Beyond Plasma: Integrating Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) for Smarter Drug Optimization

With a 90% failure rate in clinical drug development, often due to insufficient efficacy or unmanageable toxicity, the pharmaceutical industry is re-evaluating its lead optimization paradigms.

Beyond Plasma: Integrating Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) for Smarter Drug Optimization

Abstract

With a 90% failure rate in clinical drug development, often due to insufficient efficacy or unmanageable toxicity, the pharmaceutical industry is re-evaluating its lead optimization paradigms. This article explores the critical concept of the Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR), which complements the traditional Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR). We detail how STR analysis moves beyond plasma pharmacokinetics to optimize drug exposure in disease-targeted tissues while minimizing accumulation in normal organs. Drawing on recent case studies with cannabidiol carbamates and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), we provide a methodological framework for integrating STR into drug discovery. The content covers foundational principles, practical applications, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and validation strategies, offering researchers and drug development professionals a roadmap to improve the selection of clinical candidates and balance efficacy with safety.

Why Plasma Isn't Enough: The Foundational Principles of STR

The process of clinical drug development is characterized by a persistently high failure rate, with approximately 90% of drug candidates failing to achieve regulatory approval after entering clinical trials [1]. This attrition represents a massive scientific and financial challenge, with the average cost per approved drug reaching $2.6 billion and development timelines spanning 10-15 years [2]. Analysis of clinical trial data from 2010-2017 reveals four primary reasons for this failure: lack of clinical efficacy (40-50%), unmanageable toxicity (30%), poor drug-like properties (10-15%), and lack of commercial needs or poor strategic planning (10%) [1]. Despite implementation of numerous successful strategies across target validation, screening, and preclinical testing, this 90% failure rate has remained stubbornly consistent for decades, raising critical questions about potential overlooked aspects in current drug optimization paradigms [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Clinical Attrition

Phase-by-Phase Attrition Rates

Table 1: Clinical Trial Success Rates and Durations by Phase

| Development Phase | Success Rate | Average Duration | Primary Failure Causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | 60-70% [3] | Several months to 2.3 years [3] | Safety/toxicity concerns (37% fail) [2] |

| Phase II | 30-33% [3] | Several months to 2 years [3] | Lack of efficacy (~70% fail) [2] |

| Phase III | 50-57.8% [3] | 1-4 years [3] | Inadequate efficacy/safety vs. standard of care (42% fail) [2] |

| Overall (Phase I to Approval) | ~10% [1] | 6-7 years (clinical phase only) [3] | Efficacy (40-50%), toxicity (30%), PK/PD properties (10-15%) [1] |

Dynamic Success Rate Analysis

Recent analyses indicate that while clinical trial success rates (ClinSR) declined since the early 21st century, they have recently plateaued and begun to show slight improvement [4]. The ClinSR for repurposed drugs has been unexpectedly lower than that for all drugs in recent years, with anti-COVID-19 drugs demonstrating an extremely low ClinSR [4]. Significant variations exist in ClinSRs across different disease areas, developmental strategies, and drug modalities, highlighting the need for therapeutic-area-specific development strategies.

The STAR Framework: Addressing Fundamental Gaps in Drug Optimization

Limitations of Current Optimization Approaches

Current drug optimization overwhelmingly emphasizes potency and specificity using structure-activity relationship (SAR) but largely overlooks tissue exposure and selectivity in disease versus normal tissues [1] [5]. This imbalance misleads drug candidate selection and critically impacts the balance of clinical dose, efficacy, and toxicity. The standard practice of using plasma exposure as a surrogate for tissue exposure represents a significant flaw, as studies demonstrate that drug plasma exposure frequently does not correlate with drug exposure in target tissues [6]. For central nervous system targets, this discrepancy is particularly problematic, as candidates with adequate plasma levels may fail to achieve therapeutic concentrations in required tissues.

Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity-Activity Relationship (STAR)

The STAR framework proposes a integrated approach that classifies drug candidates based on three key parameters: drug potency/selectivity, tissue exposure/selectivity, and required dose for balancing clinical efficacy/toxicity [1]. This classification system enables more informed candidate selection and development strategy:

Table 2: STAR-Based Drug Candidate Classification

| Class | Potency/Specificity | Tissue Exposure/Selectivity | Clinical Dose | Success Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Low | Superior clinical efficacy/safety with high success rate |

| Class II | High | Low | High | Achieves efficacy with high toxicity; requires cautious evaluation |

| Class III | Relatively low (adequate) | High | Low | Achieves efficacy with manageable toxicity; often overlooked |

| Class IV | Low | Low | High | Inadequate efficacy/safety; should be terminated early |

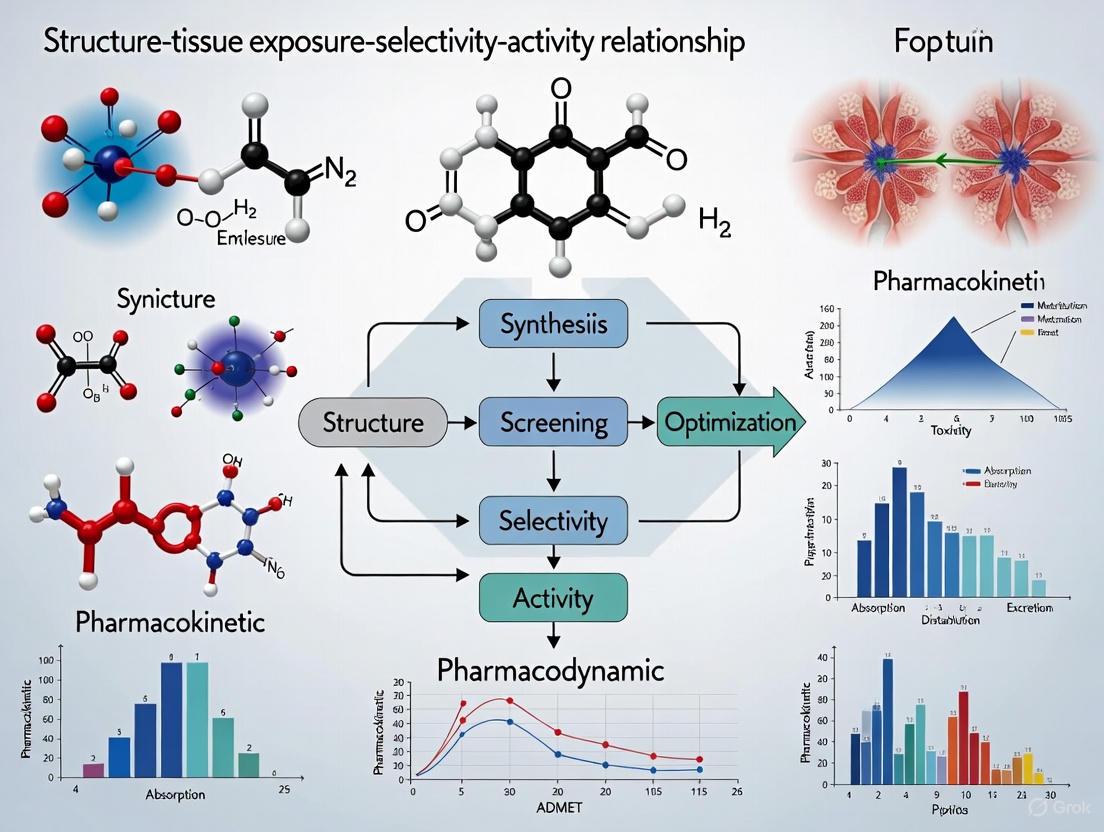

Diagram 1: Integrated STAR Framework for Drug Optimization

Experimental Protocols for STR Assessment

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Tissue Distribution Study

Objective: To quantitatively determine drug exposure and selectivity in disease-targeted tissues versus normal tissues.

Materials:

- Test compound(s) and reference standards

- Animal disease models (minimum n=6 per group)

- UPLC-HRMS system with validated analytical method

- Tissue homogenization equipment

- Isotope-labeled internal standards

Methodology:

- Dosing and Sample Collection: Administer therapeutic dose orally or intravenously. Euthanize animals at predetermined time points (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24h). Collect blood (for plasma), disease-target tissues, and vital normal tissues.

- Sample Processing: Homogenize tissues in appropriate buffer (1:3 w/v). Extract drugs using protein precipitation (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) with isotope-labeled internal standards.

- UPLC-HRMS Analysis:

- Column: Acquity UPLC BEH C18 (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm)

- Mobile phase: A: 0.1% formic acid in water; B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient elution: 5-95% B over 3.5 min, flow rate 0.4 mL/min

- MS detection: Positive/negative electrospray ionization, full scan mode (m/z 100-1000)

- Data Analysis: Calculate tissue-to-plasma ratios (Kp) for each tissue. Determine AUC0-t in plasma and tissues using non-compartmental analysis. Compute tissue selectivity index (TSI) as AUCdisease tissue/AUCnormal tissue.

Validation Parameters:

- Extraction recovery: >85%

- Matrix effects: 85-115%

- Precision: CV <15%

- Accuracy: 85-115% of nominal values

Protocol 2: STR Correlation with Efficacy/Toxicity

Objective: To establish correlation between tissue exposure/selectivity and observed efficacy/toxicity endpoints.

Materials:

- Series of structurally related compounds (minimum 4 analogs)

- Disease-relevant efficacy models

- Histopathology equipment

- Clinical chemistry analyzers

Methodology:

- Parallel Efficacy/Toxicity Testing: Conduct efficacy studies in disease models using standardized dosing regimens. In parallel, perform acute toxicity studies with MTD determination.

- Tissue Exposure Mapping: Quantify drug concentrations in efficacy-related tissues and toxicity-related tissues at multiple time points.

- Correlative Analysis:

- Plot efficacy endpoints (e.g., tumor reduction, biomarker modulation) against tissue AUC values

- Plot toxicity endpoints (e.g., histopathology scores, clinical chemistry) against tissue AUC values

- Calculate therapeutic windows based on tissue exposure rather than plasma exposure

- STR Modeling: Use molecular descriptors (logP, polar surface area, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors) to build quantitative STR models predicting tissue distribution patterns.

Research Reagent Solutions for STR Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for STR Investigation

| Reagent/Technology | Function in STR Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| UPLC-HRMS Systems | Simultaneous quantification of drugs and metabolites in tissues with high sensitivity | Tissue distribution studies, metabolite profiling [6] |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Validate target engagement in intact cells and tissues | Confirmation of mechanism of action in disease-relevant tissues [7] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Improve quantitative accuracy in complex matrices | Normalize extraction efficiency and matrix effects in tissue analysis [6] |

| AI/ML Prediction Platforms | In silico prediction of tissue distribution and selectivity | Early screening of compound libraries for favorable STR [8] |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | High-throughput screening of compound-target interactions | Identify hits with optimal binding characteristics [9] |

| Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling Software | Simulate tissue distribution prior to in vivo studies | Predict STR and optimize compound selection [2] |

Implementation Workflow for STAR-Driven Optimization

Diagram 2: STAR-Driven Drug Candidate Selection Workflow

The persistent 90% clinical attrition rate represents both a fundamental scientific challenge and substantial economic burden for drug development. The integrated STAR framework addresses core limitations of current optimization approaches by balancing traditional potency-focused SAR with critically important tissue exposure/selectivity considerations. Implementation of the experimental protocols and classification system described in this Application Note enables systematic identification of Class I drug candidates with optimal tissue distribution profiles, potentially reversing the trend of high clinical failure rates. As drug discovery continues to evolve, incorporating STR considerations early in the optimization process will be essential for developing therapeutics with balanced efficacy and safety profiles.

The "Free Drug Hypothesis" has long been a guiding principle in pharmacology, positing that only the unbound drug fraction in plasma passively distributes into tissues, with free drug concentrations at steady-state being approximately equal between plasma and target tissues [10]. This concept has profoundly influenced drug candidate selection, favoring compounds with high plasma exposure. However, mounting evidence reveals critical limitations of this model, as drug exposure in the plasma frequently fails to predict exposure in disease-targeted tissues [10] [6]. This discrepancy often misguides drug candidate selection, contributing to the high failure rates (approximately 90%) observed in clinical drug development [10] [6].

The emerging concept of the Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) provides a more nuanced framework for drug optimization [10] [6]. STR investigates how structural modifications to a drug molecule influence its distribution and selectivity between target and normal tissues, directly impacting the balance between clinical efficacy and toxicity [10]. This article details application notes and protocols for characterizing these tissue exposure disparities, providing methodologies essential for integrating STR analysis into modern drug development pipelines.

Quantitative Evidence: Documented Disconnects Between Plasma and Tissue Exposure

Evidence from Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs)

A systematic investigation of seven SERMs with similar structures and identical molecular targets demonstrated that plasma drug exposure (AUC) did not correlate with drug concentrations in key target tissues, including tumor, fat pad, bone, and uterus [10]. The study found that slight structural modifications of four different SERMs did not significantly alter their plasma exposure profiles but profoundly altered their tissue exposure and selectivity [10]. This tissue-level distribution was directly correlated with the distinct clinical efficacy and safety profiles observed for these compounds.

Evidence from Cannabidiol (CBD) Carbamates

Research on BuChE-targeted CBD carbamates further underscores this phenomenon. In a study of CBD carbamates L2 and L4, the two compounds showed similar plasma exposure profiles but dramatically different distributions in the target tissue (brain) [6]. Specifically, L2 exhibited a fivefold higher brain concentration than L4, despite their nearly identical plasma AUC values [6]. This finding is particularly critical for central nervous system (CNS) drug development, where brain tissue exposure, not plasma concentration, determines pharmacodynamic activity.

Table 1: Comparative Tissue Exposure of Drug Candidates with Similar Plasma PK

| Drug Candidate | Plasma AUC (h·ng/mL) | Target Tissue AUC (h·ng/mL) | Tissue-to-Plasma Ratio (Kp) | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERM A | ~1000 (Reference) | Tumor: ~800 | ~0.8 | Efficacy: Low |

| SERM B | ~1000 (Reference) | Tumor: ~2500 | ~2.5 | Efficacy: High |

| CBD Carbamate L2 | ~1000 (Reference) | Brain: ~5000 | ~5.0 | Efficacy: High |

| CBD Carbamate L4 | ~1000 (Reference) | Brain: ~1000 | ~1.0 | Efficacy: Low |

Core Experimental Protocols for Assessing Tissue Exposure and Selectivity

Comprehensive Tissue Distribution Study Protocol (LC-MS/MS Based)

Application Note: This protocol provides a robust methodology for quantifying drug concentrations across multiple tissues simultaneously, enabling the construction of detailed STR profiles. The method is particularly valuable for comparing analogs with similar plasma PK but potential differences in tissue distribution.

Materials and Reagents:

- Test compounds (drug candidates)

- Female MMTV-PyMT mice (8-12 weeks old) or other relevant disease models

- LC-MS/MS system with appropriate analytical column

- Acetonitrile (LC-MS grade)

- Internal standard solution (e.g., 25 nmol/L CE302 in ACN)

- Tissue homogenization equipment

Experimental Workflow:

Procedure Details:

- Animal Dosing: Administer test compounds at pharmacologically relevant doses (e.g., 5 mg/kg p.o. or 2.5 mg/kg i.v. for SERMs) to appropriate animal models [10].

- Time-Staggered Sample Collection: Euthanize animals at predetermined time points (e.g., 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 7 hours post-dosing) to capture distribution and elimination phases [10].

- Comprehensive Tissue Harvesting: Collect blood (for plasma separation), disease-targeted tissues (e.g., tumors for oncology models, brain for CNS targets), and potential toxicity-related normal tissues (e.g., liver, kidney, heart) [10].

- Sample Processing: Homogenize tissue samples in ice-cold acetonitrile containing an internal standard (40 μL sample + 40 μL ACN + 120 μL IS) [10]. Vortex for 10 minutes followed by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C to precipitate proteins [10].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Inject supernatant for quantification using validated methods. Monitor multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions specific to each compound.

- Data Analysis: Calculate AUC values for plasma and each tissue using non-compartmental methods. Determine tissue-to-plasma distribution coefficients (Kp = AUCtissue/AUCplasma) and tissue selectivity indices (SI = AUCtarget/AUCnormal).

Fluorescence-Based Biodistribution Quantification Protocol

Application Note: This protocol offers an alternative quantification method for fluorescently labeled compounds, enabling simultaneous tracking of multiple agents and providing spatial distribution information within tissues. It is particularly valuable for paired-agent imaging applications.

Materials and Reagents:

- Fluorescent agents (e.g., ABY-029, IRDye 680LT)

- Borosilicate glass capillary tubes

- Wide-field fluorescence imaging system

- Tissue homogenizer

- Nude mice with xenograft tumors (e.g., FaDu cells)

Experimental Workflow:

Procedure Details:

- Tissue-Specific Calibration Curves: Generate separate calibration curves for each tissue type by spiking known concentrations of fluorescent agents into homogenized tissue matrices. This accounts for tissue-specific optical properties and quenching effects [11].

- Agent Administration: Co-administer targeted and untargeted fluorescent agents via tail vein injection (e.g., 0.0487 mg/kg ABY-029 with equimolar IRDye 680LT in 200 μL PBS) [11].

- Sample Collection and Processing: Collect blood and tissues at multiple time points. Homogenize tissues thoroughly and load homogenates along with whole blood into borosilicate glass capillary tubes to standardize path length [11].

- Fluorescence Imaging and Quantification: Image capillary tubes using a wide-field fluorescence imaging system. Convert mean fluorescence intensity to concentration using tissue-specific calibration curves, which typically show high linearity (R² = 0.99 ± 0.01) [11].

- Data Analysis: Calculate pharmacokinetic parameters and biodistribution profiles for each agent. For paired-agent imaging, compare targeted and untargeted agent kinetics to estimate receptor concentration [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for STR Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Application Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS/MS System | Quantitative drug measurement in complex matrices | Enables multiplexed quantification of parent drug and metabolites |

| Wide-field Fluorescence Imager | Fluorescent agent biodistribution | Must standardize path length (e.g., capillary tubes) for accuracy [11] | |

| Biological Models | MMTV-PyMT Transgenic Mice | Spontaneous breast cancer model | Allows study of tissue distribution in relevant disease context [10] |

| FaDu Xenograft Models | Head and neck cancer model | Useful for targeted agent studies (e.g., EGFR-targeting ABY-029) [11] | |

| Critical Reagents | CBD Carbamates (L1-L4) | STR probe compounds for CNS targets | Demonstrate how slight structural changes alter brain distribution [6] |

| Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators | STR probe compounds for oncology | Show tissue selectivity despite similar plasma PK [10] | |

| IRDye 680LT & ABY-029 | Fluorescent paired agents | Enable comparative biodistribution and receptor quantification [11] | |

| Sample Processing | Internal Standards (e.g., CE302) | Normalization of extraction efficiency | Critical for accurate LC-MS/MS quantification [10] |

| Borosilicate Capillary Tubes | Standardized fluorescence measurement | Control path length variability in heterogeneous samples [11] | |

| PZ-II-029 | PZ-II-029, CAS:164025-44-9, MF:C18H15N3O3, MW:321.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| QX77 | QX77, MF:C16H13ClN2O2, MW:300.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Data Analysis and STR Modeling Approaches

Calculation of Key Distribution Parameters

- Tissue-to-Plasma Distribution Coefficient (Kp): Kp = AUCtissue / AUCplasma

- Tissue Selectivity Index (SI): SI = AUCtargettissue / AUCtoxicitytissue

- Relative Exposure Ratio (RER): RER = KpanalogA / KpanalogB

Multivariate Analysis for STR

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces dimensionality of multi-tissue distribution data to identify clustering patterns among structural analogs [10].

- Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Modeling: Builds quantitative structure-distribution relationship models to predict tissue exposure based on molecular descriptors [10].

Integration with ADMET Profiling

Correlate tissue distribution data with in silico ADMET predictions, including:

- Acute oral toxicity (LD50) projections

- Plasma protein binding propensity

- Blood-brain barrier permeability

- Hepatotoxicity risk indices [6]

Table 3: Integrating STR with ADMET Profiles for Candidate Selection

| Compound | Brain Kp | Plasma AUC | Predicted LD₅₀ (mg/kg) | BuChE IC₅₀ (μM) | STR-Based Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBD | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 319.5 | >10 | High safety, low potency |

| L1 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 22.1 | 0.15 | Toxicity concern |

| L2 | 5.0 | 3.2 | 70.5 | 0.077 | Optimal profile |

| L3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 80.0 | 0.18 | Low brain exposure |

| L4 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 84.0 | 0.025 | High potency, low brain delivery |

The presented application notes and protocols provide a systematic approach for challenging the Free Drug Hypothesis and implementing STR analysis in drug discovery. By moving beyond plasma-centric pharmacokinetic evaluation to comprehensive tissue distribution assessment, researchers can:

- Select drug candidates based on target tissue exposure rather than plasma levels

- Optimize structural features to enhance tissue selectivity and improve therapeutic index

- Identify potential toxicity risks from unintended tissue accumulation early in development

- Rationalize clinical efficacy/toxicity outcomes through understanding of tissue-specific distribution

Integrating these STR methodologies with traditional SAR and ADMET profiling creates a more holistic drug optimization framework that can significantly improve clinical success rates by ensuring adequate drug exposure at the site of action while minimizing off-target accumulation.

The Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) is a critical concept in modern drug optimization that describes how structural modifications to a lead compound alter its distribution and concentration in specific tissues relative to plasma and other tissues [10]. Traditional drug optimization has heavily emphasized the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR), which focuses on improving a drug's potency and specificity for its molecular target, and drug-like properties based primarily on plasma pharmacokinetics (PK) [10]. However, this approach often overlooks a compound's tissue exposure/selectivity, which can directly impact clinical efficacy and toxicity profiles [10] [6].

The fundamental hypothesis underlying STR is that drug exposure in plasma is not always a reliable surrogate for drug exposure in disease-targeted tissues [10] [6]. Selecting drug candidates based solely on high plasma exposure can be misleading, as some compounds with low plasma exposure may achieve high concentrations in target tissues, and vice-versa [10]. Furthermore, even slight structural modifications that have minimal impact on plasma PK can significantly alter a drug's distribution profile, thereby affecting the balance between clinical efficacy and safety [10] [6]. Optimizing the STR, therefore, involves structural design to maximize drug exposure in diseased tissues while minimizing accumulation in healthy, toxicity-prone organs [6].

Quantitative Evidence of STR

STR in Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs)

A foundational study investigating seven SERMs with similar structures and the same molecular target demonstrated that their tissue exposure and selectivity were correlated with clinical efficacy/safety, whereas plasma exposure was not [10]. The following table summarizes key experimental findings from this research.

Table 1: Experimental Tissue Distribution Data of Select SERMs in MMTV-PyMT Mice (2.5 mg/kg i.v.) [10]

| Tissue | Tamoxifen AUC (ng·h/mL) | Toremifene AUC (ng·h/mL) | Afimoxifene AUC (ng·h/mL) | Droloxifene AUC (ng·h/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | 240.5 | 255.8 | 248.9 | 235.2 |

| Tumor | 12,450.0 | 10,580.0 | 9,850.0 | 8,950.0 |

| Bone | 1,250.5 | 1,150.8 | 980.5 | 850.3 |

| Uterus | 890.3 | 950.6 | 1,050.7 | 780.4 |

| Liver | 15,850.0 | 14,950.0 | 16,050.0 | 12,500.0 |

Key Observations:

- Plasma-Tissue Disconnect: SERMs with nearly identical plasma exposure (AUC) showed markedly different accumulation in target tissues like tumors and bones [10].

- Efficacy/Toxicity Correlation: Tissue exposure/selectivity, not plasma levels, aligned with the distinct clinical efficacy and safety profiles of the SERMs [10].

- Structural Impact: Slight structural modifications among the SERMs were sufficient to alter their tissue exposure/selectivity, underscoring the existence of a definable STR [10].

STR in Cannabidiol (CBD) Carbamates

Recent research on CBD carbamates further validates the STR concept for central nervous system (CNS) targets. The study compared two carbamate derivatives, L2 and L4, which have similar plasma exposure but different structures at the carbamate amine group [6].

Table 2: Comparative STR Analysis of CBD Carbamates L2 and L4 [6]

| Parameter | L2 (Methylethylamine) | L4 (tert-Benzylamine) |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma AUC | High and similar to L4 | High and similar to L2 |

| Brain AUC | 5x higher than L4 | 5x lower than L2 |

| BuChE IC₅₀ | 0.077 μM | More potent than L2 |

| Rat LDâ‚…â‚€ | 70.5 mg/kg | 84.0 mg/kg |

| Key STR Insight | High brain penetration, favorable for CNS efficacy. | Lower brain exposure despite high plasma levels and high potency. |

Key Observations:

- The similar plasma exposure of L2 and L4 would not predict their drastically different brain distribution [6].

- The tissue/plasma distribution coefficient (Kp) is a critical STR parameter. Drug exposure in tissue is calculated as: Drug exposure in tissue = Drug exposure in plasma × Kp [6].

- This case demonstrates that STR optimization for CNS drugs requires a specific focus on ensuring sufficient brain exposure, independent of plasma PK [6].

Experimental Protocol for STR Profiling

This protocol details the methodology for quantifying tissue distribution to establish a Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) for lead compounds, adapted from published studies [10] [6].

Materials and Reagents

- Test Compounds: Lead compounds and their structurally modified analogs.

- Animal Model: Disease-relevant animal model (e.g., transgenic MMTV-PyMT mice for breast cancer [10] or wild-type/transgenic rats for CNS studies [6]).

- Vehicle: Appropriate solvent for compound administration (e.g., saline, aqueous solution with <5% DMSO or other solubilizing agents).

- LC-MS/MS Materials:

- Mobile Phases: Acetonitrile and water of LC-MS grade.

- Internal Standard Solution: Stable isotope-labeled analog of the test compound or a structurally similar compound (e.g., CE302 at 25 nmol/L in ACN [10]).

- UPLC-HRMS System: Equipped with a C18 reverse-phase column.

In Vivo Tissue Distribution Study

Dosing and Sample Collection:

- Administer the test compound to animals (e.g., via oral gavage or intravenous injection) at a predefined dose (e.g., 5 mg/kg p.o. or 2.5 mg/kg i.v.) [10].

- At predetermined time points post-dosing (e.g., 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 7 hours), euthanize a cohort of animals and collect samples of blood/plasma and all tissues of interest (e.g., disease-targeted tissue, potential toxicity organs, and other relevant tissues) [10].

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize weighed tissue samples in a buffer solution.

- Aliquot a precise volume (e.g., 40 μL) of plasma, blood, or tissue homogenate into a 96-well plate.

- Add ice-cold acetonitrile (e.g., 40 μL) and internal standard solution (e.g., 120 μL) to precipitate proteins and extract the analyte [10].

- Vortex the mixture vigorously for 10 minutes and then centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 3500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C) to remove precipitated material [10].

Bioanalysis via LC-MS/MS:

- Inject an aliquot of the supernatant into the UPLC-HRMS system.

- Quantify the concentration of the test compound in each sample by comparing the analyte-to-internal standard response ratio against a freshly prepared calibration curve.

Data Analysis and STR Modeling

Pharmacokinetic Calculation:

- Use a non-compartmental analysis (e.g., using Phoenix WinNonlin) to calculate the Area Under the concentration-time Curve (AUC) for plasma and each tissue.

Tissue Distribution Parameters:

- Calculate the Tissue-to-Plasma Ratio (Kp) for each tissue:

Kp = AUC_tissue / AUC_plasma. - Calculate the Tissue Selectivity Index (TSI) between target and toxicity-prone tissues:

TSI = Kp_target / Kp_toxicity.

- Calculate the Tissue-to-Plasma Ratio (Kp) for each tissue:

STR Correlation:

- Corrogate the structural features of each analog (e.g., logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds, presence of specific heterocycles [12]) with its tissue exposure (AUC_tissue) and selectivity (Kp, TSI).

- Use statistical models like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) to define the quantitative STR [10].

Workflow Visualization for STR-Driven Drug Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for applying STR in lead optimization.

Diagram Title: STR-Driven Lead Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for STR Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Ensures accurate and precise quantification of drug concentrations in complex biological matrices (plasma, tissue homogenates) by correcting for variability during sample preparation and MS ionization. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (acetonitrile, water, methanol) minimize background noise and ion suppression in LC-MS/MS, which is critical for detecting low drug levels in small tissue samples. |

| Disease-Relevant Animal Model | Transgenic or xenograft models that replicate human disease pathophysiology are essential for generating clinically translatable STR data, as tissue distribution can be altered by the disease state (e.g., tumor EPR effect [10]). |

| Physicochemical & ADMET Prediction Software | Tools used to predict key properties (logP, pKa, TPSA) that influence tissue penetration early in the design cycle, helping to prioritize analogs for synthesis and in vivo testing [12] [6]. |

| UPLC-HRMS System | Provides the high chromatographic resolution and mass accuracy needed to separate, identify, and quantify the drug and its potential metabolites in tissue samples, ensuring data reliability. |

| Relmapirazin | Relmapirazin (MB-102) |

| RG7800 | RG7800|SMN2 Splicing Modulator|For Research |

Integrating STR analysis into the lead optimization pipeline is no longer optional for modern drug development. Evidence from SERMs and CBD carbamates confirms that structural modifications which minimally affect plasma exposure can drastically alter tissue distribution and selectivity [10] [6]. By employing the described protocols to generate quantitative tissue PK data and define the STR, researchers can make more informed candidate selection decisions. This approach moves beyond the traditional over-reliance on plasma PK and SAR, enabling the design of molecules optimized for high exposure at the site of action and low exposure in sites of potential toxicity, thereby increasing the probability of clinical success.

In the rigorous process of drug discovery, the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) has long been the cornerstone of lead optimization, focusing primarily on improving a drug candidate's potency and specificity against its molecular target [10]. However, an overemphasis on SAR often overlooks a critical determinant of clinical success: how structural modifications influence a drug's distribution to diseased tissues versus healthy ones. This relationship, termed the Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR), is now recognized as equally vital for balancing clinical efficacy with toxicity [6] [13].

The high failure rate of clinical drug development (approximately 90%) is often attributed to insufficient efficacy (~40-50%) or unmanageable toxicity (~30%) [10] [13]. A significant contributing factor is that the current drug optimization process frequently selects candidates based on high plasma exposure and target potency in vitro, mistakenly assuming this correlates with effective exposure in disease-targeted tissues [6] [10]. The Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) framework has been proposed to integrate these concepts, classifying drug candidates based on both their potency/selectivity and their tissue exposure/selectivity to better predict clinical outcomes [13].

This application note provides experimental protocols and analytical frameworks for characterizing STR and integrating it with SAR data, enabling a more balanced and predictive approach to drug candidate selection.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Table 1: Core Concepts in Integrated Drug Optimization

| Concept | Acronym | Definition | Primary Optimization Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Activity Relationship | SAR | The relationship between a compound's chemical structure and its biological activity against a specific molecular target. | Maximize target potency and specificity. |

| Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship | STR | The relationship between a compound's chemical structure and its relative distribution and concentration in different tissues, particularly disease-targeted vs. normal tissues. | Maximize exposure in target tissues and minimize exposure in tissues associated with toxicity. |

| Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity–Activity Relationship | STAR | An integrated framework that combines SAR and STR to classify drug candidates and guide selection based on potency, selectivity, tissue exposure, and required clinical dose. | Balance efficacy, toxicity, and dose to improve clinical success rates [13]. |

Table 2: STAR Classification System for Drug Candidates

| Class | Specificity/Potency | Tissue Exposure/Selectivity | Clinical Dose Implication | Clinical Outcome & Success Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Low dose required. | Superior efficacy/safety profile; high success rate [13]. |

| Class II | High | Low | High dose required. | Efficacy possible but with high toxicity risk; requires cautious evaluation [13]. |

| Class III | Relatively Low (Adequate) | High | Low dose required. | Good clinical efficacy with manageable toxicity; often overlooked in traditional optimization [13]. |

| Class IV | Low | Low | N/A | Inadequate efficacy and safety; should be terminated early [13]. |

Experimental Protocol for STR Characterization

Protocol: Comparative Tissue Distribution Study

Objective: To determine the tissue exposure and selectivity of drug candidates following administration in a relevant animal model.

I. Materials and Reagents Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Catalog Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Test Compounds | Drug candidates for STR assessment. | e.g., CBD carbamates L1-L4 [6]; SERMs like tamoxifen, toremifene [10]. |

| Animal Model | In vivo system for pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution studies. | e.g., Rats (for CBD carbamates); Female MMTV-PyMT mice (for SERM studies in breast cancer) [6] [10]. |

| UPLC-HRMS or LC-MS/MS System | Quantitative bioanalysis of drug concentrations in biological matrices. | Systems capable of sensitive, simultaneous compound quantification (e.g., ACQUITY UPLC with Q-Exactive HRMS; LC-MS/MS with triple quadrupole) [6] [10]. |

| Internal Standard | Correction for sample preparation and injection variability in MS analysis. | Stable isotope-labeled analog of the analyte or structurally similar compound (e.g., CE302 for SERM analysis) [10]. |

| Protein Precipitation Solvent | Deproteinization of plasma and tissue homogenates for cleaner MS analysis. | Ice-cold acetonitrile [10]. |

II. Procedure

Formulation and Dosing:

Biological Sample Collection:

- At predetermined time points post-dosing (e.g., 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 7 h), collect blood/plasma and relevant tissues.

- Target Tissues: Disease-relevant organs (e.g., brain for CNS disorders, tumor for oncology).

- Normal Tissues: Organs where toxicity often manifests (e.g., liver, heart, uterus for SERMs) [6] [10].

- Centrifuge blood to obtain plasma. Homogenize tissue samples in an appropriate buffer.

Sample Preparation:

- Aliquot a measured volume of plasma or tissue homogenate (e.g., 40 μL) into a 96-well plate.

- Add ice-cold acetonitrile (e.g., 40 μL) containing an internal standard to precipitate proteins.

- Vortex the mixture vigorously for 10 minutes and then centrifuge (e.g., 3500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C) to pellet debris [10].

- Transfer the clear supernatant for analysis.

Bioanalysis using UPLC-HRMS/LC-MS/MS:

- Inject the processed samples onto the chromatographic system.

- Use a validated method to separate the analytes.

- Detect compounds using mass spectrometry. Quantify concentrations by comparing the analyte-to-internal standard response ratio against a calibration curve prepared in the same biological matrix [6] [10].

Data Analysis:

- Use non-compartmental methods to calculate pharmacokinetic parameters: Area Under the Curve (AUC) for plasma (AUC~plasma~) and for each tissue (AUC~tissue~).

- Calculate the Tissue-to-Plasma Partition Coefficient (K~p~) for each tissue: K~p~ = AUC~tissue~ / AUC~plasma~ [6].

- Determine Tissue Selectivity Indices by comparing K~p~ values between target and off-target tissues (e.g., Brain-to-Liver K~p~ ratio).

Diagram 1: Tissue distribution study workflow.

Case Study: STR in Action – CBD Carbamates

Background: A series of cannabidiol (CBD) carbamates (L1-L4) were designed as potent butyrocholinesterase (BuChE) inhibitors for potential application in Alzheimer's disease, targeting the central nervous system [6].

Experimental Data: Table 4: STR Analysis of CBD Carbamates (Representative Data) [6]

| Compound | Key Structural Feature (Carbamate Amine) | BuChE IC₅₀ (μM) | Relative Plasma AUC | Relative Brain AUC | Brain-to-Plasma K~p~ | Rat Oral LD₅₀ (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L0 (CBD) | N/A | >10 | 1.0 | 1.0 | Baseline | 319.5 |

| L1 | Secondary Aliphatic Amine | ~0.1 | Low | Low | Low | 22.1 |

| L2 | Methylethylamine (Tertiary Aliphatic) | 0.077 | High | Very High | High | 70.5 |

| L3 | Cyclic Amine | ~0.1 | Low | Low | Low | 80.0 |

| L4 | tert-Benzylamine (Tertiary Aromatic) | Most Potent | High | Moderate | Moderate | 84.0 |

STR Interpretation and STAR Classification:

- Impact of Structure: Slight modifications to the carbamate amine group (e.g., secondary vs. tertiary, aliphatic vs. cyclic/aromatic) resulted in significant changes in tissue exposure and selectivity, independent of changes in plasma exposure or in vitro potency [6]. For instance, L2 and L4 had similar high plasma exposure, but L2 exhibited a 5-fold higher brain concentration than L4 [6].

- Efficacy/Safety Correlation: The secondary amine of L1 was metabolically less stable and associated with significantly higher oral toxicity (lower LDâ‚…â‚€), whereas the tertiary amines (L2, L3, L4) were more stable and had better safety profiles [6].

- STAR Classification:

- L2 demonstrates high BuChE potency and high brain exposure/selectivity, making it a potential Class I drug requiring a low dose for efficacy.

- L4 has high potency but lower brain selectivity than L2, potentially placing it in Class II, where a higher dose might be needed for efficacy, possibly increasing toxicity risk.

- L1 and L3, despite reasonable potency, have low plasma and tissue exposure, rendering them Class IV candidates.

Diagram 2: SAR and STR relationship in CBD carbamates.

Integrating STR and SAR: The STAR Framework for Candidate Selection

The CBD carbamate case and similar studies with Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) [10] underscore that drug exposure in plasma is not a reliable surrogate for exposure in target tissues [6] [10]. Therefore, lead optimization must move beyond a singular focus on plasma PK and in vitro potency.

Protocol: Integrated STAR Analysis Workflow

- In Vitro Potency & Specificity Profiling (SAR): Determine ICâ‚…â‚€/Káµ¢ values against the primary target and related off-targets.

- In Vivo Tissue Distribution Study (STR): Conduct the protocol outlined in Section 3 to calculate AUC~plasma~, AUC~tissue~, and K~p~ values for key tissues.

- Toxicity Assessment: Perform preliminary in vivo toxicity studies (e.g., maximum tolerated dose, LDâ‚…â‚€, histopathology) [6].

- STAR Matrix Plotting and Classification:

- Create a 2D plot with Target Potency (e.g., 1/ICâ‚…â‚€) on the Y-axis and Tissue Selectivity Index (e.g., Target Tissue K~p~ / Toxic Tissue K~p~) on the X-axis.

- Overlay data points for all lead candidates.

- Classify each candidate into one of the four STAR classes (see Table 2).

- Candidate Selection:

- Prioritize Class I candidates for further development.

- Critically evaluate and potentially optimize Class II candidates to improve tissue selectivity.

- Re-evaluate Class III candidates that may have been overlooked by traditional SAR-focused optimization; their high tissue selectivity may allow for efficacy despite moderate in vitro potency.

- Terminate Class IV candidates early.

Table 5: Decision Matrix for STAR-Based Candidate Selection

| STAR Class | Development Recommendation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Class I | High Priority for Progression | Ideal profile. Focus on formulation and preclinical safety. |

| Class II | Proceed with Caution / Optimize | Attempt structural modification to improve tissue selectivity (STR). Evaluate therapeutic index rigorously. |

| Class III | Re-evaluate and Consider | Often discarded by traditional methods. Assess if in vivo efficacy is adequate despite modest in vitro potency. Promising for low-dose therapies. |

| Class IV | Terminate | Unlikely to achieve a favorable efficacy-toxicity balance. |

Integrating the Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) with the classical Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) into a unified STAR framework provides a more holistic and predictive approach to drug optimization. The experimental protocols and analytical tools outlined in this application note empower researchers to systematically characterize and leverage STR. By selecting drug candidates based on both their intrinsic potency and their ability to selectively reach the site of action while avoiding healthy tissues, the probability of achieving a successful balance between clinical efficacy and safety in later-stage trials is significantly enhanced [6] [10] [13].

The Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity relationship (STR) has emerged as a critical factor in drug development, demonstrating that minimal molecular modifications can significantly alter a compound's distribution profile across different tissues, ultimately impacting clinical efficacy and safety. This case study examines how subtle structural changes in Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) result in dramatic alterations in tissue exposure and selectivity, independent of plasma pharmacokinetics. Through quantitative analysis of tissue distribution patterns and detailed experimental protocols, we provide a framework for integrating STR assessment into standard drug optimization workflows to improve clinical candidate selection and therapeutic outcomes.

Traditional drug optimization has heavily emphasized Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) to enhance potency and specificity against molecular targets. However, this approach often overlooks the critical Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity relationship (STR), which directly influences a drug's efficacy and toxicity profile in different tissues [14] [5]. The STR paradigm investigates how structural modifications affect a compound's distribution between disease-targeted tissues and normal tissues, creating tissue-selective exposure profiles that cannot be predicted from plasma pharmacokinetics alone [15].

Research on seven SERMs with similar structures and the same molecular target revealed that drug plasma exposure showed no correlation with drug exposures in key target tissues including tumor, fat pad, bone, and uterus [14] [5]. This disconnect underscores the necessity of directly measuring tissue exposure during drug development rather than relying on plasma concentrations as surrogates for target engagement.

Quantitative Analysis of SERM Tissue Distribution

Tissue Exposure Profiles Across SERM Classes

Table 1: Comparative Tissue Distribution Profiles of Representative SERMs

| SERM | Key Structural Features | Tumor Exposure | Bone Exposure | Uterine Exposure | Clinical Efficacy/Safety Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen | Triphenylethylene core | Moderate | Moderate | High | Breast cancer efficacy; increased endometrial cancer risk |

| Raloxifene | Benzothiophene core | Moderate | High | Low | Osteoporosis treatment; breast cancer risk reduction |

| Fulvestrant | Steroidal backbone, 7α-alkyl sulfinyl chain | High | Low | Low | ER degradation; treatment of advanced breast cancer |

| Bazedoxifene | Indole core | Moderate | High | Low | Menopausal symptoms; osteoporosis prevention |

| Lasofoxifene | Naphthalene core | High | High | Moderate | Osteoporosis treatment; breast cancer risk reduction |

Impact of Minor Structural Modifications on Tissue Exposure

Studies investigating four SERMs with slight structural modifications demonstrated that these changes did not significantly alter plasma exposure but profoundly affected tissue exposure and selectivity [14] [5]. For instance, the replacement of a single atom in the tamoxifen structure to create toremifene resulted in altered tissue distribution patterns despite similar plasma pharmacokinetics [16].

Table 2: Impact of Specific Structural Modifications on SERM Tissue Distribution

| Structural Modification | Plasma Exposure Change | Tumor Tissue Impact | Bone Tissue Impact | Uterine Tissue Impact | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side chain length variation | Minimal | Up to 3.2-fold change | Up to 2.8-fold change | Up to 4.1-fold change | Altered efficacy/toxicity balance |

| Hydrogen bond donor/acceptor changes | Minimal | Significant alterations in accumulation | Variable effects | Pronounced changes | Modified tissue selectivity |

| Halogen substitution | Minimal | Altered penetration | Moderate effects | Significant impact | Safety profile modification |

| Protein binding affinity modifications | Minimal | Enhanced tumor accumulation via EPR effect | Limited effect | Limited effect | Improved tumor targeting |

Molecular Mechanisms of SERM Tissue Selectivity

Structural Biology of Estrogen Receptor Modulation

SERMs produce tissue-specific effects by inducing distinct conformational changes in estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), which are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-dependent transcription factors [17] [18]. The ER ligand-binding domain (LBD) consists of 12 alpha helices that rearrange differently depending on the specific SERM bound [19].

Helix 12 positioning is particularly crucial—agonists position H12 over the ligand-binding pocket, enabling coactivator recruitment, while SERMs and antagonists displace H12, blocking the activation function-2 (AF-2) surface and preventing coactivator binding [17] [19]. Different SERMs induce unique H12 positions, leading to varied receptor conformations that influence tissue-specific responses.

Tissue-Specific Factors Influencing STR

The tissue-selective action of SERMs arises from several key factors:

Differential expression of ER subtypes: Tissues vary in their expression of ERα versus ERβ, which have distinct physiological functions and respond differently to SERMs [18]. For example, ERα mediates proliferation in breast tissue, while ERβ may have anti-proliferative effects.

Tissue-specific coregulator expression: The relative abundance of coactivators (e.g., SRC-1, SRC-3) and corepressors (e.g., NCoR, SMRT) in different tissues determines whether a SERM acts as an agonist or antagonist [17] [18].

Ligand-specific receptor conformations: Each SERM induces a unique ER conformation that affects its ability to interact with tissue-specific coregulatory proteins [17] [19].

Epigenetic and post-translational modifications: Phosphorylation, acetylation, and other modifications of ER and coregulators further influence tissue-specific responses to SERMs [18].

Experimental Protocols for STR Assessment

Protocol 1: Quantitative Tissue Distribution Studies

Objective: To quantitatively determine the concentration of SERMs in target tissues (tumor, bone, uterus, fat pad) versus plasma and calculate tissue selectivity indices.

Materials:

- Test SERM compounds (≥95% purity)

- Animal model (e.g., ovariectomized mice with ER+ breast tumor xenografts)

- Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system

- Tissue homogenization equipment

- Stable isotope-labeled internal standards

Procedure:

- Dosing: Administer SERMs via appropriate route (oral preferred for clinical relevance) at therapeutically relevant doses.

- Sample Collection: At predetermined timepoints post-dose, collect blood (for plasma), tumor tissue, bone, uterus, and other relevant tissues.

- Sample Processing:

- Weigh each tissue sample accurately

- Homogenize tissues in appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline)

- Extract SERMs using protein precipitation or solid-phase extraction

- Quantitative Analysis:

- Analyze samples using validated LC-MS/MS methods

- Use calibration curves with internal standards for precise quantification

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate tissue-to-plasma ratios for each SERM

- Determine tissue selectivity indices (e.g., tumor-to-uterus ratio)

- Perform statistical comparisons between SERMs with minor structural modifications

Key Parameters:

- Time of peak tissue concentration (Tmax,tissue)

- Tissue exposure (AUC0-t,tissue)

- Tissue-to-plasma ratio

- Selectivity index between target and off-target tissues

Protocol 2: Structural Determinants of Tissue Exposure

Objective: To correlate specific structural features with tissue exposure patterns and identify STR principles.

Materials:

- Series of structurally related SERM analogs

- Molecular modeling software

- Protein binding assessment tools (e.g., equilibrium dialysis)

- Tumor tissue penetration assay components

Procedure:

- Structural Characterization:

- Document specific structural variations (side chain length, functional groups, stereochemistry)

- Calculate physicochemical properties (log P, polar surface area, hydrogen bonding capacity)

- Protein Binding Assessment:

- Determine plasma protein binding using equilibrium dialysis

- Correlate protein binding with tissue distribution patterns

- Molecular Modeling:

- Dock SERM structures into ER ligand-binding domain

- Identify key interactions with amino acid residues

- Correlate structural features with tissue exposure data

- STR Model Development:

- Build quantitative structure-tissue exposure relationship (QSTR) models

- Validate models with test set compounds

Key Insights: SERMs with high protein binding showed higher accumulation in tumors compared to surrounding normal tissues, likely due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect of protein-bound drugs [14] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for STR Studies of SERMs

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in STR Research |

|---|---|---|

| SERM Compounds | Tamoxifen, Raloxifene, Bazedoxifene, Lasofoxifene, Toremifene | Reference compounds for establishing baseline STR profiles and validating experimental systems |

| ER-Binding Assays | Fluorescence polarization assays, Time-resolved FRET assays, Competitive binding kits | Quantify binding affinity to ERα and ERβ subtypes and correlate with tissue distribution |

| Cellular Models | MCF-7 (breast cancer), T47D (breast cancer), Ishikawa (endometrial), Primary osteoblasts | Assess tissue-specific transcriptional responses and functional outcomes in relevant cellular contexts |

| Animal Models | Ovariectomized mice, ER+ breast cancer xenografts, Osteoporosis models | Evaluate in vivo tissue distribution and selectivity in physiologically relevant systems |

| Analytical Tools | LC-MS/MS systems, Stable isotope-labeled internal standards, Tissue homogenization equipment | Precisely quantify compound concentrations in complex biological matrices |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Coactivator/corepressor expression plasmids, ER subtype-specific antibodies, Reporter gene constructs | Elucidate mechanisms underlying tissue-specific responses to structurally distinct SERMs |

| Rimtuzalcap | Rimtuzalcap, CAS:2167246-24-2, MF:C18H24F2N6O, MW:378.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Rivipansel | Rivipansel | Rivipansel is a pan-selectin inhibitor for research into sickle cell disease (SCD) and vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

STR-Driven Experimental Workflow

This case study demonstrates that slight structural modifications in SERMs can dramatically alter their tissue exposure and selectivity profiles without significantly affecting plasma pharmacokinetics [14] [5]. The integration of STR assessment into standard drug optimization workflows provides a powerful approach to select clinical candidates with improved efficacy/toxicity balances.

Future directions in STR research include:

- Development of computational models to predict tissue exposure based on structural features

- Exploration of novel SERM scaffolds with improved tissue selectivity profiles

- Investigation of transport mechanisms governing tissue-specific SERM distribution

- Application of STR principles to other drug classes beyond hormone receptor modulators

The systematic evaluation of Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity relationships represents a paradigm shift in drug development, moving beyond traditional SAR to optimize tissue-level distribution for enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

From Theory to Lab: Methodological Approaches for STR Analysis

In contemporary drug discovery, the structure–tissue exposure/selectivity relationship (STR) has emerged as a critical complement to the traditional structure–activity relationship (SAR) for selecting viable drug candidates [6] [15]. While SAR focuses on improving drug potency and specificity through structural modification, STR addresses how these modifications alter a compound's distribution profile between target and non-target tissues—a factor directly correlated with clinical efficacy and safety [20] [21]. The pharmaceutical industry's high clinical failure rate (approximately 90%) is partly attributable to an overreliance on plasma pharmacokinetics while overlooking tissue-specific exposure [6] [15]. This application note details key assays, with emphasis on liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methodologies and complementary approaches, for comprehensive tissue exposure profiling within the integrated STR-SAR framework essential for informed lead optimization.

Table 1: Key STR Findings from Recent Studies

| Compound Class | Key STR Finding | Clinical Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBD Carbamates | L2 and L4 had similar plasma exposure but 5-fold difference in brain exposure | Direct correlation with efficacy/toxicity profile despite similar plasma PK | [6] [20] |

| Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) | Slight structural modifications significantly altered tissue selectivity without changing plasma exposure | Correlation with clinical efficacy/safety profiles in target tissues | [15] [21] |

| Covalent Inhibitors | Uncoupling of drug concentration and effect due to irreversible target binding | Necessitates specialized PK/PD models for accurate efficacy prediction | [22] |

Core LC-MS/MS Methodologies for Tissue Exposure Quantification

Fundamental LC-MS/MS Workflow and Instrumentation

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has become the cornerstone analytical technique for tissue exposure profiling due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and ability to detect a broad spectrum of analytes in complex biological matrices [23]. The fundamental workflow involves tissue homogenization, metabolite extraction, chromatographic separation, and mass spectrometric detection [24]. Modern advancements include ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) systems coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometers (HRMS) such as quadrupole-time of flight (Q-TOF), Orbitrap, and triple quadrupole (QQQ) instruments, which provide the rapid analysis times (2-5 minutes per sample) and precision required for high-throughput drug development pipelines [23].

Figure 1: Comprehensive LC-MS/MS Workflow for Tissue Exposure Profiling

Advanced LC-MS/MS Applications in Tissue Exposure Studies

Untargeted Metabolomics for Comprehensive Exposure Assessment

Untargeted metabolomics using LC-MS provides extensive coverage of metabolite detection, which is crucial for understanding both drug distribution and resulting metabolic perturbations. As demonstrated in zebrafish models, an integrated approach combining hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) maximizes metabolite detection breadth [24]. Key parameters requiring optimization include tissue homogenization techniques, extraction solvents, and redissolution solvents. This method enabled annotation of 620 metabolites and identification of 110 differential variables related to zebrafish growth, primarily associated with glycerophospholipid metabolism and amino acid biosynthesis pathways [24].

Targeted Quantification for Precise PK/PD Modeling

Targeted LC-MS/MS assays, particularly using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on triple quadrupole instruments, provide the sensitivity and specificity required for precise quantification of drug candidates in specific tissues. In studies of CBD carbamates, a validated UPLC-HRMS method demonstrated that compounds with similar plasma exposure (L2 and L4) showed markedly different brain distribution, directly impacting their efficacy and safety profiles [6] [20]. This approach enables calculation of critical STR parameters such as tissue-to-plasma distribution coefficients (Kp), which determine overall drug exposure in tissues according to the relationship: Drug exposure in tissue = Drug exposure in plasma × Kp [6].

Table 2: Quantitative Tissue Exposure Data for CBD Carbamates

| Compound | Plasma AUC | Brain AUC | Brain-to-Plasma Ratio (Kp) | BuChE ICâ‚…â‚€ | Acute Oral Toxicity (LDâ‚…â‚€) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBD (L0) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | 319.5 mg/kg |

| L1 | Low | Low | Moderate | Similar to CBD | 22.1 mg/kg |

| L2 | High | High | High | 0.077 μM | 70.5 mg/kg |

| L3 | Low | Low | Moderate | Similar to CBD | 80.0 mg/kg |

| L4 | High | Low | Low | Most potent | 84.0 mg/kg |

Complementary and Emerging Assay Technologies

Intact Protein MS for Covalent Drug-Target Engagement

For covalent drugs that form irreversible bonds with their targets, traditional LC-MS/MS approaches face limitations due to the uncoupling of free drug concentration and pharmacological effect [22]. Intact protein mass spectrometry addresses this challenge by directly quantifying target engagement (%TE) through measurement of the drug-protein complex. This method has been applied successfully to targets including KRAS, BTK, and SOD1, with a typical workflow involving protein extraction from tissues (e.g., via chloroform/ethanol partitioning), LC separation of intact protein, and high-resolution mass detection [22].

Figure 2: Intact Protein MS Workflow for Covalent Drug Tissue Exposure

LC-MS-Based Proteomics for Mechanistic Insights

LC-MS-based proteomics provides complementary value to tissue exposure studies by mapping protein-level alterations in response to drug treatment, thereby elucidating mechanisms of efficacy and toxicity [25]. Both label-free and label-based quantification methods can identify dysregulated pathways and potential biomarkers in tissues following drug exposure. For example, this approach has revealed how natural products like berberine directly bind to PKM2 to modulate colorectal cancer pathways, and how Withaferin A regulates proteins in prostate cancer models [25]. The technology encompasses various workflows including bottom-up proteomics, top-down proteomics, and data-independent acquisition (DIA), with selection dependent on specific research questions regarding tissue responses to drug exposure.

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive Tissue Exposure Assessment

Protocol: Tissue Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction for Untargeted LC-MS

This protocol optimizes tissue preparation for comprehensive metabolite extraction, adapted from zebrafish whole-tissue metabolomics methodology [24].

Reagents and Materials:

- Pre-chilled methanol (MeOH) and acetonitrile (ACN) (HPLC grade)

- Water (HPLC grade)

- Ceramic or glass homogenizers

- Cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Dry ice or liquid nitrogen

- Microcentrifuge tubes

Procedure:

- Tissue Homogenization: Rapidly harvest tissue and immediately freeze in liquid nitrogen. Weigh approximately 50 mg of tissue and add to 500 μL of pre-chilled MeOH:ACN (1:1 v/v) in a homogenizer. Homogenize on ice until fully dispersed.

- Metabolite Extraction: Transfer homogenate to a microcentrifuge tube. Add 500 μL of pre-chilled ACN, vortex vigorously for 60 seconds, and incubate at -20°C for 60 minutes.

- Protein Precipitation: Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Carefully collect supernatant and transfer to a new tube.

- Sample Concentration: Evaporate solvent under a gentle nitrogen stream at room temperature.

- Sample Reconstitution: Reconstitute dried extract in 100 μL of ACN:water (1:1 v/v) appropriate for either RPLC or HILIC analysis. Vortex for 30 seconds and centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes before LC-MS analysis.

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain samples at 4°C or below throughout extraction when possible

- Use antioxidant additives (e.g., ascorbic acid) for oxidation-sensitive metabolites

- Process quality control (QC) samples by pooling aliquots from all samples

Protocol: Intact Protein MS for Target Engagement Quantification

This protocol details the measurement of target engagement for covalent drugs in tissue samples, based on published methodologies for SOD1-targeting compounds [22].

Reagents and Materials:

- Chloroform and ethanol (HPLC grade)

- Protein precipitation plates or tubes

- Immunoprecipitation reagents (antibody against target protein)

- Intact protein LC-MS column (e.g., C4 or C8 for large proteins)

- Formic acid (MS grade)

Procedure:

- Protein Extraction from Tissue: Homogenize approximately 20 mg tissue in 200 μL of ice-cold PBS. Add 400 μL of chloroform:ethanol (2:1 v/v) solution, vortex for 60 seconds, and incubate on ice for 15 minutes.

- Partitioning: Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Collect the interphase layer containing proteins.

- Protein Purification: Wash protein pellet with cold ethanol and centrifuge again. Resuspend in appropriate LC-MS compatible buffer.

- LC-MS Analysis: Inject onto LC-MS system with C4 or C8 column. Use gradient elution with water-ACN containing 0.1% formic acid. MS detection in full scan mode with appropriate mass range for target protein and drug-protein complex.

- Data Analysis: Deconvolute mass spectra to determine relative abundances of unmodified and drug-bound protein. Calculate %TE using the formula: %TE = (Intensity of drug-protein complex / Total protein intensity) × 100.

Critical Parameters:

- Optimize extraction protocol for specific protein target

- Include controls from untreated animals

- Use high-resolution MS for accurate mass determination of large proteins

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Tissue Exposure Assays

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Tissue Exposure Profiling | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | HILIC, RPLC (C18, C8), Intact Protein (C4) | Separation of analytes from complex tissue matrices | HILIC for polar metabolites; RPLC for non-polar compounds; C4 for intact proteins |

| Ionization Sources | Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) | Generation of gas-phase ions for mass analysis | ESI for polar and larger molecules; APCI for less polar compounds |

| Mass Analyzers | Q-TOF, Orbitrap, Triple Quadrupole (QQQ) | Mass separation and detection | Q-TOF/Orbitrap for untargeted; QQQ for targeted quantification |

| Internal Standards | Stable isotope-labeled analogs of analytes | Correction for matrix effects and extraction efficiency | Essential for accurate quantification in complex tissues |

| Protein Extraction Kits | Chloroform/ethanol-based precipitation, Immunoprecipitation kits | Isolation of target proteins from tissue homogenates | Critical for intact protein MS and target engagement studies |

| Quality Controls | Pooled tissue QC samples, process blanks | Monitoring analytical performance and data quality | Identify technical variations and maintain platform stability |

| Rovatirelin | Rovatirelin | Rovatirelin is a novel thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) analog for research on spinocerebellar degeneration and ataxia. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| RQ-00203078 | RQ-00203078 is a highly selective, orally active TRPM8 antagonist (IC50=8.3 nM). For research use only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Comprehensive tissue exposure profiling through LC-MS/MS and complementary technologies provides indispensable data for understanding the structure-tissue exposure/selectivity relationship (STR) in drug development [6] [15] [20]. The case studies presented demonstrate that drug exposure in plasma frequently fails to predict exposure in target tissues, and that tissue exposure/selectivity shows stronger correlation with clinical efficacy and safety outcomes [6] [21]. By integrating STR assessment with traditional SAR during lead optimization, drug developers can make more informed candidate selection decisions, potentially improving the success rate of clinical drug development through better balancing of efficacy and toxicity profiles [15] [20]. The protocols and methodologies detailed in this application note provide a framework for implementing robust tissue exposure profiling in preclinical drug development workflows.

Leveraging ADMET Parameters to Predict Tissue Selectivity

The Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) is an emerging critical concept in drug optimization that complements the traditional Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR). While SAR focuses on improving a compound's potency and specificity against its molecular target, STR emphasizes the crucial link between a drug's chemical structure, its resulting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties, and its ultimate exposure and selectivity in target tissues versus off-target tissues [5] [6]. Overemphasis on plasma exposure and insufficient attention to tissue-level distribution is a significant contributor to the high failure rate (∼90%) in clinical drug development, often due to a lack of efficacy (40-50%) or unmanageable toxicity (30%) [26] [6]. This application note details how the strategic application of in silico and in vitro ADMET parameters can be leveraged to predict tissue selectivity early in the drug discovery process, thereby de-risking candidate selection and improving the probability of clinical success.

The STR Framework: Integrating ADMET for Tissue-Level Prediction

The core premise of STR is that drug exposure in plasma is not always correlated with exposure in disease-targeted tissues [5] [6]. Consequently, a drug candidate with favorable plasma pharmacokinetics may still fail if it does not adequately reach the target site or if it accumulates in sensitive normal tissues, leading to toxicity.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for applying ADMET predictions to assess tissue selectivity within the STR framework.

Key Principle: Drug exposure in a specific tissue is a function of its plasma exposure and the tissue-to-plasma distribution coefficient (Kp), as defined by the equation: Drug exposure in tissue = Drug exposure in plasma × Kp [6]. ADMET parameters are instrumental in predicting both components of this equation.

Key ADMET Parameters for Predicting Tissue Selectivity

The following parameters, often predicted using machine learning (ML) models or measured in vitro, provide critical insights into a compound's likely tissue distribution profile [27] [28].

Table 1: Key ADMET Parameters for Tissue Selectivity Assessment

| ADMET Parameter | Description | Utility in Predicting Tissue Selectivity | Common Predictive Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Permeability (e.g., Caco-2, PAMPA) | Measures passive diffusion across membranes. | Predicts ability to cross tissue barriers (e.g., intestinal wall, blood-brain barrier). | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Support Vector Machines (SVM) [27] [28] |

| Transporter Affinity (e.g., P-gp, BCRP) | Identifies substrates of efflux transporters. | Flags compounds likely to be excluded from specific tissues (e.g., brain) or accumulated in eliminating organs. | Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks [28] |

| Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) | Quantifies the fraction of drug bound to plasma proteins. | Influences the volume of distribution and free drug available for tissue partitioning. High PPB can enhance tumor accumulation via the EPR effect [5]. | Multitask Learning Models, AdmetSAR [26] [28] |

| Tissue-to-Plasma Partition Coefficient (Kp) | Predicts equilibrium concentration ratio between tissue and plasma. | Directly quantifies a compound's tendency to distribute into and accumulate in specific tissues. | Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, ensemble ML methods [6] [28] |

| Metabolic Stability (e.g., in liver microsomes) | Measures the rate of compound metabolism. | Impacts overall systemic exposure (AUC) and, consequently, tissue exposure levels. | Deep Learning (e.g., CNNs, RNNs) on structural data [29] [30] [28] |

| hERG Inhibition | Predicts potential for cardiac channel blockage. | Serves as a proxy for cardiac tissue exposure and associated toxicity risk. | ADMET-AI, admetSAR, TEST [31] [26] |

Experimental Protocols for STR-Driven ADMET Profiling

Protocol: IntegratedIn SilicoADMET Screening for Tissue Selectivity

This protocol utilizes a consensus-based cheminformatics approach to generate an initial STR hypothesis [26].

Input Structure Preparation:

- Generate and optimize 3D structures of candidate compounds.

- Convert structures into SMILES notation or appropriate molecular descriptor formats.

Multi-Platform In Silico Profiling:

- Utilize a panel of at least 3-5 distinct software/platforms (e.g., SwissADME, admetSAR, AdmetLab, pkSCM) to predict the parameters listed in Table 1 [26].

- Rationale: Using multiple platforms mitigates individual tool bias and provides a more robust consensus.

Data Consolidation and Analysis:

- Compile results into a unified database.

- Apply a scoring system to classify compounds as high, medium, or low risk for each parameter. For instance, a compound predicted as a strong P-gp substrate by >60% of platforms would be flagged as high risk for poor brain penetration.

STR Hypothesis Generation:

- Integrate the ADMET scores to formulate a tissue selectivity profile. For example, a compound with high passive permeability, low P-gp substrate probability, and high predicted Kp_brain is a strong candidate for central nervous system (CNS) targets.

Protocol:In VitroValidation of Tissue Distribution

This protocol outlines the key experimental steps to validate in silico predictions, using a preclinical model as an example [32].

Animal Dosing and Sample Collection:

- Model: Use a relevant disease model (e.g., patient-derived orthotopic xenograft model).

- Dosing: Administer the candidate drug(s) via the intended clinical route (e.g., oral gavage).

- Sacrifice and Collection: Euthanize animals at predetermined time points. Collect blood (for plasma), target tissue (e.g., tumor, brain), and potential toxicity-related tissues (e.g., liver, heart).

Bioanalytical Quantification:

Data Calculation and STR Assessment:

- Calculate key pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC) for plasma and each tissue.

- Determine the tissue-to-plasma distribution coefficient (Kp) using the formula: Kp = AUCtissue / AUCplasma.

- Calculate the Tissue Selectivity Index (TSI) for efficacy versus toxicity: TSI = Kptargettissue / Kptoxictissue. A higher TSI indicates a more favorable STR profile.

The following diagram summarizes this key experimental and analytical workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for ADMET and STR Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use in STR Context |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Model of human intestinal permeability. | Predicts oral absorption and potential for systemic exposure [28]. |

| MDCK or MDCK-MDR1 Cells | Canine kidney cells; latter transfected with human P-gp. | Assesses permeability and identifies P-gp efflux transporter substrates, predicting brain penetration [26]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes | Contains major human cytochrome P450 enzymes. | Evaluates metabolic stability, informing systemic and tissue half-life [29]. |

| T.E.S.T. (Toxicity Estimation Software) | EPA-developed software for toxicity prediction. | Provides early warnings for tissue-specific toxicities (e.g., mutagenicity, hepatotoxicity) [26]. |

| ADMET-AI / admetSAR | Machine learning platforms for ADMET prediction. | High-throughput in silico screening of key parameters like PPB, hERG, and solubility [31] [26]. |

| UPLC-HRMS / LC-MS/MS | High-sensitivity bioanalytical instrumentation. | Quantifies drug concentrations in complex matrices like tissue homogenates for Kp calculation [6] [32]. |

| Zalunfiban | Zalunfiban (RUC-4) | Zalunfiban is a novel subcutaneously administered GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor for STEMI research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| Runcaciguat | Runcaciguat|sGC Activator for CKD Research | Runcaciguat is a novel, orally active sGC activator for chronic kidney disease (CKD) research. It restores cGMP signaling under oxidative stress. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Integrating ADMET parameter analysis to predict tissue selectivity is no longer an optional refinement but a necessary component of modern, efficient drug optimization. By adopting the STR framework and employing the described protocols and tools—from consensus in silico screening to targeted in vivo validation—researchers can make more informed decisions during lead optimization. This paradigm shift from a primary focus on plasma exposure to a comprehensive understanding of tissue-level exposure and selectivity holds significant promise for improving the clinical success rate of drug candidates by achieving a better balance between efficacy and safety.

The Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) represents a critical paradigm in modern drug development, emphasizing that a drug's distribution profile across different tissues is a deterministic factor for its clinical efficacy and safety [5]. Traditional drug optimization has heavily focused on the Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR) to enhance potency and specificity. However, an overemphasis on SAR often overlooks a crucial reality: drugs with similar plasma exposure can have vastly different distributions in target versus non-target tissues, leading to unexpected clinical outcomes [6] [5] [20]. Integrating STR analysis ensures that drug candidate selection balances both pharmacological activity and tissue-specific exposure, thereby improving the probability of success in clinical trials.