical heterogeneity requires a methodical, multi-stage approach that integrates quantitative assessment with clinical reasoning. Statistical heterogeneity serves as a signal that requires clinical interpretation, while clinical heterogeneity represents the substantive differences that may justify personalized treatment approaches. The proposed frameworks and protocols provide researchers and drug development professionals with structured methodologies to:

- Quantify and visualize statistical heterogeneity using appropriate measures

- Investigate potential clinical heterogeneity through subgroup analyses, effect modeling, and novel approaches like eHTE

- Interpret findings in the context of biological plausibility and clinical relevance

- Implement findings to advance personalized treatment strategies

Future directions in heterogeneity research include the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for high-dimensional treatment effect estimation, the development of standardized reporting guidelines for HTE assessments, and methodological advances for distinguishing true effect modification from various forms of bias in real-world settings.

Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects (HTE) refers to the non-random variability in the direction and magnitude of treatment effects across subgroups within a trial population [13]. In comparative drug efficacy studies, the average treatment effect often obscures significant variation in how individual patients or subpopulations respond to interventions. This variation stems from complex interactions between patient characteristics—including genetic, physiological, environmental, and clinical factors—and therapeutic mechanisms. Understanding HTE is fundamental to precision medicine, which aims to match the right treatment to the right patient by accounting for individual determinants of harm and benefit [13].

The identification and quantification of HTE face substantial methodological challenges, primarily arising from the fundamental problem of causal inference: researchers can only observe one potential outcome (the result under the administered treatment) for each patient, but never the simultaneous outcomes under both treatment and control conditions for the same individual [13]. This limitation necessitates sophisticated statistical approaches to estimate individualized treatment effects from group-level data. Furthermore, real-world data used to supplement randomized controlled trials often contain biases from unmeasured confounders, censoring, and outcome heterogeneity that must be carefully addressed [14].

Methodological Frameworks for HTE Analysis

Classification of Analytical Approaches

Regression-based methods for predictive HTE analysis can be classified into three broad categories based on how they incorporate prognostic variables and treatment effect modifiers [13].

Table 1: Methodological Approaches to HTE Analysis

| Approach Category | Key Components | Model Equation Features | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk-Based Methods | Prognostic factors only; relies on mathematical dependency of absolute risk difference on baseline risk | No covariate-by-treatment interaction terms | Individualized absolute benefit predictions based on baseline risk stratification |

| Treatment Effect Modeling | Both prognostic factors and treatment effect modifiers | Includes covariate-by-treatment interaction terms on relative scale | Subgroups with similar expected treatment benefits; individualized absolute benefit predictions |

| Optimal Treatment Regime | Primarily treatment effect modifiers | Focuses on covariate-by-treatment interactions for treatment assignment rules | Binary treatment assignment rules dividing population into those who benefit and those who do not |

Risk-based methods exploit the mathematical relationship between treatment benefit and a patient's baseline risk for the outcome, even when relative treatment effect remains constant across risk levels [13]. These approaches use only prognostic factors to define patient subgroups and do not include explicit treatment-covariate interaction terms. For example, Dorresteijn et al. combined existing prediction models with average treatment effects from RCTs to estimate individualized absolute treatment benefits by multiplying baseline risk predictions with the average risk reduction observed in trials [13].

Treatment effect modeling methods incorporate both the main effects of risk factors and covariate-by-treatment interaction terms (on a relative scale) to estimate individualized benefits [13]. These methods can be used either for making individualized absolute benefit predictions or for defining patient subgroups with similar expected treatment benefits. These approaches often employ data-driven subgroup identification coupled with statistical techniques to prevent overfitting, such as penalization or use of separate datasets for subgroup identification and effect estimation.

Optimal treatment regime methods focus primarily on treatment effect modifiers (covariate by treatment interactions) for defining a treatment assignment rule that divides the trial population into those who benefit from treatment and those who do not [13]. Contrary to other methods, baseline risk or the magnitude of absolute treatment benefit are not the primary concerns; instead, the focus is on identifying the optimal treatment choice for each patient.

Advanced Statistical Methods for HTE Estimation

Several advanced statistical approaches have been developed to address the challenges of HTE estimation, particularly when integrating multiple data sources or handling complex data structures.

For survival data with right censoring, the conditional restricted mean survival time (CRMST) difference provides an interpretable measure of HTE [14]. This approach defines HTE as the difference in the treatment-specific conditional restricted mean survival times given covariates. Recent methodologies have proposed using an omnibus bias function to characterize biases caused by unmeasured confounders, censoring, and outcome heterogeneity when integrating randomized clinical trial data with real-world data [14]. The proposed penalized sieve method estimates HTE and the bias function simultaneously, with studies demonstrating that this integrative approach outperforms methods relying solely on trial data.

In pre-post study designs, several statistical methods can be employed to estimate treatment effects while accounting for baseline characteristics [15]. These include:

- ANOVA-post: Compares post-test scores between groups while ignoring pre-test responses

- ANOVA-change: Analyzes change scores from pre-test to post-test

- ANCOVA-hom: Adjusts for baseline differences by incorporating pre-test score as a covariate with homogeneous slopes

- ANCOVA-het: Allows different relationships between pre-test and post-test scores for treatment and control groups (heterogeneous slopes)

- Linear Mixed Models (LMM): Handles repeated measurements within subjects using both fixed and random effects

The performance of these methods varies significantly depending on the randomization approach employed (simple randomization, stratified block randomization, or covariate adaptive randomization) and whether influential baseline covariates are adjusted for in the analysis [15].

Figure 1: HTE Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential process for conducting HTE analysis, from study design through clinical application.

HTE Detection in Network Meta-Analysis

Framework for Comparative Drug Efficacy

Network meta-analysis (NMA) provides a powerful framework for detecting HTE across multiple interventions when direct head-to-head comparisons are limited [16] [17] [18]. This approach allows for indirect comparisons of treatment effects while accounting for heterogeneity across studies. Recent advances in NMA methodology have enabled more sophisticated assessment of HTE by considering variations in study design, patient populations, and outcome measures.

A Bayesian framework is commonly employed for NMA, using Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation to quantify and demonstrate consistency between indirect comparisons and direct evidence [16]. The validity of NMA depends on the assumptions of transitivity and consistency, which require that clinical and methodological effect modifiers are similarly distributed across different pairwise comparisons, and that direct and indirect evidence agree [16]. Statistical methods like the node-splitting approach can evaluate consistency for each closed loop in the network.

Table 2: HTE Assessment in Recent Network Meta-Analyses

| Therapeutic Area | Interventions Compared | HTE Assessment Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild Cognitive Impairment [16] | 18 botanical drug interventions | Bayesian NMA with SUCRA rankings | Pycnogenol showed highest probability of improving cognitive function (SUCRA: 98.8%); treatment effects heterogeneous across cognitive domains |

| Ulcerative Colitis [17] | Biologics and small molecules | NMA stratified by trial design (re-randomized vs. treat-through) and prior therapy exposure | Upadacitinib 30mg ranked first for clinical remission in re-randomized studies (RR of failure: 0.52); efficacy heterogeneous based on trial design |

| Obese Knee Osteoarthritis [18] | Antidiabetic drugs | NMA with SUCRA rankings for efficacy and safety | Metformin most effective for pain (MD: -1.13); safety profiles heterogeneous across drug classes |

Accounting for Study Design Heterogeneity

The design of randomized controlled trials significantly influences HTE assessment in network meta-analyses. For ulcerative colitis treatments, efficacy rankings differed substantially between trials using re-randomization designs (where initial responders are re-randomized to active drug or placebo) and those using treat-through approaches (where treatment continues through follow-up without re-randomization) [17]. This highlights the importance of considering trial methodology when evaluating HTE, as different designs may estimate fundamentally different parameters.

Similarly, prior exposure to advanced therapies can substantially modify treatment effects. Network meta-analyses in ulcerative colitis have demonstrated different drug rankings for patients naive to advanced therapies compared to those with previous exposure [17]. This underscores the need for stratified analyses that account for treatment history when assessing HTE.

Experimental Protocols for HTE Detection

Protocol for HTE Analysis in Randomized Trials

Objective: To detect and quantify heterogeneity of treatment effects in a randomized controlled trial setting.

Materials and Methods:

- Study Population: Ambulatory adults (≥18 years) meeting trial eligibility criteria [17]

- Sample Size Considerations: Adequate power for subgroup analyses; often requires larger samples than average treatment effect estimation

- Randomization: Stratified block randomization or covariate adaptive randomization to balance key prognostic factors across treatment groups [15]

- Data Collection:

- Baseline covariates: Demographic, clinical, and biomarker data

- Treatment assignment: Randomized intervention

- Outcome measures: Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints, safety outcomes

- Statistical Analysis:

- Primary Analysis: Apply ANCOVA with heterogeneous slopes (ANCOVA-het) to allow different relationships between baseline and outcome for treatment and control groups [15]

- HTE Detection: Include treatment-by-covariate interaction terms to test for statistical interactions on an appropriate scale (relative or absolute)

- Subgroup Identification: Use treatment effect modeling methods with regularization to prevent overfitting [13]

- Validation: Internal validation through bootstrapping or cross-validation

Interpretation: Focus on clinically meaningful effect modification rather than statistical significance alone. Consider absolute risk differences in addition to relative effects.

Protocol for Integrating RCT and Real-World Data

Objective: To enhance HTE estimation by combining randomized clinical trial data with real-world data.

Materials and Methods:

- Data Sources:

- RCT data: Gold-standard but potentially limited in diversity and generalizability

- Real-world data: Registry data, electronic health records, claims data with potential biases [14]

- Data Structure:

- For subject i: (Xi, Ai, Ti, Ci, Δi, Si) where:

- X: p-dimensional covariate vector

- A: binary treatment (1=active, 0=control)

- T: failure time

- C: censoring time

- Δ: censoring indicator

- S: data source indicator (RCT or RWD) [14]

- For subject i: (Xi, Ai, Ti, Ci, Δi, Si) where:

- Integration Method:

- Define HTE Parameter: Conditional restricted mean survival time difference: Ï„(x) = E[Y(1) - Y(0) | X = x] where Y(a) is potential outcome under treatment a [14]

- Model Bias Function: Define omnibus bias function to characterize biases in real-world data from unmeasured confounders, censoring, and outcome heterogeneity

- Estimation: Use penalized sieve method to estimate HTE and bias function simultaneously

- Asymptotic Properties: Derive convergence rates and local asymptotic normalities using reproducing kernel Hilbert space and empirical process theory [14]

Interpretation: The integrative estimator should outperform RCT-only approaches in terms of efficiency and accuracy of HTE estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for HTE Research

| Tool / Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ANCOVA-het [15] | Estimates treatment effect while allowing different baseline-outcome relationships in treatment vs. control groups | Pre-post study designs with continuous outcomes |

| Penalized Sieve Method [14] | Estimates HTE and bias function simultaneously when integrating RCT and real-world data | Survival data with right censoring |

| SUCRA Rankings [16] [18] | Ranks interventions by probability of being best for each outcome | Network meta-analysis of multiple interventions |

| Node-Splitting Method [16] | Evaluates consistency between direct and indirect evidence in network meta-analysis | Validating transitivity assumption in NMA |

| AIPCW Transformation [14] | Handles right-censored survival outcomes while preserving conditional expectation | Time-to-event outcomes with censoring |

| Covariate Adaptive Randomization [15] | Balances multiple prognostic factors across treatment groups | RCTs with small sample sizes or many influential covariates |

| geldanamycin | geldanamycin, MF:C29H40N2O9, MW:560.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid-d3 | Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid-d3, MF:C9H6O6, MW:213.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Figure 2: HTE Method Classes and Their Characteristics: This diagram illustrates the three main methodological approaches to HTE analysis and their key features.

Understanding and accounting for heterogeneity of treatment effects is essential for advancing precision medicine and optimizing therapeutic decision-making. The methodologies reviewed—ranging from risk-based approaches to sophisticated integrative analyses combining RCT and real-world data—provide powerful tools for moving beyond average treatment effects to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from specific interventions. The consistent implementation of these methods in comparative drug efficacy studies will enable more personalized treatment recommendations and improve patient outcomes by ensuring that therapies are targeted to those who will derive the greatest benefit.

Future methodological development should focus on improving the robustness of HTE estimation in the presence of multiple data sources with different bias structures, enhancing validation approaches for individualized treatment effect predictions, and developing standardized reporting guidelines for HTE assessments in clinical studies. As these methods continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly critical role in drug development and evidence-based clinical practice.

The Critical Role of Effect Measure Modification

Effect Measure Modification (EMM) represents a fundamental concept in clinical epidemiology and comparative drug efficacy research, describing situations where the magnitude or direction of a treatment effect varies across levels of a third variable. Within the broader context of handling heterogeneity in comparative drug studies, EMM provides the methodological framework for understanding why medications work differently across diverse patient populations [8]. This phenomenon occurs when the causal effect of an exposure variable on an outcome depends on the level of a second variable [19]. Unlike confounding, which represents a nuisance to be eliminated, EMM often provides valuable insights for personalizing treatment strategies and understanding biological mechanisms [1] [8].

The distinction between EMM and statistical interaction is both subtle and critical. EMM exists when the effect of a primary exposure of interest varies across subgroups defined by another baseline characteristic [20]. In contrast, interaction concerns the joint effects of two exposures [19]. This distinction carries important implications for confounding adjustment: when studying EMM, only confounders of the primary exposure-outcome relationship require adjustment, whereas interaction analyses require control for confounders of both exposures [20].

Table 1: Key Terminology in Effect Measure Modification

| Term | Definition | Implications for Drug Efficacy Research |

|---|---|---|

| Effect Measure Modifier | A variable that influences the magnitude or direction of a treatment effect | Identifies patient characteristics associated with differential treatment response |

| Scale Dependence | Effect modification can be present on one scale (e.g., additive) but absent on another (e.g., multiplicative) [8] | Determines whether subgroup effects are reported as risk differences or risk ratios |

| Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects (HTE) | The broader phenomenon of treatment effects varying across patient subgroups [8] | Encompasses both explainable (via EMM) and unexplained variation in treatment response |

| Average Treatment Effect (ATE) | The overall effect of treatment averaged across all patients in a study [8] | May obscure important subgroup effects where benefits and harms cancel out |

Methodological Approaches for Investigating Effect Measure Modification

Conventional Analytical Frameworks

Traditional methods for investigating EMM rely on a priori specification of potential effect modifiers and stratified analyses. The subgroup analysis approach offers simplicity and transparency, providing easily interpretable estimates of treatment effects within predefined patient subgroups [8]. However, this method faces limitations when multiple potential effect modifiers coexist, as it cannot simultaneously account for numerous patient characteristics [8].

Disease risk score (DRS) methods incorporate multiple patient characteristics into a summary score of baseline outcome risk, addressing some limitations of simple subgroup analyses [8]. While clinically useful for identifying high-risk patients who might derive greater absolute benefit from treatment, DRS approaches may obscure insights into biological mechanisms because they create composite scores that blend multiple patient attributes [8].

Effect modeling methods directly model how treatment effects vary with patient characteristics, offering more precise characterization of heterogeneity [8]. These approaches include regression models with interaction terms between treatment and potential effect modifiers, but they require careful specification to avoid model misspecification [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Methodological Approaches for EMM Analysis

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup Analysis | Stratified analysis by predefined patient characteristics | Simple, transparent, provides mechanistic insights [8] | Does not account for multiple characteristics simultaneously; risk of spurious findings |

| Disease Risk Score (DRS) | Creates composite score of baseline outcome risk | Clinically useful for absolute risk assessment; relatively simple implementation [8] | May obscure mechanistic insights; requires validation |

| Effect Modeling | Directly models treatment effect heterogeneity | Potential for precise HTE characterization; can handle multiple modifiers [8] | Prone to model misspecification; complex interpretation |

Modern Machine Learning Approaches

Recent methodological advances have introduced machine learning (ML) techniques for EMM analysis, particularly valuable in high-dimensional settings with numerous potential effect modifiers [21]. Generalized Random Forests extend standard random forests to provide non-parametric estimation of heterogeneous treatment effects, capable of detecting complex interaction patterns without pre-specification [21]. Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART) offer a flexible approach for estimating treatment effect heterogeneity while naturally incorporating uncertainty quantification [21]. Metalearner frameworks, including S-, T-, X-, and U-learners, provide flexible estimation strategies that can be combined with various base ML algorithms [21].

These data-driven approaches serve an important role in discovering vulnerable subgroups when prior knowledge is limited, though they cannot replace domain expertise in identifying plausible effect modifiers [21]. ML methods are particularly valuable for generating hypotheses about potential treatment effect modifiers in exploratory analyses, which should then be validated in independent datasets or through mechanistic studies.

Protocols for Detecting and Reporting Effect Measure Modification

Protocol 1: Stratified Analysis for Effect Measure Modification

Objective: To assess whether a baseline characteristic modifies the effect of an intervention on a dichotomous outcome.

Preparatory Steps:

- A Priori Specification: Identify potential effect modifiers during protocol development based on biological plausibility or prior evidence [1].

- Data Collection: Ensure complete ascertainment of potential effect modifiers and confounding variables at baseline.

- Confounder Adjustment: Identify and adjust for confounders of the relationship between the primary exposure and outcome [20].

Analytical Procedure:

- Stratified Analysis: Calculate stratum-specific effect estimates (e.g., risk ratios, risk differences) for each level of the potential effect modifier [20].

- Reference Category Selection: Use a single reference category for all comparisons, preferably the stratum with the lowest outcome risk [20].

- Effect Measure Calculation: Compute both ratio and difference measures for each stratum [20].

- Formal Testing: Assess effect modification on both additive and multiplicative scales with calculation of confidence intervals [20].

Reporting Standards:

- Present relative risks, odds ratios, or risk differences with confidence intervals for each stratum of exposure and effect modifier [20].

- Report measures of effect modification on both additive and multiplicative scales with confidence intervals and p-values [20].

- List all confounders for which the relationship between exposure and outcome was adjusted [20].

Protocol 2: Analysis of Effect Modification Using Real-World Data

Objective: To characterize heterogeneity of treatment effects using real-world data (RWD) to enhance generalizability and precision.

Preparatory Steps:

- Data Quality Assessment: Evaluate completeness, accuracy, and relevance of RWD sources for addressing the research question [8].

- Confounding Control: Implement appropriate methods (e.g., propensity scores, disease risk scores) to address confounding in non-randomized data [8].

- Sensitivity Analyses: Plan analyses to assess robustness of findings to potential unmeasured confounding.

Analytical Procedure:

- ATE Estimation: Calculate the average treatment effect using appropriate methods for observational data.

- HTE Assessment: Apply ML methods or stratified analyses to identify systematic variation in treatment effects [8].

- Scale Assessment: Evaluate effect modification on both additive (risk difference) and multiplicative (risk ratio) scales [8].

- Precision Evaluation: Assess statistical precision of subgroup-specific effect estimates.

Reporting Standards:

- Clearly describe the source and characteristics of the RWD used [8].

- Report the frequency of outcomes in each level of the effect modifier with and without treatment [8].

- Present absolute risks in addition to relative measures to facilitate clinical interpretation [8].

- Acknowledge limitations of RWD, including potential residual confounding [8].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EMM Analysis

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Implementation of ML methods for HTE (generalized random forests, BART) [21] | High-dimensional effect modification analysis |

| SAS/PROC GENMOD | Regression with interaction terms for subgroup analysis | Conventional stratified analysis of EMM |

| Python/Scikit-learn | Metalearner implementation for heterogeneous treatment effects | Flexible estimation of treatment effect modification |

| RevMan | Cochrane's tool for meta-analysis of subgroup effects [22] | Systematic review of EMM across multiple studies |

Visualization and Interpretation of Effect Measure Modification

Graphical Representation of Effect Modification

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting and communicating complex EMM findings. The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships in EMM analysis:

Scale Dependence in Effect Measure Modification

The phenomenon of scale dependence represents a critical consideration in EMM analysis, wherein effect modification may be present on one scale of measurement but absent on another [8]. This occurs because ratio measures (e.g., risk ratios) and difference measures (e.g., risk differences) reflect different mathematical properties of effect variation [8].

Table 4: Scale Dependence in Effect Measure Modification

| Scenario | Risk Difference Scale | Risk Ratio Scale | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant additive effect | No effect modification | Effect modification present | Absolute benefit consistent, relative benefit varies |

| Constant multiplicative effect | Effect modification present | No effect modification | Relative benefit consistent, absolute benefit varies |

| Dual-scale effect modification | Effect modification present | Effect modification present | Both relative and absolute benefits vary substantially |

For clinical decision-making, there is wide consensus that the risk difference scale is most informative because it directly estimates the number of people who would benefit or be harmed from treatment [8]. However, ratio measures remain commonly reported in the literature due to statistical convenience and conventional practices [8].

Implementation in Drug Development and Comparative Effectiveness Research

Practical Applications in Pharmacoepidemiology

In pharmacoepidemiology, EMM analysis addresses fundamental questions about why medications work differently across individuals and populations [8]. This understanding enables tailoring of treatment strategies to maximize benefit-risk profiles for individual patients [8]. For example, identifying that patients with specific genetic polymorphisms experience higher rates of adverse drug reactions allows for targeted prescribing and monitoring [8].

The integration of RWD has expanded opportunities for EMM investigation by providing larger sample sizes and more diverse patient populations than typically available in randomized trials [8]. This enhanced statistical power allows for more precise estimation of subgroup-specific treatment effects and detection of rare adverse outcomes that may be modified by patient characteristics [8].

Methodological Considerations for Valid Inference

Robust EMM analysis requires careful attention to methodological principles to ensure valid inferences. A priori specification of potential effect modifiers should be preferred over post hoc data dredging to minimize spurious findings [1]. The distinction between EMM and interaction must be maintained, as the analytical approach and confounding control requirements differ substantially [20] [19].

When using ML methods for EMM analysis, researchers should prioritize interpretability and clinical relevance over pure predictive performance [21]. Complex ML models may identify novel subgroups with differential treatment response, but these findings require validation in independent datasets and assessment of biological plausibility before influencing clinical practice [21].

The evolving methodology for EMM analysis continues to enhance our ability to understand and predict heterogeneity in drug effects, ultimately supporting more personalized and effective pharmacotherapy across diverse patient populations.

Why the 'Average Treatment Effect' is Often Misleading for Clinical Decision-Making

The 'Average Treatment Effect' (ATE), derived from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), serves as a cornerstone of evidence-based medicine. It provides an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect on average across a study population [23]. However, a fundamental incongruity exists: while evidence is generated from groups, medical decisions are made for individuals [23]. The ATE offers a single summary statistic, implicitly assuming that patients with the same disease are identical in all factors that influence their potential to benefit or be harmed by a therapy. In reality, patients differ markedly in characteristics such as age, genetic makeup, disease severity, comorbidities, and environmental exposures [23] [24]. These differences can lead to substantial variation in how individuals respond to treatment, a phenomenon known as Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects (HTE).

Relying solely on the ATE can therefore be misleading for clinical decision-making. It can result in administering powerful treatments to some patients who will derive little benefit while exposing them to potential harms, or conversely, in withholding treatment from others who might benefit substantially [25]. This paper explores the limitations of the ATE, critiques conventional methods for investigating HTE, and presents advanced predictive approaches that move toward a more patient-centered evidence base, framed within the context of comparative drug efficacy research.

The Critical Limitations of the Average Treatment Effect

The Fallacy of the "Average Patient"

The concept of an "average patient" is a statistical abstraction that may not correspond to any real-world individual. The following table summarizes the key reasons why the ATE is an insufficient guide for individual-level decisions.

Table 1: Why the Average Treatment Effect is Misleading for Clinical Decisions

| Limitation | Underlying Cause | Consequence for Decision-Making |

|---|---|---|

| Masking of Heterogeneity | The ATE summarizes a population's response, which may be composed of a spectrum of large positive, negligible, and large negative effects for individuals [23]. | Clinicians cannot discern if their specific patient is likely to be a responder, a non-responder, or one who experiences harm. |

| Oversimplification of Outcomes | Medical decisions involve weighing multiple outcomes simultaneously (e.g., efficacy, safety, cost, quality of life) [25]. The ATE typically focuses on a single primary efficacy outcome. | A favorable ATE on a primary efficacy outcome may obscure significant detriments on other outcomes that are crucial to a patient's decision. |

| Susceptibility to Population Shifts | The ATE is specific to the distribution of effect-modifying characteristics in the trial population [25]. | An ATE from a highly selected trial population may not be generalizable to a different patient in routine practice with a distinct clinical profile. |

| Indifference to Baseline Risk | The absolute treatment benefit is mathematically dependent on a patient's baseline risk of the outcome event [23]. | Patients at low baseline risk will derive small absolute benefit even if the relative risk reduction (a common ATE) is constant across risk groups. Treating them may not be worthwhile. |

The Problem of "Sorting on the Mix"

A particularly complex challenge arises when treatment choice in the real world is based on a "mix" of expected benefits and detriments. Simulation studies show that when treatment effects are heterogeneous across multiple outcomes (e.g., survival benefit vs. risk of a severe adverse event), and treatment choices reflect this, the interpretation of treatment effect estimates becomes highly sensitive to the study population [25].

For example, a patient subgroup with a high expected survival benefit might also have a high risk of severe adverse effects. In practice, these patients might be less likely to receive the treatment (a "treatment-risk paradox") because the perceived detriment outweighs the benefit [25]. Analyses focusing only on the survival ATE would misinterpret this rational clinical decision as under-treatment, failing to capture the nuanced trade-off being made across multiple outcome dimensions.

From Simple Subgroups to Predictive Approaches

The Inadequacy of One-Variable-at-a-Time Subgroup Analysis

The conventional approach to exploring HTE is subgroup analysis, where the treatment effect is estimated separately for categories of a single variable (e.g., age, sex). This method has severe limitations:

- Low Statistical Power: Each subgroup is smaller than the full population, increasing the risk of false-negative findings.

- Inability to Account for Confounding: Subgroups defined by one variable (e.g., elderly) are often confounded by others (e.g., higher comorbidity burden), making it difficult to isolate the true effect modifier [23].

- High Risk of False Positives: Testing multiple subgroups without adjustment increases the likelihood of finding a spurious significant difference by chance alone.

Predictive Approaches to Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

Modern analytical approaches move beyond univariate subgroup analysis to develop multivariate models that predict an individual's specific treatment effect.

Table 2: Predictive Approaches for Modeling Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

| Approach | Methodology | Key Advantage | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Modeling | Develops a model to predict an individual's baseline risk of the outcome event without treatment. The absolute treatment benefit is a function of this baseline risk [23]. | Leverages the mathematical fact that absolute benefit is often correlated with baseline risk. Can be practice-changing and is relatively straightforward to implement. | Does not directly model how specific patient variables modify the relative treatment effect. Assumes a constant relative treatment effect across risk strata. |

| Effect Modeling | Develops a model directly on clinical trial data that includes not only prognostic variables but also interaction terms between patient variables and the treatment assignment [23]. | Directly estimates how multiple variables simultaneously modify the treatment effect, potentially providing more granular, individualized effect estimates. | Prone to statistical overfitting, especially when the number of potential effect modifiers is high and the trial sample size is limited. Requires strong prior knowledge. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the process of developing and applying these predictive models in clinical research.

Predictive HTE Analysis Workflow

Experimental Protocols for HTE Analysis

Protocol 1: Risk-Based HTE Analysis

This protocol uses baseline risk to explore heterogeneity in the absolute treatment effect.

- Objective: To assess how the absolute benefit of a treatment varies across subgroups defined by their baseline risk of the primary outcome.

- Data Source: Individual participant data from a single large RCT or, preferably, from an individual patient data meta-analysis of multiple trials to ensure adequate power.

- Prognostic Model Development:

- Using the control group data only, develop a multivariable model (e.g., Cox regression, logistic regression) to predict the probability of the primary outcome based on relevant prognostic baseline characteristics.

- Validate the model's performance (discrimination, calibration) using internal (e.g., bootstrapping) or external validation techniques.

- Risk Stratification:

- Apply the developed prognostic model to all participants in the trial (both treatment and control groups) to assign a predicted baseline risk score.

- Categorize participants into quartiles or quintiles of baseline risk.

- Treatment Effect Estimation:

- Within each risk stratum, calculate the absolute risk reduction (ARR) and its confidence interval. The number needed to treat (NNT) can be derived as 1/ARR.

- Visually present the results using a plot showing ARR (and NNT) across the continuum of baseline risk.

Protocol 2: Effect Modeling Using the Target Trial Approach with Real-World Data

When RCTs are not available, this protocol outlines a robust framework for estimating heterogeneous effects from real-world data (RWD) by emulating a hypothetical RCT [26].

- Objective: To emulate a target trial and estimate the effect of a new drug versus standard of care, and its potential heterogeneity, using observational data.

- Target Trial Protocol:

- Explicitly define the key components of the target trial: Patient eligibility criteria, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, Time zero (start of follow-up), and Study follow-up period.

- Data Curation:

- Select a suitable real-world data source (e.g., electronic health records, claims database) that can adequately capture the PICOTS.

- Carefully curate the data to ensure the operational definitions of variables (exposure, outcome, confounders) are consistent with the target trial.

- Statistical Analysis to Control for Confounding:

- Identify a comprehensive set of potential confounders using causal diagrams (e.g., DAGs).

- Use advanced statistical methods to address confounding. The choice depends on the data and available instruments:

- Propensity Score Methods: (e.g., matching, weighting) to create a balanced comparison group.

- Instrumental Variable (IV) Analysis: If a suitable instrument is available (e.g., regional variation in prescribing preference) and assumptions are met, this can address unmeasured confounding [26].

- HTE Analysis:

- After accounting for confounding, incorporate pre-specified interaction terms between the treatment and key patient characteristics (e.g., age, biomarker status) into the outcome model.

- Use machine learning methods like causal forests, which are designed to handle high-dimensional data and discover heterogeneous effects without pre-specification, while being robust to overfitting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HTE Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects Studies

| Item / Solution | Function & Application in HTE Research |

|---|---|

| Individual Participant Data (IPD) | The foundational raw material. IPD from clinical trials or high-quality observational studies is essential for developing and validating predictive models of treatment effect [23]. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | The primary laboratory. Environments like R (with packages for survival analysis, grf for causal forests) and Python (with libraries like EconML, scikit-learn) are used to implement risk and effect modeling techniques. |

| Causal Inference Frameworks | The theoretical blueprint. Frameworks such as Target Trial Emulation and Causal Diagrams (DAGs) provide the structure for designing valid analyses, particularly when using real-world data to investigate HTE [26]. |

| Data Visualization Tools | The communication lens. Tools like ChartExpo or advanced plotting libraries in R/Python are critical for creating clear visualizations of heterogeneous effects, such as plots of treatment effect across the spectrum of baseline risk or forest plots of subgroup effects [27] [28]. |

| Edaravone D5 | Edaravone D5 Stable Isotope |

| (R)-Cinacalcet-D3 | (R)-Cinacalcet-D3|CAS 1228567-12-1|High Purity |

The average treatment effect is a useful starting point but a dangerous endpoint for evidence-based medicine. Its uncritical application obscures the fundamental reality that treatment effects are heterogeneous across individual patients and across multiple outcomes. To advance comparative drug efficacy research, the field must move beyond the ATE and conventional, underpowered subgroup analyses. By adopting predictive approaches like risk and effect modeling, and by rigorously applying frameworks like the target trial approach to real-world data, researchers can generate the nuanced, personalized evidence needed to inform truly patient-centered therapeutic decisions. The future of evidence-based medicine lies not in knowing what works on average, but in predicting for whom it works best.

Advanced Analytical Approaches: From Subgroup Analysis to Predictive Modeling of HTE

Subgroup analyses are a fundamental step in assessing evidence from confirmatory (Phase III) clinical trials, investigating whether treatment effects are homogeneous across the study population [29]. Eligibility criteria for large trials are often broad to ensure the trial results can be generalized to a larger patient population, making subgroup analysis essential for interpreting whether conclusions for the overall study population hold for all patient subsets [30]. These analyses evaluate whether the treatment effect of a new drug varies across subgroups defined by demographic variables (e.g., age, sex, race) or variables prognostic of clinical outcomes (e.g., disease severity, biomarker status) [30].

In comparative drug efficacy studies, subgroup analyses serve distinct purposes: investigating consistency of treatment effects across clinically important subgroups, exploring treatment effects within an overall non-significant trial, evaluating safety profiles limited to specific subgroups, or establishing efficacy in a targeted subgroup included in a confirmatory testing strategy [29]. The growing biological and pharmacological knowledge driving personalized medicine makes these analyses particularly relevant for identifying subgroups with differential benefit-risk profiles [29].

Defining Subgroups and Understanding Treatment Effect Heterogeneity

Subgroup Definition Methodologies

Subgroups can be defined using various approaches, each with specific methodological considerations. Demographic subgroups (age, sex, race) are commonly examined, while subgroups defined by prognostic variables (disease severity, prior therapies) or predictive biomarkers (genotype, biomarker status) are increasingly important in targeted therapy development [30].

For continuous variables, using well-established or published cutoffs is preferred. In oncology, for example, age cutoffs of 40 and 65 years commonly classify patients into adolescent/young adult (<40), adult (40-65), and older adult (>65) subgroups [30]. When common cutoffs are unavailable, data-driven approaches such as percentiles (e.g., median) or statistical graphs may be used, though these require caution regarding plausibility and reproducibility [30].

When multiple variables contribute to subgroup definition, a continuous prediction score from a multivariable prediction model can categorize patients into risk groups (low, moderate, high). Optimal cutoff points for novel biomarkers or risk scores are often chosen to maximize outcome differences or treatment benefits between subgroups [30].

Heterogeneity of Treatment Effect

The statistical term for differential treatment effects across subgroups is treatment-by-subgroup interaction [30]. This interaction can be quantitative or qualitative:

- Quantitative interactions: Treatment effect size varies across subgroups but remains in the same direction

- Qualitative interactions: Treatment effect direction differs across subgroups (beneficial in one subgroup, harmful in another)

Table 1: Types of Treatment-Subgroup Interactions

| Interaction Type | Description | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| No Interaction | Consistent treatment effect across subgroups | Same therapeutic implication for all subgroups |

| Quantitative Interaction | Varying magnitude of effect, same direction | Same therapeutic implication but potentially different benefit magnitude |

| Qualitative Interaction | Opposite effect directions between subgroups | Critical therapeutic consequences; treatment may benefit one subgroup while harming another |

A classic example of qualitative interaction comes from the IPASS trial in non-small cell lung cancer, where gefitinib showed significantly better progression-free survival versus control in EGFR mutants but significantly worse progression-free survival in EGFR wild-type patients [30]. This makes EGFR mutation status a predictive biomarker for gefitinib response.

Statistical Power and Multiple Testing Considerations

Power Limitations in Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses in randomized controlled trials designed primarily to evaluate overall treatment effects are frequently under-powered [30]. The test for treatment-by-subgroup interaction has roughly four times the variance of an overall treatment effect test when subgroup sizes are equal, necessitating substantially larger sample sizes that are seldom feasible [30]. Consequently, failure to detect a statistically significant interaction does not necessarily indicate absence of treatment effect heterogeneity.

Low power in subgroup analyses is particularly problematic when exploring multiple subgroups or when interaction effects are modest. Equal allocation of patients across subgroups yields the highest power, but this is often not reflected in trial designs [30]. For biomarker-stratified trials, specific strategies can optimize power for detecting treatment-by-subgroup interactions [30].

Type I Error Inflation and Multiple Testing Controls

Conducting multiple statistical tests across numerous subgroups substantially inflates the false positive rate [30]. With 10 independent tests conducted at a 5% significance level, the chance of at least one false positive finding is approximately 40% when no true treatment effects exist [30].

Table 2: Multiple Testing Correction Methods

| Method | Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonferroni Correction | Divides significance level by number of tests | Simple implementation, controls family-wise error rate | Overly conservative, ignores correlation between tests |

| Sequential Testing (Gating) | Tests overall effect before subgroup effects | Preserves power for primary analysis | May miss targeted subgroup effects when overall effect nonsignificant |

| Fallback Procedure | Allows recycling of significance level after rejecting hypotheses | More powerful than Bonferroni, incorporates testing order | More complex implementation |

| MaST Procedure | Accounts for correlation between subgroup and overall tests | Improved power compared to Bonferroni | Requires specialized statistical expertise |

More flexible multiple testing procedures like the fallback and MaST procedures account for correlation between outcomes and allow recycling significance levels after rejecting hypotheses, offering improved power over traditional Bonferroni correction [30].

A Priori Specification and Analysis Protocols

Confirmatory vs. Exploratory Subgroup Analyses

Confirmatory subgroup analyses intended to support subgroup-specific efficacy claims must be pre-specified in the trial design with clearly defined subgroups and endpoints [30]. These require strict control of type I error and appropriate sample size planning. In contrast, exploratory subgroup analyses may generate hypotheses for future research but should not form definitive conclusions about differential treatment effects [29].

The purpose of subgroup analyses should guide their design and interpretation. Four distinct purposes include: (1) investigating consistency of treatment effects across clinically important subgroups, (2) exploring treatment effects across subgroups within an overall non-significant trial, (3) evaluating safety profiles limited to specific subgroups, and (4) establishing efficacy in a targeted subgroup within a confirmatory testing strategy [29].

Statistical Analysis Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing for Treatment-by-Subgroup Interaction

- Pre-specification: Define subgroups of interest and analysis methodology in the statistical analysis plan before trial unblinding

- Model specification: Use statistical regression models including main treatment effect, subgroup variable, and treatment-by-subgroup interaction term

- Covariate adjustment: Include prognostic or confounding variables in models to adjust for potential associations with outcomes

- Interaction test: Evaluate the statistical significance of the interaction term to determine if differential treatment effects exist across subgroups

- Effect estimation: If significant interaction exists, present subgroup-specific treatment effects rather than overall average effect

Protocol 2: Controlling for Multiple Testing in Subgroup Analyses

- Define testing hierarchy: Establish a pre-specified order of hypothesis tests (e.g., overall population first, then key subgroups)

- Allocate alpha: Distribute type I error rate across multiple hypotheses using appropriate multiple testing procedures

- Account for correlations: Consider using procedures that account for correlation between tests (e.g., fallback procedure) rather than Bonferroni

- Interpret results: Evaluate findings in the context of the multiple testing strategy employed

Protocol 3: Meta-Analytic Approach for Subgroup Effects Across Studies

- Data collection: Gather subgroup-specific treatment effects and standard errors from multiple studies

- Model selection: Choose appropriate meta-analytic model (fixed-effects or random-effects) based on heterogeneity assessment

- Address aggregation bias: Use methods like SWADA (Same Weighting Across Different Analyses) to resolve inconsistencies from unbalanced subgroup distributions across studies [31]

- Synthesize evidence: Calculate summary estimates for subgroup-specific treatment effects and interaction effects

- Assess heterogeneity: Evaluate between-study heterogeneity in subgroup effects using appropriate statistics (e.g., I²)

Visualization and Interpretation of Subgroup Analyses

Graphical Approaches for Subgroup Analysis

Visualization techniques play a key role in subgroup analyses to visualize effect sizes, aid identification of differentially responding groups, and communicate results [32]. Effective graphics should display treatment effect estimates, confidence intervals, subgroup sample sizes, and ideally accommodate multivariate subgroups [32].

Forest plots are the most common visualization for subgroup analyses, displaying subgroup-specific treatment effects with confidence intervals, often with symbol sizes proportional to subgroup sample sizes [30] [32]. These plots allow direct comparison of treatment effect estimates across subgroups with low cognitive effort and can display many subgroup-defining covariates [32].

Other visualization approaches include:

- Galbraith plots: Visualize standardized treatment effects against precision to identify outliers

- UpSet plots: Display intersections of multiple subgroups for multivariate analysis

- STEPP (Subpopulation Treatment Effect Pattern Plot): Explore treatment effect changes across continuous covariates

- Contour plots: Visualize treatment effects across two continuous variables simultaneously

Interpretation Guidelines

Interpreting subgroup analyses requires careful consideration of several factors:

- Biological plausibility: Are observed subgroup differences consistent with known biological mechanisms?

- Statistical evidence: Is the treatment-by-subgroup interaction statistically significant after appropriate multiple testing adjustments?

- Consistency across studies: Have similar subgroup effects been observed in independent datasets?

- Effect magnitude: Are observed differences clinically meaningful, not just statistically significant?

- Pre-specification: Were subgroup hypotheses defined a priori rather than identified through data dredging?

Figure 1: Subgroup Analysis Workflow Protocol

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Subgroup Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment-by-Subgroup Interaction Test | Determines if treatment effect differs across subgroups | Low power in typical RCTs; requires larger sample sizes for adequate detection |

| Forest Plots | Visualizes subgroup treatment effects with confidence intervals | Most effective when showing subgroup sample sizes and overall effect reference line |

| Multiple Testing Procedures | Controls false positive findings from multiple comparisons | Bonferroni is conservative; fallback and MaST procedures offer improved power |

| Random-Effects Meta-Analysis | Synthesizes subgroup effects across studies | SWADA approach addresses aggregation bias from unbalanced subgroup distributions |

| Predictive Biomarker Validation | Confirms biomarkers that predict treatment response | Requires demonstration of qualitative or quantitative interaction with treatment |

Figure 2: Subgroup Analysis Objectives and Corresponding Methods

Subgroup analyses present both opportunities and challenges in comparative drug efficacy research. When properly conducted with a priori specification, appropriate statistical methods, and careful interpretation, they can provide valuable insights into heterogeneous treatment effects and inform personalized treatment approaches. However, undisciplined subgroup analyses risk false positive findings and misleading conclusions.

Key recommendations for best practices include:

- Pre-specify subgroup hypotheses and analysis plans in the statistical analysis protocol

- Limit the number of subgroup analyses to reduce multiple testing problems

- Use appropriate statistical methods for interaction tests and multiple testing adjustments

- Ensure adequate power for subgroup analyses when they represent key study objectives