Beyond Maximum Tolerated Dose: A Mathematical Modeling Approach to Optimizing Combination Therapy in Oncology

The paradigm for dosing oncology drugs is shifting from the traditional maximum tolerated dose (MTD) approach toward model-informed, optimized strategies, particularly for modern targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

Beyond Maximum Tolerated Dose: A Mathematical Modeling Approach to Optimizing Combination Therapy in Oncology

Abstract

The paradigm for dosing oncology drugs is shifting from the traditional maximum tolerated dose (MTD) approach toward model-informed, optimized strategies, particularly for modern targeted therapies and immunotherapies. This article explores the transformative role of mathematical modeling in optimizing combination therapy doses, a critical challenge in cancer treatment. We cover the foundational principles of mathematical oncology, detail key methodological approaches like Quantitative Systems Pharmacology and exposure-response modeling, and examine their application in clinical trial design. The article also addresses troubleshooting for common hurdles like stromal-induced resistance and outlines validation frameworks through recent clinical trials and regulatory initiatives like Project Optimus. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how computational models are paving the way for more effective, personalized, and less toxic combination cancer therapies.

The New Paradigm: Why Mathematical Models are Replacing Maximum Tolerated Dose

The Limitation of the MTD Paradigm for Modern Therapies

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Moving Beyond MTD

Problem 1: High rates of dose reduction in late-stage trials.

- Root Cause: Reliance on the traditional 3+3 dose-escalation design, which focuses on short-term dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) and fails to represent the long treatment courses of modern therapies [1].

- Solution: Implement novel trial designs like model-informed dose escalation and randomized dose-selection sub-studies to better characterize the dose-response relationship and long-term tolerability [2] [1].

Problem 2: Rapid emergence of drug resistance and treatment failure.

- Root Cause: The MTD approach applies intense evolutionary pressure, eliminating drug-sensitive cells and causing "competitive release" of resistant populations [3] [4].

- Solution: Utilize adaptive therapy strategies, informed by mathematical models (e.g., Lotka-Volterra systems), to maintain sensitive cells and suppress resistant growth [3] [5].

Problem 3: Inefficient dose optimization delaying drug development.

- Root Cause: Attempting to optimize dosage only in post-approval settings, which can take years [6].

- Solution: Integrate dose optimization early in preclinical development using quantitative systems pharmacology models and exposure-response analyses [2] [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the traditional Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) paradigm no longer suitable for many modern cancer drugs? The MTD paradigm, developed for cytotoxic chemotherapies, is based on determining the highest dose patients can tolerate in a short first course of treatment [2]. This approach is suboptimal for targeted therapies and immunotherapies because their mechanism of action differs; efficacy often saturates at a certain level, and higher doses only increase toxicity without improving efficacy [5]. Studies show that nearly 50% of patients on targeted therapies require dose reductions, and the FDA has mandated post-approval dose re-evaluation for over 50% of recently approved cancer drugs [1].

FAQ 2: What is the alternative to the MTD approach? The leading alternative is dose optimization, which aims to identify the Optimal Biological Dose (OBD) that best balances efficacy and tolerability [2]. This involves:

- Using randomized trials to compare multiple doses before approval [6].

- Employing model-informed drug development (MIDD) and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling [1].

- Shifting towards adaptive therapy strategies that control tumor growth rather than seeking maximal cell kill [3] [4].

FAQ 3: How can mathematical modeling improve dose selection for combination therapies? Mathematical models, such as Lotka-Volterra competition models, help simulate complex eco-evolutionary dynamics within tumors during treatment [3] [5]. For combination therapy, they can:

- Predict the emergence of resistance to multiple drugs.

- Identify synergistic dosing schedules that exploit fitness costs to resistant subpopulations.

- Optimize "first-strike, second-strike" sequential therapy strategies to delay or prevent resistance [5] [4].

FAQ 4: What trial designs are recommended for dose optimization? Regulatory guidance now encourages randomized dose-finding trials before approval [2]. Recommended designs include:

- Model-informed designs: Utilize mathematical modeling for more nuanced dose-escalation/de-escalation based on efficacy and late-onset toxicities [1].

- Adaptive seamless designs: Combine traditionally separate trial phases (e.g., FIH and proof-of-concept) to accelerate enrollment and gather more long-term data [1].

- Backfill and expansion cohorts: Increase patient numbers at specific dose levels within early-stage trials to strengthen understanding of the benefit/risk ratio [1].

FAQ 5: What data should be collected to inform the Optimal Biological Dose (OBD)? Dose selection should be justified by a totality of evidence, moving beyond just early-cycle toxicities [2]. Key data includes:

- Longitudinal patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and quality-of-life metrics [2].

- Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) and exposure-response relationships [1].

- Biomarker data (e.g., ctDNA dynamics) to identify early response signals [1].

- Cumulative and delayed toxicities occurring after cycle 1 [2].

Quantitative Data on MTD Limitations and New Paradigms

Table 1: Documented Limitations of the MTD Paradigm

| Metric | Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Dose Reductions | Nearly 50% of patients on late-stage trials of small molecule targeted therapies required dose reductions due to side effects. | [1] |

| FDA Post-Approval Actions | Over 50% of recently approved cancer drugs required additional studies to re-evaluate dosing. | [1] |

| Patient-Reported Toxicity | 86% of patients with metastatic breast cancer reported significant treatment-related side effects. | [6] |

| Clinician Support for Change | Over 80% of surveyed oncologists strongly supported future trials focused on optimal dose determination over MTD. | [6] |

Table 2: Key Mathematical Models for Therapy Optimization

| Model Type | Primary Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Lotka-Volterra Competition Models | Adaptive Therapy | Models competition between drug-sensitive and resistant cell populations to design therapy schedules that suppress resistance [3]. |

| Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Models | Dose-Response Characterization | Links drug exposure (pharmacokinetics) to biological effect (pharmacodynamics) to predict efficacy and toxicity [1] [5]. |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Final Dosage Decision | Integrates larger clinical datasets to identify optimized dosages, extrapolate effects of untested schedules, and address confounders [1]. |

| Bang-Bang Control Theory | Intermittent vs. Continuous Dosing | Formally analyzes intermittent adaptive therapy and proves robustness of continuous adaptive therapy [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Dose Optimization Research

Protocol 1: Implementing a Model-Informed First-in-Human (FIH) Trial

Objective: To identify a range of safe and potentially effective doses for further study, moving beyond the algorithmic 3+3 design [1].

Methodology:

- Starting Dose Selection: Use mathematical models that go beyond animal weight-based scaling. Incorporate factors like receptor occupancy differences between species to determine a higher, potentially more efficacious, starting dose [1].

- Dose Escalation: Employ model-informed dose escalation designs (e.g., continual reassessment method). These designs use statistical models to continuously update the probability of toxicity and efficacy based on all accumulated data from previous patients, allowing for more efficient and nuanced dose escalation/de-escalation decisions [1].

- Data Collection: Collect pharmacokinetic (PK) samples, early pharmacodynamic (PD) biomarkers (e.g., ctDNA), and monitor for both early and late-onset toxicities [1].

Protocol 2: Randomized Dose-Selection (Proof-of-Concept) Study

Objective: To directly compare multiple doses and identify the leading candidate for registrational trials [2] [1].

Methodology:

- Dose Selection: Choose 2-3 doses from the FIH trial that span a range of biological activity and safety profiles.

- Trial Design: Randomize patients to the different dose arms. Incorporate backfill or expansion cohorts to enroll more patients at doses of particular interest [1].

- Endpoint Assessment: Assess antitumor activity (e.g., objective response rate), safety, tolerability, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Integrate biomarker data (e.g., ctDNA) for early response detection [1].

- Decision Framework: Use a quantitative framework like a Clinical Utility Index (CUI) to integrate all available efficacy, safety, and PK/PD data and justify the final dose selection [1].

Protocol 3: Calibrating a Mathematical Model for Adaptive Therapy

Objective: To develop a patient-specific model for predicting response to adaptive dosing schedules [3] [5].

Methodology:

- Model Selection: Use a two-population Lotka-Volterra system to represent sensitive (x) and resistant (y) cell dynamics:

dx/dt = r_x * x * (1 - x - α * y) - K_A(x,y,t) * h(x, r_d)dy/dt = r_y * y * (1 - y - β * x)whereris growth rate,αandβare competition coefficients, andK_Ais the treatment function [3]. - Parameter Estimation: Calibrate model parameters (rx, ry, α, β) using longitudinal tumor burden data (e.g., from imaging or PSA levels) from historical cohorts or the patient's initial treatment cycles [5].

- Schedule Simulation: Simulate different therapy schedules (continuous fixed-dose, intermittent on-off, continuous adaptive) to predict which strategy maximizes time to progression for that specific patient [3].

- Validation: Compare model predictions to actual patient outcomes in pilot clinical trials (e.g., NCT03543969 for melanoma, NCT02415621 for prostate cancer) [5].

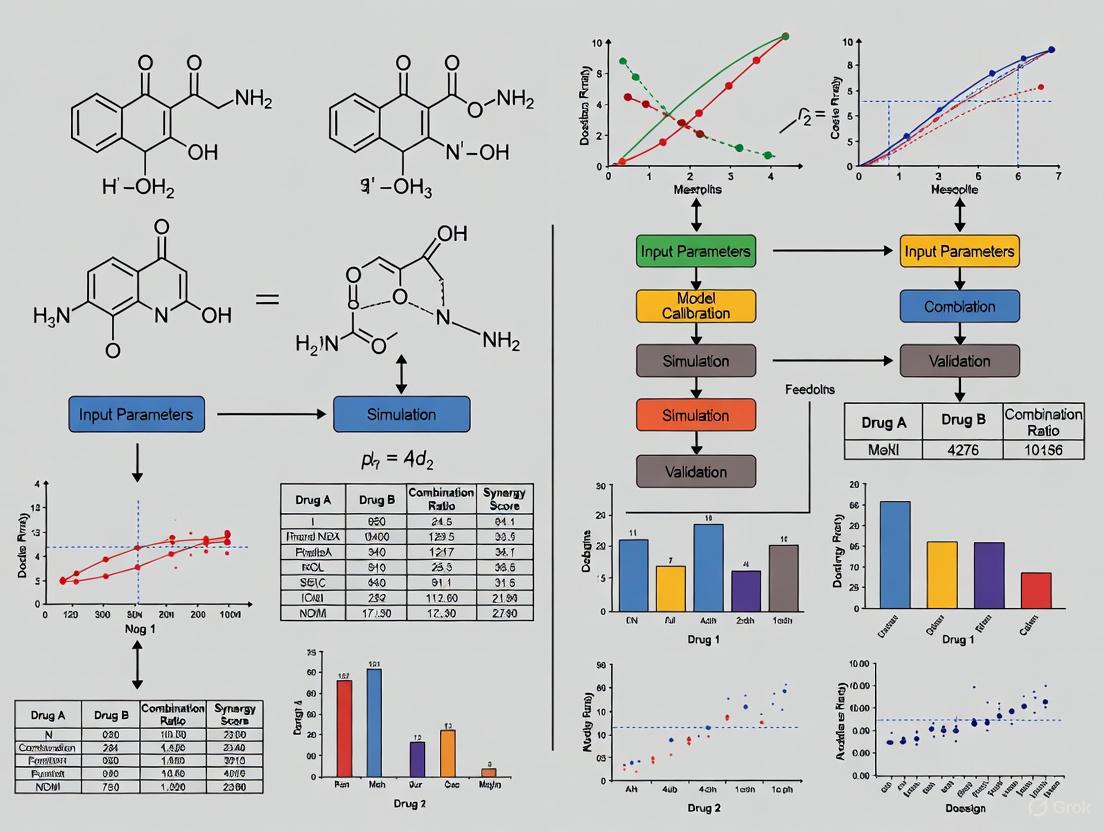

Diagram: Workflow for Model-Informed Dose Optimization

Model-Informed Dose Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Dose Optimization Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | A liquid biopsy biomarker used to track tumor burden and response dynamics early in treatment, informing dose-response relationships [1]. |

| Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Measures | Standardized questionnaires to capture the patient's perspective on treatment side effects and quality of life, critical for evaluating the tolerability of different doses [2]. |

| Lotka-Volterra Competition Model | A system of differential equations used to model the competitive interaction between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cell populations under treatment pressure [3]. |

| Clinical Utility Index (CUI) | A quantitative framework that integrates multiple endpoints (efficacy, toxicity, PROs) into a single score to aid in collaborative and objective dose selection [1]. |

| Population PK/PD Models | Mathematical models that quantify the relationship between drug dose, systemic exposure (pharmacokinetics), and biological effect (pharmacodynamics) across a patient population [1]. |

| S1P1 Agonist III | S1P1 Agonist III, MF:C21H16F3N3O3, MW:415.4 g/mol |

| TCH-165 | TCH-165, MF:C39H37N3O3, MW:595.7 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary clinical challenge when combining multiple anti-cancer drugs, and how can mathematical oncology help? A key challenge is determining safe and effective starting doses for novel drug combinations, especially those involving both targeted and cytotoxic agents. Mathematical modeling analyzes historical clinical trial data to establish that for three-drug combinations, less than 30% of studies could administer all three drugs at their full single-agent dose. Dose reductions to as low as 45% of each single agent's dose are often required. Modeling provides a quantitative framework to predict safe additive dose percentages, helping to avoid excessive toxicity in early-phase trials [7].

Q2: My mathematical model fits the training data well but fails to predict unseen test data. What should I do? This is a common step in the modeling workflow. A model that fails to predict unseen data is not necessarily "wrong"; it often indicates that the model lacks a biological process that becomes important under the new conditions (e.g., in vivo versus in vitro). Use this failure to refine your model. For instance, if the model accurately predicts the first 8 days of tumor spheroid growth but fails thereafter, consider if processes like drug resistance, immune responses, or angiogenesis—not accounted for in the original model—begin to dominate at that point. This failure provides a critical opportunity to challenge the model's assumptions and integrate new biology [8].

Q3: How can optimal control theory be applied to combination therapy? Optimal control theory can determine dosage protocols that steer a patient's state from a malignant condition (tumor escape) to a benign one (equilibrium). This involves formulating a mathematical model of tumor-immune-drug interactions and then solving for the time-varying dose rates (controls) that minimize an objective function, which typically balances tumor burden and drug toxicity. The solution suggests how to schedule chemo- and immunotherapy over time to leverage their synergistic effects, such as the immune-stimulatory release of tumor antigens following chemotherapy [9].

Q4: What are the "Three E's of Immuno-editing" in mathematical models? This qualitative framework describes the possible long-term outcomes of tumor-immune interactions modeled by dynamical systems [9]:

- Elimination: The immune system eradicates the tumor. The tumor-free stationary point is stable.

- Equilibrium: The immune system controls the tumor, maintaining it in a dormant state. This is represented by a stable stationary point with a low, positive tumor volume.

- Escape: The tumor grows uncontrollably as it evades the immune response. This corresponds to an unstable stationary point with a high tumor volume. The goal of therapy is to revert an "escape" scenario back to "equilibrium."

Q5: What is the advantage of a dual-target inhibitor over combination therapy? While combining a cytotoxic drug with an epigenetic-targeted drug can overcome the limitations of single-agent therapy, it carries risks of drug-drug interactions, complex pharmacokinetics, and combined toxicity. Dual-target inhibitors are single molecules designed to simultaneously inhibit both an epigenetic and a cytotoxic pathway. This approach can simplify treatment, improve pharmacokinetic profiles, and more effectively overcome compensatory resistance mechanisms that limit single-target drugs [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Determining Safe Starting Doses for Novel Drug Combinations

Issue: Designing a first-in-human clinical trial for a new three-drug regimen involving targeted and cytotoxic therapies. The safe starting dose for the combination is unknown, and you wish to avoid excessive toxicity.

Solution: Utilize a model-derived "additive dose percentage" based on historical clinical trial data.

- Background: A systematic review of phase I-III trials provides a benchmark. The "dose percentage" for a drug is defined as (safe dose in combination / single-agent recommended dose) × 100. The "additive dose percentage" is the sum of this value for all three drugs in the combination [7].

- Methodology:

- Identify Combination Type: Classify your planned regimen.

- Consult Reference Data: Use the following table of historical safe additive dose percentages to guide your initial dose selection [7]:

| Combination Type | Number of Studies / Subjects | Median Additive Dose Percentage | Lowest Safe Additive Dose Percentage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Targeted Agent + 2 Cytotoxic Agents | 340 studies / 34,835 subjects | 267% | 137% | Only 28% of studies could give all 3 drugs at 100% dose [7]. |

| 2 Cytotoxic Agents at 100% Dose | 190 studies / 22,454 subjects | 300% | 225% | Applies when the cytotoxic doublet has a known safety profile. Not for HDAC inhibitors [7]. |

| 2 Targeted Agents + 1 Cytotoxic Agent | Information Missing | Information Missing | 133% | Increases to 250% if the two targeted agents are antibodies [7]. |

- Actionable Protocol:

- Calculate the theoretical maximum additive dose percentage (300% if all three drugs can be given at full dose).

- Based on your combination type, select a conservative starting additive dose percentage from the "Lowest Safe" column (e.g., 140-160% for a one-targeted, two-cytotoxic regimen).

- Allocate this total percentage across the three drugs, considering their individual toxicity profiles. For example, you might start with 50% of the targeted agent, 50% of cytotoxic drug A, and 40% of cytotoxic drug B (sum = 140%).

- Use this calculated dose for your initial cohort and proceed with standard phase I dose escalation.

Problem: Designing a Dose-Finding Trial Using Mathematical Modeling

Issue: You need to find the optimal vaccine or drug dose that maximizes efficacy while minimizing toxicity, but testing a large number of doses is impractical.

Solution: Implement a modeling-based dose-optimization approach within your trial design.

- Background: Instead of directly comparing a few doses, this method uses data from all trial participants to fit statistical models that describe the underlying dose-efficacy and dose-toxicity relationships [11].

- Methodology & Protocol:

- Choose Efficacy/Toxicity Models:

- For efficacy, use a binary outcome (e.g., immune response above a threshold). The dose-response can be "saturating" (monotonically increasing) or "peaking" (efficacy decreases after an optimum). Use models like the Latent Quadratic for peaking responses [11]:

Peaking(Dose) = 1 / [1 + e^(base + gradient1 * Dose + gradient2 * Dose^2)] - For toxicity, use an ordinal model (e.g., Grades 0-3) to capture lower-grade events that impact patient quality of life and uptake [11].

- For efficacy, use a binary outcome (e.g., immune response above a threshold). The dose-response can be "saturating" (monotonically increasing) or "peaking" (efficacy decreases after an optimum). Use models like the Latent Quadratic for peaking responses [11]:

- Define Utility Function: Combine the efficacy and toxicity models into a single "utility" function that balances the two, aiming to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity [11].

- Select Trial Design:

- Fixed-Dose Design: Pre-select doses across the expected range (e.g., low, medium, high).

- Adaptive Design (Recommended): Use continual modeling at interim stages. After each cohort, fit the models to all accumulated data and recommend the dose predicted to have the highest utility for the next cohort. This is more ethical and efficient [11].

- Determine Trial Size: Simulation studies suggest that modeling approaches perform well with at least 30 participants [11].

- Choose Efficacy/Toxicity Models:

Problem: Model Predicts Poor Synergy Between Chemo- and Immunotherapy

Issue: Your model of combination therapy fails to show the synergistic effects observed in some clinical contexts.

Solution: Ensure your model incorporates the immuno-stimulatory effects of cytotoxic drugs.

- Background: Chemotherapy can cause immunogenic cell death, releasing tumor antigens that stimulate an immune response. This is the basis for synergy with immunotherapy [9].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Audit Your Model Equations: Check if your model includes a variable for tumor antigen and a term linking its presence to immune cell stimulation.

- Include Key Dynamics: A minimal model should include [9]:

- Tumor Antigen (z):

ż = σx + ψxu - μzσx: Natural antigen production by tumor volume (x).ψxu: Therapy-induced antigen release (a function of tumor volume and drug dose u).μz: Clearance of antigen.

- Immuno-competent Cell Density (y):

Ạ= a(1 - bx)yz + γ - δy - κyu + νyva(1 - bx)yz: Proliferation stimulated by antigen (z).νyv: Boost from immunotherapy (v).

- Tumor Antigen (z):

- Calibrate Parameters: The parameter

ψ(therapy-induced immunogenicity) is critical. If it is set to zero, the synergistic effect will be lost. Consult literature for estimates or calibrate it against data showing the abscopal effect or similar phenomena.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

| Item / Concept | Function in Mathematical Oncology Research |

|---|---|

| Qualitative Dynamical Systems | Low-dimensional models (ODEs) to understand the totality of possible tumor-immune interactions, such as the "Three E's" of immunoediting. Useful for theoretical insights and optimal control studies [9]. |

| Cell-Based/Agent-Based Models | Computational models that simulate individual cells (agents) in a virtual tissue. Used to explore how single-cell behaviors (e.g., proliferation, death, mutation) lead to emergent tumor-scale dynamics like heterogeneity and drug resistance [12]. |

| Optimal Control Theory | A mathematical framework to compute time-varying dosage protocols (controls) that minimize a cost function (e.g., tumor burden + drug toxicity) subject to the constraints of a dynamical model of cancer treatment [9]. |

| Additive Dose Percentage Metric | A quantitative metric derived from historical clinical trial data to calculate safe starting doses for multi-drug combinations by summing the percentage of each drug's single-agent dose used in the combo [7]. |

| Dose-Utility Function | A function that combines a dose-efficacy model and a dose-toxicity model into a single value. It is maximized to identify the optimal dose that best balances treatment benefit and side effects [11]. |

| Model Averaging | A technique used when the true shape of the dose-response curve is unknown. Predictions from multiple models (e.g., saturating and peaking) are combined, weighted by how well each model fits the data, to make more robust inferences [11]. |

| TCO-amine | TCO-amine, CAS:1609736-43-7, MF:C12H22N2O2, MW:226.32 |

| TCO-C3-PEG3-C3-amine | TCO-C3-PEG3-C3-amine, MF:C19H36N2O5, MW:372.5 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow & Signaling Pathways

Diagram: Optimizing Combination Therapy Doses

Diagram: Three E's of Immuno-Editing & Therapy Goal

Optimizing Combination Therapy Doses Using Mathematical Modeling Research

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Dose-Response Model Fitting

Problem: Your dose-response model fails to adequately fit the experimental data, leading to unreliable estimates of potency (e.g., ECâ‚…â‚€) or efficacy (Eₘâ‚â‚“).

Solutions:

- Verify Data Quality: Ensure your experimental design includes an adequate number of data points, especially around the anticipated ECâ‚…â‚€. Confirm that the response measurements are precise and that controls are functioning correctly.

- Re-evaluate Model Selection: The Hill equation is a standard model for sigmoidal dose-response curves [13]. However, if your data does not reach a clear plateau, or if there is a baseline effect, the Emax model, which includes a parameter for the effect at zero dose (Eâ‚€), may be more appropriate [13].

- Check for Non-Monotonicity: In some biological systems, particularly with endocrine disruptors or immune responses, the dose-response relationship may be U-shaped or otherwise non-monotonic [13] [14]. Standard models will not fit this data well. Explore alternative models that can capture this complexity.

- Utilize Appropriate Software: Employ specialized software for dose-response modeling, such as the U.S. EPA's Benchmark Dose Software (BMDS), which provides robust statistical analysis and model averaging techniques [13] [15].

Guide 2: Accounting for Tumor Heterogeneity in Therapy Response

Problem: A combination therapy shows promising results in vitro but fails in vivo or yields highly variable patient responses due to pre-existing or acquired tumor heterogeneity.

Solutions:

- Implement Multiregion Sampling: Do not rely on a single tumor biopsy. Use multiregion sequencing to decode the complex clonal architecture and spatial heterogeneity of the tumor [16].

- Longitudinal Monitoring via Liquid Biopsies: Serial characterization of genetic variants in plasma samples (liquid biopsies) provides a minimally invasive method to track temporal heterogeneity and the emergence of resistant subclones during treatment [16].

- Adopt Combinatorial Strategies: Design therapies that pair agents targeting the dominant, drug-sensitive cell population with agents that target known or predicted resistant subclones. This "vertical" targeting is essential for durable responses [16].

- Incorporate Heterogeneity into Models: When building pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models, account for the differential sensitivity of distinct tumor subpopulations. This may involve modeling multiple cell types with different response parameters.

Guide 3: Managing Unexpected Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics in Preclinical Models

Problem: During long-term preclinical studies, the system under investigation (e.g., a xenograft model or a microbial infection) evolves, altering the therapy's effectiveness over time.

Solutions:

- Shorten Experiment Duration: If feasible, design studies to be completed within a timeframe that minimizes the opportunity for significant evolutionary change in the target system.

- Model Eco-Evolutionary Feedbacks: Incorporate the potential for rapid evolution into your mathematical models. For example, model predator-prey-like dynamics between the therapy and the tumor cell population, where evolutionary changes in one drive ecological changes in the other [17].

- Design Evolution-Informed Dosing Schedules: Use adaptive therapy principles, where dosing is modulated to maintain a population of therapy-sensitive cells that can outcompete resistant ones, rather than always aiming for maximum cell kill.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between the Hill equation and the Emax model for dose-response analysis?

Both models are used to describe dose-response relationships, but the Emax model is a generalization of the Hill equation. The standard Hill equation assumes the effect starts at zero when the dose is zero [13]. In contrast, the Emax model includes an additional parameter (Eâ‚€) to represent the baseline effect at zero dose, making it more flexible for real-world data where a background effect may be present [13]. The Emax model is considered the most common non-linear model in drug development [13].

FAQ 2: How can mathematical modeling improve dose optimization for oncology combination therapies, as encouraged by Project Optimus?

Project Optimus emphasizes the need for thorough dose optimization rather than simply establishing a maximum tolerated dose [18] [19]. Mathematical modeling is central to this by:

- Integrating Diverse Data: Leveraging non-clinical pharmacology, safety data, and early clinical results to build a holistic picture of the dose-response relationship [19].

- Informing Trial Design: Using model-informed drug development (MIDD) to simulate different dosing schedules and combinations, helping to select the most informative doses for clinical trials and reducing the number of patients exposed to potentially subtherapeutic or overly toxic regimens [19].

- Supporting the "Totality of Evidence": Providing a quantitative framework to justify the selected combination dose to regulators, based on a balance of efficacy and safety [19].

FAQ 3: Why might the infection risk from a total pathogen dose be overestimated if it is administered all at once versus over time?

Traditional dose-response models often assume each pathogen particle carries an independent risk, ignoring immune system dynamics [14]. In reality, the immune system has effectors (e.g., antibodies, macrophages) that can engage and eliminate pathogens. When a dose is spread over time, the immune system has a chance to neutralize earlier arrivals and replenish its effector capacity, reducing the probability that any single pathogen will establish an infection [14]. A model that incorporates these dynamics shows that a dose of 313 Cryptosporidium parvum pathogens given at once had an infection risk of 0.66, but when the same dose was spread over a 100-fold longer window, the risk dropped to 0.09 [14].

FAQ 4: How does tumor heterogeneity drive resistance to combination cancer therapies?

Tumor heterogeneity provides the "fuel for resistance" [16]. A tumor is not a uniform mass of identical cells but a collection of subclones with distinct molecular signatures [16].

- Pre-existing Resistance: Some subclones may harbor intrinsic resistance mutations to one or more drugs in the combination regimen before treatment even begins.

- Therapeutic Selection Pressure: The therapy kills the dominant, drug-sensitive subclones, but inadvertently selects for and allows the expansion of pre-existing resistant minor subclones.

- Acquired Resistance: Under the selective pressure of therapy, some tumor cells may evolve new resistance mechanisms, for instance, through genomic instability [16].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Key Parameters in Common Dose-Response Models

| Parameter | Definition | Interpretation in Therapy Development |

|---|---|---|

| ECâ‚…â‚€ / ICâ‚…â‚€ | The dose or concentration that produces half of the maximal effect or inhibition. | A measure of potency; a lower value indicates greater potency. |

| Eₘâ‚â‚“ | The maximum achievable effect of the drug. | A measure of efficacy; the theoretical upper limit of the drug's response. |

| Hill Coefficient (n) | Describes the steepness of the dose-response curve. | Reflects cooperativity or the number of molecules binding to a receptor; a steeper curve suggests a narrower therapeutic window. |

| Eâ‚€ | The baseline effect in the absence of the drug. | Accounted for in the Emax model; represents the system's background activity [13]. |

Table 2: Impact of Exposure Dynamics on Infection Risk (Modeling Data)

This table summarizes findings from a model that incorporates immune effector dynamics, demonstrating how the same total dose administered over different time windows leads to different infection risks [14].

| Pathogen | Total Dose | Temporal Exposure Window | Model-Predicted Infection Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium parvum | 313 pathogens | Single, instantaneous dose | 0.66 (66%) |

| Cryptosporidium parvum | 313 pathogens | Spread over 100x longer window | 0.09 (9%) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fitting a Dose-Response Curve to In Vitro Combination Therapy Data

Objective: To quantitatively assess the synergy between two drugs (Drug A and Drug B) using the Hill equation.

Materials:

- Cell line of interest

- Drug A and Drug B stock solutions

- Cell culture plates (96-well)

- Cell viability assay kit (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo)

Methodology:

- Plate Cells: Seed cells at an optimized density in a 96-well plate and allow them to adhere overnight.

- Prepare Drug Dilutions: Create a matrix of serial dilutions for Drug A and Drug B, covering a range from zero effect to maximum effect (e.g., 0.1 nM to 100 µM).

- Apply Treatment: Apply the drug combinations to the cells. Include controls for no treatment (vehicle) and single-agent treatments for both drugs.

- Incubate: Incubate the plate for a predetermined period (e.g., 72 hours).

- Measure Response: Add the viability assay reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions and measure the signal (e.g., absorbance, luminescence).

- Data Analysis:

- Normalize the data to the vehicle control (100% viability) and a positive control for death (0% viability).

- For each drug combination, fit the data to the Hill equation: ( E = E{max} \times [D]^n / (EC{50}^n + [D]^n) ) where (E) is the effect, ( [D] ) is the drug concentration, (E{max}) is the maximal effect, (EC{50}) is the half-maximal effective concentration, and (n) is the Hill coefficient [13].

- Use software (e.g., Prism, BMDS) to perform nonlinear regression and extract the ECâ‚…â‚€ and Eₘâ‚â‚“ for the combination and individual drugs.

Protocol 2: Longitudinal Tracking of Tumor Heterogeneity via Liquid Biopsy

Objective: To monitor the clonal evolution of a tumor in response to combination therapy using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood samples.

Materials:

- Blood collection tubes (e.g., Streck cfDNA tubes)

- cfDNA extraction kit

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform (e.g., for targeted panel sequencing)

- Bioinformatics pipeline for variant calling and clonal analysis

Methodology:

- Baseline Sample Collection: Draw a blood sample from the patient prior to initiating therapy.

- On-Treatment Sampling: Collect serial blood samples at predefined time points during treatment (e.g., every cycle, at suspected progression).

- cfDNA Isolation: Process the blood samples to isolate plasma, then extract cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from the plasma.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare NGS libraries using a panel that targets genes relevant to the cancer type and known resistance mechanisms. Sequence the libraries to high coverage.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Map sequencing reads to the reference genome and call somatic variants (single nucleotide variants, indels, copy number alterations).

- Estimate the variant allele frequency (VAF) for each mutation.

- Track the changes in VAF for each mutation over time. The emergence or expansion of a clone with specific mutations indicates selection and the development of resistance [16].

- Correlation with Clinical Response: Integrate the ctDNA clonal dynamics data with the patient's radiological and clinical response to understand the drivers of treatment success or failure.

Conceptual Diagrams

DOT Code for Eco-Evolutionary Feedback in Therapy

DOT Code for Dose-Response Model Comparison

DOT Code for Tumor Heterogeneity and Therapy Resistance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Dose Software (BMDS) | Provides a suite of statistical models for dose-response analysis and benchmark dose estimation, widely used in regulatory toxicology and risk assessment [13] [15]. |

| Method of Regularized Stokeslets (MRS) | A computational fluid dynamics method used to model locomotion and fluid-structure interactions at small scales (e.g., bacterial movement), which can inform on drug delivery dynamics [20]. |

| Immersed Boundary (IB) Method | A numerical framework for simulating fluid-structure interaction, useful for modeling biological processes like cilia-driven flow or blood flow, with applications in therapeutic distribution [20]. |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Assays | Enable non-invasive, longitudinal monitoring of tumor burden and clonal evolution through blood draws, critical for assessing temporal heterogeneity and therapy response [16]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Kits | Allow for the profiling of gene expression in individual cells within a tumor, revealing hidden heterogeneity, cell states, and potential resistance pathways not visible in bulk analyses [16]. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling Software | Used to simulate the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of drugs, helping to translate external doses into internal target tissue concentrations for more accurate dose-response modeling [15]. |

| Tecarfarin | Tecarfarin|Novel VKA Anticoagulant|For Research |

| Tenellin | Tenellin |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common technical and strategic challenges researchers face when implementing Project Optimus principles in the development of combination therapies, with a focus on mathematical modeling approaches.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Our first-in-human trial did not reach a Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD). How can we justify a dose for further development without this traditional benchmark?

- Answer: The absence of an MTD is common with modern targeted therapies. A robust justification should be based on the Totality of Evidence [21] [22]. This includes:

- Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Data: Demonstrate target saturation or engagement using validated biomarkers. Model the exposure-response relationship to identify the dose that achieves maximal biological effect [23] [1].

- Preliminary Efficacy Signals: Use early efficacy endpoints (e.g., overall response rate, effect on circulating tumor DNA) to inform dose selection [1].

- Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD): Leverage quantitative approaches like quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) or exposure-response modeling to integrate all available nonclinical and clinical data, predicting effective doses for later-stage trials [21] [22].

- Answer: The absence of an MTD is common with modern targeted therapies. A robust justification should be based on the Totality of Evidence [21] [22]. This includes:

FAQ 2: How do we design an efficient trial to compare multiple doses without making the study too large or costly?

- Answer: Implement adaptive and seamless trial designs [22].

- Adaptive Designs: Utilize designs that allow for pre-planned, interim analyses to drop underperforming dose arms based on efficacy or safety, thereby concentrating resources on the most promising doses [21].

- Seamless Designs: Combine traditionally distinct phases (e.g., Phase 1b and Phase 2) into a single trial, allowing for more efficient enrollment and the collection of long-term data on the selected dose(s) [22].

- Backfill Cohorts: In early-phase trials, add patients to lower dose levels ("backfilling") once safety has been established at higher doses. This efficiently generates rich PK/PD and preliminary activity data across a wider dose range [1].

- Answer: Implement adaptive and seamless trial designs [22].

FAQ 3: For a combination therapy, how can we optimize the dose of both drugs without running an unfeasible number of arms?

- Answer: This is a multidimensional problem best addressed with a model-informed, fit-for-purpose strategy [21].

- Leverage Monotherapy Data: Use well-characterized exposure-response and exposure-safety models for each individual agent to inform the combination design [22].

- Factorial Designs: Employ designs that test a limited number of dose levels for each drug in combination, using modeling to interpolate and predict outcomes for untested dose pairs [21].

- Clinical Utility Index (CUI): Use a CUI to quantitatively integrate efficacy and safety data from the combination arms, creating a composite score to objectively identify the optimal dose pair that balances benefit and risk [1].

- Answer: This is a multidimensional problem best addressed with a model-informed, fit-for-purpose strategy [21].

FAQ 4: How should we handle patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and quality-of-life data in our dose-optimization models?

- Answer: PROs are a critical component of the tolerability assessment under Project Optimus [24].

- Systematic Collection: Integrate validated PRO instruments into your clinical trials to capture symptomatic adverse events and the impact of treatment on physical function and quality of life [22].

- Quantitative Integration: Model the relationship between drug exposure and the time to deterioration or improvement in PRO scores. This data can be incorporated into a Clinical Utility Index alongside traditional efficacy and safety endpoints to provide a patient-centric view of the optimal dose [24] [22].

- Answer: PROs are a critical component of the tolerability assessment under Project Optimus [24].

Quantitative Data on Dose Optimization

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings and methodological approaches relevant to dose optimization.

Table 1: Evidence for the Need of Improved Dose Optimization in Oncology

| Data Point | Finding | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dose Modification Rate | 48% of patients in Phase 3 trials of molecularly targeted agents required dose modifications from the recommended dose. | Analysis of tolerability in phase 3 trials [23] |

| Post-Marketing Dose Reevaluation | The FDA has required additional studies to re-evaluate the dosing of over 50% of recently approved cancer drugs. | FDA observations on recent approvals [1] |

| Dose Reduction/Interruption | Registration trials for new oral targeted agents (2010-2020) showed median dose reduction and interruption rates of 28% and 55%, respectively. | Review of 59 newly approved oral molecular entities [21] |

Table 2: Key Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) Approaches for Dose Optimization

| Modeling Approach | Primary Function | Application in Combination Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure-Response (E-R) Modeling | Correlates drug exposure (e.g., AUC, C~trough~) with efficacy or safety endpoints to predict the response at different doses. | Can be developed for each drug in a combination to understand their individual and potentially synergistic contributions. |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Incorporates biological mechanisms to predict drug effects. Uses limited clinical data to understand complex interactions. | Highly valuable for simulating the interaction between two drugs and identifying dose regimens that maximize synergy and minimize overlapping toxicities [22]. |

| Clinical Utility Index (CUI) | A quantitative framework that creates a composite score by integrating multiple endpoints (efficacy, safety, PROs) to rank different doses. | Ideal for objectively selecting the optimal dose pair from a combination trial by balancing the efficacy and safety profiles of both agents [1]. |

| Population PK (PopPK) Modeling | Describes the pharmacokinetics and sources of variability in a patient population. | Can identify covariates (e.g., organ function, drug-drug interactions) that may necessitate dose adjustments in a combination setting [22]. |

Experimental Protocols for Dose Optimization

Protocol 1: Randomized Dose Comparison in an Early-Phase Trial

Objective: To select the optimal dose for registrational trials by comparing at least two doses for efficacy and safety.

Methodology:

- Dose Selection: Based on Phase 1a data, select two or more doses for head-to-head comparison. The doses should be sufficiently spaced (e.g., 2-3 fold apart in exposure) and could include the estimated minimum biologically effective dose (MBED) and the highest tolerable dose [23] [1].

- Study Population: Enroll patients from the intended later-phase population. Expansion cohorts in Phase 1 can be used for this randomization.

- Randomization: Randomize patients to the selected dose arms. The study does not need to be powered for a formal statistical superiority comparison but must be sufficiently sized to characterize the shape of the dose-response and dose-toxicity relationships [23].

- Endpoint Assessment: Collect comprehensive data on:

- Efficacy: Primary efficacy endpoints (e.g., ORR) and relevant biomarker data (e.g., ctDNA) [1].

- Safety: Incidence of adverse events, dose reductions, interruptions, and discontinuations.

- PK/PD: Intensive sampling for exposure assessment and target engagement biomarkers.

- PROs: Patient-reported outcomes on symptoms and quality of life [22].

- Data Integration & Dose Selection: Analyze the totality of evidence. Use a Clinical Utility Index (CUI) or similar quantitative framework to integrate the efficacy and safety data and select the dose with the most favorable benefit-risk profile for the registrational trial [1].

Protocol 2: Model-Informed Dose Optimization for a Combination Therapy

Objective: To identify the optimal dose pair for two investigational drugs (Drug A and Drug B) used in combination using quantitative modeling.

Methodology:

- Prior Knowledge: Develop robust PopPK and exposure-response models for Drug A and Drug B as monotherapies using all available nonclinical and clinical data [22].

- Combination Trial Design: Initiate a clinical trial testing a limited set of dose pairs (e.g., two dose levels of Drug A combined with two dose levels of Drug B).

- Data Collection: Collect rich PK, PD, efficacy, and safety data from all arms of the combination trial.

- Model Development & Simulation:

- Develop a QSP model that incorporates the mechanisms of action of both drugs and their potential interactions [22].

- Calibrate and verify the model using the clinical data from the combination trial.

- Use the verified model to simulate a wide range of untested dose pairs for Drug A and Drug B, predicting key efficacy and safety outcomes for each virtual pair.

- Dose Selection: Identify the simulated dose pair that maximizes predicted efficacy while maintaining a tolerable safety profile. This model-informed recommendation can then be validated in a subsequent expansion cohort or registrational trial.

Visualizing the Project Optimus Workflow and Modeling Strategy

Project Optimus vs Legacy Dose Finding

MIDD Toolkit for Dose Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Project Optimus-Aligned Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Dose Optimization | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Validated PD Biomarker Assays | To quantitatively measure target engagement and biological effect of the drug at different dose levels. | Immunoassays or flow cytometry to confirm receptor occupancy or modulation of a downstream signaling pathway, helping to define the minimum biologically effective dose (MBED) [23] [1]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | For high-sensitivity quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in biological matrices (plasma, tissue) to support robust PK analysis. | Generating concentration-time data for population PK modeling, which is foundational for all exposure-response analyses [22]. |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Assays | To serve as an early, dynamic biomarker of tumor response and resistance. | Tracking changes in ctDNA levels in response to different doses in early-phase trials to inform efficacy signals before traditional radiological assessments [1]. |

| Modeling & Simulation Software | Platforms for performing complex quantitative analyses, including population PK, exposure-response, and QSP modeling. | Using software like R, NONMEM, or specialized QSP platforms to integrate all data sources, simulate untested doses, and identify the optimal dose with a superior benefit-risk profile [21] [22]. |

| Validated Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Instruments | To systematically capture the patient's perspective on treatment tolerability and impact on quality of life. | Integrating PRO data into safety assessments and the Clinical Utility Index to ensure the selected dose is not only effective but also tolerable from the patient's viewpoint [24] [22]. |

| APN-C3-NH-Boc | APN-C3-NH-Boc|Alkyl/Ether PROTAC Linker | APN-C3-NH-Boc is an alkyl/ether PROTAC linker with an alkyne handle for click chemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| THK-523 | THK-523, CAS:1573029-17-0, MF:C17H15FN2O, MW:282.32 | Chemical Reagent |

The Modeler's Toolkit: Key Approaches and Clinical Applications in Combination Therapy

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers using mathematical modeling to optimize combination therapy doses. The guidance is framed within the context of a broader thesis on this topic.

Frameworks for Combination Therapy Optimization

The table below summarizes the core modeling frameworks used in therapeutic research.

| Modeling Framework | Core Principle | Advantages for Combination Therapy | Key Challenges | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE) | Represents system states as continuous variables changing over time via differential equations. [25] | Well-established for PK/PD; efficiently describes drug concentration and effect. [26] | Difficult to capture spatial heterogeneity and individual entity history. [26] | Modeling pharmacokinetics and signaling pathways (e.g., NF-κB, STAT3). [25] [27] |

| Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) | Models system from the bottom-up through interactions of discrete, autonomous agents. [26] | Naturally captures tumor heterogeneity, spatial effects, and cell-cell interactions. [26] | High computational cost; parameterization and validation can be complex. [26] | Simulating tumor-immune cell interactions and therapy responses in the tumor microenvironment. [26] |

| Multiscale Modeling | Integrates multiple models operating at different biological scales (e.g., molecular, cellular, tissue). [28] | Mechanistically links drug pharmacokinetics to cellular and tissue-level responses. [28] | Designing scale-coupling functions; high computational complexity. [29] | Predicting in vivo efficacy of CAR-T cell therapies in solid tumors. [28] |

| TJ191 | TJ191|Selective Anti-Cancer Small Molecule|RUO | TJ191 is a potent cytostatic/cytotoxic agent for T-cell leukemia/lymphoma research. It targets cells with low TβRIII. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| Tos-PEG4-acid | Tos-PEG4-acid, MF:C16H24O8S, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions

ODE Model Troubleshooting

Q: My ODE model of a pro-/anti-inflammatory signaling pathway fails to resolve inflammation. What could be wrong?

A: A lack of resolution often points to missing negative feedback loops. Ensure your model includes key regulatory components. For instance, in a macrophage polarization model, the inclusion of the SOCS (Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling) family of proteins is critical. SOCS1 and SOCS3 act as part of negative feedback loops that resolve both the M1 and M2 pathways. SOCS3 inhibits the transcription of TNFα mRNA, and both SOCS1 and SOCS3 inhibit the activation of STAT3. Without these, the model may not definitively resolve the inflammatory response. [25]

Q: How can I improve the generalizability of my PK-ODE model to predict untested dosing regimens?

A: Consider moving beyond traditional nonlinear mixed-effects models. A cutting-edge approach is to use Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural-ODE). This method uses a neural network to learn the dynamics of the ODE system directly from data. Studies have shown that Neural-ODE models demonstrate superior performance in predicting pharmacokinetic profiles for dosing regimens that were not part of the training data, a common limitation of other machine learning and traditional PK models. [30]

Agent-Based Model Troubleshooting

Q: I am getting a "Type mismatch: cannot convert from [TYPEA] to [TYPEB]" error in my agent-based model. How do I fix it?

A: This is a common compile-time error where a variable is assigned a value of an incorrect type. [31] For example, a variable defined as a double (a decimal number) might be used in a context that requires a boolean (true/false) value, such as the condition for a SelectOutput block.

- Solution: Carefully check the defined type of the variable causing the error and the type expected by the function or block where it is used. Correct the type declaration or the value assignment to ensure they match. [31]

A: This is a runtime error related to the model's logic in a discrete-event flowchart. It indicates that an agent (e.g., a cell) has reached a port (an exit point) in a block, but there is no connected block for the agent to move to next. [31]

- Solution: Review your flowchart connectivity. Ensure the port in question is connected to a subsequent block, such as a

DelayorSinkblock, to handle the agent. [31]

Multiscale Model Troubleshooting

Q: What is the most efficient design pattern for coupling different simulators in a multiscale model?

A: A robust software science co-design pattern uses five modules: one launcher, two simulators, and two transfer modules. Each transfer module contains an interface for receiving data, an interface for sending data, and a critical transformation process. The transformation process is responsible for converting the data from one scale into a format that is meaningful at the other scale (e.g., converting population-level average signals to individual cell stimuli and vice versa). This design separates scientific (the transformation logic) from technical (data exchange) concerns, improving efficiency and maintainability. [29]

Q: Our multiscale model of CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors is not showing efficacy in virtual patients. What factors should we investigate?

A: The lack of efficacy in silico can reveal critical biological barriers. Use your model for sensitivity analysis to identify the most influential parameters. Key factors to investigate include:

- CAR-T cell tumor infiltration: The insufficient presence of CAR-T cells in the tumor tissue is a major barrier. [28]

- Tumor antigen heterogeneity: Variable expression of the target antigen can lead to immune escape. [28]

- Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment (TME): Factors like regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and immunosuppressive cytokines can inactivate CAR-T cells. [28]

- CAR-T product parameters: Explore the impact of CAR affinity, CAR density on the T cell surface, and the ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells in the infused product. [28]

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Building a QSP Model for CAR-T Cell Therapy

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a Multiscale Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) model to predict the efficacy of CAR-T therapies in solid tumors. [28]

- Define Model Scope and Biology: Identify key actors: CAR-T cells (CD4+, CD8+), tumor cells with antigen expression levels, and major components of the tumor microenvironment (e.g., immunosuppressive cells).

- Formulate the Mathematical Framework:

- Use ODEs to describe the cellular kinetics of CAR-T cells (expansion, contraction, persistence).

- Use ABM rules or PDEs to capture spatial distribution and cell-cell contact dynamics within the tumor.

- Integrate a PK/PD model for any co-administered drugs in a combination therapy.

- Calibrate with Multimodal Data:

- In vitro: Use data from co-culture assays of CAR-T cells and tumor cells to calibrate killing kinetics and cytokine release.

- In vivo: Use animal model data (e.g., murine xenografts) to calibrate CAR-T biodistribution, tumor volume dynamics, and overall survival.

- Generate a Virtual Patient Population: Create a virtual cohort by sampling key system parameters (e.g., tumor burden, antigen expression level, immune contexture) from distributions informed by clinical data.

- Simulate and Optimize Dosing: Run prospective simulations with the virtual patients to test different dosing strategies, such as flat dosing versus step-fractionated dosing, to identify regimens that maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity. [28]

Protocol 2: Co-Simulation of Brain Models Across Scales

This protocol describes a workflow for co-simulating a macroscopic brain network model with a microscopic spiking neural network. [29]

- Setup Simulators: Establish two specialized simulators: The Virtual Brain (TVB) for the whole-brain network model and NEST for the spiking neural network model of a specific region (e.g., hippocampus CA1).

- Implement the Co-Design Pattern:

- The Launcher starts both simulators and handles global coordination.

- Simulator A (TVB) runs its simulation for a short time window.

- Transfer Module A→B receives the macroscopic output from TVB (e.g., average neural population activity). Its transformation process converts this into input for the micro-scale model (e.g., synaptic currents to individual neurons).

- Simulator B (NEST) runs its simulation for the same time window, using the transformed input.

- Transfer Module B→A receives the microscopic output from NEST (e.g., aggregated spiking activity). Its transformation process converts this back into a format for the macro-scale model (e.g., an input current to the neural mass model in TVB).

- Validate with Multiscale Data: Compare the co-simulation output with empirical data that spans scales, such as simultaneous electrocorticography (ECoG) and local field potential (LFP) recordings. [29]

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and platforms used in advanced pharmacological modeling.

| Tool / Platform | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Stan (with CmdStanR) [27] | Statistical Inference Engine | Bayesian parameter estimation for complex ODE models, such as pharmacokinetic models. |

| AnyLogic [31] | Commercial Modeling Platform | Integrated environment for developing agent-based, discrete-event, and system dynamics models. |

| The Virtual Brain (TVB) [29] | Open-Source Platform | Simulation of whole-brain network dynamics based on individual neuroimaging-derived connectomes. |

| NEST [29] | Open-Source Simulator | Simulation of large-scale spiking neural network models at the level of individual neurons and synapses. |

| Neural-ODE [30] | Machine Learning Method | Learning the structure and parameters of differential equation systems directly from time-series data. |

Model Diagrams and Workflows

ODE Model of Macrophage Polarization

Multiscale Co-Simulation Design Pattern

ABM Model for Tumor-Immune System

Leveraging Exposure-Response and Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Do QSP models require vast amounts of data to be built? No. While building a QSP model from scratch requires data to inform its parameters, using pre-existing, literature-based models for well-understood systems (e.g., renal function, bone metabolism) can significantly reduce data requirements. You primarily need pharmacokinetic (PK) data and information on the drug's mechanism of action or biomarkers. [32]

Q2: Is QSP modeling accepted by regulatory agencies like the FDA? Yes. QSP is increasingly used to support Investigational New Drug (IND), New Drug Application (NDA), and Biologics License Application (BLA) submissions. Submissions incorporating QSP models have been rising, and they have been used, for instance, to evaluate dosing regimens in regulatory submissions. [32]

Q3: What is the main difference between QSP and traditional population PK/PD (popPK/PD) models? PopPK/PD models typically describe the empirical relationship between plasma drug concentrations and a pharmacodynamic effect. In contrast, QSP models mechanistically describe the relationship between drug concentrations at the site of action and the resulting effects, accounting for complex biological networks, multiple sequential processes, endogenous substrates, and feedback mechanisms. This makes QSP particularly valuable for simulating combination therapies with different mechanisms of action. [32]

Q4: How can I have confidence in a QSP model's predictions, especially with many uncertain parameters? Using Virtual Populations (VPs) is a key method for assessing confidence. By running simulations across a family of parameter sets, you can generate a distribution of predictions. You can then quantify the robustness of a qualitative prediction (e.g., a drug-scheduling effect) by determining in what proportion of virtual population simulations the effect persists, compared to a null hypothesis. [33]

Q5: Can QSP models be built if the drug's mechanism of action is not fully understood? Yes. Gaps in knowledge can be addressed by hypothesizing a mechanism, checking the model against available data, and iteratively refining it with new experimental results. Literature searches for similar compounds and collaboration with expert consultants are crucial for filling these gaps. [32]

Q6: At what stage of drug development can QSP be applied? QSP can add value at all stages, from early discovery to late-stage development. Early on, it can aid target validation and candidate selection. Later, it can optimize clinical trial design, evaluate subpopulations, and support dosage decisions for registrational trials without the need for new clinical studies. [32] [34]

Troubleshooting Common QSP Challenges

The table below outlines common technical challenges encountered during QSP modeling and practical solutions to address them.

| Challenge | Description & Potential Solutions |

|---|---|

| Parameter Identifiability & Estimation | Description: It can be difficult to uniquely estimate a large number of parameters in complex models, leading to uncertainty. [35]Solutions:• Use profile likelihood methods to check if parameters are practically identifiable. [35]• Employ Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approaches to explore the posterior distribution of parameters and identify those with wide, unconstrained distributions. [35] |

| Model Validation for Qualitative Predictions | Description: Standard pharmacometric validation methods (e.g., goodness-of-fit plots) are not always suitable for assessing QSP models designed for qualitative, systems-level predictions. [33]Solutions:• Use Virtual Populations to generate distributions of predictions and statistically quantify the robustness of qualitative findings (e.g., "in 95% of simulations, the sequential regimen was superior"). [33] |

| Balancing Granularity & Complexity | Description: Determining the right level of biological detail ("granularity") is difficult. Too much detail makes the model complex and slow; too little reduces predictive power. [35]Solutions:• Let the research question guide the required granularity. [35]• Use model reduction techniques to lump variables and simplify large network models where possible. [35] |

| Integrating Disparate Data Sources | Description: QSP models are often constrained by data from multiple sources (in vitro, in vivo, clinical) and scales (molecular, cellular, organ), which can be heterogeneous. [33]Solutions:• The model itself serves as a framework to integrate this multi-scale data. [34] A collaborative, iterative cycle with experimental labs is essential to fill knowledge gaps and refine the model. [35] |

Featured Experiment: Optimizing a Breast Cancer Combination Immunotherapy Regimen

This section details a specific research experiment that leveraged mathematical modeling to optimize doses for combination therapy, directly supporting the thesis context.

Experimental Objective

To develop and validate a mathematical model that optimizes the medication regimen for combining an mRNA-based cancer vaccine with anti-CTLA-4 antibody therapy for breast cancer, aiming to maximize tumor growth inhibition while minimizing immunotoxic side effects. [36]

Detailed Methodology

Model Development: A mathematical model was constructed to describe the interactions between the mRNA-based vaccine, anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, and the tumor immune microenvironment. The model likely includes components for immune cell activation, tumor cell killing, and inhibitory signaling via CTLA-4. [36]

Parameter Estimation: The model was parameterized using experimental data. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method was employed to estimate model parameters, a robust approach for dealing with parameter uncertainty in complex biological models. [36]

Model Simulation & Validation: Simulations from the parameterized model were compared against experimental results not used in the training phase to assess the model's predictive capability and build credibility. [36]

Regimen Optimization: The gradient descent method, an optimization algorithm, was designed and applied to the validated model. This algorithm systematically adjusted the dosing variables (timing and amount) to find the regimen that best achieved the dual goals of inhibiting tumors and reducing side effects. [36]

- The optimized regimen dictated that the anti-CTLA-4 antibody should be administered after the vaccination. [36]

- Within a safe range, the dose of the antibody should positively correlate with the dose of the vaccine. [36]

- The study provides a theoretical basis for selecting combination therapy regimens in clinical trials, moving beyond trial-and-error approaches. [36]

Logical Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the sequential, iterative workflow of the featured QSP experiment for optimizing combination therapy.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The table below lists key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for conducting QSP research like the featured experiment.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A computational algorithm for estimating parameters in complex models, especially when facing uncertainty. It explores the probability distribution of parameters given the data. [36] |

| Gradient Descent Method | An optimization algorithm used to find the minimum of a function. In this context, it was designed to find the dosing regimen that minimizes tumor size and side effects. [36] |

| Virtual Populations (VPs) | A family of model parameter sets used to account for uncertainty and biological variability. VPs generate distributions of predictions, allowing researchers to quantify the robustness of results. [33] |

| Pre-Validated QSP Model Libraries | Existing models for specific biological systems (e.g., cardiac action potential, liver disease) that can be adapted for new projects, saving significant time and resources compared to building from scratch. [32] [37] |

| Model Credibility Assessment Framework | A set of criteria (e.g., from the ASME or EMA) used to evaluate the credibility of computational models for a specific context of use, which is critical for regulatory submissions. [38] |

FAQs: Foundational Concepts in In Silico Therapy Design

Q1: What is the core value of using mathematical models in CAR-T and Targeted Radionuclide Therapy (TRT) development?

Mathematical models provide a systematic and quantitative framework to understand the complex, dynamic interactions between therapy and cancer, which are often difficult or costly to probe experimentally [39] [40]. They enable researchers to simulate treatment outcomes in silico, offering a resource-saving method to test hypotheses, optimize dosing schedules, and personalize treatment protocols before moving to clinical trials [39] [5] [41]. For combination therapies, models are crucial for determining the optimal timing and sequence of treatments [42].

Q2: What are the primary types of computational models used in this field, and when should I use them?

The choice of model depends on the research question and the scale of the biological process being investigated.

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Agent-Based Models (ABM) | Simulates actions and interactions of autonomous entities (e.g., individual cells) in a spatial environment to explore emergent system behavior [39]. | Studying the effects of spatial heterogeneity, cell-cell contact interactions, and the emergence of resistant cell populations [39]. |

| Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Models | Describes system dynamics through equations that define the rates of change of population-level quantities (e.g., tumor cell count, CAR-T cell count) over time [41] [42]. | Modeling bulk population dynamics, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), and predicting overall tumor burden [41] [42]. |

| Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PKPD) Models | A class of ODE models that specifically links the pharmacokinetics (what the body does to the drug) to the pharmacodynamic response (what the drug does to the body) [41]. | Predicting the relationship between drug/CAR-T affinity, antigen abundance, tumor cell depletion, and therapy expansion [41]. |

| Monte Carlo Simulations | Uses random sampling to model the probability of different outcomes in processes that are inherently stochastic [43]. | Simulating radiation track structures and calculating the precise number and complexity of DNA damage events caused by radionuclides at a cellular level [43]. |

Q3: What key biological determinants does modeling suggest are critical for CAR-T cell therapy success?

Computational studies have highlighted several critical factors:

- CAR-T Cell Persistence and Expansion: The ability of CAR-T cells to survive and proliferate in vivo is a major determinant of long-term remission and preventing relapse [41].

- Tumor Antigen Heterogeneity: Intratumoral heterogeneity in antigen expression is a leading cause of therapeutic resistance. Models show that cells with low antigen expression can form a "shield," protecting high-antigen cells from eradication [39].

- Tumor Proliferation Rate: The intrinsic growth rate of a tumor is a key parameter in scheduling combination therapies, with faster-proliferating tumors requiring different timing between TRT and CAR-T administration [42].

Q4: How can in silico models help overcome antigen escape in CAR-T therapy for solid tumors?

Models are used to design and test strategies to overcome antigen escape, a phenomenon where tumor cells stop expressing the target antigen. A prominent strategy is multi-antigen recognition, such as syn-Notch receptors, where an engineered receptor induces expression of a CAR upon recognition of a primary antigen, creating T-cells that can target two different antigens [39]. While powerful, models also highlight that this approach can increase the risk of on-target, off-tumor toxicity, necessitating careful dosimetry [39].

Q5: What are the principal considerations for optimizing Targeted Radionuclide Therapy (TRT) based on modeling?

Mathematical models of TRT emphasize several optimization principles [44]:

- Nuclide-to-Antibody Ratio: The density of radioconjugates on cancer cells determines radiation energy deposition. A low ratio or an excess of unlabeled antibodies can saturate receptors and mitigate cancer cell damage.

- Cancer Binding Capacity-Based Dosing: Doses significantly exceeding the total number of target receptors on cancer cells should be avoided, as the excess circulates in the bloodstream, contributing to toxicity without enhancing efficacy.

- Particle Range-Guided Multi-Dosing: For short-range alpha emitters, an initial dose to saturate cancer cells allows subsequent doses to target viable cells that continue expressing receptors, improving dose redistribution.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inadequate Tumor Control in CAR-T Cell Therapy Simulations

Problem: Your model predicts poor tumor control or early relapse after CAR-T cell therapy.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low CAR-T Cell Persistence | Check the simulated dynamics of activated vs. non-activated CAR-T cells over time. Is the population declining rapidly? [41] | Model the administration of "next-generation" CARs (e.g., 4th gen TRUCKs) that include cytokine genes to enhance persistence and memory formation [40]. |

| High Antigen Heterogeneity | Analyze the spatial distribution and phenotypic evolution of tumor cell clones, particularly those with low antigen expression [39]. | Simulate a switch to a multi-antigen targeting strategy (e.g., syn-Notch receptor circuits) to overcome heterogeneity and antigen escape [39]. |

| Suboptimal Dosing | Run sensitivity analyses on the initial CAR-T cell dose and the killing rate parameter (k1 in ODE models) [39] [41]. |

Test multiple dosing regimens or model combination therapy with TRT to target antigen-negative cells via bystander effects [39] [42]. |

| CAR-T Cell Exhaustion | Incorporate an "exhausted" state in your model and track its population. Check if the rate of exhaustion upon tumor cell encounter (k2) is too high [42]. |

Investigate the effect of costimulatory domains in your CAR design (e.g., 4-1BB vs. CD28) within the model, as these can influence exhaustion profiles [40]. |

Guide 2: Managing Toxicity and Off-Target Effects in TRT

Problem: Your TRT model shows effective tumor kill but unacceptably high toxicity to healthy tissues, particularly bone marrow.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Unanchored Radionuclides | Quantify the ratio of radionuclides bound to cancer cells versus those circulating freely in the bloodstream over time [44]. | Optimize the injected dose to match the tumor's binding capacity, avoiding large excesses that remain in circulation [44]. |

| Suboptimal Radionuclide Choice | Compare the simulated DNA damage (e.g., DSB/Gbp/decay) and effective range of different radionuclides in your model [43]. | For small tumors/micrometastases, model switching from a beta emitter (e.g., ¹â·â·Lu) to a short-range alpha emitter (e.g., ²²âµAc), which deposits more energy over a smaller distance, sparing surrounding tissues [43]. |

| Inadequate Dosing Schedule | Simulate the cumulative dose to dose-limiting organs (e.g., bone marrow) for single vs. fractionated dosing schedules. | Implement dose fractionation. Splitting the total dose into several smaller administrations can reduce peak toxicity and allow healthy tissue recovery [44]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Building an Agent-Based Model (ABM) to Study CAR-T Therapy Against Heterogeneous Tumors

This protocol is based on the in silico study of tumor-derived organoids [39].

1. Define the Simulation Environment and Initial Conditions:

- Set up a 3D grid (e.g., 1000x1000x1000 µm) with a spherical organoid seeded at the center.

- To model heterogeneity, assign each tumor cell a mutant oncoprotein value drawn from a normal distribution (e.g., mean=1, SD=0.25, range 0-2). Discretize cells into types based on this value (e.g., Type 1: 1.5-2.0, Type 2: 1.0-1.5, etc.) [39].

2. Program Agent Behaviors and Rules:

- Tumor Cells: Proliferation rate and immunogenicity should scale proportionally with the oncoprotein value

o. Set a threshold (e.g., o < 0.5) below which cells are not recognized by CAR-T cells [39]. - CAR-T Cells: Program rules for random motility, activation upon contact with a tumor cell (if

o> threshold), cytotoxic killing, and proliferation post-activation.

3. Implement Therapy and Run Simulations:

- Introduce a defined dose of CAR-T cells at a specific time point (e.g., day 7).

- Run simulations for different T-cell-to-cancer ratios and dosing strategies (single vs. multiple doses).

4. Analyze Outputs:

- Track total tumor cell count and mean oncoprotein expression over time.

- Observe spatial structures, such as the formation of a "shield" of low-antigen cells protecting high-antigen cells [39].

- Quantify the number of "free" CAR-T cells (those that have not engaged a target) as a proxy for potential side-effect risk.

ABM Workflow for CAR-T Therapy

Protocol 2: Implementing a Combined ODE Model for TRT and CAR-T Combination Therapy

This protocol is based on the work combining two previously published models [42].

1. Define Model Variables and Equations: The model typically tracks these populations:

N_T: Non-irradiated tumor cellsN_R: Irradiated tumor cellsN_C: CAR-T cells

The system of ODEs can be structured as follows [42]:

- dNT/dt = ÏNT - H(t-Ï„TRT) * kRxT * NT - H(t-Ï„CAR) * k1 * NT * NC (Change in non-irradiated cells = Growth - TRT effect - CAR-T killing)

- dNR/dt = H(t-Ï„TRT) * kRxT * NT - H(t-Ï„CAR) * k1 * NR * NC - kcl * N_R (Change in irradiated cells = TRT effect - CAR-T killing - Clearance)

- dNC/dt = k2 * (NT + NR) * NC - H(t-τTRT) * kRxC * NC - θ * NC (Change in CAR-T cells = Proliferation - TRT effect - Death)

2. Parameterize the Model:

- TRT Parameters (

k_Rx_T,k_Rx_C,k_cl): Obtain from preclinical TRT studies. For alpha emitters like ²²âµAc, the radiation effect termk_Rxcan be modeled using a linear-quadratic equation with a dose protraction factor [42]. - CAR-T Parameters (

k_1,k_2,θ): Estimate from mouse models.k_1is the killing rate,k_2is the proliferation rate upon tumor encounter, andθis the death rate [42]. - Tumor Parameter (

Ï): Fit from control group tumor growth data.

3. Simulate Combination Therapy:

- Use the Heaviside function

H(t-τ)to turn treatments on at specific timesτ_TRTandτ_CAR. - Run simulations for different sequences (TRT first vs. CAR-T first) and intervals between therapies.

4. Identify Optimal Scheduling:

- The tumor proliferation rate

Ïis a critical parameter. Models suggest that for faster-proliferating tumors, the interval between TRT and CAR-T should be shorter [42].