Addressing Heterogeneity in Network Meta-Analysis of Drugs: A Comprehensive Guide from Detection to Decision-Making

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address heterogeneity in network meta-analysis (NMA).

Addressing Heterogeneity in Network Meta-Analysis of Drugs: A Comprehensive Guide from Detection to Decision-Making

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address heterogeneity in network meta-analysis (NMA). Covering foundational concepts, methodological approaches, troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques, we explore the critical assumptions of transitivity and consistency, statistical measures (I², τ², Q), and advanced methods including network meta-regression and class-effect models. The guide emphasizes practical implementation using modern software tools and offers evidence-based strategies for robust interpretation and risk-averse clinical decision-making in the presence of heterogeneity.

Understanding Heterogeneity in NMA: Core Concepts, Sources, and Impact on Drug Evidence Synthesis

Frequently Asked Questions

What is heterogeneity in the context of a Network Meta-Analysis? In Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), heterogeneity refers to the variability in treatment effects between the individual studies included in the network. This variability goes beyond what would be expected from chance alone. It arises from differences in study populations, interventions, dosages, trial design, and outcome measurements across the trials. Assessing heterogeneity is crucial as it impacts the reliability and interpretation of the NMA results [1] [2].

Why is assessing heterogeneity so important for my NMA? Evaluating heterogeneity is fundamental to the validity of your NMA conclusions. Substantial heterogeneity can mean that the studies are not estimating a single common treatment effect, making a simple pooled estimate misleading. It can bias the NMA results and lead to incorrect rankings of treatments. Understanding the degree and sources of heterogeneity helps researchers decide if a random-effects model is appropriate, guides the exploration of reasons for variability through subgroup analysis or meta-regression, and provides context for how broadly the findings can be applied [1] [2].

What is the difference between heterogeneity and inconsistency? While sometimes used interchangeably, these terms have distinct meanings in NMA.

- Heterogeneity refers to differences in treatment effects within a single direct comparison (e.g., variability among all trials that compare Treatment A vs. Treatment B).

- Inconsistency refers to differences between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison within a network. For example, if the estimate from direct trials of A vs. C differs significantly from the estimate obtained by indirectly comparing A to C via a common comparator B, this is inconsistency. Special statistical tests, such as Higgins' global inconsistency test, are used to evaluate this [1] [3].

My NMA has high heterogeneity (I² > 50%). What should I do? A high I² value indicates substantial heterogeneity. Your troubleshooting steps should include:

- Verify Data and Model: Double-check your data for errors and ensure you are using an appropriate statistical model (e.g., a random-effects model).

- Explore Sources: Conduct subgroup analysis or meta-regression to investigate whether specific study-level covariates (e.g., patient baseline risk, publication year, trial design) can explain the variability.

- Assess Network Geometry: Examine the structure of your evidence network. Sparse networks or comparisons with few studies are more prone to heterogeneity.

- Consider Alternative Methods: If you have individual patient data for a subset of trials, using it can help account for heterogeneity. Advanced models like Jackson's random inconsistency model can also be considered.

- Report Transparently: Clearly report the heterogeneity statistics and discuss the potential implications for the robustness of your findings [1] [3] [2].

Statistical Measures of Heterogeneity: A Troubleshooting Guide

The table below summarizes the key statistical measures used to diagnose and quantify heterogeneity in meta-analyses.

Table 1: Key Statistical Measures for Heterogeneity Assessment

| Measure | What It Quantifies | Interpretation & Thresholds | Common Pitfalls & Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q Statistic [2] | Whether differences between study results are larger than expected by chance. | A significant p-value (<0.05) suggests the presence of heterogeneity. | Pitfall: Its power is low with few studies and oversensitive with many.Solution: Never interpret in isolation; use alongside I² and τ². |

| I² Statistic [2] | The percentage of total variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than chance. | 0-40%: might not be important; 30-60%: moderate; 50-90%: substantial; 75-100%: considerable. These are only rough guides. | Pitfall: Does not measure the actual magnitude of heterogeneity. A high I² can occur with precise studies even if absolute differences are small.Solution: Always report and interpret τ² alongside I². |

| τ² (tau-squared) [2] | The absolute magnitude of the variance of true treatment effects across studies. Reported in the same units as the effect size (e.g., log odds ratio). | A τ² of 0 indicates homogeneity. Larger values indicate greater dispersion of true effects. There are no universal thresholds; interpretation should be based on clinical context. | Pitfall: The default DerSimonian-Laird (DL) estimator is often biased.Solution: Use more robust estimators like Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) or Paule-Mandel. |

| Prediction Interval [2] | The expected range of true treatment effects in a future study or a specific setting, accounting for heterogeneity. | If a 95% prediction interval includes no effect (e.g., a risk ratio of 1), the treatment effect is inconsistent across study populations. | Pitfall: Often omitted from reports, giving a false sense of precision.Solution: Routinely calculate and report prediction intervals to better communicate the uncertainty in your findings. |

Methodologies for Investigating Heterogeneity

Protocol for Subgroup Analysis and Meta-Regression Subgroup analysis and meta-regression are used to explore whether study-level covariates explain heterogeneity [1].

- A Priori Planning: Pre-specify potential effect modifiers (e.g., mean patient age, disease severity, trial design, drug dose) in your study protocol to avoid data dredging.

- Data Extraction: Systematically extract data on the chosen covariates from each included study.

- Statistical Analysis:

- For subgroup analysis, stratify the network by the categorical covariate and perform separate NMAs within each stratum. Compare the treatment effects across strata.

- For meta-regression, incorporate the covariate directly into the NMA model. This tests if the covariate has a statistically significant interaction with treatment effects. The NMA package in R provides functions for this [3].

- Interpretation: Be cautious in interpreting findings, as these analyses are observational in nature. A significant association does not prove causation.

Protocol for Assessing Network Geometry The structure of the evidence network itself can influence heterogeneity. The following metrics, adapted from graph theory, help describe this geometry [4].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Describing Network Meta-Analysis Geometry

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Nodes | The total number of interventions being compared. | A higher number indicates a broader comparison but may increase complexity. |

| Number of Edges | The total number of direct comparisons available in the network. | More edges indicate more direct evidence is available. |

| Density | The number of existing connections divided by the number of possible connections. | Ranges from 0 to 1. Values closer to 1 indicate a highly connected, robust network. |

| Percentage of Common Comparators | The proportion of nodes that are directly linked to many other nodes (like a placebo). | A higher percentage indicates a more strongly connected network. |

| Median Thickness | The median number of studies per direct comparison (edge). | A higher value suggests more precise direct evidence for that comparison. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for NMA

Table 3: Key Software and Methodological Tools for NMA Heterogeneity Assessment

| Tool / Resource | Function | Use Case in Troubleshooting Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|

| R Package 'NMA' [3] | A comprehensive frequentist package for NMA based on multivariate meta-analysis models. | Performs network meta-regression, Higgins' global inconsistency test, and provides advanced inference methods. |

| Random-Effects Model [2] | A statistical model that assumes the true treatment effect varies across studies and estimates the distribution of these effects. | The standard model when heterogeneity is present. It incorporates the between-study variance τ² into the analysis. |

| Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) [2] | A method for estimating the between-study variance τ². | A robust alternative to the DerSimonian-Laird estimator; recommended for accurate quantification of heterogeneity. |

| Global Inconsistency Test [3] | A statistical test to check for disagreement between direct and indirect evidence in the entire network. | Used to validate the assumption of consistency, which is fundamental to a valid NMA. |

| Pesampator | Pesampator, CAS:1258963-59-5, MF:C18H20N2O4S2, MW:392.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PF-05020182 | PF-05020182, CAS:1354712-92-7, MF:C18H30N4O4, MW:366.46 | Chemical Reagent |

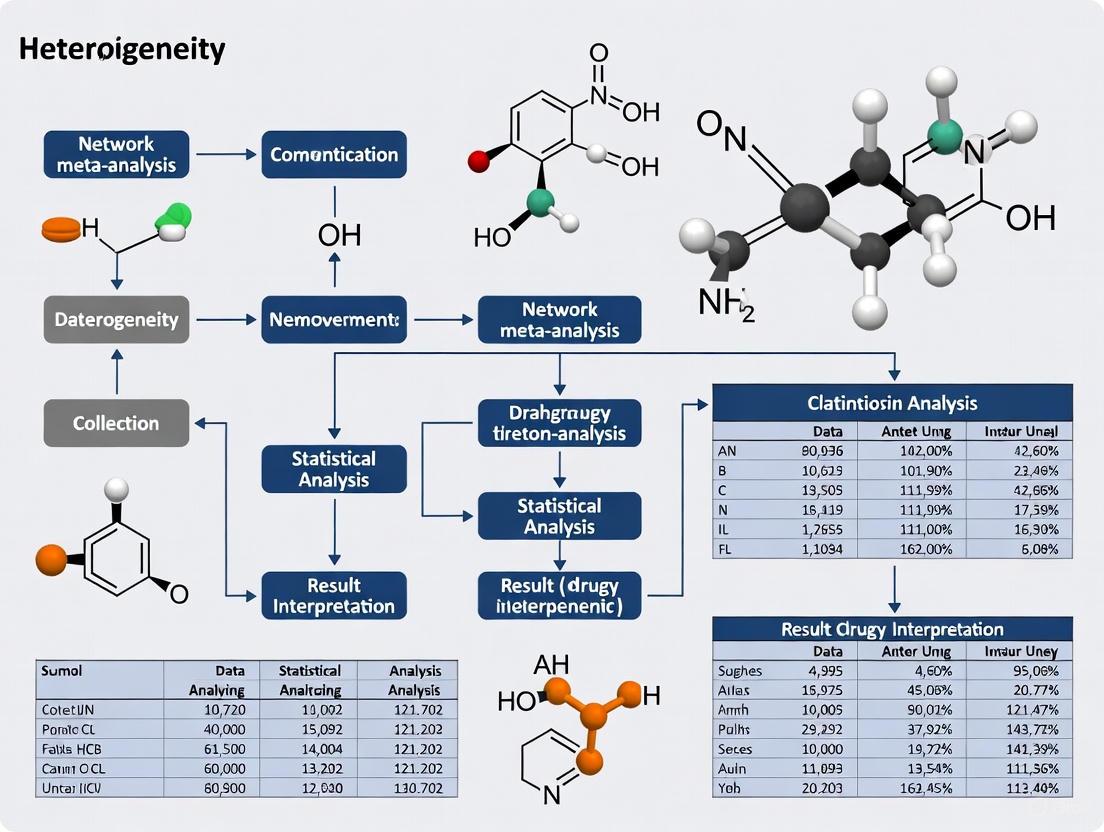

Workflow and Relationships Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing and addressing heterogeneity in a drug NMA.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

What are transitivity and consistency, and how do they differ? Transitivity and consistency are fundamental assumptions in Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), but they are assessed differently. Transitivity is a clinical and methodological assumption that must be evaluated before conducting the NMA. It posits that there are no systematic differences in the distribution of effect modifiers (e.g., patient demographics, disease severity) across the different treatment comparisons within the network [5] [6]. Essentially, the studies should be similar enough that the participants could hypothetically have been randomized to any of the interventions in the network [7]. Consistency is the statistical manifestation of transitivity. It refers to the agreement between direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) and indirect evidence (derived via a common comparator) for the same treatment comparison [7] [8]. While transitivity is conceptually assessed, consistency can be evaluated statistically once the NMA is performed [7].

What are the practical consequences of violating the transitivity assumption? Violating the transitivity assumption compromises the validity and credibility of the NMA results [5]. Since the benefits of randomization do not extend across different trials, systematic differences in effect modifiers can introduce confounding bias into the indirect and mixed treatment effect estimates [5] [8]. This can lead to incorrect conclusions about the relative effectiveness or harm of the interventions, potentially misinforming clinical decisions and health policies [7].

My network is star-shaped (all trials compare other treatments to a single common comparator, like a placebo). Can I check for transitivity? Yes, you must still evaluate transitivity. A star-shaped network precludes the evaluation of statistical consistency because there are no closed loops to compare direct and indirect evidence [5]. However, the assessment of transitivity—scrutinizing the distribution of effect modifiers across the different treatment-versus-placebo comparisons—remains critically important for the validity of your indirect comparisons [5] [6].

I have identified potential intransitivity in my network. What are my options? If transitivity is questionable, you have several options [5]:

- Network Meta-Regression: Use this to adjust for the effect modifiers causing the imbalance, provided you have a sufficient number of trials [5] [6].

- Subnetworks: Split the network into smaller, more homogenous subnetworks where the transitivity assumption is more plausible [5].

- Refrain from NMA: If the concerns are severe and cannot be adjusted for, it may not be valid or feasible to perform an NMA [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Incoherence (Inconsistency) is Detected in a Network Loop

Issue: Statistical tests indicate a significant disagreement between the direct and indirect evidence for one or more treatment comparisons.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

Step 1: Verify Data Extraction and Analysis

- Double-check the data entered into your statistical model for accuracy.

- Ensure that multi-arm trials have been correctly handled in the analysis to preserve within-trial randomization [8].

Step 2: Conduct a Local Inspection

- Use the node-splitting method to isolate the inconsistent comparison. This method separates the direct and indirect evidence for a specific node (treatment) and estimates the difference between them [7].

Step 3: Investigate Conceptual Causes

- Incoherence is often a sign of a violation of the transitivity assumption. Return to the conceptual evaluation of transitivity [8]. Use the following table to guide your investigation of potential effect modifiers:

Table: Checklist for Investigating Sources of Intransitivity

Investigation Area Key Questions to Ask Common Effect Modifiers Population Is the patient population comparable across comparisons? Are there differences in disease severity, duration, or demographic profiles? Disease duration, baseline severity, age, sex, comorbidities [6]. Intervention Are the interventions administered in a similar way? Is the dose or delivery method comparable? Dosage, formulation, treatment duration, concomitant therapies [6]. Study Methods Do the trials informing different comparisons have similar designs and risk of bias? Risk of bias items (e.g., randomization, blinding), study duration, outcome definitions [6] [8]. Step 4: Implement a Solution

- Based on your findings from Step 3, you can:

- Perform a meta-regression to adjust for the identified effect modifier.

- Use a network meta-regression model if the effect modifier is measured at the study level [5] [6].

- Consider presenting results for subgroups if the transitivity violation is limited to a specific patient population or intervention type.

- Based on your findings from Step 3, you can:

Problem: Evaluating Transitivity with Many Potential Effect Modifiers

Issue: It is challenging to visually or statistically assess the distribution of numerous clinical and methodological characteristics across all treatment comparisons.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

Step 1: Identify and Prioritize Effect Modifiers

Step 2: Calculate Dissimilarity Between Comparisons

- Adopt a novel methodological approach that uses Gower's Dissimilarity Coefficient [6]. This metric calculates the overall dissimilarity between pairs of studies (and by extension, between treatment comparisons) based on a mix of quantitative (e.g., mean age) and qualitative (e.g., concomitant medication use) characteristics [6].

- The result is a dissimilarity matrix that quantifies the clinical and methodological heterogeneity within the network.

Step 3: Apply Hierarchical Clustering

- Use the dissimilarity matrix to perform hierarchical clustering [6]. This unsupervised learning method groups highly similar treatment comparisons into clusters while separating dissimilar ones.

- Visualize the results using a dendrogram and heatmap. This helps identify "hot spots" of potential intransitivity where certain comparisons cluster separately from others, warranting closer scrutiny [6].

Step 4: Interpret and Act on Findings

- The clustering pattern provides a semi-objective judgment on the plausibility of transitivity. If studies are organized into several distinct clusters based on key characteristics, this suggests potential intransitivity [6].

- This finding necessitates a closer examination of the evidence base to decide if NMA is feasible or if adjustments are needed [6].

Data Presentation

Table: Reporting and Evaluation of Transitivity Before and After PRISMA-NMA Guidelines (Survey of 721 NMAs) [5]

| Reporting and Evaluation Item | Before PRISMA-NMA (%) | After PRISMA-NMA (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provided a protocol | -- | -- | 3.94 (2.79–5.64) |

| Pre-planned transitivity evaluation | -- | -- | 3.01 (1.54–6.23) |

| Reported the evaluation and results | -- | -- | 2.10 (1.55–2.86) |

| Defined transitivity | -- | -- | 0.57 (0.42–0.79) |

| Discussed implications of transitivity | -- | -- | 0.48 (0.27–0.85) |

| Evaluated transitivity statistically | 40% | 54% | -- |

| Evaluated transitivity conceptually | 12% | 11% | -- |

| Used consistency evaluation | 34% | 47% | -- |

| Inferred plausibility of transitivity | 22% | 18% | -- |

Experimental Protocol: A Framework for Evaluating Transitivity

Objective: To conceptually and empirically evaluate the transitivity assumption in a network meta-analysis.

Methodology: This protocol outlines a step-by-step process for a thorough transitivity assessment, integrating both traditional and novel methods.

Pre-specification in Protocol:

- State the transitivity assumption in the systematic review protocol.

- Pre-plan the evaluation methods and list all potential effect modifiers justified by clinical or methodological reasoning [5].

Data Collection:

- From each included study, extract a common set of participant and study characteristics that are suspected effect modifiers. These can be quantitative (e.g., mean age, disease duration) or qualitative (e.g., prior treatment failure, study design feature) [6].

Conceptual Evaluation:

- Tabulate or Visualize: Create summary tables, bar plots, or box plots to show the distribution of each effect modifier across the different treatment comparisons [6].

- Assess Comparability: Judge whether the distributions are sufficiently similar across comparisons. This relies on subjective judgment informed by clinical expertise [5] [8].

Empirical Evaluation using Clustering (Optional but Recommended):

- Calculate Dissimilarity: Use Gower's Dissimilarity Coefficient to compute a dissimilarity matrix for all study pairs across the extracted characteristics [6].

- Perform Clustering: Apply hierarchical clustering to the dissimilarity matrix.

- Visualize and Interpret: Generate a dendrogram and heatmap. Examine if studies cluster by treatment comparison rather than being intermingled, which would signal potential intransitivity [6].

Conclusion and Reporting:

- Based on the conceptual and empirical evaluations, make an overall judgment on the plausibility of transitivity.

- Justify the conclusion in the review report, citing the comparability of trials and/or the results of any statistical or clustering evaluations [5].

Logical Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Methodological Tools for Transitivity and Consistency Evaluation

| Tool / Method | Function in NMA | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gower's Dissimilarity Coefficient [6] | Quantifies the overall dissimilarity between two studies across multiple mixed-type (numeric and categorical) characteristics. | Handles missing data by considering only characteristics reported in both studies. Essential for the clustering approach. |

| Hierarchical Clustering [6] | An unsupervised machine learning method that groups similar treatment comparisons based on their characteristics. Identifies potential "hot spots" of intransitivity. | Results are exploratory. The choice of the optimal number of clusters may require subjective judgment supplemented by validity measures. |

| Node-Splitting Method [7] | A statistical technique used to detect local inconsistency. It separates direct and indirect evidence for a specific comparison and tests if they disagree. | Useful for pin-pointing which specific loop in the network is inconsistent. Requires a closed loop in the network. |

| Network Meta-Regression [5] [6] | Adjusts treatment effect estimates for study-level covariates (effect modifiers). Can help mitigate confounding bias if transitivity is questionable. | Requires a sufficient number of studies to be informative. Power is often low in sparse networks. |

| PRISMA-NMA Checklist [5] | A reporting guideline that ensures transparent and complete reporting of NMA methods and results, including the assessment of transitivity and consistency. | Following the checklist improves the review's credibility. Systematic reviews published after PRISMA-NMA show better reporting in some aspects [5]. |

| PF-06685249 | `PF-06685249|LPA Receptor Antagonist|Research Use Only` | PF-06685249 is a potent LPA receptor antagonist for research. This product is For Research Use Only and not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Pralidoxime Iodide | Pralidoxime Iodide | Pralidoxime iodide is a research-grade oxime for studying organophosphate poisoning mechanisms. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

FAQs on Core Heterogeneity Concepts

Q1: What do the Q, I², and τ² statistics each tell me about my meta-analysis? These three statistics provide complementary information about the variability between studies in your meta-analysis.

- Q statistic (Cochran's Q): This is a test statistic that assesses whether the observed differences in study results are larger than would be expected by chance alone. A significant p-value (typically <0.05) suggests the presence of genuine heterogeneity [9] [2].

- I² statistic: This quantifies the proportion of total variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). It is expressed as a percentage. For example, an I² of 75% means that 75% of the total variation across studies is attributable to real differences in effect sizes [9] [10].

- τ² statistic (Tau-squared): This quantifies the absolute magnitude of the between-study variance. It is measured in the same units as your effect size (e.g., log odds ratio, mean difference), providing a direct measure of the dispersion of true effects [2] [10].

Q2: How should I interpret different I² values in my drug efficacy analysis? While I² should not be interpreted using rigid thresholds, the following guidelines are commonly used as a rule of thumb [10]:

- I² = 25%: Considered low heterogeneity.

- I² = 50%: Considered moderate heterogeneity.

- I² = 75%: Considered substantial heterogeneity. Important Caveat: I² can be unreliable when the number of studies or the number of events in studies is small. It also depends on the precision of the included studies. Always consider the confidence interval for I² and the clinical context of the observed variation [11].

Q3: My meta-analysis has few studies. Are my heterogeneity statistics reliable? Meta-analyses with a limited number of studies pose challenges for interpreting heterogeneity. With few studies, the Q statistic has low power to detect heterogeneity, which may lead to an underestimation of true variability [9] [11]. The I² statistic can be unstable and imprecise. One empirical study suggested that estimates may fluctuate until a meta-analysis includes approximately 500 events and 14 trials [11]. It is therefore crucial to report and consider the confidence intervals for I² in such situations, as they better reflect the underlying uncertainty [11].

Q4: When should I use a random-effects model instead of a fixed-effect model? The choice of model depends on your assumptions about the studies included.

- Use a fixed-effect model only if you believe all studies are estimating a single, common effect size, and that any observed differences are solely due to sampling error [9] [2].

- Use a random-effects model if you believe that the true effect size can vary from study to study due to differences in populations, interventions, or other factors. The random-effects model explicitly incorporates the between-study variance τ² into its calculations and is often considered a more natural choice in medical and drug development contexts [9] [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High and Significant Q Statistic

Problem: Your analysis yields a Cochran's Q statistic with a significant p-value, indicating substantial variability between studies.

Diagnosis and Interpretation:

- A significant Q statistic confirms that heterogeneity exists beyond sampling error [2]. The next step is to quantify and interpret this heterogeneity using I² and τ².

Recommended Actions:

- Quantify the Heterogeneity: Calculate I² to understand the proportion of total variability due to heterogeneity, and τ² to understand its absolute magnitude [2] [10].

- Investigate Sources: Do not stop at the statistics. Perform subgroup analyses or meta-regressions to explore potential clinical or methodological sources of the heterogeneity (e.g., drug dosage, patient demographics, study risk of bias) [2].

- Report Appropriately: Always present the estimates of τ² and I² alongside the Q statistic and its p-value to give a complete picture of the heterogeneity [2] [10].

Issue 2: High I² Value

Problem: Your meta-analysis shows a high I² value (e.g., >75%), suggesting a large proportion of the variability is due to heterogeneity.

Diagnosis and Interpretation:

- A high I² indicates that the percentage of variability from heterogeneity is high [10]. However, it does not inform you about the magnitude or clinical importance of this heterogeneity. A high I² can occur even with small, clinically irrelevant differences if the included studies are very precise (e.g., have large sample sizes) [10].

Recommended Actions:

- Check τ²: Examine the τ² value. A high I² with a small τ² may indicate that the absolute magnitude of heterogeneity is not clinically worrisome, despite being a large proportion of the total variation.

- Consider the Clinical Relevance: Judge whether the predicted range of effects, perhaps visualized using a prediction interval, includes clinically important differences [2].

- Avoid Over-reliance: Do not use I² in isolation. It should be interpreted alongside τ² and the clinical context of the analyzed outcome [2] [10].

Issue 3: Choosing an Estimator for τ²

Problem: You are unsure which statistical estimator to use for calculating the between-study variance τ² in a random-effects model.

Diagnosis and Interpretation:

- The choice of estimator can impact the pooled estimate and its confidence interval, especially when the number of studies is small [2].

Recommended Actions:

- Prefer Advanced Estimators: The DerSimonian-Laird (DL) estimator is historically common but is known to be biased, particularly with few studies or high heterogeneity. It is no longer recommended as the default [2].

- Use Modern Defaults: Opt for the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) or Paule-Mandel estimators, which are generally less biased and are now considered standard for frequentist meta-analysis [2].

- Consider Bayesian Methods: For complex models like network meta-analyses or when dealing with very sparse data, Bayesian methods can be a flexible alternative, allowing you to incorporate prior knowledge about the heterogeneity [2].

Key Statistical Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Calculating Heterogeneity Statistics

This protocol outlines the standard methodology for deriving key heterogeneity measures from your meta-analysis data [10].

Formula:

- Cochran's Q: ( Q = \sum\limits{k=1}^K wk (\hat\thetak - \frac{\sum\limits{k=1}^K wk \hat\thetak}{\sum\limits{k=1}^K wk})^{2} ) Where (k) is an individual study, (K) is the total number of studies, (\hat\thetak) is the effect estimate of study (k), and (wk) is the weight (typically the inverse of the variance) of study (k).

- I² Statistic: (I^{2} = max \left{0, \frac{Q-(K-1)}{Q} \right})

- τ² Statistic: Several estimators exist (see Troubleshooting Guide, Issue 3). The DerSimonian-Laird estimator is: ( \tau^{2} = \frac{Q - (K-1)}{\sum wi - \frac{\sum wi^2}{\sum w_i}} )

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Applying a Random-Effects Model

This protocol details the steps for pooling studies using a random-effects model, which accounts for heterogeneity via τ².

Formula: The weight assigned to each study in a random-effects model is ( wk^* = 1 / (vk + \tau^2) ), where (vk) is the within-study variance for study (k) and (\tau^2) is the estimated between-study variance. The pooled effect is then: ( \theta^* = \frac{\sum wk^* \thetak}{\sum wk^*} )

Workflow Diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions: Statistical Toolkit

Table: Essential Components for Heterogeneity Analysis in Meta-Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cochran's Q Statistic | A hypothesis test to determine if observed heterogeneity is statistically significant [2]. | Low power with few studies; high power with many studies, which may flag trivial differences as significant [9] [2]. |

| I² Statistic | Describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance [9] [10]. | Can be misinterpreted; a high value does not necessarily mean the heterogeneity is clinically important, especially with high-precision studies [10]. |

| τ² (Tau-squared) | Quantifies the actual magnitude of between-study variance in the units of the effect measure [2]. | Choosing an unbiased estimator (e.g., REML) is critical for accurate results, particularly when the number of studies is small [2]. |

| Prediction Interval | A range in which the true effect of a new, similar study is expected to lie, providing a more useful clinical interpretation of τ² [2]. | Directly communicates the implications of heterogeneity for practice and future research [2]. |

| Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) | A preferred method for estimating τ² that is less biased than the older DerSimonian-Laird method [2]. | Now considered a standard approach for frequentist random-effects meta-analysis [2]. |

| Propargyl-PEG5-amine | Propargyl-PEG5-amine, MF:C13H25NO5, MW:275.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Propargyl-PEG6-acid | Propargyl-PEG6-acid, MF:C16H28O8, MW:348.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In Network Meta-Analysis (NMA), network geometry refers to the structure and arrangement of connections between different treatments based on the available clinical trials. This geometry is not merely a visual aid; it fundamentally shapes how evidence flows through the network and directly influences the statistical heterogeneity—the variation in treatment effects across studies. Understanding this relationship is crucial for interpreting NMA results reliably, especially in drug research where multiple treatment options exist.

The geometry of an evidence network reveals potential biases in the research landscape. Certain treatments may be extensively compared against placebos but rarely against each other, creating "star-shaped" networks. This imbalance can affect the confidence in both direct and indirect evidence, subsequently impacting heterogeneity. This technical support guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice to help researchers diagnose and address geometry-related heterogeneity issues in their NMA projects.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How can I visually assess if my network's geometry might be causing heterogeneity?

- Problem: You suspect the structure of your evidence network is contributing to inconsistent results.

- Solution: Begin by creating and critically examining a network diagram. Look for imbalances, such as:

- Star-shaped networks: Where one treatment (often a placebo or standard care) is the sole connector for many other treatments.

- Thick and thin lines: Comparisons with many trials (thick lines) will have more robust direct evidence, while those with single trials (thin lines) rely more heavily on the transitivity assumption.

- Disconnected networks: Isolated groups of treatments with no connecting path, which prevent some comparisons altogether. The diagram below illustrates a sample network geometry, highlighting key features like closed loops and evidence thickness.

Sample Network Geometry Showing Evidence Flow

FAQ 2: My inconsistency tests are significant. How do I determine which comparison is the culprit?

- Problem: Statistical tests indicate a significant disagreement between direct and indirect evidence in your network (a lack of coherence) [12].

- Solution:

- Identify Closed Loops: Use your network diagram to find all closed loops of evidence (e.g., where treatments A, B, and C have been compared in a triangle: A vs. B, B vs. C, and A vs. C) [12].

- Separate Direct and Indirect Evidence: For each loop, statistically separate the direct evidence (from head-to-head trials) from the indirect evidence (inferred via the common comparator).

- Use Node-Splitting Models: Employ statistical methods like node-splitting to test for inconsistency in each specific loop. This helps pinpoint exactly which direct comparison is in conflict with the rest of the network [12].

FAQ 3: The treatments in my network seem too diverse. How do I evaluate the transitivity assumption?

- Problem: You are concerned that clinical or methodological differences between trials (e.g., in patient population, dose, or study duration) violate the transitivity assumption, leading to heterogeneity [12].

- Solution:

- Create Subnetworks: Group trials that are more clinically homogeneous (e.g., only studies with severe disease, or only studies using a high drug dose).

- Compare Effects: Conduct separate NMAs on these subnetworks. If the treatment effect estimates differ significantly between subnetworks, transitivity may be violated, and the overall NMA may be unreliable.

- Use Meta-Regression: Statistically model whether study-level covariates (like disease severity or publication year) explain the heterogeneity in the network.

FAQ 4: How can I effectively visualize results from a complex NMA with many outcomes?

- Problem: Presenting results for multiple treatments across multiple outcomes is challenging.

- Solution: Consider using advanced graphical tools like the Kilim plot [13]. This plot compactly summarizes results for all treatments and outcomes, displaying absolute effects (e.g., event rates) rather than relative effects. Cells within the plot can be color-coded to represent the strength of statistical evidence, making it easier to identify treatments that perform well or poorly across the board.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Heterogeneity

Protocol for Testing Local Incoherence via Node-Splitting

Objective: To identify specific comparisons within the network where direct and indirect evidence are inconsistent.

Materials: Statistical software with NMA capabilities (e.g., R with netmeta or gemtc packages, Stata with network suite).

Methodology:

- Model Specification: Fit a node-splitting model to your network. This model separately estimates the effect size for a specific comparison using both its direct evidence and its indirect evidence from all other paths in the network.

- Iteration: Run the model for every possible treatment comparison that forms a closed loop in the network.

- Statistical Testing: For each comparison, the model will provide a p-value for the difference between the direct and indirect estimate.

- Interpretation: A statistically significant p-value (e.g., < 0.05) indicates local incoherence for that particular comparison. This suggests that the specific loop contributing to that comparison may be a major source of overall heterogeneity.

Protocol for Visualizing Complex Component NMA (CNMA) Structures

Objective: To clearly visualize the data structure of a Component NMA, where interventions are broken down into their individual components, which is often complex and prone to heterogeneity.

Materials: R or Python for generating specialized plots.

Methodology:

- Data Structuring: Organize your arm-level data to indicate which components are present in each intervention arm of each trial [14].

- Plot Selection: Based on your needs, generate one or more of the following novel CNMA visualizations [14]:

- CNMA-UpSet Plot: Ideal for networks with a large number of components, this plot effectively shows which combinations of components have been tested and how many trials contribute evidence for each combination.

- CNMA Heat Map: A grid where rows are components and columns are trials. This illustrates the distribution of components across the evidence base, revealing which components are commonly studied together or in isolation.

- CNMA-Circle Plot: Visualizes the combinations of components that differ between trial arms, helping to understand the direct evidence for additive or interactive effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key methodological tools and concepts essential for diagnosing and managing heterogeneity in NMA.

| Tool/Concept | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Network Diagram | A visual map of the evidence. It uses nodes (treatments) and lines/edges (direct comparisons). The thickness of lines and size of nodes often represent the amount of evidence, immediately highlighting potential imbalances in the network geometry [12]. |

| Transitivity Assessment | The theoretical foundation of NMA. It is the assumption that the included trials are sufficiently similar in their clinical and methodological characteristics (e.g., patient populations, outcomes) to allow for valid indirect comparisons. Violations cause heterogeneity [12]. |

| Statistical Incoherence | The statistical manifestation of transitivity violation. It is a measurable disagreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same treatment comparison. Tools like node-splitting and design-by-treatment interaction models are used to test for it [12]. |

| Component NMA (CNMA) Models | A modeling approach that estimates the effect of individual intervention components (e.g., 'behavioral therapy,' 'drug dose') rather than whole interventions. This can help reduce heterogeneity and uncertainty by pooling evidence more efficiently across different combinations of components [14]. |

| Kilim Plot | A graphical tool for visualizing NMA results on multiple outcomes simultaneously. It presents results as absolute effects (e.g., event rates) and uses color to represent the strength of statistical evidence, aiding in the interpretation of complex results and identification of heterogeneity patterns across outcomes [13]. |

| Propargyl-PEG6-N3 | Propargyl-PEG6-N3, MF:C15H27N3O6, MW:345.39 g/mol |

| Nesolicaftor | Nesolicaftor, CAS:1953130-87-4, MF:C18H18N4O4, MW:354.4 g/mol |

Visualizing Evidence Flow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for troubleshooting heterogeneity, linking diagnostic questions to analytical techniques and potential solutions.

Heterogeneity Troubleshooting Workflow

Network meta-analysis (NMA) is an advanced statistical technique that compares three or more interventions simultaneously by combining both direct and indirect evidence across a network of studies [8]. Unlike conventional pairwise meta-analyses that are limited to direct comparisons, NMA enables researchers to estimate relative treatment effects even between interventions that have never been directly compared in clinical trials [15] [7]. This approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research where multiple competing interventions often exist for a single condition, and conducting a "mega-RCT" comparing all treatments is practically impossible [7].

Heterogeneity refers to the variability in study characteristics and results, and represents a fundamental challenge in NMA. Properly understanding, assessing, and managing heterogeneity is crucial for producing valid and reliable results that can inform clinical decision-making and health policy [16] [7]. Heterogeneity in NMA can be categorized into three main types: clinical heterogeneity (variability in participants, interventions, and outcomes), methodological heterogeneity (variability in study design and risk of bias), and statistical heterogeneity (variability in the intervention effects being evaluated across studies) [16].

Core Concepts and Terminology

Key NMA Terminology

Direct Evidence: Comparison of two or more interventions within individual studies [7].

Indirect Evidence: Comparisons between interventions made through one or more common comparators [8] [7]. For example, if intervention A has been compared to B, and A has also been compared to C, then B and C can be indirectly compared through their common comparator A [8].

Transitivity: The assumption that different sets of randomized trials are similar, on average, in all important factors other than the intervention comparison being made [8]. This requires that studies comparing different interventions are sufficiently similar in terms of effect modifiers [8].

Consistency (Coherence): The statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence for the same comparison [8] [7]. Incoherence occurs when different sources of information about a particular intervention comparison disagree [8].

Network Geometry and Visualization

A network diagram graphically depicts the structure of a network of interventions, consisting of nodes representing interventions and lines showing available direct comparisons between them [8]. The geometry of the network reveals important information about the available evidence:

- Closed Loop: Exists when both direct and indirect comparisons are available for a treatment pair [7].

- Open Triangle: Exists when the shape formed by direct comparisons is incomplete [7].

- Network Connectivity: All included studies must be connected to allow comparisons across all interventions [7].

Network Geometry Showing Direct and Indirect Comparisons

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Managing Heterogeneity

Clinical Heterogeneity

Problem: Variability in participant characteristics, intervention implementations, or outcome measurements across studies introduces clinical heterogeneity that may compromise transitivity assumptions [16].

Symptoms:

- Significant statistical heterogeneity (I² > 50%) in pairwise meta-analyses

- Incoherence between direct and indirect evidence

- Differing patient case-mix across treatment comparisons

- Variable intervention fidelity or delivery methods

Solutions:

- Stratified Randomization: In primary trials, stratify randomization on center and key prognostic factors to prevent imbalance [16].

- Relax Selection Criteria: Use minimal exclusion criteria to better represent the target population [16].

- Account for Center Effects: Use random-effects models that better accommodate between-center heterogeneity [16].

- Subgroup Analysis Limitation: Limit subgroup analyses to those that meaningfully inform clinical decision-making [16].

Methodological Heterogeneity

Problem: Variability in study designs, risk of bias, or outcome assessment methods introduces methodological heterogeneity that can affect treatment effect estimates [16].

Symptoms:

- Differing randomization or blinding procedures across studies

- Variable follow-up durations

- Inconsistent outcome measurement tools or timing

- Differential application of eligibility criteria across centers

Solutions:

- Comprehensive Risk of Bias Assessment: Use standardized tools (e.g., Cochrane RoB 2.0) to evaluate all included studies.

- Sensitivity Analyses: Exclude studies with high risk of bias to assess their impact on overall estimates.

- Standardized Outcome Definitions: Where possible, use objective outcomes that are routinely collected in clinical practice [16].

- Meta-regression: Explore whether methodological features explain heterogeneity in treatment effects.

Statistical Heterogeneity and Incoherence

Problem: Discrepancies between direct and indirect evidence (incoherence) threaten the validity of NMA results [8] [7].

Symptoms:

- Significant disagreement between direct and indirect estimates for the same comparison

- Incoherence P-values < 0.05 in statistical tests

- Inconsistent treatment rankings across different outcome measures

Solutions:

- Local Incoherence Assessment: Use node-splitting methods to evaluate inconsistency at specific treatment comparisons.

- Global Incoherence Assessment: Employ design-by-treatment interaction models to assess overall network consistency.

- Use Higher Certainty Evidence: When incoherence exists, prioritize evidence from direct comparisons with higher certainty [15].

- Investigate Effect Modifiers: Explore clinical or methodological differences that might explain the observed incoherence.

Table 1: Common Sources of Heterogeneity in Pharmaceutical NMAs

| Source Category | Specific Sources | Impact on NMA | Management Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Age, disease severity, comorbidities, genetic factors, socioeconomic status | Affects treatment response and generalizability | Relax selection criteria [16], adjust for prognostic factors, subgroup analyses |

| Intervention Factors | Dosage, administration route, treatment duration, concomitant medications | Alters effective treatment intensity and safety | Dose-response meta-analysis, class-effect models, treatment adherence assessment |

| Methodological Elements | Randomization methods, blinding, outcome assessment, follow-up duration | Introduces bias varying across comparisons | Risk of bias assessment, sensitivity analyses, meta-regression [16] |

| Setting-related Factors | Care setting (primary vs. tertiary), geographical region, healthcare system | Affects implementation and effectiveness | Center stratification [16], random-effects models, contextual factor analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Heterogeneity Assessment

Transitivity Assessment Protocol

Purpose: To evaluate whether the transitivity assumption is reasonable for the network of studies.

Materials: Comprehensive dataset of included studies with detailed characteristics.

Procedure:

- List all potential effect modifiers relevant to the research question.

- Create a table comparing the distribution of these effect modifiers across different treatment comparisons.

- Assess whether studies comparing different interventions are sufficiently similar in terms of these effect modifiers.

- Qualitatively judge whether transitivity assumption is plausible.

- Document any potential violations of transitivity that might explain future incoherence.

Interpretation: If important effect modifiers are imbalanced across treatment comparisons, the transitivity assumption may be violated, and NMA results should be interpreted with caution.

Incoherence Evaluation Protocol

Purpose: To statistically assess agreement between direct and indirect evidence.

Materials: Network dataset with direct and indirect evidence sources.

Procedure:

- Local Incoherence Assessment:

- Use node-splitting method to separate direct and indirect evidence for each comparison.

- Test for statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between direct and indirect estimates.

- Apply appropriate multiple testing corrections.

- Global Incoherence Assessment:

- Fit both consistency and inconsistency models.

- Use likelihood ratio test or Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) to compare model fit.

- If inconsistency model fits better, identify specific comparisons contributing to incoherence.

- Investigate Sources: Explore clinical or methodological differences that might explain identified incoherence.

Interpretation: Significant incoherence suggests violation of transitivity assumption and may limit the validity of NMA results.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How much heterogeneity is acceptable in an NMA?

There are no universally accepted thresholds for acceptable heterogeneity in NMA. The impact depends on the research context and the magnitude of treatment effects. Rather than focusing solely on statistical measures, consider whether heterogeneity affects the conclusions and clinical applicability of results. The key question is whether heterogeneity prevents meaningful conclusions that can inform clinical decision-making.

Q2: What should I do when I detect significant incoherence between direct and indirect evidence?

When incoherence is detected: (1) Present both direct and indirect estimates separately rather than the combined network estimate; (2) If the direct evidence has higher certainty, prioritize it over the network estimate [15]; (3) Investigate potential effect modifiers that might explain the discrepancy through subgroup analysis or meta-regression; (4) Acknowledge the uncertainty in your conclusions and consider presenting alternative analyses.

Q3: How can I plan a primary trial to facilitate future inclusion in NMAs?

To enhance future NMA compatibility: (1) Select comparators that are relevant to clinical practice, not just placebos; (2) Use standardized outcome measures consistent with other trials in the field; (3) Report detailed patient characteristics and potential effect modifiers; (4) Follow CONSORT reporting guidelines; (5) Consider using core outcome sets where available.

Q4: What are the most common mistakes in assessing and reporting heterogeneity in NMAs?

Common mistakes include: (1) Focusing only on statistical heterogeneity without considering clinical relevance; (2) Not adequately assessing transitivity assumption before conducting NMA; (3) Overinterpreting treatment rankings without considering uncertainty; (4) Using inappropriate heterogeneity measures (e.g., applying pairwise I² to network estimates); (5) Not conducting or properly reporting sensitivity analyses for heterogeneous findings.

Research Reagent Solutions: Methodological Tools

Table 2: Essential Methodological Tools for Heterogeneity Assessment in NMA

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (netmeta, gemtc packages), Stata, WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | Perform NMA statistical calculations | Bayesian and frequentist NMA implementation [7] |

| Heterogeneity Measurement | I² statistic, between-study variance (τ²), predictive intervals | Quantify statistical heterogeneity | Assessing variability in treatment effects across studies |

| Incoherence Detection | Node-splitting, design-by-treatment interaction test, side-splitting method | Identify discrepancies between direct and indirect evidence | Evaluating NMA validity assumptions [8] [7] |

| Risk of Bias Assessment | Cochrane RoB 2.0, ROBINS-I | Evaluate methodological quality of included studies | Identifying methodological heterogeneity sources [16] |

| Visualization Tools | Network diagrams, forest plots, rankograms, contribution plots | Visual representation of evidence network and results | Communicating NMA structure and findings clearly [8] |

Advanced Methodologies: Emerging Approaches

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) are gaining regulatory momentum and represent a pivotal shift in how drug candidates are evaluated [17]. These include in vitro systems (3D cell cultures, organoids, organ-on-chip) and in silico approaches that can reduce animal testing while providing human-relevant mechanistic data [17].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with NMA offers promising approaches for handling heterogeneity: AI/ML can help distinguish signal from noise in biological data, reduce data dimensionality, and automate the comparison of alternative mechanistic models [17]. These approaches are particularly valuable for translating high-dimensional phenotypic data into clinically meaningful predictions.

NMA Heterogeneity Assessment Workflow

Effectively managing heterogeneity in pharmaceutical NMAs requires a systematic approach throughout the research process. Key best practices include:

- Proactive Planning: Consider NMA compatibility when designing primary trials and systematic review protocols.

- Comprehensive Assessment: Evaluate transitivity before conducting NMA and test for incoherence after analysis.

- Appropriate Interpretation: Consider both statistical measures and clinical relevance when interpreting heterogeneous results.

- Transparent Reporting: Clearly document sources of heterogeneity and their potential impact on conclusions.

- Methodological Rigor: Use appropriate statistical models that account for heterogeneity and uncertainty.

By implementing these strategies, researchers can enhance the validity and utility of NMAs for informing drug development decisions and clinical practice guidelines.

Advanced Methods for Investigating and Explaining Heterogeneity in Drug Networks

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is network meta-regression and how does it differ from standard network meta-analysis? Network meta-regression (NMR) is an extension of network meta-analysis (NMA) that adds study-level covariates to the statistical model [18]. While standard NMA estimates the relative effects of multiple treatments, NMR investigates how these treatment effects change with study-level characteristics, often called effect modifiers [19]. This is particularly valuable for exploring heterogeneity (differences in treatment effects across studies) and inconsistency (disagreements between direct and indirect evidence) within a treatment network [18]. NMR allows researchers to explore interactions between treatments and study-level covariates, providing insights into why treatment effects might vary across different populations or settings [18].

2. When should I consider using network meta-regression in my analysis? You should consider NMR when your NMA shows substantial heterogeneity or inconsistency that might be explained by study-level characteristics [19]. This approach is particularly useful when you suspect that patient demographics (e.g., average age, disease severity), study methods (e.g., risk of bias, study duration), or treatment modalities might influence the relative treatment effects [8] [19]. NMR helps determine whether certain covariates modify treatment effects, which is crucial for making appropriate treatment recommendations for specific patient populations [18].

3. What are the key assumptions for valid network meta-regression? NMR relies on the same core assumptions as NMA but extends them to include covariates:

- Transitivity: The distribution of effect modifiers (covariates) should be similar across treatment comparisons [20] [8]. For example, studies comparing A vs. B should have similar covariate distributions to studies comparing A vs. C.

- Consistency (Coherence): The direct and indirect evidence for a treatment comparison should agree after accounting for the covariate effects [8] [21]. Statistical tests can examine whether disagreement remains after including covariates in the model.

- Similarity: Studies included in the network should be sufficiently similar in terms of populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes [20].

- Linear Relationship: NMR typically assumes a linear relationship between covariates and treatment effects, though this can be checked and addressed if violated [19].

4. What types of covariates can be analyzed using network meta-regression? NMR can analyze various study-level covariates, including:

- Clinical Diversity: Average patient age, baseline risk, disease severity, comorbidities [19]

- Methodological Diversity: Risk of bias, study duration, year of publication [19]

- Treatment Characteristics: Dose, administration route, treatment duration

- Contextual Factors: Geographic region, healthcare setting [8]

5. How does MetaInsight facilitate network meta-regression? MetaInsight is a free, open-source web application that implements NMR through a point-and-click interface, eliminating the need for statistical programming [18]. It offers:

- Interactive covariate exploration with visualizations showing distribution of covariate values across studies [18]

- Novel visualizations showing which studies contribute to which comparisons simultaneously [18]

- Support for different types of regression coefficients (shared, exchangeable, unrelated) [18]

- Correct handling of uncertainty in baseline risk analysis [18]

Table 1: Types of Regression Coefficients in Network Meta-Regression

| Coefficient Type | Description | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Shared | Assumes the same relationship between the covariate and each treatment | When you expect the covariate to affect all treatments similarly |

| Exchangeable | Allows different but related relationships for each treatment | When the covariate effect might vary by treatment but you want to borrow strength across treatments |

| Unrelated | Estimates completely separate relationships for each treatment | When you suspect fundamentally different covariate effects for different treatments |

Troubleshooting Common NMR Implementation Issues

Problem: High Heterogeneity Persists After Adding Covariates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Covariate Selection: The chosen covariates might not be the true effect modifiers. Consider conducting a systematic literature review to identify potential effect modifiers you may have overlooked [19].

- Non-linear Relationships: The relationship between the covariate and treatment effect might not be linear. Explore using fractional polynomials or restricted cubic splines to capture non-linear effects [19].

- Missing Important Covariates: Critical effect modifiers might not have been measured or reported in the primary studies. Acknowledge this limitation in your interpretation [8].

- Incorrect Functional Form: Continuous covariates might need transformation (e.g., log transformation) to properly model their relationship with treatment effects [19].

Problem: Computational Convergence Issues in NMR Models

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Simplify the Model: Start with a basic model with fewer parameters and gradually add complexity [19].

- Check Covariate Scaling: Rescale continuous covariates (e.g., mean-center) to improve numerical stability [19].

- Increase Iterations: Allow more iterations for the estimation algorithm to converge [19].

- Try Different Estimation Methods: Switch between estimation methods (e.g., REML vs. maximum likelihood) if available [19].

Problem: Inconsistency (Disagreement Between Direct and Indirect Evidence)

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Use Statistical Tests: Employ specific inconsistency tests (e.g., node-splitting) to identify where inconsistency occurs [8].

- Check for Effect Modifiers: Inconsistency often indicates unaccounted effect modifiers. Explore whether adding covariates resolves the inconsistency [8].

- Examine Network Structure: Some network configurations (e.g., large loops with limited direct evidence) are more prone to inconsistency [8].

Table 2: Common NMR Errors and Solutions

| Error | Possible Causes | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Model won't converge | Too many parameters, extreme covariate values, complex random effects structure | Simplify model, check for outliers, use different starting values, try alternative estimation methods |

| Implausible effect estimates | Model misspecification, data errors, insufficient data | Verify data quality, check model assumptions, conduct sensitivity analyses, consider alternative functional forms |

| Conflicting direct and indirect evidence | Violation of transitivity assumption, unmeasured effect modifiers | Test transitivity assumption, explore additional covariates, use inconsistency models if appropriate |

| High uncertainty in covariate effects | Limited sample size, insufficient variation in covariates, collinearity | Acknowledge limitation, consider Bayesian approaches with informative priors if justified, report results with appropriate caution |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Network Meta-Regression Using MetaInsight

Materials and Software Requirements:

- MetaInsight web application (https://apps.crsu.org.uk/MetaInsight) [18]

- Structured dataset with treatment effects and covariates

- Web browser with JavaScript enabled

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Preparation:

- Organize your NMA data with columns for study ID, treatment comparisons, effect sizes, variances, and covariates

- Ensure categorical covariates are properly coded

- Check for missing data in covariates

Model Specification:

- Select the regression coefficient type (shared, exchangeable, or unrelated) based on your assumptions about how covariates affect treatments [18]

- Choose appropriate link functions based on your outcome type (e.g., logit for binary outcomes)

- Specify random effects structure to account for between-study heterogeneity

Model Fitting and Diagnostics:

- Run the NMR model in MetaInsight

- Check convergence statistics

- Examine residual plots for patterns suggesting model misspecification

- Conduct sensitivity analyses with different prior distributions (if using Bayesian methods)

Interpretation and Visualization:

- Interpret covariate coefficients in the context of your outcome measure

- Use MetaInsight's novel visualizations to present which studies contribute to which comparisons [18]

- Create prediction plots showing how treatment effects vary across covariate values

Protocol 2: Assessing Transitivity Assumption in NMR

Background: The transitivity assumption requires that the distribution of effect modifiers is similar across treatment comparisons [8]. Violation of this assumption can lead to biased estimates.

Assessment Methodology:

Identify Potential Effect Modifiers:

- Conduct systematic literature review to identify patient or study characteristics that may modify treatment effects

- Consider clinical rationale for how covariates might influence treatment effects

Compare Covariate Distributions:

- Create summary tables comparing the distribution of covariates across different treatment comparisons

- Use statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA for continuous variables, chi-square for categorical) to assess differences

- Consider the clinical relevance of any differences, not just statistical significance

Evaluate Transitivity Violation Impact:

- Conduct sensitivity analyses excluding studies with extreme covariate values

- Fit separate models to subsets of studies with similar covariate profiles

- Use meta-regression to directly test whether treatment-by-covariate interactions explain observed differences

Figure 1: Network Meta-Regression Implementation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Network Meta-Regression Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MetaInsight Application | Point-and-click interface for performing NMR without programming [18] | Free web-based tool; supports various regression coefficient types and visualization |

| R packages (gemtc, bnma) | Statistical programming packages for advanced NMR models [18] | Required for complex models beyond MetaInsight's capabilities; steep learning curve |

| PRISMA-NMA Guidelines | Reporting standards for network meta-analyses and extensions [20] | Ensure comprehensive reporting of methods and results |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool | Assess methodological quality of included studies [8] | Important covariate for exploring heterogeneity due to study quality |

| GRADE Framework for NMA | Assess confidence in evidence from network meta-analyses [22] | Adapt for assessing confidence in NMR findings |

| ColorBrewer Palettes | Color selection for effective data visualizations [23] | Ensure accessibility for colorblind readers; use appropriate palette types |

| Pyrintegrin | Pyrintegrin, MF:C23H25N5O3S, MW:451.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PZ-2891 | PZ-2891, CAS:2170608-82-7, MF:C20H23N5O, MW:349.438 | Chemical Reagent |

Figure 2: Conceptual Framework for Addressing Heterogeneity Through NMR

Advanced Implementation Considerations

Handling Different Types of Covariates in NMR:

- Continuous Covariates: Assess linearity assumption; consider transformations or flexible modeling approaches if non-linear relationships are suspected [19].

- Categorical Covariates: Use appropriate reference categories; be cautious with sparse categories which can lead to estimation problems.

- Baseline Risk: Special consideration is needed as it represents the outcome risk in the control group and requires proper accounting of uncertainty [18].

Statistical Implementation Details:

The statistical model for random-effects NMR can be represented as [19]:

[ \hat\thetai = \beta0 + \beta1 x{i1} + \beta2 x{i2} + \cdots + \betap x{ip} + ui + \varepsiloni ]

Where:

- (\hat\theta_i) is the estimated effect size in study (i)

- (\beta_0) is the intercept

- (\beta1, \beta2, \ldots, \betap) are regression coefficients for covariates (x{i1}, x{i2}, \ldots, x{ip})

- (u_i) is the random effect for study (i), assumed to follow (N(0, \tau^2))

- (\varepsiloni) is the sampling error, assumed to follow (N(0, \sigmai^2))

The model simultaneously estimates the regression coefficients ((\beta) parameters) and the between-study heterogeneity ((\tau^2)).

Best Practices for Reporting NMR Results:

- Transparent Methods: Clearly describe how covariates were selected, including both clinical rationale and statistical considerations [8].

- Model Specification: Report the type of regression coefficients used (shared, exchangeable, or unrelated) and the justification for this choice [18].

- Assumption Checks: Document how transitivity and consistency assumptions were assessed, including any statistical tests performed [8].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Report confidence/credible intervals for all covariate effects and acknowledge limitations in precision when sample sizes are small [19].

- Visualization: Use MetaInsight's visualization capabilities or create custom plots to show how treatment effects vary with covariates [18].

- Clinical Interpretation: Translate statistical findings into clinically meaningful information that can guide treatment decisions for specific patient populations.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core difference between a standard Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) and a Component NMA (CNMA)?

In a standard NMA, each unique combination of intervention components is treated as a separate, distinct node in the network [24] [25]. For example, the combinations "Exercise + Nutrition" and "Exercise + Psychosocial" would be two different nodes. The analysis estimates the effect of each entire combination.

In contrast, a CNMA model decomposes these complex interventions into their constituent parts [24] [25]. It estimates the effect of each individual component (e.g., Exercise, Nutrition, Psychosocial). The effect of a complex intervention is then modeled as a function of its components, either simply as the sum of its parts (additive model) or including interaction terms between components (interaction model) [25].

2. When should I consider using a CNMA model?

A CNMA is particularly useful when [24] [25]:

- Your research question aims to identify which specific components of an intervention are driving its effectiveness or harm.

- You want to predict the effect of a novel combination of components that has not been directly tested in a trial.

- The evidence network is sparse, with many unique combinations but few trials connecting them, leading to imprecise estimates in a standard NMA.

3. My CNMA model failed to run or produced errors. What are common culprits?

A frequent issue is that the evidence structure does not support the model you are trying to fit [24]. Specifically:

- Non-Identifiable Components: If two or more components always appear together in every trial (perfectly co-linear), the additive CNMA model cannot distinguish their individual effects [24].

- Insufficient Data for Interactions: An interaction CNMA model requires a rich evidence base. If there are not enough studies testing the relevant combinations, the model may fail to converge or produce estimates with extreme uncertainty [24] [25].

4. How can I visualize a network of components when a standard network diagram becomes too cluttered?

For complex component networks, novel visualizations are recommended over standard NMA network diagrams [24]:

- CNMA-UpSet Plot: Ideal for large networks, it effectively presents the arm-level data and shows which combinations of components have been studied.

- CNMA-Circle Plot: Visualizes the combinations of components that differ between trial arms and can be flexible in presenting additional information like the number of events.

- CNMA Heat Map: Can be used to inform decisions about which pairwise component interactions to consider including in the model.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Determining the Unit of Analysis for Nodes

Background: A foundational step in planning a CNMA is deciding how to define the nodes in your evidence network. An incorrect strategy can lead to a model that is uninterpretable or does not answer the relevant clinical question.

Solution: Your node-making strategy should be driven by the review's specific research question. The following table outlines common strategies.

Table: Node-Making Strategies for Component Network Meta-Analysis

| Strategy | Description | Best Used When | Example from Prehabilitation Research [25] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lumping | Grouping different complex interventions into a single node. | The question is whether a general class of intervention works compared to a control. | All prehabilitation interventions (regardless of components) vs. Usual Care. |

| Splitting (Standard NMA) | Treating every unique combination of components as a distinct node. | The question requires comparing specific, multi-component packages. | "Exercise + Nutrition" and "Exercise + Psychosocial" are separate nodes. |

| Component NMA | Defining nodes based on the presence or absence of individual components. | The goal is to disentangle the effect of individual components within complex interventions. | Nodes are the components themselves: "Exercise", "Nutrition", "Psychosocial". |

Problem: Selecting an Appropriate CNMA Model

Background: After defining components, you must choose a statistical model that correctly represents how these components combine to produce an effect. An incorrect model can lead to biased conclusions.

Solution: Follow this step-by-step protocol to select and check your model.

Experimental Protocol: Model Selection for CNMA

- Specify Components: Clearly list all intervention components from the included studies. In the prehabilitation example, these were Exercise (EXE), Nutrition (NUT), Cognitive (COG), and Psychosocial (PSY) [25].

- Fit the Additive CNMA Model: Start with the simplest model, which assumes the effect of a combination is the sum of the effects of its individual components (e.g., the effect of EXE+NUT = effect of EXE + effect of NUT) [24] [25].

- Check for Model Inadequacy: Assess if the additive model is sufficient. Significant disagreement between the CNMA model estimates and the direct evidence from standard NMA may suggest that important component interactions (synergy or antagonism) are present [25].

- Fit an Interaction CNMA Model: If the additive model is inadequate, include specific interaction terms. This model is a compromise between the additive model and the standard NMA [25].

- Clinical Input: Engage clinical experts to select biologically plausible interactions to test (e.g., an interaction between Exercise and Nutrition).

- Statistical Considerations: Only include interaction terms for which the evidence network provides sufficient data.

- Compare Models: Use statistical fit indices (e.g., Deviance Information Criterion) to compare the additive and interaction models, balancing fit and complexity.

Problem: Visualizing the Component Network and Data Structure

Background: A standard network graph can become unreadable with many components. You need a clear way to communicate which component combinations have been tested.

Solution: Creating a CNMA-Circle Plot The following workflow and diagram illustrate the logic behind creating a CNMA-circle plot, which is effective for this purpose [24].

Diagram: Workflow for Generating a CNMA-Circle Plot

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents for Component Network Meta-Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Tools & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary environment for statistical computing and modeling. | Base R environment. |

netmeta Package |

Implements frequentist network meta-analysis, a foundation for some CNMA models. | Key package for NMA and CNMA in frequentist framework [24]. |

tidygraph & ggraph |

A tidy API for graph (network) manipulation and visualization in R. | Used to create custom network visualizations [26]. |

| CNMA-UpSet Plot | A visualization method to display arm-level data and component combinations in large networks. | An alternative to complex network diagrams [24]. |

| Component Coding Matrix | A structured data frame (e.g., in CSV format) indicating the presence (1) or absence (0) of each component in every intervention arm. | The essential data structure for fitting CNMA models. |

| Factorial RCT Design | The ideal primary study design for cleanly estimating individual and interactive component effects. | Rarely used in practice due to resource constraints, which is why CNMA is needed [25]. |

| Quininib | Quininib|CysLT1 Antagonist|For Research | Quininib is a CysLT1 receptor antagonist for cancer and ocular disease research. This product is for research use only and not for human use. |

| Rabeximod | Rabeximod, CAS:872178-65-9, MF:C22H24ClN5O, MW:409.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are class-effect models in Network Meta-Analysis and when should I use them? Class-effect models are hierarchical NMA models used when treatments can be grouped into classes based on shared mechanisms of action, chemical structure, or other common characteristics. You should consider them when making recommendations at the class level, addressing challenges with sparse data for individual treatments, or working with disconnected networks. These models can improve precision by borrowing strength from treatments within the same class [27] [28].

2. My network is disconnected, with no direct or indirect paths between some treatments. Can class-effect models help? Yes, implementing a class-effect model is a recognized method to connect disconnected networks. When disconnected treatments share a similar mechanism of action with connected treatments, assuming a class effect can provide the necessary link, allowing for the estimation of relative effects that would otherwise be impossible in a standard NMA [29].

3. What is the difference between common and exchangeable class-level effects? In a common class effect, all treatments within the same class are assumed to have identical class-level components—that is, there is no within-class variation. In contrast, an exchangeable class effect (or random class effect) assumes that the class-level components for treatments within a class are similar but not identical, and are drawn from a common distribution, allowing for within-class heterogeneity [27] [28].

4. How do I check if the assumption of a class effect is valid in my analysis? It is crucial to assess the class effect assumption as part of the model selection process. This involves testing for consistency, checking heterogeneity, and evaluating model fit. A structured model selection strategy should be employed to compare models with and without class effects, using statistical measures to identify the most suitable model for your data [27].

5. I have both randomized trials and non-randomized studies. Can I use class-effect models? Yes, hierarchical NMA models can be extended to synthesize evidence from both randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies. These models can account for differences in study design, for instance by including random effects for study design or bias adjustment terms for non-randomized evidence, while also incorporating treatment class effects [30].

6. What software can I use to implement a class-effect NMA?