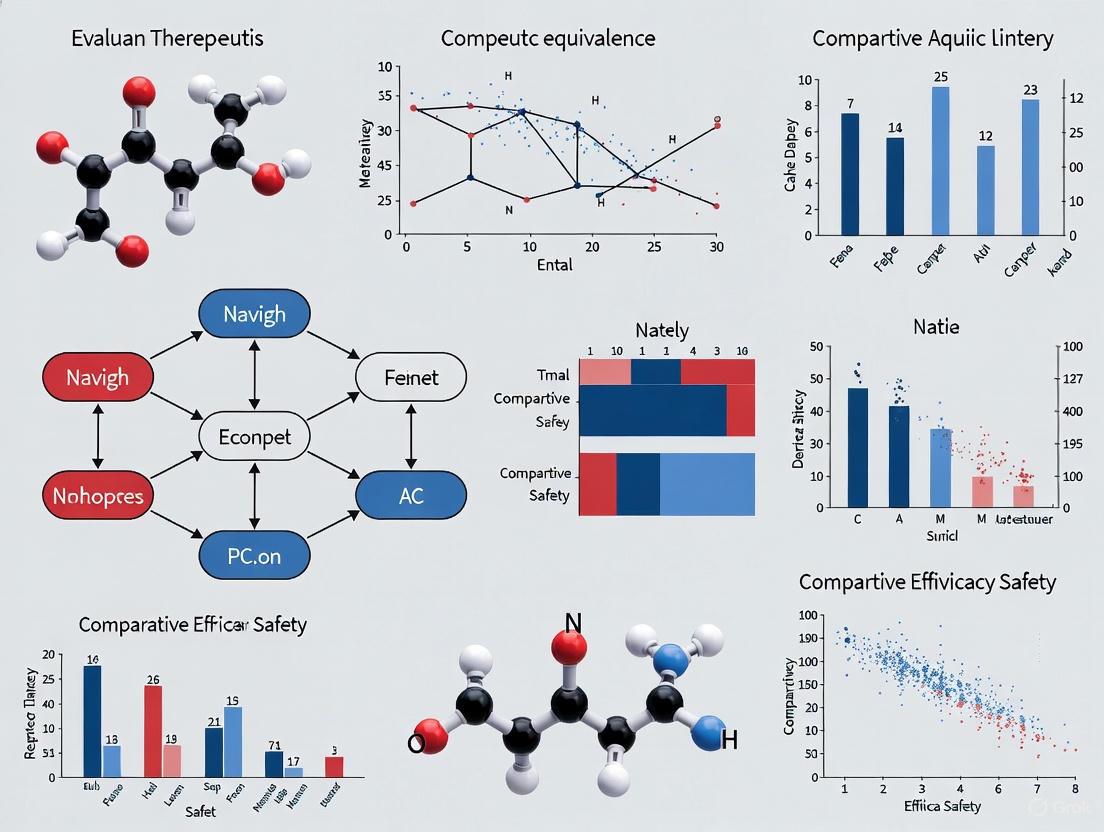

Beyond Direct Comparison: A Modern Framework for Evaluating Therapeutic Equivalence with Network Meta-Analysis

Network meta-analysis (NMA) has become an indispensable tool for comparative effectiveness research, enabling the evaluation of therapeutic equivalence and hierarchy among multiple interventions in the absence of head-to-head trials.

Beyond Direct Comparison: A Modern Framework for Evaluating Therapeutic Equivalence with Network Meta-Analysis

Abstract

Network meta-analysis (NMA) has become an indispensable tool for comparative effectiveness research, enabling the evaluation of therapeutic equivalence and hierarchy among multiple interventions in the absence of head-to-head trials. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the foundational principles, advanced methodologies, and critical appraisal techniques required for robust NMA. Drawing on contemporary case studies from cardiology, oncology, and rare diseases, we explore the entire NMA workflow—from systematic literature review and network feasibility assessment to the application of novel statistical metrics like SUCRA and loss-adjusted expected value for risk-averse decision-making. The content addresses common pitfalls in establishing transitivity, interpreting uncertainty, and validating findings, ultimately empowering scientists to generate reliable evidence for clinical guidelines and health technology assessments.

The Foundations of Therapeutic Equivalence: Core Concepts and When to Use NMA

Defining Therapeutic Equivalence and Treatment Hierarchy in Modern Drug Development

In modern drug development, therapeutic equivalence is a fundamental regulatory and clinical concept. For generic drugs, it is established by demonstrating bioequivalence to a reference listed drug, proving that the generic drug has the same active ingredient, dosage form, strength, and route of administration, and that it is absorbed at the same rate and extent as the innovator product [1]. This principle allows generic manufacturers to utilize an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, bypassing the need for extensive and costly new clinical trials by relying on the FDA's previous finding of safety and efficacy for the reference drug [1].

Beyond the generic drug context, comparing multiple treatment options for a condition requires advanced statistical methodologies. Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) has emerged as a powerful extension of standard pairwise meta-analysis, enabling the simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments that may not have been directly compared in head-to-head clinical trials [2]. By synthesizing both direct and indirect evidence across a network of studies, NMA allows researchers to establish a treatment hierarchy, ranking interventions based on their relative efficacy, safety, or other critical outcomes [3] [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for health technology assessment and clinical guideline development, as it provides comprehensive evidence for decision-making where direct evidence is lacking [3].

Methodological Framework for Network Meta-Analysis

Core Concepts and Definitions

Network meta-analysis relies on several interconnected statistical and epidemiological concepts. The table below defines the key terminology and assumptions essential for conducting a valid NMA.

Table 1: Key Assumptions and Terminology in Network Meta-Analysis

| Term | Definition | Importance in NMA |

|---|---|---|

| Homogeneity | The equivalence of trials within each pairwise comparison in the network [2]. | Assesses variability between studies comparing the same treatments; high heterogeneity may undermine valid pooling of results. |

| Transitivity | The validity of making indirect comparisons, evaluated by reviewing the similarity of trial characteristics across the network [2]. | Ensures that the common comparator (e.g., Treatment B in A vs. B and B vs. C) is similar enough to allow a fair indirect comparison between A and C. |

| Consistency | The agreement between direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (via a common comparator) [2]. | Validates the network; significant inconsistency suggests potential violation of transitivity or other biases. |

| Connected Network | A network where there is a path of direct comparisons from each treatment to every other treatment [2]. | A prerequisite for standard NMA; disconnected treatments cannot be compared. |

Experimental Protocol for Conducting a Network Meta-Analysis

The following workflow outlines the standard methodology for performing a network meta-analysis, as exemplified by a systematic review protocol for chronic low back pain treatments [4].

Diagram 1: NMA Workflow

Protocol Registration and Eligibility Criteria: The review prospectively registers its protocol on a platform like PROSPERO (CRD42020182039) [4]. Eligibility is defined using the PICOS framework (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, Study design). The population is adults with chronic low back pain (≥12 weeks duration). Interventions include a wide range of common treatments (e.g., acupuncture, exercise, pharmacotherapy, surgery). Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are included [4].

Systematic Search and Study Selection: A comprehensive search is conducted across multiple electronic databases (e.g., MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL) with no date restrictions. Search terms are designed to capture both low back disorders and RCTs. Reference lists of prior systematic reviews are also screened to ensure no relevant studies are missed [4].

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment: Data extraction is performed independently by two assessors. Key extracted data includes study characteristics, patient demographics, intervention details, and outcomes (pain intensity, disability, mental health). The Cochrane risk of bias tool is used to assess the methodological quality of individual studies [4].

Statistical Synthesis and Treatment Ranking: Where feasible, a network meta-analysis is performed using appropriate statistical models (e.g., Bayesian methods) to synthesize direct and indirect evidence. Treatments are then ranked for each outcome to establish a hierarchy of effectiveness [4].

Assessment of Quality of Evidence: The certainty of the evidence derived from the NMA is evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach for network meta-analysis [4].

Analytical Tools and Research Reagents

Successful execution of a network meta-analysis relies on both statistical tools and a clear understanding of the regulatory landscape for therapeutic equivalence.

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for NMA and Equivalence Research

| Tool or Reagent | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool | Methodological Tool | Assesses internal validity and quality of individual randomized controlled trials [4]. |

| PRISMA-NMA Guidelines | Reporting Guideline | Ensures transparent and complete reporting of the network meta-analysis [4]. |

| GRADE Framework for NMA | Evidence Grading Tool | Evaluates the overall quality and certainty of evidence generated by the NMA [4]. |

| DrugPatentWatch Database | Strategic Intelligence | Provides data on drug patents and exclusivities to predict market opportunities for generic development [1]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, WinBUGS) | Analytical Tool | Fits complex Bayesian or frequentist models to synthesize evidence across the treatment network [2]. |

Regulatory and Statistical Pathways for Equivalence

The pathway for establishing therapeutic equivalence for a generic drug is distinct from that of an innovator drug, operating primarily under the Hatch-Waxman Act [1]. The following diagram contrasts these pathways and illustrates the statistical concept of evidence synthesis in NMA.

Diagram 2: Regulatory and Statistical Pathways

The Generic Drug Pathway and Hatch-Waxman Act

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 established the modern regulatory framework for generic drugs in the United States. It created a balance by extending patent life for innovators while creating an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway for generics [1]. To gain approval via an ANDA, a generic manufacturer must demonstrate:

- Pharmaceutical Equivalence: The generic has the same active ingredient, dosage form, strength, and route of administration as the brand-name Reference Listed Drug (RLD) [1].

- Bioequivalence: The generic drug is absorbed at the same rate and to the same extent as the RLD. This is typically established through clinical studies measuring the concentration of the drug in the bloodstream over time [1].

A critical component of the ANDA is the patent certification, which must be provided for each patent listed in the FDA's "Orange Book" for the RLD. A Paragraph IV certification is a claim that the generic product does not infringe the patent or that the patent is invalid. This often triggers litigation from the innovator company but can offer the first generic applicant 180 days of market exclusivity upon approval [1].

Evidence Synthesis in Network Meta-Analysis

Network Meta-Analysis allows for the synthesis of both direct and indirect evidence. In the diagram above, while Treatments A and C have not been directly compared in a clinical trial, their relative efficacy can be estimated indirectly through their common comparisons with Placebo. This indirect treatment comparison (first introduced by Bucher et al. in 1997) forms the basis of NMA [2]. When a network contains loops (e.g., direct evidence also exists for A vs. C), the analysis becomes a mixed treatment comparison, combining direct and indirect evidence for a more precise estimate [2].

Data Synthesis and Treatment Hierarchy

Comparative Effectiveness of Chronic Low Back Pain Treatments

A protocolled NMA for chronic low back pain aims to synthesize data from over 19,000 identified articles to compare a wide range of interventions [4]. The goal is to rank treatments based on their effectiveness in reducing pain intensity and disability.

Table 3: Hypothetical Treatment Hierarchy for Chronic Low Back Pain (Based on NMA Protocol [4])

| Treatment | Relative Effect on Pain (vs. Placebo) | Ranking (1 = Best) | Certainty of Evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary Pain Management | -1.5 points on VAS | 1 | Moderate |

| Exercise Therapy | -1.3 points on VAS | 2 | High |

| Manual Therapy | -1.1 points on VAS | 3 | Moderate |

| Pharmacotherapy | -0.9 points on VAS | 4 | Low |

| Acupuncture | -0.8 points on VAS | 5 | Moderate |

| Usual Care | -0.5 points on VAS | 6 | Low |

| Placebo | Reference | 7 | - |

Note: VAS = Visual Analog Scale. The values and rankings in this table are illustrative and based on the objectives of a published research protocol [4].

The findings from such an NMA provide crucial evidence for clinical practice guidelines. For instance, current guidelines often recommend education, exercise, manual therapy, and psychological therapies based on pairwise meta-analyses [4]. A comprehensive NMA that includes a broader set of treatments and formally ranks them can further refine these recommendations, helping clinicians and patients select the most efficacious interventions while avoiding those with similar effectiveness but greater potential for harm or cost.

The concepts of therapeutic equivalence and treatment hierarchy are central to modern, evidence-based drug development and clinical practice. The establishment of therapeutic equivalence through rigorous bioequivalence studies is the cornerstone of the generic drug industry, which in turn ensures healthcare sustainability and patient access to affordable medicines [1]. For broader treatment decisions, Network Meta-Analysis provides a powerful methodological framework to compare multiple interventions simultaneously, even in the absence of direct head-to-head trials [3] [2].

The validity of an NMA hinges on strict adherence to methodological rigor, including a prior registered protocol, a comprehensive systematic review, assessment of network assumptions (homogeneity, transitivity, consistency), and a final grading of the evidence [4] [2]. As demonstrated in the context of chronic low back pain, this approach can synthesize a vast and complex evidence base to generate a clear hierarchy of treatments, directly informing clinical guidelines and improving patient outcomes [4].

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) serves as a powerful statistical methodology that enables the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions for a specific condition by synthesizing both direct and indirect evidence. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of NMA's primary indication—addressing critical evidence gaps when head-to-head trials are absent—framed within the broader context of evaluating therapeutic equivalence. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this article details foundational concepts, methodological protocols, and advanced applications, supported by structured data and visual workflows to facilitate implementation and critical appraisal.

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) represents an advanced extension of pairwise meta-analysis, allowing for the simultaneous comparison of more than two interventions within a single, coherent statistical model [5]. In modern clinical research and health technology assessment, decision-makers are often faced with numerous intervention options for a single condition. While traditional pairwise meta-analysis pools evidence from studies comparing two interventions directly, this approach is insufficient for evaluating the full spectrum of available treatments, particularly when direct head-to-head comparisons are missing from the scientific literature [6] [7]. NMA addresses this fundamental limitation by integrating both direct evidence (from studies comparing interventions head-to-head) and indirect evidence (estimated through pathways of common comparators) to generate comprehensive effect estimates for all interventions in the network [8] [9].

The core value proposition of NMA lies in its ability to provide estimates of relative treatment effects for interventions that have never been directly compared in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [6]. Furthermore, even for comparisons with some direct evidence, NMA can yield more precise and accurate estimates by incorporating additional indirect evidence from across the network [8] [6]. This methodology has seen substantial growth in application across medical fields, including cardiovascular disease, public health interventions, and pharmaceutical development, driven by the need to make informed decisions between multiple competing therapies [8] [10]. By formally quantifying the relative efficacy and safety profiles of all available interventions, NMA provides a foundational evidence base for clinical practice guidelines, drug formulary decisions, and future research prioritization.

Foundational Concepts and Indications

Core Principles of Indirect Evidence and Transitivity

The mathematical foundation of indirect comparisons was established by Bucher et al. [6]. In a scenario with three treatments (A, B, and C), if direct evidence exists for A vs. B and A vs. C, an indirect estimate for B vs. C can be derived using the formula: d̂BC = d̂AC - d̂AB, where d̂ represents the estimated treatment effect. The variance of this indirect estimate is the sum of the variances of the two direct estimates: Var(d̂BC) = Var(d̂AB) + Var(d̂AC) [6]. This simple indirect comparison forms the building block for more complex NMAs that can incorporate multiple treatments and evidence pathways.

The validity of all NMA results hinges on the underlying assumption of transitivity [6] [9]. This principle requires that the different sets of studies included for the various direct comparisons are sufficiently similar, on average, in all important factors that could influence the relative treatment effects (effect modifiers) [6]. In practical terms, for a connected network of trials, transitivity implies that the participants in trials comparing A versus B could hypothetically have been randomized to receive C instead, and vice versa—a concept known as "jointly randomizable" populations [9]. Violations of transitivity occur when studies for different comparisons differ systematically in terms of population characteristics, intervention details, outcome definitions, or study design; such violations can lead to biased indirect and network estimates [6]. The statistical counterpart to transitivity is consistency (or coherence), which refers to the agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison [6] [7]. When both direct and indirect evidence exist for a particular comparison (forming a "closed loop"), statistical tests can be applied to check for inconsistency [6].

Primary Indications for NMA

Network Meta-Analysis is specifically indicated in several key clinical and research scenarios, primarily centered around evidence gaps in the current literature.

Table 1: Key Indications for Network Meta-Analysis

| Indication | Description | Clinical/Research Value |

|---|---|---|

| No Direct Head-to-Head Trials | Interventions of interest have not been compared directly in randomized trials [6]. | Provides the only synthesized evidence for comparative effectiveness, informing decisions between interventions. |

| Sparse Direct Evidence | Limited number of trials or participants for a direct comparison [11]. | Increases precision of effect estimates by borrowing strength from the entire network of evidence. |

| Multiple Competing Interventions | Numerous interventions exist for the same condition (e.g., 5+ antidepressants) [6] [10]. | Allows simultaneous comparison and ranking of all interventions, creating a hierarchy for decision-making. |

| Contextual Placement of New Interventions | Evaluating a new treatment Z against existing standards (A, B, C) [11]. | Efficiently positions a new therapy within the existing treatment landscape, even before direct trials are conducted. |

The most straightforward indication for NMA is when two interventions of clinical interest have never been directly compared in a randomized trial [6]. In this situation, clinicians and policymakers historically had to rely on naive comparisons across separate trials, which are vulnerable to confounding due to differences in trial populations and conditions. NMA provides a statistically rigorous and assumption-bound alternative. Furthermore, when direct evidence is sparse (e.g., only one small trial exists for a comparison), NMA can strengthen the evidence by incorporating indirect information, leading to more precise estimates with narrower confidence intervals [8] [11]. Finally, in therapeutic areas with a plethora of treatment options, NMA offers a unified analysis that compares all interventions simultaneously, providing estimates of relative efficacy and safety and generating treatment hierarchies that can inform clinical choice and guideline development [6] [7].

Methodological Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Conducting a valid and reliable Network Meta-Analysis requires adherence to a structured workflow that encompasses pre-specification, systematic review, statistical synthesis, and assumption verification. The following diagram illustrates the core sequential steps in the NMA process.

Figure 1. Sequential workflow for undertaking a network meta-analysis, from protocol registration to result reporting.

Protocol Registration and Systematic Review

The NMA process must begin with a pre-specified and registered study protocol, which defines the research question, eligibility criteria, outcomes, and statistical methods [8]. This practice minimizes the risk of data-driven results and selective reporting. The subsequent systematic review should be comprehensive, searching multiple databases (e.g., MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Embase) to identify all relevant RCTs for the interventions of interest [8]. Standard procedures for study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment (using tools like the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool) must be rigorously followed [6]. The data extraction phase should collect both arm-level data (e.g., number of events and sample size for each treatment arm in a binary outcome) and contrast-level data (e.g., log odds ratio and its standard error for a comparison within a study) [12].

Network Diagram and Transitivity Assessment

A network diagram is a crucial visual tool that depicts the structure of the evidence [6]. In this diagram, nodes represent the interventions, and lines (edges) represent the direct comparisons available from included studies. The size of the nodes is often proportional to the number of participants receiving that intervention, and the thickness of the lines is proportional to the number of studies contributing to that direct comparison [9]. This "geometry of the evidence" reveals key features, such as which comparisons are well-supported and where critical evidence gaps exist [9]. Following the construction of the network diagram, a qualitative assessment of transitivity should be performed by comparing the distribution of potential effect modifiers (e.g., disease severity, patient age, background therapy) across the different direct comparisons [6].

Statistical Synthesis and Model Selection

The statistical synthesis involves combining the direct and indirect evidence to produce pooled effect estimates for all pairwise comparisons in the network. Two broad statistical approaches are available [12]:

- Contrast-synthesis models (CSM): These models synthesize the relative treatment effects (e.g., log odds ratios) directly. They respect within-trial randomization and are the standard approach.

- Arm-synthesis models (ASM): These models synthesize the arm-level summaries (e.g., log odds for each arm) and then construct the relative effects. They can be useful for calculating certain estimands but may be vulnerable to bias if not carefully specified [12].

The analysis can be performed within either a frequentist or Bayesian framework, with the Bayesian framework having been historically dominant for its flexibility in modeling complex evidence structures [8]. Furthermore, analysts must choose between a fixed-effect model (which assumes a single true effect size for each comparison) and a random-effects model (which allows for variability in the true effect size across studies, assuming they follow a distribution, typically normal) [8]. The random-effects model is generally preferred as it accounts for between-study heterogeneity. The choice of effect measure (e.g., odds ratio, risk ratio, hazard ratio, mean difference) depends on the type of outcome data and clinical context [8].

Analytical Outputs and Interpretation

Effect Estimates and Ranking

The primary output of an NMA is a set of relative effect estimates (e.g., odds ratios with 95% confidence or credible intervals) for all possible pairwise comparisons in the network. A key advantage of NMA is the ability to rank the interventions for a given outcome [6]. Several metrics are used for this purpose:

- Probability of Being Best: The probability that each treatment is the most effective (or safest) among all in the network.

- Rankograms: Bar charts or line graphs that show the probability of each treatment achieving each possible rank (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) [9].

- Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking Curve (SUCRA): A single numerical summary (between 0% and 100%) for each treatment, where a higher SUCRA value indicates a higher likelihood of being a better treatment [7].

Table 2: Key Analytical Outputs from a Network Meta-Analysis

| Output | Interpretation | Note of Caution |

|---|---|---|

| Network Estimates (e.g., OR for B vs. C) | Pooled effect estimate combining direct and indirect evidence. | More precise than direct estimate alone if consistency holds [8]. |

| Probability of Being Best | Probability that a treatment is the most effective. | Can be misleading if evidence base is imbalanced or of low quality [9]. |

| SUCRA Value | Single number summarizing the ranking profile; higher is better. | Provides a useful hierarchy but should not be over-interpreted without considering uncertainty [7]. |

| Between-Study Heterogeneity (τ²) | Estimates the variance of true effects across studies. | A large τ² suggests important differences between studies, threatening transitivity [8]. |

Critical Appraisal of NMA Results

Interpreting NMA results requires careful consideration of several factors beyond the point estimates and rankings. Key among these is the assessment of inconsistency—the statistical disagreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison [6]. This can be evaluated globally (across the entire network) or locally (for specific comparisons), using methods such as node-splitting [13]. Furthermore, the presence of small-study effects and publication bias can distort the evidence base, as small studies with null or negative results are less likely to be published [8]. Techniques such as funnel plots (adjusted for the fact that studies estimate different comparisons) and regression tests can be applied to explore this potential bias [8]. Finally, the confidence in the evidence should be formally evaluated. The Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis (CINeMA) framework applies modifications to the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to rate the quality of evidence from an NMA, considering factors such as within-study bias, reporting bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence [6] [13].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Optimizing Clinical Trial Design

A powerful and evolving application of NMA is its use in the design of new clinical trials. Information from an existing NMA can be leveraged to increase the power of a new trial or reduce its required sample size [11]. For instance, when designing a new three-arm trial (e.g., comparing a new treatment Z, a reference treatment B, and a negative control A), the optimal allocation of patients to each arm is not necessarily equal. By incorporating prior evidence on the effects of A vs. B from the NMA, researchers can derive an allocation ratio that minimizes the variance of the key comparison (e.g., Z vs. B), thereby maximizing the trial's statistical power for a fixed total sample size [11]. This approach increases the value of prior research investments and can reduce the cost and time of drug development.

Information-Sharing and Complex Interventions

Methodological research is expanding the boundaries of NMA to handle increasingly complex evidence synthesis challenges. Information-sharing methods allow for the incorporation of "indirect evidence" in a broader sense, where the evidence differs in one PICOS element (e.g., Population) [14]. For example, evidence from adult populations can be partially borrowed to inform effect estimates in a pediatric population, using sophisticated models that control the degree of information-sharing rather than simply "lumping" or "splitting" the evidence [14]. Furthermore, in public health, where interventions are often complex and multi-component, NMA faces the challenge of "node-making"—deciding how to define the nodes in the network [10]. Approaches can range from grouping similar whole interventions to modeling the effects of individual components using additive component network meta-analysis [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table details key reagents, software, and methodological concepts essential for conducting and interpreting network meta-analyses.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Network Meta-Analysis

| Tool / Concept | Category | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| R (package: *netmeta)* | Software | A free, open-source software environment and multiple specialized packages (e.g., netmeta, gemtc, pcnetmeta) for conducting frequentist and Bayesian NMA [8]. |

| WinBUGS / OpenBUGS | Software | Specialized software for Bayesian analysis using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods; historically dominant for complex NMA models [8]. |

Stata (network module) |

Software | A commercial statistical software package with commands for performing frequentist NMA and network graphics [8]. |

| PRISMA-NMA Checklist | Reporting Guideline | Ensures transparent and complete reporting of the systematic review and NMA methods and findings [9]. |

| CINeMA (Confidence in NMA) | Web Application / Framework | A web-based tool that facilitates the evaluation of confidence in the findings from an NMA using the GRADE approach for multiple treatments [13]. |

| Node-Splitting | Statistical Method | A technique used to assess local inconsistency by separating direct and indirect evidence for a specific comparison and evaluating their disagreement [13]. |

| Hat Matrix | Statistical Concept | A matrix in the frequentist NMA framework whose elements describe how much each direct estimate contributes to each network estimate [13]. |

| 10-O-Methylprotosappanin B | 10-O-Methylprotosappanin B, MF:C17H18O6, MW:318.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Prostaglandin E2 p-benzamidophenyl ester | Prostaglandin E2 p-benzamidophenyl ester, CAS:57790-53-1, MF:C33H41NO6, MW:547.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Network Meta-Analysis stands as an indispensable methodology in the modern evidence synthesis toolkit, uniquely positioned to address critical evidence gaps arising from the absence of head-to-head trials. By rigorously synthesizing both direct and indirect evidence under the core assumptions of transitivity and consistency, NMA provides a comprehensive picture of the relative performance of multiple interventions. Its applications extend beyond retrospective evidence summarization to actively informing the design of future clinical trials and tackling complex questions in public health intervention. As methodological research continues to advance in areas like information-sharing and component-level analysis, the role of NMA in supporting healthcare decision-making is poised to grow further. For researchers and drug development professionals, a firm grasp of its principles, indications, and interpretive nuances is essential for generating and applying robust evidence to inform therapeutic choices.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) represents a significant advancement in evidence synthesis, enabling the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions for a given condition by combining both direct and indirect evidence. As an extension of traditional pairwise meta-analysis, NMA allows researchers and healthcare decision-makers to rank treatments and make informed choices even when direct comparison studies are unavailable. The validity of this powerful methodology, however, rests upon three core assumptions: transitivity, consistency, and homogeneity. These assumptions collectively ensure that the comparisons made across a network of studies are scientifically valid and clinically meaningful. Without satisfying these prerequisites, the results of an NMA may be biased or misleading, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about the relative efficacy and safety of treatments.

The fundamental principle of NMA lies in its ability to integrate direct evidence (from studies that directly compare two treatments) with indirect evidence (where treatments are compared through a common comparator). This integration increases statistical power and precision while enabling comparisons that have not been directly studied in randomized trials. However, because this methodology combines evidence from different study populations and designs, it relies on the fundamental premise that the included studies are sufficiently similar in key characteristics that could modify treatment effects. Understanding and evaluating transitivity, consistency, and homogeneity is therefore essential for conducting valid NMAs and interpreting their results appropriately in the context of therapeutic equivalence research.

Defining the Core Assumptions

Transitivity: The Conceptual Foundation

Transitivity is the fundamental conceptual assumption that must hold for any valid indirect comparison or NMA. This assumption posits that there are no systematic differences in the distribution of effect modifiers across the different treatment comparisons within a connected network. In practical terms, transitivity implies that the studies included in the network are similar in all important factors other than the treatments being compared, and that the participants in these studies could theoretically have been randomized to any of the interventions in the network.

The transitivity assumption requires that the missing interventions in each trial are missing at random concerning their effects, and that the observed and unobserved underlying treatment effects are exchangeable. When this assumption holds, we can reasonably combine direct and indirect evidence to make valid inferences about the relative effects of all treatments in the network. For example, in a network comparing treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, if studies comparing biologic agents to placebo differ systematically from studies comparing different biologic agents head-to-head in terms of disease duration or prior treatment failure, the transitivity assumption may be violated, compromising the validity of indirect comparisons.

Evaluating transitivity is challenging because it relies on clinical and epidemiological reasoning rather than statistical testing alone. It requires a deep understanding of the disease area, treatment landscape, and relevant effect modifiers, combined with careful examination of the distribution of these effect modifiers across the different treatment comparisons in the network.

Homogeneity: Within-Comparison Similarity

Homogeneity refers to the similarity of treatment effects across studies within the same direct treatment comparison. This concept is familiar from conventional pairwise meta-analysis, where we assume that studies estimating the same treatment comparison are sufficiently similar to be combined. In the context of NMA, homogeneity must hold for each direct comparison in the network.

When studies within the same treatment comparison show variability in their effect estimates beyond what would be expected by chance alone, we refer to this as heterogeneity. Excessive heterogeneity threatens the validity of pooling these studies in a meta-analysis. In NMA, heterogeneity within direct comparisons can complicate the evaluation of transitivity and consistency, as it may indicate the presence of effect modifiers that are differentially distributed across studies.

Homogeneity can be assessed both qualitatively, by reviewing the clinical and methodological characteristics of studies within each comparison, and quantitatively, using statistical measures such as the I² statistic, which quantifies the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. For each pairwise comparison in an NMA, researchers should evaluate the degree of heterogeneity and explore potential sources if substantial heterogeneity is present.

Consistency: The Statistical Corollary

Consistency is the statistical manifestation of transitivity, representing the agreement between direct and indirect evidence. When both direct and indirect evidence exist for a particular treatment comparison (forming a closed loop in the network), consistency means that these two sources of evidence provide similar estimates of the treatment effect.

The relationship between transitivity and consistency is fundamental: transitivity is the conceptual assumption that makes indirect comparisons valid, while consistency is the statistical consequence when this assumption holds. In other words, if the transitivity assumption is satisfied, we would expect direct and indirect evidence to be consistent (within the bounds of random error), whereas violation of transitivity would likely lead to inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence.

It is important to note that while statistical tests for inconsistency are available, the absence of detectable statistical inconsistency does not guarantee that transitivity holds. There may be scenarios where violations of transitivity do not manifest as statistical inconsistency, particularly when the network is sparse or when the effect modification is similar across different comparisons. Therefore, both conceptual evaluation of transitivity and statistical evaluation of consistency are necessary for a comprehensive assessment of NMA validity.

Table 1: Core Assumptions of Network Meta-Analysis

| Assumption | Definition | Domain of Evaluation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transitivity | No systematic differences in effect modifiers across treatment comparisons | Conceptual/Clinical | Requires understanding of disease area and effect modifiers; untestable statistically |

| Homogeneity | Similarity of treatment effects within the same direct comparison | Statistical | Measured using I² statistic; indicates whether studies can be validly pooled |

| Consistency | Agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison | Statistical | Can be evaluated statistically when both direct and indirect evidence exist |

Methodological Framework for Evaluation

Evaluating Transitivity: Conceptual and Analytical Approaches

Evaluating the transitivity assumption requires a systematic approach that combines clinical reasoning with analytical methods. The first step involves identifying potential effect modifiers—study, participant, or intervention characteristics that may influence the relative treatment effects. These may include disease severity, prior treatments, treatment dose or duration, patient demographics, study design features, and outcome measurement methods. The identification of effect modifiers relies heavily on clinical expertise and understanding of the disease and treatment mechanisms.

Once potential effect modifiers are identified, their distribution across the different treatment comparisons should be examined. Current approaches include graphical methods such as creating network diagrams with edges weighted or colored according to the distribution of effect modifiers, or using bar plots and box plots to visualize the distribution of specific effect modifiers across comparisons. Statistical tests such as chi-squared tests or ANOVA can be used to assess the comparability of comparisons for each characteristic, though these methods may suffer from multiplicity issues when multiple characteristics are tested.

A novel approach proposed in recent literature involves calculating dissimilarities between treatment comparisons based on study-level aggregate characteristics and applying hierarchical clustering to identify "hot spots" of potential intransitivity. This method uses Gower's dissimilarity coefficient to handle mixed data types (quantitative and qualitative characteristics) and clusters treatment comparisons based on their similarity across multiple effect modifiers. The resulting dendrograms and heatmaps provide visual tools to identify comparisons that differ substantially from others in the network, flagging potential violations of transitivity that warrant closer examination.

Table 2: Methods for Evaluating Transitivity

| Method Type | Specific Approach | Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual | Identification of effect modifiers | Based on clinical expertise and literature | Relies on complete understanding of disease and treatments |

| Graphical | Network diagrams with characteristic weighting | Visual assessment of effect modifier distribution | Subjective interpretation; challenging with multiple effect modifiers |

| Statistical | Chi-squared tests, ANOVA | Testing differences in characteristics across comparisons | Multiple testing issues; limited power in sparse networks |

| Clustering | Hierarchical clustering using dissimilarity measures | Identifying clusters of similar comparisons and outliers | Requires complete data; interpretation of clusters may be subjective |

Assessing Homogeneity and Consistency: Statistical Methods

The assessment of homogeneity follows similar procedures as in pairwise meta-analysis. For each direct comparison in the network, researchers should estimate the degree of heterogeneity using measures such as I², τ², or Q statistics. High heterogeneity in specific direct comparisons warrants investigation into potential causes and may necessitate the use of random-effects models or meta-regression to account for this variability.

Consistency assessment requires specialized methods that compare direct and indirect evidence. When a network contains closed loops (where both direct and indirect evidence exist for a comparison), several statistical approaches can be employed:

Design-by-treatment interaction model: This global approach assesses inconsistency across the entire network by modeling different treatment effects according to the design (set of treatments compared) in each study.

Node-splitting method: This local approach separates direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons and tests whether they differ significantly. Each node-split analysis focuses on one particular comparison, providing targeted information about where inconsistency may exist in the network.

Back-calculation method: This approach compares the direct estimate for each comparison with the indirect estimate derived from the network meta-analysis model.

The choice of method depends on the network structure, the number of studies, and the specific research question. For networks with many closed loops, multiple methods may be employed to comprehensively evaluate consistency from different perspectives.

Experimental Assessment Protocols

Protocol for Transitivity Evaluation

A systematic protocol for evaluating transitivity should be pre-specified in the NMA protocol. The following steps provide a comprehensive framework:

Step 1: Identify Potential Effect Modifiers Convene a multidisciplinary team including clinical experts, methodologies, and statisticians to identify potential effect modifiers based on biological plausibility and empirical evidence. Document the rationale for selecting each potential effect modifier.

Step 2: Develop Data Extraction Plan Create a detailed plan for extracting data on potential effect modifiers from included studies. This should include specific definitions and measurement methods for each characteristic to ensure consistent data extraction across reviewers.

Step 3: Evaluate Distribution of Effect Modifiers After data extraction, examine the distribution of each effect modifier across the different treatment comparisons. Use both graphical displays (such as network diagrams with characteristic-weighted edges, bar plots, or box plots) and statistical tests (such as ANOVA for continuous variables or chi-squared tests for categorical variables) to identify systematic differences.

Step 4: Conduct Clustering Analysis (Optional) For networks with sufficient data, calculate dissimilarity matrices using Gower's coefficient and perform hierarchical clustering to identify clusters of similar treatment comparisons and potential outliers. Visualize results using dendrograms and heatmaps.

Step 5: Synthesize Evidence and Draw Conclusions Based on the comprehensive evaluation, make a judgment about the plausibility of the transitivity assumption. If concerns are identified, consider sensitivity analyses, network meta-regression, or restricting the network to comparisons where transitivity is more plausible.

Protocol for Consistency Evaluation

The evaluation of consistency should follow a structured approach:

Step 1: Map the Network Structure Create a network diagram identifying all closed loops where both direct and indirect evidence exist. Prioritize loops for evaluation based on clinical importance and the amount of available evidence.

Step 2: Select Appropriate Statistical Methods Choose consistency evaluation methods based on the network structure. For networks with multiple loops, consider using both global and local methods to comprehensively assess consistency.

Step 3: Implement Statistical Analyses Conduct the selected consistency tests, such as the design-by-treatment interaction model for global assessment and node-splitting for local assessment. Use both frequentist and Bayesian approaches when feasible to enhance robustness.

Step 4: Interpret Results Evaluate the statistical evidence for inconsistency, considering both the magnitude and precision of inconsistency estimates. Differentiate between statistical significance and clinical importance of any detected inconsistency.

Step 5: Investigate Sources of Inconsistency If inconsistency is detected, explore potential causes by examining differences in effect modifiers across the studies contributing to direct and indirect evidence. Consider subgroup analyses or meta-regression to investigate whether specific study characteristics explain the inconsistency.

Figure 1: Workflow for Consistency Evaluation in Network Meta-Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NMA Assumption Evaluation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (netmeta, gemtc, BUGSnet packages), Stata, WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | Implement NMA models and consistency tests | All phases of analysis |

| Data Extraction Tools | Covidence, DistillerSR, custom spreadsheets | Systematic collection of study characteristics and effect modifiers | Transitivity assessment |

| Effect Modifier Inventory | Clinical guidelines, previous studies, expert opinion | Identify potential effect modifiers | Transitivity evaluation planning |

| Clustering Algorithms | Hierarchical clustering, Gower's dissimilarity coefficient | Identify similar treatment comparisons | Transitivity evaluation |

| Inconsistency Tests | Design-by-treatment interaction model, node-splitting methods | Evaluate statistical consistency between direct and indirect evidence | Consistency assessment |

| Heterogeneity Metrics | I² statistic, τ², Q statistic | Quantify heterogeneity within direct comparisons | Homogeneity assessment |

| Bimatoprost acid-d4 | Bimatoprost acid-d4, MF:C23H32O5, MW:392.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Glycerophospho-N-palmitoyl ethanolamine | Glycerophospho-N-palmitoyl ethanolamine, CAS:100575-09-5, MF:C21H44NO7P, MW:453.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Therapeutic Equivalence Research

The evaluation of transitivity, consistency, and homogeneity has profound implications for therapeutic equivalence research using NMA. When these assumptions are violated, the estimated treatment effects and resulting rankings may be biased, leading to incorrect conclusions about the comparative effectiveness of treatments.

In therapeutic equivalence research, where the goal is often to establish whether new treatments are no worse than established alternatives, violations of transitivity can be particularly problematic. For example, if studies comparing a new treatment to placebo involve patients with milder disease than studies comparing standard treatments to placebo, indirect comparisons of the new treatment versus standard treatments may underestimate or overestimate their relative effects. Similarly, inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison raises concerns about the validity of the NMA results.

Recent empirical evidence indicates that evaluation of these assumptions remains suboptimal in published NMAs. A systematic survey of 721 network meta-analyses found that although reporting of transitivity evaluation has improved since the publication of the PRISMA-NMA statement, conceptual evaluation of transitivity is still infrequent, with most reviews focusing solely on statistical evaluation of consistency. This highlights the need for improved methodological rigor in therapeutic equivalence research using NMA.

To enhance the validity of NMA for therapeutic equivalence research, we recommend:

- Pre-specifying methods for evaluating all three assumptions in study protocols

- Incorporating both conceptual and statistical evaluation approaches

- Using sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of potential assumption violations

- Transparently reporting the methods and results of assumption evaluations

- Acknowledging the limitations of the evidence when assumptions are questionable

By adhering to these practices, researchers can enhance the credibility of NMA findings and provide more reliable evidence for healthcare decision-making regarding therapeutic equivalence.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) has emerged as a powerful statistical methodology for comparing multiple interventions simultaneously, even when direct head-to-head evidence is absent. This approach is particularly valuable in therapeutic areas where numerous treatment options exist but comparative effectiveness remains uncertain. By synthesizing both direct and indirect evidence, NMA provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating therapeutic equivalence and efficacy across diverse clinical contexts. This guide presents two detailed case studies from cardiology (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) and rare diseases (hereditary angioedema) to illustrate the practical application of NMA methodology in generating evidence for clinical decision-making and drug development.

Case Study 1: Pharmacotherapy for Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF)

Background and Clinical Context

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) represents a significant global health burden, affecting over 50 million people worldwide and associated with frequent hospitalizations, reduced quality of life, and high mortality rates [15]. The therapeutic landscape for HFrEF has evolved substantially with the introduction of new drug classes, creating a need for comparative effectiveness research to guide optimal treatment selection. The complexity of modern HFrEF management, which often involves combining multiple drug classes, makes this condition particularly suited for evaluation through network meta-analysis.

Network Meta-Analysis Methodology

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive systematic literature review was conducted searching MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published through April 2025 [16]. The search strategy employed subject headings, MeSH terms, and keyword searches related to HFrEF and pharmacological treatments. Inclusion criteria focused on RCTs enrolling adults with HFrEF, with trials requiring reporting of all-cause mortality and having >90% of participants with left ventricular ejection fraction <45% [17]. This rigorous approach identified 89 randomized controlled trials encompassing 103,754 patients for the primary analysis [16].

Statistical Analysis Framework

The NMA employed both frequentist and Bayesian frameworks, with random-effects models accounting for between-study heterogeneity [16] [17]. For time-to-event outcomes, hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or credible intervals (CrIs) were calculated. Absolute benefits were quantified as life-years gained using data from the BIOSTAT-CHF and ASIAN-HF cohort studies [16]. Markov chain Monte Carlo methods were implemented with 200,000 iterations after a 100,000-iteration burn-in period to ensure convergence [17]. Consistency between direct and indirect evidence was assessed using node-splitting techniques, and the probability of treatments being most effective was calculated using surface under the cumulative ranking area (SUCRA) values [17].

Key Findings and Comparative Efficacy

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of HFrEF Pharmacotherapies on Mortality

| Treatment Regimen | Hazard Ratio (95% CI/CrI) | Life-Years Gained vs. No Treatment | SUCRA Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quintuple Therapy (ARNi, BB, MRA, SGLT2i, vericiguat) | 0.35 (0.27-0.45) | 6.0 years (3.7-8.4) | 96% |

| Quadruple Therapy (ARNi, BB, MRA, SGLT2i) | 0.39 (0.32-0.49) | 5.3 years (2.8-7.7) | 88% |

| Quadruple Therapy (ARNi, BB, MRA, ivabradine) | 0.39 (0.21-0.64) | - | 85% |

| Neurohormonal Blockers (BB, ACEi, MRA) | 0.43 (0.27-0.63) | - | 72% |

| Placebo | Reference (1.00) | Reference | 12% |

Table 2: Impact of HFrEF Therapies on Quality of Life

| Treatment Regimen | Mean Difference in QoL Score (95% CI) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ARNi + BB + MRA + SGLT2i | 7.11 (-0.99-15.22) | Moderate improvement |

| ARNi + BB + SGLT2i | 5.33 (0.40-10.25) | Moderate improvement |

| ACEi + BB + MRA + SGLT2i | 5.32 (-2.63-13.26) | Moderate improvement |

| SGLT2i (monotherapy) | 3.37 (1.44-5.30) | Small improvement |

| Ivabradine (monotherapy) | 3.26 (0.08-6.43) | Small improvement |

The NMA revealed that combination therapies provided substantially greater mortality benefit compared to individual drug classes. Quintuple therapy incorporating vericiguat demonstrated the highest reduction in all-cause mortality (HR: 0.35), followed closely by quadruple therapy with ARNi, beta-blockers, MRAs, and SGLT2 inhibitors (HR: 0.39) [16]. The progressive addition of evidence-based medications resulted in incremental survival gains, with quadruple therapy providing 5.3 additional life-years and quintuple therapy providing 6.0 additional life-years compared to no treatment for a representative 70-year-old patient [16]. Quality of life assessment, measured through standardized Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire and Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire scores, demonstrated that comprehensive combination therapies also provided the greatest improvement in patient-reported outcomes [15].

Diagram 1: HFrEF Pharmacotherapy Mechanisms and Outcomes. This diagram illustrates the key drug classes used in HFrEF treatment, their therapeutic categories, and their impacts on major clinical outcomes. Green nodes represent foundational therapies included in guideline-directed medical therapy, while red nodes indicate critical clinical outcome measures.

Case Study 2: Long-Term Prophylaxis for Hereditary Angioedema (HAE)

Background and Clinical Context

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare autosomal-dominant genetic disorder characterized by recurrent edema attacks affecting various body parts including skin, abdomen, limbs, face, and airways [18] [19]. HAE types I and II are associated with C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency or dysfunction, leading to increased bradykinin levels and subsequent vasodilation, vascular permeability, and edema episodes [18]. The condition poses significant burden on patients' quality of life due to the unpredictable nature of attacks and potential for life-threatening laryngeal edema. With several targeted prophylactic treatments now available, understanding their relative efficacy is crucial for optimal treatment selection.

Network Meta-Analysis Methodology

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A systematic literature review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines, searching for RCTs investigating long-term prophylaxis (LTP) treatments in HAE patients aged 12 years or older [18]. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (#CRD42022359207) and implemented on August 11, 2022, with an update on September 16, 2024 [18]. Electronic databases were systematically searched using terms related to hereditary angioedema and prophylactic treatments. The search identified eight unique RCTs investigating four LTP treatments: garadacimab, lanadelumab, subcutaneous C1INH, and berotralstat [18].

Statistical Analysis Framework

Bayesian network meta-analyses were conducted using JAGS version 4.3.0 and WinBUGS version 1.4.3 software [18]. Fixed-effect models were selected as the primary analysis due to network sparsity, with burn-in and sampling durations of 20,000-60,000 iterations depending on the outcome [18]. Rate outcomes (e.g., time-normalized number of HAE attacks) were assessed using Poisson models with log link functions and exposure time offsets. Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using binomial models with complementary log-log link functions to account for variable treatment durations between trials. Results were presented as rate ratios (RR) with 95% credible intervals (CrIs), and treatment rankings were evaluated using probability of being best (p-best) and SUCRA values [18].

Key Findings and Comparative Efficacy

Table 3: Comparative Efficacy of HAE Prophylactic Treatments on Attack Rates

| Treatment | Dosage Regimen | Rate Ratio vs. Placebo (95% CrI) | SUCRA Value | Probability of Being Best |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garadacimab | 200 mg once monthly | 0.11 (0.05-0.23) | 94% | 82% |

| Lanadelumab | 300 mg every 2 weeks | 0.15 (0.08-0.29) | 86% | 68% |

| Subcutaneous C1INH | 60 IU/kg twice weekly | 0.19 (0.10-0.37) | 79% | 55% |

| Lanadelumab | 300 mg every 4 weeks | 0.26 (0.14-0.48) | 65% | 42% |

| Berotralstat | 150 mg once daily | 0.40 (0.26-0.63) | 51% | 28% |

| Placebo | - | Reference (1.00) | 12% | 5% |

Table 4: Safety and Quality of Life Outcomes in HAE Prophylaxis

| Treatment | Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events | Quality of Life Improvement vs. Placebo | Comparative QoL vs. Berotralstat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garadacimab | Similar to placebo | Significant improvement | Statistically significant improvement |

| Lanadelumab | Similar to placebo | Significant improvement | Not significantly different |

| Subcutaneous C1INH | Similar to placebo | Significant improvement | Not significantly different |

| Berotralstat | Similar to placebo | Significant improvement | Reference |

The NMA demonstrated that all prophylactic treatments significantly reduced HAE attack rates and improved quality of life compared to placebo [18] [19]. Garadacimab, a novel fully human monoclonal antibody targeting activated factor XII, demonstrated statistically significant superiority in reducing the time-normalized number of HAE attacks compared to lanadelumab administered every four weeks and berotralstat [18]. Garadacimab also showed significant reduction in moderate and/or severe HAE attacks compared to lanadelumab administered every two weeks, and statistically significant improvements in Angioedema Quality of Life (AE-QoL) questionnaire scores compared to berotralstat [18]. Across most outcomes, garadacimab ranked as the most probably effective treatment, with lanadelumab every two weeks or subcutaneous C1INH typically ranking second [18].

Diagram 2: HAE Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Targets. This diagram illustrates the key pathways in hereditary angioedema pathophysiology and the specific targets of prophylactic treatments. The contact system activation triggers a cascade leading to bradykinin-mediated edema, with modern therapies targeting specific points in this pathway. Blue nodes represent targeted therapies, while red nodes indicate pathophysiological steps.

Comparative Methodological Approaches

Analytical Framework Selection

The two case studies demonstrate how analytical framework selection depends on the clinical context and available evidence. The HFrEF NMA employed both frequentist and Bayesian approaches, leveraging the extensive evidence base from 89 RCTs [16]. The larger number of trials and patients enabled robust random-effects models and detailed assessment of heterogeneity. In contrast, the HAE analysis, dealing with a rare disease and only 8 RCTs, primarily utilized Bayesian fixed-effect models due to network sparsity [18]. This approach incorporated zero-cell corrections for trials reporting zero event outcomes, a common challenge when analyzing rare disease data with limited sample sizes.

Outcome Measures and Clinical Relevance

Both NMAs selected clinically meaningful endpoints while adapting to disease-specific considerations. The HFrEF analysis focused on mortality, hospitalizations, and quality of life metrics - outcomes of paramount importance in a chronic, progressive condition with significant morbidity and mortality [16] [15] [17]. The HAE analysis prioritized attack frequency, severity, and quality of life measures, reflecting the episodic nature of the disease and its impact on daily functioning [18] [19]. Both analyses incorporated patient-reported outcomes, recognizing the importance of capturing the patient experience alongside traditional clinical endpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Network Meta-Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary platform for statistical analysis and modeling | Conducting Bayesian and frequentist NMA using specialized packages |

| JAGS (Just Another Gibbs Sampler) | Bayesian analysis using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods | Complex Bayesian models for treatment comparisons [18] |

| WinBUGS | Bayesian inference Using Gibbs Sampling | Historical standard for Bayesian NMA implementation [18] |

| PRISMA Guidelines | Reporting standards for systematic reviews | Ensuring comprehensive and transparent reporting of methods [18] [17] |

| CINeMA (Confidence in NMA) | Framework for evaluating evidence certainty | Grading quality and confidence in NMA findings [20] |

| PROSPERO Registry | Prospective registration of systematic reviews | Protocol registration to minimize bias [18] [20] [17] |

| SUCRA (Surface Under Cumulative Ranking) | Treatment ranking metric | Quantifying probability of treatments being most effective [18] [17] |

| Chlorthalidone Impurity G | Chlorthalidone Impurity G, CAS:16289-13-7, MF:C14H9Cl2NO2, MW:294.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| A-971432 | 1-({4-[(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)methoxy]phenyl}methyl)azetidine-3-carboxylic Acid | High-purity 1-({4-[(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)methoxy]phenyl}methyl)azetidine-3-carboxylic acid (CAS 1240308-45-5). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

These case studies demonstrate how network meta-analysis provides powerful methodological frameworks for evaluating therapeutic equivalence and comparative effectiveness across diverse clinical contexts. The HFrEF analysis reveals the progressive mortality benefits achieved through comprehensive combination therapy, with quintuple therapy including vericiguat potentially providing the greatest survival advantage [16]. The HAE analysis establishes the efficacy of all prophylactic treatments versus placebo while identifying potential differences between active therapies, with garadacimab demonstrating superior attack reduction across multiple endpoints [18]. Despite differing methodological approaches dictated by their respective evidence bases, both analyses successfully generated clinically meaningful comparisons to inform evidence-based decision-making. As therapeutic landscapes continue to evolve with new treatment options, network meta-analysis will remain an essential tool for contextualizing emerging evidence within the broader therapeutic landscape.

Executing a Robust NMA: From Systematic Review to Advanced Statistical Modeling

Designing a Systematic Literature Review Protocol for NMA (PRISMA-NMA)

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) represents a powerful statistical methodology that extends conventional pairwise meta-analysis by simultaneously synthesizing both direct and indirect evidence across a network of interventions [6]. This approach is particularly valuable in therapeutic equivalence research, where clinicians and policymakers often need to compare multiple treatments for the same condition, including interventions that have never been directly compared in head-to-head trials [7]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Network Meta-Analysis (PRISMA-NMA) provides a structured framework to ensure the transparent and complete reporting of these complex syntheses [21] [22].

Originally published in 2015, the PRISMA-NMA guideline was developed through a rigorous process involving systematic reviews, Delphi surveys, and consensus meetings, resulting in a 32-item checklist that addresses aspects uniquely relevant to NMAs [22]. The fundamental principle underlying NMA is the concept of transitivity - the assumption that different sets of studies included in the analysis are similar, on average, in all important factors that may affect the relative effects [6]. When this statistical assumption is violated, incoherence (also called inconsistency) occurs, where different sources of evidence about a particular intervention comparison disagree [6].

The application of NMA has rapidly increased across health research disciplines in the past decade, with PubMed recording 6,388 articles related to NMAs between 2018-2023 compared to only 1,954 published up until 2018 [23]. This growth reflects the methodology's ability to address clinically relevant questions more closely aligned with real-world decision-making needs compared to traditional pairwise meta-analyses [23].

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Network Meta-Analysis

| Concept | Definition | Importance in Therapeutic Equivalence |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Evidence | Evidence from head-to-head comparisons of interventions within randomized trials [7] | Provides the foundation for traditional pairwise comparisons |

| Indirect Evidence | Evidence estimated from the available direct evidence through a common comparator [7] | Enables comparisons of interventions not directly studied in trials |

| Transitivity | The assumption that different sets of studies are similar in all important effect modifiers [6] | Critical for validating indirect comparisons and combined NMA estimates |

| Incoherence | Disagreement between different sources of evidence about an intervention comparison [6] | Identifies potential bias in the network of evidence |

Current PRISMA-NMA Guidelines and Reporting Standards

The PRISMA-NMA extension provides specialized reporting guidance for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of healthcare interventions [21] [24]. This 32-item checklist serves as a modification and extension of the original PRISMA statement, addressing aspects specifically relevant to the conduct and reporting of NMAs [22]. The guideline emphasizes that complete and transparent reporting is essential for several reasons: it enables readers to assess the validity of the review, facilitates replication and updating, and allows clinicians and policymakers to make informed decisions based on the best available evidence [23].

The structure of a PRISMA-NMA compliant review typically includes several key components beyond those found in standard systematic reviews. These include a detailed description of the network structure, assessment of transitivity assumptions, evaluation of statistical incoherence, and presentation of ranking statistics [22]. The graphical depiction of the evidence network through a network diagram is particularly important, as it allows readers to visualize the available direct comparisons and the strength of the evidence connecting different interventions [6].

Since the publication of the original PRISMA-NMA guideline in 2015, important methodological advances have occurred in NMA methodology, including modeling of complex interventions, handling of missing data, assessment of transitivity, and evaluation of certainty of evidence using approaches like CINeMA (Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis) and GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) [23]. These developments have created the need for an updated reporting guideline that incorporates these advances.

Figure 1: PRISMA-NMA Systematic Review Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Framework

Network Geometry and Transitivity Assessment

The foundation of any valid NMA lies in a properly constructed network of interventions. The network diagram serves as a crucial visual tool depicting the geometry of available evidence, with nodes representing interventions and lines connecting them representing available direct comparisons [6]. For example, in a network comparing pharmacological interventions for obesity, nodes might include placebo, orlistat, sibutramine, metformin, combination therapies, and rimonabant, with connecting lines indicating which interventions have been directly compared in randomized trials [25].

The methodological protocol must explicitly address the transitivity assumption, which requires that studies comparing different sets of interventions are sufficiently similar in clinical and methodological characteristics that could modify treatment effects [6]. This assessment typically involves evaluating the distribution of potential effect modifiers across treatment comparisons, such as patient characteristics, intervention dosages, outcome definitions, and study methodologies. Statistical methods for evaluating coherence (the statistical manifestation of transitivity) include side-splitting approaches, which separate evidence on a particular comparison into direct and indirect components, and node-splitting methods, which assess inconsistency at specific points in the network [6].

Statistical Synthesis and Ranking Methodologies

The statistical framework for NMA involves synthesizing both direct and indirect evidence to generate effect estimates for all possible pairwise comparisons within the network [6]. Both frequentist and Bayesian approaches are available, with the frequentist approach implemented in software such as the R package netmeta and tools like MetaInsight, which provides a web-based interface for conducting NMA without requiring advanced programming skills [25].

A key output of NMA is the ranking of interventions, often presented as probabilities for each treatment being the best, second best, and so on [6]. The Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) value provides a numerical summary of these ranking probabilities, with higher values indicating a more favorable ranking position [7]. However, the protocol should explicitly caution against overinterpreting these rankings without considering the magnitude of actual differences between interventions and the certainty of the evidence [6] [7].

Table 2: Key Methodological Considerations in NMA Protocol Design

| Methodological Aspect | Protocol Requirements | Recommended Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Network Geometry | Describe all interventions and available comparisons | Create network diagram with nodes (interventions) and edges (direct comparisons) [6] |

| Transitivity Assessment | Evaluate similarity across studies in effect modifiers | Assess distribution of patient characteristics, intervention details, outcome definitions across comparisons [6] |

| Statistical Synthesis | Specify model for combining direct and indirect evidence | Choose between frequentist or Bayesian framework, fixed or random effects models [25] [6] |

| Incoherence Assessment | Evaluate consistency between direct and indirect evidence | Use side-splitting or node-splitting methods, design-by-treatment interaction model [6] |

| Certainty Assessment | Evaluate confidence in NMA estimates | Apply GRADE or CINeMA frameworks for network estimates [6] [7] |

Updates and Evolving Methodological Standards

The field of NMA is rapidly evolving, necessitating ongoing updates to reporting guidelines. A 2025 scoping review identified 61 studies relevant to updating PRISMA-NMA, including 23 guidance documents and 38 overviews assessing the completeness or quality of NMA reporting [26]. This review identified 37 additional reporting items that will inform the upcoming PRISMA-NMA update through a Delphi consensus process [26].

Several pressing reasons necessitate updating the 2015 PRISMA-NMA guideline. First, assessments of reporting completeness have revealed that some NMA elements remain incompletely reported, suggesting that additional items or modifications to existing items may be needed [23]. Second, important methodological advances have occurred since 2015, including techniques for modeling complex interventions, handling missing data, assessing transitivity, and evaluating certainty of evidence [23]. Third, the PRISMA statement was updated in 2020 to reflect advances in systematic review conduct and reporting, and the NMA extension requires alignment with this updated structure [23] [27].

The updating process follows rigorous methodology, including comprehensive scoping reviews, Delphi surveys involving diverse stakeholders, consensus meetings, and the development of explanation and elaboration documents [23] [26]. This process also incorporates perspectives previously omitted from guideline development, including patients and the public, alongside journal editors, clinicians, policymakers, statisticians, and methodologists [23].

Figure 2: PRISMA-NMA Guideline Development and Update Timeline

Research Reagent Solutions: Tools for NMA Implementation

Successful implementation of a PRISMA-NMA compliant review requires familiarity with specialized software tools and methodological resources. These "research reagents" facilitate various stages of the NMA process, from data synthesis to visualization and reporting.

MetaInsight represents a particularly valuable tool for researchers new to NMA, as it provides a web-based, point-and-click interface for conducting NMAs without requiring knowledge of specialist statistical packages [25]. This open-access tool leverages established R routines (specifically the netmeta package) but operates behind the scenes on a webserver, eliminating the need for users to install statistical software [25]. MetaInsight supports both binary and continuous outcomes for fixed and random effects models and facilitates sensitivity analyses through interactive inclusion and exclusion of studies [25].

For advanced applications and customized analyses, statistical programming environments remain essential. R with packages such as netmeta for frequentist approaches and BUGS or JAGS for Bayesian implementations provide greater flexibility but require substantial statistical programming expertise [25] [6]. The Cochrane Handbook provides comprehensive guidance on the application of these methods, though it appropriately notes that "authors will need a knowledgeable statistician to plan and execute these methods" [6].

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PRISMA-NMA Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Access Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA-NMA Checklist [21] | Ensures complete reporting of NMA methods and findings | Freely available from prisma-statement.org |

| Statistical Software | R with netmeta package [25] | Conducts frequentist NMA with comprehensive statistical options | Open source, requires programming knowledge |

| Web Applications | MetaInsight [25] | Provides point-and-click interface for NMA without coding | Freely available web application, no installation required |

| Methodological Guidance | Cochrane Handbook Chapter 11 [6] | Offers comprehensive guidance on NMA methodology and conduct | Freely available from cochrane.org/handbook |

Comparative Analysis of NMA Reporting Completeness

Empirical evaluations of NMA reporting have identified persistent gaps despite the availability of the PRISMA-NMA guideline. A 2025 scoping review highlighted that key recommendations on statistical methods were often missed in NMA reporting [26]. This finding aligns with earlier observations that some elements of the PRISMA-NMA checklist are incompletely reported, even in high-impact journals [23].

The forthcoming update to PRISMA-NMA aims to address these reporting gaps by incorporating items related to recent methodological developments. These include methods for assessing effect modification, defining intervention nodes in complex networks, implementing advanced statistical models, and applying frameworks for evaluating the certainty of evidence from NMAs [23] [26]. The updated guideline will also align with the structure of PRISMA 2020, which uses broad elements rather than the more specific items of the original PRISMA statement [23].

Transparent reporting of NMAs has implications beyond academic completeness. Inadequate reporting hampers proper quality assessment, potentially leading to erroneous health recommendations and negative impacts on patient care and policy [23]. Furthermore, as NMAs are increasingly used by health technology assessment bodies like NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) to inform coverage decisions, complete reporting becomes essential for justifying resource allocation decisions [25].

The development of the PRISMA-NMA update incorporates multi-stakeholder perspectives, including patients and the public, to ensure that the reporting guideline addresses aspects important to all consumers of systematic reviews [23]. This inclusive approach strengthens the relevance and applicability of the guideline across diverse user groups, from clinical decision-makers to policy developers and patient advocates.

The PRISMA-NMA guideline provides an essential framework for conducting and reporting systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses, particularly in the context of therapeutic equivalence research. As the methodology continues to evolve with advancements in statistical modeling, evidence assessment, and implementation tools, the reporting standards must similarly advance to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and utility for decision-makers.