Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparisons: A Comprehensive Guide for Evidence Synthesis in Drug Development

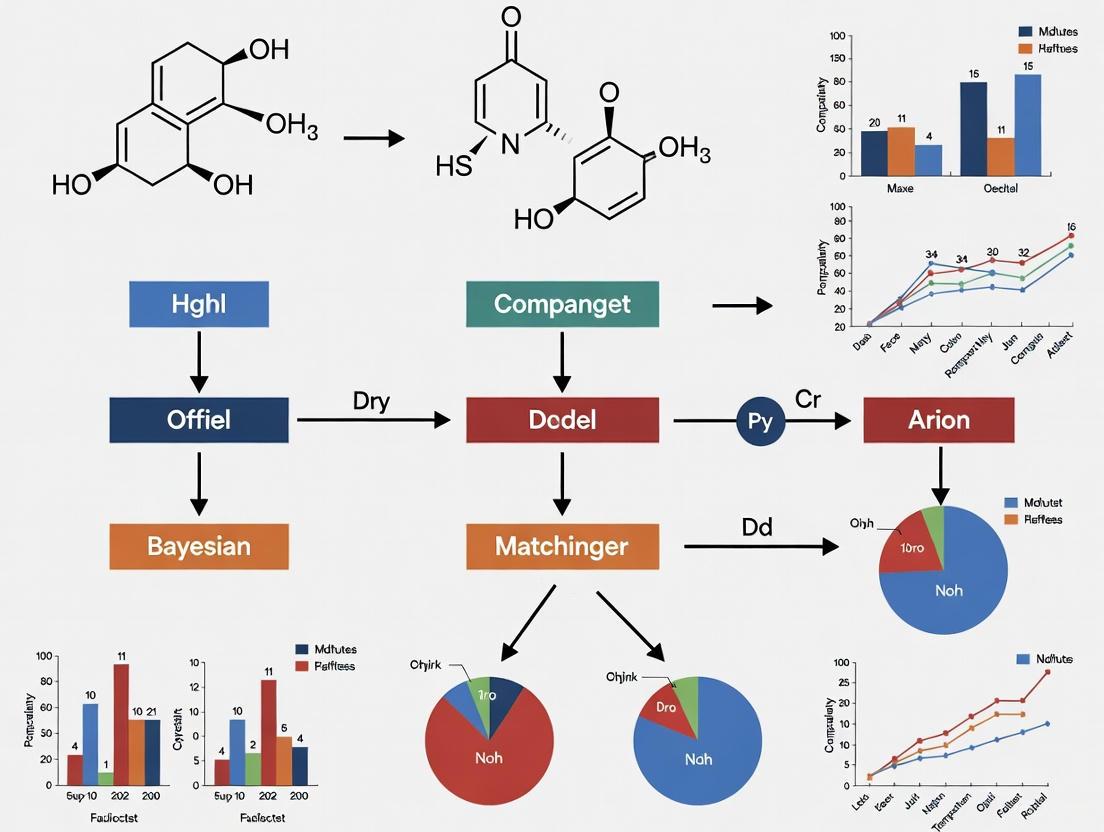

This article provides a comprehensive guide to applying Bayesian models for Mixed Treatment Comparisons (MTC), also known as Network Meta-Analysis, in biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparisons: A Comprehensive Guide for Evidence Synthesis in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to applying Bayesian models for Mixed Treatment Comparisons (MTC), also known as Network Meta-Analysis, in biomedical and pharmaceutical research. It covers foundational concepts, including the transitivity and consistency assumptions essential for valid MTC. The guide details methodological implementation using Bayesian hierarchical models, Markov Chain Monte Carlo estimation, and treatment ranking procedures. It addresses common challenges like outcome reporting bias, heterogeneous populations, and complex evidence networks, offering practical troubleshooting strategies. Finally, it compares Bayesian and frequentist approaches, demonstrating how Bayesian methods provide more intuitive probabilistic results for clinical decision-making. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage advanced evidence synthesis for personalized medicine and robust treatment recommendations.

Core Principles and Assumptions of Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparisons

Network meta-analysis (NMA), also referred to as multiple treatment comparison (MTC) or mixed treatment comparison, represents an advanced statistical methodology that synthesizes evidence from multiple studies evaluating three or more interventions [1] [2] [3]. This approach extends beyond conventional pairwise meta-analysis by enabling simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments within a unified statistical framework, even for interventions that have never been directly compared in head-to-head clinical trials [4] [3].

The fundamental advancement of NMA lies in its ability to incorporate both direct evidence (from head-to-head comparisons within trials) and indirect evidence (estimated through common comparators) to derive comprehensive treatment effect estimates across all interventions in the network [4] [3]. This methodology provides clinicians, researchers, and policymakers with a powerful tool for determining comparative effectiveness and safety profiles across all available interventions for a specific condition, thereby informing evidence-based decision-making in healthcare [2] [4].

Statistical Foundations and Framework

Core Conceptual Framework

The statistical foundation of network meta-analysis rests upon the integration of direct and indirect evidence through connected networks of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [2]. A connected network requires that each intervention is linked to every other intervention through a pathway of direct comparisons, forming what is visually represented as a network plot or graph [3]. In these visual representations, nodes (typically circles) represent interventions, while lines connecting them represent available direct comparisons from clinical trials [3].

NMA operates under several key assumptions that extend beyond those required for standard pairwise meta-analysis. The transitivity assumption requires that studies comparing different sets of treatments are sufficiently similar in their clinical and methodological characteristics to permit valid indirect comparisons [2]. The consistency assumption (sometimes called coherence) posits that direct and indirect evidence within the network are in agreement—that is, the effect estimates derived from direct comparisons align statistically with those obtained through indirect pathways [3].

Bayesian versus Frequentist Approaches

Network meta-analysis can be implemented through two primary statistical frameworks: Bayesian and frequentist methods [1]. While both approaches can yield similar results with large sample sizes, they differ fundamentally in their philosophical foundations and computational implementation [1].

The Bayesian framework incorporates prior probability distributions along with the likelihood from observed data to generate posterior distributions for parameters of interest [1] [5]. This approach calculates the probability that a research hypothesis is true by combining information from the current data with previously known information (prior probability) [1]. The Bayesian method is particularly advantageous for NMA as it does not rely on large sample assumptions, can incorporate prior clinical knowledge, and naturally produces probability statements about treatment rankings [1] [5]. Key components of Bayesian analysis include:

- Prior distributions: Represent pre-existing knowledge or beliefs about parameters before observing the current data [1] [5]

- Likelihood function: Reflects the probability of the observed data given the parameters [5]

- Posterior distributions: Represent updated knowledge about parameters after combining prior distributions with the observed data [1] [5]

In contrast, the frequentist approach determines whether to accept or reject a research hypothesis based on significance levels (typically p < 0.05) and confidence intervals derived solely from the observed data, without incorporating external information [1]. Frequentist methods compute the probability of obtaining the observed data (or more extreme data) assuming the null hypothesis is true, based on the concept of infinite repetition of the experiment [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Bayesian and Frequentist Approaches to NMA

| Feature | Bayesian Approach | Frequentist Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Probabilistic; parameters as random variables | Fixed parameters; repeated sampling framework |

| Prior Information | Explicitly incorporated via prior distributions | Not incorporated |

| Result Interpretation | Posterior probability distributions for parameters | Point estimates with confidence intervals and p-values |

| Treatment Rankings | Direct probability statements (e.g., SUCRA values) | Based on point estimates |

| Computational Methods | Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation | Maximum likelihood or method of moments |

| Handling Complexity | Flexible for complex models and hierarchical structures | May have limitations with complex random-effects structures |

Bayesian Hierarchical Model for NMA

The Bayesian hierarchical model forms the statistical backbone for Bayesian network meta-analysis [5]. For a random-effects NMA, the model can be specified as follows:

For each study ( k ) comparing treatments ( a ) and ( b ), the observed effect size ( Y{kab} ) (e.g., log odds ratio, mean difference) is assumed to follow a normal distribution: [ Y{kab} \sim \mathcal{N}(\delta{kab}, sk^2) ] where ( \delta{kab} ) represents the underlying true treatment effect of ( a ) versus ( b ) in study ( k ), and ( sk^2 ) is the within-study variance [5].

The study-specific true effects ( \delta{kab} ) are assumed to follow a common distribution for each comparison: [ \delta{kab} \sim \mathcal{N}(d{ab}, \tau^2) ] where ( d{ab} ) represents the mean treatment effect for comparison ( a ) versus ( b ), and ( \tau^2 ) represents the between-study heterogeneity, assumed constant across comparisons [5].

The core of the NMA model lies in the connection between various treatment comparisons through consistency assumptions: [ d{ab} = d{1a} - d{1b} ] where ( d{1a} ) and ( d_{1b} ) represent the effects of treatments ( a ) and ( b ) relative to a common reference treatment (typically treatment 1) [5].

For multi-arm trials (trials with more than two treatment groups), the model accounts for the correlation between treatment effects within the same study by assuming the effects follow a multivariate normal distribution [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflow

Protocol Development for NMA

Implementing a robust network meta-analysis requires meticulous planning and execution according to established methodological standards. The following workflow outlines the key stages in conducting a Bayesian NMA:

Detailed Methodological Components

Systematic Literature Review and Data Collection

The foundation of any valid NMA is a comprehensive systematic review following established guidelines (e.g., Cochrane Handbook) [2] [3]. This process should include:

- Explicit eligibility criteria defining populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study designs (PICOS framework)

- Comprehensive search strategy across multiple electronic databases and clinical trial registries

- Dual independent study selection and data extraction to minimize bias

- Assessment of risk of bias in individual studies using validated tools (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Bias tool)

- Data extraction of study characteristics, patient demographics, and outcome data

Network Geometry and Connectivity

A crucial step in NMA is visualizing and evaluating the network structure [3]. The network plot should be created to illustrate:

- Nodes representing each intervention, with size potentially proportional to the number of patients or studies

- Edges representing direct comparisons, with thickness potentially proportional to the number of studies or precision

- Connectivity ensuring all interventions are connected through direct or indirect pathways

Model Implementation using Bayesian Methods

The Bayesian NMA model is typically implemented using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which iteratively sample from the posterior distributions of model parameters [1] [5]. The process involves:

- Specification of prior distributions for basic parameters (typically vague or weakly informative priors)

- Model fitting using MCMC algorithms (e.g., Gibbs sampling)

- Convergence diagnostics to ensure MCMC chains have reached the target posterior distribution (using statistics like Gelman-Rubin diagnostic)

- Posterior inference based on a sufficient number of post-convergence iterations

Table 2: Key Software Packages for Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis

| Software/Package | Description | Key Features | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| R package 'gemtc' | Implements Bayesian NMA using MCMC | Hierarchical models, treatment rankings, consistency assessment | R interface with JAGS |

| JAGS/OpenBUGS | MCMC engine for Bayesian analysis | Flexible model specification, various distributions | Standalone or through R |

| R package 'netmeta' | Frequentist approach to NMA | Graph-theoretical methods, net league tables | R |

| R2WinBUGS | Interface between R and WinBUGS | Allows running BUGS models from R | R to WinBUGS connection |

Analytical Implementation and Diagnostic Evaluation

Bayesian Computation and MCMC Simulation

The implementation of Bayesian NMA relies heavily on Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation methods, which numerically approximate the posterior distributions of model parameters [1]. The MCMC process involves:

- Initialization: Starting with initial values for all parameters

- Iterative sampling: Generating sequences of parameter values through a Markov process

- Burn-in period: Discarding initial iterations before the chain reaches stationarity

- Convergence assessment: Verifying that multiple chains with different starting values yield similar posterior distributions

- Posterior inference: Using post-convergence iterations to summarize posterior distributions (means, medians, credible intervals)

The MCMC algorithm effectively performs what can be conceptualized as a "reverse calculation" of the area under complex posterior distribution functions that may not follow standard statistical distributions [1].

Model Diagnostics and Assumption Verification

Critical evaluation of NMA outputs requires comprehensive diagnostic assessments:

Heterogeneity and Consistency Assessment

- Heterogeneity estimation: Evaluating between-study variance (τ²) across the network

- Local inconsistency: Using node-splitting methods to assess disagreement between direct and indirect evidence for specific comparisons

- Global inconsistency: Employing design-by-treatment interaction models to assess consistency across the entire network

- Sensitivity analyses: Exploring the impact of different prior distributions, exclusion of high-risk studies, or alternative model assumptions

Model Fit and Comparison

- Residual deviance: Assessing discrepancies between observed data and model predictions

- Deviance Information Criterion (DIC): Comparing fit of different models (e.g., fixed vs. random effects, consistency vs. inconsistency models)

- Leverage and influence diagnostics: Identifying studies exerting disproportionate influence on network estimates

Interpretation and Application of NMA Results

Treatment Effects and Ranking Metrics

Bayesian NMA provides several outputs to inform clinical decision-making:

- Relative treatment effects with 95% credible intervals for all possible pairwise comparisons, including those without direct evidence

- Treatment rankings indicating the relative performance of each intervention for specific outcomes

- Rank probabilities showing the probability of each treatment being the best, second best, etc.

- Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) values providing a numerical summary of ranking probabilities (ranging from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better performance) [4]

Clinical and Policy Applications

The results of NMA directly inform evidence-based medicine and healthcare decision-making by:

- Identifying the most effective interventions across multiple outcomes (efficacy, safety, quality of life)

- Informing clinical practice guidelines with comprehensive comparative effectiveness evidence

- Guiding resource allocation and formulary decisions by healthcare systems

- Identifying evidence gaps for future research priorities

- Supporting health technology assessment and regulatory decision-making

Table 3: Interpretation of Key NMA Outputs for Clinical Decision-Making

| Output Metric | Interpretation | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Effect (95% CrI) | Estimated difference between treatments with uncertainty interval | Direct comparison of treatment efficacy/safety |

| Rank Probabilities | Probability of each treatment having specific rank (1st, 2nd, etc.) | Understanding uncertainty in treatment performance hierarchy |

| SUCRA Values | Numerical summary of overall ranking (0-1 scale) | Comparative performance metric across multiple outcomes |

| Between-Study Heterogeneity (τ²) | Estimate of variability in treatment effects across studies | Assessment of consistency of effects across different populations/settings |

| Node-Split P-values | Statistical test for direct-indirect evidence disagreement | Evaluation of network consistency and result reliability |

Advanced Considerations and Methodological Challenges

Addressing Complexity in Network Meta-Analysis

Advanced applications of NMA require careful consideration of several methodological challenges:

- Multi-arm trials: Properly accounting for correlation between treatment effects from trials with more than two intervention groups [5]

- Sparse networks: Interpretation challenges when limited direct evidence exists for specific comparisons

- Effect modifiers: Assessing and adjusting for clinical or methodological variables that may modify treatment effects across studies

- Scale and link functions: Selecting appropriate models for different outcome types (binary, continuous, time-to-event)

- Network geometry: Understanding how the structure of the evidence network influences the precision and reliability of indirect estimates

Reporting Standards and Transparency

Comprehensive reporting of NMA findings is essential for interpretation and critical appraisal. Key reporting elements include:

- Complete network description with network diagram and summary of available direct evidence

- Clear specification of statistical models, prior distributions, and computational methods

- Assessment and reporting of model fit, heterogeneity, and consistency

- Transparent presentation of all treatment comparisons with measures of uncertainty

- Sensitivity analyses exploring the impact of methodological assumptions and potential biases

The Bayesian framework for network meta-analysis represents a powerful advancement in evidence synthesis, enabling comprehensive comparison of multiple interventions through integration of direct and indirect evidence. When properly implemented with appropriate attention to methodological assumptions and statistical rigor, NMA provides invaluable information for healthcare decision-makers facing complex choices among multiple treatment options. The continued refinement of Bayesian methods for NMA promises to further enhance the reliability and applicability of this important methodology in evidence-based medicine.

Bayesian statistics is a powerful paradigm for data analysis that redefines probability as a degree of belief, treating parameters as random variables with probability distributions that reflect our uncertainty [6]. This contrasts with the frequentist view, where probability is a long-run frequency and parameters are fixed, unknown constants. The Bayesian framework allows for direct probability statements about parameters, such as "there is a 95% probability that the true mean lies between X and Y," aligning more closely with intuitive interpretations often mistakenly applied to frequentist confidence intervals [6].

The essence of the Bayesian paradigm lies in its iterative learning process, which follows a consistent logic: start with an initial belief (prior), gather data (likelihood), and combine these to form an updated belief (posterior). This process of belief updating is central to scientific inquiry and provides a coherent framework for learning from data across various applications in biostatistics, clinical research, and drug development [6].

Foundational Elements

Bayes' Theorem: The Core Engine

The mathematical foundation of Bayesian inference is Bayes' Theorem, a simple formula with profound implications for statistical reasoning and analysis [6]. The theorem is expressed as:

P(θ∣Data) = [P(Data∣θ) ⋅ P(θ)] / P(Data)

Where:

- P(θ∣Data) is the posterior distribution of parameters θ given the observed data

- P(Data∣θ) is the likelihood function of the data given parameters θ

- P(θ) is the prior distribution of parameters θ

- P(Data) is the marginal likelihood of the data

Often, the theorem is expressed proportionally as: Posterior ∠Likelihood × Prior [6]. This relationship highlights that the posterior distribution represents a compromise between our initial beliefs (prior) and what the new data reveals (likelihood).

Table 1: Components of Bayes' Theorem

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior | P(θ∣Data) | Updated belief about parameters after observing data | Final inference, uncertainty quantification |

| Likelihood | P(Data∣θ) | Probability of observing data given specific parameters | Connects parameters to observed data |

| Prior | P(θ) | Initial belief about parameters before observing data | Incorporates existing knowledge or constraints |

| Marginal Likelihood | P(Data) | Overall probability of data across all parameter values | Normalizing constant, model evidence |

A Simple Biostatistical Example: Diagnostic Testing

Consider a new diagnostic test for a rare disease with a prevalence of 1 in 1000. The test has 99% sensitivity (P(Test Positive∣Has Disease) = 0.99) and 95% specificity (P(Test Negative∣No Disease) = 0.95) [6].

Using Bayes' Theorem, we calculate the probability that an individual actually has the disease given a positive test result:

P(Has Disease∣Test Positive) = [P(Test Positive∣Has Disease) ⋅ P(Has Disease)] / P(Test Positive)

P(Test Positive) = (0.99 ⋅ 0.001) + (0.05 ⋅ (1−0.001)) = 0.05094

P(Has Disease∣Test Positive) = (0.99 ⋅ 0.001) / 0.05094 ≈ 0.0194 or 1.94% [6]

This counterintuitive result—where a positive test from a highly accurate method yields only a 1.94% probability of having the disease—underscores the critical role of the prior (the disease prevalence) in Bayesian reasoning [6].

Table 2: Bayesian Methods Comparison in Clinical Research

| Method | Key Features | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power Priors | Weighted log-likelihood from historical data [7] | Incorporating historical controls, registry data | Straightforward implementation, intuitive weighting | Sensitivity to prior weight selection |

| Meta-Analytic-Predictive (MAP) Prior | Accounts for heterogeneity via random-effects meta-analysis [7] | Multi-regional clinical trials, borrowing across studies | Explicit modeling of between-trial heterogeneity | Requires exchangeability assumption |

| Commensurate Prior | Adaptively discounts historical data based on consistency [7] | Bayesian dynamic borrowing, real-world evidence incorporation | Robust to prior-data conflict | Computational complexity |

| Multi-Source Dynamic Borrowing (MSDB) Prior | Novel heterogeneity metric (PPCM), addresses baseline imbalance [7] | Incorporating multiple historical datasets (RCTs and RWD) | No exchangeability assumption, handles baseline imbalances | Complex implementation, computational intensity |

| Robust MAP Prior | Weakly informative component added to MAP prior [7] | Clinical trials with potential prior-data conflict | More effective discounting of conflicting data | Requires specification of robust mixture weight |

Table 3: MCMC Sampling Algorithms in Bayesian Analysis

| Algorithm | Mechanism | Convergence Diagnostics | Software Implementation | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolis-Hastings | Proposal-acceptance based on likelihood ratio [6] | Trace plots, acceptance rate | Stan, PyMC, custom code | General-purpose sampling, moderate dimensions |

| Gibbs Sampling | Iterative sampling from full conditional distributions [6] | Autocorrelation plots, Geweke diagnostic | JAGS, BUGS, PyMC | Hierarchical models, conjugate structures |

| Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) | Uses gradient information for efficient exploration [6] | Gelman-Rubin statistic (RÌ‚), E-BFMI | Stan (primary), PyMC | High-dimensional complex posteriors |

| No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) | Self-tuning variant of HMC [6] | Effective Sample Size (ESS), divergences | Stan (default), PyMC | Automated sampling, complex models |

Advanced Bayesian Protocols

Protocol: Multi-Source Dynamic Borrowing for Clinical Trials

The MSDB prior framework dynamically incorporates information from multiple historical sources (external RCTs and real-world data) while addressing baseline imbalances and heterogeneity [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- Current RCT dataset

- Historical clinical trial data

- Real-world data (registries, electronic health records)

- Statistical software with Bayesian capabilities (Stan, PyMC, or custom implementations)

Procedure:

Propensity Score Stratification

- Define propensity score as probability a patient belongs to current trial data using multinomial logistic regression: P(Study = Current∣X) [7]

- Estimate propensity scores using maximum likelihood estimation

- Create strata based on propensity score quantiles, ensuring approximately equal number of current RCT patients per stratum

- Trim external data patients falling outside propensity score range of current trial patients

Stratum-Specific Prior Construction

- Model patient survival times using piecewise exponential distribution within each time interval

- Assume total exposure time follows Gamma distribution with shape parameter as number of events and scale parameter as hazard rate

- Apply log transformation to hazard rates: log(λ) ~ Normal(μ, σ²) [7]

- Use weakly informative normal priors for μ with large variance (e.g., 1000)

Prior-Posterior Consistency Measurement

- Calculate PPCM metric to quantify consistency between prior information and observed data

- Compute posterior predictive probability function updated using prior information

- Measure predictive probability that is lower than current data [7]

- Use PPCM values to determine borrowing weights for historical data

Multi-Source Integration

- Merge prior distributions by considering heterogeneity between studies

- Dynamically adjust borrowing strength based on PPCM consistency measures

- Completely transform to non-informative prior when heterogeneity is excessive [7]

Validation:

- Compare performance using power, type I error, bias, and mean squared error across methods

- Application to case study (e.g., isatuximab in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma) [7]

Protocol: Chaining Bayesian Inference with Empirical Priors

This protocol addresses situations where Bayesian inferences need to be chained on a data stream without analytic form of the posterior, using kernel density estimates from previous posterior draws [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- Sequence of datasets: (xâ‚, yâ‚), (xâ‚‚, yâ‚‚), …, (xâ‚™, yâ‚™)

- Posterior draws from previous analysis: θpost(1), …, θpost(M) ~ p(θ∣xâ‚, yâ‚)

- Computational resources for MCMC sampling

Procedure:

Initial Model Fitting

- Fit initial model p(θ, y∣x) to first dataset (xâ‚, yâ‚)

- Obtain posterior draws θpost(1), …, θpost(M) ~ p(θ∣xâ‚, yâ‚)

- Assume posterior draws can be shared across analyses [8]

Kernel Density Prior Construction

Efficient Metropolis Sampling

- Implement Metropolis sampling using only nearest neighbors of θ

- Utilize graph-enabled fast MCMC sampling for efficiency [8]

- Alternative: Use Stan for normal approximation implementation

Sequential Bayesian updating

- Use approximate posterior p(θ∣yâ‚, xâ‚) as prior for analyzing new data (xâ‚‚, yâ‚‚)

- Compute: p(θ∣xâ‚, xâ‚‚, yâ‚, yâ‚‚) ∠p(y₂∣θ, xâ‚‚) · p(θ∣yâ‚, xâ‚) [8]

- Continue chaining process for subsequent datasets

Considerations:

- Set variance parameter h to control prior concentration

- Determine optimal number of posterior draws M based on dimensionality

- Handle constrained parameters through appropriate transformations

- Compare with multivariate normal approximation approaches [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparisons

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Context | Key Features | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stan | Probabilistic programming for Bayesian inference [6] | Complex hierarchical models, HMC sampling | NUTS sampler, differentiable probability functions | Requires programming expertise, good for complex models |

| JAGS/BUGS | MCMC sampling for Bayesian analysis [6] | Generalized linear models, conjugate models | Declarative language, automatic sampler selection | User-friendly, but less efficient for complex models |

| PyMC (Python) | Probabilistic programming framework [6] | Bayesian machine learning, custom distributions | Gradient-based inference, Theano/Aesara backend | Python ecosystem integration, growing community |

| RBesT | R Package for Bayesian Evidence Synthesis [8] | Meta-analytic-predictive priors, clinical trials | Pre-specified prior distributions, mixture normal approximations | Specialized for biostatistics, regulatory acceptance |

| brms | R Package for Bayesian regression models [6] | Multilevel models, formula interface | Stan backend, lme4-style syntax | User-friendly for R users, extensive model family support |

| Propensity Score Tools | Address baseline imbalances in historical data [7] | Incorporating real-world data, dynamic borrowing | Multinomial logistic regression, stratification | Essential for observational data incorporation |

| Geninthiocin | Geninthiocin, MF:C50H49N15O15S, MW:1132.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| 3-O-Acetylpomolic acid | 3-O-Acetylpomolic acid, MF:C32H50O5, MW:514.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Mixed Treatment Comparisons

Bayesian methods provide particularly powerful approaches for mixed treatment comparisons (MTCs), also known as network meta-analysis, where the framework naturally handles complex evidence structures and uncertainty propagation.

Key Advantages for MTCs:

- Coherent Uncertainty Propagation: Bayesian methods naturally propagate uncertainty through all parameters in the network, providing more accurate confidence intervals for treatment effects [6]

- Flexible Hierarchical Modeling: Random-effects models can be implemented to account for heterogeneity across studies while maintaining network connectivity [7]

- Incorporation of Diverse Evidence: The MSDB framework enables borrowing of strength from real-world evidence and historical data while adjusting for baseline characteristics [7]

- Probabilistic Ranking: Direct computation of probability distributions for treatment rankings, providing more informative conclusions for decision-makers [6]

Implementation Considerations:

- Use weakly informative priors for heterogeneity parameters to avoid over-smoothing in sparse networks

- Implement consistency models assuming agreement between direct and indirect evidence

- Use node-splitting models to assess inconsistency in specific treatment comparisons

- Apply meta-regression to adjust for effect modifiers across studies

The Bayesian framework's flexibility in handling complex modeling structures, combined with its principled approach to evidence synthesis, makes it particularly suitable for mixed treatment comparisons where multiple data sources with varying quality and relevance need to be integrated for comprehensive treatment effect estimation.

The validity of a Mixed Treatment Comparison (MTC), also known as a Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), depends on several critical assumptions. These analyses simultaneously synthesize evidence from networks of clinical trials to compare multiple interventions, even when some have not been directly compared head-to-head [9] [10]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals employing Bayesian MTC models, verifying the underlying assumptions of transitivity, consistency, and homogeneity (or its related concept, similarity) is not merely a statistical formality but a fundamental prerequisite for generating credible and clinically useful results [11] [12]. Violations of these assumptions can introduce bias and invalidate the conclusions of an otherwise sophisticated analysis. This document outlines detailed protocols for assessing these assumptions, framed within a broader research thesis on applying Bayesian MTC models.

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

A clear understanding of the core assumptions is essential before undertaking their assessment.

Transitivity is a logical and clinical assumption that forms the bedrock of indirect comparisons. It posits that the studies included in the network are sufficiently similar, on average, in all important clinical and methodological characteristics that could influence the relative treatment effects [13] [11]. This means that if we have trials comparing treatment A vs. B and A vs. C, the patients, interventions, and study designs in these two sets of trials are similar enough that we can logically infer the effect of B vs. C through the common comparator A. Transitivity is a qualitative assumption assessed at the study level [11] [12].

Homogeneity/Similarity is often discussed alongside transitivity. While transitivity concerns the entire network, homogeneity traditionally refers to the statistical variability in treatment effects within a single pairwise comparison (e.g., among all A vs. B studies) [11] [12]. The methodological concept ensuring that studies are comparable enough to be combined is also termed similarity [11]. It is examined by assessing the distribution of potential effect modifiers across the different treatment comparisons.

Consistency is the statistical manifestation of transitivity. It means that the estimated treatment effect from a direct comparison (e.g., from trials directly comparing B and C) is in agreement with the estimate derived from indirect comparisons (e.g., comparing B vs. A and C vs. A) [9] [13]. In a network where both direct and indirect evidence exist for a particular comparison, this assumption can be tested statistically.

Table 1: Summary of Critical Assumptions in Mixed Treatment Comparisons

| Assumption | Conceptual Level | Core Question | Primary Method of Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transitivity | Logical/Clinical | Can the studies in the network be fairly compared to form a valid indirect comparison? | Qualitative evaluation of study characteristics and effect modifiers [13]. |

| Homogeneity/Similarity | Methodological/Statistical | Are the studies within each direct comparison similar enough to be pooled? | Evaluation of clinical/methodological characteristics and statistical heterogeneity (e.g., I²) within pairwise comparisons [11] [12]. |

| Consistency | Statistical | Do the direct and indirect estimates of the same treatment effect agree? | Statistical tests (e.g., design-by-treatment, node-splitting) and graphical methods [13] [11]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical and statistical relationships between these core assumptions and the analysis process.

Protocol for Assessing Transitivity and Similarity

The assessment of transitivity and similarity is a methodological process that begins during the systematic review phase.

Experimental Workflow for Transitivity Assessment

The evaluation of transitivity is a qualitative, study-level process focused on identifying and comparing effect modifiers across the different treatment comparisons in the network [12].

Table 2: Key Domains for Evaluating Transitivity and Similarity

| Domain | Description | Practical Application | Common Effect Modifiers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Clinical characteristics of participants in the studies. | Compare baseline disease severity, age, gender, comorbidities, prior treatments, and diagnostic criteria across studies for each comparison. | Disease severity, genetic biomarkers, treatment history. |

| Intervention (I) | Specifics of the treatment regimens being investigated. | Ensure dosing, administration route, treatment duration, and concomitant therapies are comparable. | Drug formulation, dose intensity, surgical technique. |

| Comparator (C) | The control or standard therapy used in the trials. | Verify that control groups (e.g., placebo, active drug, standard care) are comparable. | Type of placebo, dose of active comparator. |

| Outcome (O) | The measured endpoint and how it was defined and assessed. | Confirm outcome definitions, measurement scales, timing of assessment, and follow-up duration are consistent. | Outcome definition (e.g., response rate), time point of measurement. |

| Study Design (S) | Methodological features of the included trials. | Assess and compare risk of bias, randomization method, blinding, and statistical analysis plan. | Study quality, blinding, multi-center vs. single-center. |

Detailed Methodology

- Identify Potential Effect Modifiers: Prior to analysis, systematically list clinical and methodological factors that are known, or suspected, to influence the relative treatment effects for the specific clinical question [13] [12]. This is based on clinical expertise and background knowledge.

- Extract Data on Effect Modifiers: During data extraction, systematically collect information on all identified potential effect modifiers for every included study.

- Compare the Distribution: Visually and statistically compare the distribution of these effect modifiers across the different treatment comparisons. For example, create summary tables or graphs showing the mean disease severity in A vs. B trials versus A vs. C trials. A notable imbalance in the distribution of a key effect modifier threatens the transitivity assumption.

- Sensitivity and Meta-Regression Analysis: If imbalance is suspected, consider conducting sensitivity analyses by excluding studies that are clear outliers. Alternatively, use meta-regression within the NMA model to adjust for continuous or categorical effect modifiers, if the data allow [11].

Protocol for Assessing Homogeneity

Homogeneity is assessed statistically within each direct pairwise comparison after the qualitative similarity assessment.

Experimental Protocol

- Perform Pairwise Meta-Analyses: Conduct standard pairwise meta-analyses for every direct comparison in the network (e.g., all A vs. B studies, all A vs. C studies) using both fixed-effect and random-effects models.

- Quantify Statistical Heterogeneity: For each pairwise meta-analysis, calculate the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance [12]. Cochran's Q test can also be used, though it has low power when few studies are available.

- Interpret the Results:

- I² = 0%: No observed heterogeneity.

- I² > 50%: May be considered substantial heterogeneity [12].

- Investigate Sources of Heterogeneity: If substantial heterogeneity is identified (I² > 50%), investigate potential sources by returning to the transitivity/similarity assessment. Explore the influence of clinical or methodological factors through subgroup analysis or meta-regression for that specific comparison [11] [12].

Protocol for Assessing Consistency

Consistency is evaluated statistically in networks where both direct and indirect evidence exist for one or more comparisons (forming closed loops).

Experimental Workflow and Statistical Tests

Several statistical approaches can be used to evaluate consistency. The following workflow outlines a common strategy:

Global Approaches

Global approaches assess inconsistency across the entire network simultaneously.

- Design-by-Treatment Interaction Model: This is a comprehensive method that accounts for different sources of inconsistency, both from loops of evidence and from different study designs (e.g., two-arm vs. three-arm trials) [11] [14]. It is typically implemented using a hierarchical model within a Bayesian or frequentist framework. The model is fitted and compared to a consistency model. A significant difference (e.g., via deviance information criterion (DIC) in Bayesian analysis or a Wald test) suggests global inconsistency [11].

Local Approaches

Local approaches pinpoint the specific comparison(s) where direct and indirect evidence disagree.

- Node-Splitting Method: This method "splits" the information for a particular node (treatment comparison) into direct and indirect evidence. It then statistically tests the difference between the direct estimate and the indirect estimate for that specific comparison [11]. A significant p-value (e.g., < 0.05) indicates local inconsistency for that node. This is a powerful tool for diagnosing problems but should be adjusted for multiple testing.

Detailed Methodology for Node-Splitting

- Specify the Model: Using statistical software (e.g.,

gemtcin R, WinBUGS), specify a node-splitting model for the network. - Run the Analysis: Fit the model, which will estimate both direct and indirect evidence for each closed loop in the network.

- Examine Output: Review the output for the p-values and confidence/intervals of the difference between direct and indirect estimates for each comparison.

- Address Inconsistency: If inconsistency is found, investigate its causes. Revisit the transitivity assessment for the studies involved in the inconsistent loop. Consider excluding studies with a high risk of bias that may be driving the inconsistency, or use advanced models that can account for inconsistency [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successfully implementing these protocols requires a suite of statistical and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Implementing MTC Assumption Assessments

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application in Assumption Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | An open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics. | Primary platform for conducting all statistical analyses, including meta-analysis, NMA, and inconsistency tests [9] [11]. |

netmeta package (R) |

A frequentist package for NMA. | Performs NMA, provides network plots, and includes statistical tests for heterogeneity and inconsistency [14]. |

gemtc package (R) |

An interface for Bayesian NMA using JAGS/BUGS. | Used for Bayesian NMA models, node-splitting analyses, and assessing model fit (e.g., DIC) [9] [11]. |

| CINeMA Software | A web application and R package for Confidence in NMA. | Systematically guides users through the evaluation of within-study bias, indirectness, heterogeneity, and incoherence, applying the GRADE framework to NMA results [14]. |

| Stata Software | A commercial statistical software package. | Can perform NMA using specific user-written commands (e.g., network group) for both frequentist and Bayesian analyses [9] [11]. |

| GRADE Framework for NMA | A methodological framework for rating the quality of evidence. | Provides a structured approach to downgrade confidence in NMA results due to concerns with risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias [14]. |

| NH2-C2-NH-Boc-d4 | NH2-C2-NH-Boc-d4, MF:C7H16N2O2, MW:164.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S)-(+)-Ascochin | (S)-(+)-Ascochin, MF:C12H10O5, MW:234.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The rigorous application of the protocols outlined herein for assessing transitivity, homogeneity, and consistency is non-negotiable for producing trustworthy evidence from Mixed Treatment Comparisons. These assumptions are interconnected, and the assessment process is iterative. Within the context of a thesis on Bayesian MTC models, this document provides a foundational framework. Researchers must transparently report their methods for evaluating these assumptions, as this directly impacts the confidence that clinicians, policymakers, and drug development professionals can place in the resulting treatment rankings and effect estimates.

Understanding Direct, Indirect, and Mixed Evidence in a Network

Network meta-analysis (NMA) is a powerful statistical technique that allows for the simultaneous comparison of three or more interventions by combining evidence from a network of studies [13]. This approach addresses a common challenge in evidence-based medicine: decision-makers often need to choose between multiple competing interventions for a condition, but head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are not available for all possible comparisons [13]. A network of interventions is formed by any set of studies that connects three or more interventions through direct comparisons [13]. The core strength of NMA lies in its ability to synthesize both direct evidence (from studies that directly compare two interventions) and indirect evidence (estimated through a common comparator) to generate mixed evidence (the combined effect estimate from the entire network) for all pairwise comparisons, even those never evaluated in direct trials [13].

The Bayesian statistical framework is particularly well-suited for NMA because it offers a principled and transparent method for combining different sources of evidence and quantifying uncertainty [15]. It allows for the incorporation of prior knowledge or beliefs through prior distributions, which is especially valuable when data are sparse [16] [15]. Furthermore, Bayesian methods provide direct probabilistic interpretations of results, such as the probability that one treatment is superior to another, which is highly informative for decision-making [15].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Types of Evidence in a Network

Direct Evidence: This evidence comes from studies, typically RCTs, that directly compare two interventions of interest (e.g., Intervention A vs. Intervention B) within the same trial and with the same protocol [13]. It preserves the benefits of within-trial randomization and is generally considered the gold standard for comparative effectiveness.

Indirect Evidence: When two interventions (e.g., B and C) have not been compared directly in a trial, their relative effect can be estimated indirectly through a common comparator (e.g., Intervention A) [13]. Mathematically, the indirect estimate for the effect of B versus C (dBC) via comparator A is derived as dBC = dAC - dAB, where dAC and dAB are the direct estimates from A vs. C and A vs. B trials, respectively [13].

Mixed Evidence: In a network meta-analysis, mixed evidence (or mixed treatment comparison) refers to the comprehensive estimate that results from statistically combining all available direct and indirect evidence for a given comparison within a single, coherent model [13]. This usually yields more precise estimates than either direct or indirect evidence alone [13].

Fundamental Assumptions

The validity of indirect and mixed evidence hinges on three key assumptions [13]:

Transitivity: This is a core methodological assumption requiring that the different sets of studies included in the network (e.g., AB trials and AC trials) are similar, on average, in all important factors that may affect the relative treatment effects (effect modifiers), such as patient populations, study design, or outcome definitions [13]. In other words, one could imagine that the AB and AC trials are, on average, comparable enough that the participants in the B trials could hypothetically have been randomized to C, and vice versa.

Coherence (or Consistency): This is the statistical manifestation of transitivity. It occurs when the different sources of evidence (direct and indirect) for a particular treatment comparison are in agreement with each other [13]. For example, the direct estimate of B vs. C should be statistically consistent with the indirect estimate of B vs. C obtained via A.

Homogeneity: This refers to the variability in treatment effects between studies that are comparing the same pair of interventions. Excessive heterogeneity within a direct comparison can threaten the validity of the entire network.

Table 1: Glossary of Key Terms in Network Meta-Analysis

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Node | A point in a network diagram representing an intervention [13]. |

| Edge | A line connecting two nodes, representing the availability of direct evidence for that pair of interventions [13]. |

| Network Diagram | A graphical depiction of the structure of a network of interventions, showing which interventions have been directly compared [13]. |

| Effect Modifier | A study or patient characteristic (e.g., disease severity, age) that influences the relative effect of an intervention [13]. |

| Multi-Arm Trial | A randomized trial that compares more than two intervention groups simultaneously. These trials provide direct evidence on multiple edges in the network and must be analyzed correctly to preserve within-trial randomization [13]. |

Quantitative Landscape of Bayesian Methods in Applied Research

The application of Bayesian methods in medical research has seen significant growth. A recent bibliometric analysis of high-impact surgical journals from 2000 to 2024 identified 120 articles using Bayesian statistics, with a compounded annual growth rate of 12.3% [17]. This trend highlights the increasing adoption of these methods in applied research.

The use of Bayesian methods varies by study design and specialty. The same analysis found that the most common study designs employing Bayesian statistics were retrospective cohort studies (41.7%), meta-analyses (31.7%), and randomized trials (15.8%) [17]. In terms of surgical specialties, general surgery (32.5%) and cardiothoracic surgery (16.7%) were the most represented [17]. Regression-based methods were the most frequently used Bayesian technique (42.5%) [17].

However, the reporting quality of Bayesian analyses requires improvement. When assessed using the ROBUST scale (ranging from 0 to 7), the average score was 4.1 ± 1.6 [17]. Only 54% of studies specified the priors used, and a mere 29% provided justification for their choice of prior [17]. This underscores the need for better standardization and transparency in reporting.

Table 2: Application of Bayesian Statistics in Surgical Research (2000-2024)

| Characteristic | Findings (N=120 articles) |

|---|---|

| Compounded Annual Growth Rate | 12.3% [17] |

| Most Common Study Designs | Retrospective cohort studies (41.7%), Meta-analyses (31.7%), Randomized trials (15.8%) [17] |

| Top Represented Specialties | General Surgery (32.5%), Cardiothoracic Surgery (16.7%) [17] |

| Most Frequent Bayesian Methods | Regression-based analysis (42.5%) [17] |

| Average ROBUST Reporting Score | 4.1 ± 1.6 out of 7 [17] |

| Studies Specifying Priors | 54.0% [17] |

| Studies Justifying Priors | 29.0% [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Network Meta-Analysis

Protocol 1: Designing a Systematic Review for NMA

Objective: To systematically identify, select, and appraise all relevant studies for inclusion in a network meta-analysis.

- Define the Research Question: Formulate a clear question using the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome). Critically, define the set of competing interventions to be included in the network [13].

- Develop Search Strategy: Conduct comprehensive searches across multiple electronic databases (e.g., MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central). The search strategy should be designed to capture all studies for every possible pairwise comparison within the defined network [13].

- Study Selection and Data Extraction: Implement a systematic process for screening titles, abstracts, and full-text articles against pre-defined eligibility criteria. Extract data using standardized forms, including study characteristics, patient demographics, and outcome data for all intervention arms [13].

- Risk of Bias Assessment: Evaluate the methodological quality of each included study using appropriate tools (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomized trials) [13].

- Construct Network Geometry: Map the available direct comparisons to create a network diagram, which visually represents the evidence base and identifies where direct and indirect evidence will come from [13].

Protocol 2: Statistical Analysis Using a Bayesian Framework

Objective: To fit a Bayesian network meta-analysis model to obtain mixed treatment effect estimates for all pairwise comparisons and rank the interventions.

- Model Specification: Choose an appropriate statistical model. A common choice is a Bayesian hierarchical model using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for estimation [17] [15]. The model can be formulated on the mean difference (for continuous outcomes) or log odds ratio scale (for binary outcomes).

- Prior Selection: Specify prior distributions for the model parameters. For the treatment effects, non-informative or weakly informative priors (e.g., N(0, 1002)) are often used to let the data dominate the conclusions. For heterogeneity variance, a prior that constrains it to plausible values (e.g., half-normal or log-normal) is recommended [16].

- Model Implementation: Run the model in specialized Bayesian software such as JAGS, BUGS, or STAN [17] [15]. The analysis can be implemented using statistical software like R with packages such as

brms[16]. - Convergence Diagnostics: Check the convergence of the MCMC chains using diagnostics like the Gelman-Rubin statistic (R-hat) and trace plots to ensure the model has converged to a stable posterior distribution [15].

- Inference and Ranking: Extract the posterior distributions of the treatment effects for all pairwise comparisons. Calculate probability values for each treatment being the best, second best, etc., to create a hierarchy of treatments [13].

Protocol 3: Assessing Transitivity and Coherence

Objective: To evaluate the validity of the fundamental assumptions underlying the network meta-analysis.

- Assessment of Transitivity: Identify potential effect modifiers a priori based on clinical and methodological knowledge. Then, compare the distribution of these effect modifiers across the different direct comparisons in the network (e.g., by creating summary tables of study characteristics stratified by comparison) [13].

- Assessment of Coherence: Evaluate the statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence. This can be done using:

- Local Approaches: For a specific comparison, use the "node-splitting" method to separately estimate the direct, indirect, and mixed evidence and test for a significant disagreement [13].

- Global Approaches: Fit models that allow for and test the presence of incoherence anywhere in the entire network [13].

Visualization of Network Meta-Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key components of conducting a network meta-analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of Bayesian network meta-analysis requires a set of specialized statistical tools and software.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bayesian NMA

| Item | Category | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Software Environment | A free, open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics. It is the primary platform for implementing most Bayesian NMA analyses through its extensive package ecosystem [15]. |

| JAGS / BUGS | MCMC Engine | Standalone software for Bayesian analysis using Gibbs Sampling. They use their own model definition language and can be called from within R. Useful for a wide range of models but can be slower for complex models [17] [15]. |

| Stan (with brms) | MCMC Engine | A state-of-the-art platform for statistical modeling and high-performance statistical computation. It uses Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, which is often more efficient for complex models. The brms package in R provides a user-friendly interface to Stan [17] [16]. |

| Cochrane ROB Tool | Quality Assessment Tool | A standardized tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials. Assessing the quality of included studies is a critical step in evaluating the validity of a network meta-analysis [13]. |

| Non-informative Priors | Statistical Reagent | Prior distributions (e.g., very wide normal distributions) that are designed to have minimal influence on the posterior results, allowing the data to dominate the conclusions. They are a default starting point in many analyses [16]. |

| Informed Priors | Statistical Reagent | Prior distributions that incorporate relevant external evidence (e.g., from a previous meta-analysis or pilot study). They can be used to stabilize estimates, particularly in networks with sparse data [16] [15]. |

| ROBUST Checklist | Reporting Guideline | The Reporting of Bayes Used in Clinical Studies scale is a 7-item checklist used to assess and improve the quality and transparency of reporting in Bayesian analyses [17]. |

| L-Histidine hydrochloride hydrate | L-Histidine hydrochloride hydrate, CAS:5934-29-2, MF:C6H9N3O2.ClH.H2O, MW:209.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nrf2 activator-10 | Ethyl 4-chloro-1-methyl-2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate | High-purity Ethyl 4-chloro-1-methyl-2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, a key intermediate for antimicrobial research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Bayesian network meta-analyses are particularly powerful in specialized research contexts. One advanced application is in the analysis of N-of-1 trials, which are randomized multi-crossover trials conducted within a single individual to compare interventions personalized to that patient [15]. Bayesian multilevel (hierarchical) models can seamlessly combine data from a series of N-of-1 trials. This allows for inference at both the population level (e.g., the average treatment effect) and the individual level, borrowing strength across participants to improve estimation for each one [15]. This is ideal for personalized medicine and for studying rare diseases where large trials are not feasible.

Another area of development is the use of highly informed priors. For example, a research program can involve an initial pilot study (Study 1) analyzed with non-informative or weakly informative priors. The posterior distributions from this analysis can then be used as highly informed priors for a subsequent, refined study (Study 2) [16]. This approach allows for the cumulative building of evidence in an efficient and statistically rigorous manner, which is especially valuable in iterative or exploratory research.

As the field evolves, emphasis is being placed on improving the quality and standardization of reporting. The consistently low rates of prior specification and justification (54% and 29%, respectively) found in the recent literature indicate a key area for improvement [17]. Adherence to guidelines like the ROBUST checklist is crucial for enhancing the transparency, reproducibility, and ultimately, the utility of Bayesian network meta-analyses for drug development professionals and healthcare decision-makers [17].

In the realm of Bayesian mixed treatment comparisons (MTC) and network meta-analysis (NMA), the choice of data structure is a fundamental methodological decision that significantly influences model specification, computational implementation, and result interpretation. Researchers face two primary approaches for data extraction and organization: arm-level and contrast-level data structures. The growing adoption of Bayesian frameworks in medical research, with a compounded annual growth rate of 12.3% in surgical research specifically, underscores the importance of understanding these foundational elements [17]. This application note provides detailed protocols for both data extraction approaches, framed within the context of Bayesian MTC research for drug development professionals and researchers.

The Bayesian paradigm, which interprets probability as a degree of belief in a hypothesis and enables incorporation of prior evidence, offers particular advantages for synthesizing complex treatment networks [17]. However, the effectiveness of Bayesian MTC models depends critically on appropriate data structure selection, as this choice influences the modeling of heterogeneity, respect for randomization within trials, and the range of estimands that can be derived [18] [19].

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Arm-Level Data

Arm-level data (also referred to as arm-synthesis data) consists of the raw summary measurements for each treatment arm within a study [20]. This structure preserves the absolute outcome information for individual arms, allowing for the direct modeling of arm-specific parameters before deriving relative effects [19]. For binary outcomes, this typically includes the number of events and total participants for each arm. For continuous outcomes, this would include the mean, measure of dispersion (standard deviation or standard error), and sample size for each arm [20].

The arm-level approach forms the foundation for arm-synthesis models (ASMs), which combine the arm-level summaries in a statistical model, with relative treatment effects then constructed from these arm-specific parameters [19]. This approach has the advantage of being able to compute various estimands within the model, such as marginal risk differences, and allows for the derivation of additional parameters beyond direct contrasts [18] [19].

Contrast-Level Data

Contrast-level data (also referred to as contrast-synthesis data) consists of the relative effect estimates and their measures of precision for each pairwise comparison within a study [20]. This structure directly represents the comparisons between interventions rather than the absolute performance of individual arms. For binary outcomes, this typically includes log odds ratios, risk ratios, or hazard ratios with their standard errors and covariance structure for multi-arm trials [18] [20].

The contrast-level approach provides the foundation for contrast-synthesis models (CSMs), which combine the relative treatment effects across trials [19]. These models have intuitive appeal because they rely solely on within-study information and therefore respect the randomization within trials [19]. The Lu and Ades model is a prominent example of a CB model that requires a study-specific reference treatment to be defined in each study [18].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Arm-Level and Contrast-Level Data Structures

| Characteristic | Arm-Level Data | Contrast-Level Data |

|---|---|---|

| Basic unit | Raw summary measurements per treatment arm | Relative effect estimates between arms |

| Data examples | Number of events & participants (binary); means & SDs (continuous) | Log odds ratios, risk ratios, mean differences with standard errors |

| Model compatibility | Arm-synthesis models (ASMs) | Contrast-synthesis models (CSMs) |

| Information usage | Within-study and between-study information | Primarily within-study information |

| Respect for randomization | May compromise randomization in some implementations | Preserves randomization within trials |

| Range of estimands | Wider range (e.g., absolute effects, marginal risk differences) | Limited to relative effects |

Methodological Protocols for Data Extraction

Arm-Level Data Extraction Protocol

Application Context: This protocol is appropriate when planning to implement arm-synthesis models, when absolute effects or specific population-level estimands are of interest, or when working with sparse data where borrowing strength across arms is beneficial [21] [19].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Statistical software with Bayesian modeling capabilities (WinBUGS/OpenBUGS, JAGS, STAN)

- Data extraction template capturing arm-level details

- Bibliographic database (PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Central)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Identify outcome measures: Determine the primary and secondary outcomes of interest for data extraction, ensuring consistency in definitions across studies.

Extract arm-specific data:

- For binary outcomes: Record the number of events and total participants for each treatment arm within each study [20].

- For continuous outcomes: Record the mean, standard deviation (or standard error), and sample size for each treatment arm within each study.

- For time-to-event outcomes: Record the number of events, log hazard ratios, and their standard errors (though these represent contrasts, they are typically analyzed using arm-level models).

Document study characteristics: Extract additional study-level variables that may explain heterogeneity or effect modifiers, including:

- Study design features (randomization method, blinding)

- Population characteristics (age, disease severity, comorbidities)

- Treatment details (dose, duration, administration route)

Verify data consistency: Check for logical consistency within studies (e.g., total participants across arms should not exceed overall study population in parallel designs).

Format for analysis: Structure data with one row per study arm, including study identifier, treatment identifier, and outcome data.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the arm-level data extraction process:

Contrast-Level Data Extraction Protocol

Application Context: This protocol is appropriate when planning to implement contrast-synthesis models, when the research question focuses exclusively on relative treatment effects, or when incorporating studies that only report contrast data [18] [19].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Statistical software with network meta-analysis capabilities (R, WinBUGS, Stata)

- Data extraction template capturing contrast-level details

- Covariance matrix calculation tools for multi-arm trials

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Identify comparisons: Determine all pairwise comparisons available within each study.

Extract contrast data:

Select reference treatment: Designate a reference treatment for each study (often placebo or standard care) to maintain consistent direction of effects.

Document effect modifiers: Record study-level characteristics that may modify treatment effects, similar to the arm-level protocol.

Check consistency: Verify that contrast data is internally consistent, particularly for multi-arm trials where effects are correlated.

Format for analysis: Structure data with one row per contrast, including study identifier, compared treatments, effect estimate, and measure of precision.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the contrast-level data extraction process:

Bayesian MTC Modeling Considerations

Model Formulations

In Bayesian MTC, the choice between arm-level and contrast-level data structures leads to different model formulations with important implications for analysis and interpretation.

Arm-Synthesis Models (ASM) typically model the arm-level parameters directly. For a binary outcome with a logistic model, the probability of an event in arm (k) of study (i) ((p_{ik})) can be modeled as:

[ \text{logit}(p{ik}) = \mui + \delta_{i,bk} ]

where (\mui) represents the study-specific baseline effect (typically on the log-odds scale) for the reference treatment (b), and (\delta{i,bk}) represents the study-specific log-odds ratio of treatment (k) relative to treatment (b) [21]. The (\delta_{i,bk}) parameters are typically assumed to follow a common distribution:

[ \delta{i,bk} \sim N(d{bk}, \sigma^2) ]

where (d_{bk}) represents the mean relative effect of treatment (k) compared to (b), and (\sigma^2) represents the between-study heterogeneity [21].

Contrast-Synthesis Models (CSM) directly model the relative effects. The Lu and Ades model can be represented as:

[ \theta{ik}^a = \alpha{ibi}^a + \delta{ibik}^c \quad \text{for } k \in Ri ]

where (\theta{ik}^a) represents the parameter of interest in arm (k) of study (i), (\alpha{ibi}^a) represents the study-specific intercept for the baseline treatment (bi), and (\delta{ibik}^c) represents the relative effect of treatment (k) compared to (b_i) [18]. The relative effects are modeled as:

[ \delta{ibik}^c \sim N(\mu{1k}^c - \mu{1bi}^c, \sigmac^2) ]

where (\mu{1k}^c) represents the overall mean treatment effect for treatment (k) compared to the network reference treatment 1, and (\sigmac^2) represents the contrast heterogeneity variance [18].

Impact on Treatment Effect Estimates

Empirical evidence demonstrates that the choice between arm-level and contrast-level approaches can impact the resulting treatment effect estimates and rankings. A comprehensive evaluation of 118 networks with binary outcomes found important differences in estimates obtained from contrast-synthesis models (CSMs) and arm-synthesis models (ASMs) [19]. The different models can yield different estimates of odds ratios and standard errors, leading to differing surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) values that can impact the final ranking of treatment options [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Model Properties and Applications

| Property | Arm-Synthesis Models (ASM) | Contrast-Synthesis Models (CSM) |

|---|---|---|

| Model type | Hierarchical model on arm-level parameters | Hierarchical model on contrast parameters |

| Information usage | Within-study and between-study information | Primarily within-study information |

| Randomization | May compromise randomization | Respects randomization within trials |

| Missing data assumption | Arms missing at random | Contrasts missing at random |

| Heterogeneity modeling | Modeled on baseline risks and/or treatment effects | Modeled on relative treatment effects |

| Available estimands | Relative effects, absolute effects, marginal risk differences | Primarily relative effects |

| Implementation complexity | Generally more complex | Generally more straightforward |

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of Bayesian MTC analyses requires specific methodological tools and computational resources. The following table details essential research reagents for this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bayesian MTC Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | Bayesian analysis using MCMC | Historical standard for Bayesian MTC; user-friendly interface but limited development [21] |

| JAGS | Bayesian analysis using MCMC | Cross-platform alternative to BUGS; uses similar model specification [17] |

| STAN | Bayesian analysis using HMC | Modern platform with advanced sampling algorithms; requires different model specification [17] |

| R packages | Comprehensive statistical programming | Key packages: gemtc for MTC, pcnetmeta for Bayesian NMA, BUGSnet for comprehensive NMA [19] |

| ROBUST checklist | Quality assessment of Bayesian analyses | 7-item scale for assessing transparency and completeness of Bayesian reporting [17] |

| Vague priors | Default prior distributions | ( N(0, 10000) ) for location parameters; ( \text{Uniform}(0, 5) ) for heterogeneity parameters [21] |

| Consistency checks | Verification of direct/indirect evidence agreement | Node-splitting methods; design-by-treatment interaction test [21] [19] |

Case Study Application

To illustrate the practical implications of data structure choices, consider a Bayesian network meta-analysis of pharmacological treatments for alcohol dependence [21]. This network included direct comparisons between naltrexone (NAL), acamprosate (ACA), combination therapy (NAL+ACA), and placebo.

When implementing the analysis using contrast-level data with the Lu and Ades model [21], the researchers specified vague prior distributions for all parameters: ( N(0, 10000) ) for baseline and treatment effects, and ( \text{Uniform}(0, 5) ) for the common standard deviation. They assessed consistency between direct and indirect evidence using node-splitting methods and evaluated model convergence using trace plots and the Brooks-Gelman-Rubin statistic.

The analysis revealed that combination therapy (naltrexone+acamprosate) had the highest posterior probability of being the "best" treatment, a finding that was consistent across multiple outcomes [21]. This case demonstrates how Bayesian MTC with appropriate data structure selection can provide more precise estimates than pairwise meta-analysis alone, particularly for treatment comparisons with limited direct evidence.

The choice between arm-level and contrast-level data structures represents a fundamental methodological decision in Bayesian mixed treatment comparisons that significantly influences model specification, analysis, and interpretation. Arm-level data structures offer greater flexibility in the types of estimands that can be derived and may be particularly valuable when absolute effects or population-level summaries are of interest. Contrast-level data structures more directly respect randomization within trials and align with traditional meta-analytic approaches.

Empirical evidence from evaluations of real-world networks indicates that these approaches can yield meaningfully different results in practice, particularly for odds ratios, standard errors, and treatment rankings [19]. The characteristics of the evidence network, including its connectedness and the rarity of events, may influence the magnitude of these differences.

Researchers should carefully consider their research questions, the available data, and the desired estimands when selecting between these data structures. Pre-specification of the analytical approach in study protocols is recommended to maintain methodological rigor and transparency in Bayesian MTC research. As the use of Bayesian methods in medical research continues to grow at a notable pace, with a 12.3% compounded annual growth rate in surgical research specifically, proper understanding and application of these data structures becomes increasingly important for drug development professionals and clinical researchers [17].

Implementing Bayesian MTC Models: A Step-by-Step Workflow

In hierarchical models, often termed mixed-effects models, the distinction between fixed and random effects is fundamental. These models are widely used to analyze data with complex grouping structures, such as patients within hospitals or repeated measurements within individuals. The core difference lies not in the nature of the variables themselves, but in how their coefficients are estimated and interpreted [22].

Fixed effects are constant across individuals and are estimated independently without pooling information from other groups. In contrast, random effects are assumed to vary across groups and are estimated using partial pooling, where data from all groups inform the estimate for any single group. This allows groups with fewer data points to "borrow strength" from groups with more data, leading to more reliable and stable estimates, particularly for under-sampled groups [22] [23].

The following table summarizes the core differences:

Table 1: Core Differences Between Fixed and Random Effects

| Feature | Fixed Effects | Random Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | Maximum Likelihood (no pooling) | Partial Pooling / Shrinkage (BLUP) [23] |

| Goal of Inference | The specific levels in the data [23] | The underlying population of levels [23] |

| Information Sharing | No information shared between groups | Estimates for all groups inform each other |

| Generalization | Inference limited to observed levels | Can generalize to unobserved levels from the same population [23] |

| Degrees of Freedom | Uses one degree of freedom per level | Uses fewer degrees of freedom [23] |

Theoretical Foundations and Application Protocol

Conceptual Framework and Mathematical Formulation

The decision to designate an effect as fixed or random is often guided by the research question and the structure of the data. Statistician Andrew Gelman notes that the terms have multiple definitions, but a practical interpretation is that effects are fixed if they are of interest in themselves, and random if there is interest in the underlying population from which they were drawn [22].

A simple linear mixed-effects model can be formulated as follows [23]:

- Model Equation: ( yi = \alpha{j(i)} + \beta1 X{1i} + \beta2 X{2i} + \varepsilon_i )

- Random Effect: ( \alpha_j \sim \text{Normal}(\mu, \sigma^2) )

Here, ( yi ) is the response for observation ( i ), ( \alpha{j(i)} ) is the random intercept for the group ( j ) to which observation ( i ) belongs, ( \beta ) terms are fixed effect coefficients, and ( \varepsiloni ) is the residual error. The key is that the random effects ( \alphaj ) are assumed to be drawn from a common (usually Gaussian) distribution with mean ( \mu ) and variance ( \sigma^2 ), which is the essence of partial pooling [23].

Protocol for Defining the Model Structure

Objective: To correctly specify fixed and random effects in a hierarchical model based on the experimental design and research goals.

Procedure:

- Identify Grouping Structures: Determine the units of observation and the hierarchical or clustered structure of your data (e.g., patients within clinics, repeated measurements within subjects).

- Define the Research Goal for Each Factor:

- If the goal is to make inferences only about the specific levels included in your study (e.g., comparing three specific drug doses), model the factor as a fixed effect.

- If the goal is to make inferences about an underlying population of levels, and the levels in your study are a random sample from this population (e.g., selecting 10 clinics from a large pool of clinics nationwide), model the factor as a random effect.

- Assess Random Effects Suitability: For a factor to be a random effect, it should ideally have a sufficient number of levels to estimate the population variance reliably. A common guideline is to have at least five levels, though this is most critical when the variance of the random effect itself is of interest [23].

- Model Formulation: Write the model equation, clearly distinguishing fixed and random components. For instance, in a clinical trial with patients from multiple centers, the drug treatment would typically be a fixed effect, while the study center would be a random effect.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for specifying fixed and random effects in a hierarchical model.

Application in Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparisons (MTCs)

The Role of MTCs in Evidence Synthesis

In the context of drug development and systematic reviews, Mixed Treatment Comparisons (MTCs), also known as network meta-analyses, are a powerful extension of standard meta-analysis. They allow for the simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments (e.g., Drug A, Drug B, Drug C, Placebo) in a single, coherent statistical model, even when not all treatments have been directly compared in head-to-head trials [10] [24].